- Politics of the Netherlands

-

Netherlands

This article is part of the series:

Politics and government of

the NetherlandsConstitutionCabinetDecentralized gov'tForeign policyRelated subjects

Life in the Netherlands  Government

GovernmentThe politics of the Netherlands take place within the framework of a parliamentary representative democracy, a constitutional monarchy and a decentralised unitary state.[1] The Netherlands is described as a consociational state.[2] Dutch politics and governance are characterised by a common striving for broad consensus on important issues, within both the political community and society as a whole.[1]

Contents

Constitution

Main article: Constitution of the NetherlandsThe constitution lists the basic civil and social rights of the Dutch citizens and it describes the position and function of the institutions that have executive, legislative and judiciary power.

It should be noted that the constitution of the Netherlands is only applicable in the European part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. The Kingdom as a whole has its own Statute, describing its federate political system which also includes the Caribbean islands of Aruba, Curaçao and Sint Maarten and Caribisch Nederland, the islands Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba.

The Netherlands do not have a Constitutional Court and judges do not have the authority to review laws on their constitutionality. International treaties and the Statute of the Kingdom, however, overrule Dutch law and the constitution and judges are allowed to review laws against these in a particular court case. Furthermore all legislation that is not a law in the strict sense of the word (such as policy guidelines or laws proposed by provincial or municipal government) can be tested on their constitutionality.

Amendments to the constitution must be approved by both Houses of the States-General (Staten Generaal) twice. The first time around, this requires a simple majority of fifty percent plus one vote. After parliament has been dissolved and general elections are held, both Houses must approve the proposed amendments with a two thirds majority.

Political institutions

Major political institutions are the monarchy, the cabinet, the States General (parliament) and the judicial system. There are three other High Colleges of state, which stand on equal foot with parliament but have a less political role, of which the Council of State is the most important. Other levels of government are the municipalities, the waterboards and the provinces. Although not mentioned in the constitution, political parties and the social partners organised in the Social Economic Council are important political institutions as well.

It is important to realise that the Netherlands does not have a traditional separation of powers: according to the constitution the States-General and the government (the Queen and cabinet) share the legislative power. All legislation has to pass through the Council of State (Dutch: Raad van State) for advice and the social-economic council advises the government on most social-economic legislation. The executive power is reserved for government. Note however that the Social-Economic Council has the special right to make and enforce legislation on several sectors, mostly in agriculture. The judicial power is divided into two separate systems of courts. For civil and criminal law the independent Hoge Raad is the highest court. For administrative law the Raad van State is the highest court, which is ex officio chaired by the Queen.

Monarchy

Main article: Dutch MonarchyThe Netherlands has been a monarchy since March 16, 1815, and has been governed by members of the House of Orange-Nassau ever since.

The present monarchy was originally founded in 1813. After the expulsion of the French, the Prince of Orange was proclaimed Sovereign Prince of The Netherlands. The new monarchy was confirmed in 1815 at the Congress of Vienna as part of the re-arrangement of Europe after the fall of Napoleon Bonaparte. The House of Orange-Nassau were given the present day Netherlands and Belgium to govern as the United Kingdom of the Netherlands. Between 1815 and 1890, the King of the Netherlands was also Grand Duke of Luxembourg.

The current monarch is Beatrix of the Netherlands. The heir apparent is Willem-Alexander, her son.

Beatrix of the Netherlands, the current Dutch monarch

Beatrix of the Netherlands, the current Dutch monarch

Constitutionally, the Queen is head of state and has a role in the formation of government and in the legislative process. She has to co-sign every law to make it valid. The monarch is also ex officio chair of the Council of State, which advises the cabinet on every piece of legislation and is the final court for administrative law. Although the Queen takes these functions seriously, she refrains from exerting her power in these positions. The Queen also plays a central role in the formation of a cabinet after general elections or a cabinet crisis. Since coalition cabinets of two or more parties are the rule, this process has influence on government policy for years to come. She appoints the (in)formateur, who chairs the formation talks, after consulting the leaders of all parties represented in parliament. When the formation talks have been concluded the Queen appoints the cabinet. Because this advice is a matter of public record, the Queen can not easily take a direction which is contrary to the advice of a majority in parliament. On the other hand, what is actually talked about behind the closed doors of the palace is not known. When a cabinet falls, the prime minister has to request the Queen to dismiss the cabinet.

