- Gallstone

-

Gallstone Classification and external resources

Numerous small gallstones, composed largely of cholesterolICD-10 K80 ICD-9 574 OMIM 600803 DiseasesDB 2533 MedlinePlus 000273 eMedicine emerg/97 MeSH D042882 A gallstone is a crystalline concretion formed within the gallbladder by accretion of bile components. These calculi are formed in the gallbladder, but may pass distally into other parts of the biliary tract such as the cystic duct, common bile duct, pancreatic duct, or the ampulla of Vater.

Presence of gallstones in the gallbladder may lead to acute cholecystitis, an inflammatory condition characterized by retention of bile in the gallbladder and often secondary infection by intestinal microorganisms, predominantly Escherichia coli and Bacteroides species. Presence of gallstones in other parts of the biliary tract can cause obstruction of the bile ducts, which can lead to serious conditions such as ascending cholangitis or pancreatitis. Either of these two conditions can be life-threatening, and are therefore considered to be medical emergencies.

Contents

Definitions

Presence of stones in the gallbladder is referred to as cholelithiasis (from the Greek: chol-, "bile" + lith-, "stone" + iasis-, "process"). If gallstones migrate into the ducts of the biliary tract, the condition is referred to as choledocholithiasis (from the Greek: chol-, "bile" + docho-, "duct" + lith-, "stone" + iasis-, "process"). Choledocholithiasis is frequently associated with obstruction of the biliary tree, which in turn can lead to acute ascending cholangitis (from the Greek: chol-, "bile + ang-, "vessel" + itis-, "inflammation"), a serious infection of the bile ducts. Gallstones within the ampulla of Vater can obstruct the exocrine system of the pancreas, which in turn can result in pancreatitis.

Characteristics and composition

Gallbladder opened to show numerous gallstones. The large, yellowish calculus is probably composed largely of cholesterol, while the greenish to brownish color of the other stones suggests these are composed of bile pigments such as biliverdin and stercobilin.

Gallbladder opened to show numerous gallstones. The large, yellowish calculus is probably composed largely of cholesterol, while the greenish to brownish color of the other stones suggests these are composed of bile pigments such as biliverdin and stercobilin. Images of a CT of gallstones

Images of a CT of gallstones

Gallstones can vary in size from as small as a grain of sand to as large as a golf ball. [1] The gallbladder may contain a single large stone or many smaller ones. Pseudoliths, sometime referred to as sludge, are thick secretions that may be present within the gallbladder, either alone or in conjunction with fully formed gallstones. The clinical presentation is similar to that of cholelithiasis.[citation needed] The composition of gallstones is affected by age, diet and ethnicity.[2] On the basis of their composition, gallstones can be divided into the following types:

- Cholesterol stones

Cholesterol stones vary in color from light-yellow to dark-green or brown and are oval 2 to 3 cm in length, often having a tiny dark central spot. To be classified as such, they must be at least 80% cholesterol by weight (or 70%, according to the Japanese classification system).[3]

- Pigment stones

Pigment stones are small, dark stones made of bilirubin and calcium salts that are found in bile. They contain less than 20% of cholesterol (or 30%, according to the Japanese classification system).[3]

- Mixed stones

Mixed gallstones typically contain 20–80% cholesterol (or 30–70%, according to the Japanese classification system).[3] Other common constituents are calcium carbonate, palmitate phosphate, bilirubin, and other bile pigments. Because of their calcium content, they are often radiographically visible.

Cholelithiasis

Signs and symptoms

Gallstones may be asymptomatic, even for years. These gallstones are called "silent stones" and do not require treatment.[4][5] Symptoms commonly begin to appear once the stones reach a certain size (>8 mm).[6] A characteristic symptom of gallstones is a "gallstone attack", in which a person may experience intense pain in the upper-right side of the abdomen, often accompanied by nausea and vomiting, that steadily increases for approximately 30 minutes to several hours. A patient may also experience referred pain between the shoulder blades or below the right shoulder. These symptoms may resemble those of a "kidney stone attack". Often, attacks occur after a particularly fatty meal and almost always happen at night. Other symptoms include abdominal bloating, intolerance of fatty foods, belching, gas, and indigestion.

