- Pneumonia

-

For other uses, see Pneumonia (disambiguation).

Pneumonia Classification and external resources

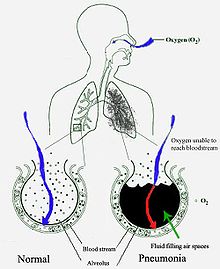

A chest X-ray showing a very prominent wedge-shaped bacterial pneumonia in the right lung.ICD-10 J12, J13, J14, J15, J16, J17, J18, P23 ICD-9 480-486, 770.0 DiseasesDB 10166 MedlinePlus 000145 eMedicine topic list MeSH D011014 Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung—especially affecting the microscopic air sacs (alveoli)—associated with fever, chest symptoms, and a lack of air space (consolidation) on a chest X-ray.[1][2] Pneumonia is typically caused by an infection but there are a number of other causes.[1] Infectious agents include: bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites.[3]

Typical symptoms include cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing.[4] Diagnostic tools include x-rays and examination of the sputum. Vaccines to prevent certain types of pneumonia are available. Treatment depends on the underlying cause with presumed bacterial pneumonia being treated with antibiotics.

Although pneumonia was regarded by William Osler in the 19th century as "the captain of the men of death", the advent of antibiotic therapy and vaccines in the 20th century have seen radical improvements in survival outcomes. Nevertheless, in the third world, and among the very old, the very young and the chronically ill, pneumonia remains a leading cause of death.[5]

Contents

Classification

Pneumonitis refers to lung inflammation; pneumonia refers to pneumonitis, usually due to infection but sometimes non infectious, that has the additional feature of pulmonary consolidation.[6] Pneumonia can be classified in several ways. It is most commonly classified by where or how it was acquired (community-acquired, aspiration, healthcare-associated, hospital-acquired, and ventilator-associated pneumonia),[7] but may also be classified by the area of lung affected (lobar pneumonia, bronchial pneumonia and acute interstitial pneumonia),[7] or by the causative organism.[8] Pneumonia in children may additionally be classified based on signs and symptoms as non-severe, severe, or very severe.[9]

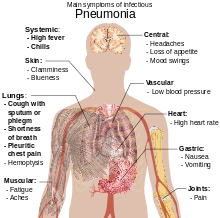

Signs and symptoms

People with infectious pneumonia often have a productive cough, fever accompanied by shaking chills, shortness of breath, sharp or stabbing chest pain during deep breaths, confusion, and an increased respiratory rate.[10] In the elderly, confusion may be the most prominent symptom.[10] The typical symptoms in children under five are fever, cough, and fast or difficult breathing.[11] Fever, however, is not very specific, as it occurs in many other common illnesses, and may be absent in those with severe disease or malnutrition. Additionally, a cough is frequently absent in children less than 2 months old.[11] More severe symptoms may include: central cyanosis, decreased thirst, convulsions, persistent vomiting, or a decreased level of consciousness.[11]

Symptoms frequency in pneumonia[12] Symptom Frequency Cough 79–91% Fatigue 90% Fever 71–75% Shortness of breath 67–75% Sputum 60–65% Chest pain 39–49% Some causes of pneumonia are associated with classic, but non-specific, clinical characteristics. Pneumonia caused by Legionella may occur with abdominal pain, diarrhea, or confusion,[13] while pneumonia caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae is associated with rusty colored sputum,[14] and pneumonia caused by Klebsiella may have bloody sputum often described as "currant jelly".[12]

Physical examination may sometimes reveal low blood pressure, a high heart rate, or a low oxygen saturation. Examination of the chest may be normal, but may show decreased chest expansion on the affected side. Harsh breath sounds from the larger airways that are transmitted through the inflamed lung are termed bronchial breathing, and are heard on auscultation with a stethoscope. Rales (or crackles) may be heard over the affected area during inspiration. Percussion may be dulled over the affected lung, and increased, rather than decreased, vocal resonance distinguishes pneumonia from a pleural effusion.[10] Struggling to breathe, confusion, and blue-tinged skin are signs of a medical emergency.

Cause

Pneumonia is primarily due to infections, with less common causes including irritants and the unknown. Although more than one hundred strains of micro organisms can cause pneumonia, only a few are responsible for most cases. The most common types of infectious are viruses and bacteria with it being less commonly due to fungi or parasites. Mixed infections with both viruses and bacterial may occur in up to 45% of infections in children and 15% of infections in adults.[15] A causative agent is not isolated in approximately half of cases despite careful testing.[16] The term pneumonia is sometimes more broadly applied to inflammation of the lung (for example caused by autoimmune disease, chemical burns or drug reactions), however this is more accurately referred to as pneumonitis.[17][18]

Bacteria

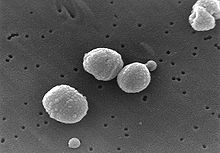

The bacterium Streptococcus pneumoniae, a common cause of pneumonia, imaged by an electron microscope

The bacterium Streptococcus pneumoniae, a common cause of pneumonia, imaged by an electron microscope

Bacteria are the most common cause of community acquired pneumonia, with Streptococcus pneumoniae isolated in nearly 50% of cases.[19][7] Other commonly isolated bacteria include: Haemophilus influenzae in 20%, Chlamydophila pneumoniae in 13%, Mycoplasma pneumoniae in 3%,[7], Staphylococcus aureus, Moraxella catarrhalis, Legionella pneumophila and gram-negative bacilli.[16]

