- Tachykinin receptor 1

-

The tachykinin receptor 1 (TACR1) also known as neurokinin 1 receptor (NK1R) or substance P receptor (SPR) is a G protein coupled receptor found in the central nervous system and peripheral nervous system. The endogenous ligand for this receptor is Substance P, although it has some affinity for other tachykinins. The protein is the product of the TACR1 gene.[1]

Contents

Properties

Tachykinins are a family of neuropeptides that share the same hydrophobic C-terminal region with the amino acid sequence Phe-X-Gly-Leu-Met-NH2, where X represents a hydrophobic residue that is either an aromatic or a beta-branched aliphatic. The N-terminal region varies between different tachykinins.[2][3][4] The term tachykinin originates in the rapid onset of action caused by the peptides in smooth muscles.[4] SP is the most researched and potent member of the tachykinin family. It is an undecapeptide with the amino acid sequence Arg-Pro-Lys-Pro-Gln-Gln-Phe-Phe-Gly-Leu-Met-NH2.[2] SP binds to all three of the tachykinin receptors, but it binds most strongly to the NK1 receptor.[3]

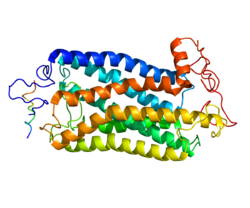

Tachykinin NK1 receptor[5] consists of 407 amino acid residues, and it has a molecular weight of 58.000.[2][6] NK1 receptor, as well as the other tachykinin receptors, is made of seven hydrophobic transmembrane (TM) domains with three extracellular and three intracellular loops, an amino-terminus and a cytoplasmic carboxy-terminus. The loops have functional sites, including two cysteines amino acids for a disulfide bridge, Asp-Arg-Tyr, which is responsible for association with arrestin and, Lys/Arg-Lys/Arg-X-X-Lys/Arg, which interacts with G-proteins.[5][6]

Distribution and function

The NK1 receptor can be found in both the central and peripheral nervous system. It is present in neurons, brainstem, vascular endothelial cells, muscle, gastrointestinal tracts, genitourinary tract, pulmonary tissue, thyroid gland and different types of immune cells.[5][7][4][6] The binding of SP to the NK1 receptor has been associated with the transmission of stress signals and pain, the contraction of smooth muscles and inflammation.[8] NK1 receptor antagonists have also been studied in migraine, emesis and psychiatric disorders. In fact, aprepitant has been proved effective in a number of pathophysiological models of anxiety and depression.[9] Other diseases in which the NK1 receptor system is involved include asthma, rheumatoid arthritis and gastrointestinal disorders.[10]

Mechanism

SP is synthesized by neurons and transported to synaptic vesicles; the release of SP is accomplished through the depolarizing action of calcium-dependent mechanisms.[2] When NK1 receptors are stimulated, they can generate various second messengers, which can trigger a wide range of effector mechanisms that regulate cellular excitability and function. One of those three well-defined, independent second messenger systems is stimulation, via phospholipase C, of phosphatidyl inositol, turnover leading to Ca mobilization from both intra- and extracellular sources. Second is the arachidonic acid mobilization via phospholipase A2 and third is the cAMP accumulation via stimulation of adenylate cyclase.[11] It has also been reported that SP elicits interleukin-1 (IL-1) production in macrophages, is known to sensitize neutrophils and enhance dopamine release in the substantia nigra region in cat brain. From spinal neurons, SP is known to evoke release of neurotransmitters like acetylcholine, histamine and GABA. It is also known to secrete catecholamines and play a role in the regulation of blood pressure and hypertension. Likewise, SP is known to bind to N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors by eliciting excitation with calcium ion influx, which further releases nitric oxide. Studies in frogs have shown that SP elicits the release of prostaglandin E2 and prostacyclin by the arachidonic acid pathway, which leads to an increase in corticosteroid output.[4]