A positive Murphy's sign is a common finding on physical examination.

Causes

Gallstone risk factors include overweight, age near or above 40, female, or pre-menopausal;[7] the condition is more prevalent in caucasians than in people of other races. A lack of melatonin could significantly contribute to gallbladder stones, as melatonin both inhibits cholesterol secretion from the gallbladder, enhances the conversion of cholesterol to bile, and is an antioxidant, capable of reducing oxidative stress to the gallbladder.[8] Researchers believe that gallstones may be caused by a combination of factors, including inherited body chemistry, body weight, gallbladder motility (movement), and perhaps diet. The absence of such risk factors does not, however, preclude the formation of gallstones.

No clear relationship has been proven between diet and gallstone formation; however, low-fiber, high-cholesterol diets and diets high in starchy foods have been suggested as contributing to gallstone formation. Other nutritional factors that may increase risk of gallstones include rapid weight loss, constipation, eating fewer meals per day, eating less fish, and low intakes of the nutrients folate, magnesium, calcium, and vitamin C.[9] On the other hand, wine and whole-grain bread may decrease the risk of gallstones.[10] Pigment gallstones are most commonly seen in the developing world. Risk factors for pigment stones include hemolytic anemias (such as sickle-cell disease and hereditary spherocytosis), cirrhosis, and biliary tract infections.[11] People with erythropoietic protoporphyria (EPP) are at increased risk to develop gallstones[12][13]. Additionally, prolonged use of proton pump inhibitors has been shown to decrease gallbladder function, potentially leading to gallstone formation[14].

Pathophysiology

Cholesterol gallstones develop when bile contains too much cholesterol and not enough bile salts. Besides a high concentration of cholesterol, two other factors are important in causing gallstones. The first is how often and how well the gallbladder contracts; incomplete and infrequent emptying of the gallbladder may cause the bile to become overconcentrated and contribute to gallstone formation. The second factor is the presence of proteins in the liver and bile that either promote or inhibit cholesterol crystallization into gallstones. In addition, increased levels of the hormone estrogen as a result of pregnancy, hormone therapy, or the use of combined (estrogen-containing) forms of hormonal contraception, may increase cholesterol levels in bile and also decrease gallbladder movement, resulting in gallstone formation.

Diagnosis

A 1.9 cm gallstone impacted in the neck of the gallbladder and leading to cholecystitis as seen on ultrasound. Note the 4 mm gall bladder wall thickening.

Treatment

- Medical

Cholesterol gallstones can sometimes be dissolved by oral ursodeoxycholic acid, but it may be necessary for the patient to take this medication for up to two years.[15] Gallstones may recur, however, once the drug is stopped. Obstruction of the common bile duct with gallstones can sometimes be relieved by endoscopic retrograde sphincterotomy (ERS) following endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Gallstones can be broken up using a procedure called extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (often simply called "lithotripsy"),[15] which is a method of concentrating ultrasonic shock waves onto the stones to break them into tiny pieces. They are then passed safely in the feces. However, this form of treatment is suitable only when there is a small number of gallstones.

- Surgical

Cholecystectomy (gallbladder removal) has a 99% chance of eliminating the recurrence of cholelithiasis. Only symptomatic patients must be indicated to surgery. The lack of a gallbladder may have no negative consequences in many people. However, there is a portion of the population — between 10 and 15% — who develop a condition called postcholecystectomy syndrome[16] which may cause gastrointestinal distress and persistent pain in the upper-right abdomen, as well as a 10% chance of developing chronic diarrhea.[17]

There are two surgical options for cholecystectomy:

- Open cholecystectomy: This procedure is performed via an incision into the abdomen (laparotomy) below the right lower ribs. Recovery typically consists of 3–5 days of hospitalization, with a return to normal diet a week after release and normal activity several weeks after release.[4]