Risk factors for infection depend on the organism involved.[16] Alcoholism is associated with Streptococcus pneumoniae, anaerobic organisms, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis, smoking is associated with Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, and Legionella pneumophila, exposure to bird with Chlamydia psittaci, farm animals with Coxiella burnetti, aspiration of stomach contents with anaerobes, and cystic fibrosis with Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus.[16] Streptococcus pneumoniae is more common in the winter.[16]

Viruses

In adults viruses account for approximately a third of pneumonia cases.[15] Commonly implicated agents include: rhinoviruses,[15]coronaviruses,[15] influenza virus,[20] respiratory syncytial virus (RSV),[20] adenovirus,[20] and parainfluenza.[20] Herpes simplex virus is a rare cause of pneumonia, except in newborns. People with weakened immune systems are at increased risk of pneumonia caused by cytomegalovirus (CMV).

Fungi

Fungal pneumonia is uncommon,[16] but it may occur in individuals with weakened immune systems due to AIDS, immunosuppressive drugs, or other medical problems. The pathophysiology of pneumonia caused by fungi is similar to that of bacterial pneumonia. Fungal pneumonia is most often caused by Histoplasma capsulatum, blastomyces, Cryptococcus neoformans, Pneumocystis jiroveci, and Coccidioides immitis. Histoplasmosis is most common in the Mississippi River basin, and coccidioidomycosis is most common in the southwestern United States.[16]

Parasites

A variety of parasites can affect the lungs. These parasites typically enter the body through the skin or the mouth. Once inside the body, they travel to the lungs, usually through the blood. In parasitic pneumonia, as with other kinds of pneumonia, a combination of cellular destruction and immune response causes disruption of oxygen transportation. One type of white blood cell, the eosinophil, responds vigorously to parasite infection. Eosinophils in the lungs can lead to eosinophilic pneumonia, thus complicating the underlying parasitic pneumonia. The most common parasites causing pneumonia are Toxoplasma gondii, Strongyloides stercoralis, and Ascariasis.

Idiopathic

Idiopathic interstitial pneumonia or noninfectious pneumonia[21] are a class of diffuse lung diseases. They include: diffuse alveolar damage, organizing pneumonia, nonspecific interstitial pneumonia, lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia, desquamative interstitial pneumonia, respiratory bronchiolitis interstitial lung disease, and usual interstitial pneumonia.[22]

Pathophysiology

Pneumonia frequently starts as a upper respiratory tract infection that moves into the lower respiratory tract.[23]

Viral

Viruses invade cells in order to reproduce. Typically, a virus reaches the lungs when airborne droplets are inhaled through the mouth or nose. Once in the lungs, the virus invades the cells lining the airways and alveoli. This invasion often leads to cell death, either from damage to the cell by the virus, or from a protective process called apoptosis in which the infected cell destroys itself before it can be used as a conduit for virus reproduction. When the immune system responds to the viral infection, even more lung damage occurs. White blood cells, mainly lymphocytes, activate certain chemical cytokines which allow fluid to leak into the alveoli. This combination of cell destruction and fluid-filled alveoli interrupts the normal transportation of oxygen into the bloodstream.

As well as damaging the lungs, many viruses affect other organs and thus disrupt many body functions. Viruses can also make the body more susceptible to other bacterial infections; in this way bacterial pneumonia can arise as a co-morbid condition.[20]

Bacterial

Bacteria typically enter the lung when airborne droplets are inhaled, but can also reach the lung through the bloodstream when there is an infection in another part of the body. Many bacteria live in parts of the upper respiratory tract, such as the nose, mouth and sinuses, and can easily be inhaled into the alveoli. Once inside, bacteria may invade the spaces between cells and between alveoli through connecting pores. This invasion triggers the immune system to send neutrophils, a type of defensive white blood cell, to the lungs. The neutrophils engulf and kill the offending organisms, and also release cytokines, causing a general activation of the immune system. This leads to the fever, chills, and fatigue common in bacterial and fungal pneumonia. The neutrophils, bacteria, and fluid from surrounding blood vessels fill the alveoli and interrupt normal oxygen transportation.

Diagnosis

Pneumonia is typically diagnosed based on a combination of physical signs and a chest X-ray.[24] Confirming the underlying cause can be difficult, however, with no definitive test able to distinguish between bacterial and not-bacterial origin.[15][24] The World Health Organization has defined pneumonia in children clinically based on a either a cough or difficulty breathing and a rapid respiratory rate, chest indrawing, or a decreased level of consciousness.[25] A rapid respiratory rate is defined as greater than 60 breaths per minute in children under 2 months old, 50 breaths per minute in children two months to one year old, or greater than 40 breaths per minute in children one to five years old.[25] In children, an increased respiratory rate and lower chest indrawing are more sensitive than hearing chest crackles with a stethoscope.[11]

In adults investigations are generally not needed in mild cases[26] as if all vital signs and auscultation are normal the risk of pneumonia is very low.[27]In those requiring admission to a hospital, pulse oximetry, chest radiography, and blood tests including a complete blood count, serum electrolytes, C-reactive protein, and possibly liver function tests are recommended.[26] The diagnosis of influenza-like illness can be made based on presenting signs and symptoms however verification of an influenza infection requires testing.[28] Thus treatment is frequently based on the presence of influenza in the community or a rapid influenza test.[28]

