- Celecoxib

-

Celecoxib

Systematic (IUPAC) name 4-[5-(4-methylphenyl)-3-(trifluoromethyl)

pyrazol-1-yl]benzenesulfonamideClinical data Trade names Celebrex AHFS/Drugs.com monograph MedlinePlus a699022 Pregnancy cat. B3(AU) C(US) Legal status ℞ Prescription only Routes Oral Pharmacokinetic data Bioavailability 40% Protein binding 97% (mainly to serum albumin) Metabolism Hepatic (mainly CYP2C9) Half-life ~11 h Excretion Renal 27%, faecal 57% Identifiers CAS number 169590-42-5

ATC code L01XX33 M01AH01 PubChem CID 2662 DrugBank APRD00373 ChemSpider 2562

UNII JCX84Q7J1L

KEGG D00567

ChEBI CHEBI:41423

ChEMBL CHEMBL118

Chemical data Formula C17H14F3N3O2S Mol. mass 381.373 g/mol SMILES eMolecules & PubChem  (what is this?) (verify)

(what is this?) (verify)Celecoxib INN (

/sɛlɨˈkɒksɪb/) is a sulfa non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) and selective COX-2 inhibitor used in the treatment of osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, acute pain, painful menstruation and menstrual symptoms, and to reduce numbers of colon and rectum polyps in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. It is marketed by Pfizer. It is known under the brand name Celebrex or Celebra for arthritis and Onsenal for polyps. Celecoxib is available by prescription in capsule form.

/sɛlɨˈkɒksɪb/) is a sulfa non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) and selective COX-2 inhibitor used in the treatment of osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, acute pain, painful menstruation and menstrual symptoms, and to reduce numbers of colon and rectum polyps in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. It is marketed by Pfizer. It is known under the brand name Celebrex or Celebra for arthritis and Onsenal for polyps. Celecoxib is available by prescription in capsule form.Contents

Indications

Celecoxib is licensed for use in osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, acute pain, painful menstruation and menstrual symptoms, ankylosing spondylitis and to reduce the number of colon and rectal polyps in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. It was originally intended to relieve pain while minimizing the gastrointestinal adverse effects usually seen with conventional NSAIDs. In practice, its primary indication is in patients who need regular and long term pain relief: there is probably no advantage to using celecoxib for short term or acute pain relief over conventional NSAIDs, except in the situation where non-selective NSAIDs or aspirin cause cutaneous reactions (urticaria or "hives"). In addition, the pain relief offered by celecoxib is similar to that offered by paracetamol (acetaminophen).[1]

Fabricated efficacy studies

On March 11, 2009, Scott S. Reuben, former chief of acute pain at Baystate Medical Center, Springfield, Mass., revealed that data for 21 studies he had authored for the efficacy of the drug (along with others such as Vioxx) had been fabricated, the analgesic effects of the drugs being exaggerated. Dr. Reuben was also a former paid spokesperson for Pfizer. The retracted studies were not submitted to either the U.S. Food and Drug Administration or the European Union's regulatory agencies prior to the drug's approval. Pfizer issued a public statement declaring, "It is very disappointing to learn about Dr. Scott Reuben's alleged actions. When we decided to support Dr. Reuben's research, he worked for a credible academic medical center and appeared to be a reputable investigator." [2][3]

Availability

Pfizer sells celecoxib under the brand name Celebrex, and is available as oral capsules containing 50 mg, 100 mg, 200 mg or 400 mg of celecoxib.

Celecoxib is not currently available as a generic in the United States, because it is covered by unexpired Pfizer patents. However, in other countries, including India and the Philippines, it is legally available as a generic under the brand names Cobix', Celcoxx and Celexib.

XL Laboratories sells celecoxib under the brand name Selecap in Vietnam and the Philippines.

Dosing

The usual adult dose of celecoxib is 100 to 200 mg once or twice a day. The lowest effective dose should be used.

Adverse effects

Gastrointestinal ADRs

In theory the COX-2 selectivity should result in a significantly lower incidence of gastrointestinal ulceration than traditional NSAIDs. The main items of evidence cited to support this theory were the preliminary (6 month) results of the Celecoxib Long-term Arthritis Safety Study (CLASS) as published in 2000, which demonstrated a significant reduction in the combination of symptomatic ulcers plus ulcer complications in those taking celecoxib versus ibuprofen or diclofenac, provided they were not on aspirin (Silverstein et al., 2000). However, this was not significant at 12 months (full study length).

Special precaution

Patients with prior history of ulcer disease or GI bleeding. Moderate to severe hepatic impairment, GI toxicity can occur with or without warning symptoms in patients treated with NSAIDs

Allergy

Celecoxib contains a sulfonamide moiety and may cause allergic reactions in those allergic to other sulfonamide-containing drugs. This is in addition to the contraindication in patients with severe allergies to other NSAIDs. However, it has a low (reportedly 4%) chance of inducing cutaneous reactions among persons who have a history of such reactions to aspirin or non-selective NSAIDs.

