- Colorectal cancer

-

Colorectal cancer Classification and external resources

Diagram of the lower gastrointestinal tractICD-10 C18-C20/C21 ICD-9 153.0-154.1 ICD-O: M8140/3 (95% of cases) OMIM 114500 DiseasesDB 2975 MedlinePlus 000262 eMedicine med/413 med/1994 ped/3037 Colorectal cancer, commonly known as bowel cancer, is a cancer caused by uncontrolled cell growth (neoplasia), in the colon, rectum, or vermiform appendix.[citation needed] Colorectal cancer is clinically distinct from anal cancer, which affects the anus.

Colorectal cancers start in the lining of the bowel. If left untreated, it can grow into the muscle layers underneath, and then through the bowel wall. Most begin as a small growth on the bowel wall: a colorectal polyp or adenoma. These mushroom-shaped growths are usually benign, but some develop into cancer over time. Localized bowel cancer is usually diagnosed through colonoscopy.

Invasive cancers that are confined within the wall of the colon (T stages I and II) are often curable with surgery, For example, in England over 90% of patients diagnosed at this stage will survive the disease beyond 5 years.[1] However, if left untreated, the cancer can spread to regional lymph nodes (stage III). In England, around 48% of patients diagnosed at this stage survive the disease beyond five years.[1] Cancer that has spread widely around the body (stage IV) is usually not curable; approximately 7% of patients in England diagnosed at this stage survive beyond five years.[1]

Colorectal cancer is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer in the world, but it is more common in developed countries.[2][broken citation] Around 60% of cases were diagnosed in the developed world.[3] GLOBOCAN estimated that, in 2008, 1.24 million new cases of colorectal cancer were clinically diagnosed, and that this type of cancer killed 610,000 people.[3]

Contents

Signs and symptoms

The symptoms of colorectal cancer depend on the location of tumor in the bowel, and whether it has spread elsewhere in the body (metastasis). While no symptom is diagnostic of colorectal cancer, rectal bleeding or anemia are high risk features.[4]

Local

Local symptoms are more likely if the tumor is located closer to the anus. There may be a change in bowel habit (such as unusual and unexplained constipation or diarrhea), and a feeling of incomplete defecation (rectal tenesmus). Lower gastrointestinal bleeding, including the passage of bright red blood in the stool, may indicate colorectal cancer, as may the increased presence of mucus. Melena, black stool with a tarry appearance, normally occurs in upper gastrointestinal bleeding (such as from a duodenal ulcer), but is sometimes encountered in colorectal cancer when the disease is located in the beginning of the large bowel.

A tumor that is large enough to fill the entire lumen of the bowel may cause bowel obstruction. This situation is characterized by constipation, abdominal pain, abdominal distension and vomiting. This occasionally leads to the obstructed and distended bowel perforating and causing peritonitis. A large left colonic tumor may compress the left ureter and cause hydronephrosis.

Certain local effects of colorectal cancer occur when the disease has become more advanced. A large tumor is more likely to be noticed on feeling the abdomen, and it may be noticed by a doctor on physical examination. The disease may invade other organs, and may cause blood or air in the urine (invasion of the bladder) or vaginal discharge (invasion of the female reproductive tract).

Constitutional

If a tumor has caused chronic bleeding in the bowel, iron deficiency anemia may occur, causing a range of symptoms that may include fatigue, palpitations and pale skin (pallor). Colorectal cancer may also lead to weight loss, generally due to a decreased appetite[citation needed].

There may be rarer symptoms including unexplained fever or thrombosis, usually deep vein thrombosis. Such symptoms, known as paraneoplastic syndrome, are due to the body's immune response to the cancer, rather than the tumor itself.

Risk factors

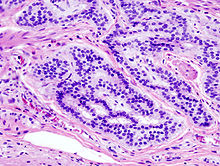

Micrograph of a tubular adenoma (left of image), a type of colonic polyp and a precursor of colorectal cancer. Normal colorectal mucosa is seen on the right. H&E stain.

Micrograph of a tubular adenoma (left of image), a type of colonic polyp and a precursor of colorectal cancer. Normal colorectal mucosa is seen on the right. H&E stain.

The lifetime risk of developing colon cancer in the United States is about 7%. Certain factors increase a person's risk of developing the disease.[5] These include:

- Age: The risk of developing colorectal cancer increases with age. Most cases occur in the 60s and 70s, while cases before age 50 are uncommon unless a family history of early colon cancer is present.[6]

- Polyps of the colon, particularly adenomatous polyps, are a risk factor for colon cancer. The removal of colon polyps at the time of colonoscopy reduces the subsequent risk of colon cancer. Larger and those with greater surface area (villous polyps compared to tubular) are more likely to undergo neoplasia due to the greater likelyhood of one of these cells undergoing the series of malignant transformations into cancer.

- History of cancer. Individuals who have previously been diagnosed and treated for colon cancer are at risk for developing colon cancer in the future. Women who have had cancer of the ovary, uterus, or breast are at higher risk of developing colorectal cancer.

- Heredity:

- Family history of colon cancer, especially in a close relative before the age of 55 or multiple relatives.[7]

- Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) carries a near 100% risk of developing colorectal cancer by the age of 40 if untreated

- Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) or Lynch syndrome

- Gardner syndrome

- Smoking: Smokers are more likely to die of colorectal cancer than nonsmokers. An American Cancer Society study found "Women who smoked were more than 40% more likely to die from colorectal cancer than women who never had smoked. Male smokers had more than a 30% increase in risk of dying from the disease compared to men who never had smoked."[8][9]

- Diet: Studies show that a diet high in red meat[10] and low in fresh fruit, vegetables, poultry and fish increases the risk of colorectal cancer. In June 2005, a study by the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition suggested that diets high in red and processed meat, as well as those low in fiber, are associated with an increased risk of colorectal cancer. Individuals who frequently eat fish showed a decreased risk.[11] However, other studies have cast doubt on the claim that diets high in fiber decrease the risk of colorectal cancer; rather, low-fiber diet was associated with other risk factors, leading to confounding.[12] The nature of the relationship between dietary fiber and risk of colorectal cancer remains controversial.

- Lithocholic acid: Lithocholic acid is a bile acid that acts as a detergent to solubilize fats for absorption. It is made from chenodeoxycholic acid by bacterial action in the colon. It has been implicated in human and experimental animal carcinogenesis.[13] Carbonic acid type surfactants easily combine with calcium ion and become detoxication products.

- Physical inactivity: People who are physically active are at lower risk of developing colorectal cancer.

- Viruses: Exposure to some viruses (such as particular strains of human papilloma virus) may be associated with colorectal cancer.[citation needed]

- Primary sclerosing cholangitis offers a risk independent to ulcerative colitis.

- Low levels of selenium[14][15]

- Inflammatory bowel disease:[16][17] About one percent of colorectal cancer patients have a history of chronic ulcerative colitis. The risk of developing colorectal cancer varies inversely with the age of onset of the colitis and directly with the extent of colonic involvement and the duration of active disease. Patients with colorectal Crohn's disease have a more than average risk of colorectal cancer, but less than that of patients with ulcerative colitis.[18]

- Environmental factors.[16] Industrialized countries are at a relatively increased risk compared to less developed countries that traditionally had high-fiber/low-fat diets. Studies of migrant populations have revealed a role for environmental factors, particularly dietary, in the etiology of colorectal cancers.

- Exogenous hormones. The differences in the time trends in colorectal cancer in males and females could be explained by cohort effects in exposure to some gender-specific risk factor; one possibility that has been suggested is exposure to estrogens.[19] There is, however, little evidence of an influence of endogenous hormones on the risk of colorectal cancer. In contrast, there is evidence that exogenous estrogens such as hormone replacement therapy (HRT), tamoxifen, or oral contraceptives might be associated with colorectal tumors.[20]

- Alcohol: Drinking, especially heavily, may be a risk factor.[21]

- Vitamin B6 intake lowers the risk of colorectal cancer.[22]

Alcohol

The WCRF panel report Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity and the Prevention of Cancer: a Global Perspective finds the evidence "convincing" that alcoholic drinks increase the risk of colorectal cancer in men.[23]

The NIAAA reports that: "Epidemiologic studies have found a small but consistent dose-dependent association between alcohol consumption and colorectal cancer[24][25] even when controlling for fiber and other dietary factors.[26][27] Despite the large number of studies, however, causality cannot be determined from the available data."[21]

"Heavy alcohol use may also increase the risk of colorectal cancer" (NCI). One study found that "People who drink more than 30 grams of alcohol per day (and especially those who drink more than 45 grams per day) appear to have a slightly higher risk for colorectal cancer."[28] Another found that "The consumption of one or more alcoholic beverages a day at baseline was associated with approximately a 70% greater risk of colon cancer."[28][29][30]