Imaging

A chest radiograph is frequently used in diagnosis.[11] In people with mild disease imaging is only needed in those with potential complications, those who have not improved with treatment, or those in which the cause in uncertain.[11][26] If a person is sufficiently sick to require hospitalization, a chest radiograph is recommended.[26] Findings do not always correlate with severity of disease and do not reliably distinguish between bacterial versus viral infection.[11]

X-ray signs of bacterial community acquired pneumonia classically show lung consolidation of one lung segmental lobe.[7] However, radiographic findings may be variable, especially in other types of pneumonia.[7] Aspiration pneumonia may present with bilateral opacities primarily in the bases of the lungs and on the right side.[7] Radiographs of viral pneumonia cases may appear normal, hyper-inflated, have bilateral patchy areas, or present similar to bacterial pneumonia with lobar consolidation.[7] A CT scan can give additional information in indeterminate cases.[7]

Microbiology

For people managed in the community figuring out the causative agent is not cost effective, and typically does not alter management.[11] For those who do not respond to treatment, sputum culture should be considered, and culture for Mycobacterium tuberculosis should be carried out in those with a chronic productive cough.[26] Testing for other specific organisms may be recommended during outbreaks, for public health reasons.[26] In those who are hospitalized for severe disease both sputum and blood cultures are recommended.[26] Viral infections can be confirmed via detection of either the virus or its antigens with culture or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) among other techniques.[15] With routine microbiological testing a causative agent is determined in only 15% of cases.[10]

Differential diagnosis

Several diseases can present similar to pneumonia, including: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, pulmonary edema, bronchiectasis, lung cancer and pulmonary emboli.[10] Unlike pneumonia, asthma and COPD typically present with wheezing, pulmonary edema presents with an abnormal electrocardiogram, cancer and bronchiectasis present with a cough of longer duration, and pulmonary emboli presents with acute onset sharp chest pain and shortness of breath.[10]

Prevention

Prevention includes vaccination, environmental measures, and appropriately treating other diseases.[11]

Vaccination

Vaccination is effective for preventing certain bacterial and viral pneumonias in both children and adults.

Influenza vaccines are modestly effective against influenza A and B.[15][29] The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that everyone 6 months and older get yearly vaccination.[30] When an influenza outbreak is occurring, medications such as amantadine, rimantadine, zanamivir, and oseltamivir can help prevent influenza.[31][32]

Vaccinations against Haemophilus influenzae and Streptococcus pneumoniae have good evidence to support their use.[23] Vaccinating children against Streptococcus pneumoniae has also led to a decreased incidence of these infections in adults, because many adults acquire infections from children. A vaccine against Streptococcus pneumoniae is also available for adults, and has been found to decrease the risk of invasive pneumococcal disease.[33]

Environmental

Reducing indoor air pollution is recommended[11] as is smoking cessation.[26]

Other

Appropriately treating underlying illnesses (such as AIDS) can decrease a person's risk of pneumonia.

There are several ways to prevent pneumonia in newborn infants. Testing pregnant women for Group B Streptococcus and Chlamydia trachomatis, and giving antibiotic treatment, if needed, reduces pneumonia in infants. Suctioning the mouth and throat of infants with meconium-stained amniotic fluid decreases the rate of aspiration pneumonia.

Management

CURB-65 Symptom Points Confusion 1 Urea>7mmol/l 1 Respiratory rate>30 1 SBP<90mmHg, DBP<60mmHg 1 Age>=65 1 Typically, oral antibiotics, rest, simple analgesics, and fluids are sufficient for complete resolution.[26] However, those with other medical conditions, the elderly, or those with significant trouble breathing may require more advanced care. If the symptoms worsen, the pneumonia does not improve with home treatment, or complications occur, hospitalization may be required.[26] Worldwide, approximately 7–13% of cases in children result in hospitalization[11] while in the developed world between 22–42% of adults with community acquired pneumonia are admitted.[26] The CURB-65 score is useful for determining the need for admission in adults.[26] If the score is 0 or 1 people can typically be managed at home, if it is 2 a short hospital stay or close follow up is needed, if it is 3–5 hospitalization is recommended.[26] In children those with respiratory distress or oxygen saturation's of less than 90% should be hospitalized.[34] The utility of chest physiotherapy in pneumonia has not yet been determined.[35] Over the counter cough medicine has not been found to be effective.[36]

Bacterial

Antibiotics improve outcomes in those with bacterial pneumonia.[37] Initially antibiotic choice depends on the characteristics of the person affected, such as age, underlying health, and the location the infection was acquired. In the UK empiric treatment with amoxicillin is recommended first line for community-acquired pneumonia with doxycycline or clarithromycin as alternatives.[26] In North America, where the "atypical" forms of community-acquired pneumonia are more common, macrolides (such as azithromycin), and doxycycline have displaced amoxicillin as first-line outpatient treatment in adults.[19][38] In children with mild or moderate symptoms amoxicillin is still the first line.[34] The use of fluoroquinolones in uncomplicated cases is discouraged due to concerns of side effects and resistance.[19] The duration of treatment has traditionally been seven to ten days, but there is increasing evidence that short courses (three to five days) are similarly effective.[39] Antibiotics recommended for hospital-acquired pneumonia include third- and fourth-generation cephalosporins, carbapenems, fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, and vancomycin.[40] These antibiotics are often given intravenously, and may be used in combination.

