- Menstruation

-

Not to be confused with "mensuration", a mathematical and a forestry term meaning measurement.See also: Menstrual cycle and Menstruation (mammal)

Menstruation is the shedding of the uterine lining (endometrium). It occurs on a regular basis in reproductive-age females of certain mammal species. This article focuses on human menstruation.

Overview

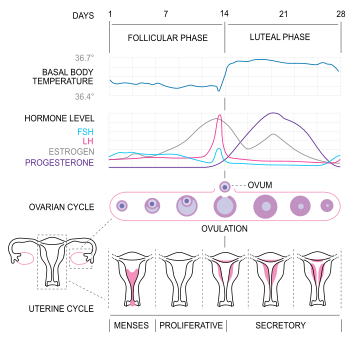

Regular menstruation (also called eumenorrhea) lasts for a few days, usually 3 to 5 days, but anywhere from 2 to 8 days is considered normal.[1] The average menstrual cycle is 28 days long from the first day of one menstrual period to the first day of the next. A normal menstrual cycle is typically between 21 and 35 days between menstrual periods. [2]

The average blood loss during a monthly menstrual period is 35 milliliters (or 4 to 6 tablespoons of menstrual fluid) with 10-80 milliliters considered typical. Menstrual fluid is the correct name for the menstrual flow, although many people refer to it as menstrual blood. Menstrual fluid in fact contains some blood, as well as cervical mucus, vaginal secretions, and endometrial tissue. Menstrual fluid is reddish-brown, a slightly darker colour than blood. [3]

Many women also notice shedding of the uterus's endometrium lining during menstruation. The shed endometrium lining appears as small pieces of tissue mixed with the blood. These pieces of tissue are often called menstrual clots (although they are pieces of the endometrium, and are not true blood clots) and are common; they more frequently occur in women who experience a heavier-than-average menstrual flow.[4] Sometimes this is incorrectly thought to indicate an early-term miscarriage of an embryo. An enzyme called plasmin — contained in the endometrium — tends to inhibit the blood from clotting. Because of this blood loss, premenopausal women have higher dietary requirements for iron to prevent iron deficiency.

The first experience of a menstrual period during puberty is called menarche. Menarche typically occurs between ages 10 and 17. [5] Perimenopause is when fertility in a woman declines, and menstruation may occur infrequently in the years leading up to menopause, when a woman stops menstruating completely and is no longer fertile. Menopause typically occurs between the late 40s and 50s[6] in Western countries.

Physical experience

See also: Premenstrual syndromeIn most women, various physical changes are brought about by natural fluctuations in hormone levels during the menstrual cycle, and by muscle contractions (menstrual cramping) involving the uterus that can precede or accompany menstruation. Women may notice water retention, changes in sex drive, fatigue, breast tenderness, or nausea. Breast swelling and discomfort may be caused by premenstrual water retention. Binge eating occurs in a minority of menstruating women.[7] Usually, such sensations are mild, and some women notice very few physical changes associated with menstruation. A healthy diet, reduced consumption of salt, caffeine and alcohol, and regular exercise are often effective in controlling these physical changes.[8] Typical physical changes related to menstruation are not ordinarily considered to be true Premenstrual Syndrome. However, it is common for non-medical people to refer to these physical changes colloquially as "PMS symptoms". The sensations experienced vary from woman to woman and from cycle to cycle.

Painful menstrual cramps

Many women experience painful uterine cramps during menstruation. The muscles of the uterus, and abdominal muscles surrounding the uterus, contract spasmodically to push the menstrual fluid out of the uterus. The contractions are produced by the tissue lining the uterus, which is believed to release an excess of fatty acids called prostaglandins that stimulate the muscles, leading to contractions. This is called primary dysmenorrhea. Primary dysmenorrhea usually begins within a year or two of menarche. It may continue until menopause, but many women find that symptoms of dysmenorrhea gradually subside after their mid-20s. If the pain occurs between menstrual periods, or lasts longer than the first few days of the period, it is called secondary dysmenorrhea.[9]