One study found "While there was a more than twofold increased risk of significant colorectal neoplasia in people who drink spirits and beer, people who drank wine had a lower risk. In our sample, people who drank more than eight servings of beer or spirits per week had at least a one in five chance of having significant colorectal neoplasia detected by screening colonoscopy.".[31]

Other research suggests "to minimize your risk of developing colorectal cancer, it's best to drink in moderation."[21]

On its colorectal cancer page, the National Cancer Institute does not list alcohol as a risk factor;[32] however, on another page it states, "Heavy alcohol use may also increase the risk of colorectal cancer".[33]

Drinking may be a cause of earlier onset of colorectal cancer.[34]

Pathogenesis

Colorectal cancer is a disease originating from the epithelial cells lining the colon or rectum of the gastrointestinal tract, most frequently as a result of mutations in the Wnt signaling pathway that artificially increase signaling activity. The mutations can be inherited or are acquired, and must probably occur in the intestinal crypt stem cell.[35][36] The most commonly mutated gene in all colorectal cancer is the APC gene, which produces the APC protein. The APC protein is a "brake" on the accumulation of β-catenin protein; without APC, β-catenin accumulates to high levels and translocates (moves) into the nucleus, binds to DNA, and activates the transcription of genes that are normally important for stem cell renewal and differentiation but when inappropriately expressed at high levels can cause cancer. While APC is mutated in most colon cancers, some cancers have increased β-catenin because of mutations in β-catenin (CTNNB1) that block its degradation, or they have mutation(s) in other genes with function analogous to APC such as AXIN1, AXIN2, TCF7L2, or NKD1.[37]

Beyond the defects in the Wnt-APC-beta-catenin signaling pathway, other mutations must occur for the cell to become cancerous. The p53 protein, produced by the TP53 gene, normally monitors cell division and kills cells if they have Wnt pathway defects. Eventually, a cell line acquires a mutation in the TP53 gene and transforms the tissue from an adenoma into an invasive carcinoma. (Sometimes the gene encoding p53 is not mutated, but another protective protein named BAX is.)[37]

Other apoptotic proteins commonly deactivated in colorectal cancers are TGF-β and DCC (Deleted in Colorectal Cancer). TGF-β has a deactivating mutation in at least half of colorectal cancers. Sometimes TGF-β is not deactivated, but a downstream protein named SMAD is.[37] DCC commonly has deletion of its chromosome segment in colorectal cancer.[38]

Some genes are oncogenes - they are overexpressed in colorectal cancer. For example, genes encoding the proteins KRAS, RAF,[disambiguation needed

] and PI3K, which normally stimulate the cell to divide in response to growth factors, can acquire mutations that result in over-activation of cell proliferation. The chronological order of mutations is sometimes important, with a primary KRAS mutation generally leading to a self-limiting hyperplastic or borderline lesion, but if occurring after a previous APC mutation it often progresses to cancer.[39] PTEN, a tumor suppressor, normally inhibits PI3K, but can sometimes become mutated and deactivated.[37]

] and PI3K, which normally stimulate the cell to divide in response to growth factors, can acquire mutations that result in over-activation of cell proliferation. The chronological order of mutations is sometimes important, with a primary KRAS mutation generally leading to a self-limiting hyperplastic or borderline lesion, but if occurring after a previous APC mutation it often progresses to cancer.[39] PTEN, a tumor suppressor, normally inhibits PI3K, but can sometimes become mutated and deactivated.[37]Diagnosis

Endoscopic image of colon cancer identified in sigmoid colon on screening colonoscopy in the setting of Crohn's disease.

Endoscopic image of colon cancer identified in sigmoid colon on screening colonoscopy in the setting of Crohn's disease.

Colorectal cancer can take many years to develop and early detection of colorectal cancer greatly improves the chances of a cure. The National Cancer Policy Board of the Institute of Medicine estimated in 2003 that even modest efforts to implement colorectal cancer screening methods would result in a 29 percent drop in cancer deaths in 20 years. Despite this, colorectal cancer screening rates remain low.[40] Therefore, screening for the disease is recommended in individuals who are at increased risk. There are several different tests available for this purpose.

- Digital rectal exam (DRE): The doctor inserts a lubricated, gloved finger into the rectum to feel for abnormal areas. It only detects tumors large enough to be felt in the distal part of the rectum but is useful as an initial screening test.

- Fecal occult blood test (FOBT): a test for blood in the stool. Two types of tests can be used for detecting occult blood in stools i.e. guaiac based (chemical test) and immunochemical. The sensitivity of immunochemical testing is superior to that of chemical testing without an unacceptable reduction in specifity.[41]

- M2-PK: a CE marked stool test which indicates colorectal polyps, colorectal cancer, acute and chronic inflammatory bowel disease and other diseases of the digestive tract. The test result is not affected by any foods, so no dietary restrictions are necessary before taking the stool sample. It detects bleeding and non-bleeding colorectal polyps and tumors and has significantly superior sensitivity compared to conventional occult blood tests.[42] The amount of M2-PK in stool can be quantified in 4 mg of feces either by ELISA or with a Point-of-Care Rapid Test.

- Endoscopy:

- Sigmoidoscopy: A lighted probe (sigmoidoscope) is inserted into the rectum and lower colon to check for polyps and other abnormalities.

- Colonoscopy: A lighted probe called a colonoscope is inserted into the rectum and the entire colon to look for polyps and other abnormalities that may be caused by cancer. A colonoscopy has the advantage that if polyps are found during the procedure they can be removed immediately. Tissue can also be taken for biopsy.

In the United States, colonoscopy or FOBT plus sigmoidoscopy are the preferred screening options.

Other screening methods

- Double contrast barium enema (DCBE): First, an overnight preparation is taken to cleanse the colon. An enema containing barium sulfate is administered, then air is insufflated into the colon, distending it. The result is a thin layer of barium over the inner lining of the colon which is visible on X-ray films. A cancer or a precancerous polyp can be detected this way. This technique can miss the (less common) flat polyp.

- Virtual colonoscopy replaces X-ray films in the double contrast barium enema (above) with a special computed tomography scan and requires special workstation software in order for the radiologist to interpret. This technique is approaching colonoscopy in sensitivity for polyps. However, any polyps found must still be removed by standard colonoscopy.

- Standard computed axial tomography is an x-ray method that can be used to determine the degree of spread of cancer, but is not sensitive enough to use for screening. Some cancers are found in CAT scans performed for other reasons.

- Blood tests: Measurement of the patient's blood for elevated levels of certain proteins can give an indication of tumor load. In particular, high levels of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) in the blood can indicate metastasis of adenocarcinoma. These tests are frequently false positive or false negative, and are not recommended for screening, it can be useful to assess disease recurrence. CA19-9 and CA 242 biomarkers can indicate e-selectin related metastatic risks, help follow therapeutic progress, and assess disease recurrence. Also the level of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases 1 (TIMP1) in the blood has been shown to correlate with the occurrence of colon cancer. A TIMP1 test can be helpful in an evaluation to assess the risk of having developed colorectal cancer. TIMP1 is particularly helpful as a marker for early identification of colorectal cancer, where it has been shown to have a high specificity and sensitivity.[43] The research of TIMP1, as a marker for early identification of colorectal cancer, is particularly focused in Denmark as a collaboration between the University of Copenhagen, the Technical University of Denmark, Rigshospitalet and Cancer Marker A/S, which is a Danish medico-company.

- Cell free DNA - Blood: There is extensive literature describing DNA shed from tumors circulating as cell free DNA in the blood.[44] Using highly sensitive assays, studies report the presence of DNA mutations [45] and DNA methylation tumor markers such as SEPT9 in the plasma of colon cancer patients.[46][47] In Europe, the SEPT9 methylation marker has been developed into the CE marked Epi proColon test (Epigenomics AG) and the ms9 test (Abbott Molecular). It is also the subject of a clinical trial[48] in the US, and has been licensed for the development of LDT tests by Quest Diagnostics and ARUP Laboratories in the US, and Warnex Laboratories [49] in Canada.[50]

- Genetic counseling and genetic testing for families who may have a hereditary form of colon cancer, such as hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) or familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP).

- Positron emission tomography (PET) is a 3-dimensional scanning technology where a radioactive sugar is injected into the patient, the sugar collects in tissues with high metabolic activity, and an image is formed by measuring the emission of radiation from the sugar. Because cancer cells often have very high metabolic rates, this can be used to differentiate benign and malignant tumors. PET is not used for screening and does not (yet) have a place in routine workup of colorectal cancer cases.

- Whole-body PET imaging is the most accurate diagnostic test for detection of recurrent colorectal cancer, and is a cost-effective way to differentiate resectable from nonresectable disease. A PET scan is indicated whenever a major management decision depends upon accurate evaluation of tumour presence and extent.

