- Curaçao

-

This article is about the island country. For the former colony/territory comprising Curaçao and five other islands, see Curaçao and Dependencies. For the liqueur, see Curaçao (liqueur).

Country of Curaçao Land Curaçao (Dutch)

Pais Kòrsou (Papiamento)

Flag Coat of arms Anthem: Himno di Kòrsou Anthem of Curaçao

Capital

(and largest city)Willemstad

12°7′N 68°56′W / 12.117°N 68.933°WOfficial language(s) Papiamentu 81.2%, Dutch 8% (official) [1] Demonym Curaçaoan Government Constitutional monarchy - Monarch Queen Beatrix - Governor Frits Goedgedrag - Prime Minister Gerrit Schotte Legislature Estates of Curaçao Autonomy within the Kingdom of the Netherlands - Date 10 October 2010 Area - Total 444 km2

171.4 sq miPopulation - 2010 census 142,180 - Density 319/km2 (39th)

821/sq miGDP (PPP) estimate - Total US$ 2,838 million (2008) [2] (177th) - Per capita US$ 20,567 (2009) Currency Netherlands Antillean guilder ( ANG)Time zone -4 (UTC-4) Drives on the right ISO 3166 code CW Internet TLD .an to be discontinued; .cw assigned but not yet activated Calling code +599-9 Curaçao (

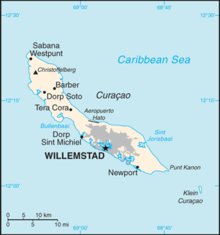

/ˈkʊərəsaʊ/; Dutch: Curaçao, [kyrɑˈsɔu̯];[3] Papiamentu: Kòrsou) is an island in the southern Caribbean Sea, off the Venezuelan coast. The Country of Curaçao (Dutch: Land Curaçao,[4] Papiamentu: Pais Kòrsou[5]), which includes the main island plus the small, uninhabited island of Klein Curaçao ("Little Curaçao"), is a constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. Its capital is Willemstad.

/ˈkʊərəsaʊ/; Dutch: Curaçao, [kyrɑˈsɔu̯];[3] Papiamentu: Kòrsou) is an island in the southern Caribbean Sea, off the Venezuelan coast. The Country of Curaçao (Dutch: Land Curaçao,[4] Papiamentu: Pais Kòrsou[5]), which includes the main island plus the small, uninhabited island of Klein Curaçao ("Little Curaçao"), is a constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. Its capital is Willemstad.Curaçao is the largest and most populous of the three ABC islands (for Aruba, Bonaire, and Curaçao) of the Lesser Antilles, specifically the Leeward Antilles. It has a land area of 444 square kilometres (171 square miles). As of 1 January 2009, it had a population of 141,766.[6]

Prior to 10 October 2010, when the Netherlands Antilles was dissolved, Curaçao was administered as the Island Territory of Curaçao[7] (Dutch: Eilandgebied Curaçao, Papiamentu: Teritorio Insular di Kòrsou), one of five island territories of the former Netherlands Antilles. The ISO 3166-1 alpha-3 country code CUW and the ISO 3166-1 alpha-2 country code CW has been assigned to Curaçao,[8] but the .cw Internet ccTLD is not yet in use.

Contents

Origin of the name

The origin of the name Curaçao is debated. The explanation gathering more consensus among the Portuguese and the Spanish is that the word derives from the Portuguese word for the state of becoming cured (curação). The reason for this is that sailors travelling for months in the sea would often contract scurvy. It appears that in one of such long travels, a group of Portuguese sailors landed for the first time in Curação and were cured from scurvy, probably after eating fruit with vitamin C. The island was known from then on as Ilha da Curação (Island of Healing). Another explanation is that it is derived from the Portuguese word for heart (coração), referring to the island as a centre in trade. Spanish traders took the name over as Curaçao, which was followed by the Dutch. Another explanation is that Curaçao was the name the indigenous peoples of Curaçao had used to label themselves (Joubert and Van Buurt, 1994). This theory is supported by early Spanish accounts, which refer to the indigenous peoples as "Indios Curaçaos" which means "Healing Indians" as the aboriginals were likely already aware of the disease called scurvy and its cure from past experience as in North American natives.

After 1525 the island appeared on Spanish maps as "Curaçote", "Curasaote", and "Curasaore". By the 17th century the island was known on maps as "Curaçao" or "Curazao".