Symptoms of dysmenorrhea may become debilitating in some women. It is unknown why this occurs in some women and not others. Severe symptoms may include pain spreading to hips, lower back and thighs, nausea and frequent diarrhea or constipation. Treatments target excess prostaglandin, using anti-prostaglandin medications or oral contraceptives. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDS), such as over-the-counter ibuprofen and naproxen, may ease symptoms.[10]

Emotional and psychological experience

Some women experience emotional disturbances associated with menstruation. These range from the irritability, to tiredness, or "weepiness" (i.e. easily-provoked tearfulness). A similar range of emotional effects and mood swings is associated with pregnancy.[11] The prevalence of PMS is estimated to be between 3%[12] and 30%.[13] More severe symptoms of anxiety or depression may be signs of Premenstrual Syndrome. Rarely, in individuals susceptible to psychotic episodes, menstruation may be a trigger (menstrual psychosis).

Premenstrual Syndrome

In some cases, stronger physical and emotional or psychological sensations may become debilitating, and include significant menstrual pain (dysmenorrhea), migraine headaches, and severe depression. Dysmenorrhea, or severe uterine pain, is particularly common for adolescents and young women (one study found that 67.2% of girls aged 13–19 suffer from it).[14] This phenomenon is called Premenstrual Syndrome. More severe symptoms may be classified as Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD).

Menstrual disorders

It should be noted that there is a wide spectrum of differences between how women may experience menstruation. What may indicate a more serious physical problem for one woman, may be quite normal for another. There are several ways that a woman's menstrual cycle can differ from the norm, any of which should be discussed with a doctor to identify the underlying cause:

Symptom See article Infrequent periods Oligomenorrhea Short or extremely light periods Hypomenorrhea Too-frequent periods (defined as more frequently than every 21 days) Polymenorrhea Extremely heavy or long periods (one guideline is soaking a sanitary napkin or tampon every hour or so, or menstruating for longer than 7 days) Hypermenorrhea Extremely painful periods Dysmenorrhea Breakthrough bleeding (also called spotting) between periods; normal in many women Metrorrhagia Absent periods Amenorrhea Dysfunctional uterine bleeding is a hormonally caused bleeding abnormality. Dysfunctional uterine bleeding typically occurs in premenopausal women who do not ovulate normally (i.e. are anovulatory). All these bleeding abnormalities need medical attention; they may indicate hormone imbalances, uterine fibroids, or other problems. As pregnant patients may bleed, a pregnancy test forms part of the evaluation of abnormal bleeding.

Menstruation and pregnancy

Menstruation is the most visible phase of the menstrual cycle, and corresponds closely with the hormonal cycle, and is therefore used as the limit between cycles; Menstrual cycles are counted from the first day of menstrual bleeding, a point in time commonly termed last menstrual period (LMP). The time from LMP until ovulation is, on average, 14.6[15] days, but with substantial variation both between women and between cycles in any single woman, with an overall 95% prediction interval of 8.2 to 20.5[15] days.

During pregnancy and for some time after childbirth, menstruation is normally suspended; this state is known as amenorrhoea, i.e. absence of the menstrual cycle. If menstruation has not resumed, fertility is low during lactation. The average length of postpartum amenorrhoea is longer when certain breastfeeding practices are followed; this may be done intentionally as birth control.

Use of synthetic hormones to control menstruation

Since the late 1960s, many women have chosen to control the frequency of menstruation with long-acting hormonal birth control, often simply called 'the pill'. They are most often combined hormone pills containing estrogen and are taken in 28 day cycles, 21 hormonal pills with either a 7 day break from pills, or 7 placebo pills during which the woman menstruates. Hormonal contraception acts by using low doses of hormones to prevent ovulation, and thus prevent conception in sexually active women. But by using placebo pills for a 7-day span during the month, a regular menstrual period is still experienced.

Injections such as depo-provera became available in the 1960s. Progestogen implants such as Norplant in the 1980s and extended cycle combined oral contraceptive pills in the early 2000s.