Cabinet

Main article: Cabinet of the NetherlandsThe government of the Netherlands constitutionally consists of the queen and the cabinet ministers. The Queen's role is limited to the formation of government and she does not actively interfere in daily decision-making. The ministers together form the Council of Ministers. This executive council initiates laws and policy. It meets every Friday in the Trêveszaal at the Binnenhof. While most of the ministers head government ministries, since 1939 it has been permissible to appoint ministers without portfolio.

Political parties

Main article: Political parties of the NetherlandsThe system of proportional representation, combined with the historical social division between Catholics, Protestants, Socialists and Liberals has resulted in a multiparty system. The major political parties are CDA, PvdA, SP and VVD. The parties currently represented in the Dutch House of Representatives are:

- Christian Democratic Appeal (CDA), a centre-right Christian Democratic party. It holds to the principle that government activity should supplement but not supplant communal action by citizens. The CDA puts its philosophy between the "individualism" of the VVD and the "statism" of the PvdA.

- The Labour Party (PvdA), a social democratic, centre-left Labour party. Its programme is based on greater social, political, and economic equality for all citizens.

- The Party for Freedom (PVV), an anti-Islam conservative-liberal party founded and dominated by Geert Wilders, formerly of the VVD. Its philosophy is based on free market economics and opposition to immigration and European integration.

- The Socialist Party (SP), in its first years a radical socialist/communist party, a Maoist split from the Communist Party Netherlands, is now a more mainstream socialist party, left from the PvdA on economic issues but at the same time taking more conservative positions on issues like integration and national identity than the PvdA.

- The People's Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD), a conservative liberal party. It attaches great importance to private enterprise and the freedom of the individual in political, social, and economic affairs.

- Democrats 66 (D66), a Social-Liberal party. The party supports liberal policies on abortion and euthanasia and reform of the welfare state. The party is left-wing on immigration and foreign policy. And Right-wing on economics and environment

- Green Left (GroenLinks) combines, as its name implies green environmentalist ideals with left-wing ideals. The party is also strongly in favour of the multicultural society.

- Christian Union (ChristenUnie), a Christian-democratic party made up by mostly orthodox Protestant Christians, with conservative stances on abortion, euthanasia and gay marriage. In other areas the party is considered centre-left, for instance on immigration, welfare state and environment.

- The Party for the Animals is a single-issue animal rights party with natural affinity for environmental issues. In general, the party is considered left of the centre.

- The Political Reformed Party (SGP), the most orthodox Protestant party with conservative policies: government is only to serve God. It is a testimonial party. Only in 2006 and after heavy political pressure were women allowed to be members of this party.

The following table details the party representation in the Dutch parliament. The political leaders mentioned are not necessarily also leader of the parliamentary parties in the House of Representatives.

Parties Political Leader Votes (2010) HoR seats Senate seats People's Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD) Mark Rutte 1,929,575 31 16 Labour Party (PvdA) Job Cohen 1,848,805 30 14 Party for Freedom (PVV) Geert Wilders 1,454,493 24 10 Christian Democratic Appeal (CDA) Maxime Verhagen 1,281,886 21 11 Socialist Party (SP) Emile Roemer 924,696 15 8 Democrats 66 (D66) Alexander Pechtold 654,167 10 5 GreenLeft (GL) Jolande Sap 628,096 10 5 ChristianUnion (CU) Arie Slob 305,094 5 2 Political Reformed Party (SGP) Kees van der Staaij 163,581 2 1 Party for Animals (PvdD) Marianne Thieme 122,317 2 1 50PLUS (50+) Jan Nagel did not compete 0 1 Independent Senate Fraction (OSF) Kees de Lange* did not compete 0 1 Total (includes Others and Blank/Invalid; turnout 75.4%) 9,442,977 150 75 Council of State