- Laparoscopic cholecystectomy: This procedure, introduced in the 1980s,[18] is performed via three to four small puncture holes for a camera and instruments. Post-operative care typically includes a same-day release or a one night hospital stay, followed by a few days of home rest and pain medication.[4] Laparoscopic cholecystectomy patients can, in general, resume normal diet and light activity a week after release, with some decreased energy level and minor residual pain continuing for a month or two. Studies have shown that this procedure is as effective as the more invasive open cholecystectomy, provided the stones are accurately located by cholangiogram prior to the procedure so that they can all be removed.[citation needed]

Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy is a treatment in which shock waves are generated in water by lithotripters (devices that produce the waves). There are several types of lithotripters available for gallbladder removal. One specific lithotripter involves the use of piezoelectric crystals, which allow the shock waves to be accurately focused on a small area to disrupt a stone. This procedure does not generally require analgesia (or anesthesia). Damage to the gallbladder and associated structures (such as the cystic duct) must be present for stone removal after the shock waves break up the stone. Typically, repeated shock wave treatments are necessary to completely remove gallstones. The success rate of the fragmentation of the gallstone and urinary clearance is inversely proportional to stone size and number: patients with a small solitary stone have the best outcome, with high rates of stone clearance (95% are cleared within 12–18 months), while patients with multiple stones are at risk for poor clearance rates. Complications of shock wave lithotripsy include inflammation of the pancreas (pancreatitis) and acute cholecystitis.

Choledocholithiasis

Choledocholithiasis is the presence of gallstones in the common bile duct. This condition causes jaundice and liver cell damage, and requires treatment by cholecystectomy and/or ERCP.

Signs and symptoms

A positive Murphy's sign is a common finding on physical examination. Jaundice of the skin or eyes is an important physical finding in biliary obstruction. Jaundice and/or clay-colored stool may raise suspicion of choledocholithiasis or even gallstone pancreatitis.[4] If the above symptoms coincide with fever and chills, the diagnosis of ascending cholangitis may also be considered.

Causes

While stones can frequently pass through the common bile duct (CBD) into the duodenum, some stones may be too large to pass through the CBD and may cause an obstruction. One risk factor for this is duodenal diverticulum.

Pathophysiology

This obstruction may lead to jaundice, elevation in alkaline phosphatase, increase in conjugated bilirubin in the blood and increase in cholesterol in the blood. It can also cause acute pancreatitis and ascending cholangitis.

Diagnosis

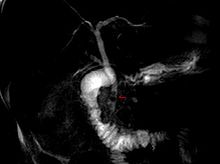

Common bile duct stone impacted at ampulla of Vater seen at time of ERCP

Common bile duct stone impacted at ampulla of Vater seen at time of ERCP

Choledocholithiasis (stones in common bile duct) is one of the complications of cholelithiasis (gallstones), so the initial step is to confirm the diagnosis of cholelithiasis. Patients with cholelithiasis typically present with pain in the right-upper quadrant of the abdomen with the associated symptoms of nausea and vomiting, especially after a fatty meal. The physician can confirm the diagnosis of cholelithiasis with an abdominal ultrasound that shows the ultrasonic shadows of the stones in the gallbladder.

The diagnosis of choledocholithiasis is suggested when the liver function blood test shows an elevation in bilirubin and serum transaminases. Other indicators include raised indicators of ampulla of vater (pancreatic duct obstruction) such as lipases and amylases. In prolonged cases the INR may change due to a decrease in vitamin K absorption. (It is the decreased bile flow which reduces fat breakdown and therefore absorption of fat soluable vitamins). The diagnosis is confirmed with either an Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), an ERCP, or an intraoperative cholangiogram. If the patient must have the gallbladder removed for gallstones, the surgeon may choose to proceed with the surgery, and obtain a cholangiogram during the surgery. If the cholangiogram shows a stone in the bile duct, the surgeon may attempt to treat the problem by flushing the stone into the intestine or retrieve the stone back through the cystic duct.

