- Drug policy of the Netherlands

-

The drug policy of the Netherlands officially has four major objectives:

- To prevent recreational drug use and to treat and rehabilitate recreational drug users.

- To reduce harm to users.

- To diminish public nuisance by drug users (the disturbance of public order and safety in the neighbourhood).

- To combat the production and trafficking of recreational drugs.[1]

Most policymakers in the Netherlands believe that if a problem has proved to be unsolvable, it is better to try controlling it and reducing harm instead of continuing to enforce laws with mixed results. By contrast, most other countries take the point of view that recreational drug use is detrimental to society and must therefore be outlawed. This has caused friction between the Netherlands and other countries about the policy for cannabis, most notably with France and Germany. As of 2004, Belgium seems to be moving toward the Dutch model and a few local German legislators are calling for experiments based on the Dutch model. Switzerland has had long and heated parliamentary debates about whether to follow the Dutch model on cannabis, most recently deciding against it in 2004; currently a ballot initiative is in the works on the question. New law to come in shortly in 3 provinces first including mastricht and Eindhoven (covering other provinces including Amsterdam in 2012) only allowing registered members of clubs to go to the cannabis cafes, this will allow Germans, Belgians and Dutch in but will ban all other foreigners including these from EU states and is therefore discriminating within the EU which is illegal under European law. If seen to fruition which seems likely,the new laws will reduce tourism in Holland dramatically and cost the exchequer millions in lost revenue and well established business are forecast to go bankrupt. It also opens the door for other European nations with relaxed attitudes on cannabis to capitalise on the niche in the market and take the valuable tourist resource. In the last few years certain strains of cannabis with higher concentrations of THC and drug tourism have challenged the former policy in the Netherlands and led to a more restrictive approach; for example, a ban on selling cannabis to tourists in coffeeshops suggested to start late 2011.[2][3][4] In October 2011 the Dutch government proposed a new law to the Dutch parliament, that will put cannabis with 15% THC] or more onto the list of hard drugs. If the law comes into effect, it would prohibit "coffe shops" from selling cannabis of that potency. The government finds motivation from its experts' assertions, that cannabis of that strength have an "unacceptable risk" associated with its usage. Today, about 80 % of the "coffe shops" sell, among their products, such kind of cannabis [5]

While the legalization of cannabis remains controversial, the introduction of heroin-assisted treatment in 1998 has been lauded for considerably improving the health and social situation of opiate-dependent patients in the Netherlands.[6] In 2010 research shows that the "heroin-junkies" have disappeared from the streets of the Netherlands and the treatment is upgraded from a test-trial to standard treatment for otherwise untreatable addicts. Also, the number of heroin addicts has dropped by more than 30% since 1983.[citation needed]

Contents

Public health

Large-scale dealing, production, import and export are prosecuted to the fullest extent of the law, even if it does not supply end users or coffeeshops with more than the allowed amounts. Exactly how coffeeshops get their supplies is rarely investigated, however. The average concentration of THC in the cannabis sold in coffeeshops has increased from 9% in 1998 to 18% in 2005.[7] This means that less plant material has to be consumed to achieve the same effect. One of the reasons is plant breeding and use of greenhouse technology for illegal growing of cannabis in Netherlands.[7] The former minister of Justice Piet Hein Donner announced in June 2007 that cultivation of cannabis shall continue to be illegal.

Non-enforcement

The drug policy of the Netherlands is marked by its distinguishing between so called "soft" and "hard drugs". An often used argument is that alcohol, which is claimed by some scientists as a hard drug,[8] is legal and a soft drug can't be more dangerous to society if it's controlled. This may refer to the Prohibition in the 1920s, when the U.S. government decided to ban all alcohol. Prohibition created a golden opportunity for organized crime syndicates to smuggle alcohol, and as a result the syndicates were able to gain considerable power in some major cities.[9]

Cannabis remains a controlled substance in the Netherlands and both possession and production for personal use are still misdemeanors, punishable by fines. Coffee shops are also technically illegal but are flourishing nonetheless. However, a policy of non-enforcement has led to a situation where reliance upon non-enforcement has become common, and because of this the courts have ruled against the government when individual cases were prosecuted.