- Stool DNA testing is an emerging technology in screening for colorectal cancer. Premalignant adenomas and cancers shed DNA markers from their cells which are not degraded during the digestive process and remain stable in the stool. Capture, followed by PCR amplifies the DNA to detectable levels for assay. Clinical studies have shown a cancer detection sensitivity of 71%–91%.[51]

- High C-Reactive Protein levels is risk marker.[52]

- miRNA-profiling-based screening for detection of early-stage colorectal cancer: The life science and research company Exiqon A/S has developed a novel plasma miRNA screening assay for identifying early-stage colorectal cancer. Plasma miRNA has been shown to be a promising biomarker for many diseases including cancer. The goal of this technique is to select individuals for colonoscopy rather than to replace colonoscopy as the gold standard of colorectal cancer diagnosis. Blood plasma samples collected from patients with early, resectable (Stage II) colorectal cancer and sex-and age-matched healthy volunteers were profiled. So far potential biomarkers have shown promising specificity and sensitivity. The same technology can also be applied to patients who may be at higher risk of relapse and therefore in need for more aggressive adjuvant chemotherapy.[53][54][55]

Monitoring

Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) is a protein found on virtually all colorectal tumors. CEA may be used to monitor and assess response to treatment in patients with metastatic disease. CEA can also be used to monitor recurrence in patients post-operatively.[citation needed]

Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinases 1 (TIMP1) is also possible to be used as a monitor and assess response to treatment of coloreactal cancer. Particular when it is combined with (CEA).[43] Constantly increased levels of TIMP1 during treatment identify patients with a very poor prognosis.[56]

M2-PK EDTA- Plasma Test. M2-PK may be used to monitor and assess response to treatment of colorectal cancer.

Pathology

Gross appearance of a colectomy specimen containing two adenomatous polyps (the brownish oval tumors above the labels, attached to the normal beige lining by a stalk) and one invasive colorectal carcinoma (the crater-like, reddish, irregularly shaped tumor located above the label).

Gross appearance of a colectomy specimen containing two adenomatous polyps (the brownish oval tumors above the labels, attached to the normal beige lining by a stalk) and one invasive colorectal carcinoma (the crater-like, reddish, irregularly shaped tumor located above the label).

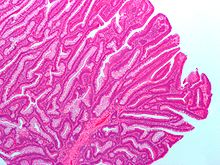

Micrograph of an invasive adenocarcinoma (the most common type of colorectal cancer). The cancerous cells are seen in the center and at the bottom right of the image (blue). Near normal colon-lining cells are seen at the top right of the image.

Micrograph of an invasive adenocarcinoma (the most common type of colorectal cancer). The cancerous cells are seen in the center and at the bottom right of the image (blue). Near normal colon-lining cells are seen at the top right of the image.

The pathology of the tumor is usually reported from the analysis of tissue taken from a biopsy or surgery. A pathology report will usually contain a description of cell type and grade. The most common colon cancer cell type is adenocarcinoma which accounts for 95% of cases. Other, rarer types include lymphoma and squamous cell carcinoma.

Cancers on the right side (ascending colon and cecum) tend to be exophytic, that is, the tumour grows outwards from one location in the bowel wall. This very rarely causes obstruction of feces, and presents with symptoms such as anemia. Left-sided tumours tend to be circumferential, and can obstruct the bowel much like a napkin ring.

Adenocarcinoma is a malignant epithelial tumor, originating from glandular epithelium of the colorectal mucosa. It invades the wall, infiltrating the muscularis mucosae, the submucosa and thence the muscularis propria. Tumor cells describe irregular tubular structures, harboring pluristratification, multiple lumens, reduced stroma ("back to back" aspect). Sometimes, tumor cells are discohesive and secrete mucus, which invades the interstitium producing large pools of mucus/colloid (optically "empty" spaces) - mucinous (colloid) adenocarcinoma, poorly differentiated. If the mucus remains inside the tumor cell, it pushes the nucleus at the periphery - "signet-ring cell." Depending on glandular architecture, cellular pleomorphism, and mucosecretion of the predominant pattern, adenocarcinoma may present three degrees of differentiation: well, moderately, and poorly differentiated.[57]

Most colorectal cancer tumors are thought to be cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) positive. This enzyme is generally not found in healthy colon tissue, but is thought to fuel abnormal cell growth.

Staging

Colon cancer staging is an estimate of the amount of penetration of a particular cancer. It is performed for diagnostic and research purposes, and to determine the best method of treatment. The systems for staging colorectal cancers depend on the extent of local invasion, the degree of lymph node involvement and whether there is distant metastasis.

Definitive staging can only be done after surgery has been performed and pathology reports reviewed. An exception to this principle would be after a colonoscopic polypectomy of a malignant pedunculated polyp with minimal invasion. Preoperative staging of rectal cancers may be done with endoscopic ultrasound. Adjunct staging of metastasis include Abdominal Ultrasound, MRI, CT, PET Scanning, and other imaging studies.

The most common staging system is the TNM (for tumors/nodes/metastases) system, from the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC). The TNM system assigns a number based on three categories. "T" denotes the degree of invasion of the intestinal wall, "N" the degree of lymphatic node involvement, and "M" the degree of metastasis. The broader stage of a cancer is usually quoted as a number I, II, III, IV derived from the TNM value grouped by prognosis; a higher number indicates a more advanced cancer and likely a worse outcome. Details of this system are in the graph below:

AJCC stage TNM stage 2002 6th edition TNM stage criteria for colorectal cancer (superceded by 2010 7th edition)[58] Stage 0 Tis N0 M0 Tis: Tumor confined to mucosa; cancer-in-situ Stage I T1 N0 M0 T1: Tumor invades submucosa Stage I T2 N0 M0 T2: Tumor invades muscularis propria Stage II-A T3 N0 M0 T3: Tumor invades subserosa or beyond (without other organs involved) Stage II-B T4 N0 M0 T4: Tumor invades adjacent organs or perforates the visceral peritoneum Stage III-A T1-2 N1 M0 N1: Metastasis to 1 to 3 regional lymph nodes. T1 or T2. Stage III-B T3-4 N1 M0 N1: Metastasis to 1 to 3 regional lymph nodes. T3 or T4. Stage III-C any T, N2 M0 N2: Metastasis to 4 or more regional lymph nodes. Any T. Stage IV any T, any N, M1 M1: Distant metastases present. Any T, any N. Dukes system

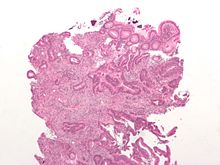

Micrograph of a colorectal adenocarcinoma metastasis to a lymph node. The cancerous cells are at the top center-left of the image, in glands (circular/ovoid structures) and eosinophilic (bright pink). H&E stain.

Micrograph of a colorectal adenocarcinoma metastasis to a lymph node. The cancerous cells are at the top center-left of the image, in glands (circular/ovoid structures) and eosinophilic (bright pink). H&E stain.

The Dukes classification is an older and less complicated staging system, that predates the TNM system. It identified the stages as:[59]

- A - Tumour confined to the intestinal wall

- B - Tumour invading through the intestinal wall

- C - With lymph node(s) involvement (this is further subdivided into C1 lymph node involvement where the apical node is not involved and C2 where the apical lymph node is involved)

- D - With distant metastasis

Astler-Coller

A: Tumor limited to mucosa; carcinoma in situ B1: Tumor grows through muscularis mucosae but not through muscularis propria B2: Tumor grows beyond muscularis propria C1: Stage B1 with regional lymph node metastases C2: Stage B2 with regional lymph node metastases D: Distant metastases.

Additional Staging

venous invasion (v)

- v0 no venous invasion

- v1 microscopic venous invasion

- v2 macroscopic venous invasion

lymphatic invasion (l)

- l0 no lymphatic vessel invasion

- l1 lymphatic vessel invasion

histologic grade (G)

- g1 well differentiated

- g2 moderately differentiated

- g3 poorly differentiated

- g4 undiffererentiated

Prevention

Most colorectal cancers should be preventable, through increased surveillance, improved lifestyle, and, probably, the use of dietary chemopreventative agents.

Surveillance

Most colorectal cancers arise from adenomatous polyps. These lesions can be detected and removed during colonoscopy. A 1993 study suggested this procedure would decrease by > 80% the risk of cancer death, provided it is started by the age of 50, and repeated every 5 or 10 years.[60] A 2009 study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine[61] implies that colonoscopy screening prevents approximately two thirds of the deaths due to colorectal cancers on the left side of the colon, and is not associated with a significant reduction in deaths from right-sided disease.[62] The summary result suggested approximately a 37% reduction in net death rate from colorectal cancer.

As per current guidelines under National Comprehensive Cancer Network, in average risk individuals with negative family history of colon cancer and personal history negative for adenomas or inflammatory bowel diseases, flexible sigmoidoscopy every 5 years with fecal occult blood testing annually or double contrast barium enema are other options acceptable for screening rather than colonoscopy every 10 years (which is currently the "gold standard" of care).