Drug Interactions

Celecoxib is predominantly metabolized by cytochrome P450 2D6. Caution must be exercised with concomitant use of 2D6 inhibitors, such as fluconazole, which can greatly elevate celecoxib serum levels. In addition, celecoxib may antagonize or increase the risk of renal failure with angiotensin converting enzyme-inhibitors, such as lisinopril, and diuretics, such as hydrochlorothiazide.[4]

Pregnancy

Celecoxib is labeled as pregnancy category C. It is contraindicated during the third trimester of pregnancy due to teratogenic potential.[4]

Risk of heart attack and stroke

There has been much concern about the possibility of increased risk for heart attack and stroke in users of NSAID drugs, particularly COX-2 selective NSAIDs such as celecoxib, since the withdrawal of the COX-2 inhibitor rofecoxib (Vioxx) in 2004. Like all NSAIDs on the U.S. market, celecoxib carries an FDA-mandated "black box warning" for cardiovascular and gastrointestinal risk. In February 2007, the American Heart Association warned that celecoxib should be used "as a last resort on patients who have heart disease or a risk of developing it", and suggested that paracetamol (acetaminophen), or certain older NSAIDs, such as naproxen, may be safer choices for chronic pain relief in these patients.[5]

The cardiovascular risks of celecoxib are controversial, with apparently contradictory data produced from different clinical trials. In December 2004, "APC", the first of two trials of celecoxib for colon cancer prevention, found that long-term (33 months) use of high-dose Celebrex (400 and 800 mg daily) demonstrated an increased cardiovascular risk compared with placebo.[6] A similar trial, named PreSAP, did not demonstrate an increased risk.[7] Still, the APC trial, combined with the recent Vioxx findings, suggested that there might be serious cardiovascular risks specific to the COX-2 inhibitors. On the other hand, a large Alzheimer's prevention trial, called ADAPT, was terminated early after preliminary data suggested that the nonselective NSAID naproxen, but not celecoxib, was associated with increased cardiovascular risk.[8] In 2005, a study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine found that cardiovascular effects of COX-2 inhibitors differ, depending on the drug.[9] Other COX-2 selective inhibitors, such as rofecoxib, have significantly higher myocardial infarction rates than celecoxib.[10] In April 2005, after an extensive review of data, the FDA concluded that it was likely "that there is a 'class effect' for increased CV risk for all NSAIDs".[11] In a 2006 meta-analysis of randomized control studies, the cerebrovascular events associated with COX-2 inhibitors were examined, but no significant risks were found when compared to non-selective NSAIDs or placebos.[12]

Two studies on the cardiovascular risks of celecoxib and other NSAIDs were meta-analyses, published in 2006. The first of these, published in the British Medical Journal, looked at the incidence of cardiovascular events in all previous randomized controlled trials of COX-2 inhibitors, as well as some trials of other NSAIDs. The authors concluded that a significant increased risk did exist for celecoxib, as well as some other selective and nonselective NSAIDS. However, the increased cardiovascular risk in celecoxib was noted only at daily doses of 400 mg or greater.[13] A second meta-analysis published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, which included observational rather than randomized studies (mostly at lower doses) did not find an increased cardiovascular risk of celecoxib vs placebo.[14]

The Vioxx Gastrointestinal Outcomes Research (VIGOR) trial presented a five-fold increase in atherothrombotic cardiovascular events associated with rofecoxib compared to naproxen.[15] Although, the Celecoxib Long-Term Arthritis Safety Study (CLASS) did not present an increase in occurrence of such events, many experts believe that the risk associated with rofecoxib long-term use also applies to celecoxib based on the pharmacology in three distinct mechanisms.[15] It is suggested that prostacyclin (PGI2) inhibition with relatively unopposed platelet-derived thromboxane (TxA2) generation may lead to thrombotic risks. PGI2 from endothelial cells by COX-2 catalysis has anti-aggregating, anti-proliferative, and vasodilating properties. Conversely, TxA2 from platelets maintain vascular homeostasis by irreversible platelet aggregating, vasoconstricting, and smooth muscle proliferating properties. The imbalance of PGI2 may promote TxA2 thrombosis.[15] In addition, COX-2 selective inhibitors can elevate blood pressure by allowing a normal amount of the vasoconstrictor, TxA2, and a stark decrease in the levels of the vasodilator, PGI2.,[16][17] Furthermore, a third postulate for promoting atherothombotic events includes that the upregulation of COX-2 plays a key role in cardioprotection of the last phase of ischemic preconditioning. Due to the controversy, it is advised that prescribers use caution when prescribing celecoxib and present rational care plans that demonstrate a clear indication for the medication.

To establish more conclusively the true cardiovascular risk profile of celecoxib, Pfizer agreed to fund a large, randomized trial specifically designed for that purpose. The trial, centered at the Cleveland Clinic, with a planned enrollment of 20,000 high-risk patients. Celecoxib will be compared with the non-selective NSAIDS naproxen and ibuprofen.[18] Since all patients have arthritis, ethical considerations make it difficult to have a placebo group. This trial has began enrollment in 2006 according to the Clinical Trials database, and is not scheduled to be completed until May 2014. Ultimately, this trial will help answer the question as to whether Celebrex has a riskier cardiovascular profile compared with naproxen or ibuprofen.