Prime Minister Abraham Kuyper (1901-1905)

Prime Minister Abraham Kuyper (1901-1905)

Prime Minister Pieter Cort van der Linden (1913-1918)

Prime Minister Pieter Cort van der Linden (1913-1918)

Prime Minister Hendrikus Colijn (1925-1926; 1933-1939)

Prime Minister Hendrikus Colijn (1925-1926; 1933-1939)

Prime Minister Willem Drees (1948-1958)

Prime Minister Willem Drees (1948-1958)

Prime Minister Piet de Jong (1967-1971)

Prime Minister Piet de Jong (1967-1971)

Prime Minister Joop den Uyl (1973-1977)

Prime Minister Joop den Uyl (1973-1977)

Prime Minister Ruud Lubbers (1982-1994)

Prime Minister Ruud Lubbers (1982-1994)

Prime Minister Wim Kok (1994-2002)

Prime Minister Wim Kok (1994-2002)

Prime Minister Mark Rutte (2010-)

Prime Minister Mark Rutte (2010-) Main article: Dutch Council of State

Main article: Dutch Council of StateThe Council of State is an advisory body of cabinet on constitutional and judicial aspects of legislature and policy. All laws proposed by the cabinet have to be sent to the Council of State for advice. Although the advice is not binding, the cabinet is required to react to the advice and it often plays a significant role in the ensuing debate in Parliament. In addition the Council is the highest administrative court.

The Council is ex officio chaired by the Monarch. The probable heir to the throne becomes a member of the Council when reaching legal adulthood. The Monarch leaves daily affairs to the vice-chair of the Council, Herman Tjeenk Willink and the other councillors, who are mainly legal specialists, former ministers, members of parliament and judges or professors of law.

High Colleges of State

The Dutch political system has five so called the High Colleges of State, which are explicitly regarded as independent by the Constitution. Apart from the two Houses of Parliament and the Council of State, these are the Netherlands Court of Audit and the Nationale Ombudsman (National Ombudsman).

The Court of Audit investigates whether public funds are collected and spent legitimately and effectively. The National Ombudsman investigates complaints about the functioning and practices of government. As with the advice of the Council of State, the reports from these organizations are not easily put aside and often play a role in public and political debate.

Judicial system

The judiciary comprises 19 district courts, five courts of appeal, two administrative courts (Centrale Raad van Beroep and the College van beroep voor het bedrijfsleven) and a Supreme Court (Hoge Raad) which has 24 justices. All judicial appointments are made by the Government. Judges nominally are appointed for life but actually retire at age 70. The Council of State functions as the highest court in most administrative cases.

Advisory Councils

As part of the Dutch tradition of depoliticized consensus decision making, the government often makes use of advisory councils composed out of academic specialists or stake holders.

The most prominent advisory council is the Social-Economic Council (Sociaal Economische Raad, SER). It is composed of trade unions, employers' organizations and government-appointed specialists. It is consulted at an early stage in financial, economic and social policymaking. It advises government and its advice, just like the advice of the High Colleges of State, cannot easily be set aside. The SER heads a system of PBOs, self-regulating organizations that can make laws for specific economic sectors.

The following organizations are represented in the Social-Economic Council: the leftwing trade union FNV, the Christian trade union CNV and the trade union for managerial staff MHP, the employers' organization VNO-NCW, the employers' organization for small and mediumsized enterprises MKB-Nederland, and the employers' organization for farmers LTO Nederland. One third of the members of the council are appointed by the government. These include professors of Economics and related fields as well as representatives of the Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis and De Nederlandsche Bank. In addition, representatives of environmental and consumers' organizations are represented in SER working groups.

