- Orbitofrontal cortex

-

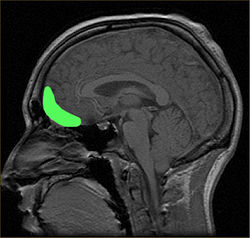

Brain: Orbitofrontal cortex Approximate location of the OFC shown on a sagittal MRI

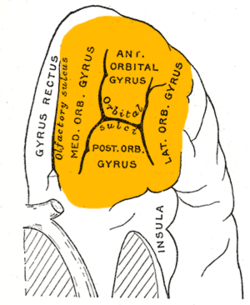

Orbital surface of left frontal lobe. Latin Cortex orbitofrontalis Gray's subject #189 822 NeuroNames hier-73 The orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) is a prefrontal cortex region in the frontal lobes in the brain which is involved in the cognitive processing of decision-making. It consists in non-human primates of the association cortex areas brodmann area 11, 12 and 13; in humans it consists of brodmann area 10, 11 and 47[1] Because of its functions in emotion and reward, the OFC is considered by some to be a part of the limbic system.

The OFC anatomically is defined as the part of the prefrontal cortex that receives projections from the magnocellular, medial nucleus of the mediodorsal thalamus.[2] It gets its name from its position immediately above the orbits in which the eyes are located. Considerable individual variability has been found in the OFC of both humans and non-human primates. A related area is found in rodents.[3]

Contents

Functions of the human orbitofrontal cortex

The human OFC is among the least-understood regions of the human brain; but it has been proposed that the OFC is involved in sensory integration, in representing the affective value of reinforcers, and in decision-making and expectation.[1] In particular, the human OFC is thought to regulate planning behavior associated with sensitivity to reward and punishment.[4] This is supported by research in humans, non-human primates, and rodents. Human research has focused on neuroimaging research in healthy participants and neuropsychology research in patients with damage to discrete parts of the OFC. Research at the University of Leipzig shows that the human OFC is activated during intuitive coherence judgements.[5]

Neuroimaging research in healthy participants

Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to image the human OFC is a challenge, because this brain region is in proximity to the air-filled sinuses. This means that signal dropout, geometric distortion and susceptibility artifacts are common when using EPI at higher magnetic field strengths. Extra care is therefore recommended for obtaining a good signal from the orbitofrontal cortex, and a number of strategies have been devised, such as automatic shimming at high static magnetic field strengths[6].

The published neuroimaging studies have found that the reward value, the expected reward value, and even the subjective pleasantness of foods and other reinforcers are represented in the OFC. A large meta-analysis of the existing neuroimaging evidence demonstrated that activity in medial parts of the OFC is related to the monitoring, learning, and memory of the reward value of reinforcers, whereas activity in lateral OFC is related to the evaluation of punishers, which may lead to a change in ongoing behaviour [7]. Similarly, a posterior-anterior distinction was found with more complex or abstract reinforcers (such as monetary gain and loss) being represented more anteriorly in the orbitofrontal cortex than less-complex reinforcers such as taste. It has even been proposed that the human OFC has a role in mediating subjective hedonic experience [1].

The orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) represents the main neocortical target of primary olfactory cortex. In non-human primates, the olfactory neocortex is situated along the basal surface of the caudal frontal lobes, encompassing agranular and dysgranular OFC medially and agranular insula laterally, where this latter structure wraps onto the posterior orbital surface. Direct afferent inputs arrive from most primary olfactory areas, including piriform cortex, amygdala, and entorhinal cortex, in the absence of an obligatory thalamic relay. [8].

Neuropsychology research in patients

Visual discrimination test

This has two components. In the first component, "reversal learning", participants are presented with one of two pictures, A and B. They learn that they will be rewarded if they press a button when picture A is displayed, but punished if they press the button when picture B is displayed. Once this rule has been established, the rule swaps. In other words, now it is correct to press the button for picture B, not picture A. Most healthy participants pick up on this rule reversal almost immediately, but patients with OFC damage continue to respond to the original pattern of reinforcement, although they are now being punished for persevering with it. Rolls et al.[9] noted that this pattern of behaviour is particularly unusual given that the patients reported that they understood the rule.

The second component of the test is "extinction". Again, participants learn to press the button for picture A but not picture B. However this time, instead of the rules reversing, the rule changes altogether. Now the participant will be punished for pressing the button in response to either picture. The correct response is not to press the button at all, but people with OFC dysfunction find it difficult to resist the temptation to press the button despite being punished for it.

Iowa gambling task

This simulation of real life decision-making is widely used in cognition and emotion research.[4] Participants are presented with four virtual decks of cards on a computer screen. They are told that each time they choose a card they will win some game money. Every so often, however, when they choose a card they will win lose some money. They are told that the aim of the game is to win as much money as possible. The task is meant to be opaque, i.e., participants are not meant to consciously work out the rule, and they are supposed to choose cards based on their "gut reaction." Two of the decks are "bad decks," which means that, over a long enough time, they will make a net loss; the other two decks are "good decks" and will make a net gain over time. Most healthy participants sample cards from each deck, and after about 40 or 50 selections are fairly good at sticking to the good decks. Patients with OFC dysfunction, however, continue to perseverate with the bad decks, sometimes even though they know that they are losing money overall. Concurrent measurement of galvanic skin response shows that healthy participants show a "stress" reaction to hovering over the bad decks after only 10 trials, long before conscious sensation that the decks are bad. By contrast, patients with OFC dysfunction never develop this physiological reaction to impending punishment. Bechara and his colleagues explain this in terms of the somatic markers hypothesis. The Iowa gambling task is currently being used by a number of research groups using fMRI to investigate which brain regions are activated by the task in healthy volunteers as well as clinical groups with conditions such as schizophrenia and obsessive compulsive disorder.