On a different pathway, the physician may choose to proceed with ERCP before surgery. The benefit of ERCP is that it can be utilized not just to diagnose, but also to treat the problem. During ERCP the endoscopist may surgically widen the opening into the bile duct and remove the stone through that opening. ERCP, however, is an invasive procedure and has its own potential complications. Thus, if the suspicion is low, the physician may choose to confirm the diagnosis with MRCP, a non-invasive imaging technique, before proceeding with ERCP or surgery.

Treatment

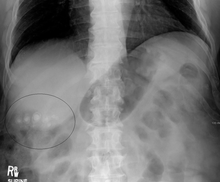

Fluoroscopic image taken during ERCP and duodenoscope assisted cholangiopancreatoscopy (DACP). Multiple gallstones are present in the gallbladder and cystic duct. The common bile duct and pancreatic duct appear to be patent.

Fluoroscopic image taken during ERCP and duodenoscope assisted cholangiopancreatoscopy (DACP). Multiple gallstones are present in the gallbladder and cystic duct. The common bile duct and pancreatic duct appear to be patent.

Treatment involves removing the stone using ERCP. Typically, the gallbladder is then removed, an operation called cholecystectomy, to prevent a future occurrence of common bile duct obstruction or other complications.[19]

In other animals

Gallstones are a valuable by-product of meat processing, fetching up to US$10–per–gram in their use as a purported antipyretic and antidote in the folk remedies of some cultures, in particular, in China. The finest gallstones tend to be sourced from old dairy cows, which are called (yellow thing of oxen) in Chinese. Those obtained from dogs, called Gou-Bao (treasure of dogs) in Chinese, are also used today. Much as in the manner of diamond mines, slaughterhouses carefully scrutinize offal department workers for gallstone theft.[20]

See also

References

- ^ Gallstones - Cholelithiasis; Gallbladder attack; Biliary colic; Gallstone attack; Bile calculus; Biliary calculus Last reviewed: July 6, 2009. Reviewed by: George F. Longstreth. Also reviewed by David Zieve

- ^ Channa, Naseem A.; Khand, Fateh D.; Khand, Tayab U.; Leghari, Mhhammad H.; Memon, Allah N. (2007). "Analysis of human gallstones by Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR)". Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences 23 (4): 546–50. ISSN 1682-024X. http://pjms.com.pk/issues/julsep07/article/article15.html. Retrieved 2010-11-06.

- ^ a b c Kim IS, Myung SJ, Lee SS, Lee SK, Kim MH (2003). "Classification and nomenclature of gallstones revisited". Yonsei Medical Journal 44 (4): 561–70. ISSN 0513-5796. PMID 12950109. http://www.eymj.org/Synapse/Data/PDFData/0069YMJ/ymj-44-561.pdf. Retrieved 2010-11-06.

- ^ a b c d National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (2007). "Gallstones". Bethesda, Maryland: National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse, National Institutes of Health, United States Department of Health and Human Services. http://digestive.niddk.nih.gov/ddiseases/pubs/gallstones/Gallstones.pdf. Retrieved 2010-11-06.

- ^ Heuman DM, Mihas AA, Allen J (2010). "Cholelithiasis". Omaha, Nebraska: Medscape (WebMD). http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/175667-overview. Retrieved 2010-11-06.

- ^ National Library of Medicine (2010). "Gallstones". Bethesda, Maryland: United States National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health, United States Department of Health and Human Services. http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/000273.htm. Retrieved 2010-11-06.

- ^ Roizen MF and Oz MC, Gut Feelings: Your Digestive System, pp. 175–206 in Roizen and Oz (2005)

- ^ Koppisetti, Sreedevi; Jenigiri, Bharat; Terron, M. Pilar; Tengattini, Sandra; Tamura, Hiroshi; Flores, Luis J.; Tan, Dun-Xian; Reiter, Russel J. (2008). "Reactive Oxygen Species and the Hypomotility of the Gall Bladder as Targets for the Treatment of Gallstones with Melatonin: A Review". Digestive Diseases and Sciences 53 (10): 2592–603. doi:10.1007/s10620-007-0195-5. PMID 18338264.

