- Amsterdam

-

This article is about the Dutch capital. For other uses, see Amsterdam (disambiguation).

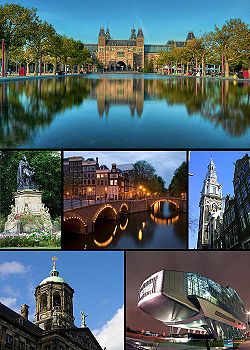

Amsterdam — Municipality/city — From left to right and top to bottom: Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, Statue in the Vondelpark, Keizersgracht, Zuiderkerk, Royal Palace (Amsterdam), ING House

Flag

Coat of armsNickname(s): Mokum, Venice of the North Motto: Heldhaftig, Vastberaden, Barmhartig

(Valiant, Steadfast, Compassionate)Location of Amsterdam Coordinates: 52°22′23″N 4°53′32″E / 52.37306°N 4.89222°ECoordinates: 52°22′23″N 4°53′32″E / 52.37306°N 4.89222°E Country Netherlands Province North Holland COROP Amsterdam Boroughs Boroughs Government – Mayor Eberhard van der Laan (Labour Party) – Aldermen Lodewijk Asscher

Eric van der Burg

Andrée van Es

Carolien Gehrels

Freek Ossel

Maarten van Poelgeest

Eric Wiebes– Secretary Henk de Jong Area[1][2] – Municipality/city 219 km2 (84.6 sq mi) – Land 166 km2 (64.1 sq mi) – Water 53 km2 (20.5 sq mi) – Metro 1,815 km2 (700.8 sq mi) Elevation[3] 2 m (7 ft) Population (31 December 2010)[4][5] – Municipality/city 780,152 – Density 3,506/km2 (9,080.5/sq mi) – Urban 1,209,419 – Metro 2,158,592 – Demonym Amsterdammer Time zone CET (UTC+01) – Summer (DST) CEST (UTC+02) (UTC) Postal codes 1011–1109 Area code(s) 020 Website www.amsterdam.nl Amsterdam (/ˈæmstərdæm/; Dutch [ˌɑmstərˈdɑm] (

listen)) is the largest city and the capital of the Netherlands. The current position of Amsterdam as capital city of the Kingdom of the Netherlands is governed by the constitution of August 24, 1815 and its successors.[6] Amsterdam has a population of 783,364 within city limits, an urban population of 1,209,419 and a metropolitan population of 2,158,592.[7] The city is in the province of North Holland in the west of the country. It comprises the northern part of the Randstad, one of the larger conurbations in Europe, with a population of approximately 7 million.[8]

listen)) is the largest city and the capital of the Netherlands. The current position of Amsterdam as capital city of the Kingdom of the Netherlands is governed by the constitution of August 24, 1815 and its successors.[6] Amsterdam has a population of 783,364 within city limits, an urban population of 1,209,419 and a metropolitan population of 2,158,592.[7] The city is in the province of North Holland in the west of the country. It comprises the northern part of the Randstad, one of the larger conurbations in Europe, with a population of approximately 7 million.[8]Its name is derived from Amstelredamme,[9] indicative of the city's origin: a dam in the river Amstel. Settled as a small fishing village in the late 12th century, Amsterdam became one of the most important ports in the world during the Dutch Golden Age, a result of its innovative developments in trade. During that time, the city was the leading center for finance and diamonds.[10] In the 19th and 20th centuries, the city expanded, and many new neighborhoods and suburbs were formed. The 17th-century canals of Amsterdam (in Dutch: 'Grachtengordel'), located in the heart of Amsterdam, were added to the UNESCO World Heritage List in July 2010.

The city is the financial and cultural capital of the Netherlands.[11] Many large Dutch institutions have their headquarters there, and 7 of the world's top 500 companies, including Philips and ING, are based in the city.[12] In 2010, Amsterdam was ranked 13th globally on quality of living[13] by Mercer, and previously ranked 3rd in innovation by 2thinknow in the Innovation Cities Index 2009.[14]

The Amsterdam Stock Exchange, the oldest stock exchange in the world, is located in the city center. Amsterdam's main attractions, including its historic canals, the Rijksmuseum, the Van Gogh Museum, Stedelijk Museum, Hermitage Amsterdam, Anne Frank House, Amsterdam Museum, its red-light district, and its many cannabis coffee shops draw more than 3.66 million international visitors annually.

Contents

History

Main article: History of AmsterdamThe earliest recorded use of the name "Amsterdam" is from a certificate dated October 27, 1275, when the inhabitants, who had built a bridge with a dam across the Amstel, were exempted from paying a bridge toll by Count Floris V.[15] The certificate describes the inhabitants as homines manentes apud Amestelledamme (people living near Amestelledamme).[16] By 1327, the name had developed into Aemsterdam.[15] Amsterdam's founding is relatively recent compared with much older Dutch cities such as Nijmegen, Rotterdam, and Utrecht. In October 2008, historical geographer Chris de Bont suggested that the land around Amsterdam was being reclaimed as early as the late 10th century. This does not necessarily mean that there was already a settlement then since reclamation of land may not have been for farming—it may have been for peat, used as fuel.[17]

A painting depicting Amsterdam as of 1544. The famous Grachtengordel had not yet been established.

Amsterdam was granted city rights in either 1300 or 1306.[18] From the 14th century on, Amsterdam flourished, largely because of trade with the Hanseatic League. In 1345, an alleged Eucharistic miracle in the Kalverstraat rendered the city an important place of pilgrimage until the adoption of the Protestant faith. The Stille Omgang—a silent procession in civil attire—is today a remnant of the rich pilgrimage history.[19]

In the 16th century, the Dutch rebelled against Philip II of Spain and his successors. The main reasons for the uprising were the imposition of new taxes, the tenth penny, and the religious persecution of Protestants by the Spanish Inquisition. The revolt escalated into the Eighty Years' War, which ultimately led to Dutch independence.[20] Strongly pushed by Dutch Revolt leader William the Silent, the Dutch Republic became known for its relative religious tolerance. Jews from the Iberian Peninsula, Huguenots from France, prosperous merchants and printers from Flanders, and economic and religious refugees from the Spanish-controlled parts of the Low Countries found safety in Amsterdam. The influx of Flemish printers and the city's intellectual tolerance made Amsterdam a center for the European free press.[21]

The 17th century is considered Amsterdam's Golden Age, during which it became the wealthiest city in the world.[22] Ships sailed from Amsterdam to the Baltic Sea, North America, and Africa, as well as present-day Indonesia, India, Sri Lanka, and Brazil, forming the basis of a worldwide trading network. Amsterdam's merchants had the largest share in both the Dutch East India Company and the Dutch West India Company. These companies acquired overseas possessions that later became Dutch colonies. Amsterdam was Europe's most important point for the shipment of goods and was the leading Financial Center of the world.[23] In 1602, the Amsterdam office of the Dutch East India Company became the world's first stock exchange by trading in its own shares.[24]

Amsterdam lost over 10% of its population to plague in 1623–1625, and again in 1635–1636, 1655, and 1664. Nevertheless, the population of Amsterdam rose in the 17th century (largely through immigration) from 50,000 to 200,000.[25]

Amsterdam's prosperity declined during the 18th and early 19th centuries. The wars of the Dutch Republic with England and France took their toll on Amsterdam. During the Napoleonic Wars, Amsterdam's significance reached its lowest point, with Holland being absorbed into the French Empire. However, the later establishment of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands in 1815 marked a turning point.

The end of the 19th century is sometimes called Amsterdam's second Golden Age.[26] New museums, a train station, and the Concertgebouw were built; in this same time, the Industrial Revolution reached the city. The Amsterdam-Rhine Canal was dug to give Amsterdam a direct connection to the Rhine, and the North Sea Canal was dug to give the port a shorter connection to the North Sea. Both projects dramatically improved commerce with the rest of Europe and the world. In 1906, Joseph Conrad gave a brief description of Amsterdam as seen from the seaside, in The Mirror of the Sea. Shortly before the First World War, the city began expanding, and new suburbs were built. Even though the Netherlands remained neutral in this war, Amsterdam suffered a food shortage, and heating fuel became scarce. The shortages sparked riots in which several people were killed. These riots are known as the Aardappeloproer (Potato rebellion). People started looting stores and warehouses in order to get supplies, mainly food.[27]

Germany invaded the Netherlands on May 10, 1940 and took control of the country. Some Amsterdam citizens sheltered Jews, thereby exposing themselves and their families to the high risk of being imprisoned or sent to concentration camps. More than 100,000 Dutch Jews were deported to Nazi concentration camps. Perhaps the most famous deportee was the young Jewish girl Anne Frank, who died in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp.[28] At the end of the Second World War, communication with the rest of the country broke down, and food and fuel became scarce. Many citizens traveled to the countryside to forage. Dogs, cats, raw sugar beets, and Tulip bulbs—cooked to a pulp—were consumed to stay alive.[29] Most of the trees in Amsterdam were cut down for fuel, and all the wood was taken from the apartments of deported Jews.

Many new suburbs, such as Osdorp, Slotervaart, Slotermeer, and Geuzenveld, were built in the years after the Second World War.[30] These suburbs contained many public parks and wide, open spaces, and the new buildings provided improved housing conditions with larger and brighter rooms, gardens, and balconies. Because of the war and other incidents of the 20th century, almost the entire city center had fallen into disrepair. As society was changing, politicians and other influential figures made plans to redesign large parts of it. There was an increasing demand for office buildings and new roads as the automobile became available to most common people.[31] A metro started operating in 1977 between the new suburb of Bijlmer and the center of Amsterdam. Further plans were to build a new highway above the metro to connect the Central Station and city center with other parts of the city.