Pharmacology

Celecoxib is a highly selective COX-2 inhibitor and primarily inhibits this isoform of cyclooxygenase (and thus causes inhibition of prostaglandin production), whereas nonselective NSAIDs (like asprin, naproxen and ibuprofen) inhibit both COX-1 and COX-2. COX-1, traditionally defined as a constitutively-expressed “housekeeping” enzyme, is the only isoenzyme found in platelets and plays a role in the protection of the gastrointestinal mucosa, renal hemodynamics, and platelet thrombogenesis.[19] COX-2, on the contrary, is extensively expressed in cells involved in inflammation and is upregulated by bacterial lipopolysaccharides, cytokines, growth factors, and tumor promoters.[20] Celecoxib is approximately 10-20 times more selective for COX-2 inhibition over COX-1.[19] It binds with its polar sulfonamide side chain to a hydrophilic side pocket region close to the active COX-2 binding site.[21] In theory, this selectivity allows celecoxib and other COX-2 inhibitors to reduce inflammation (and pain) while minimizing gastrointestinal adverse drug reactions (e.g. stomach ulcers) that are common with non-selective NSAIDs.

Celecoxib inhibits COX-2 without affecting COX-1. COX-1 is involved in synthesis of prostaglandins and thromboxane, but COX-2 is only involved in the synthesis of prostaglandin. Therefore, inhibition of COX-2 inhibits only prostaglandin synthesis without affecting thromboxane (TXA2) and thus offer no cardioprotective effects of non-selective NSAIDs.

Medicinal chemistry

Synthesis

The synthesis of celecoxib was first described in 1997 by a team of researchers at Searle Research and Development. Celecoxib is synthesized by a Claisen condensation reaction of an acetophenone with N-(trifluoroacetyl)imidazole catalyzed by the strong base, sodium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide to produce a 1,3-dicarbonyl adduct.[22] Condensation of the diketone with (4-sulfamoylaphenyl)hydrazine produces the 1,5-diarylpyrazole drug moiety.

Structure-Activity Relationship

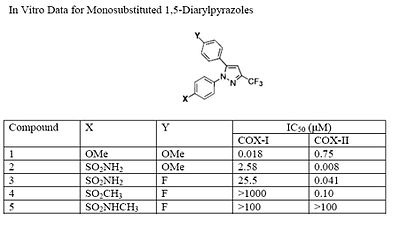

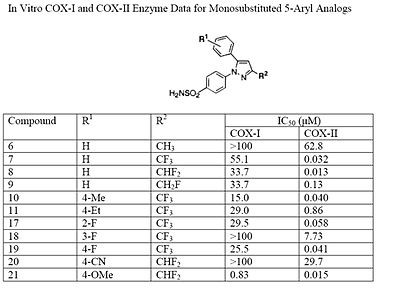

The Searle research group found that the two appropriately substituted aromatic rings must reside on adjacent positions about the central ring for adequate COX-2 inhibition. Various modifications can be made to the 1,5-diarylpyrazole moiety to deduce the structure-activity relationship of celecoxib.[22] It was found that a para-sulfamoylphenyl at position 1 of the pyrazole has a higher potency for COX-2 selective inhibition than a para-methoxyphenyl (see structures 1 and 2, below). In addition, it is known that a 4-(methylsulfonyl)phenyl or 4-sulfamoylphenyl is necessary for COX-2 inhibition. For instance, replacing either of these entities with a –SO2NHCH3 substituent diminishes COX-2 inhibitory activity as noted with a very high inhibitory concentration-50 (see structures 3 - 5). At the 3-position of the pyrazole, a trifluoromethyl or difluoromethyl provides superior selectivity and potency compared to a fluoromethyl or methyl substitution (see structures 6 – 9).[22]

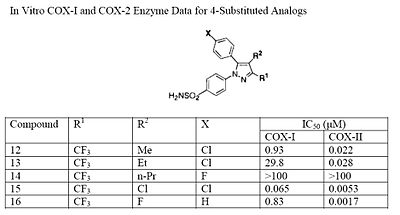

The fourth position of the pyrazole is readily affected by steric hindrance such that increasing the bulkiness of the substitution starkly decreases the potency. For example, by progressively increasing the size of R1, from a methyl to propyl, the potency for COX-2 inhibition decreases especially with moieties larger than an ethyl (see structures 10-12). In addition, incorporating a halo-atom at this position provides significantly potent COX-2 inhibition (see structures 13 and 14). While it is known that there must be an aromatic system at the fifth position of the pyrazole, optimizing this substituent is difficult since it is not known what combination of modifications will provide the highest potency and selectivity due to the flexible nature of the 5-aryl system. It was found that substitutions at either the para (4-substitution) or ortho (2-substitution) sites have higher potency than meta (3-substitution) sites (see structures 15-17).