On a map created by Hieronymus Cock in 1562 in Antwerp, the island was referred to as Quracao.[9]

The name "Curaçao" has become associated with a shade of blue, because of the deep-blue version of the liqueur named Curaçao (also known as Blue Curaçao). Today, locally, the island is known as "Dushi Korsou" (Sweet Curaçao).

History

The original inhabitants of Curaçao were Arawak Amerindians. The first Europeans to see the island were members of a Spanish expedition under the leadership of Alonso de Ojeda in 1499. The Spaniards enslaved most of the indigenous population and forcibly relocated the survivors to other colonies where workers were needed. The island was occupied by the Dutch in 1634. The Dutch West India Company founded the capital of Willemstad on the banks of an inlet called the 'Schottegat'. Curaçao had been ignored by colonists because it lacked many things that colonists were interested in, such as gold deposits. However, the natural harbour of Willemstad proved quickly to be an ideal spot for trade. Commerce and shipping — and piracy—became Curaçao's most important economic activities. In addition, the Dutch West India Company made Curaçao a centre for the Atlantic slave trade in 1662. Dutch merchants brought slaves from Africa under a contract with Spain called Asiento. Under this agreement, large numbers of slaves were sold and shipped to various destinations in South America and the Caribbean.

The slave trade made the island affluent, and led to the construction of impressive colonial buildings. Curaçao features architecture that blends Dutch and Spanish colonial styles. The wide range of historic buildings in and around Willemstad earned the capital a place on UNESCO's world heritage list. Landhouses (former plantation estates) and West African style "kas di pal'i maishi" (former slave dwellings) are scattered all over the island and some of them have been restored and can be visited.

In 1795 a major slave revolt took place under the lead of the Negroes Tula Rigaud, Louis Mercier, Bastian Karpata and Pedro Wakao. Up to 4000 Negro slaves on the Northwest section of the island revolted. Over a thousand of the slaves were involved in heavy gunfights and the Dutch feared for their lives. After a month the rebellion was crushed.[10]

Curaçao's proximity to South America translated into a long-standing influence from the nearby Latin American coast. This is reflected in the architectural similarities between the 19th century parts of Willemstad and the nearby Venezuelan city of Coro in Falcón State, the latter also being a UNESCO world heritage site. In the 19th century, Curaçaoans such as Manuel Piar and Luis Brión were prominently engaged in the wars of independence of Venezuela and Colombia. Political refugees from the mainland (like Bolivar himself) regrouped in Curaçao and children from affluent Venezuelan families were educated on the island.

During the 18th and 19th centuries, the island changed hands among the British, the French, and the Dutch several times. Stable Dutch rule returned in 1815, at the end of the Napoleonic wars, when the island was incorporated into the colony of Curaçao and Dependencies. The Dutch abolished slavery in 1863. The end of slavery caused economic hardship, prompting many inhabitants of Curaçao to emigrate to other islands, such as to Cuba to work in sugar cane plantations. Other former slaves had no place to go and remained working for the plantation owner in the so called Paga Tera system. This was an instituted order in which the Negro leases a piece of land and in exchange the Negro must give up most of his harvest to the former slave master. The Negroes were once again forced to work in mass production as in the former days otherwise they would not have enough for themselves after the lord's cut. This lasted till the beginning of the 20th century.

When in 1914 oil was discovered in the Maracaibo Basin town of Mene Grande, the fortunes of the island were dramatically altered. Royal Dutch Shell and the Dutch Government had built an extensive oil refinery installation on the former site of the slave-trade market at Asiento, thereby establishing an abundant source of employment for the local population and fuelling a wave of immigration from surrounding nations. Curaçao was an ideal site for the refinery as it was away from the social and civil unrest of the South American mainland, but near enough to the Maracaibo Basin oil fields. It had an excellent natural harbor that could accommodate large oil tankers. The company brought affluence to the island. Large scale housing was provided and Willemstad developed an extensive infrastructure. However, discrepancies appeared among the social groups of Curaçao. The discontent and the antagonisms between Curaçao social groups culminated in rioting and protest on May 30, 1969. The civil unrest fuelled a social movement that resulted in the local Afro-Caribbean population attaining more influence over the political process (Anderson and Dynes 1975). The island developed a tourist industry and offered low corporate taxes to encourage many companies to set up holdings in order to avoid rigorous schemes elsewhere. In the mid 1980s Royal Dutch Shell sold the refinery for a symbolic amount to a local government consortium. The ageing refinery has been the subject of lawsuits in recent years, which charge that its emissions, including sulfur dioxide and particulate matter, far exceed safety standards.[11] The government consortium currently leases the refinery to the Venezuelan state oil company PDVSA.