The incorporated large-scale demolitions began in Amsterdam's formerly Jewish neighborhood. Smaller streets, such as the Jodenbreestraat, were widened and saw almost all of their houses demolished. During the destruction's peak, the Nieuwmarktrellen (Nieuwmarkt riots) broke out,[32] where people expressed their fury about the demolition caused by the restructuring of the city. As a result, the demolition was stopped, and the highway was never built, with only the metro being finished. Only a few streets remained widened. The new city hall was built on the almost completely demolished Waterlooplein. Meanwhile, large private organisations, such as Stadsherstel Amsterdam, were founded with the aim of restoring the entire city center. Although the success of this struggle is visible today, efforts for further restoration are still ongoing.[31] The entire city center has reattained its former splendor and, as a whole, is now a protected area. Many of its buildings have become monuments, and in July 2010 the Grachtengordel (Herengracht, Keizersgracht, and Prinsengracht) was added to the UNESCO World Heritage List.[33]

Geography

Satellite image of Amsterdam

Satellite image of Amsterdam

Amsterdam is part of the province of North-Holland and is located in the west of the Netherlands next to the provinces of Utrecht and Flevoland. The river Amstel terminates in the city center and connects to a large number of canals that eventually terminate in the IJ. Amsterdam is situated 2 metres above sea level.[3] The surrounding land is flat as it is formed of large polders. To the southwest of the city lies a man-made forest called het Amsterdamse Bos. Amsterdam is connected to the North Sea through the long North Sea Canal.

Amsterdam is intensely urbanized, as is the Amsterdam metropolitan area surrounding the city. Comprising 219.4 square kilometres of land, the city proper has 4,457 inhabitants per km2 and 2,275 houses per km2.[34] Parks and nature reserves make up 12% of Amsterdam's land area.[35]

Climate

Amsterdam has an oceanic climate (Köppen climate classification Cfb), strongly influenced by its proximity to the North Sea to the west, with prevailing westerly winds. Winters are mild. Amsterdam, as well as most of the North-Holland province, lies in USDA Hardiness zone 8, the northernmost such occurrence in continental Europe. Frosts mainly occur during spells of easterly or northeasterly winds from the inner European continent. Even then, because Amsterdam is surrounded on three sides by large bodies of water, as well as enjoying a significant heat-island effect, nights rarely fall below −5 °C (23 °F), while it could easily be −12 °C (10 °F) in Hilversum, 25 kilometres southeast. Summers are moderately warm but rarely hot. The average daily high in August is 21.8 °C (71.2 °F), and 30 °C (86 °F) or higher is only measured on average on 3 days, placing Amsterdam in AHS Heat Zone 2. Days with measurable precipitation are common, on average 186 days per year. Amsterdam's average annual precipitation is 833 millimetres (32.8 in). A large part of this precipitation falls as light rain or brief showers. Cloudy and damp days are common during the cooler months of October through March.

Climate data for Amsterdam (1981–2010 data) Month Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Year Average high °C (°F) 5

(41)6

(43)10

(50)14

(57)18

(64)21

(70)23

(73)23

(73)20

(68)16

(61)10

(50)6

(43)15 Daily mean °C (°F) 3.1

(37.6)3.3

(37.9)6.2

(43.2)9.2

(48.6)13.1

(55.6)15.6

(60.1)17.9

(64.2)17.5

(63.5)14.5

(58.1)10.7

(51.3)6.7

(44.1)3.7

(38.7)10.1 Average low °C (°F) 1

(34)0

(32)3

(37)4

(39)8

(46)11

(52)13

(55)13

(55)10

(50)7

(45)3

(37)1

(34)6 Precipitation mm (inches) 69.6

(2.74)56.2

(2.213)66.8

(2.63)42.3

(1.665)61.9

(2.437)65.6

(2.583)81.1

(3.193)72.9

(2.87)78.1

(3.075)82.8

(3.26)79.8

(3.142)75.7

(2.98)832.8

(32.787)Sunshine hours 62.3 86.4 121.6 173.6 207.2 194.0 206.0 187.7 138.4 112.4 62.6 48.8 1,601 Source: MeteoGroup[36] Cityscape and architecture

Amsterdam fans out south from the Amsterdam Centraal railway station. The Damrak is the main street and leads into the street Rokin. The oldest area of the town is known as de Wallen (the quays). It lies to the east of Damrak and contains the city's famous red light district. To the south of de Wallen is the old Jewish quarter of Waterlooplein. The 17th century canals of Amsterdam, known as the Grachtengordel, embraces the heart of the city where homes have interesting gables. Beyond the Grachtengordel are the former working class areas of Jordaan and de Pijp. The Museumplein with the city's major museums, the Vondelpark, a 19th century park named after the Dutch writer Joost van den Vondel, and the Plantage neighborhood, with the zoo, are also located outside the Grachtengordel.

Several parts of the city and the surrounding urban area are polders. This can be recognized by the suffix -meer which means lake, as in Aalsmeer, Bijlmermeer, Haarlemmermeer, and Watergraafsmeer.

Canals

Main article: Canals of AmsterdamThe Amsterdam canal system is the result of conscious city planning.[37] In the early 17th century, when immigration was at a peak, a comprehensive plan was developed that was based on four concentric half-circles of canals with their ends emerging at the IJ bay. Known as the Grachtengordel, three of the canals were mostly for residential development: the Herengracht (where "Heren" refers to Heren Regeerders van de stad Amsterdam (ruling lords of Amsterdam), and gracht means canal, so the name can be roughly translated as "Canal of the lords"), Keizersgracht (Emperor's Canal), and Prinsengracht (Prince's Canal).[38] The fourth and outermost canal is the Singelgracht, which is often not mentioned on maps, because it is a collective name for all canals in the outer ring. The Singelgracht should not be confused with the oldest and most inner canal Singel. The canals served for defense, water management and transport. The defenses took the form of a moat and earthen dikes, with gates at transit points, but otherwise no masonry superstructures.[39] The original plans have been lost, so historians, such as Ed Taverne, need to speculate on the original intentions: it is thought that the considerations of the layout were purely practical and defensive rather than ornamental.[40]

Construction started in 1613 and proceeded from west to east, across the breadth of the layout, like a gigantic windshield wiper as the historian Geert Mak calls it – and not from the center outwards, as a popular myth has it. The canal construction in the southern sector was completed by 1656. Subsequently, the construction of residential buildings proceeded slowly. The eastern part of the concentric canal plan, covering the area between the Amstel river and the IJ bay, has never been implemented. In the following centuries, the land was used for parks, senior citizens' homes, theaters, other public facilities, and waterways without much planning.[41]

Over the years, several canals have been filled in, becoming streets or squares, such as the Nieuwezijds Voorburgwal and the Spui.[42]

Expansion

Main article: Expansion of AmsterdamAfter the development of Amsterdam's canals in the 17th century, the city did not grow beyond its borders for two centuries. During the 19th century, Samuel Sarphati devised a plan based on the grandeur of Paris and London at that time. The plan envisaged the construction of new houses, public buildings and streets just outside the grachtengordel. The main aim of the plan, however, was to improve public health. Although the plan did not expand the city, it did produce some of the largest public buildings to date, like the Paleis voor Volksvlijt.[43][44][45]

Following Sarphati, Van Niftrik and Kalff designed an entire ring of 19th century neighborhoods surrounding the city’s center, with the city preserving the ownership of all land outside the 17th century limit, thus firmly controlling development.[46] Most of these neighborhoods became home to the working class.[47]

In response to overcrowding, two plans were designed at the beginning of the 20th century which were very different from anything Amsterdam had ever seen before: Plan Zuid, designed by the architect Berlage, and West. These plans involved the development of new neighborhoods consisting of housing blocks for all social classes.[48][49]

After the Second World War, large new neighborhoods were built in the western, southeastern, and northern parts of the city. These new neighborhoods were built to relieve the city's shortage of living space and give people affordable houses with modern conveniences. The neighborhoods consisted mainly of large housing blocks situated among green spaces, connected to wide roads, making the neighborhoods easily accessible by motor car. The western suburbs which were built in that period are collectively called the Westelijke Tuinsteden. The area to the southeast of the city built during the same period is known as the Bijlmer.[50][51]

Architecture

Built in the Renaissance style, designed by the Dutch architect Hendrick de Keyser, the Westertoren (1637) is the highest church tower (85m) in Amsterdam.

Built in the Renaissance style, designed by the Dutch architect Hendrick de Keyser, the Westertoren (1637) is the highest church tower (85m) in Amsterdam. The old city houses on Damrak

The old city houses on Damrak

Amsterdam has a rich architectural history. The oldest building in Amsterdam is the Oude Kerk (Old Church), at the heart of the Wallen, consecrated in 1306.[52] The oldest wooden building is het Houten Huys[53] at the Begijnhof. It was constructed around 1425 and is one of only two existing wooden buildings. It is also one of the few examples of Gothic architecture in Amsterdam.