Using synthetic hormones, it is possible for a woman to completely eliminate menstrual periods. [16] When using progestogen implants, menstruation may be reduced to 3 or 4 menstrual periods per year. By taking progestogen-only contraceptive pills (sometimes called the 'mini-pill') continuously without a 7-day span of using placebo pills, the menstrual period is eliminated entirely. Some women do this simply for convenience in the short-term,[17] while others prefer to eliminate periods altogether when possible.

Menstrual suppression

Some women use hormonal contraception in this way to eliminate periods for months or years at a time, a practise called menstrual suppression. When the first birth control pill was being developed, the researchers were aware that they could use the contraceptive to space menstrual periods up to 90 days apart, but they settled on a 28-day cycle that would mimic a natural menstrual cycle and produce monthly periods. The intention behind this decision was the hope of the inventor, John Rock, to win approval for his invention from the Roman Catholic Church. That attempt failed, but the 28-day cycle remained the standard when the pill became available to the public. [18] There is debate among medical researchers about the potential long-term impacts of these practises upon women's health. Some researchers point to the fact that historically, women have had far fewer menstrual periods throughout their lifetimes, a result of shorter life expectancies, as well as a greater length of time spent pregnant or breast-feeding, which reduced the number of periods experienced by women.[19] These researchers believe that the higher number of menstrual periods experienced by women in modern societies may have a negative impact upon women's health. On the other hand, some researchers believe there is a greater potential for negative impacts from exposing women perhaps unnecessarily to regular low doses of synthetic hormones over their reproductive years.[20] [21]

Menstrual products

Main article: Menstrual productMost women use something to absorb or catch their menses. There are a number of different methods available.

Reusable items:

- Reusable cloth pads are made of cotton (often organic), terrycloth, or flannel, and may be handsewn (from material or reused old clothes and towels) or storebought.

- Menstrual cups — A firm, flexible bell-shaped device worn inside the vagina to catch menstrual flow. Reusable versions include rubber or silicone cups.

- Sea sponges — Natural sponges, worn internally like a tampon to absorb menstrual flow.

- Padded panties — Reusable cloth (usually cotton) underwear with extra absorbent layers sewn in to absorb flow.

- Blanket, towel — (also known as a draw sheet) — large reusable piece of cloth, most often used at night, placed between legs to absorb menstrual flow.

- Menstrual cups — A firm, flexible cup-shaped device worn inside the vagina to catch menstrual flow. Sterilised after each period.

Disposable items:

A tampon.

- Sanitary napkins (Sanitary towels) or pads — Somewhat rectangular pieces of material worn in the underwear to absorb menstrual flow, often with "wings," pieces that fold around the undergarment and/or an adhesive backing to hold the pad in place. Disposable pads may contain wood pulp or gel products, usually with a plastic lining and bleached. Some sanitary napkins, particularly older styles, are held in place by a belt-like apparatus, instead of adhesive or wings.

- Tampons — Disposable cylinders of treated rayon/cotton blends or all-cotton fleece, usually bleached, that are inserted into the vagina to absorb menstrual flow.

- Padettes — Disposable wads of treated rayon/cotton blend fleece that are placed within the inner labia to absorb menstrual flow.

- Disposable menstrual cups — A firm, flexible cup-shaped device worn inside the vagina to catch menstrual flow. Disposable cups are made of soft plastic.

In addition to products to contain the menstrual flow, pharmaceutical companies likewise provide products — commonly non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) — to relieve menstrual cramps. Some herbs, such as dong quai, raspberry leaf and crampbark, are also claimed to relieve menstrual pain;[22] however there is no documented scientific evidence to prove this.[citation needed]

Culture and menstruation

Main article: Culture and menstruationMany religions have menstruation-related traditions. These may be bans on certain actions during menstruation (such as intercourse in orthodox Judaism and Islam), or rituals to be performed at the end of each menses (such as the mikvah in Judaism and the ghusl in Islam). Some traditional societies sequester females in residences, "menstrual huts", that are reserved for that exclusive purpose until the end of their menstrual period.