Viral

Neuraminidase inhibitors may be used to treat viral pneumonia caused by influenza viruses (influenza A and influenza B).[15] No specific antiviral medications are recommended for other types of community acquired viral pneumonias including SARS coronavirus, adenovirus, hantavirus, and parainfluenza virus.[15] Influenza A may be treated with rimantadine or amantadine, while influenza A or B may be treated with oseltamivir, zanamivir or peramivir.[15] These are of most benefit if they are started within 48 hours of the onset of symptoms.[15] Many strains of H5N1 influenza A, also known as avian influenza or "bird flu," have shown resistance to rimantadine and amantadine.[15] The use of antibiotics in viral pneumonia is recommended by some experts as it is impossible to rule out a complicating bacterial infection.[15] The British Thoracic Society recommends that antibiotics be withheld in those with mild disease.[15] The use of corticosteroids is controversial.[15]

Aspiration

Aspiration pneumonitis is generally treated conservatively with antibiotics only indicated for aspiration pneumonia.[41] The choice of antibiotic will depend on several factors, including the suspected causative organism and whether pneumonia was acquired in the community or developed in a hospital setting. Common options include clindamycin, a combination of a beta-lactam antibiotic and metronidazole, or an aminoglycoside.[42] Corticosteroids are commonly used in aspiration pneumonia, but there is no evidence to support their effectiveness.[42]

Prognosis

With treatment, most types of bacterial pneumonia can be cleared within two to four weeks[43] and mortality is very low.[15] Viral pneumonia may last longer, and mycoplasmal pneumonia may take four to six weeks to resolve completely.[43] The eventual outcome of an episode of pneumonia depends on how ill the person is when he or she was first diagnosed.[43] Before the advent of antibiotics mortality was typically 30% for hospitalized patients.[16]

In the United States, about 5% of those diagnosed with pneumococcal pneumonia will die. In cases where the pneumonia progresses to blood infection, just over 20% will die.[44]

The death rate (or mortality) also depends on the underlying cause of the pneumonia. Pneumonia caused by Mycoplasma, for instance, is associated with lower mortality. However, about half of the people who develop methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) pneumonia while on a ventilator will die.[45] In regions of the world without advanced health care systems, pneumonia is even more deadly. Limited access to clinics and hospitals, limited access to x-rays, limited antibiotic choices, and inability to diagnose and treat underlying conditions inevitably lead to higher rates of death from pneumonia. For these reasons, the majority of deaths in children under five due to pneumococcal disease occur in developing countries.[46]

Adenovirus can cause severe necrotizing pneumonia in which all or part of a lung has increased translucency radiographically, which is called Swyer-James Syndrome.[47] Severe adenovirus pneumonia also may result in bronchiolitis obliterans, a subacute inflammatory process in which the small airways are replaced by scar tissue, resulting in a reduction in lung volume and lung compliance.[47] Sometimes pneumonia can lead to additional complications. Complications are more frequently associated with bacterial pneumonia than with viral pneumonia. The most important complications include respiratory and circulatory failure and pleural effusions, empyema or abscesses.

Clinical prediction rules

Clinical prediction rules have been developed to more objectively prognosticate outcomes in pneumonia. Although these rules are often used in deciding whether or not to hospitalize the person, they were derived simply to inform on prognosis; neither index was designed or tested as guide to determine whether the person would benefit by hospital admission.

- Pneumonia severity index (or PORT Score)[48] – online calculator

- CURB-65 score, which takes into account the severity of symptoms, any underlying diseases, and age[49] – online calculator

Pleural effusion, empyema, and abscess

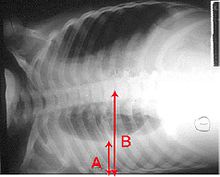

A pleural effusion as seen on chest x-ray. The A arrow indicates fluid layering in the right chest. The B arrow indicates the width of the right lung. The volume of the lung is reduced because of the collection of fluid around the lung.

A pleural effusion as seen on chest x-ray. The A arrow indicates fluid layering in the right chest. The B arrow indicates the width of the right lung. The volume of the lung is reduced because of the collection of fluid around the lung.

In pneumonia, a collection of fluid (pleural effusion) often forms in the space that surrounds the lung (the pleural cavity). Occasionally, microorganisms will infect this fluid, causing what is called an empyema. To distinguish an empyema from the more common simple parapneumonic effusion, the fluid is collected with a needle (thoracentesis), and examined. If this shows evidence of empyema, complete drainage of the fluid may be necessary, often requiring a chest tube. In severe cases of empyema, surgery may be needed. If the infected fluid is not drained, the infection may persist, because antibiotics do not penetrate well into the pleural cavity. If the fluid is sterile, it need only be drained if it is causing symptoms or remains unresolved.

Rarely, bacteria in the lung will form a pocket of infected fluid called a lung abscess. Lung abscesses can usually be seen with a chest x-ray or chest CT scan. Abscesses typically occur in aspiration pneumonia, and often contain several types of bacteria. Antibiotics are usually adequate to treat a lung abscess, but sometimes the abscess must be drained by a surgeon or radiologist.

Respiratory and circulatory failure

Because pneumonia affects the lungs, people with pneumonia often have difficulty breathing, sometimes to the point where mechanical assistance is required. Non-invasive breathing assistance may be helpful, such as with a bi-level positive airway pressure machine. In other cases, placement of an endotracheal tube (breathing tube) may be necessary, and a ventilator may be used to help the person breathe.