In the 16th century, wooden buildings were razed and replaced with brick ones. During this period, many buildings were constructed in the architectural style of the Renaissance. Buildings of this period are very recognizable with their stepped gable façades, which is the common Dutch Renaissance style. Amsterdam quickly developed its own Renaissance architecture. These buildings were built according to the principles of the architect Hendrick de Keyser.[54] One of the most striking buildings designed by Hendrick de Keyer is the Westerkerk. In the 17th century baroque architecture became very popular, as it was elsewhere in Europe. This roughly coincided with Amsterdam’s Golden Age. The leading architects of this style in Amsterdam were Jacob van Campen, Philip Vingboons and Daniel Stalpaert.[55]

Early 20th century houses in the architecture of the Amsterdam School

Early 20th century houses in the architecture of the Amsterdam School

Philip Vingboons designed splendid merchants' houses throughout the city. A famous building in baroque style in Amsterdam is the Royal Palace on Dam Square. Throughout the 18th century, Amsterdam was heavily influenced by French culture. This is reflected in the architecture of that period. Around 1815, architects broke with the baroque style and started building in different neo-styles.[56] Most Gothic style buildings date from that era and are therefore said to be built in a neo-gothic style. At the end of the 19th century, the Jugendstil or Art Nouveau style became popular and many new buildings were constructed in this architectural style. Since Amsterdam expanded rapidly during this period, new buildings adjacent to the city center were also built in this style. The houses in the vicinity of the Museum Square in Amsterdam Oud-Zuid are an example of Jugendstil. The last style that was popular in Amsterdam before the modern era was Art Deco. Amsterdam had its own version of the style, which was called the Amsterdamse School. Whole districts were built this style, such as the Rivierenbuurt.[57] A notable feature of the façades of buildings designed in Amsterdamse School is that they are highly decorated and ornate, with oddly shaped windows and doors.

The old city center is the focal point of all the architectural styles before the end of the 19th century. Jugendstil and Art Deco are mostly found outside the city’s center in the neighborhoods built in the early 20th century, although there are also some striking examples of these styles in the city center. Most historic buildings in the city center and nearby are houses, such as the famous merchants' houses lining the canals.

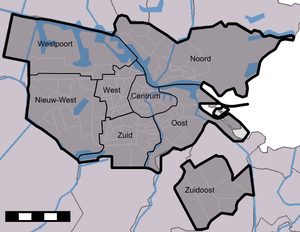

Government

The administration of the municipality of Amsterdam is divided into 15 boroughs or stadsdelen; the central one, Centrum, being circled by Westerpark, Bos en Lommer, De Baarsjes, Oud-West, Oud-Zuid, Oost/Watergraafsmeer, Zeeburg and Amsterdam-Noord, with the six outer boroughs (Westpoort, Geuzenveld-Slotermeer, Osdorp, Slotervaart, Zuideramstel, and Zuidoost) creating a further encirclement.[58] On 1 May 2010, the number of boroughs was reduced to eight (Centrum, Noord, Oost, Zuid, West, Nieuw-West, Zuidoost, and Westpoort).

Definitions

"Amsterdam" is usually understood to refer to the municipality of Amsterdam. Colloquially, some areas within the municipality, such as the village of Durgerdam, may not be considered part of Amsterdam. Statistics Netherlands uses three other definitions of Amsterdam: metropolitan agglomeration Amsterdam (Grootstedelijke Agglomeratie Amsterdam, not to be confused with Grootstedelijk Gebied Amsterdam, a synonym of Groot Amsterdam), Greater Amsterdam (Groot Amsterdam, a COROP region) and the urban region Amsterdam (Stadsgewest Amsterdam).[4] These definitions are not synonymous with the terms urban area and metropolitan area, which are commonly used in English speaking countries for the purpose of defining large conurbations. The Amsterdam Department for Research and Statistics uses a fourth conurbation, namely the City region Amsterdam. This region is similar to Greater Amsterdam but includes the municipalities Zaanstad and Wormerland. It excludes Graft-De Rijp.

The smallest of these areas is the municipality, with a population of 742,981 in 2006.[59] The metropolitan agglomeration had a population of 1,021,870 in 2006.[59] It includes the municipalities of Zaanstad, Wormerland, Oostzaan, Diemen and Amstelveen only, as well as the municipality of Amsterdam. Greater Amsterdam includes 15 municipalities,[60] and had a population of 1,211,503 in 2006.[59] Though much larger in area, the population of this area is only slightly larger, because the definition excludes the relatively populous municipality of Zaanstad. The largest area by population, the Amsterdam Metropolitan Area (Dutch: Metropoolregio Amsterdam), has a population of 2,22 million.[59] It includes for instance Zaanstad, Wormerveer, Muiden, Abcoude, Haarlem, Almere and Lelystad but excludes Graft De Rijp. Amsterdam is part of the conglomerate metropolitan area Randstad, with a total population of 6,659,300 inhabitants.[5]

City government

Main article: Government of AmsterdamAs with all Dutch municipalities, Amsterdam is governed by a mayor, aldermen, and the municipal council. However, unlike most other Dutch municipalities, Amsterdam is subdivided into eight "stadsdelen" (boroughs), a system that was implemented in the 1980s to improve local governance. The stadsdelen are responsible for many activities that had previously been run by the central city. The city had initially been divided into 15 stadsdelen. 14 of those had their own council, chosen by a popular election. The 15th, Westpoort, covers the harbour of Amsterdam, had very few residents, and was governed by the central municipal council. Local decisions are made at borough level, and only affairs pertaining to the whole city, such as major infrastructure projects, are handled by the central city council.

National government

Amsterdam is the capital of the Netherlands in a technical legal sense. The present version of the Dutch constitution mentions "Amsterdam" and "capital" only in one place, chapter 2, article 32: The king's confirmation by oath and his coronation take place in "the capital Amsterdam" ("de hoofdstad Amsterdam"). Previous versions of the constitution spoke of "the city of Amsterdam" ("de stad Amsterdam"), without mention of capital.[61] In any case, the seat of the government, parliament and supreme court of the Netherlands is (and always has been, with the exception of a brief period between 1808 and 1810) located at The Hague. Foreign embassies are also in The Hague. The capital of North Holland is Haarlem.

Symbols

Main articles: Coat of arms of Amsterdam and Flag of AmsterdamThe coat of arms of Amsterdam

The coat of arms of Amsterdam is composed of several historical elements. First and center are three St Andrew's crosses, aligned in a vertical band on the city's shield (although Amsterdam's patron saint was Saint Nicholas). These St Andrew's crosses can also be found on the cityshields of neighbors Amstelveen and Ouder-Amstel. This part of the coat of arms is the basis of the flag of Amsterdam, flown by the city government, but also as civil ensign for ships registered in Amsterdam. Second is the Imperial Crown of Austria. In 1489, out of gratitude for services and loans, Maximilian I awarded Amsterdam the right to adorn its coat of arms with the king's crown. Then, in 1508, this was replaced with Maximilian's imperial crown when he was crowned Holy Roman Emperor. In the early years of the 17th century, Maximilian's crown in Amsterdam's coat of arms was again replaced, this time with the crown of Emperor Rudolph II, a crown that became the Imperial Crown of Austria. The lions date from the late 16th century, when city and province became part of the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands. Last came the city's official motto: Heldhaftig, Vastberaden, Barmhartig ("Heroic, Determined, Merciful"), bestowed on the city in 1947 by Queen Wilhelmina, in recognition of the city's bravery during the Second World War.

Economy

The Zuidas district is the main business district of Amsterdam and is still largely under construction. Many Dutch multinationals have their headquarters here, like ABN Amro and Akzo Nobel.

The Zuidas district is the main business district of Amsterdam and is still largely under construction. Many Dutch multinationals have their headquarters here, like ABN Amro and Akzo Nobel.

Amsterdam is the financial and business capital of the Netherlands.[62] Amsterdam is currently one of the best European cities in which to locate an International Business. It is ranked fifth in this category and is only surpassed by London, Paris, Frankfurt and Barcelona.[63] Many large corporations and banks have their headquarters in Amsterdam, including Royal Bank of Scotland, Akzo Nobel, Heineken International, ING Group, Ahold, TomTom, Delta Lloyd Group and Philips. KPMG International's global headquarters is located in nearby Amstelveen, where many non-Dutch companies have settled as well, because surrounding communities allow full land ownership, contrary to Amsterdam's land-lease system.

Though many small offices are still located on the old canals, companies are increasingly relocating outside the city center. The Zuidas (English: South Axis) has become the new financial and legal hub.[64] The five largest law firms of the Netherlands, a number of Dutch subsidiaries of large consulting firms like Boston Consulting Group and Accenture, and the World Trade Center Amsterdam are also located in Zuidas.

There are three other smaller financial districts in Amsterdam. The first is the area surrounding Amsterdam Sloterdijk railway station, where several newspapers like De Telegraaf have their offices. Also, the municipal public transport company (Gemeentelijk Vervoersbedrijf) and the Dutch tax offices (Belastingdienst) are located there. The second Financial District is the area surrounding Amsterdam Arena. The third is the area surrounding Amsterdam Amstel railway station. The tallest building in Amsterdam, the Rembrandt Tower, is situated there, as is the headquarters of Philips.[65][66]

The Amsterdam Stock Exchange (AEX), nowadays part of Euronext, is the world's oldest stock exchange and is one of Europe's largest bourses. It is situated near Dam Square in the city's center.