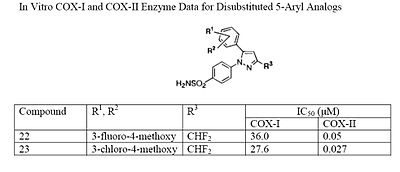

Electron withdrawing groups, such as –CN, at these positions have poor COX-1 and COX-2 inhibition; however, electron donating groups, such as methoxyl, have substantial COX-1 and COX-2 inhibitory effects which makes it inefficient as a COX-2 selective inhibitor (see structures 18 and 19 ). The strong COX-1 inhibition of the para-methoxyl can be corrected by substituting a halo-atom at the alpha position. For instance, the introduction of a 3-fluoro or 3-chloro decreases COX-1 inhibition by 43- and 33-folds, respectively (see structures 20 and 21). It is necessary to consider the steric hindrance created by a para-substitution of the 5-aromatic system. Consider the COX-2 inhibitory capacity of the 4-methyl and 4-ethyl modifications: 4-methyl can inhibit COX-2 such that the IC50 is 0.040μM while that of the 4-ethyl is 0.86μM which means that the 4-methyl substituent is at least 20-fold more potent (see structures 22 and 23).

Celecoxib is compound 22; the 4-sulfamoylphenyl on the 1-pyrazol substituent is required for COX-2 inhibition and the 4-methyl on the 5-pyrazol system has low steric hindrance to maximize potency while the 3-trifluoromethyl group provides superior selectivity and potency.[22] To explain the selectivity of celecoxib, it is necessary to analyze the free energy of binding difference between the drug molecule and COX-1 compared to COX-2 enzymes. The structural modifications highlight the importance of binding to residue 523 in the side binding pocket of the cyclooxygenase enzyme, which is an isoleucine in COX-1 and a valine in COX-2.[23] It appears that this mutation contributes to COX-2 selectivity by creating steric hindrance between the sulfonamide oxygen and the methyl group of Ile523 that effectively destabilizes the celecoxib-COX-1 complex. .[23] Thus it is reasonable to expect COX-2 selective inhibitors to be more bulky than non-selective NSAIDs.

History

Celecoxib was developed by G. D. Searle & Company and co-promoted by Monsanto Company (parent company of Searle) and Pfizer under the brand name Celebrex. Monsanto merged with Pharmacia, from which the Medical Research Division was acquired by Pfizer, giving Pfizer ownership of Celebrex. The drug was at the core of a major patent dispute that was resolved in Searle's favor (later Pfizer) in 2004. In University of Rochester v. G.D. Searle & Co., 358 F.3d 916 (Fed. Cir. 2004), the University of Rochester claimed that United States Pat. No. 6,048,850 (which claimed a method of inhibiting COX-2 in humans using a compound, without actually disclosing what that compound might be) covered drugs such as celecoxib. The court ruled in favor of Searle, holding in essence that the University had claimed a method requiring, yet provided no written description of, a compound that could inhibit COX-2 and therefore the patent was invalid.

After the withdrawal of rofecoxib (Vioxx) from the market in September 2004, Celebrex enjoyed a robust increase in sales. However, the results of the APC trial in December of that year raised concerns that Celebrex might carry risks similar to those of Vioxx, and Pfizer announced a moratorium on direct-to-consumer advertising of Celebrex soon afterwards. After a significant drop, sales of Celebrex have recovered, and reached $2 billion in 2006.[5] Pfizer resumed advertising Celebrex in magazines in 2006,[24] and resumed television advertising in April 2007 with an unorthodox, 2½ minute advertisement which extensively discussed the adverse effects of Celebrex in comparison with other anti-inflammatory drugs. The ad drew criticism from the consumer advocacy group Public Citizen, which called the ad's comparisons misleading.[25] Pfizer has responded to Public Citizen's concerns with assurances that they are truthfully advertising the risk and benefits of Celebrex as set forth by the FDA.

In late 2007, Pfizer released another U.S. television ad for Celebrex, which also discussed celecoxib's adverse effects in comparison with those of other anti-inflammatory drugs.

Dr. Simmons of Brigham Young University, who discovered the COX-2 enzyme, is suing Pfizer to be credited with discovery of the technique in 1989 that eventually led to the drug, and for $1 billion USD. The company has made about $30 billion from the drug as of 2006. [26]

Research into cancer prevention

The role that celecoxib might have in reducing the rates of certain cancers has been the subject of many studies. However, given the side effects of anti-COX-2 on rates of heart disease, there is no current medical recommendation to use this drug for cancer reduction.