Pneumonia can also cause respiratory failure by triggering acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), which results from a combination of infection and inflammatory response. The lungs quickly fill with fluid and become very stiff. This stiffness, combined with severe difficulties extracting oxygen due to the alveolar fluid, creates a need for mechanical ventilation.

Sepsis and septic shock are potential complications of pneumonia. Sepsis occurs when microorganisms enter the bloodstream and the immune system responds by secreting cytokines. Sepsis most often occurs with bacterial pneumonia; Streptococcus pneumoniae is the most common cause. Individuals with sepsis or septic shock need hospitalization in an intensive care unit. They often require intravenous fluids and medications to help keep their blood pressure up. Sepsis can cause liver, kidney, and heart damage, among other problems, and it is often fatal.

Epidemiology

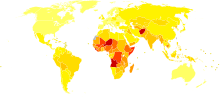

Main article: Epidemiology of pneumonia Age-standardized death from lower respiratory tract infections per 100,000 inhabitants in 2004.[50]

Age-standardized death from lower respiratory tract infections per 100,000 inhabitants in 2004.[50] no data<100100-700700-14001400-21002100-28002800-35003500-42004200-49004900-56005600-63006300-7000>7000

no data<100100-700700-14001400-21002100-28002800-35003500-42004200-49004900-56005600-63006300-7000>7000Pneumonia is a common illness affecting approximately 450 million people a year and occurring in all parts of the world.[15] It is a major cause of death among all age groups resulting in 4 million deaths (7% of the world's yearly total).[37][15] Rates are greatest in children less than five, and adults older than 75 years of age.[15] It occurs about five times more frequently in the developing world versus the developed world.[15] Viral pneumonia accounts for about 200 million cases.[15]

Children

In 2008 pneumonia occurred in approximately 156 million children (151 million in the developing world and 5 million in the developed world).[15] It resulted in 1.6 million deaths, or 28–34% of all deaths in those under five years of age, of which 95% occurred in the developing world.[15][11] Countries with the greatest burden of disease include: India (43 million), China (21 million) and Pakistan (10 million).[51] It is the leading cause of death among children in low income countries.[37][15] Many of these deaths occur in the newborn period. The World Health Organization estimates that one in three newborn infant deaths are due to pneumonia.[52] Approximately half of these deaths are theoretically preventable, as they are caused by the bacteria for which an effective vaccine is available.[53]

History

Pneumonia has been a common disease throughout human history.[54] The symptoms were described by Hippocrates (c. 460 BC – 370 BC):[54] "Peripneumonia, and pleuritic affections, are to be thus observed: If the fever be acute, and if there be pains on either side, or in both, and if expiration be if cough be present, and the sputa expectorated be of a blond or livid color, or likewise thin, frothy, and florid, or having any other character different from the common... When pneumonia is at its height, the case is beyond remedy if he is not purged, and it is bad if he has dyspnoea, and urine that is thin and acrid, and if sweats come out about the neck and head, for such sweats are bad, as proceeding from the suffocation, rales, and the violence of the disease which is obtaining the upper hand."[55] However, Hippocrates referred to pneumonia as a disease "named by the ancients." He also reported the results of surgical drainage of empyemas. Maimonides (1135–1204 AD) observed "The basic symptoms which occur in pneumonia and which are never lacking are as follows: acute fever, sticking [pleuritic] pain in the side, short rapid breaths, serrated pulse and cough."[56] This clinical description is quite similar to those found in modern textbooks, and it reflected the extent of medical knowledge through the Middle Ages into the 19th century.

Bacteria were first seen in the airways of individuals who died from pneumonia by Edwin Klebs in 1875.[57] Initial work identifying the two common bacterial causes Streptococcus pneumoniae and Klebsiella pneumoniae was performed by Carl Friedländer[58] and Albert Fränkel[59] in 1882 and 1884, respectively. Friedländer's initial work introduced the Gram stain, a fundamental laboratory test still used today to identify and categorize bacteria. Christian Gram's paper describing the procedure in 1884 helped differentiate the two different bacteria, and showed that pneumonia could be caused by more than one microorganism.[60]

Sir William Osler, known as "the father of modern medicine," appreciated the death and disability cause by pneumonia, describing it as the "captain of the men of death" in 1918, as it had overtaken tuberculosis as one of the leading causes of death in this time. This phrase was originally coined by John Bunyan in reference to "consumption" (tuberculosis).[61][62] Osler also described pneumonia as "the old man's friend" as death was often quick and painless when there was many slower more painful ways to die.[16]

Several developments in the 1900s improved the outcome for those with pneumonia. With the advent of penicillin and other antibiotics, modern surgical techniques, and intensive care in the twentieth century, mortality from pneumonia, which had approached 30%, dropped precipitously in the developed world. Vaccination of infants against Haemophilus influenzae type B began in 1988 and led to a dramatic decline in cases shortly thereafter.[63] Vaccination against Streptococcus pneumoniae in adults began in 1977, and in children in 2000, resulting in a similar decline.[64]

Society and culture

Because of the combination of a very high burden of disease in developing countries and a relatively low awareness of the disease in industrialized countries, the global health community has declared November 12 to be World Pneumonia Day, a day for concerned citizens and policy makers to take action against the disease.[65]

References

- ^ a b McLuckie, [editor] A. (2009). Respiratory disease and its management. New York: Springer. p. 51. ISBN 9781848820944.

- ^ Leach, Richard E. (2009). Acute and Critical Care Medicine at a Glance (2 ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 1-4051-6139-6. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=7u_wu5VCsVQC&pg=PT168. Retrieved 2011-04-21.