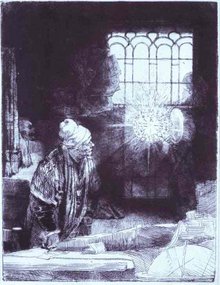

Tourism

Main article: List of tourist attractions in AmsterdamAmsterdam is one of the most popular tourist destinations in Europe, receiving more than 4.63 million international visitors annually.[67] The number of visitors has been growing steadily over the past decade. This can be attributed to an increasing number of European visitors. Two thirds of the hotels are located in the city's center. Hotels with 4 or 5 stars contribute 42% of the total beds available and 41% of the overnight stays in Amsterdam. The room occupation rate was 78% in 2006, up from 70% in 2005.[68] The majority of tourists (74%) originate from Europe. The largest group of non-European visitors come from the United States, accounting for 14% of the total.[68] Certain years have a theme in Amsterdam to attract extra tourists. For example, the year 2006 was designated "Rembrandt 400", to celebrate the 400th birthday of Rembrandt van Rijn. Some hotels offer special arrangements or activities during these years. The average number of guests per year staying at the four campsites around the city range from 12,000 to 65,000.[68]

Red light district

Main article: De WallenDe Wallen, also known as Walletjes or Rosse Buurt, is a designated area for legalised prostitution and is Amsterdam's largest and most well known red-light district. This neighborhood has become a famous tourist attraction. It consists of a network of roads and alleys containing several hundred small, one-room apartments rented by sex workers who offer their services from behind a window or glass door, typically illuminated with red lights.

Coffee shops

Contrary to wide spread rumours, Amsterdam's coffee shops will not be closing their doors to tourists any time soon. A controversial measure to introduce a "wietpas" (Dutch) or "weed-pass" membership system — pushed primarily by Christian political parties within the Dutch coalition government - is in the works; this pass would restrict coffee shop cannabis sales to residents of the Netherlands with a membership card only. The plan is widely unpopular and proponents face stiff opposition from figures such as Amsterdam's mayor, Eberhard van der Laan, and the Maastricht city council. Others have argued that the plan may indeed violate not only the constitution of the Netherlands but also that of the European Union. It is thus expected that the measure will fail before it is more closely considered.[69]

Retail

Shops in Amsterdam range from large department stores such as De Bijenkorf founded in 1870 and Maison de Bonneterie a Parisian style store founded in 1889, to small specialty shops. Amsterdam's high-end shops are found in the streets Pieter Cornelisz Hooftstraat and Cornelis Schuytstraat, which are located in the vicinity of the Vondelpark. One of Amsterdam's busiest high streets is the narrow, medieval Kalverstraat in the heart of the city. Another shopping area is the Negen Straatjes: nine narrow streets within the Grachtengordel, the concentric canal system of Amsterdam. The Negen Straatjes differ from other shopping districts with the presence of a large diversity of privately owned shops.

The city also features a large number of open-air markets such as the Albert Cuypmarkt, Westerstraat-markt, Ten Katemarkt, and Dappermarkt. Some of these markets are held on a daily basis, like the Albert Cuypmarkt and the Dappermarkt. Others, like the Westerstraat-markt, are held on a weekly basis.

Fashion

Fashion brands like G-star, Gsus, BlueBlood, Iris van Herpen, 10 feet and Warmenhoven & Venderbos, and fashion designers like Mart Visser, Viktor & Rolf, Sheila de Vries, Marlies Dekkers and Frans Molenaar are based in Amsterdam. Modelling agencies Elite Models, Touche models and Tony Jones have opened branches in Amsterdam. Supermodels Yfke Sturm, Doutzen Kroes and Kim Noorda started their careers in Amsterdam. Amsterdam has its garment center in the World Fashion Center. Buildings which formerly housed brothels in the red light district have been converted to ateliers for young fashion designers.

Demographics

Amsterdam has a population of 783,364 inhabitants. On January 1, 2011, the ethnic makeup of Amsterdam was 49.7% Dutch and 50.3% foreigners. In the 16th and 17th century non-Dutch immigrants to Amsterdam were mostly Huguenots, Flemings, Sephardi Jews and Westphalians. Huguenots came after the Edict of Fontainebleau in 1685, while the Flemish Protestants came during the Eighty Years' War. The Westphalians came to Amsterdam mostly for economic reasons – their influx continued through the 18th and 19th centuries. Before the Second World War, 10% of the city population was Jewish.

The first mass immigration in the 20th century were by people from Indonesia, who came to Amsterdam after the independence of the Dutch East Indies in the 1940s and 1950s. In the 1960s guest workers from Turkey, Morocco, Italy and Spain emigrated to Amsterdam. After the independence of Suriname in 1975, a large wave of Surinamese settled in Amsterdam, mostly in the Bijlmer area. Other immigrants, including refugees asylum seekers and illegal immigrants, came from Europe, America, Asia, and Africa. In the seventies and eighties, many 'old' Amsterdammers moved to 'new' cities like Almere and Purmerend, prompted by the third planological bill of the Dutch government. This bill promoted suburbanisation and arranged for new developments in so called "groeikernen", literally "cores of growth". Young professionals and artists moved into neighborhoods de Pijp and the Jordaan abandoned by these Amsterdammers. The non-Western immigrants settled mostly in the social housing projects in Amsterdam-West and the Bijlmer. Today, people of non-Western origin make up approximately one-third of the population of Amsterdam, and more than 50% of children.[70][71][72]

Immigration has led to demographic changes in many neighborhoods in Amsterdam, such as Osdorp pictured here.

Immigration has led to demographic changes in many neighborhoods in Amsterdam, such as Osdorp pictured here.

The Church of St. Nicholas (Sint Nicolaaskerk)

The Church of St. Nicholas (Sint Nicolaaskerk)

The largest religious group are Christians, who are divided between Roman Catholics and Protestants. The next largest religion is Islam, most of whose followers are Sunni.[73]

In 1578 the previously Roman Catholic city of Amsterdam joined the revolt against Spanish rule, late in comparison to other major northern Dutch cities. In line with Protestant procedure of that time, all churches were converted to Protestant worship. Calvinism became the dominant religion, and although Catholicism was not forbidden and priests allowed to serve, the Catholic hierarchy was prohibited. This led to the establishment of schuilkerken, covert churches, behind seemingly ordinary canal side house fronts. One example is the current debate center de Rode Hoed.

A large influx of foreigners of many religions came to 17th-century Amsterdam, in particular Sefardic Jews from Spain and Portugal, Huguenots from France, and Protestants from the Southern Netherlands. This led to the establishment of many non-Dutch-speaking religious churches. In 1603, the first notification was made of Jewish religious service. In 1639, the first synagogue was consecrated. The Jews came to call the town Jerusalem of the West, a reference to their sense of belonging there.

Historical populations Year Pop. ±% 1300[74] 1,000 — 1400[75] 3,000 +200.0% 1500[75] 15,000 +400.0% 1600[75] 54,000 +260.0% 1675[76] 206,000 +281.5% 1796[76] 200,600 −2.6% 1810[77] 180,000 −10.3% 1850[78] 224,000 +24.4% 1879[78] 317,000 +41.5% 1900[9] 523,577 +65.2% 1930[77] 757,000 +44.6% 2010[4] 780,152 +3.1% As they became established in the city, other Christian denominations used converted Catholic chapels to conduct their own services. The oldest English-language church congregation in the world outside the United Kingdom is found at the Begijnhof. Regular services there are still offered in English under the auspices of the Church of Scotland.[79] The Huguenots accounted for nearly 20% of Amsterdam's inhabitants in 1700. Being Calvinists, they soon integrated into the Dutch Reformed Church, though often retaining their own congregations. Some, commonly referred by the moniker 'Walloon', are recognizable today as they offer occasional services in French.

In the second half of the 17th century, Amsterdam experienced an influx of Ashkenazim, Jews from Central and Eastern Europe, which continued into the 19th century. Jews often fled the pogroms in those areas. The first Ashkenazi who arrived in Amsterdam were refugees from the Chmielnicki Uprising in Poland and the Thirty Years War. They not only founded their own synagogues, but had a strong influence on the 'Amsterdam dialect' adding a large Yiddish local vocabulary.

Despite an absence of an official Jewish ghetto, most Jews preferred to live in the eastern part of the old medieval heart of the city. The main street of this Jewish neighborhood was the Jodenbreestraat. The neighborhood comprised the Waterlooplein and the Nieuwmarkt.[80] Buildings in this neighborhood fell into disrepair after the Second World War, and a large section of the neighborhood was demolished during the construction of the subway. This led to riots, and as a result the original plans for large-scale reconstruction were abandoned and the neighborhood was rebuilt with smaller-scale residence buildings on the basis of its original layout.

Catholic Churches in Amsterdam have been constructed since the restoration of the episcopal hierarchy in 1853. One of the principal architects behind the city's Catholic churches, Cuypers, was also responsible for the Amsterdam Central Station and the Rijksmuseum, which led to a refusal of Protestant King William III to open 'that monastery'. In 1924, the Roman Catholic Church of the Netherlands hosted the International Eucharistic Congress in Amsterdam, and numerous Catholic prelates visited the city, where festivities were held in churches and stadiums. Catholic processions on the public streets, however, were still forbidden under law at the time. Only in the 20th century was Amsterdam's relation to Catholicism normalized, but despite its far larger population size, the Catholic clergy chose to place its episcopal see of the city in the nearby provincial town of Haarlem.[81]

In recent times, religious demographics in Amsterdam have been changed by large-scale immigration from former colonies. Immigrants from Suriname have introduced Evangelical Protestantism and Lutheranism, from the Hernhutter variety; Hinduism has been introduced mainly from Suriname; and several distinct branches of Islam have been brought from various parts of the world. Islam is now the largest non-Christian religion in Amsterdam. The large community of Ghanaian and Nigerian immigrants have established African churches, often in parking garages in the Bijlmer area, where many have settled. In addition, a broad array of other religious movements have established congregations, including Buddhism, Confucianism and Hinduism.