This is because the Dutch Ministry of Justice applies a gedoogbeleid (tolerance policy) with regard to the category "soft drugs": an official set of guidelines telling public prosecutors under which circumstances offenders should not be prosecuted. This is a more official version of the common practice in other countries, in which law enforcement sets priorities as to which offenses are important enough to spend limited resources on.

According to current gedoogbeleid the possession of a maximum amount of five grams cannabis for personal use is not prosecuted. A maximum of five Cannabis sativa plants may be grown without prosecution, although they have to be handed over upon discovery.[10] (Dutch)

Proponents of gedoogbeleid argue that such a policy offers more consistency in legal protection in practice, than without it. Opponents of the Dutch drug policy either call for full legalization, or argue that laws should penalize morally wrong or decadent behavior, whether this is enforceable or not. In the Dutch courts, however, it has long been determined that the institutionalized non-enforcement of statutes with well defined limits constitutes de facto decriminalization. The statutes are kept on the books mainly due to international pressure and in adherence with international treaties.[11] A November 2008 poll showed that a 60% majority of the Dutch population support the legalisation of soft drugs. The same poll showed that 85% supported closing of all cannabis coffee shops within 250 meters walking distance from schools.[12]

Drug law enforcement

Importing and exporting of any classified drug is a serious offence. The penalty can run up to 12 to 16 years if it is hard drug trade, maximum 4 years for import or export of large quantities of cannabis.[13] It is prohibited to operate a motor vehicle while under the influence of any drug that affects driving ability in such an extent that you are unable to drive properly. (Section 8 of the 1994 Road Traffic Act section 1). The Dutch police have the right to do a drug test if they suspect this, for example on anybody involved in a traffic accident. Causing an accident, which inflicted bodily harm, under influence of any drug is seen as a crime that may be punished with up to 3 years in prison (9 years in case of a fatal accident). Suspension of driving license is also normal in such a case (maximum 5 years).[14] Schiphol, a large international airport near Amsterdam, has long practiced a zero tolerance policy for drugs for airline passengers. In 2006 there were 20,769 drug crimes registered by public prosecutors and 4,392 persons received an unconditional prison sentence[1] The rate of imprisonment for drug crimes is about the same as in Sweden, which has a zero tolerance policy for drug crimes.[15]

Despite the high priority given by the Dutch government to fighting illegal drug trafficking, the Netherlands continue to be an important transit point for drugs entering Europe, a major producer[16] and leading distributor of cannabis, heroin, cocaine, amphetamines[17][18] and other synthetic drugs, and a medium consumer of illicit drugs.[19] Despite the crackdown on traffic and illicit manufacture of temazepam by Interpol,[20] the country has also become a major exporter of illicit temazepam of the "jelly" variety, trafficking it to the United Kingdom and other European nations.[21] The Netherlands' special synthetic drug unit, set up in 1997 to coordinate the fight against designer drugs, appears to be successful.[citation needed] The government has intensified cooperation with neighbouring countries and stepped up border controls. In recent years, it also introduced so-called 100% checks and bodyscans at Schiphol Airport on incoming flights from Dutch overseas territories Aruba and Netherlands Antilles to prevent importing cocaine by means of swallowing balloons by mules.

Although drug use, as opposed to trafficking, is seen primarily as a public health issue, responsibility for drug policy is shared by both the Ministry of Health, Welfare, and Sports, and the Ministry of Justice.

