- Chlamydophila pneumoniae

-

Chlamydia pneumoniae Scientific classification Kingdom: Bacteria Phylum: Chlamydiae Order: Chlamydiales Family: Chlamydiaceae Genus: Chlamydophila Species: C. Pneumoniae Chlamydophila pneumoniae is a species of Chlamydophila, an obligate intracellular bacteria[1] that infects humans and is a major cause of pneumonia.

It was known as the TWAR (Taiwan Acute Respiratory) agent from the names of the two original isolates - Taiwan (TW-183) and an acute respiratory isolate designated AR-39.[2]

Until recently it was known as Chlamydia pneumoniae, and that name is used as an alternate in some sources.[3] In some cases, to avoid confusion, both names are given.[4]

C. pneumoniae has a complex life cycle and must infect another cell in order to reproduce; thus it is classified as an obligate intracellular pathogen. The full genome sequence for C. pneumoniae was published in 1999.

C. pneumoniae also infects and causes disease in Koalas, emerald tree boa (Corallus caninus), iguanas, chameleons, frogs, and turtles.

The first known case of infection with C. pneumoniae was a case of sinusitis in Taiwan.

This atypical bacterium commonly causes pharyngitis, bronchitis and atypical pneumonia[5] mainly in elderly and debilitated patients but in healthy adults also.[6]

Contents

Life cycle and method of infection

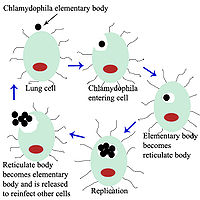

Chlamydophila pneumoniae is a small bacterium (0.2 to 1 micrometer) that undergoes several transformations during its life cycle. It exists as an elementary body (EB) in between hosts. The EB is not biologically active but is resistant to environmental stresses and can survive outside of a host for a limited time. The EB travels from an infected person to the lungs of a non-infected person in small droplets and is responsible for infection. Once in the lungs, the EB is taken up by cells in a pouch called an endosome by a process called phagocytosis. However, the EB is not destroyed by fusion with lysosomes as is typical for phagocytosed material. Instead, it transforms into a reticulate body and begins to replicate within the endosome. The reticulate bodies must utilize some of the host's cellular machinery to complete its replication. The reticulate bodies then convert back to elementary bodies and are released back into the lung, often after causing the death of the host cell. The EBs are thereafter able to infect new cells, either in the same organism or in a new host. Thus, the life cycle of C. pneumoniae is divided between the elementary body, which is able to infect new hosts but can not replicate, and the reticulate body ,which replicates but is not able to cause new infection.

Pneumonia

C. pneumoniae is a common cause of pneumonia around the world. C. pneumoniae is typically acquired by otherwise healthy people and is a form of community-acquired pneumonia. Because treatment and diagnosis are different from historically recognized causes such as Streptococcus pneumoniae, pneumonia caused by C. pneumoniae is categorized as an "atypical pneumonia."

Other illnesses

In addition to pneumonia, C. pneumoniae less commonly causes several other illnesses. Among these are meningoencephalitis (infection and inflammation of the brain and meninges), arthritis, myocarditis (inflammation of the heart), and Guillain-Barré syndrome.

Association with lung cancer

Multiple studies have studied whether there is an association between prior C. pneumoniae infection and lung cancer. One meta-analysis of studies looking at associating serological data showing prior C. pneumoniae infection in patients with and without lung cancer found results suggesting prior infection was associated with a small increased risk of developing lung cancer. The authors of this study suggested further research should be conducted using larger populations and more methodologically robust study design to confirm this result.[7]

Links with chronic diseases

There has been considerable research into the association between C. pneumoniae infection and atherosclerosis and coronary artery disease. Serological testing, direct pathologic analysis of plaques and in vitro testing suggest chronic infection with C. pneumoniae may be a risk factor for development of atherosclerotic plaques. C. pneumoniae infection increases adherence of macrophages to endothelial cells in vitro and ex vivo.[8] However, the current data does not define how often C. pneumoniae is found in atherosclerotic or normal vascular tissue nor does it allow for determining whether C. pneumoniae infection has a causative effect on atheroma formation or is merely an "innocent passenger" in these plaques. The largest trials that studied the use of antibiotics as a prevention for diseases associated with atherosclerosis such as heart attacks and strokes did not show any significant difference between antibiotics and placebo.[9]

C. pneumoniae has also been found in the cerebrospinal fluid of some patients diagnosed with multiple sclerosis.[10]

References

- ^ MeSH Chlamydophila+pneumoniae

- ^ http://pathmicro.med.sc.edu/mayer/chlamyd.htm

- ^ "www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov". http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/Browser/wwwtax.cgi?mode=Info&id=83558&lvl=3&lin=f&keep=1&srchmode=1&unlock. Retrieved 2009-01-27.

- ^ Appelt DM, Roupas MR, Way DS, et al. (2008). "Inhibition of apoptosis in neuronal cells infected with Chlamydophila (Chlamydia) pneumoniae". BMC Neurosci 9: 13. doi:10.1186/1471-2202-9-13. PMC 2266938. PMID 18218130. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2202/9/13.

- ^ Lang, B. R., Chlamydia pneumonia as a differential diagnosis? Follow-up to a case report on progressive pneumonitis in an adolescent, Patient Care, Sept. 15, 1991

- ^ Little, Linda, Elusive pneumonia strain frustrates many clinicians, Medical Tribune, p. 6, September 19, 1991

- ^ Zhan P, Suo LJ, Qian Q, et al. (March 2011). "Chlamydia pneumoniae infection and lung cancer risk: A meta-analysis". Eur. J. Cancer 47 (5): 742–7. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2010.11.003. PMID 21194924.

- ^ Takaoka N, Campbell LA, Lee A, Rosenfeld ME, Kuo CC (February 2008). "Chlamydia pneumoniae infection increases adherence of mouse macrophages to mouse endothelial cells in vitro and to aortas ex vivo.". Infect Immun. 76 (2): 510–4. doi:10.1128/IAI.01267-07. PMID 18070891.

- ^ Mussa FF, Chai H, Wang X, Yao Q, Lumsden AB, Chen C (June 2006). "Chlamydia pneumoniae and vascular disease: an update". J. Vasc. Surg. 43 (6): 1301–7. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2006.02.050. PMID 16765261.

- ^ Sriram S, Stratton CW, Yao S, et al. (1999). "Chlamydia pneumoniae infection of the central nervous system in multiple sclerosis". Ann. Neurol. 46 (1): 6–14. doi:10.1002/1531-8249(199907)46:1<6::AID-ANA4>3.0.CO;2-M. PMID 10401775.

External links

Infectious diseases · Bacterial diseases: BV4 non-proteobacterial G- (primarily A00–A79, 001–041, 080–109) Spirochaete TreponemaBorrelia recurrentis (Louse borne relapsing fever) · Borrelia hermsii/Borrelia duttoni/Borrelia parkeri (Tick borne relapsing fever)LeptospiraceaeLeptospira interrogans (Leptospirosis)SpirillaceaeSpirillum minus (Rat-bite fever/Sodoku)Chlamydiaceae Bacteroidetes Bacteroides fragilis · Bacteroides forsythus · Capnocytophaga canimorsus · Porphyromonas gingivalis · Prevotella intermediaFusobacteria Fusobacterium necrophorum (Lemierre's syndrome) · Fusobacterium nucleatum · Fusobacterium polymorphumStreptobacillus moniliformis (Rat-bite fever/Haverhill fever)Categories:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.