Although the saying "Leef en laat leven" or "Live and let live" summarizes the Dutch and especially the Amsterdam open and tolerant society, the increased influx of many races, religions, and cultures after the Second World War, has on a number of occasions strained social relations. With 176 different nationalities, Amsterdam is home to one of the widest varieties of nationalities of any city in the world.[82] The immigrant share of the population in the city proper now counts about 50%.[83]

Amsterdam has the common perception as an open and tolerant "anything-goes" society. However recently a shift in national politics has resulted in a stricter policies on dealing with minorities whereby a greater focus is placed on successful integration than on only celebrating and especially subsidising with taxpayer money their "unique" heritage. In recent years, politicians are actively discouraged against campaigning in minority languages. In the previous local elections politicians were criticized by current Amsterdam mayor Mr van der Laan (then minister of Integration) for distributing election leaflets in minority languages and in some cases leaflets were collected. Due to this anti-Multicultural stand in a multicultural city, van der Laan has been accused of hypocrisy by its own party's PvdA main candidate.[84]

Inhabitants by origin

In 2010, 34.9% of the total population and 52.6% of young people under 18 were of non-European origin.[85]

2010 Numbers % Autochthons 385,009 50.1 European Allochtoons 114,553 14.9 Non European Allochtoons 268,211 34.9 Surinam 68,881 9.0 Morocco 69,439 9.0 Turkey 40,370 5.3 Netherlands Antilles and Aruba 11,689 1.5 Others 77,832 10.1 Transport

Main article: Transport in AmsterdamIn the city center, driving a car is discouraged. Parking fees are expensive, and many streets are closed to cars or are one-way.[86] The local government sponsors carsharing and carpooling initiatives such as Autodelen and Meerijden.nu.[87]

Public transport in Amsterdam mainly consists of (night) bus and tram lines operated by Gemeentelijk Vervoerbedrijf. Regional buses, and some suburban buses, are operated by Connexxion and Arriva. Currently, there are 16 different tram lines, and four metro lines, with a fifth line, the North/South line, under construction. Three free ferries carry pedestrians and cyclists across the IJ to Amsterdam-Noord, and two fare-charging ferries run east and west along the harbour. There are also water taxis, a water bus, a boat sharing operation, electric rental boats (Boaty) and canal cruises, that transport people along Amsterdam's waterways.

The A10 ringroad surrounding the city connects Amsterdam with the Dutch national network of freeways. Interchanges on the A10 allow cars to enter the city by transferring to one of the 18 city roads, numbered S101 through to S118. These city roads are regional roads without grade separation, and sometimes without a central reservation. Most are accessible by cyclists. The S100 Centrumring is a smaller ringroad circumnavigating the city's center.

A tram crossing a bridge over the river Amstel

A tram crossing a bridge over the river Amstel

Amsterdam was intended in 1932 to be the hub, a kind of Kilometre Zero, of the highway system of the Netherlands,[88] with freeways numbered one through eight planned to originate from the city.[88] The outbreak of the Second World War and shifting priorities led to the current situation, where only roads A1, A2, and A4 originate from Amsterdam according to the original plan. The A3 road to Rotterdam was cancelled in 1970 in order to conserve the Groene Hart. Road A8, leading north to Zaandam and the A10 Ringroad were opened between 1968 and 1974.[89] Besides the A1, A2, A4 and A8, several freeways, such as the A7 and A6, carry traffic mainly bound for Amsterdam.

Amsterdam is served by ten stations of the Nederlandse Spoorwegen (Dutch Railways).[90] Five are intercity stops: Sloterdijk, Zuid, Amstel, Bijlmer ArenA and Amsterdam Centraal. The stations for local services are: Lelylaan, RAI, Holendrecht, Muiderpoort and Science Park. Amsterdam Centraal is also an international train station. From the station there are regular services to destinations such as Austria, Belarus, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Germany, Hungary, Poland, Russia and Switzerland. Among these trains are international trains of the Nederlandse Spoorwegen and the Thalys(Amsterdam-Brussels-Paris-Cologne), CityNightLine, and InterCityExpress.[91]

A bicyclist crossing a bridge over the Leidsegracht.

A bicyclist crossing a bridge over the Leidsegracht.

Eurolines has coaches from Amsterdam Amstel railway station to destinations all over Europe.

Amsterdam Airport Schiphol is less than 20 minutes by train from Amsterdam Central Station. It is the biggest airport in the Netherlands, the fifth largest in Europe, and the twelfth largest in the world in terms of passengers. It handles about 46 million passengers per year and is the home base of four airlines, KLM, transavia.com, Martinair and Arkefly. Schiphol was, in 2006, the third busiest airport in the world measured by international passengers.[92][93]

Cycling

Main article: Cycling in AmsterdamAmsterdam is one of the most bicycle-friendly large cities in the world and is a center of bicycle culture with good facilities for cyclists such as bike paths and bike racks, and several guarded bike storage garages (Fietsenstalling) which can be used for a nominal fee. In 2006, there were about 465,000 bicycles in Amsterdam.[94] Theft is widespread – in 2005, about 54,000 bicycles were stolen in Amsterdam.[95] Bicycles are used by all socio-economic groups because of their convenience, Amsterdam's small size, the 400 km of bike paths,[96] the flat terrain, and the arguable inconvenience of driving an automobile.

Education

Amsterdam has two universities: the University of Amsterdam (Universiteit van Amsterdam), and the VU University Amsterdam (Vrije Universiteit or "VU" – often referred to, in English, as "The Free"). Other institutions for higher education include an art school – Gerrit Rietveld Academie, the Hogeschool van Amsterdam, and the Amsterdamse Hogeschool voor de Kunsten. Amsterdam's International Institute of Social History is one of the world's largest documentary and research institutions concerning social history, and especially the history of the labour movement. Amsterdam's Hortus Botanicus, founded in the early 17th century, is one of the oldest botanical gardens in the world,[97] with many old and rare specimens, among them the coffee plant that served as the parent for the entire coffee culture in Central and South America.[98]

Some of Amsterdam's primary schools base their teachings on particular pedagogic theories like the various Montessori schools. The biggest Montessori High School in Amsterdam is the Montessori Lyceum Amsterdam. Many schools, however, are based on religion. This used to be primarily Roman Catholicism and various Protestant denominations, but with the influx of Muslim immigrants there has been a rise in the number of Islamic schools. Jewish schools can be found in the southern suburbs of Amsterdam.

Amsterdam is noted for having five independent grammar schools (Dutch: gymnasia), the Vossius Gymnasium, Barlaeus Gymnasium, St. Ignatius Gymnasium, Het 4e Gymnasium and the Cygnus Gymnasium where a classical curriculum including Latin and classical Greek is taught. Though believed until recently by many to be an anachronistic and elitist concept that would soon die out, the gymnasia have recently experienced a revival, leading to the formation of a fourth and fifth grammar school in which the three aforementioned schools participate. Most secondary schools in Amsterdam offer a variety of different levels of education in the same school. The city also has various colleges ranging from art and design to politics and economics which are mostly also available for students coming from other countries.

Housing

The housing market is heavily regulated. In Amsterdam, 55% of existing housing and 80% of new housing is owned by Housing Associations, which are Government sponsored entities.

Squat properties are common throughout Amsterdam, due to property law strongly favouring tenants. A number of these squats have become well known, such as OT301, Vrankrijk (closed down by city government), and the Binnenpret, and several are now businesses, such as health clubs and licensed restaurants.

Culture and entertainment

During the later part of the 16th century Amsterdam's Rederijkerskamer (Chamber of Rhetoric) organized contests between different Chambers in the reading of poetry and drama. In 1638, Amsterdam opened its first theater. Ballet performances were given in this theater as early as 1642. In the 18th century, French theater became popular. While Amsterdam was under the influence of German music in the 19th century there were few national opera productions; the Hollandse Opera of Amsterdam was built in 1888 for the specific purpose of promoting Dutch opera.[99] In the 19th century, popular culture was centered around the Nes area in Amsterdam (mainly vaudeville and music-hall).[citation needed] The metronome, one of the most important advances in European classical music, was invented here in 1812 by Dietrich Nikolaus Winkel. At the end of this century, the Rijksmuseum and Stedelijk Museum were built.[citation needed] In 1888, the Concertgebouworkest was established. With the 20th century came cinema, radio and television.[citation needed] Though most studios are located in Hilversum and Aalsmeer, Amsterdam's influence on programming is very strong. Many people who work in the television industry live in Amsterdam. Also, the headquarters of SBS 6 is located in Amsterdam.[100]