- ^ Jeffrey C. Pommerville (2010). Alcamo's Fundamentals of Microbiology (9 ed.). Sudbury, Mass: Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 323. ISBN 0-7637-6258-X. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=RJNQwQB8IxIC&pg=PA323.

- ^ Ashby, Bonnie; Turkington, Carol (2007). The encyclopedia of infectious diseases (3 ed.). New York: Facts on File. p. 242. ISBN 0-8160-6397-4. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=4Xlyaipv3dIC&pg=PA242. Retrieved 2011-04-21.

- ^ "Causes of death in neonates and children under five in the world (2004)". World Health Organization.. 2008. http://www.who.int/entity/child_adolescent_health/media/causes_death_u5_neonates_2004.pdf.

- ^ Stedman's medical dictionary. (28th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2006. ISBN 9780781764506.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Sharma, S; Maycher, B, Eschun, G (2007 May). "Radiological imaging in pneumonia: recent innovations". Current opinion in pulmonary medicine 13 (3): 159–69. doi:10.1097/MCP.0b013e3280f3bff4. PMID 17414122.

- ^ Dunn, L (2005 Jun 29-Jul 5). "Pneumonia: classification, diagnosis and nursing management". Nursing standard (Royal College of Nursing (Great Britain) : 1987) 19 (42): 50–4. PMID 16013205.

- ^ organization, World health (2005). Pocket book of hospital care for children : guidelines for the management of common illnesses with limited resources.. Geneva: World Health Organization. p. 72. ISBN 9789241546706. http://books.google.com/books?id=xbkbRG5XYxsC&pg=PA72.

- ^ a b c d e f Hoare Z; Lim WS (2006). "Pneumonia: update on diagnosis and management". BMJ 332 (7549): 1077–9. doi:10.1136/bmj.332.7549.1077. PMC 1458569. PMID 16675815. http://www.bmj.com/content/332/7549/1077.full.pdf.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Singh, V; Aneja, S (2011 Mar). "Pneumonia - management in the developing world". Paediatric respiratory reviews 12 (1): 52–9. doi:10.1016/j.prrv.2010.09.011. PMID 21172676.

- ^ a b Tintinalli, Judith E. (2010). Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide (Emergency Medicine (Tintinalli)). New York: McGraw-Hill Companies. pp. 480. ISBN 0-07-148480-9.

- ^ Darby, J; Buising, K (2008 Oct). "Could it be Legionella?". Australian family physician 37 (10): 812–5. PMID 19002299.

- ^ Ortqvist, A; Hedlund, J, Kalin, M (2005 Dec). "Streptococcus pneumoniae: epidemiology, risk factors, and clinical features.". Seminars in respiratory and critical care medicine 26 (6): 563–74. PMID 16388428.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Ruuskanen, O; Lahti, E, Jennings, LC, Murdoch, DR (2011 Apr 9). "Viral pneumonia". Lancet 377 (9773): 1264–75. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61459-6. PMID 21435708.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Ebby, Orin (Dec 2005). "Community-Acquired Pneumonia: From Common Pathogens To Emerging Resistance". Emergency Medicine Practice 7 (12). https://www.ebmedicine.net/topics.php?paction=showTopic&topic_id=118.

- ^ Lowe, J. F.; Stevens, Alan (2000). Pathology (2 ed.). St. Louis: Mosby. p. 197. ISBN 0-7234-3200-7. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=AfVxLi4QTZQC&pg=PA197.

- ^ Snydman, editors, Raleigh A. Bowden, Per Ljungman, David R. (2010). Transplant infections (3rd ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 187. ISBN 9781582558202. http://books.google.com/books?id=NWa4FJv-eBYC&pg=PA447.

- ^ a b c Anevlavis S; Bouros D (February 2010). "Community acquired bacterial pneumonia". Expert Opin Pharmacother 11 (3): 361–74. doi:10.1517/14656560903508770. PMID 20085502.

- ^ a b c d e Figueiredo LT (September 2009). "Viral pneumonia: epidemiological, clinical, pathophysiological and therapeutic aspects". J Bras Pneumol 35 (9): 899–906. PMID 19820817.

- ^ Clinical infectious diseases : a practical approach. New York, NY [u.a.]: Oxford Univ. Press. 1999. p. 833. ISBN 9780195081039. http://books.google.com/books?id=zvCOpighJggC&pg=PA833.

- ^ Diffuse parenchymal lung disease : ... 47 tables ([Online-Ausg.] ed.). Basel: Karger. 2007. p. 4. ISBN 9783805581530.

- ^ a b Ranganathan, SC; Sonnappa, S (2009 Feb). "Pneumonia and other respiratory infections.". Pediatric clinics of North America 56 (1): 135-56, xi. PMID 19135585.

- ^ a b Lynch, T; Bialy, L, Kellner, JD, Osmond, MH, Klassen, TP, Durec, T, Leicht, R, Johnson, DW (2010 Aug 6). Huicho, Luis. ed. "A systematic review on the diagnosis of pediatric bacterial pneumonia: when gold is bronze". PloS one 5 (8): e11989. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011989. PMC 2917358. PMID 20700510. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2917358.