- Colorectal cancer risk is clearly reduced in people regularly taking a NSAID like aspirin or celecoxib. In addition, some epidemiological studies, and most preclinical studies pointed out that specific COX-2 inhibitors like celecoxib are more potent and less toxic than "older" NSAIDs. Twelve carcinogenesis studies support that celecoxib is strikingly potent to prevent intestinal cancer in rats or mice (data available on the Chemoprevention Database). Small-scale clinical trials in very high risk people (belonging to FAP families) also indicate that celecoxib can prevent polyp growth. Hence large-scale randomized clinical trials were undertaken and results published by N. Arber and M. Bertagnolli in the New England Journal of Medicine, August 2006.[6] Results show a 33 to 45% polyp recurrence reduction in people taking 400–800 mg celecoxib each day. However, serious cardiovascular events were significantly more frequent in the celecoxib-treated groups (see above, cardiovascular toxicity). Aspirin shows a similar (and possibly larger) protective effect,[27][28][29] has demonstrated cardioprotective effects and is significantly cheaper, but there have been no head-to-head clinical trials comparing the two drugs.

Research into cancer treatment

Different from cancer prevention, cancer treatment is focused on the therapy of tumors that have already formed and have established themselves inside the patient. Many studies are ongoing to determine whether celecoxib might be useful for this latter condition.[30] However, during molecular studies in the laboratory, it became apparent that celecoxib could interact with other intracellular components besides its most famous target, cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2). The discovery of these additional targets has generated much controversy, and the initial assumption that celecoxib reduces tumor growth primarily via the inhibition of COX-2 became contentious.[31]

Certainly, the inhibition of COX-2 is paramount for the anti-inflammatory and analgesic function of celecoxib. However, whether inhibition of COX-2 also plays a dominant role in this drug’s anticancer effects is unclear. For example, a recent study with malignant tumor cells showed that celecoxib could inhibit the growth of these cells in vitro, but COX-2 played no role in this outcome; even more strikingly, the anticancer effects of celecoxib were also obtained with the use of cancer cell types that don’t even contain COX-2.[32]

Additional support for the idea that other targets besides COX-2 are important for celecoxib's anticancer effects has come from studies with chemically modified versions of celecoxib. Several dozen analogs of celecoxib were generated with small alterations in their chemical structures.[33] Some of these analogs retained COX-2 inhibitory activity, whereas many others didn't. However, when the ability of all these compounds to kill tumor cells in cell culture was investigated, it turned out that the antitumor potency did not at all depend on whether or not the respective compound could inhibit COX-2, showing that inhibition of COX-2 was not required for the anticancer effects.[33][34] One of these compounds, 2,5-dimethyl-celecoxib, which entirely lacks the ability to inhibit COX-2, actually turned out to display stronger anticancer activity than celecoxib itself.[35]

Research into adhesion prevention

Celocoxib may prevent intra-abdominal adhesion formation. Adhesions are a common complication of surgery, especially abdominal surgery, and major cause of bowel obstruction and infertility. Publishing in 2005, researchers in Boston noticed a "dramatic" reduction in post-surgical adhesions in mice taking the drug celecoxib.[36] Multi-institutional trials in adult human patients are planned.[37] The initially suggested course of treatment is a mere 7–10 days following surgery.[38]

See also

- Tilmacoxib

- COX-2 selective inhibitor

- Cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitors: drug discovery and development

References

- Sources

- Malhotra S, Shafiq N, Pandhi P (2004). "COX-2 inhibitors: a CLASS act or Just VIGORously promoted". Medscape General Medicine 6 (1): 6. PMC 1140734. PMID 15208519. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/47342.

- Silverstein FE, Faich G, Goldstein JL, et al. (September 2000). "Gastrointestinal toxicity with celecoxib vs nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: the CLASS study: A randomized controlled trial. Celecoxib Long-term Arthritis Safety Study". Journal of the American Medical Association 284 (10): 1247–55. doi:10.1001/jama.284.10.1247. PMID 10979111. http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=10979111.

- Solomon SD, McMurray JJ, Pfeffer MA, et al. (March 2005). "Cardiovascular risk associated with celecoxib in a clinical trial for colorectal adenoma prevention". New England Journal of Medicine 352 (11): 1071–80. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa050405. PMID 15713944.

- [21]

- Notes

- ^ Yelland MJ, Nikles CJ, McNairn N, Del Mar CB, Schluter PJ, Brown RM (2007). "Celecoxib compared with sustained-release paracetamol for osteoarthritis: a series of n-of-1 trials". Rheumatology 46 (1): 135–40. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kel195. PMID 16777855.

- ^ Winstein, Keith J. (March 11, 2009). "Top Pain Scientist Fabricated Data in Studies, Hospital Says". The Wall Street Journal. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB123672510903888207.html?mod=loomia&loomia_si=t0:a16:g2:r1:c0.0270612:b22894832.

- ^ "Associated Press, Mar 11, 2009, Mass. doctor accused of faking pain pill data". http://www.google.com/hostednews/ap/article/ALeqM5jjpBsTFN9SEtQu-xyDltivC2GJ8AD96S2KVO0.

- ^ a b Lexi-Comp,Inc. (Lexi-Drugs). Hudson, Ohio: Lexi-Comp,Inc.,2010. Electronic.

- ^ a b CNBC.com (2007-02-26). "Pfizer's Celebrex Should Be 'Last Resort', Heart Group Says". CNBC.com. http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/17349356.