Evolution

All female placental mammals have a uterine lining that builds up when the animal is fertile, but is dismantled (menstruated) when the animal is infertile. Some anthropologists have questioned the energy cost of rebuilding the endometrium every fertility cycle. However, anthropologist Beverly Strassmann has proposed that the energy savings of not having to continuously maintain the uterine lining more than offsets energy cost of having to rebuild the lining in the next fertility cycle, even in species such as humans where much of the lining is lost through bleeding (overt menstruation) rather than reabsorbed (covert menstruation).[23][24] However, even in humans, much of it is re-absorbed.

Many have questioned the evolution of overt menstruation in humans and related species, speculating on what advantage there could be to losing blood associated with dismantling the endometrium rather than absorbing it, as most mammals do.

Beginning in 1971, some research suggested that menstrual cycles of co-habiting human females became synchronized. A few anthropologists hypothesized that in hunter-gatherer societies, males would go on hunting journeys whilst the females of the tribe were menstruating, speculating that the females would not have been as receptive to sexual relations while menstruating.[25][26] However, there is currently significant dispute as to whether menstrual synchrony exists.[27]

Humans do, in fact, reabsorb about two-thirds of the endometrium each cycle. Strassmann asserts that overt menstruation occurs not because it is beneficial in itself. Rather, the fetal development of these species requires a more developed endometrium, one which is too thick to reabsorb completely. Strassman correlates species that have overt menstruation to those that have a large uterus relative to the adult female body size.[28]

Further reading

- Howie, Gillian; Shail, Andrew (2005). Menstruation: A Cultural History. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 1-4039-3935-7. http://us.macmillan.com/menstruation.

- Knight, Chris (1995). Blood Relations: Menstruation and the Origins of Culture. New Haven and London: Yale University. ISBN 0-300-04911-0. http://www.chrisknight.co.uk/publications/.

- Museum of Menstruation

See also

Footnotes

- ^ The National Women's Health Information Center (April 2007). "What is a typical menstrual period like?". U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. http://www.4woman.gov/faq/menstru.htm#4. Retrieved 2005-06-11.

- ^ Karen J. Carlson, MD; Stephanie A. Eisenstat, MD; Terra Ziporyn, PhD (2004). The New Harvard Guide to Women's Health. Harvard University Press. pp. 381. ISBN 0674013433.

- ^ Karen J. Carlson, MD; Stephanie A. Eisenstat, MD; Terra Ziporyn, PhD (2004). The New Harvard Guide to Women's Health. Harvard University Press. pp. 381. ISBN 0674013433.

- ^ "Menstrual blood problems: Clots, color and thickness". WebMD. http://women.webmd.com/menstrual-blood-problems-clots-color-and-thickness. Retrieved September 20, 2011.

- ^ Karen J. Carlson, MD; Stephanie A. Eisenstat, MD; Terra Ziporyn, PhD (2004). The New Harvard Guide to Women's Health. Harvard University Press. pp. 381. ISBN 0674013433.

- ^ Karen J. Carlson, MD; Stephanie A. Eisenstat, MD; Terra Ziporyn, PhD (2004). The New Harvard Guide to Women's Health. Harvard University Press. pp. 381. ISBN 0674013433.

- ^ Price WA, Giannini AJ (November 1983). "Binge eating during menstruation". J Clin Psychiatry 44 (11): 431. PMID 6580290.

- ^ "Water retention: Relieve this premenstrual symptom". Mayo Clinic. http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/water-retention/WO00130. Retrieved September 20, 2011.

- ^ Karen J. Carlson, MD; Stephanie A. Eisenstat, MD; Terra Ziporyn, PhD (2004). The New Harvard Guide to Women's Health. Harvard University Press. pp. 379. ISBN 0674013433.

- ^ Karen J. Carlson, MD; Stephanie A. Eisenstat, MD; Terra Ziporyn, PhD (2004). The New Harvard Guide to Women's Health. Harvard University Press. pp. 379. ISBN 0674013433.