In combination therapy, NK1 receptor antagonists appear to offer better control of delayed emesis and post-operative emesis than drug therapy without NK1 receptor antagonists. NK1 receptor antagonists block responses to a broader range of emetic stimuli than the established 5-HT3 antagonist treatments.[10] It has been reported that centrally-acting NK1 receptors antagonists, such as CP-99994, inhibit emesis induced by apomorphine and loperimidine, which are two compounds that act through central mechanisms.[7]

Clinical significance

This receptor is considered an attractive drug target, particularly with regards to potential analgesics and anti-depressants.[12][13] It was identified as a candidate in the etiology of bipolar disorder by a 2008 study.[14] Furthermore TACR1 antagonists have shown promise for the treatment in alcoholism.[15] Finally TACR1 antagonists may also have a role as novel antiemetics.[16]

Selective ligands

Many selective ligands for NK1 are now available, several of which have gone into clinical use as antiemetics.

Agonists

- GR-73632 - potent and selective agonist, EC50 2nM, 5-amino acid polypeptide chain. CAS# 133156-06-6

Antagonists

- Aprepitant

- Casopitant

- Ezlopitant

- Fosaprepitant

- Lanepitant

- Maropitant

- Vestipitant

- L-733,060

- L-741,671

- L-742,694

- RP-67580 - potent and selective antagonist, Ki 2.9nM, (3aR,7aR)-Octahydro-2-[1-imino-2-(2-methoxyphenyl)ethyl ]-7,7-diphenyl-4H-isoindol, CAS# 135911-02-3

- RPR-100,893

- CP-96345

- CP-99994

- GR-205,171

- TAK-637

- T-2328

See also

- NK1 receptor antagonist

- Tachykinin receptor

- Discovery and development of neurokinin 1 receptor antagonists

References

- ^ Takeda Y, Chou KB, Takeda J, Sachais BS, Krause JE (1991). "Molecular cloning, structural characterization and functional expression of the human substance P receptor". Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 179 (3): 1232–1240. doi:10.1016/0006-291X(91)91704-G. PMID 1718267.

- ^ a b c d Ho, W. Z.; Douglas, S. D. (December 2004). "Substance P and neurokinin-1 receptor modulation of HIV". Journal of Neuroimmunology 157 (1–2): 48–55. doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.08.022. PMID 15579279. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6T03-4DP8JT6-2&_user=5915660&_rdoc=1&_fmt=&_orig=search&_sort=d&view=c&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=5915660&md5=3e140fa2944d54a39f08db8451ff9005=Citation

- ^ a b Page, N. M. (August 2005). "New challenges in the study of the mammalian Tachykinins". Peptides 26 (8): 1356–1368. doi:10.1016/j.peptides.2005.03.030. PMID 16042976. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6T0M-4G0DDS8-4&_user=5915660&_rdoc=1&_fmt=&_orig=search&_sort=d&view=c&_acct=C000068853&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=5915660&md5=9523f37237e3a7147329fb4f28ffacec=Citation

- ^ a b c d Datar, P.; Srivastava, S.; Coutinho, E.; Govil, G. (2004). "Substance P: Structure, Function, and Therapeutics". Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry 4 (1): 75–103. doi:10.2174/1568026043451636. PMID 14754378. http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail?vid=3&hid=14&sid=cbd0171a-72ef-47c3-bae2-063f39b1af3a%40sessionmgr2&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#db=aph&AN=12076762=Citation

- ^ a b c Satake, H.; Kawada, T. (August 2006). "Overview of the primary structure, tissue-distribution, and functions of tachykinins and their receptors". Current Drug Targets 7 (8): 963–974. doi:10.2174/138945006778019273. http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail?vid=3&hid=8&sid=c900290b-e38a-4b8e-9dac-9f513104331b%40sessionmgr3&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#db=aph&AN=21848311=Citation