The Netherlands spends more than €130 million annually on facilities for addicts, of which about fifty percent goes to drug addicts. The Netherlands has extensive demand reduction programs, reaching about ninety percent of the country's 25,000 to 28,000 hard drug users. The number of hard drug addicts has stabilized in the past few years and their average age has risen to 38 years, which is generally seen as a positive trend. Notably, the number of drug-related deaths in the country remains amongst the lowest in Europe.[22]

On 27 November 2003, the Dutch Justice Minister Piet Hein Donner announced that his government was considering rules under which coffeeshops would only be allowed to sell soft drugs to Dutch residents in order to satisfy both European neighbors' concerns about the influx of drugs from the Netherlands, as well as those of Netherlands border town residents unhappy with the influx of "drug tourists" from elsewhere in Europe. The European Court of Justice ruled in December 2010 that Dutch authorities can ban coffee shops from selling marijuana to foreigners. The EU court said the southern Dutch city of Maastricht was within its rights when it introduced a "weed passport" in 2005 to prevent foreigners from entering cafes that sell marijuana.[23]

In 2010 the owner of Netherlands's largest cannabis selling coffee shop was fined 10 million euros for breaking drug laws by keeping more than the tolerated amount of cannabis in the shop. He was also sentenced to a 16 week prison term.[24]

Results of the drug policy

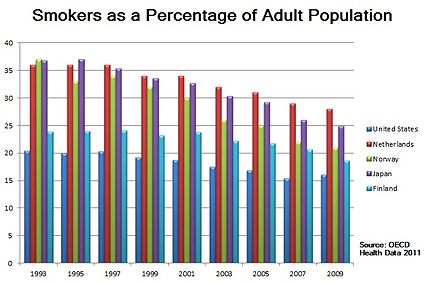

In the Netherlands 9.5% of young adults (aged 15–34) consume soft drugs once a month, comparable to the level of Finland (8%), Latvia (9,7%) and Norway (9.6%) and less than in the UK (13.8%), Germany (11,9%), Czech Republic (19,3%), Denmark (13,3%), Spain (18.8%), France (16,7%), Slovakia (14,7%) and Italy (20,9%) but higher than in Bulgaria (4,4%), Sweden (4,8%), Poland (5,3%) or Greece (3,2%).[25][26] The monthly prevalence of drugs other than cannabis among young people (15-24) was 4% in 2004, that was above the average (3%) of 15 compared countries in EU. However, seemingly few transcend to becoming problem drug users (0.30%), well below the average (0.52%) of the same compared countries.[26]

The reported number of deaths linked to the use of drugs in the Netherlands, as a proportion of the entire population, is together with Poland, France, Slovakia, Hungary and the Czech Republic the lowest of the EU.[27] The Dutch government is able to support approximately 90% of help-seeking addicts with detoxification programs. Treatment demand is rising.[28]

Criminal investigations into more serious forms of organized crime mainly involve drugs (72%). Most of these are investigations of hard drug crime (specifically cocaine and synthetic drugs) although the number of soft drug cases is rising and currently accounts for 69% of criminal investigations.[28]

Implications of international law

The Netherlands is a party to the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, the 1971 Convention on Psychotropic Substances, and the 1988 United Nations Convention Against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances. The 1961 convention prohibits cultivation and trade of naturally-occurring drugs such as cannabis; the 1971 treaty bans the manufacture and trafficking of synthetic drugs such as barbiturates and amphetamines; and the 1988 convention requires states to criminalize illicit drug possession:

- Subject to its constitutional principles and the basic concepts of its legal system, each Party shall adopt such measures as may be necessary to establish as a criminal offence under its domestic law, when committed intentionally, the possession, purchase or cultivation of narcotic drugs or psychotropic substances for personal consumption contrary to the provisions of the 1961 Convention, the 1961 Convention as amended or the 1971 Convention.

The International Narcotics Control Board typically interprets this provision to mean that states must prosecute drug possession offenses. The conventions clearly state that controlled substances are to be restricted to scientific and medical uses. However, Cindy Fazey, former Chief of Demand Reduction for the United Nations Drug Control Programme, believes that the treaties have enough ambiguities and loopholes to allow some room to maneuver. In her report entitled The Mechanics and Dynamics of the UN System for International Drug Control, she notes:

- Many countries have now decided not to use the full weight of criminal sanctions against people who are in possession of drugs that are for their personal consumption. The Conventions say that there must be an offence under domestic criminal law, it does not say that the law has to be enforced, or that when it is what sanctions should apply. . . . Despite such grey areas latitude is by no means unlimited. The centrality of the principle of limiting narcotic and psychotropic drugs for medical and scientific purposes leaves no room for the legal possibility of recreational use. . . . Nations may currently be pushing the boundaries of the international system, but the pursuit of any action to formally legalize non-medical and non-scientific drug use would require either treaty revision or a complete or partial withdrawal from the current regime.