Faux pas test

This is a series of vignettes recounting a social occasion during which someone said something that should not have been said, or an awkward occurrence. The participant's task is to identify what was said that was awkward, why it was awkward, how people would have felt in reaction to the faux pas and a factual control question. Although first designed for use in people on the autism spectrum[10], the test is also sensitive to patients with OFC dysfunction, who cannot judge when something socially awkward has happened despite appearing to understand the story perfectly well.

Consequences of damage to the OFC

Destruction of the OFC through acquired brain injury typically leads to a pattern of disinhibited behaviour. Examples include swearing excessively, hypersexuality, poor social interaction, compulsive gambling, drug use (including alcohol and tobacco), and poor empathising ability. Disinhibited behaviour by patients with some forms of frontotemporal dementia is thought to be caused by degeneration of the OFC[11].

See also

- BELBIC

- Emotional Learning

- Phineas Gage

- Witzelsucht

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder

Additional images

References

- ^ a b c Kringelbach, M. L. (2005) "The orbitofrontal cortex: linking reward to hedonic experience." Nature Reviews Neuroscience 6: 691-702.

- ^ Fuster, J.M. The Prefrontal Cortex, (Raven Press, New York, 1997).

- ^ Uylings HB, Groenewegen HJ, Kolb B. (2003). Do rats have a prefrontal cortex? Behav Brain Res. 146(1-2):3-17. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2003.09.028 PMID 14643455

- ^ a b Bechara, A.; Damasio, A. R.; Damasio H. & Anderson, S.W. (1994) "Insensitivity to future consequences following damage to human prefrontal cortex". Cognition 50: 7-15.

- ^ Volz KG, Rübsamen R, von Cramon DY (September 2008). "Cortical regions activated by the subjective sense of perceptual coherence of environmental sounds: a proposal for a neuroscience of intuition". Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci 8 (3): 318–28. doi:10.3758/CABN.8.3.318. PMID 18814468. http://openurl.ingenta.com/content/nlm?genre=article&issn=1530-7026&volume=8&issue=3&spage=318&aulast=Volz.

- ^ J. Wilson, M. Jenkinson, I. E. T. de Araujo, Morten L. Kringelbach, E. T. Rolls, & Peter Jezzard (October 2002). "Fast, fully automated global and local magnetic field optimization for fMRI of the human brain". NeuroImage 17 (2): 967–976. doi:10.1016/S1053-8119(02)91172-9. PMID 12377170.

- ^ Kringelbach, M. L. and Rolls, E. T. (2004). "The functional neuroanatomy of the human orbitofrontal cortex: evidence from neuroimaging and neuropsychology". Progress in Neurobiology 72 (5): 341–372. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.03.006. PMID 15157726.

- ^ Jay A. Gottfrieda and David H. Zald (2005). "On the scent of human olfactory orbitofrontal cortex: Meta-analysis and comparison to non-human primates". Brain Research Reviews 50: 287–304.

- ^ Rolls, E. T.; Hornak, J.; Wade, D. & McGrath, J. (1994) "Emotion-related learning in patients with social and emotional changes associated with frontal lobe damage." J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 57: 1518-1524.

- ^ Stone, V.E.; Baron-Cohen, S. & Knight, R. T. (1998a) "Frontal Lobe Contributions to Theory of Mind." Journal of Medical Investigation 10: 640-656.

- ^ Snowden, J. S.; Bathgate, D.; Varma, A.; Blackshaw, A.; Gibbons, Z. C. & Neary. D. (2001) "Distinct behavioural profiles in frontotemporal dementia and semantic dementia". J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 70: 323-332.

External links

Anxiety disorder: Obsessive–compulsive disorder (F42, 300.3) History Yale–Brown Obsessive Compulsive ScaleBiology NeuroanatomyBasal ganglia (striatum) · Orbitofrontal cortex · Cingulate cortex · Brain-derived neurotrophic factorReceptorsSymptoms Obsessions (associative, diagnostic, injurious, scrupulous, pathogenic, sexual) · Compulsions (impulses, rituals, tics) · Thought suppression (avoidance) · Hoarding (animals, books, possessions)Treatment Mu opioidergicsNMDA glutamatergicsNK-1 tachykininergicsOtherBehavioralOrganizations Notable people Edna B. Foa · Stanley Rachman · Adam S. Radomsky · Jeffrey M. Schwartz · Susan Swedo · Jeff Bell · Emily ColasPopular culture LiteratureFictionalNonfictionEverything in Its Place · Just CheckingMediaRelated Obsessive–compulsive personality disorder · Obsessional jealousy · Purely Obsessional OCD · Social anxiety disorder · Tourette syndromeCategories:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.