- ^ a b Ezzati, edited by Majid; Lopez, Alan D., Rodgers, Anthony, Murray, Christopher J.L. (2004). Comparative quantification of health risks. Genève: Organisation mondiale de la santé. p. 70. ISBN 9789241580311. http://books.google.com/books?id=ACV1jEGx4AgC&pg=PA70.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Lim, WS; Baudouin, SV, George, RC, Hill, AT, Jamieson, C, Le Jeune, I, Macfarlane, JT, Read, RC, Roberts, HJ, Levy, ML, Wani, M, Woodhead, MA, Pneumonia Guidelines Committee of the BTS Standards of Care, Committee (2009 Oct). "BTS guidelines for the management of community acquired pneumonia in adults: update 2009". Thorax 64 Suppl 3: iii1–55. doi:10.1136/thx.2009.121434. PMID 19783532.

- ^ Saldías, F; Méndez, JI, Ramírez, D, Díaz, O (2007 Apr). "[Predictive value of history and physical examination for the diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia in adults: a literature review].". Revista medica de Chile 135 (4): 517–28. PMID 17554463.

- ^ a b Call, SA; Vollenweider, MA, Hornung, CA, Simel, DL, McKinney, WP (2005 Feb 23). "Does this patient have influenza?". JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 293 (8): 987–97. PMID 15728170.

- ^ Jefferson, T; Di Pietrantonj, C, Rivetti, A, Bawazeer, GA, Al-Ansary, LA, Ferroni, E (2010 Jul 7). Jefferson, Tom. ed. "Vaccines for preventing influenza in healthy adults". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (7): CD001269. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001269.pub4. PMID 20614424.

- ^ "Seasonal Influenza (Flu)". Center for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www.cdc.gov/flu/. Retrieved 29 June 2011.

- ^ Jefferson T; Deeks JJ, Demicheli V, Rivetti D, Rudin M (2004). Jefferson, Tom. ed. "Amantadine and rimantadine for preventing and treating influenza A in adults". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3): CD001169. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001169.pub2. PMID 15266442.

- ^ Hayden FG; Atmar RL, Schilling M, et al. (October 1999). "Use of the selective oral neuraminidase inhibitor oseltamivir to prevent influenza" (PDF). N. Engl. J. Med. 341 (18): 1336–43. doi:10.1056/NEJM199910283411802. PMID 10536125. http://www.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/NEJM199910283411802.

- ^ Moberley, SA; Holden, J, Tatham, DP, Andrews, RM (2008 Jan 23). Andrews, Ross M. ed. "Vaccines for preventing pneumococcal infection in adults". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (1): CD000422. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000422.pub2. PMID 18253977.

- ^ a b Bradley, JS; Byington, CL, Shah, SS, Alverson, B, Carter, ER, Harrison, C, Kaplan, SL, Mace, SE, McCracken GH, Jr, Moore, MR, St Peter, SD, Stockwell, JA, Swanson, JT (2011 Aug 31). "The Management of Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Infants and Children Older Than 3 Months of Age: Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America.". Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. PMID 21880587.

- ^ Yang, M; Yuping, Y, Yin, X, Wang, BY, Wu, T, Liu, GJ, Dong, BR (2010 Feb 17). "Chest physiotherapy for pneumonia in adults.". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (2): CD006338. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006338.pub2. PMID 20166082.

- ^ Chang CC; Cheng AC, Chang AB (2007). Chang, Christina C. ed. "Over-the-counter (OTC) medications to reduce cough as an adjunct to antibiotics for acute pneumonia in children and adults". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD006088. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006088.pub2. PMID 17943884.

- ^ a b c Kabra SK; Lodha R, Pandey RM (2010). Kabra, Sushil K. ed. "Antibiotics for community-acquired pneumonia in children". Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3 (3): CD004874. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004874.pub3. PMID 20238334.

- ^ Lutfiyya MN; Henley E, Chang LF, Reyburn SW (February 2006). "Diagnosis and treatment of community-acquired pneumonia". Am Fam Physician 73 (3): 442–50. PMID 16477891. http://www.aafp.org/afp/2006/0201/p442.pdf.

- ^ Scalera NM; File TM (April 2007). "How long should we treat community-acquired pneumonia?". Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 20 (2): 177–81. doi:10.1097/QCO.0b013e3280555072. PMID 17496577.

- ^ American Thoracic Society; Infectious Diseases Society of America (February 2005). "Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia". Am J Respir Crit Care Med 171 (4): 388–416. doi:10.1164/rccm.200405-644ST. PMID 15699079.

- ^ Marik, PE (2011 May). "Pulmonary aspiration syndromes.". Current opinion in pulmonary medicine 17 (3): 148–54. PMID 21311332.

- ^ a b O'Connor S (2003). "Aspiration pneumonia and pneumonitis". Australian Prescriber 26 (1): 14–7. http://www.australianprescriber.com/magazine/26/1/14/7.

- ^ a b c Pneumonia, Bacterial at eMedicine, specifically, "The chest radiograph usually clears within 4 weeks in patients younger than 50 years without underlying pulmonary disease". Symptoms are often resolved within 1–2 weeks,

- ^ Mufson, MA; RJ Stanek (1999-07-26). "Bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia in one American City: a 20-year longitudinal study, 1978–1997". Am J Med (Department of Medicine, Marshall University School of Medicine) 107 (1A): 34S–43S. doi:10.1016/S0002-9343(99)00098-4. PMID 10451007.

- ^ Combes A; Luyt CE, Fagon JY, et al. (October 2004). "Impact of methicillin resistance on outcome of Staphylococcus aureus ventilator-associated pneumonia". Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 170 (7): 786–92. doi:10.1164/rccm.200403-346OC. PMID 15242840.