The Dutch policy of keeping anti-drug laws on the books while limiting enforcement of certain offenses is carefully designed to reduce harm while still complying with the letter of international drug control treaties. This is necessary in order to avoid criticism from the International Narcotics Board, which historically has taken a dim view of any moves to relax official drug policy. In their annual report, the Board has criticised many governments, including Canada, for permitting the medicinal use of cannabis, Australia for providing injecting rooms and the United Kingdom for proposing to downgrade the classification of cannabis,[29] which it has since done (although this change was reversed by the home secretary on 7 May 2008 against the advice of it's own commissioned report)

Recent developments

The liberal drug policy of the authorities in The Netherlands especially led to problems in "border hot spots" that attracted "drug tourism" as well as trafficking and related law enforcement problems in towns like Enschede in the East and Terneuzen, Venlo, Maastricht and Heerlen in the South. In 2006, Gerd Leers, then mayor of the border city of Maastricht, on the Dutch-Belgian border, criticised the current policy as inconsistent, by recording a song with the Dutch punk rock band De Heideroosjes. By allowing possession and retail sales of cannabis, but not cultivation or wholesale, the government creates numerous problems of crime and public safety, he alleges, and therefore he would like to switch to either legalising and regulating production, or to the full repression that his party (CDA) officially advocates. The latter suggestion has widely been interpreted as rhetorical.[30] Leers's comments have garnered support from other local authorities and put the cultivation issue back on the agenda.

In November 2008, Pieter van Geel, the leader of the CDA (Christian Democrats) in the Dutch parliament, called for a ban on the cafes where marijuana is sold. He said the practice of allowing so-called coffee shops to operate had failed. The CDA had the support of its smaller coalition partner, the CU (ChristenUnie), but the third party in government, PvdA (Labour), opposed. The coalition agreement worked out by the three coalition parties in 2007 stated that there would be no change in the policy of tolerance. Prominent CDA member Gerd Leers spoke out against him: cannabis users who now cause no trouble would be viewed as criminals if an outright ban was to be implemented. Van Geel later said that he respected the coalition agreement and would not press for a ban during the current government's tenure .[31]

By 2009, 27 coffee shops selling cannabis in Rotterdam, all within 200 metres from schools, must close down. This is nearly half of the coffee shops that currently operate within its municipality. This is due to the new policy of city mayor Ivo Opstelten and the town council.[32] The higher levels of the active ingredient in cannabis in Netherlands create a growing opposition to the traditional Dutch view of cannabis as a relatively innocent soft drug,.[33] Supporters of coffee shops state that such claims are often exaggerated and ignore the fact that higher content means a user needs to use less of the plant to get the desired effects, making it in effect safer.[34] Dutch research has however shown that an increase of THC content also increase the occurrence of impaired psychomotor skills, particularly among younger or inexperienced cannabis smokers, who do not adapt their smoking-style to the higher THC content.[35] Closing of coffeeshops is not unique for Rotterdam. Many other towns have done the same in the last 10 years.

In 2008, the municipality of Utrecht imposed a Zero Tolerance Policy to all events like the big dance party Trance Energy held in Jaarbeurs. However, such zero-tolerance policy at dance parties are now becoming common in the Netherlands and are even stricter in cities like Arnhem.

The two towns Roosendaal and Bergen op Zoom announced in October 2008 that they would start closing all coffee shops, each week visited by up to 25000 French and Belgian drug tourists, with closures beginning in February 2009.[36][37]

In May 2011 the Dutch government announced that tourist are to be banned from Dutch coffee shops, starting in the southern provinces and at the end of 2011 in the rest of the country.