- ^ a b Bertagnolli M, Eagle C, Zauber A, Redston M, Solomon S, Kim K, Tang J, Rosenstein R, Wittes J, Corle D, Hess T, Woloj G, Boisserie F, Anderson W, Viner J, Bagheri D, Burn J, Chung D, Dewar T, Foley T, Hoffman N, Macrae F, Pruitt R, Saltzman J, Salzberg B, Sylwestrowicz T, Gordon G, Hawk E (2006). "Celecoxib for the prevention of sporadic colorectal adenomas". New England Journal of Medicine 355 (9): 873–84. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa061355. PMID 16943400.

- ^ Arber N, Eagle C, Spicak J, Rácz I, Dite P, Hajer J, Zavoral M, Lechuga M, Gerletti P, Tang J, Rosenstein R, Macdonald K, Bhadra P, Fowler R, Wittes J, Zauber A, Solomon S, Levin B (2006). "Celecoxib for the prevention of colorectal adenomatous polyps". New England Journal of Medicine 355 (9): 885–95. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa061652. PMID 16943401.

- ^ Adapt Research, Group (2006). "Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events in the randomized, controlled Alzheimer's Disease Anti-Inflammatory Prevention Trial (ADAPT)". Public Library of Science Clinical Trials 1 (7): e33. doi:10.1371/journal.pctr.0010033. PMC 1851724. PMID 17111043. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1851724.

- ^ Kimmel SE, Berlin JA, Reilly M, Jaskowiak J, Kishel L, Chittams J, Strom BL. Patients Exposed to Rofecoxib and Celecoxib Have Different Odds of Nonfatal Myocardial Infarction. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:157-164.

- ^ Mukherjee D, Nissen SE, Topol EJ. Inhibitors Risk of Cardiovascular Events Associated With Selective COX-2 Inhibitors. JAMA. 2001;286(8):954-959 (doi:10.1001/jama.286.8.954).

- ^ Jenkins JK, Seligman PJ. (2005-04-06). "Analysis and recommendations for Agency action regarding non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cardiovascular risk [decision memorandum"] (PDF). FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. http://www.fda.gov/cder/drug/infopage/cox2/NSAIDdecisionMemo.pdf.

- ^ Chen LC, Ashcroft DM. Do selective COX-2 inhibitors increase the risk of cerebrovascular events? A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics (2006) 31, 565–576.

- ^ Kearney P, Baigent C, Godwin J, Halls H, Emberson J, Patrono C (2006). "Do selective cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors and traditional non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs increase the risk of atherothrombosis? Meta-analysis of randomised trials". British Medical Journal 332 (7553): 1302–8. doi:10.1136/bmj.332.7553.1302. PMC 1473048. PMID 16740558. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1473048.

- ^ McGettigan P, Henry D (2006). "Cardiovascular risk and inhibition of cyclooxygenase: a systematic review of the observational studies of selective and nonselective inhibitors of cyclooxygenase 2". Journal of the American Medical Association 296 (13): 1633–44. doi:10.1001/jama.296.13.jrv60011. PMID 16968831.

- ^ a b c Pitt B, Pepine C, Willerson JT. Cyclooxygenase-2 Inhibition and Cardiovascular Events.Circulation. 2002; 106: 167-169.

- ^ Lee YH, Ji JD, Song GG. Adjusted Indirect Comparison of Celecoxib versus Rofecoxib on Cardiovascular Risk. Rheumatology International Clinical and Experimental Investigations. 2007 March; 27(5): 477-482.

- ^ Collins R, Peto R, MacMohan S, et al. Blood Pressure, Stroke, and Coronary Heart Disease.Part 2, Short-Term Reductions in Blood Pressure: Overview of Randomised Drug Trials in Their Epidemiological Context. Lancet. 1990 June 23; 335 (8693): 827-38.

- ^ "PRECISION : Prospective Randomized Evaluation of Celecoxib Integrated Safety vs Ibuprofen Or Naproxen". ClinicalTrials.gov. National Library of Medicine. 2006-12-07. http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct/show/NCT00346216?order=13.

- ^ a b Katzung, Bertram G. BASIC AND CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY. 10TH EDIDITION. McGraw Hill. page 579.

- ^ Shi S and Koltz U. Clinical use and pharmacological properties of selective COX-2 inhibitors. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. Nov 13, 2007.

- ^ a b DiPiro, Joseph T., Robert L. Talbert, Gary C. Yee, Gary R. Matzke, Barbara G. Wells, and L. Michael Posey. Pharmacotherapy A Pathophysiologic Approach (Pharmacotherapy (Dipiro) Pharmacotherapy (Dipiro)). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical, 2008. Print.

- ^ a b c d Penning TD, Talley JJ, Bertenshaw SR et al. (1997). "Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of the 1.5 Diarylpyrazole Class of Cyclooxygenase-2 Inhibitors: Identification of 4-[5-(4-Methylphenyl)-3-(trifluoromethyl)-1H-pyrazole-1-yl]benzenesulfonamide (SC-58634, Celecoxib)". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 40 (9): 1347–1365. doi:10.1021/jm960803q. PMID 9135032.