Other prominent advisory councils are the Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis, which forecasts economic development; the Statistics Netherlands which studies social and economic developments; the Social and Cultural Planning Office, which studies long term social and cultural trends; the Netherlands National Institute for Public Health and the Environment which advises the government on environmental and health issues; and the Scientific Council for Government Policy, which advises the government on long term social, political and economic trends.

Subnational government

Main articles: Provincial politics in the Netherlands and Municipal Politics of the NetherlandsRegional government in the Netherlands is formed by twelve provinces. Provinces are responsible for spatial planning, health policy and recreation, within the bounds prescribed by the national government. Furthermore they oversee the policy and finances of municipalities and waterboards. The executive power is in hands of the Queen's Commissioner and the College of the Gedeputeerde Staten. The Queen's Commissioner is appointed by the national Cabinet and responsible to the Minister of the Interior and Kingdom Relations. Members of the Gedeputeerde Staten are appointed by, and responsible to the provincial legislature, the States Provincial, which is elected by direct suffrage.

Local government in the Netherlands is formed by 418 municipalities. Municipalities are responsible for education, spatial planning and social security, within the bounds prescribed by the national and provincial government. They are governed by the College of Mayor and Aldermen. The Mayor is appointed by the national Cabinet and responsible to the Minister of the Interior and Kingdom Relations. The Aldermen are appointed by, and responsible to the Municipal Council, which is elected by direct suffrage. Local government on the Caribbean Netherlands is formed by three public bodies sometimes called special municipalities who do not fall within a province. They are governed by a Lieutenant-general (Dutch: gezaghebber) and "eilandgedeputeerden" which are responsible to the island council, which is elected by direct suffrage. Their activities are similar but wider than to municipalities.

The major cities of Amsterdam and Rotterdam are subdivided into administrative areas (stadsdelen), which have their own (limited) responsibilities.

Furthermore there are waterboards which are responsible for the country's polders, dikes and other waterworks. These bodies are elected in non-partisan elections and have the power to tax their residents.

Policy

Foreign policy

Main article: Foreign relations of the NetherlandsThe foreign policy of the Netherlands is based on four basic commitments: to Transatlantic relations, European integration, international development and international law. While historically the Netherlands used to be a neutral state, it has joined many international organisations since the Second World War. Most prominently the UN, NATO and the EU. The Dutch economy is very open and relies on international trade. One of the more controversial international issues surrounding the Netherlands is its liberal policy towards soft drugs and its position as one of the major exporters of hard drugs[citation needed].

Policy issues

Dutch policies on recreational drugs, prostitution, same-sex marriage, abortion and euthanasia are among the most liberal in the world.

Political history

Main article: History of the Netherlands: modern history (1900-present)- For an overview of the history of the most important political currents, see Christian democracy in the Netherlands, Socialism in the Netherlands and Liberalism in the Netherlands.

1800–1966

The Netherlands has been a constitutional monarchy since 1815 and a parliamentary democracy since 1848; before that it had been a republic from 1581 to 1806 and a kingdom between 1806 and 1810 (it was part of France between 1810 and 1813).

Before 1917, the Netherlands had a first past the post single seat system with census suffrage (per the constitution of 1814), in which only property-owning adult males had the right to vote. Under influence of the rising socialist movement the requirements were gradually reduced until in 1917 the present voting system of a representative democracy with male universal suffrage was instituted, expanded in 1919 to include women.

Until 1966, Dutch politics were characterised by pillarisation: society was separated in several segments (pillars) which lived separate from each other and there was only contact at the top levels, in government. These pillars had their own organisations, most importantly the political parties. There were four pillars, which provided the five most important parties, the socialist Labour Party (Partij van de Arbeid; PvdA), the conservative-liberal People's Party for Freedom and Democracy (Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie; VVD), the Catholic Catholic People's Party (Katholieke Volkspartij; KVP) and the two conservative-Protestant parties, the Christian Historical Union (Chirstelijk Historische Unie; CHU) and the Anti Revolutionary Party (Anti-Revolutionaire Party; ARP). Since no party ever gained an absolute majority, these political parties had to work together in coalition governments. These alternated between a centre left, Rooms Rood, coalition of PvdA, KVP, ARP and CHU and a centre right coalition of VVD, KVP, ARP and CHU.