Lifestyle and nutrition

The comparison of colorectal cancer incidence in various countries strongly suggests that sedentarity, overeating (i.e., high caloric intake), and perhaps a diet high in meat (red or processed) could increase the risk of colorectal cancer. In contrast, a healthy body weight, physical fitness, and good nutrition decreases cancer risk in general. Accordingly, lifestyle changes could decrease the risk of colorectal cancer as much as 60-80%.[63]

A high intake of dietary fiber (from eating fruits, vegetables, cereals, and other high fiber food products) has, until recently, been thought to reduce the risk of colorectal cancer and adenoma. In the largest study ever to examine this theory (88,757 subjects tracked over 16 years), it has been found that a fiber rich diet does not reduce the risk of colon cancer.[64] A 2005 meta-analysis study further supports these findings.[65]

The Harvard School of Public Health states: "Health Effects of Eating Fiber: Long heralded as part of a healthy diet, fiber appears to reduce the risk of developing various conditions, including heart disease, diabetes, diverticular disease, and constipation. Despite what many people may think, however, fiber probably has little, if any effect on colon cancer risk."[66]

Physical Activity

Physical inactivity is a risk factor for developing colorectal cancer. The American Institute for Cancer Research (AICR) classifies the evidence for the role of physical activity in reducing the risk of developing colorectal cancer as “convincing.” [23] The report goes on to recommend that people be physically active everyday and strive for attaining at least 30 minutes of physical activity with a recommendation of 30-60 minutes of moderate to vigorous activity daily.

The evidence supporting physical activity as prevention for colorectal cancer is deemed “surprisingly consistent” by the AICR. A meta-analysis of 19 cohort studies published in 2004 showed a statistically significant reduction in risk for physical activity and colon cancer. This effect was not seen for rectal cancer. [67]

Chemoprevention

More than 200 agents, including the above cited phytochemicals, and other food components like calcium or folic acid (a B vitamin), and NSAIDs like aspirin, are able to decrease carcinogenesis in pre-clinical development models: Some studies show full inhibition of carcinogen-induced tumours in the colon of rats. Other studies show strong inhibition of spontaneous intestinal polyps in mutated mice (Min mice). Chemoprevention clinical trials in human volunteers have shown smaller prevention, but few intervention studies have been completed today. The "chemoprevention database" shows the results of all published scientific studies of chemopreventive agents, in people and in animals.[68]

Aspirin chemoprophylaxis

Aspirin should not be taken routinely to prevent colorectal cancer, even in people with a family history of the disease, because the risk of bleeding and kidney failure from high dose aspirin (300 mg or more) outweigh the possible benefits.[69]

A clinical practice guideline of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommended against taking aspirin (grade D recommendation).[70] The Task Force acknowledged that aspirin may reduce the incidence of colorectal cancer, but "concluded that harms outweigh the benefits of aspirin and NSAID use for the prevention of colorectal cancer". A subsequent meta-analysis concluded "300 mg or more of aspirin a day for about 5 years is effective in primary prevention of colorectal cancer in randomised controlled trials, with a latency of about 10 years".[71] However, long-term doses over 81 mg per day may increase bleeding events.[72]

Calcium

The meta-analysis by the Cochrane Collaboration of randomized controlled trials published through 2002 concluded "Although the evidence from two RCTs suggests that calcium supplementation might contribute to a moderate degree to the prevention of colorectal adenomatous polyps, this does not constitute sufficient evidence to recommend the general use of calcium supplements to prevent colorectal cancer."[73] Subsequently, one randomized controlled trial by the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) reported negative results.[74] A second randomized controlled trial reported reduction in all cancers, but had insufficient colorectal cancers for analysis.[75]

Vitamin D

A scientific review undertaken by the National Cancer Institute found that vitamin D was beneficial in preventing colorectal cancer, which showed an inverse relationship with blood levels of 80 nmol/L or higher associated with a 72% risk reduction compared with lower than 50 nmol/L.[76] A possible mechanism is inhibition of Hedgehog signal transduction.[77]

Management

The treatment depends on the stage of the cancer. When colorectal cancer is caught at early stages (with little spread), it can be curable. However, when it is detected at later stages (when distant metastases are present), it is less likely to be curable.

Surgery remains the primary treatment, while chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy may be recommended depending on the individual patient's staging and other medical factors.

Because colon cancer primarily affects the elderly, it can be a challenge to determine how aggressively to treat a particular patient, especially after surgery. Clinical trials suggest "otherwise fit" elderly patients fare well if they have adjuvant chemotherapy after surgery, so chronological age alone should not be a contraindication to aggressive management.[78]

Surgery

Surgeries can be categorised into curative, palliative, bypass, fecal diversion, or open-and-close.

Curative surgical treatment can be offered if the tumor is localized.

- Very early cancer that develops within a polyp can often be cured by removing the polyp (i.e., polypectomy) at the time of colonoscopy.

- In colon cancer, a more advanced tumor typically requires surgical removal of the section of colon containing the tumor with sufficient margins, and radical en-bloc resection of mesentery and lymph nodes to reduce local recurrence (i.e., colectomy). If possible, the remaining parts of colon are anastomosed to create a functioning colon. In cases when anastomosis is not possible, a stoma (artificial orifice) is created.

- Curative surgery on rectal cancer includes total mesorectal excision (lower anterior resection) or abdominoperineal excision.

In case of multiple metastases, palliative (noncurative) resection of the primary tumor is still offered to reduce further morbidity caused by tumor bleeding, invasion, and its catabolic effect. Surgical removal of isolated liver metastases is, however, common and may be curative in selected patients; improved chemotherapy has increased the number of patients who are offered surgical removal of isolated liver metastases.

If the tumor invaded into adjacent vital structures, which makes excision technically difficult, the surgeons may prefer to bypass the tumor (ileotransverse bypass) or to do a proximal fecal diversion through a stoma.

Laparoscopic-assisted colectomy is a minimally invasive technique that can reduce the size of the incision and may reduce postoperative pain.

As with any surgical procedure, colorectal surgery may result in complications, including

- wound infection, dehiscence (bursting of wound) or hernia,

- anastomosis breakdown, leading to abscess or fistula formation, and/or peritonitis,

- bleeding with or without hematoma formation,

- adhesions resulting in bowel obstruction. A 5-year study of patients who had surgery in 1997 found the risk of hospital readmission to be 15% after panproctocolectomy, 9% after total colectomy, and 11% after ileostomy[79]

- adjacent organ injury; most commonly to the small intestine, ureters, spleen, or bladder.

- cardiorespiratory complications, such as myocardial infarction, pneumonia, arrythmia, pulmonary embolism, etc.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is used to reduce the likelihood of metastasis developing, shrink tumor size, or slow tumor growth. Chemotherapy is often applied after surgery (adjuvant), before surgery (neoadjuvant), or as the primary therapy (palliative). The treatments listed here have been shown in clinical trials to improve survival and/or reduce mortality rate, and have been approved for use by the US Food and Drug Administration. In colon cancer, chemotherapy after surgery is usually only given if the cancer has spread to the lymph nodes(Stage III).

- Adjuvant (after surgery) chemotherapy

- 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) or capecitabine (Xeloda)

- Leucovorin (LV, folinic Acid)

- Oxaliplatin (Eloxatin)

- Chemotherapy for metastatic disease. Commonly used first line chemotherapy regimens involve the combination of infusional 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) with bevacizumab or infusional 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan (FOLFIRI) with bevacizumab or the same chemotherapy drug combinations with cetuximab in KRAS wild type tumors

- 5-fluorouracil (5-FU)

- capecitabine (Xeloda)

- UFT or Tegafur-uracil

- Leucovorin (LV, folinic Acid)

- Irinotecan (Camptosar)

- Oxaliplatin (Eloxatin)

- Gemcitabine (Gemzar)

- Bevacizumab (Avastin)

- Cetuximab (Erbitux)

- Panitumumab (Vectibix)

- In clinical trials for treated/untreated metastatic disease.[80]

- Bortezomib (Velcade)

- Oblimersen (Genasense, G3139)

- Gefitinib and erlotinib (Tarceva)

- Topotecan (Hycamtin)

At the 2008 annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, researchers announced that colorectal cancer patients that have a mutation in the KRAS gene do not respond to certain therapies, those that inhibit the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)--namely Erbitux (cetuximab) and Vectibix (panitumumab).[81] Following recommendations by ASCO, patients should now be tested for the KRAS gene mutation before being offered these EGFR-inhibiting drugs.[82] In July 2009, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) updated the labels of two anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody drugs (panitumumab (Vectibix) and cetuximab (Erbitux)) indicated for treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer to include information about KRAS mutations.[83]

However, having the normal KRAS version does not guarantee these drugs will benefit the patient.[81]

“The trouble with the KRAS mutation is that it’s downstream of EGFR,” says Richard Goldberg, MD, director of oncology at the Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of North Carolina. “It doesn’t matter if you plug the socket if there’s a short downstream of the plug. The mutation turns [EGFR] into a switch that’s always on.” But this doesn’t mean that having normal, or wild-type, KRAS is a fail-safe. “It isn’t foolproof,” cautions Goldberg. “If you have wild-type KRAS, you’re more likely to respond, but it’s not a guarantee.” Tumors shrink in response to these drugs in up to 40 percent of patients with wild-type KRAS, and progression-free and overall survival is increased.