Museums

The most important museums of Amsterdam are located on the Museumplein (Museum Square), located at the southwestern side of the Rijksmuseum. It was created in the last quarter of the 19th century on the grounds of the former World's fair. The northeastern part of the square is bordered by the very large Rijksmuseum. In front of the Rijksmuseum on the square itself is a long, rectangular pond. This is transformed into an ice rink in winter.[101] The northwestern part of the square is bordered by the Van Gogh Museum, Stedelijk Museum, House of Bols Cocktail & Genever Experience and Coster Diamonds. The southwestern border of the Museum Square is the Van Baerlestraat, which is a major thoroughfare in this part of Amsterdam. The Concertgebouw is situated across this street from the square. To the southeast of the square are situated a number of large houses, one of which contains the American consulate. A parking garage can be found underneath the square, as well as a supermarket. Het Museumplein is covered almost entirely with a lawn, except for the northeastern part of the square which is covered with gravel. The current appearance of the square was realized in 1999, when the square was remodeled. The square itself is the most prominent site in Amsterdam for festivals and outdoor concerts, especially in the summer. Plans were made in 2008 to remodel the square again, because many inhabitants of Amsterdam are not happy with its current appearance.[102]

The Rijksmuseum possesses the largest and most important collection of classical Dutch art.[103] It opened in 1885. Its collection consists of nearly one million objects.[104] The artist most associated with Amsterdam is Rembrandt, whose work, and the work of his pupils, is displayed in the Rijksmuseum. Rembrandt's masterpiece De Nachtwacht (The Night Watch) is one of top pieces of art of the museum. It also houses paintings from artists like Van der Helst, Vermeer, Frans Hals, Ferdinand Bol, Albert Cuyp, Jacob van Ruisdael and Paulus Potter. Aside from paintings, the collection consists of a large variety of decorative art. This ranges from Delftware to giant dollhouses from the 17th century. The architect of the gothic revival building was P.J.H. Cuypers. At present, the museum is being expanded, renovated, and a new main entrance for the museum created. Only one wing of the Rijksmuseum is currently open to the public, with a selection of master pieces on display. The full museum will re-open in 2012 or 2013.[105]

Van Gogh lived in Amsterdam for a short while and there is a museum dedicated to his work. The museum is housed in one of the few modern buildings in this area of Amsterdam. The building was designed by Gerrit Rietveld. This building is where the permanent collection is displayed. A new building was added to the museum in 1999. This building, known as the performance wing, was designed by Japanese architect Kisho Kurokawa. Its purpose is to house temporary exhibitions of the museum. Some of Van Gogh's most famous paintings, like the Aardappeleters (The Potato Eaters) and Zonnebloemen (Sunflowers), are present in the collection. The Van Gogh museum is the most visited museum in Amsterdam.[106][107][108]

Next to the Van Gogh museum stands the Stedelijk Museum. This is Amsterdam's largest museum concerning modern art. The museum opened its doors at around the same time the Museum Square was created. The permanent collection consists of works of art from artists like Piet Mondriaan, Karel Appel, and Kazimir Malevich. This museum is also currently being renovated and expanded. The main entrance will be relocated from the Paulus Potterstraat to the Museum Square itself. It will be open again to public in the end of 2011.

Amsterdam contains many other museums throughout the city. They range from small museums such as the Verzetsmuseum (Resistance Museum), the Anne Frank Huis (Anne Frank House), and the Rembrandthuis (Rembrandt House), to the very large, like the Tropenmuseum (Museum of the Tropics), Amsterdam Museum (formerly known as "Amsterdams Historisch Museum", Amsterdam Historical Museum), Hermitage Amsterdam (a dependency of the Hermitage Museum of Saint Petersburg) and the Joods Historisch Museum (Jewish Historical Museum). The modern-styled NEMO (museum) is dedicated to child-friendly science exhibitions.

Performing arts

Pop, rock, and jazz

The Heineken Music Hall is a concert hall located near the Amsterdam ArenA. Its main purpose is to serve as a podium for pop concerts for big audiences. Many famous international artists have performed there. Two other notable venues, Paradiso and the Melkweg are located near the Leidseplein. Both focus on broad programming, ranging from indie rock to hip hop, R&B, and other popular genres. Other more subculturally focused music venues are OCCII, OT301, De Nieuwe Anita, Winston Kingdom and Zaal 100. Jazz has a strong following in Amsterdam, with the Bimhuis being the premier venue.

Electronic Dance Music

The Heineken Music Hall is also host to many Electronic Dance Music festivals, alongside many other venues. Amsterdam is home to Scantraxx, which is one of the largest record labels that produces Hardstyle music, which is very popular in the Netherlands. Armin van Buuren and Tiesto, some of the worlds leading Trance DJ's hail from The Netherlands and perform frequently in Amsterdam. Each year in October, the city hosts the Amsterdam Dance Event (ADE) which is one of the leading electronic music conferences and one of the biggest club festivals for electronic music in the world. Another popular dance festival is 5daysoff, which takes place in the venues Paradiso and Melkweg. In summer time there are several big outdoor dance parties in or nearby Amsterdam, such as Awakenings, Dance Valley, Mystery Land, Loveland, A Day at the Park, Welcome to the Future, and Valtifest.

Classical music

The Grote Zaal of the Concertgebouw

The Grote Zaal of the Concertgebouw

Amsterdam has a world-class symphony orchestra, the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra. Their home is the Concertgebouw, which is across the Van Baerlestraat from the Museum Square. It is considered by critics to be a concert hall with some of the best acoustics in the world. The building contains three halls, Grote Zaal, Kleine Zaal, and Spiegelzaal. Eight hundred concerts per year are performed there for approximately 850,000 patrons.[109]

The opera house of Amsterdam is situated adjacent to the city hall. Therefore, the two buildings combined are often called the Stopera. This word is derived from the Dutch words stadhuis (city hall) and opera. This huge modern complex, opened in 1986, lies in the former Jewish neighborhood at Waterlooplein next to the river Amstel. The Stopera is the homebase of De Nederlandse Opera, Het Nationale Ballet and the Holland Symfonia.

Muziekgebouw aan 't IJ is a concert hall, which is situated in the IJ near the central station. Its concerts perform mostly modern classical music. Located adjacent to it, is the Bimhuis, a concert hall for improvised and Jazz music.

Theater

The main theater building of Amsterdam is the Stadsschouwburg Amsterdam at the Leidseplein. It is the home base of the Toneelgroep Amsterdam. The current building dates from 1894. Most plays are performed in the Grote Zaal (Great Hall). The normal program of events encompasses all sorts of theatrical forms. The Stadsschouwburg is currently being renovated and expanded. The third theater space, to be operated jointly with next door Melkweg, will open in late 2009 or early 2010. Other theaters are: Royal Theater Carré, Bellevue theaters, the Stopera de kleine komedie and the re-opened DeLaMar.

Comedy and cabaret

The Netherlands has a tradition of cabaret or kleinkunst, which combines music, storytelling, commentary, theater and comedy. Cabaret dates back to the 1930s and artists like Wim Kan, Wim Sonneveld and Toon Hermans were pioneers of this form of art in the Netherlands. In Amsterdam is the Kleinkunstacademie (English: Cabaret Academy).

Contemporary popular artists are Youp van 't Hek, Freek de Jonge, Herman Finkers, Hans Teeuwen, Theo Maassen, Herman van Veen, Najib Amhali, Raoul Heertje, Jörgen Raymann, De Vliegende Panters and Comedytrain. The English spoken comedy scene was established with the founding of Boom Chicago in 1993. They have their own theater at Leidseplein.

Nightlife

Amsterdam is famous for its vibrant and diverse nightlife. The two main nightlife areas are the Leidseplein and the Rembrandtplein.

Amsterdam has many cafés (bars). They range from large and modern to small and cozy. The typical Bruine Kroeg (brown café) breathe a more old fashioned atmosphere with dimmed lights, candles, and somewhat older clientele. Most cafés have terraces in summertime. A common sight on the Leidseplein during summer is a square full of terraces packed with people drinking beer or wine.

Many restaurants can be found in Amsterdam as well. Since Amsterdam is a multicultural city, a lot of different ethnic restaurants can be found. Restaurants range from being rather luxurious and expensive to being ordinary and affordable.

Amsterdam also possesses many discothèques. Most of these 'clubs' are situated near the Leidseplein and Rembrandtplein. The Paradiso, Melkweg and Sugar Factory are cultural centers, which turn into discothèques on some nights. Examples of discothèques near the Rembrandtplein are the Escape and Club Home. Also noteworthy are Panama, Hotel Arena (East), The Sand and The Powerzone.

Bimhuis located near the Central Station, with its rich programming hosting the best in the field is considered one of the best jazz clubs in the world.

The Reguliersdwarsstraat is the main street for the LGBT community and nightlife.

Movie theaters

Hollywood films are primarily featured at cinemas owned by Pathe. Tuschinski is a heritage art deco building with a beautiful lobby and six screens. Theater One is an architectural treasure with comfortable seats, two balconies and recently restored ceilings. Pathe De Munt is modern and is located at the Muntplein. Pathe Arena is located a metro ride from the center and includes an IMAX auditorium. Pathe City is scheduled to reopen in 2010. Art films can be found at Tuschinski, and the independent The Movies, Cinecenter, Kriterion, Ketelhuis, Uitkijk, and the Filmmuseum.