- "In order to tackle the nuisance and criminality associated with coffee shops and drug trafficking, the open-door policy of coffee shops will end," (the Dutch health and justice ministers in a letter to the Dutch parliament)[2]

A government committee delivered in June 2011 a report about Cannabis to the Dutch government. It includes a proposal that cannabis with more than 15 percent THC should be labeled as hard drugs.[38] Higher concentrations of THC and drug tourism have challenged the current policy and led to a re-examination of the current approach; for eg. ban of all sales of cannabis to tourists in coffee shops from end of 2011 was proposed but currently only the border city of Maastricht has adopted the measure in order to test out its feasibility. [39] According to the initial measure, starting in 2012, each coffee shop was to operate like a private club with some 1,000 to 1,500 members. In order to qualify for a membership card, applicants would have to be adult Dutch citizens, membership was only to be allowed in one club. [4]

Bill banning "Magic mushrooms"

In October 2007, the prohibition of hallucinogenic or "magic mushrooms" was announced by the Dutch authorities.[40][41]

On April 25, 2008, the Dutch government, backed by a majority of members of parliament, decided to ban cultivation and use of all magic mushrooms. Amsterdam mayor Job Cohen proposed a three day cooling period in which clients would be informed three days before actually procuring the mushrooms and if they would still like to go through with it they could pick up their spores from the smart shop.[42][43] The ban has been considered a retreat from liberal drug policies.[44] This followed a few deadly incidents mostly involving tourists.[45] These deaths were not directly caused by the use of the drug per se, but by deadly accidents occurring while under the influence of magic mushrooms.

As of December 1, 2008, all psychedelic mushrooms are banned.[46] However, schlerotia (what are termed as "truffles"), mushroom spores, and active mycellium cultures remained legal and are readily available in the "smartshops", the stores in the Dutch cities that sell legal drugs, herbs and related gadgets.

Supply control

The relatively recent increase in the cocaine trafficking business has been largely focused on the Caribbean area. Since early 2003, a special law court with prison facilities has been operational at Schiphol airport. Since the beginning of 2005, there has been 100% control of all flights from key countries in the Caribbean. In 2004, an average of 290 drug couriers per month were arrested, decreasing to 80 per month by early 2006.[47]

See also

- Hollands Coffeeshop Database

- Drug liberalization

- Portugal 2001 decriminalization of drug use

- Drug policy of Portugal

- Drug policy of the Soviet Union

- Arguments for and against drug prohibition

- Designer drug

- Legality of cannabis by country

References

- ^ a b EMCDDA:National report 2007: Netherlands

- ^ a b Tourists Face Weed Ban In Dutch Coffee Shops, Sky News, May 28, 2011

- ^ If this policy became widespread, however, the drug tourism would cease to exist. "Dutch cannabis policy challenged". BBC News. 9 January 2006. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/4595018.stm. Retrieved 2008-07-09.

- ^ a b "Amsterdam Will Ban Tourists from Pot Coffee Shops". Atlantic Wire. May 27, 2011. http://www.theatlanticwire.com/global/2011/05/amsterdam-ban-pot-sales-tourists/38248/. Retrieved 2011-06-23.

- ^ Zware cannabis wordt harddrug, de Rijksoforheid voor Nederland, 2011

- ^ Heroin-assisted Treatment (HAT) a Decade Later: A Brief Update on Science and Politics. PMC 2219559. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2219559.

- ^ a b "Word Drug report, 2006, Chapter 2.3". Unodc.org. http://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/WDR-2006.html. Retrieved 2011-04-20.

- ^ "Alcohol, tobacco among riskiest drugs". MSNBC. 2007-03-24. http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/17760130/ns/health-addictions. Retrieved 2011-04-20.

- ^ "Call for end to distinction between soft and hard drugs". Nrc.nl. http://www.nrc.nl/international/article2061261.ece/Call_for_end_to_distinction_between_soft_and_hard_drugs. Retrieved 2011-04-20.

- ^ "Drugs | Rijksoverheid.nl". Justitie.nl. http://www.justitie.nl/onderwerpen/criminaliteit/drugs/softdrugs/. Retrieved 2011-04-20.