The cost benefit of testing patients for the KRAS gene could potentially save about $740 million a year by not providing EGFR-inhibiting drugs to patients who would not benefit from the drugs. "With the assumption that patients with mutated Kras (35.6% of all patients) would not receive cetuximab (other studies have found Kras mutation in up to 46% of patients), theoretical drug cost savings would be $753 million; considering the cost of Kras testing, net savings would be $740 million."[84]

Radiation therapy

Radiotherapy is not used routinely in colon cancer, as normal cells in the bowel lining are also rapidly reproducing and can thus have their vitality and reproduction affected by the radiation just as the cancer cells are, a condition called radiation enteritis.[85] It is also difficult to target specific portions of the colon. It is more common for radiation to be used in rectal cancer, since the rectum does not move as much as the colon and is thus easier to target. Indications include:

- Colon cancer

- pain relief and palliation - targeted at metastatic tumor deposits if they compress vital structures and/or cause pain

- Rectal cancer

- neoadjuvant - given before surgery in patients with tumors that extend outside the rectum or have spread to regional lymph nodes, to decrease the risk of recurrence following surgery or to allow for less invasive surgical approaches (such as a low anterior resection instead of an abdominoperineal resection). In locally advanced adenocarcinoma of middle and lower rectum, regional hyperthermia added to chemoradiotherapy achieved good results in terms of rate of sphincter-sparing surgery.[86]

-

- adjuvant - where a tumor perforates the rectum or involves regional lymph nodes (AJCC T3 or T4 tumors or Duke's B or C tumors)

- palliative - to decrease the tumor burden to relieve or prevent symptoms

Sometimes chemotherapy agents are used to increase the effectiveness of radiation by sensitizing tumor cells, if present.

Immunotherapy

Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) is being investigated as an adjuvant mixed with autologous tumor cells in immunotherapy for colorectal cancer.[87]

Cancer Vaccine

TroVax, a cancer vaccine,[88] produced by Oxford BioMedica,[89] is in Phase III trials for renal cancers, and Phase III trials are planned for colon cancers.[90]

Treatment of liver metastases

According to the American Cancer Society statistics in 2006,[91] over 20% of patients present with metastatic (stage IV) colorectal cancer at the time of diagnosis, and up to 25% of this group will have isolated liver metastasis that is potentially resectable. Lesions which undergo curative resection have demonstrated 5-year survival outcomes now exceeding 50%.[92]

Resectability of a liver metastasis is determined using preoperative imaging studies (CT or MRI), intraoperative ultrasound, and by direct palpation and visualization during resection. Lesions confined to the right lobe are amenable to en bloc removal with a right hepatectomy (liver resection) surgery. Smaller lesions of the central or left liver lobe may sometimes be resected in anatomic "segments", while large lesions of left hepatic lobe are resected by a procedure called hepatic trisegmentectomy. Treatment of lesions by smaller, nonanatomic "wedge" resections is associated with higher recurrence rates. Some lesions which are not initially amenable to surgical resection may become candidates if they have significant responses to preoperative chemotherapy or immunotherapy regimens. Lesions which are not amenable to surgical resection for cure can be treated with modalities including radio-frequency ablation (RFA), cryoablation, and chemoembolization.

Patients with colon cancer and metastatic disease to the liver may be treated in either a single surgery or in staged surgeries (with the colon tumor traditionally removed first) depending upon the fitness of the patient for prolonged surgery, the difficulty expected with the procedure with either the colon or liver resection, and the comfort of the surgery performing potentially complex hepatic surgery.

Aspirin

A study published in 2009 found that aspirin reduces risk of colorectal neoplasia in randomized trials, and inhibits tumor growth and metastases in animal models. The influence of aspirin on survival after diagnosis of colorectal cancer is unknown.[93] Several reports, including a prospective cohort of 1,279 people diagnosed with stages I-III (nonmetastatic) colorectal cancer,[94] have suggested a significant improvement in cancer-specific survival in a subset of patients using aspirin.[95]

Cimetidine

Cimetidine is being investigated in Japan as an adjuvant for adenocarcinomas,[96] including for stage III[97] and stage IV[98] colorectal cancers biomarked with overexpressed sialyl Lewis X and A epitopes. Multiple small trials suggest a significant survival improvement in the subset of patients with the sLeX and sLeA biomarkers that take cimetidine treatment perioperatively, through several mechanisms [2].

Support therapies

Cancer diagnosis very often results in an enormous change in the patient's psychological well-being. Various support resources are available from hospitals and other agencies, which provide counseling, social service support, cancer support groups, and other services. These services help to mitigate some of the difficulties of integrating patients' medical complications into other parts of their lives.

Palliative care

In patients with incurable colorectal cancer, palliative care can be considered for improving the patients symptom management and quality of life. Surgical options for treatment of symptoms include non-curative surgical resection of tumor, fecal diversion, and endoluminal laser surgery or stent placement. These procedures can be considered to alleviate symptoms and complications such as anemia from bleeding from the tumor, abdominal pain and intestinal obstruction.[99] Non-operative methods of symptomatic treatment include external beam or intraoperative radiation therapy for managing pain and tumor size as well as analgesic medications, including intrathetcal pain medication when necessary.[100]

Prognosis

Survival is directly related to detection and the type of cancer involved, but overall is poor for symptomatic cancers, as they are typically quite advanced. Survival rates for early stage detection is about 5 times that of late stage cancers. For example, patients with a tumor that has not breached the muscularis mucosa (TNM stage Tis, N0, M0) have an average 5-year survival of 100%, while those with an invasive cancer, i.e. T1 (within the submucosal layer) or T2 (within the muscular layer) cancer have an average 5-year survival of approximately 90%. Those with a more invasive tumor, yet without node involvement (T3-4, N0, M0) have an average 5-year survival of approximately 70%. Patients with positive regional lymph nodes (any T, N1-3, M0) have an average 5-year survival of approximately 40%, while those with distant metastases (any T, any N, M1) have an average 5-year survival of approximately 5%.[101]

CEA level is also directly related to the prognosis of disease, since its level correlates with the bulk of tumor tissue.

Follow-up

The aims of follow-up are to diagnose, in the earliest possible stage, any metastasis or tumors that develop later, but did not originate from the original cancer (metachronous lesions).

The U.S. National Comprehensive Cancer Network and American Society of Clinical Oncology provide guidelines for the follow-up of colon cancer.[102][103] A medical history and physical examination are recommended every 3 to 6 months for 2 years, then every 6 months for 5 years. Carcinoembryonic antigen blood level measurements follow the same timing, but are only advised for patients with T2 or greater lesions who are candidates for intervention. A CT-scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis can be considered annually for the first 3 years for patients who are at high risk of recurrence (for example, patients who had poorly differentiated tumors or venous or lymphatic invasion) and are candidates for curative surgery (with the aim to cure). A colonoscopy can be done after 1 year, except if it could not be done during the initial staging because of an obstructing mass, in which case it should be performed after 3 to 6 months. If a villous polyp, a polyp >1 centimeter or high grade dysplasia is found, it can be repeated after 3 years, then every 5 years. For other abnormalities, the colonoscopy can be repeated after 1 year.