Festivals

Koninginnedag 2009 in Amsterdam

Koninginnedag 2009 in Amsterdam

In 2008, there were 140 festivals and events in Amsterdam.[110] Famous festivals and events in Amsterdam include: Koninginnedag (Queen's Day); the Holland Festival for the performing arts; the yearly Prinsengrachtconcert (classical concerto on the Prinsen canal) in August; the 'Stille Omgang' (a silent Roman Catholic evening procession held every March); Amsterdam Gay Pride; The Cannabis Cup; and the Uitmarkt. On Koninginnedag—held each year on April 30—hundreds of thousands of people travel to Amsterdam to celebrate with the city's residents. The entire city becomes overcrowded with people buying products from the freemarket, or visiting one of the many music concerts.

The yearly Holland Festival attracts international artists and visitors from all over Europe. Amsterdam Gay Pride is a yearly local LGBT parade of boats in Amsterdam's canals, held on the first Saturday in August. The Gay Pride event is a frequent source of both criticism and praise.[111] The annual Uitmarkt is a three-day cultural event at the start of the cultural season in late August. It offers previews of many different artists, such as musicians and poets, who perform on podia.[112]

Sports

AFC Ajax's Amsterdam Arena

AFC Ajax's Amsterdam Arena

Amsterdam is home of the Eredivisie football club Ajax Amsterdam. The stadium Amsterdam ArenA is the home of Ajax. It is located in the south-east of the city next to the new Amsterdam Bijlmer ArenA railway station. Before it moved to its current location in 1996, Ajax played their regular matches in De Meer Stadion.[113] In 1928, Amsterdam hosted the Summer Olympics. The Olympic Stadium built for the occasion has been completely restored and is now used for cultural and sporting events, such as the Amsterdam Marathon.[114] The city itself played host to the road cycling events for those games.[115] Eight years earlier, Amsterdam assisted in hosting some of the sailing events for the Summer Olympics held in neighboring Antwerp, Belgium by hosting events at Buiten Y.

The ice hockey team Amstel Tijgers play in the Jaap Eden ice rink. The team competes in the Dutch ice hockey premier league. Speed skating championships have been held on the 400-metre (1,310 ft) lane of this ice rink.

Amsterdam holds two American Football franchises, the Amsterdam Crusaders, playing at Amsterdam Sloten, and the Amsterdam Panthers. The Amsterdam Pirates baseball team competes in the Dutch Major League. There are three field hockey teams, Amsterdam, Pinoké and Hurley, who play their matches around the Wagener Stadium in the nearby city of Amstelveen. The basketball team MyGuide Amsterdam competes in the Dutch premier division and play their games in the Sporthallen Zuid, near the Olympic Stadium.[116]

Since 1999 the city of Amsterdam honours the best sportsmen and women at the Amsterdam Sports Awards. Boxer Raymond Joval and field hockey midfielder Carole Thate were the first to receive the awards in 1999.

Kick boxing, Muay Thai and other martial arts are very popular in the country and especially in the city of Amsterdam.

International relations

See also: List of twin towns and sister cities in the NetherlandsTwin towns – Sister cities

Amsterdam is twinned with the following cities:[117]

City Municipality / District / Canton / Province / State / Region Country Since  Algiers

AlgiersAlgiers Province  Algeria

AlgeriaAthens

Attica

Attica Greece

GreeceBeijing[118] Beijing Municipality  China

China Brasilia

Brasilia Brazilian Federal District

Brazilian Federal District Brazil

Brazil Istanbul[119][120]

Istanbul[119][120]Marmara  Turkey

Turkey Kiev

KievKiev City Municipality  Ukraine

UkraineManchester Greater Manchester  United Kingdom

United Kingdom Managua

Managua Managua Municipality

Managua Municipality Nicaragua

Nicaragua1984  Montreal

Montreal Quebec

Quebec Canada

Canada Moscow

Moscow Federal City of Moscow

Federal City of Moscow Russia

RussiaNicosia Nicosia District  Cyprus

Cyprus Recife

Recife Pernambuco

Pernambuco Brazil

Brazil2009  Riga

RigaRiga Municipality  Latvia

Latvia Sarajevo

Sarajevo Sarajevo Canton

Sarajevo Canton Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia and HerzegovinaWillemstad Willemstad District  Curaçao

Curaçao2009 See also

References

- ^ "Kerncijfers voor Amsterdam en de stadsdelen". www.os.amsterdam.nl. Research and Statistics Service, City of Amsterdam. 1 January 2006. http://www.os.amsterdam.nl/tabel/4670/. Retrieved 4 April 2007.

- ^ "Area, population density, dwelling density and average dwelling occupation". www.os.amsterdam.nl. Research and Statistics Service, City of Amsterdam. 1 January 2006. http://www.os.amsterdam.nl/tabel/10216/. Retrieved 13 August 2008.

- ^ a b "Actueel Hoogtestand Nederland" (in Dutch). http://www.ahn.nl/. Retrieved May 18, 2008.

- ^ a b c [1][dead link] |title=Gemiddelde bevolking per regio naar leeftijd en geslacht |publisher=Statistics Netherlands |language=Dutch |accessdate=July 9, 2007}}

- ^ a b "Population" (in Dutch). Themes. City of Amsterdam. October 2008. http://www.os.amsterdam.nl/tabel/2008_mutatiestatistiek_stand.xls. Retrieved March 8, 2009.

- ^ Dutch Wikisource. "Grondwet voor het Koningrijk der Nederlanden (1815) (Dutch)". http://nl.wikisource.org/wiki/Grondwet_voor_het_Koningrijk_der_Nederlanden_(1815). Retrieved May 2, 2008.

- ^ "Facts and Figures". I amsterdam. http://www.iamsterdam.com/en/visiting/touristinformation/aboutamsterdam/factsandfigures. Retrieved June 1, 2011.

- ^ "Randstad2040; Facts & Figures (p.26)(in Dutch)" (PDF). VROM.

- ^ a b Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, Vol 1, p896-898.

- ^ Cambridge.org, Capitals of Capital -A History of International Financial Centers – 1780–2005, Youssef Cassis, ISBN 978-0521845359

- ^ After Athens in 1888 and Florence in 1986, Amsterdam was in 1986 chosen as the European Capital of Culture, confirming its eminent position in Europe and the Netherlands. See EC.europa.eu for an overview of the European cities and capitals of culture over the years.

- ^ Forbes.com, Forbes Global 2000 Largest Companies – Dutch rankings.

- ^ "Best cities in the world (Mercer)". City Mayors. May 26, 2010. http://www.citymayors.com/features/quality_survey.html. Retrieved October 10, 2010.

- ^ "2thinknow Innovation Cities Global 256 Index – worldwide innovation city rankings". Innovation-cities.com. July 30, 2009. http://www.innovation-cities.com/2thinknow-innovation-cities-global-256-index/. Retrieved October 10, 2010.

- ^ a b Berns, Jan; Daan, Jo (1993) (in Dutch). Hij zeit wat: de Amsterdamse volkstaal. The Hague: BZZTôH. p. 91. ISBN 90-6291-756-9.

- ^ "The toll privilege of 1275 in the Amsterdam City Archives". Stadsarchief.amsterdam.nl. http://stadsarchief.amsterdam.nl/english/amsterdam_treasures/trade/toll_privilege/index.en.html. Retrieved October 10, 2010.

- ^ "Amsterdam 200 jaar ouder dan aangenomen" (in Dutch). Nu.nl. October 22, 2008. http://www.nu.nl/news/1801750/80/rss/%27Amsterdam_200_jaar_ouder_dan_aangenomen%27.html. Retrieved October 22, 2008.

- ^ "De geschiedenis van Amsterdam" (in Dutch). Municipality of Amsterdam. http://amsterdam.nl/stad_in_beeld/geschiedenis/de_geschiedenis_van#Stadsrechten. Retrieved May 21, 2008.

- ^ "Mirakel van Amsterdam" (in Dutch). http://www.trouw.nl/laatstenieuws/laatstenieuws/article936256.ece/Katholieken_verzameld_voor_Mirakel_van_Amsterdam. Retrieved May 21, 2008.

- ^ "Eighty Years' War" (in Dutch). Leiden University. Archived from the original on May 12, 2008. http://web.archive.org/web/20080512110316/http://dutchrevolt.leidenuniv.nl/nederlands/default.htm. Retrieved May 21, 2008.

- ^ Case in point: After his trial and sentencing in Rome in 1633, Galileo chose Lodewijk Elzevir in Amsterdam to publish one of his finest works, Two New Sciences. See Wade Rowland (2003), Galileo's Mistake, A new look at the epic confrontation between Galileo and the Church, New York: Arcade Publishing, ISBN 1559706848, p. 260.

- ^ E. Haverkamp-Bergmann, Rembrandt; The Night Watch (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1982), p. 57

- ^ Amsterdam in the 17th Century, The University of North Carolina at Pembroke

- ^ Geography, climate, population, economy, society. J.P.Sommerville.

- ^ "Amsterdam through the ages -A medieval village becomes a global city". http://www.amsterdamcitywalks.com/english/agenda.html. Retrieved May 21, 2008.

- ^ "Aardappeloproer – Legermuseum" (in Dutch) (PDF). http://www.collectie.legermuseum.nl/sites/strategion/contents/i004516/arma39%20het%20aardappeloproer%20in%201917.pdf. Retrieved May 21, 2008.

- ^ "Deportation to camps". Hollandsche Schouwburg. http://www.hollandscheschouwburg.nl/site_en/deportatie/kader.html. Retrieved May 21, 2008.

- ^ "Kou en strijd in een barre winter" (in Dutch). NOS. http://www.nos.nl/nosjournaal/dossiers/60jaarbevrijding/60jaar_hongerwinter.html. Retrieved May 21, 2008.