- ^ a b Price MLP, Jorgensen WL. Rationale for the Observed COX-2/COX-1 Selectivity of Celecoxibfrom Monte Carlo Simulations. Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry Lectures. 2001; 11: 1541-1544.

- ^ Berenson A (April 29, 2006). "Celebrex Ads Are Back, Dire Warnings and All". New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/29/business/media/29celebrex.html?ex=1176350400&en=d4bd60db69c60257&ei=5070.

- ^ Saul S (April 10, 2007). "Celebrex Commercial, Long and Unconventional, Draws Criticism". New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2007/04/10/business/media/10celebrex.html?ref=business.

- ^ Linda Thomson (October 28, 2009). "Judge orders Pfizer to pay BYU $852K for suit delays". Deseret News. http://www.deseretnews.com/article/705340277/Judge-orders-Pfizer-to-pay-BYU-852K-for-suit-delays.html.

- ^ Baron JA, Cole BF, Sandler RS, et al. (2003). "A randomized trial of aspirin to prevent colorectal adenomas". New England Journal of Medicine 348 (10): 891–9. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa021735. PMID 12621133.

- ^ Sandler RS, Halabi S, Baron JA, et al. (2003). "A randomized trial of aspirin to prevent colorectal adenomas in patients with previous colorectal cancer". New England Journal of Medicine 348 (10): 883–90. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa021633. PMID 12621132.

- ^ Bosetti C, Talamini R, Franceschi S, Negri E, Garavello W, La Vecchia C (2003). "Aspirin use and cancers of the upper aerodigestive tract". British Journal of Cancer 88 (5): 672–4. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6600820. PMC 2376339. PMID 12618872. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2376339.

- ^ Dannenberg AJ, Subbaramaiah K (December 2003). "Targeting cyclooxygenase-2 in human neoplasia: rationale and promise". Cancer Cell 4 (6): 431–6. doi:10.1016/S1535-6108(03)00310-6. PMID 14706335. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1535610803003106.

- ^ Schönthal AH (December 2007). "Direct non-cyclooxygenase-2 targets of celecoxib and their potential relevance for cancer therapy". Br. J. Cancer 97 (11): 1465–8. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6604049. PMC 2360267. PMID 17955049. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2360267.

- ^ Chuang, Huan-Ching; Kardosh, A; Gaffney, KJ; Petasis, NA; Schönthal, AH (2008). "COX-2 inhibition is neither necessary nor sufficient for celecoxib to suppress tumor cell proliferation and focus formation in vitro". Molecular Cancer 7 (1): 38. doi:10.1186/1476-4598-7-38. PMC 2396175. PMID 18485224. http://www.molecular-cancer.com/content/7/1/38.

- ^ a b Zhu J, Song X, Lin HP, et al. (December 2002). "Using cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors as molecular platforms to develop a new class of apoptosis-inducing agents". Journal of the National Cancer Institute 94 (23): 1745–57. PMID 12464646. http://jnci.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=12464646.

- ^ Schönthal AH, Chen TC, Hofman FM, Louie SG, Petasis NA (February 2008). "Celecoxib analogs that lack COX-2 inhibitory function: preclinical development of novel anticancer drugs". Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs 17 (2): 197–208. doi:10.1517/13543784.17.2.197. PMID 18230053.

- ^ Schönthal AH (2006). "Antitumor properties of dimethyl-celecoxib, a derivative of celecoxib that does not inhibit cyclooxygenase-2: implications for glioma therapy". Neurosurgical Focus 20 (4): E21. doi:10.3171/foc.2006.20.4.14. PMID 16709027.

- ^ Arin K. Greene, MD, MMSc,Ian P. J. Alwayn, MD, PhD, Vania Nose, MD, PhD, Evelyn Flynn, MA, David Sampson, BA, David Zurakowski, PhD, Judah Folkman, MD, and Mark Puder, MD (July 2005). "Prevention of Intra-abdominal Adhesions Using the Antiangiogenic COX-2 Inhibitor Celecoxib". Ann Surg. 242 (1): 140–146. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000167847.53159.c1. PMC 1357715. PMID 15973112. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1357715.

- ^ "Celebrex Prevents Adhesions After Surgery". Children's Hospital Boston. January 26, 2005. http://www.childrenshospital.org/newsroom/Site1339/mainpageS1339P1sublevel119.html. Retrieved 2009-03-11.

- ^ Viinikka, Tai (February 25, 2005). "COX-2 Inhibitors May Prevent Common Surgical Complication". Focus Online. Harvard Medical, Dental, and Public Health Schools. http://focus.hms.harvard.edu/2005/Feb25_2005/research_briefs.html. Retrieved 2009-03-11.