Routine PET or ultrasound scanning, chest X-rays, complete blood count or liver function tests are not recommended.[102][103] These guidelines are based on recent meta-analyses showing intensive surveillance and close follow-up can reduce the 5-year mortality rate from 37% to 30%.[104][105][106]

Epidemiology

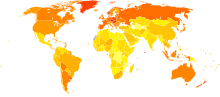

The incidence of colorectal cancer varies greatly between different regions of the world, much of it can be attributed to differences in diet, particularly the consumption of red and processed meat, fibre and alcohol, as well as bodyweight and physical activity.[107]

Incidence rates of colorectal cancer are increasing in countries where rates were previously low (especially in Japan, but also in other Asian countries) as diets become more Westernised, and either gradually increasing, stabilising (Northern and Western Europe) or declining (North America) with time. In 2008, almost 60% of cases were diagnosed in the developed world.[108]

Age-standardized death from colorectal cancer per 100,000 inhabitants in 2004.[109]

Age-standardized death from colorectal cancer per 100,000 inhabitants in 2004.[109] no dataless than 2.52.5-55-7.57.5-1010-12.512.5-1515-17.517.5-2020-22.522.5-2525-27.5more than 27.5

no dataless than 2.52.5-55-7.57.5-1010-12.512.5-1515-17.517.5-2020-22.522.5-2525-27.5more than 27.5Society and culture

Notable patients

Main article: List of people diagnosed with colorectal cancer- Corazon Aquino, former president of the Philippines[110]

- Pope John Paul II[111]

- Ronald Reagan[112]

- Harold Wilson, former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom[113]

See also

References

- ^ a b c http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats/types/bowel/survival/#stage

- ^ http://esa.un.org/unpp/index.asp?panel=5

- ^ a b http://globocan.iarc.fr/

- ^ Astin, M; Griffin, T, Neal, RD, Rose, P, Hamilton, W (2011 May). "The diagnostic value of symptoms for colorectal cancer in primary care: a systematic review". The British journal of general practice : the journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners 61 (586): 231–43. doi:10.3399/bjgp11X572427. PMC 3080228. PMID 21619747. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3080228.

- ^ Levin KE, Dozois RR (1991). "Epidemiology of large bowel cancer". World J Surg 15 (5): 562–7. doi:10.1007/BF01789199. PMID 1949852.

- ^ Penn State University health and disease information

- ^ Strate LL, Syngal S (April 2005). "Hereditary colorectal cancer syndromes". Cancer Causes Control 16 (3): 201–13. doi:10.1007/s10552-004-3488-4. PMID 15947872.

- ^ American Cancer Society Smoking Linked to Increased Colorectal Cancer Risk - New Study Links Smoking to Increased Colorectal Cancer Risk 6 December 2000

- ^ 'Smoking Ups Colon Cancer Risk' at Medline Plus

- ^ Chao A, Thun MJ, Connell CJ, et al. (January 2005). "Meat consumption and risk of colorectal cancer". JAMA 293 (2): 172–82. doi:10.1001/jama.293.2.172. PMID 15644544. http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=15644544.

- ^ "Red meat 'linked to cancer risk'". BBC News: Health. 15 June 2005. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/health/4088824.stm.

- ^ Park Y, Hunter DJ, Spiegelman D, et al. (December 2005). "Dietary fiber intake and risk of colorectal cancer: a pooled analysis of prospective cohort studies". JAMA 294 (22): 2849–57. doi:10.1001/jama.294.22.2849. PMID 16352792. http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=16352792.

- ^ The effect of lithocholic acid on proliferation and apoptosis during the early stages of colon carcinogenesis: differential effect on apoptosis in the presence of a colon carc...

- ^ Clark LC, Dalkin B, Krongrad A, et al. (May 1998). "Decreased incidence of prostate cancer with selenium supplementation: results of a double-blind cancer prevention trial". Br J Urol 81 (5): 730–4. PMID 9634050. http://pt.wkhealth.com/pt/re/bjui/abstract.00002414-199805000-00016.htm;jsessionid=JqcL016RGtWFPmKj7GL9x6zYp0znbqdF2xz0fbGz5RtW8mnlCK22!289474761!181195629!8091!-1.

- ^ Finley JW, Davis CD, Feng Y (September 2000). "Selenium from high selenium broccoli protects rats from colon cancer". J. Nutr. 130 (9): 2384–9. PMID 10958840. http://jn.nutrition.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=10958840.

- ^ a b Gregory L. Brotzman and Russell G. Robertson (2006). "Colorectal Cancer Risk Factors". Colorectal Cancer. Armenian Health Network, Health.am. http://www.health.am/cr/colorectal-cancer/. Retrieved 16 January 2008.

- ^ Jerome J. DeCosse, MD; George J. Tsioulias, MD; Judish S. Jacobson, MPH (February 1994). "Colorectal cancer: detection, treatment, and rehabilitation" (PDF). CA: a cancer journal for clinicians (A Cancer Journal for Clinicians) 44 (1): 27–42. doi:10.3322/canjclin.44.1.27. PMID 8281470. http://caonline.amcancersoc.org/cgi/reprint/44/1/27.pdf. Retrieved 16 January 2008.

- ^ Hamilton SR (August 1985). "Colorectal carcinoma in patients with Crohn's disease". Gastroenterology 89 (2): 398–407. PMID 2989075.

- ^ dos Santos Silva I, Swerdlow AJ (March 1996). "Sex differences in time trends of colorectal cancer in England and Wales: the possible effect of female hormonal factors". Br. J. Cancer 73 (5): 692–7. doi:10.1038/bjc.1996.120. PMC 2074327. PMID 8605109. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2074327.

- ^ Beral V, Banks E, Reeves G, Appleby P (1999). "Use of HRT and the subsequent risk of cancer". J Epidemiol Biostat 4 (3): 191–210; discussion 210–5. PMID 10695959.

- ^ a b c National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Alcohol and Cancer - Alcohol Alert No. 21-1993

- ^ Larsson, S.; Orsini, N.; Wolk, A. (2010). "Vitamin B6 and risk of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of prospective studies". Journal of the American Medical Association 303 (11): 1077–1083. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.263. PMID 20233826.

- ^ a b WCRF Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity and the Prevention of Cancer: a Global Perspective

- ^ Longnecker MP (1992). "Alcohol consumption in relation to risk of cancers of the breast and large bowel". Alcohol Health Res World 16 (3): 223–9.

- ^ Longnecker MP, Orza MJ, Adams ME, Vioque J, Chalmers TC (July 1990). "A meta-analysis of alcoholic beverage consumption in relation to risk of colorectal cancer". Cancer Causes Control 1 (1): 59–68. doi:10.1007/BF00053184. PMID 2151680.

- ^ Kune S, Kune GA, Watson LF (1987). "Case-control study of alcoholic beverages as etiological factors: the Melbourne Colorectal Cancer Study". Nutr Cancer 9 (1): 43–56. doi:10.1080/01635588709513909. PMID 3808969.

- ^ Potter JD, McMichael AJ (April 1986). "Diet and cancer of the colon and rectum: a case-control study". J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 76 (4): 557–69. PMID 3007842.

- ^ a b Cho E, Smith-Warner SA, Ritz J, et al. (April 2004). "Alcohol intake and colorectal cancer: a pooled analysis of 8 cohort studies". Ann. Intern. Med. 140 (8): 603–13. doi:10.1059/0003-4819-140-8-200404200-00007. PMID 15096331. http://www.annals.org/content/140/8/603.full.

- ^ Boston University "Alcohol May Increase the Risk of Colon Cancer"

- ^ Su LJ, Arab L (2004). "Alcohol consumption and risk of colon cancer: evidence from the national health and nutrition examination survey I epidemiologic follow-up study". Nutr Cancer 50 (2): 111–9. doi:10.1207/s15327914nc5002_1. PMID 15623458.

- ^ Anderson JC, Alpern Z, Sethi G, et al. (September 2005). "Prevalence and risk of colorectal neoplasia in consumers of alcohol in a screening population". Am. J. Gastroenterol. 100 (9): 2049–55. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41832.x. PMID 16128951.

- ^ Colorectal Cancer: Who's at Risk? (National Institutes of Health: National Cancer Institute)

- ^ National Cancer Institute (NCI) Cancer Trends Progress Report Alcohol Consumption

- ^ Brown, Anthony J. Alcohol, tobacco, and male gender up risk of earlier onset colorectal cancer

- ^ Ionov Y, Peinado MA, Malkhosyan S, Shibata D, Perucho M (1993). "Ubiquitous somatic mutations in simple repeated sequences reveal a new mechanism for colonic carcinogenesis". Nature 363 (6429): 558–61. doi:10.1038/363558a0. PMID 8505985.

- ^ Srikumar Chakravarthi, Baba Krishnan, Malathy Madhavan (1999). "Apoptosis and expression of p53 in colorectal neoplasms". Indian J Med Res 86 (7): 95–102.

- ^ a b c d Markowitz SD, Bertagnolli MM (December 2009). "Molecular Origins of Cancer: Molecular Basis of Colorectal Cancer". N. Engl. J. Med. 361 (25): 2449–60. doi:10.1056/NEJMra0804588. PMC 2843693. PMID 20018966. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2843693.

- ^ Mehlen P, Fearon ER (August 2004). "Role of the dependence receptor DCC in colorectal cancer pathogenesis". J. Clin. Oncol. 22 (16): 3420–8. doi:10.1200/JCO.2004.02.019. PMID 15310786.

- ^ Vogelstein, B.; Kinzler, K. W. (2004). "Cancer genes and the pathways they control". Nature Medicine 10 (8): 789–799. doi:10.1038/nm1087. PMID 15286780.