In recent years, the island had attempted to capitalize on its peculiar history and heritage to expand its tourism industry. In 1984 the Island Council of Curaçao inaugurated the National Flag and the official anthem of the island. This was done on July 2, which was the date when in 1954 the first elected island council was instituted. Since then, the movement to separate the island from the Antillean federation has steadily become stronger.

Due to an economic slump in recent years, emigration to the Netherlands has been high. Attempts by Dutch politicians to stem this flow of emigration have exacerbated already tense Dutch-Curaçao relations. Immigration from surrounding Caribbean islands, Latin American countries and the Netherlands has taken place.

Geography

Like Aruba and Bonaire, Curaçao is a transcontinental island that is geographically part of South America but is also considered to be part of West Indies and one of the Leeward Antilles. Curaçao and the other ABC Islands are in terms of climate, geology, flora and fauna more akin to nearby Paraguaná Peninsula, Guajira Peninsula, Isla Margarita, Araya and the nearby Venezuelan areas of the Coro region and Falcón State. The flora of Curaçao differs from the typical tropical island vegetation. Xeric scrublands are common, with various forms of cacti, thorny shrubs, evergreens, and the island's national tree, divi-divis. Curaçao's highest point is the 375 km (233 mi) off the coast of Curaçao, to the south-east, lies the small, uninhabited island of Klein Curaçao ("Little Curaçao").

Beaches

Curaçao is known for its coral reefs, used for scuba diving. The beaches on the south side contain many popular diving spots. An unusual feature of Curaçao diving is that the sea floor drops steeply within a few hundred feet of the shore, and the reef can easily be reached without a boat. This drop-off is known as the "blue edge." Strong currents and lack of beaches make the rocky northern coast dangerous for swimming and diving, but experienced divers sometimes dive there from boats when conditions permit. The southern coast is very different and offers remarkably calm waters. The coastline of Curaçao features many bays and inlets, many of them suitable for mooring.

Some of the coral reefs are affected by tourism. Porto Marie Beach is experimenting with artificial coral reefs in order to improve the reef's condition. Hundreds of artificial coral blocks that have been placed are now home to a large array of tropical fish.

The most well-known beaches of Curaçao are:[12]

- Baya Beach

- Blue Bay (Blauwbaai)

- Daaibooi

- Grote Knip (Playa Abou)

- Kleine Knip (Kenepa Chiki)

- Playa Forti

- Playa Gipy

- Playa Jeremi

- Playa Kalki

- Playa Kanoa

- Playa Lagun

- Playa Porto Marie

- Playa Santa Cruz

- Santa Barbara Beach

- Seaquarium Beach

- Westpunt

Climate

Curaçao has a semiarid climate with a dry season from January to September and a wet season from October to December. The temperatures are relatively constant with small differences throughout the year. The trade winds bring cooling during the day and the same trade winds bring warming during the night. The coldest month is January with an average temperature of 26.5 °C (80 °F) and the warmest month is September with an average temperature of 28.9 °C (84 °F). The year's average maximum temperature is 31.2 °C (88 °F). The year's average minimum temperature is 25.3 °C (78 °F). Curaçao lies outside the hurricane belt, but is still occasionally affected by hurricanes, as for example Omar in 2008. A landfall of a hurricane in Curaçao has not occurred since the National Hurricane Center started tracking hurricanes. Curaçao has, however, been directly affected by pre-hurricane tropical storms several times; the latest which did so were Cesar in 1996, Joan-Miriam in 1988, and Tomas in 2010. The latter brushed Curaçao as a tropical storm in early November, dropping up to 265 mm (10.4 in) of precipitation on the territory and triggering widespread flooding.[13] This made Tomas one of the wettest events in the history of Curaçao,[14] as well as one of the most devastating; cumulatively, damage across the island was preliminarily estimated at NAƒ60 million (US$28 million),[15] and 2 fatalities were confirmed.[16]

Climate data for Curaçao Month Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Year Record high °C (°F) 32.8