- ^ Ortega RM, Fernández-Azuela M, Encinas-Sotillos A, Andrés P, López-Sobaler AM (1997). "Differences in diet and food habits between patients with gallstones and controls". Journal of the American College of Nutrition 16 (1): 88–95. PMID 9013440. http://www.jacn.org/cgi/content/abstract/16/1/88. Retrieved 2010-11-06.

- ^ Misciagna, Giovanni; Leoci, Claudio; Guerra, Vito; Chiloiro, Marisa; Elba, Silvana; Petruzzi, José; Mossa, Ascanio; Noviello, Maria R. et al. (1996). "Epidemiology of cholelithiasis in southern Italy. Part II". European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology 8: 585–93. doi:10.1097/00042737-199606000-00017.

- ^ Trotman, Bruce W.; Bernstein, Seldon E.; Bove, Kevin E.; Wirt, Gary D. (1980). "Studies on the Pathogenesis of Pigment Gallstones in Hemolytic Anemia". Journal of Clinical Investigation 65 (6): 1301–8. doi:10.1172/JCI109793. PMC 371467. PMID 7410545. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=371467.

- ^ Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders: Cutaneous Porphyrias, pp. 63–220 in Beers, Porter and Jones (2006)

- ^ Thunell S (2008). "Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders: Cutaneous Porphyrias". Whitehouse Station, New Jersey: Merck Sharp & Dohme Corporation. http://www.merck.com/mmpe/sec12/ch155/ch155c.html?qt=Erythropoietic%20Protoporphyria&alt=sh#sec12-ch155-ch155c-635. Retrieved 2010-11-07.

- ^ M. A. Cahan; L. Balduf, K. Colton, B. Palacioz, W. McCartney and T. M. Farrell. "Proton pump inhibitors reduce gallbladder function". Surgical Endoscopy 20 (9): 1364–1367. doi:10.1007/s00464-005-0247-x. PMID 18481495. http://www.springerlink.com/content/p4qt7lx3j53g2813/.

- ^ a b National Health Service (2010). "Gallstones — Treatment". NHS Choices: Health A-Z - Conditions and treatments. London: National Health Service. http://www.nhs.uk/conditions/gallstones/pages/treatment.aspx. Retrieved 2010-11-06.

- ^ Jensen (2010). "Postcholecystectomy syndrome". Omaha, Nebraska: Medscape (WebMD). http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/192761-overview. Retrieved 2011-1-20.

- ^ Marks, Janet; Shuster, Sam; Watson, A. J. (1966). "Small-bowel changes in dermatitis herpetiformis". The Lancet 288 (7476): 1280–2. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(66)91692-8. PMID 4163419.

- ^ Keus, Frederik; de Jong, Jeroen; Gooszen, H G; Laarhoven, C JHM; Keus, Frederik (2006). "Laparoscopic versus open cholecystectomy for patients with symptomatic cholecystolithiasis". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (4): CD006231. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006231. PMID 17054285.

- ^ Vivian McAlister, Eric Davenport, and Elizabeth Renouf. Cholecystectomy Deferral in Patients with Endoscopic Sphincterotomy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.4 (2007): CD006233. Available at: [1]

- ^ "Interview with Darren Wise. Transcrip". Omaha, Nebraska: Medscape (WebMD). http://sgp1.paddington.ninemsn.com.au/sunday/cover_stories/transcript_785.asp. Retrieved 2010-11-06.

- Beers, MH; Porter, RS; Jones, TV, eds (2006). Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy (18th ed.). Whitehouse Station, New Jersey: Merck Sharp & Dohme Corporation. ISBN 9780911910186.

External links

- Public domain NIH/NIDDK e-pub on gallstones

- MedlinePlus Encyclopedia Gallbladder removal

- 5-Minute Clinical Consult Cholelithiasis

- Gall bladder surgery video

Categories:- Disorders of gallbladder, biliary tract and pancreas

- Hepatology

- Abdominal pain

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.