- Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

-

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease Classification and external resources

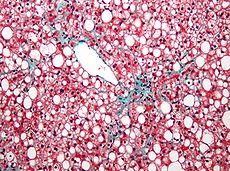

Micrograph of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, demonstrating marked macrovesicular steatosis. Trichrome stain.ICD-10 K76.0 ICD-9 571.8 DiseasesDB 29786 eMedicine med/775 Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is one cause of a fatty liver, occurring when fat is deposited (steatosis) in the liver not due to excessive alcohol use. It is related to insulin resistance and the metabolic syndrome and may respond to treatments originally developed for other insulin-resistant states (e.g. diabetes mellitus type 2) such as weight loss, metformin and thiazolidinediones.[1] Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is the most extreme form of NAFLD this being regarded as a major cause of cirrhosis of the liver of unknown cause.[2]

Contents

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms and associations

Most patients with NAFLD have few or no symptoms. Patients may complain of fatigue, malaise, and dull right-upper-quadrant abdominal discomfort. Mild jaundice may be noticed although this is rare. More commonly NAFLD is diagnosed following abnormal liver function tests during routine blood tests. By definition, alcohol consumption of over 20 g/day (about 25 ml/day) excludes the condition.[1]

NAFLD is associated with insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome (obesity, combined hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus (type II) and high blood pressure).[1][2]

Secondary causes

NAFLD can also be caused by some medications:[1]

- Amiodarone

- Antiviral drugs (nucleoside analogues)

- Aspirin rarely as part of Reye's syndrome in children

- Corticosteroids

- Methotrexate

- Tamoxifen

- Tetracycline

Diagnosis

Common findings are elevated liver enzymes and a liver ultrasound showing steatosis. An ultrasound may also be used to exclude gallstone problems (cholelithiasis). A biopsy (tissue examination) of the liver is the only test widely accepted as definitively distinguishing NASH from other forms of liver disease and can be used to assess the severity of the inflammation and resultant fibrosis.[1]

Non-invasive diagnostic tests have been developed, such as FibroTest, that estimates liver fibrosis,[3] and SteatoTest, that estimates steatosis,[4] however their use has not been widely adopted.[5] Apoptosis has been shown to be the mechanism of hepatocyte destruction and caspase-cleaved cytokeratin 18 (M30-Apoptosense ELISA) in serum/plasma is often elevated in patients with NASH.[6][7]

Other diagnostic tests are available. Relevant blood tests include erythrocyte sedimentation rate, glucose, albumin, and renal function. Because the liver is important for making proteins used in coagulation some coagulation related studies are often carried out especially the INR (international normalized ratio). Blood tests (serology) are usually used to rule out viral hepatitis (hepatitis A, B, C, EBV, CMV and herpes viruses), rubella, and autoimmune related diseases. Hypothyroidism is more prevalent in NASH patients which would be detected by determining the TSH.[8]

It has been suggested that in cases involving overweight patients whose blood tests do not improve on losing weight and exercising that a further search of other underlying causes be undertaken. This would also apply to those with fatty liver that are very young or not overweight or insulin-resistant. In addition those whose physical appearance indicates the possibility of a congenital syndrome, have a family history of liver disease, have abnormalities in other organs, and those that present with moderate to advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis.[9]

Pathophysiology

NAFLD is considered to cover a spectrum of disease activity. This spectrum begins as fatty accumulation in the liver (hepatic steatosis). A liver can remain fatty without disturbing liver function, but by varying mechanisms and possible insults to the liver may also progress to outright inflammation of the liver. When inflammation occurs in this setting, the condition is then called NASH. Over time, up to 20 percent of patients with NASH may develop cirrhosis.[citation needed] Cigarette smoking is not associated with an increased risk of developing NASH.

The exact cause of NAFLD is still unknown. However, both obesity and insulin resistance probably play a strong role in the disease process. The exact reasons and mechanisms by which the disease progresses from one stage to the next are not known.