(91.0)33.2

(91.8)33.0

(91.4)34.7

(94.5)35.8

(96.4)37.5

(99.5)35.0

(95.0)37.4

(99.3)38.3

(100.9)36.0

(96.8)35.6

(96.1)33.3

(91.9)38.3

(100.9)Average high °C (°F) 29.7

(85.5)30.0

(86.0)30.5

(86.9)31.1

(88.0)31.6

(88.9)32.0

(89.6)31.9

(89.4)32.4

(90.3)32.6

(90.7)31.9

(89.4)31.1

(88.0)30.1

(86.2)31.2 Average low °C (°F) 24.3

(75.7)24.4

(75.9)24.8

(76.6)25.5

(77.9)26.3

(79.3)26.4

(79.5)26.1

(79.0)26.3

(79.3)26.5

(79.7)26.2

(79.2)25.6

(78.1)24.8

(76.6)25.6 Record low °C (°F) 20.3

(68.5)20.6

(69.1)21.0

(69.8)22.0

(71.6)21.6

(70.9)22.6

(72.7)22.4

(72.3)21.3

(70.3)21.7

(71.1)21.9

(71.4)22.2

(72.0)21.1

(70.0)20.3

(68.5)Precipitation mm (inches) 44.7

(1.76)25.5

(1.004)14.2

(0.559)19.6

(0.772)19.6

(0.772)19.3

(0.76)40.2

(1.583)41.5

(1.634)48.6

(1.913)83.7

(3.295)96.7

(3.807)99.8

(3.929)553.4

(21.787)Source: [17] Politics

Main article: Politics of CuraçaoCuraçao gained self-government on 1 January 1954 as an island territory of the Netherlands Antilles. Despite this, the islanders did not fully participate in the political process until after the social movements of the late '60s. In the 2000s the political status of the island has been under discussion again, as for the other islands of the Netherlands Antilles, regarding the relationship with the Netherlands and between the islands of the Antilles.

In a referendum held on 8 April 2005, the residents voted for a separate status outside the Netherlands Antilles, like Aruba, rejecting the options for full independence, becoming part of the Netherlands, or retaining the status quo. In 2006, Emily de Jongh-Elhage, a resident of Curaçao, was elected as the new prime minister of the Netherlands Antilles, and not Curaçao.

On 1 July 2007, the island of Curaçao was due to become a country within the Kingdom of the Netherlands. On 28 November 2006, the island council rejected a clarification memorandum on the process. On 9 July 2007 the new island council of Curaçao ratified the agreement previously rejected in November 2006.[18] On 15 December 2008, Curaçao was scheduled to become a separate country within the Kingdom of the Netherlands (like Aruba and the Netherlands Antilles that time). A non-binding referendum on this plan took place in Curaçao on 15 May 2009, in which 52 percent of the voters supported these plans.[19]

Dissolution of the Netherlands Antilles was effected on 10 October 2010.[20] Curaçao is now a country within the Kingdom of the Netherlands, with the Kingdom retaining responsibility for defence and foreign policy. The Kingdom will also oversee the island's finances under a debt-relief arrangement agreed on between the two.[21]

Education

Historically, education on Curaçao, Aruba and Bonaire had been predominantly in Spanish up until the late 19th century. There were also efforts to introduce bilingual popular education in Dutch and Papiamentu in the late 19th century (van Putte 1999). Dutch was made the sole language of instruction in the educational system in the early 20th century to facilitate education for the offspring of expatriate employees of Royal Dutch Shell (Romer, 1999). Papiamentu was tentatively re-introduced in the school curriculum during the mid-1980s. Recent political debate has centered on the issue of Papiamentu becoming the sole language of instruction. Proponents of making Papiamentu the sole language of instruction argue that it will help to preserve the language and will improve the quality of primary and secondary school education. Proponents of Dutch-language instruction argue that students who study in Dutch will be better prepared for the free university education offered to Curaçao residents in the Netherlands.

Public education is based on the Dutch educational system and besides the public schools, private and parochial schools are also available. Since the introduction of a new public education law in 1992, compulsory primary education starts at age six and continues six years, secondary lasts for another five.[22]

The main institute of higher learning is the University of Curaçao, enrolling 2100 students.[22]

Economy

Main article: Economy of CuraçaoAlthough a few plantations were established on the island by the Dutch, the first profitable industry established on Curaçao was salt mining. The mineral was a lucrative export at the time and became one of the major factors responsible for drawing the island into international commerce. Curaçao also became a centre for slave trade during the 17th and 18th centuries.

In the 19th century, phosphate mining also became significant. All the while, Curaçao's fine deep water ports and ideal location in the Caribbean were crucial in making it a significant centre of commerce.

Curaçao has one of the highest standards of living in the Caribbean, with a GDP per capita of US$ 20,500 (2009 est.) and a well-developed infrastructure. The main industries of the island include oil refining, tourism and financial services. Shipping, international trade and other activities related to the port of Willemstad (like the Free Zone) make a contribution to the economy. To achieve the government's aims to make its economy more diverse, significant efforts are being made to attract more foreign investments. This policy is called the 'Open Arms' policy with one of its main features to focus heavily on information technology companies.[23][24][25] For its size, the island has a considerably diverse economy which does not rely mostly on tourism alone as is the case on many other Caribbean islands.