- ^ a b c Almeida, T. A.; Rojo, J.; Nieto, P. M.; Hernandez, FM; Martin, J. D.; Candenas, M. L.; Candenas, ML (August 2004). "Tachykinins and Tachykinins Receptors: Structure and Activity Relationships". Current Medicinal Chemistry 11 (15): 2045–81. PMID 15279567. http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail?vid=3&hid=4&sid=4b46c517-3764-45fc-9dbd-1cb9d1cec680%40sessionmgr3&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#db=aph&AN=13996759=Citation

- ^ a b Saria, A. (June 1999). "The Tachykinin NK1 receptor in the brain: pharmacology and putative functions". European Journal of Pharmacology 375 (1–3): 51–60. doi:10.1016/S0014-2999(99)00259-9. PMID 10443564. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6T1J-3WXP063-5&_user=5915660&_rdoc=1&_fmt=&_orig=search&_sort=d&view=c&_acct=C000068853&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=5915660&md5=d6f447ad6a3e03bd50e933e605128c93=Citation

- ^ Seto, S.; Tanioka, A.; Ikeda, M.; Izawa, S. (March 2005). "Design and synthesis of novel 9-substituted-7-aryl-3,4,5,6-tetrahydro-2H-pyrido(4,3-b)- and (2,3-b)-1,5-oxazocin-6-ones as NK1 antagonists". Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry Letters 15 (5): 1479–1484. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.12.091. PMID 15713411. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6TF9-4FC3RRY-2&_user=5915660&_rdoc=1&_fmt=&_orig=search&_sort=d&view=c&_acct=C000068853&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=5915660&md5=50433f05a52a1184a13e6ecf3ecb9ff2=Citation

- ^ Quartara, L.; Altamura, M. (August 2006). "Tachykinin receptors antagonists: From research to clinic". Current Drug Targets 7 (8): 975–992. doi:10.2174/138945006778019381. PMID 16918326. http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail?vid=3&hid=3&sid=1209dba9-203c-4bb0-990a-5cd3c9c841e7%40sessionmgr9&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#db=aph&AN=21848310=Citation

- ^ a b Humphrey, J. M. (2003). "Medicinal Chemistry of Selective Neurokinin-1 Antagonists". Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry 3 (12): 1423–1435. doi:10.2174/1568026033451925. PMID 12871173. http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail?vid=4&hid=15&sid=c04bf2f1-4f7a-45ce-a30b-092df0686266%40sessionmgr9&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#db=aph&AN=11436699=Citation

- ^ Quartara, L.; Maggi, C. A. (December 1997). "The tachykinin NK1 receptor. Part I: Ligands and mechanisms of cellular activation". Neuropeptides 31 (6): 537–563. doi:10.1016/S0143-4179(97)90001-9. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6WNR-4D2PDGX-99&_user=6149268&_coverDate=12%2F31%2F1997&_rdoc=1&_fmt=&_orig=search&_sort=d&view=c&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=6149268&md5=69ab83979bd30d4d78e036b75ec0f871=Citation

- ^ Humphrey JM (2003). "Medicinal chemistry of selective neurokinin-1 antagonists". Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry 3 (12): 1423–1435. doi:10.2174/1568026033451925. PMID 12871173.

- ^ Yu YJ, Arttamangkul S, Evans CJ, Williams JT, von Zastrow M (January 2009). "Neurokinin 1 receptors regulate morphine-induced endocytosis and desensitization of mu-opioid receptors in CNS neurons". Journal of Neuroscience 29 (1): 222–233. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4315-08.2009. PMC 2775560. PMID 19129399. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2775560.

- ^ Perlis RH, Purcell S, Fagerness J, Kirby A, Petryshen TL, Fan J, Sklar P (January 2008). "Family-based association study of lithium-related and other candidate genes in bipolar disorder". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 65 (1): 53–61. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.15. PMID 18180429.

- ^ George DT, Gilman J, Hersh J, Thorsell A, Herion D, Geyer C, Peng X, Kielbasa W, Rawlings R, Brandt JE, Gehlert DR, Tauscher JT, Hunt SP, Hommer D, Heilig M (March 2008). "Neurokinin 1 receptor antagonism as a possible therapy for alcoholism". Science 319 (5869): 1536–1539. doi:10.1126/science.1153813. PMID 18276852.