- ^ "Implementing Colorectal Cancer Screening. Workshop Summary". The National Academies Press. 11 December 2008. http://www.iom.edu/CMS/26765/60428.aspx. Retrieved 19 December 2008.

- ^ Weitzel JN (December 1999). "Genetic cancer risk assessment. Putting it all together". Cancer 86 (11 Suppl): 2483–92. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19991201)86:11+<2483::AID-CNCR5>3.0.CO;2-4. PMID 10630174.

- ^ [1] Koss K, Maxton D, Jankowski JA.(2008): Faecal dimeric M2 pyruvate kinase in colorectal cancer and polyps correlates with tumour staging and surgical intervention. Colorectal Dis. 2008 Mar;10(3):244-8. PMID 17784868

- ^ a b Total Levels of Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinases 1 in Plasma Yield High Diagnostic Sensitivity and Specificity in Patients with Colon Cancer — Clin Cancer Res

- ^ YM Lo (2001). "Circulating nucleic acids in plasma and serum: an overview". Ann N Y Acad Sci 945: 1–7. PMID 11708462.

- ^ Diehl F, Schmidt K, Choti MA, Romans K, Goodman S, Li M, Thornton K, Agrawal N, Sokoll L, Szabo SA, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Diaz LA Jr (2008). "Circulating mutant DNA to assess tumor dynamics". Nat Med 14 (9): 985–990. doi:10.1038/nm.1789. PMC 2820391. PMID 186700422. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2820391.

- ^ Lofton-Day C, Model F, Devos T, Tetzner R, Distler J, Schuster M, Song X, Lesche R, Liebenberg V, Ebert M, Molnar B, Grützmann R, Pilarsky C, Sledziewski A. (2008). "DNA methylation biomarkers for blood-based colorectal cancer screening". Clin Chem. 54 (2): 414–423. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2007.095992. PMID 18089654.

- ^ deVos T, Tetzner R, Model F, Weiss G, Schuster M, Distler J, Steiger KV, Grützmann R, Pilarsky C, Habermann JK, Fleshner PR, Oubre BM, Day R, Sledziewski AZ, Lofton-Day C. (2009). "Circulating methylated SEPT9 DNA in plasma is a biomarker for colorectal cancer". Clin Chem. 55 (7): 1337–1346. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2008.115808. PMID 19406918.

- ^ Detection of Colorectal Cancer in Peripheral Blood by Septin 9 DNA Methylation Assay - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov

- ^ Medical Tests : Warnex

- ^ *Payne S.R. (2010). "From discovery to the clinic: the novel DNA methylation biomarker mSEPT9 for the detection of colorectal cancer in blood". Epigenomics 2 (4): 575–585. doi:10.2217/epi.10.35.

- ^ B. Greenwald (2006). "The DNA Stool Test - An Emerging Technology in Colorectal Cancer Screening". http://www.touchalimentarydisease.com/articles.cfm?article_id=6375&level=2.

- ^ Blood test for inflammation may be sign of colon cancer

- ^ "Blood test for colon cancer promising: study". Reuters. 29 September 2010. http://www.reuters.com/article/idUSTRE68S5IO20100929.

- ^ Screening Tool Can Detect Colorectal Cancer from a Small Blood Sample

- ^ Exiqon Presents Data Supporting Use of PCR-Based miRNA Assay as Blood-Based Colon Cancer Dx | PCR Insider | PCR/Sample Prep | GenomeWeb

- ^ High plasma TIMP-1 and serum CEA levels during com... [Oncology. 2010] - PubMed result

- ^ Pathology atlas

- ^ AJCC Cancer Staging Manual (Sixth ed.). Springer-Verlag New York, Inc.. 2002.

- ^ Dukes CE (1932). "The classification of cancer of the rectum". Journal of Pathological Bacteriology 35 (3): 323. doi:10.1002/path.1700350303.

- ^ Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Ho MN, et al. (December 1993). "Prevention of colorectal cancer by colonoscopic polypectomy. The National Polyp Study Workgroup". N. Engl. J. Med. 329 (27): 1977–81. doi:10.1056/NEJM199312303292701. PMID 8247072. http://content.nejm.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=short&pmid=8247072&promo=ONFLNS19.

- ^ N.N. Baxter, M.A. Goldwasser, L.F. Paszat, R. Saskin, D.R. Urbach, and L. Rabeneck, "Association of Colonoscopy and Death from Colorectal Cancer: A Population-Based, Case–Control Study," Annals of Internal Medicine, Volume 150 Issue 1, 6 January 2009 article; (see also summary version, Effectiveness of Colonoscopy for Prevention of Mortality From Colorectal Cancer accessed December 22, 2009)

- ^ "Real-world colonoscopy benefit seen more limited". Reuters. December 16, 2008. http://uk.reuters.com/article/healthNewsMolt/idUKTRE4BF6LJ20081216?pageNumber=1&virtualBrandChannel=0.

- ^ Cummings, JH; Bingham SA (1998). "Diet and the prevention of cancer". BMJ 317 (7173): 1636–40. PMC 1114436. PMID 9848907. http://bmj.bmjjournals.com/.

- ^ Fuchs, C. S.; Giovannucci, EL; Colditz, GA; Hunter, DJ; Stampfer, MJ; Rosner, B; Speizer, FE; Willett, WC (1999). "Dietary Fiber and the Risk of Colorectal Cancer and Adenoma in Women". New England Journal of Medicine 340 (3): 169–76. doi:10.1056/NEJM199901213400301. PMID 9895396. http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/full/340/3/169.

- ^ Baron, J. A.; Hunter, DJ; Spiegelman, D; Bergkvist, L; Berrino, F; Van Den Brandt, PA; Buring, JE; Colditz, GA et al. (2005). "Dietary Fiber and Colorectal Cancer: An Ongoing Saga". Journal of the American Medical Association 294 (22): 2904–6. doi:10.1001/jama.294.22.2904. PMID 16352800.

- ^ "Health Effects of Eating Fiber". http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/fiber.html.

- ^ Samad, A. K. A.; Taylor, RS; Marshall, T; Chapman, MAS (2004). "A meta-analysis of the association of physical activity with reduced risk of colorectal cancer". Colorectal Disease 7 (3): 204–13.

- ^ "Colorectal Cancer Prevention: Chemoprevention Database". http://www.inra.fr/internet/Projets/reseau-nacre/sci-memb/corpet/indexan.html. Retrieved 23 August 2007.

- ^ Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (5 March 2007). "Task Force Recommends Against Use of Aspirin and Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs to Prevent Colorectal Cancer". United States Department of Health & Human Services. http://www.ahrq.gov/news/press/pr2007/aspnsaidpr.htm. Retrieved 7 May 2007.

- ^ U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (March 2007). "Routine aspirin or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the primary prevention of colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement". Ann. Intern. Med. 146 (5): 361–4. PMID 17339621.

- ^ Flossmann E, Rothwell PM (May 2007). "Effect of aspirin on long-term risk of colorectal cancer: consistent evidence from randomized and observational studies". Lancet 369 (9573): 1603–13. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60747-8. PMID 17499602. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140-6736(07)60747-8.

- ^ Campbell CL, Smyth S, Montalescot G, Steinhubl SR (2007). "Aspirin dose for the prevention of cardiovascular disease: a systematic review". JAMA 297 (18): 2018–24. doi:10.1001/jama.297.18.2018. PMID 17488967.

- ^ Weingarten MA, Zalmanovici A, Yaphe J (2005). Weingarten, Michael Asher. ed. "Dietary calcium supplementation for preventing colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (3): CD003548. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003548.pub3. PMID 16034903.

- ^ Wactawski-Wende J, Kotchen JM, Anderson GL, et al. (2006). "Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and the risk of colorectal cancer". N. Engl. J. Med. 354 (7): 684–96. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa055222. PMID 16481636.

- ^ Lappe JM, Travers-Gustafson D, Davies KM, Recker RR, Heaney RP (2007). "Vitamin D and calcium supplementation reduces cancer risk: results of a randomized trial". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 85 (6): 1586–91. PMID 17556697. http://www.ajcn.org/cgi/content/full/85/6/1586.

- ^ Freedman DM, Looker AC, Chang SC, Graubard BI (2007). "Prospective study of serum vitamin D and cancer mortality in the United States". J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 99 (21): 1594–602. doi:10.1093/jnci/djm204. PMID 17971526.

- ^ Bijlsma MF, Spek CA, Zivkovic D, van de Water S, Rezaee F, Peppelenbosch MP (2006). "Repression of Smoothened by Patched-Dependent (Pro-)Vitamin D3 Secretion". PLoS Biol 4 (8): e232. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040232. PMC 1502141. PMID 16895439. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1502141.

- ^ Ades, Steven (2009). "Adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer in the elderly". [Oncology]. http://www.cancernetwork.com/display/article/10165/1376671.