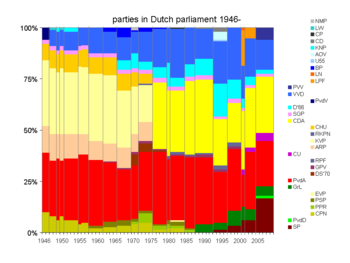

This figure shows the seat distribution in the Dutch House of Representatives from the first general elections after the Second World War (1946), to the current situation. The left wing parties are on the bottom, the Christian-democratic parties in the center, with the right wing parties closer to the top. Occasionally one issue parties have arisen that are shown at the extreme top. Vertical lines indicate general elections.

This figure shows the seat distribution in the Dutch House of Representatives from the first general elections after the Second World War (1946), to the current situation. The left wing parties are on the bottom, the Christian-democratic parties in the center, with the right wing parties closer to the top. Occasionally one issue parties have arisen that are shown at the extreme top. Vertical lines indicate general elections.

1966–1994

In the 1960s, new parties appeared, which were mostly popular with young voters, who felt less bound to the pillars. The post-war babyboom meant that there had been a demographic shift to lower ages. On top of that, the voting age was lowered, first from 23 to 21 years in 1963 and then to 18 years in 1972. The most successful new party was the progressive-liberal D66, which proposed democratisation to break down pillarisation. Pillarisation indeed declined, with the three Christian-democratic parties losing almost half of their votes. In 1977 they formed the Christian-democratic CDA, which became a major force in Dutch politics, participating in governments from 1977 until 1994. Meanwhile the conservative-liberal VVD and progressive-liberal D66 made large electoral gains.

The Dutch welfare state had become the most extensive social security system in the world by the early eighties. But the welfare state came into crisis when spending rose due to dramatic high unemployment rates and poor economic growth. The early eighties saw unemployment rise to over 11% and the budget deficit rose to 10.7% of the National Income. The centre-right and centre-left coalitions of CDA-VVD and CDA-PvdA reformed the Dutch welfare state to bring the budget deficit under control and to create jobs. Social benefits were reduced, taxes lowered and businesses deregulated. Gradually the economy recovered and the budget deficit and unemployment were reduced considerably.

When the far-left parties lost much electoral support in the 1986 elections, they decided to merge into the new GreenLeft (GroenLinks) in 1989, with considerable success.

1994–present

In the 1994 general election the Christian-democratic CDA lost nearly half its seats. The social-liberal D66, on the other hand, doubled their size. For the first time in eighty years a coalition was formed without the Christian-democrats. The Purple Coalition was formed between PvdA, D66 and VVD. The colour purple symbolised the mixing of socialist red with liberal blue. During the Purple years, which lasted until 2002, the government introduced legislation on abortion, euthanasia and gay marriage. The Purple coalition also marked a period of remarkable economic prosperity.

The Purple coalition parties together lost their majority in the 2002 elections due to the rise of Pim Fortuyn List, the new political party led by the flamboyant populist Pim Fortuyn. He campaigned on an anti-immigration programme and spoke of the "Purple Chaos" (Dutch: "Puinhopen van Paars"). Fortuyn was shot dead a week before the elections took place. In the elections the LPF entered parliament with one sixth of the seats, while the PvdA (Labour) lost half its seats. A cabinet was formed by CDA, VVD and LPF, led by Prime Minister Jan Peter Balkenende. It proved short-lived: after only 87 days in power, the coalition fell apart as a result of consecutive conflicts within the LPF and between LPF ministers.