- ^ Jordan K (2006). "Neurokinin-1-receptor antagonists: a new approach in antiemetic therapy". Onkologie 29 (1–2): 39–43. doi:10.1159/000089800. PMID 16514255.

Further reading

- Burcher E (1989). "The study of tachykinin receptors". Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 16 (6): 539–543. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1681.1989.tb01602.x. PMID 2548782.

- Kowall NW, Quigley BJ, Krause JE et al. (1993). "Substance P and substance P receptor histochemistry in human neurodegenerative diseases". Regul. Pept. 46 (1–2): 174–185. doi:10.1016/0167-0115(93)90028-7. PMID 7692486.

- Patacchini R, Maggi CA (2002). "Peripheral tachykinin receptors as targets for new drugs". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 429 (1–3): 13–21. doi:10.1016/S0014-2999(01)01301-2. PMID 11698023.

- Saito R, Takano Y, Kamiya HO (2003). "Roles of substance P and NK(1) receptor in the brainstem in the development of emesis". J. Pharmacol. Sci. 91 (2): 87–94. doi:10.1254/jphs.91.87. PMID 12686752.

- Fong TM, Yu H, Huang RR, Strader CD (1992). "The extracellular domain of the neurokinin-1 receptor is required for high-affinity binding of peptides". Biochemistry 31 (47): 11806–11811. doi:10.1021/bi00162a019. PMID 1280161.

- Fong TM, Huang RR, Strader CD (1993). "Localization of agonist and antagonist binding domains of the human neurokinin-1 receptor". J. Biol. Chem. 267 (36): 25664–7. PMID 1281469.

- Fong TM, Anderson SA, Yu H et al. (1992). "Differential activation of intracellular effector by two isoforms of human neurokinin-1 receptor". Mol. Pharmacol. 41 (1): 24–30. PMID 1310144.

- Takahashi K, Tanaka A, Hara M, Nakanishi S (1992). "The primary structure and gene organization of human substance P and neuromedin K receptors". Eur. J. Biochem. 204 (3): 1025–1033. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb16724.x. PMID 1312928.

- Walsh DA, Mapp PI, Wharton J et al. (1992). "Localisation and characterisation of substance P binding to human synovial tissue in rheumatoid arthritis". Ann. Rheum. Dis. 51 (3): 313–317. doi:10.1136/ard.51.3.313. PMC 1004650. PMID 1374227. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1004650.

- Gerard NP, Garraway LA, Eddy RL et al. (1991). "Human substance P receptor (NK-1): organization of the gene, chromosome localization, and functional expression of cDNA clones". Biochemistry 30 (44): 10640–10646. doi:10.1021/bi00108a006. PMID 1657150.

- Hopkins B, Powell SJ, Danks P et al. (1991). "Isolation and characterisation of the human lung NK-1 receptor cDNA". Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 180 (2): 1110–1117. doi:10.1016/S0006-291X(05)81181-7. PMID 1659396.

- Takeda Y, Chou KB, Takeda J et al. (1991). "Molecular cloning, structural characterization and functional expression of the human substance P receptor". Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 179 (3): 1232–1240. doi:10.1016/0006-291X(91)91704-G. PMID 1718267.

- Giuliani S, Barbanti G, Turini D et al. (1992). "NK2 tachykinin receptors and contraction of circular muscle of the human colon: characterization of the NK2 receptor subtype". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 203 (3): 365–370. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(91)90892-T. PMID 1723045.

- Ichinose H, Katoh S, Sueoka T et al. (1991). "Cloning and sequencing of cDNA encoding human sepiapterin reductase--an enzyme involved in tetrahydrobiopterin biosynthesis". Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 179 (1): 183–189. doi:10.1016/0006-291X(91)91352-D. PMID 1883349.