- ^ Marc Peeperkorn (22 April 2003). "Kamer voor legaliseren softdrugs" (in Dutch). Volkskrant. http://www.volkskrant.nl/den_haag/article164670.ece. Retrieved 31 January 2009. "To make the sale, trade and growth of softdrugs not punishable is currently hindered by United Nations treaties."

- ^ "Meeste Nederlanders voor legalisering softdrugs" (in Dutch). Het Parool. ANP. 21 November 2008. http://www.parool.nl/parool/nl/224/Binnenland/article/detail/47361/2008/11/21/Meeste-Nederlanders-voor-legalisering-softdrugs.dhtml. Retrieved 31 January 2009. "Two thirds of all Dutch advocate the legalisation of softdrugs."

- ^ "ELDD : Country profiles, Netherlands". Eldd.emcdda.europa.eu. http://eldd.emcdda.europa.eu/index.cfm?fuseaction=public.content&sLanguageISO=EN&nNodeID=5174. Retrieved 2011-04-20.

- ^ EMCDDA: Drugs and driving, page 9, June 2003[dead link]

- ^ The Swedish Prison and Probation Service in Basic Facts, 2007 page 20-21. Drugs/goods trafficking: 21,6% of a total number of 10,428 imprisoned in 2006.

- ^ "UNODC: Seizures laboratories, page 7" (PDF). http://www.unodc.org/pdf/research/wdr07/seizures_lab.pdf. Retrieved 2011-04-20.

- ^ "Report on Dutch drugs market submitted to the Lower House, 2004". English.justitie.nl. 2004-10-25. http://english.justitie.nl/currenttopics/pressreleases/achives2004/Report-on-Dutch-drugs-market-submitted-to-the-Lower-House.aspx. Retrieved 2011-04-20.

- ^ "World Drug report 2007, page 131". UNODC. http://www.unodc.org/unodc/index.html. Retrieved 2011-04-20.

- ^ Diagram with use of Cocaine per land

- ^ Interpol Annual Report - Temazepam

- ^ Bell, Alex (5 September 1999). "Deaths soar as Dutch drugs flood in". The Guardian (London). http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/1999/sep/05/theobserver.uknews6. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ^ "page 84". Emcdda.europa.eu. 2009-09-01. http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/html.cfm/index64151EN.html. Retrieved 2011-04-20.

- ^ EURAD: Dutch authorities can ban coffee shops from selling marijuana to foreigners[dead link]

- ^ "Dutch coffee shop fined 10m euros for breaking drug law, BBC,25 March 2010". BBC News. 2010-03-25. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/8587576.stm. Retrieved 2011-04-20.

- ^ "EMCDDA Annual Report 2009, ch 3 page 43". Emcdda.europa.eu. 2008-06-24. http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/html.cfm/index419EN.html. Retrieved 2011-04-20.

- ^ a b "Microsoft Word - Swedish drug control FINAL_14feb_merged.doc" (PDF). http://www.unodc.org/pdf/research/Swedish_drug_control.pdf. Retrieved 2011-04-20.

- ^ "EMCDDA: Mortality due to drug-related deaths in European countries". Emcdda.europa.eu. 2007-11-08. http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/stats07/drdtab05a. Retrieved 2011-04-20.

- ^ a b Trimbos Institute: Cannabis use stable, but treatment demand rising; National Drug Monitor Annual Report 2006 (19-06-2007) [dead link]

- ^ "aprile 2003". fuoriluogo.it. http://www.fuoriluogo.it/arretrati/2003/apr_17_en.htm. Retrieved 2011-04-20.

- ^ http://www.maastricht.nl/maastricht/show/id=160045

- ^ "More pressure on cannabis coffee shops". Nrc.nl. http://www.nrc.nl/international/article2055680.ece/More_pressure_on_cannabis_coffee_shops. Retrieved 2011-04-20.

- ^ View all comments that have been posted about this article. (2007-06-22). "Washington Post Changing Patterns in Social Fabric Test Netherlands". Washingtonpost.com. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/06/22/AR2007062202015_pf.html. Retrieved 2011-04-20.