One debated mechanism proposes a "second hit", or further injury, enough to cause change that leads from hepatic steatosis to hepatic inflammation. Oxidative stress, hormonal imbalances, and mitochondrial abnormalities are potential causes for this "second hit" phenomenon.[1]

Dietary Influences

Soft drink (SD) consumption—specifically high-fructose corn syrup SD consumption—has become a major concern in public health. 80% of NAFLD patients with or without metabolic syndrome had excessive intake of SD (>500 cm3/day or >12 teaspoons/day added sugar) compared to the 17% healthy controls (P-value <0.001; Confidence Interval=95%).[10] This included Coca-Cola (both regular and diet) and fruit juices as the most common SD sources. Another study suggests that 31 g/day in SD sugar intake raises the odds ratio for NAFLD to 1.45 times with 95% confidence.[11] Metabolically, phosphorylation of fructose by fructokinase is specific and not rate-limited causing human hepatic ATP depletion.[12] Ultimately, this leads to lipogenesis, which increases NAFLD risk.

Genetics

Indian men have a high prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Two genetic mutations for this susceptibility have been identified, and these mutations provided clues to the mechanism of NASH and related diseases.

Polymorphisms (genetic variations) in the single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) T455C and C482T in APOC3 are associated with fatty liver disease, insulin resistance, and possibly hypertriglyceridemia. 95 healthy Asian Indian men and 163 healthy non-Asian Indian men around New Haven, Connecticut were genotyped for polymorphisms in those SNPs. 20% homogeneous wild both loci. Carriers of T-455C, C-482T, or both (not additive) had a 30% increase in fasting plasma apolipoprotein C3, 60% increase in fasting plasma triglyceride and retinal fatty acid ester, and 46% reduction in plasma triglyceride clearance. Prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease was 38% in carriers, 0% wild (normal). Subjects with fatty liver disease had marked insulin resistance.[13]

Treatment

A large number of treatments for NAFLD have been studied. While many appear to improve biochemical markers such as alanine transaminase levels, most have not been shown to reverse histological abnormalities or reduce clinical endpoints:.[1]

- Treatment of nutrition and excessive body weight:

- Nutritional counseling: Diet changes have shown significant histological improvement.[14]

- Weight loss: gradual weight loss may improve the process in obese patients; rapid loss may worsen NAFLD. The negative effects of rapid weight loss are controversial: the results of a meta-analysis showed that the risk of progression is very low.[1]

- A recent meta-analysis presented at the Annual Meeting of American Association for Study of Liver Diseases(AASLD) reported that weight-loss surgery leads to improvement and or resolution of NASH in around 80 % of patients.[2]

- Insulin sensitisers (metformin[15] and thiazolidinediones[16]) have shown efficacy in some studies.

- ursodeoxycholic acid and lipid-lowering drugs, have little benefit.[citation needed]

Vitamin E can improve some symptoms of NASH and was superior to insulin sensitizer in one large study. In the Pioglitazone versus Vitamin E versus Placebo for the Treatment of Nondiabetic Patients with Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis (PIVENS) trial, for patients with NASH but without diabetes mellitus, the use of very high dosages of vitamin E (800 IU/day) for four years was associated with a significantly higher rate of improvement than placebo (43% vs. 19%) in the primary outcome. The primary outcome was an improvement in certain histological features as measured by biopsy—but it did not improve fibrosis. Pioglitazone, an insulin sensitizer, improved some features of NASH but not the primary outcome, and resulted in a significant weight gain (mean 4.7 kilograms) which persisted after pioglitazone was discontinued.[17]

In a study using the NHANES III dataset, it has been shown that mild alcohol consumption (one glass of wine a day) reduces the risk of NAFLD by half.[18]

See also

- Fatty liver includes both non-alcoholic and alcoholic liver disease

- Alcoholic liver disease

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Adams LA, Angulo P (2006). "Treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease". Postgrad Med J 82 (967): 315–22. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2005.042200. PMC 2563793. PMID 16679470. http://pmj.bmj.com/cgi/content/full/82/967/315.

- ^ a b Clark JM, Diehl AM (2003). "Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: an underrecognized cause of cryptogenic cirrhosis". JAMA 289 (22): 3000–4. doi:10.1001/jama.289.22.3000. PMID 12799409.

- ^ Halfon P, Munteanu M, Poynard T (2008). "FibroTest-ActiTest as a non-invasive marker of liver fibrosis". Gastroenterol Clin Biol 32 (6): 22–39. doi:10.1016/S0399-8320(08)73991-5. PMID 18973844.