- ^ Giannini AJ, Price WA, Loiselle RH (June 1984). "beta-Endorphin withdrawal: a possible cause of premenstrual tension syndrome". Int J Psychophysiol 1 (4): 341–3. doi:10.1016/0167-8760(84)90028-X. PMID 6094401.

- ^ "NIH Press Release-Hormones Trigger PMS Symptoms - 21 January 1998". http://www.nih.gov/news/pr/jan98/nimh-21.htm. Retrieved 2008-02-28

- ^ Dean BB, Borenstein JE, Knight K, Yonkers K (2006). "Evaluating the criteria used for identification of PMS". J Womens Health (Larchmt) 15 (5): 546–55. doi:10.1089/jwh.2006.15.546. PMID 16796482

- ^ Sharma P, Malhotra C, Taneja DK, Saha R (2008). "Problems related to menstruation amongst adolescent girls". Indian J Pediatr 75 (2): 125–9. doi:10.1007/s12098-008-0018-5. PMID 18334791

- ^ a b Geirsson, R. T. (1991). "Ultrasound instead of last menstrual period as the basis of gestational age assignment". Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology 1 (3): 212. doi:10.1046/j.1469-0705.1991.01030212.x. PMID 12797075. [1]

- ^ "Delaying your period with birth control pills". Mayo Clinic. http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/womens-health/WO00069. Retrieved September 20, 2011.

- ^ "How can I delay my period while on holiday?". National Health Service, United Kingdom. http://www.nhs.uk/chq/Pages/830.aspx?CategoryID=60&SubCategoryID=179. Retrieved September 20, 2011.

- ^ "Do you really need to have a period every month?". Discovery Health. http://health.howstuffworks.com/sexual-health/female-reproductive-system/monthly-period2.htm. Retrieved September 20, 2011.

- ^ Amy Lind, Stephanie Brzuzy (2007). Battleground: Women, Gender, and Sexuality: Volume 2: M-Z. Greenwood. pp. 348. ISBN 9780313340390.

- ^ Kam, Katherine. "Eliminate periods with birth control?". WebMD. http://www.webmd.com/sex/birth-control/features/no-more-periods. Retrieved September 20, 2011.

- ^ Clark-Flory, Tracy. "The end of menstruation". Salon. http://www.salon.com/life/feature/2008/02/04/menstruation. Retrieved September 20, 2011.

- ^ "Herbs For Premenstrual Syndrome". HerbalRemedies.com. 2004. http://www.herbalremediesinfo.com/premenstrualsyndrome.html. Retrieved 2006-08-08.

- ^ Strassmann BI (1996). "The evolution of endometrial cycles and menstruation". Q Rev Biol 71 (2): 181–220.

- ^ Kathleen O'Grady (2000). Is Menstruation Obsolete?. The Canadian Women's Health Network. http://www.cwhn.ca/resources/menstruation/obsolete.html. Retrieved 2007-01-21.

- ^ Desmond Morris (1997). The Human Sexes. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Chris Knight (1991). Blood relations: menstruation and the origins of culture. New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-06308-3.

- ^ Adams, Cecil (2002-12-20). "Does menstrual synchrony really exist?". The Straight Dope. The Chicago Reader. http://www.straightdope.com/columns/021220.html. Retrieved 2007-01-10.

- ^ Strassmann BI (1996). "The evolution of endometrial cycles and menstruation". Q Rev Biol 71 (2): 181–220.

Human physiology and endocrinology of sexual reproduction Menstrual and estrous cycle Gametogenesis Spermatogenesis (spermatogonium, spermatocyte, spermatid, sperm) · Oogenesis (oogonium, oocyte, ootid, ovum) · Germ cell (gonocyte, gamete)Human sexual behavior Sexual intercourse · Masturbation · Erection · Orgasm · Ejaculation · Insemination · Fertilisation/Fertility · Implantation · Pregnancy · Postpartum period · Mechanics of sexLife span Egg (biology) Reproductive endocrinology

and infertilityBreast Menstrual cycle Events and phases Life stages Tracking SignsSystemsSuppression Disorders Related events In culture and religion Categories:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.