- ^ "Stadsdeel Slotervaart – Geschiedenis" (in Dutch). Municipality Amsterdam. http://www.slotervaart.amsterdam.nl/stadsdeel_in_beeld/geschiedenis. Retrieved May 22, 2008.

- ^ a b "Stadsherstel Missie/Historie" (in Dutch). http://www.stadsherstelamsterdam.nl/. Retrieved May 22, 2008.

- ^ "Typisch Metrostad" (in Dutch). Municipality Amsterdam. http://amsterdam.nl/?ActItmIdt=101459. Retrieved May 22, 2008.

- ^ "Unesco World Heritage Site" (in Dutch). http://www.bma.amsterdam.nl/indexen/nieuws_bma?ActItmIdt=122633. Retrieved May 21, 2008.[dead link]

- ^ "Kerncijfers Amsterdam 2007" (in Dutch) (PDF). http://www.os.amsterdam.nl/pdf/2007_jaarboek_hoofdstuk_01.pdf. Retrieved May 18, 2008.

- ^ "Openbare ruimte en groen: Inleiding" (in Dutch). http://www.os.amsterdam.nl/feitenencijfers/24112/. Retrieved May 18, 2008.

- ^ "Nieuwe normaal 1981–2010". Meteo Consult. http://www.weer.nl. Retrieved January 24, 2011.

- ^ "Amsterdamse Grachten" (in Dutch). Municipality Amsterdam. Archived from the original on March 20, 2008. http://web.archive.org/web/20080320060143/http://amsterdam.nl/stad_in_beeld/werkstukken/grachten. Retrieved May 21, 2008.

- ^ "Vriendenwandelingroute2011.pdf". stadsherstel. http://www.stadsherstel.nl/content/ned/actualiteiten/Vriendenwandeling/documents/Vriendenwandelingroute2011.pdf. Retrieved July 21, 2011.

- ^ Taverne, E. R. M. (1978). In ‘t land van belofte, in de nieuwe stadt: ideaal en werkelijkheid van de stadsuitleg in de Republiek, 1580–1680 (In the land of promise, in the new city: ideal and reality of the city lay-out in the [Dutch] Republic, 1580–1680). Maarssen: Schwartz. ISBN 90-6179-024-7.

- ^ Amsterdam human capital – Google Books. Google. 2003. ISBN 9789053565957. http://books.google.com/?id=5UaM50-E-wwC&pg=PA33&dq=canals+of+Amsterdam&cd=5#v=onepage&q=canals%20of%20Amsterdam. Retrieved 11 January 2010.

- ^ Mak, G. (1995). Een kleine geschiedenis van Amsterdam. Amsterdam/Antwerp: Uitgeverij Atlas. ISBN 90-450-1232-4.

- ^ "Dempingen en Aanplempingen" (in Dutch). Walther Schoonenberg. http://www.onderdekeizerskroon.nl/wschoonenberg/dempingen.html. Retrieved May 21, 2008.

- ^ "Samuel Sarphati" (in Dutch). Joods Historisch Museum Amsterdam. http://www.jhm.nl/personen.aspx?naam=Sarphati%2C%20Samuel. Retrieved June 5, 2008.

- ^ "Uitbreidingsplan Sarphati" (in Dutch). Zorggroep Amsterdam. http://www.zorggroep-amsterdam.nl/pagina.php?id=124. Retrieved June 5, 2008.

- ^ "Samuel Sarphati" (in Dutch). JLG Real Estate. http://www.jlgrealestate.com/Samuel_Sarphati/Sarphatipark/. Retrieved June 5, 2008.

- ^ "Van Niftrik's plan at the Amsterdam City Archives". Stadsarchief.amsterdam.nl. http://stadsarchief.amsterdam.nl/english/amsterdam_treasures/maps/plan_van_niftrik/index.en.html. Retrieved October 10, 2010.

- ^ "Amsterdam Oud-Zuid" (in Dutch). BMZ. Archived from the original on January 13, 2008. http://web.archive.org/web/20080113182449/http://www.bmz.amsterdam.nl/adam/nl/oudzuid/index.html. Retrieved June 5, 2008.

- ^ "Berlage's Expansion Plan". Stadsarchief Amsterdam. http://stadsarchief.amsterdam.nl/english/amsterdam_treasures/planning/uitbreidingsplan_berlage/index.en.html. Retrieved June 5, 2008.

- ^ "Plan-Berlage" (in Dutch). Bureau Monumentenzorg Amsterdam. Archived from the original on May 14, 2006. http://web.archive.org/web/20060514181847/http://www.bmz.amsterdam.nl/adam/nl/intro/topo7.html. Retrieved June 5, 2008.

- ^ "Westelijke Tuinsteden" (in Dutch). Ymere. http://www.ymere.nl/ymere/template.asp?mnid=1&subid=35&cntid=119. Retrieved June 5, 2008.

- ^ "Ontwerp Westelijke Tuinsteden" (in Dutch). Archex.info. http://www.archex.info/nederlands/nederland/amsterdam_westelijke_tuinsteden.html. Retrieved June 5, 2008.

- ^ "Oude Kerk official website". http://www.oudekerk.nl/. Retrieved June 10, 2009.

- ^ "Houten Huys" (in Dutch). Archived from the original on December 26, 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20071226022822/http://www.bmz.amsterdam.nl/adam/nl/huizen/beg34.html. Retrieved May 19, 2008.

- ^ "Amsterdamse renaissance in de stijl van Hendrick de Keyser" (in Dutch). Archived from the original on November 27, 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20071127014006/http://www.bmz.amsterdam.nl/adam/nl/renaiss3.html. Retrieved May 19, 2008.

- ^ "Hollands Classicisme" (in Dutch). Archived from the original on February 2, 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20070202200016/http://www.bmz.amsterdam.nl/adam/nl/holclass.html. Retrieved May 21, 2008.

- ^ "Neo-stijlen" (in Dutch). Archived from the original on August 19, 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20070819204630/http://www.bmz.amsterdam.nl/adam/nl/neostijl.html. Retrieved May 19, 2008.

- ^ "Amsterdamse School" (in Dutch). Archived from the original on October 27, 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20071027144316/http://www.bmz.amsterdam.nl/adam/nl/aschool.html. Retrieved May 21, 2008.

- ^ "Stadsdeel Amsterdam-Noord: Who governs Amsterdam-Noord?". Web.archive.org. November 18, 2007. Archived from the original on November 18, 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20071118012332/http://www.noord.amsterdam.nl/smartsite.dws?id=16213. Retrieved October 10, 2010.

- ^ a b c d "Gemiddelde bevolking per regio naar leeftijd en geslacht". Statistics Netherlands. http://statline.cbs.nl/StatWeb/Table.asp?PA=70233ned&D1=0-2,18-20&D2=39,66,88,126,312&D3=0&D4=(l-11)-l&DM=SLNL&LA=nl. Retrieved October 4, 2007.

- ^ "Indeling van Nederland in 40 COROP-gebieden" (PDF). Statistics Netherlands. http://www.cbs.nl/NR/rdonlyres/F40C0A58-7E1E-4BD5-93B3-F050153117B3/0/2006cr.pdf. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- ^ "Previous versions of the constitution" (in (Dutch)). Nl.wikisource.org. http://nl.wikisource.org/wiki/Nederlandse_grondwet. Retrieved October 10, 2010.

- ^ "Amsterdam – Economische Zaken" (in Dutch). http://www.ez.amsterdam.nl/page.php?menu=24&page=6. Retrieved May 22, 2008.

- ^ "European Cities Monitor 2007" (in Dutch). I Amsterdam. Archived from the original on January 8, 2008. http://web.archive.org/web/20080108130938/http://www.iamsterdam.com/press_room/press_releases_0/2007/european_cities. Retrieved 11 June 2008.

- ^ "Zuidas" (in Dutch). Archived from the original on December 24, 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20071224035945/http://www.zuidas.nl/smartsite.dws?id=1044&curindex=2. Retrieved May 22, 2008.

- ^ "Rembrandt Tower". http://www.emporis.com/en/wm/ci/bu/sk/li/?id=100759&bt=2&ht=2&sro=0. Retrieved May 22, 2008.

- ^ "Philips" (in Dutch). http://www.philips.nl/about/index.page. Retrieved May 22, 2008.

- ^ "Key Figures Amsterdam 2009: Tourism". City of Amsterdam Department for Research and Statistics. 2009. http://www.os.amsterdam.nl/tabel/13871/. Retrieved September 30, 2009.

- ^ a b c Fedorova, T and Meijer, R (January 2007). "Toerisme in Amsterdam 2006/2007" (in Dutch) (PDF). http://www.os.amsterdam.nl/pdf/2008_toerisme_in_amsterdam.pdf. Retrieved May 22, 2008.

- ^ DutchAmsterdam.nl (2011 [last update]). "Amsterdam remains opposed to coffeeshops membership system". dutchamsterdam.nl. http://www.dutchamsterdam.nl/1957-amsterdam-remains-opposed-to-coffeeshops-membership-system. Retrieved July 13, 2011.

- ^ "Half of young big-city dwellers have non-western background". Cbs.nl. http://www.cbs.nl/en-GB/menu/themas/bevolking/publicaties/artikelen/archief/2006/2006-1995-wm.htm?RefererType=Favorite. Retrieved October 10, 2010.