In the ensuing elections in January 2003, the LPF dropped to only five percent of the seats in the House of Representatives. The left-wing Socialist Party (Socialistische Partij; SP) led by Jan Marijnissen became the fourth party of the Netherlands. The centre-right Balkenende II cabinet was formed by the Christian-democratic CDA, the conservative-liberal VVD and the progressive-liberal D66. Against popular sentiment, the right-wing coalition initiated an ambitious programme of welfare state reforms, health care privatisation and stricter immigration policies. On June 1, 2005, the Dutch electorate voted in a referendum against the proposed European Constitution by a majority of 62%, three days after the French had also rejected the treaty.

In June 2006, D66 withdrew its support for the coalition in the aftermath of the upheaval about the asylum procedure of Ayaan Hirsi Ali instigated by the Dutch immigration minister Verdonk. The coalition collapsed as a result and the Balkenende III caretaker cabinet was formed by CDA and VVD. The ensuing general elections that were held on 22 November 2006 saw a major advance for the Socialist Party, which almost tripled in size and became the third largest party with 17% of the seats, while the moderate PvdA (Labour Party) lost a quarter of its seats. At the other end of the spectrum LPF lost all its seats, while the new anti-immigrant PVV went from nothing to 6% of the seats, becoming the fifth biggest party. This polarisation of the House of Representatives, with an even distribution between left and right made the formation negotiations very difficult. The talks resulted in the formation of the social-Christian fourth cabinet Balkenende by the PvdA, the CDA and the ChristianUnion, this cabinet is oriented at solidarity, durability and normen en waarden.

In February 2010, the PvdA withdrew its support for the fourth cabinet Balkenende, due to the party disagreeing with the CDA and the ChristianUnion about whether to prolong the Dutch military involvement in the War in Afghanistan. In the following 2010 general election, the conservative-liberal VVD became the biggest party with 31 seats, followed closely by the PvdA with 30 seats. The right-wing PVV went from 9 to 24 seats, while the CDA lost half of their support and won 21 seats. The Socialist Party lost 10 of its 25 seats, and both D66 and GL won 10 seats. The ChristianUnion, the smallest coalition party, lost 1 of their 6 seats. Both the SGP and the PvdD kept their 2 seats. The following cabinet formation eventually resulted in the Rutte cabinet, a minority government formed by VVD and CDA, supported in parliament by the PVV to gain a majority.

External links

- The official site of the Dutch government

- (Dutch) Parlement.com, detailed information about politicians elections, cabinets, parties, etc., since 1814.

References

- ^ a b Civil service systems in Western Europe edited by A. J. G. M. Bekke, Frits M. Meer, Edward Elgar Publishing, 2000, Chapter 7

- ^ McGarry, John; O'Leary, Brendan (1993). "Introduction: The macro-political regulation of ethnic conflict". In McGarry, John and O'Leary, Brendan. The Politics of Ethnic Conflict Regulation: Case Studies of Protracted Ethnic Conflicts. London: Routledge. pp. 1–40. ISBN 041507522X.

Politics of Europe Sovereign

states- Albania

- Andorra

- Armenia

- Austria

- Azerbaijan

- Belarus

- Belgium

- Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Bulgaria

- Croatia

- Cyprus

- Czech Republic

- Denmark

- Estonia

- Finland

- France

- Georgia

- Germany

- Greece

- Hungary

- Iceland

- Ireland

- Italy

- Kazakhstan

- Latvia

- Liechtenstein

- Lithuania

- Luxembourg

- Macedonia

- Malta

- Moldova

- Monaco

- Montenegro

- Netherlands

- Norway

- Poland

- Portugal

- Romania

- Russia

- San Marino

- Serbia

- Slovakia

- Slovenia

- Spain

- Sweden

- Switzerland

- Turkey

- Ukraine

- United Kingdom

- (England

- Northern Ireland

- Scotland

- Wales)

- Vatican City

States with limited

recognition- Abkhazia

- Kosovo

- Nagorno-Karabakh

- Northern Cyprus

- South Ossetia

- Transnistria

Dependencies

and other territories- Åland

- Faroe Islands

- Gibraltar

- Guernsey

- Jan Mayen

- Jersey

- Isle of Man

- Svalbard

Other entities - European Union

Categories:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.