- ^ Steeds meer tieners zoeken hulp voor wietverslaving 2007

- ^ Marijuana Myth Claim: potency has increased substantially http://www.erowid.org/plants/cannabis/cannabis_myth2.shtml

- ^ Tj. T. Mensinga et al. (PDF). A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, cross-over study on the pharmacokinetics and effects of cannabis. RIVM. http://www.rivm.nl/bibliotheek/rapporten/267002002.pdf. Retrieved 2007-09-21.

- ^ "AFP: Dutch towns close coffee shops in 'drug tourists' crackdown, Oct 24, 2008". Abc.net.au. 2008-10-24. http://www.abc.net.au/news/stories/2008/10/24/2400900.htm. Retrieved 2011-04-20.

- ^ "Selling soft drugs is not a right even in the Netherlands". Nrc.nl. http://www.nrc.nl/international/Features/article2035693.ece/Selling_soft_drugs_is_not_a_right_even_in_the_Netherlands. Retrieved 2011-04-20.

- ^ Garretsen: qualify strong cannabis as hard drugs, 2011-06-27

- ^ http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-15134669

- ^ "Dutch Declare Hallucinogenic Mushrooms Illegal". Washingtonpost.com. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/10/12/AR2007101202239.html. Retrieved 2011-04-20.

- ^ "Netherlands imposes total ban on 'magic' mushrooms". Independent.co.uk. 2007-10-13. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/netherlands-imposes-total-ban-on-magic-mushrooms-396774.html. Retrieved 2011-04-20.

- ^ (AFP) – Apr 25, 2008 (2008-04-25). "Afp.google.com, Netherlands to ban 'magic mushrooms'". Afp.google.com. http://afp.google.com/article/ALeqM5iEADgdtkZqEa5Fll7Vf4IMMhnhBg. Retrieved 2011-04-20.

- ^ "news.bbc.co.uk, Dutch bill to ban magic mushrooms". BBC News. 2008-04-26. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/7369431.stm. Retrieved 2011-04-20.

- ^ "Dutch Cabinet bans sale of hallucinogenic mushrooms in new retreat from liberal policies, Herald Tribune, October 12, 2007". International Herald Tribune. 2009-03-29. http://www.iht.com/articles/ap/2007/10/12/europe/EU-GEN-Netherlands-Magic-Mushrooms.php. Retrieved 2011-04-20.

- ^ "simplyamsterdam.nl, suicide after using hallucinating mushrooms". Simplyamsterdam.nl. 2007-03-27. http://www.simplyamsterdam.nl/news/French_tourist_in_Amsterdam_commits_suicide_after_using_magic_mushrooms.htm. Retrieved 2011-04-20.

- ^ Save The Mushroom Website

- ^ EMCDDA: Policies and laws[dead link]

Further reading

- Bewley-Taylor, David R. and Fazey, Cindy S. J.: The Mechanics and Dynamics of the UN System for International Drug Control, 14 March 2003.

- Duncan, David F. and Nicholson, Thomas: Dutch drug policy: A model for America? Journal of Health and Social Policy, 1997, 8(3), 1-15.

External links

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA): National report Netherlands, 2006

- EMCDDA ELDD European Legal Map on Possession of cannabis for personal use

- Explanation of the Dutch drugs policy for tourist

- 2000-2001 Progress Report on the Drug Policy of the Netherlands (pdf)

- Article on Amsterdam drug scene

- NL Planet - Dutch Soft Drugs Policy

- "Gedogen" - active Dutch tolerance.

- "The National Institute of the Netherlands in the field of mental health and dependency care (in Dutch)"

- [1]

- "Save the Mushroom" website, mostly in Dutch with some English

Regulation of therapeutic goods Americas Eurasia European Union · India · Netherlands · Norway · Portugal · Singapore · Soviet Union · Switzerland · Thailand · United KingdomOceania Categories:- Dutch society

- Dutch law

- Drug policy by country

- Drugs in the Netherlands

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.