- ^ Parker MC, Wilson MS, Menzies D, Sunderland G, Clark DN, Knight AD, Crowe AM; Surgical and Clinical Adhesions Research (SCAR) Group. (2005). "The SCAR-3 study: 5-year adhesion-related readmission risk following lower abdominal surgical procedures". Colorectal Dis. 7 (6): 551–558. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1318.2005.00857.x. PMID 16232234. http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/118740522/abstract?CRETRY=1&SRETRY=0. Retrieved 5 March 2009.

- ^ http://saci.uthscsa.edu/ClinicalTrials/SelectedPhase1.html#PhINovel

- ^ a b L. van Epps, PhD, Heather (Winter, 2008). "Bittersweet Gene: A gene called KRAS can predict which colorectal cancers will respond to a certain type of treatment—and which will not.". CURE (Cancer Updates, Research and Education). http://www.curetoday.com/index.cfm/fuseaction/article.show/id/2/article_id/943.

- ^ ASCO Releases Provisional Clinical Opinion Recommending Routine KRAS Gene Testing to Guide Treatment for Metastatic Colorectal Cancer

- ^ OncoGenetics.Org (July 2009). "FDA updates Vectibix and Erbitux labels with KRAS testing info". OncoGenetics.Org. http://www.oncogenetics.org/web/fda-updates-vectibix-and-erbitux-labels-with-kras-testing-info. Retrieved 20 July 2009.[dead link]

- ^ V. Shankaran, et al. "Economic implications of Kras testing in metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC)" ASCO 2009 Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium, abstract #298; http://www.asco.org/ASCO/Abstracts+&+Virtual+Meeting/Abstracts?&vmview=abst_detail_view&confID=63&abstractID=10759.

- ^ http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/supportivecare/gastrointestinalcomplications/Patient/page7

- ^ Informa Healthcare - International Journal of Hyperthermia - 26(2):108 - Summary

- ^ Mosolits S, Nilsson B, Mellstedt H (June 2005). "Towards therapeutic vaccines for colorectal carcinoma: a review of clinical trials". Expert Rev Vaccines 4 (3): 329–50. doi:10.1586/14760584.4.3.329. PMID 16026248. http://www.future-drugs.com/doi/abs/10.1586/14760584.4.3.329?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3dncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- ^ Wheldon, Julie. Vaccine for kidney and bowel cancers 'within three years' The Daily Mail 13 November 2006

- ^ Oxford BioMedica

- ^ Vaccine Works With Chemotherapy in Colorectal Cancer (Reuters) 13 August 2007

- ^ http://www.cancer.org/docroot/PRO/content/PRO_1_1_Cancer_Statistics_2006_Presentation.asp

- ^ Simmonds PC, Primrose JN, Colquitt JL, Garden OJ, Poston GJ, Rees M (April 2006). "Surgical resection of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer: A systematic review of published studies". Br. J. Cancer 94 (7): 982–99. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6603033. PMC 2361241. PMID 16538219. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2361241.

- ^ Chan AT, Giovannucci EL, Meyerhardt JA, Schernhammer ES, Curhan GC, Fuchs CS (August 2005). "Long-term Use of Aspirin and Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs and Risk of Colorectal Cancer". JAMA 294 (8): 914–23. doi:10.1001/jama.294.8.914. PMC 1550973. PMID 16118381. http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=16118381.

- ^ Chan AT, Ogino S, Fuchs CS (August 2009). "Aspirin Use and Survival After Diagnosis of Colorectal Cancer". JAMA 302 (6): 649–58. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1112. PMC 2848289. PMID 19671906. http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=19671906.

- ^ Jeffrey A. Gordon, M.D. Aspirin Use as Treatment in Colorectal Cancer: Teaching an Old Dog New Tricks. Doctors Lounge Website. Available at: http://www.doctorslounge.com/index.php/articles/page/298. Accessed September 20, 2009.

- ^ Matsumoto S, Hayashi A, Kobayashi K, Imaeda Y, Umemoto S (February 2004). Cimetidine blocking of E-selectin expression inhibits sialyl Lewis-X-positive cancer cells from adhering to vascular endothelium. http://www.cancerprev.org/Meetings/2004/Symposia/1094/138.

- ^ Matsumoto S, Imaeda Y, Umemoto S, Kobayashi K, Okamoto T (january 2002). "Cimetidine increases survival of colorectal cancer patients with high levels of sialyl Lewis-X and sialyl Lewis-A epitope expression on tumour cells". British Journal of Cancer 86 (6): 161–167. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6600048. PMC 2375187. PMID 11870500. http://www.nature.com/bjc/journal/v86/n2/abs/6600048a.html.

- ^ Yoshimatsu K, Ishibashi K, Hashimoto M, Umehara A, Yokomizo H, Yoshida K, Fujimoto T, Iwasaki K, Ogawa K (October 2003). "Effect of cimetidine with chemotherapy on stage IV colorectal cancer [Article in Japanese"]. Gan to Kagaku Ryoho. 30 (11): 1794–7. PMID 14619522. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14619522.

- ^ Wasserberg N, Kaufman HS (December 2007). "Palliation of colorectal cancer". Surg Oncol 16 (4): 299–310. doi:10.1016/j.suronc.2007.08.008. PMID 17913495.

- ^ Amersi F, Stamos MJ, Ko CY (July 2004). "Palliative care for colorectal cancer". Surg. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 13 (3): 467–77. doi:10.1016/j.soc.2004.03.002. PMID 15236729.

- ^ Box 3-1, Page 107 in: Elizabeth D Agabegi; Agabegi, Steven S. (2008). Step-Up to Medicine (Step-Up Series). Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-7817-7153-6.

- ^ a b NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology - Colon Cancer (version 1, 2008: September 19, 2007).

- ^ a b Desch CE, Benson AB 3rd, Somerfield MR, et al.; American Society of Clinical Oncology (2005). "Colorectal cancer surveillance: 2005 update of an American Society of Clinical Oncology practice guideline" (PDF). J Clin Oncol 23 (33): 8512–9. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.04.0063. PMID 16260687. http://jco.ascopubs.org/cgi/reprint/JCO.2005.04.0063v1.pdf.

- ^ Jeffery M, Hickey BE, Hider PN (2002). Jeffery, Mark. ed. "Follow-up strategies for patients treated for non-metastatic colorectal cancer". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD002200. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002200. PMID 11869629. CD002200. http://mrw.interscience.wiley.com/cochrane/clsysrev/articles/CD002200/frame.html.

- ^ Renehan AG, Egger M, Saunders MP, O'Dwyer ST (2002). "Impact on survival of intensive follow up after curative resection for colorectal cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials". BMJ 324 (7341): 831–8. doi:10.1136/bmj.324.7341.813. PMC 100789. PMID 11934773. http://www.bmj.com/cgi/reprint/324/7341/813.

- ^ Figueredo A, Rumble RB, Maroun J, et al.; Gastrointestinal Cancer Disease Site Group of Cancer Care Ontario's Program in Evidence-based Care. (2003). "Follow-up of patients with curatively resected colorectal cancer: a practice guideline". BMC Cancer 3: 26. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-3-26. PMC 270033. PMID 14529575. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=270033.

- ^ CancerStats, Cancer Research UK, "Cancer Worldwide - Colorectal Cancer", September 2011 http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats/world/colorectal-cancer-world/#Incidence

- ^ CancerStats, Cancer Research UK, "Cancer Worldwide - Colorectal Cancer", September 2011 http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats/world/colorectal-cancer-world/

- ^ "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2009. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/estimates_country/en/index.html. Retrieved Nov. 11, 2009.

- ^ http://www.abs-cbnnews.com/storypage.aspx?StoryID=112887

- ^ "Pope John Paul II". ABC News Online. http://www.abc.net.au/news/indepth/pope/timeline.htm.

- ^ "Reagan turns 90". BBC News: Americas. 6 February 2001. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/1156513.stm.

- ^ Daily Mail

External links

- American Cancer Society's Detailed Guide: Colon and Rectum Cancer

- Clinically reviewed bowel cancer information for patients, from Cancer Research UK

- UK bowel cancer statistics from Cancer Research UK

- Colorectal cancer at the Open Directory Project

- ColonCancerCheck including fact sheets in 24 languages at Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care

Tumors: digestive system neoplasia (C15–C26/D12–D13, 150–159/211) GI tract Upper GI tractGastric carcinoma · Signet ring cell carcinoma · Gastric lymphoma (MALT lymphoma) · Linitis plasticaColon/rectumUpper and/or lowerAccessory exocrine pancreas: Adenocarcinoma · Pancreatic ductal carcinoma

cystic neoplasms: Serous microcystic adenoma · Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm · Mucinous cystic neoplasm · Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm

PancreatoblastomaPeritoneum Categories:- Conditions diagnosed by stool test

- Deaths from colorectal cancer

- Gastrointestinal cancer

- Rectum

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.