- Thöny B, Heizmann CW, Mattei MG (1995). "Human GTP-cyclohydrolase I gene and sepiapterin reductase gene map to region 14q21-q22 and 2p14-p12, respectively, by in situ hybridization". Genomics 26 (1): 168–170. doi:10.1016/0888-7543(95)80101-Q. PMID 7782081.

- Fong TM, Cascieri MA, Yu H et al. (1993). "Amino-aromatic interaction between histidine 197 of the neurokinin-1 receptor and CP 96345". Nature 362 (6418): 350–353. doi:10.1038/362350a0. PMID 8384323.

- Derocq JM, Ségui M, Blazy C et al. (1997). "Effect of substance P on cytokine production by human astrocytic cells and blood mononuclear cells: characterization of novel tachykinin receptor antagonists". FEBS Lett. 399 (3): 321–325. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(96)01346-4. PMID 8985172.

- De Felipe C, Herrero JF, O'Brien JA et al. (1998). "Altered nociception, analgesia and aggression in mice lacking the receptor for substance P". Nature 392 (6674): 394–397. doi:10.1038/32904. PMID 9537323.

External links

- "Tachykinin Receptors: NK1". IUPHAR Database of Receptors and Ion Channels. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. http://www.iuphar-db.org/GPCR/ReceptorDisplayForward?receptorID=3029.

- MeSH Receptors,+Neurokinin-1

Cell surface receptor: G protein-coupled receptors Class A:

Rhodopsin likeOtherMetabolites and

signaling moleculesOtherBile acid · Cannabinoid (CB1, CB2, GPR (18, 55, 119)) · EBI2 · Estrogen · Free fatty acid (1, 2, 3, 4) · Lactate · Lysophosphatidic acid (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6) · Lysophospholipid (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8) · Niacin (1, 2) · Oxoglutarate · PAF · Sphingosine-1-phosphate (1, 2, 3, 4, 5) · SuccinatePeptideOtherAnaphylatoxin (C3a, C5a) · Angiotensin (1, 2) · Apelin · Bombesin (BRS3, GRPR, NMBR) · Bradykinin (B1, B2) · Chemokine · Cholecystokinin (A, B) · Endothelin (A, B) · Formyl peptide (1, 2, 3) · FSH · Galanin (1, 2, 3) · GHB receptor · Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (1, 2) · Ghrelin · Kisspeptin · Luteinizing hormone/choriogonadotropin · MAS (1, 1L, D, E, F, G, X1, X2, X3, X4) · Melanocortin (1, 2, 3, 4, 5) · MCHR (1, 2) · Motilin · Opioid (Delta, Kappa, Mu, Nociceptin & Zeta, but not Sigma) · Orexin (1, 2) · Oxytocin · Prokineticin (1, 2) · Prolactin-releasing peptide · Relaxin (1, 2, 3, 4) · Somatostatin (1, 2, 3, 4, 5) · Tachykinin (1, 2, 3) · Thyrotropin · Thyrotropin-releasing hormone · Urotensin-II · Vasopressin (1A, 1B, 2)MiscellaneousGPR (1, 3, 4, 6, 12, 15, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 25, 26, 27, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 37, 39, 42, 44, 45, 50, 52, 55, 61, 62, 63, 65, 68, 75, 77, 78, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 87, 88, 92, 101, 103, 109A, 109B, 119, 120, 132, 135, 137B, 139, 141, 142, 146, 148, 149, 150, 151, 152, 153, 160, 161, 162, 171, 173, 174, 176, 177, 182, 183)OtherClass B: Secretin like OtherBrain-specific angiogenesis inhibitor (1, 2, 3) · Cadherin (1, 2, 3) · Calcitonin · CALCRL · CD97 · Corticotropin-releasing hormone (1, 2) · EMR (1, 2, 3) · Glucagon (GR, GIPR, GLP1R, GLP2R) · Growth hormone releasing hormone · PACAPR1 · GPR · Latrophilin (1, 2, 3, ELTD1) · Methuselah-like proteins · Parathyroid hormone (1, 2) · Secretin · Vasoactive intestinal peptide (1, 2)Class C: Metabotropic

glutamate / pheromoneOtherClass F:

Frizzled / SmoothenedFrizzledSmoothenedNeuropeptide receptors G protein-coupled receptor OtherOther neuropeptide receptorsAngiotensin · Bradykinin (B1, B2) / Tachykinin (TACR1) · Calcitonin gene-related peptide · Galanin · GPCR neuropeptide (B/W, FF, S, Y) · NeurotensinType I cytokine receptor Enzyme-linked receptor Other Neuropeptidergics Cholecystokinin Agonists: Cholecystokinin • CCK-4

Antagonists: Asperlicin • Proglumide • Lorglumide • Devazepide • DexloxiglumideCRH Agonists: Corticotropin releasing hormoneGalanin Agonists: Galanin • Galanin-like peptide • Galmic • GalnonAgonists: Galanin • Galanin-like peptide • Galmic • GalnonAgonists: Galanin • Galmic • GalnonGhrelin MCH Agonists: Melanin concentrating hormone

Antagonists: ATC-0175 • GW-803,430 • NGD-4715 • SNAP-7941 • SNAP-94847Agonists: Melanin concentrating hormoneMelanocortin Agonists: alpha-MSH • Afamelanotide • Bremelanotide • Melanotan II

Antagonists: Agouti signalling peptideAgonists: alpha-MSH • Bremelanotide • Melanotan IIAgonists: alpha-MSH • Melanotan IINeuropeptide S Agonists: Neuropeptide S

Antagonists: SHA-68Neuropeptide Y Neurotensin Opioid see Template:OpioidsOrexin Oxytocin Agonists: Carbetocin • Demoxytocin • Oxytocin • WAY-267,464

Antagonists: Atosiban • Epelsiban • L-371,257 • L-368,899Tachykinin NK1Agonists: Substance P

Antagonists: Aprepitant • Befetupitant • Casopitant • CI-1021 • CP-96,345 • CP-99,994 • CP-122,721 • Dapitant • Ezlopitant • FK-888 • Fosaprepitant • GR-203,040 • GW-597,599 • HSP-117 • L-733,060 • L-741,671 • L-743,310 • L-758,298 • Lanepitant • LY-306,740 • Maropitant • Netupitant • NKP-608 • Nolpitantium • Orvepitant • RP-67,580 • SDZ NKT 343 • Vestipitant • VofopitantVasopressin Agonists: Desmopressin • Felypressin • Ornipressin • Terlipressin • Vasopressin

Antagonists: Conivaptan • Demeclocycline • RelcovaptanAgonists: Felypressin • Ornipressin • Terlipressin • Vasopressin

Antagonists: Demeclocycline • NelivaptanAgonists: Desmopressin • Ornipressin • Vasopressin

Antagonists: Conivaptan • Demeclocycline • Lixivaptan • Mozavaptan • Satavaptan • TolvaptanAnxiety disorder: Obsessive–compulsive disorder (F42, 300.3) History Yale–Brown Obsessive Compulsive ScaleBiology NeuroanatomyReceptorsSymptoms Obsessions (associative, diagnostic, injurious, scrupulous, pathogenic, sexual) · Compulsions (impulses, rituals, tics) · Thought suppression (avoidance) · Hoarding (animals, books, possessions)Treatment Mu opioidergicsNMDA glutamatergicsNK-1 tachykininergicsOtherBehavioralOrganizations Notable people Edna B. Foa · Stanley Rachman · Adam S. Radomsky · Jeffrey M. Schwartz · Susan Swedo · Jeff Bell · Emily ColasPopular culture LiteratureFictionalNonfictionEverything in Its Place · Just CheckingMediaRelated Obsessive–compulsive personality disorder · Obsessional jealousy · Purely Obsessional OCD · Social anxiety disorder · Tourette syndromeCategories:- Human proteins

- G protein coupled receptors

- Molecular neuroscience

- Biology of bipolar disorder

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.