External links

- Celebrex website run by Pfizer

- FDA Alert for Practitioners on Celebrex (celecoxib), published December 17, 2004

- FDA Alert for Healthcare Professionals published July 4, 2005

- Largest systematic review of adverse renal and arrhythmia risk of Celecoxib and other COX-2 inhibitors, in JAMA 2006

- U.S. National Library of Medicine: Drug Information Portal - Celecoxib

Anti-inflammatory products (M01A) Pyrazolidine/Butylpyrazolidines Ampyrone • Clofezone • Kebuzone • Metamizole • Mofebutazone • Oxyphenbutazone • Phenazone • Phenylbutazone • Sulfinpyrazone • Feprazone •Acetic acid derivatives

and related substancesAceclofenac • Acemetacin • Alclofenac • Bromfenac • Bumadizone • Bufexamac • Diclofenac • Difenpiramide • Etodolac • Fentiazac • Indometacin • Ketorolac • Lonazolac • Oxametacin • Proglumetacin • Sulindac • Tolmetin • Zomepirac • AmfenacOxicams Propionic acid derivatives Alminoprofen • Benoxaprofen • Dexibuprofen • Dexketoprofen • Fenbufen • Fenoprofen • Flunoxaprofen • Flurbiprofen • Ibuprofen • Ibuproxam • Indoprofen • Ketoprofen • Naproxen • Oxaprozin • Pirprofen • Suprofen • Tiaprofenic acidFenamates Coxibs Other Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) products (primarily M01A and M02A, also N02BA) Salicylates Aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid) • Aloxiprin • Benorylate • Diflunisal • Ethenzamide • Magnesium salicylate • Methyl salicylate • Salsalate • Salicin • Salicylamide • Sodium salicylateArylalkanoic acids Diclofenac • Aceclofenac • Acemetacin • Alclofenac • Bromfenac • Etodolac • Indometacin • Indometacin farnesil • Nabumetone • Oxametacin • Proglumetacin • Sulindac • Tolmetin2-Arylpropionic acids

(profens)Ibuprofen • Alminoprofen • Benoxaprofen • Carprofen • Dexibuprofen • Dexketoprofen • Fenbufen • Fenoprofen • Flunoxaprofen • Flurbiprofen • Ibuproxam • Indoprofen† • Ketoprofen • Ketorolac • Loxoprofen • Miroprofen • Naproxen • Oxaprozin • Pirprofen • Suprofen • Tarenflurbil • Tiaprofenic acidN-Arylanthranilic acids

(fenamic acids)Pyrazolidine derivatives Oxicams COX-2 inhibitors Celecoxib • Deracoxib‡ • Etoricoxib • Firocoxib‡ • Lumiracoxib† • Parecoxib • Rofecoxib† • Valdecoxib†Sulfonanilides Topically used products Bendazac • Diclofenac • Etofenamate • Felbinac • Flurbiprofen • Ibuprofen • Indometacin • Ketoprofen • Naproxen • Piroxicam • SuprofenCOX-inhibiting nitric oxide donators Others Items listed in bold indicate initially developed compounds of specific groups. †Withdrawn drugs. ‡Veterinary use medications.Analgesics (N02A, N02B) Opioids

See also: Opioids templateOpium & alkaloids thereofSemi-synthetic opium

derivativesSynthetic opioidsAlphaprodine • Anileridine • Butorphanol • Dextromoramide • Dextropropoxyphene • Dezocine • Fentanyl • Ketobemidone • Levorphanol • Methadone • Meptazinol • Nalbuphine • Pentazocine • Propoxyphene • Propiram • Pethidine • Phenazocine • Piminodine • Piritramide • Tapentadol • Tilidine • Tramadol

Pyrazolones Cannabinoids Anilides Non-steroidal

anti-inflammatories

See also: NSAIDs templatePropionic acid classFenoprofen • Flurbiprofen • Ibuprofen# • Ketoprofen • Naproxen • Oxaprozin

Oxicam classAcetic acid classDiclofenac • Indometacin • Ketorolac • Nabumetone • Sulindac • Tolmetin

Celecoxib • Rofecoxib • Valdecoxib • Parecoxib • Lumiracoxib

Anthranilic acid

(fenamate) classMeclofenamate • Mefenamic acid

SalicylatesAspirin (Acetylsalicylic acid)# • Benorylate • Diflunisal • Ethenzamide • Magnesium salicylate • Salicin • Salicylamide • Salsalate • Trisalate • Wintergreen (Methyl salicylate)

Atypical, adjuvant and potentiators,

Metabolic agents and miscellaneousAmitryptiline • Befiradol • Bicifadine • Carisoprodol • Camphor • Cimetidine • Clonidine • Chlorzoxazone • Cyclobenzaprine • Duloxetine • Esreboxetine • Flupirtine • Gabapentin • Glafenine • Hydroxyzine • Ketamine • Menthol • Mephenoxalone • Methocarbamol • Nefopam • Orphenadrine • Pregabalin • Proglumide • Scopolamine • Tebanicline • Trazodone • Gabapentin enacarbil • ZiconotideCategories:- Antineoplastic drugs

- COX-2 inhibitors

- Organofluorides

- Pfizer

- Pyrazoles

- Sulfonamides

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.