- ^ World Health Organization. Acute Respiratory Infections: Streptococcus pneumoniae.

- ^ a b Kliegman, Robert; Richard M Kliegman (2006). Nelson essentials of pediatrics. St. Louis, Mo: Elsevier Saunders. ISBN 0-8089-2325-0.

- ^ Fine MJ; Auble TE, Yealy DM, et al. (January 1997). "A prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia" (PDF). N. Engl. J. Med. 336 (4): 243–50. doi:10.1056/NEJM199701233360402. PMID 8995086. http://www.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/NEJM199701233360402.

- ^ Lim WS; van der Eerden MM, Laing R, et al. (2003). "Defining community acquired pneumonia severity on presentation to hospital: an international derivation and validation study". Thorax 58 (5): 377–82. doi:10.1136/thorax.58.5.377. PMC 1746657. PMID 12728155. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1746657.

- ^ "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization (WHO). 2004. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/estimates_country/en/index.html. Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- ^ Rudan, I; Boschi-Pinto, C, Biloglav, Z, Mulholland, K, Campbell, H (2008 May). "Epidemiology and etiology of childhood pneumonia". Bulletin of the World Health Organization 86 (5): 408–16. doi:10.2471/BLT.07.048769. PMC 2647437. PMID 18545744. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2647437.

- ^ Garenne M; Ronsmans C, Campbell H (1992). "The magnitude of mortality from acute respiratory infections in children under 5 years in developing countries". World Health Stat Q 45 (2–3): 180–91. PMID 1462653.

- ^ WHO (1999). "Pneumococcal vaccines. WHO position paper". Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 74 (23): 177–83. PMID 10437429.

- ^ a b al.], Ralph D. Feigin ... [et (2003). Textbook of pediatric infectious diseases (5th ed.). Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders. p. 299. ISBN 9780721693293. http://books.google.com/books?id=G6k0tpPMRsIC&pg=PA299.

- ^ Hippocrates On Acute Diseases wikisource link

- ^ Maimonides, Fusul Musa ("Pirkei Moshe").

- ^ Klebs E (1875-12-10). "Beiträge zur Kenntniss der pathogenen Schistomyceten. VII Die Monadinen". Arch. Exptl. Pathol. Parmakol. 4 (5/6): 40–488.

- ^ Friedländer C (1882-02-04). "Über die Schizomyceten bei der acuten fibrösen Pneumonie". Virchow's Arch pathol. Anat. U. Physiol. 87 (2): 319–324. doi:10.1007/BF01880516.

- ^ Fraenkel A (1884-04-21). "Über die genuine Pneumonie, Verhandlungen des Congress für innere Medicin". Dritter Congress 3: 17–31.

- ^ Gram C (1884-03-15). "Über die isolierte Färbung der Schizomyceten in Schnitt- und Trocken-präparaten". Fortschr. Med 2 (6): 185–9.

- ^ al.], edited by J.F. Tomashefski, Jr ... [et (2008). Dail and Hammar's pulmonary pathology. (3. ed.). New York: Springer. p. 228. ISBN 9780387983950. http://books.google.com/books?id=j-eYLc1BA3oC&pg=PA228.

- ^ William Osler, Thomas McCrae (1920). The principles and practice of medicine: designed for the use of practitioners and students of medicine (9th ed.). D. Appleton. p. 78. "One of the most widespread and fatal of all acute diseases, pneumonia has become the "Captain of the Men of Death," to use the phrase applied by John Bunyan to consumption."

- ^ Adams WG; Deaver KA, Cochi SL, et al. (January 1993). "Decline of childhood Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib) disease in the Hib vaccine era". JAMA 269 (2): 221–6. doi:10.1001/jama.269.2.221. PMID 8417239.

- ^ Whitney CG; Farley MM, Hadler J, et al. (May 2003). "Decline in invasive pneumococcal disease after the introduction of protein-polysaccharide conjugate vaccine". N. Engl. J. Med. 348 (18): 1737–46. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa022823. PMID 12724479.

- ^ "World Pneumonia Day Official Website". World Pneumonia Day Official Website. Fiinex. http://worldpneumoniaday.org/. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

Pathology: Medical conditions and ICD code (Disease / Disorder / Illness, Syndrome / Sequence, Symptom / Sign, Injury, etc.) (A/B, 001–139) Infectious disease/Infection: Bacterial disease (G+, G-) · Virus disease · Parasitic disease (Protozoan infection, Helminthiasis, Ectoparasitic infestation) · Mycosis · Zoonosis(C/D,

140–239 &

279–289)(E, 240–278) (F, 290–319) (G, 320–359) (H, 360–389) (I, 390–459) (J, 460–519) (K, 520–579) Stomatognathic disease (Tooth disease) · Digestive disease (Esophageal, Stomach, Enteropathy, Liver, Pancreatic)(L, 680–709) (M, 710–739) (N, 580–629) Urologic disease (Nephropathy, Urinary bladder disease) · Male genital disease · Breast disease · Female genital disease(O, 630–679) (P, 760–779) (Q, 740–759) (R, 780–799) (S/T, 800–999) Pneumonia Infectious pneumonias Pneumonias caused by

infectious or noninfectious agentsNoninfectious pneumonia Chemical pneumoniaCategories:- Pneumonia

- Infectious diseases

- Respiratory and cardiovascular disorders specific to the perinatal period

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.