- ^ Ratziu et al; Massard, J; Charlotte, F; Messous, D; Imbert-Bismut, F; Bonyhay, L; Tahiri, M; Munteanu, M et al. (2006). "Diagnostic value of biochemical markers (FibroTest-FibroSURE) for the prediction of liver fibrosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease". BMC Gastroenterology 14: 6. doi:10.1186/1471-230X-6-6. PMC 1386692. PMID 16503961. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1386692.

- ^ Vuppalanchi R, Chalasani N (2009). "Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis: Selected Practical Issues in Their Evaluation and Management". Hepatology 49 (1): 306–317. doi:10.1002/hep.22603. PMC 2766096. PMID 19065650. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2766096.

- ^ Feldstein AE et al. (2009). "Cytokeratin-18 fragment levels as noninvasive biomarkers for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a multicenter validation study". Hepatology 50 (4): 1072–8. doi:10.1002/hep.23050. PMC 2757511. PMID 19585618. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2757511.

- ^ Musso G et al. (2010). "Meta-analysis: Natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and diagnostic accuracy of non-invasive tests for liver disease severity". Ann Med.: 1–33. doi:10.3109/07853890.2010.518623. PMID 21039302.

- ^ Liangpunsakul S, Chalasani N (2003). "Is hypothyroidism a risk factor for non-alcoholic steatohepatitis?". J Clin Gastroenterol 37 (4): 340–3. doi:10.1097/00004836-200310000-00014. PMID 14506393.

- ^ Cassiman D, Jaeken J (February 2008). "NASH may be trash". Gut 57 (2): 141–4. doi:10.1136/gut.2007.123240. PMID 18192446.

- ^ Abid, Ali; Taha O; Nseir W; Farah R; Grosovski M; Assy N (November 2009). "Soft drink consumption is associated with fatty liver disease independent of metabolic syndrome". Journal of Hepatology 51 (5): 918-924. http://www.jhep-elsevier.com/article/S0168-8278(09)00532-7/abstract. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- ^ Zelber-Sagi, Shira; Nitzan-Kaluski D; Goldsmith R; Webb M; Blendis L; Halpern Z; Oren R (November 2007). "Long term nutritional intake and the risk for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): A population based study". Journal of Hepatology 47 (5): 711-717. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17850914. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- ^ Nseir, William; Nassar F; Assy N (7). "Soft drinks consumption and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease". World Journal of Gastroenterology 16 (21): 2579-2588. http://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i21/2579.htm. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- ^ Petersen KF, Dufour S, Hariri A, et al. (March 2010). "Apolipoprotein C3 gene variants in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease". N. Engl. J. Med. 362 (12): 1082–9. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0907295. PMC 2976042. PMID 20335584. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2976042.

- ^ Huang MA, Greenson JK, Chao C, et al. (2005). "One-year intense nutritional counseling results in histological improvement in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: a pilot study". Am. J. Gastroenterol. 100 (5): 1072–81. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41334.x. PMID 15842581.

- ^ Bugianesi E, Gentilcore E, Manini R, et al. (2005). "A randomized controlled trial of metformin versus vitamin E or prescriptive diet in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease". Am. J. Gastroenterol. 100 (5): 1082–90. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41583.x. PMID 15842582.

- ^ Belfort R, Harrison SA, Brown K, et al. (2006). "A placebo-controlled trial of pioglitazone in subjects with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis". N. Engl. J. Med. 355 (22): 2297–307. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa060326. PMID 17135584.

- ^ Sanyal AJ, Chalasani N, Kowdley KV, et al. (May 2010). "Pioglitazone, vitamin E, or placebo for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis". N. Engl. J. Med. 362 (18): 1675–85. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0907929. PMC 2928471. PMID 20427778. http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/abstract/362/18/1675.

- ^ Dunn W, Xu R, Schwimmer JB (February 2008). "Modest wine drinking and decreased prevalence of suspected nonalcoholic fatty liver disease". Hepatology 47 (6): 1947–1954. doi:10.1002/hep.22292. PMID 18454505.

External links

- Medscape article on NASH.

- MEDICINENET article on Steatosis.

- NIH page on Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis

- British Medical Journal article on the diagnosis and initial management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

Categories:- Diseases of liver

- Hepatitis

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.