Beginning in January 2014, the Lynx rocketplane is expected to be flying suborbital space tourism flights and scientific research missions from a new spaceport on Curaçao.[26][27]

Curaçao has business ties with the United States, Venezuela and the European Union. It has an Association Agreement with the European Union which allows companies which do business in and via Curaçao to export many products to European markets,[28] free of import duties and quotas. It is also a participant in the US Caribbean Basin Initiative allowing it to have preferential access to the US market.[29]

Prostitution is tolerated. A large open-air brothel called "Le Mirage" or "Campo Alegre" operates near the airport since the 1940s. As prostitution exists in most parts of the world, Curaçao has implemented a different approach on handling prostitution. By monitoring, containing and regulating it, the workers in these establishments are given a safe environment and access to medical practitioners. Despite this, it should be noted that the U.S. State Department stated,"Curaçao, Aruba, and Saint Maarten are destination islands for women trafficked for the sex trade from Peru, Brazil, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, and Haiti, according to local observers."[30] Officials in the government frequently underestimate the extent of human trafficking problems.[30]

Demographics

Ethnicities

Because of its history, the island's population comes from many ethnic backgrounds. There is an Afro-Caribbean majority of mixed African and European descent, and also sizeable minorities of Dutch, Latin American, French, South Asian, East Asian, Portuguese and Levantine people. The Sephardic Jews who arrived from the Netherlands and then-Dutch Brazil since the 17th century have had a significant influence on the culture and economy of the island. The years before and after World War II also saw an influx of Ashkenazi Jews from Eastern Europe, many of whom were Romanian Jews.

In the early 19th century, many Portuguese and Lebanese migrated to Curaçao attracted by the financial possibilities of the island. East and South Asian migrants arrived during the economic boom of the early 20th century. There are also many recent immigrants from neighbouring countries, most notably the Dominican Republic, Haiti, the Anglophone Caribbean and Colombia. In recent years the influx of Dutch pensioners has increased significantly, dubbed locally as pensionados.

Religion

According to the 2001 census, the majority of the inhabitants of Curaçao are Roman Catholic (85%). This includes a shift towards the Charismatic Renewal or Charismatic movement since the mid-seventies. Other major denominations are the Seventh-day Adventist Church and the Methodist Church. Alongside these Christian denominations, some inhabitants practice Montamentu, and other diaspora African religions. Like elsewhere in Latin America, Pentecostalism is on the rise. There are practising Muslims as well as Hindus.

Though small in size, Curaçao's Jewish community has a significant impact on history. Curaçao is home to the oldest active Jewish congregation in the Americas, dating to 1651. The Curaçao synagogue is the oldest synagogue of the Americas in continuous use, since its completion in 1732 on the site of a previous synagogue. The Jewish Community of Curaçao also played a key role in supporting early Jewish congregations in the United States in the 18th and 19th centuries, including in New York City and the Touro Synagogue.

Culture

Curaçao is a polyglot society. The languages widely spoken are Papiamentu, Dutch, English, and Spanish. Most people on the island (85 percent) speak Papiamentu. Many people can speak all four of these languages. Spanish and English both have a long historical presence on the island alongside Dutch and Papiamentu. Spanish remained an important language throughout the 18th and 19th centuries as well due to the close economic ties with nearby Venezuela and Colombia. The use of English dates back to the early 19th century, when Curaçao became a British colony. In fact, after the restoration of Dutch rule in 1815, colonial officers already noted wide use of English among the island (van Putte 1999). Recent immigration from the Anglophone Caribbean and the Netherlands Antillean islands of (St. Eustatius, Saba and Sint Maarten)—where the primary language is English—as well as the ascendancy of English as a world language, has intensified the use of English on Curaçao. For much of colonial history, Dutch was never as widely spoken as English or Spanish and remained exclusively a language for administration and legal matters; popular use of Dutch increased towards the end of the 19th century and the early 20th century (van Putte 1999).

Curaçao is one of just a handful of social language planning instances where creole language became a medium to acquire basic literacy with introduction of Papiamentu as a language of primary school education in 1993.[31]

Literature

Despite the island's relatively small population, the diversity of languages and cultural influences on Curaçao have generated a remarkable literary tradition, primarily in Dutch and Papiamentu. The oral traditions of the Arawak indigenous peoples are lost. West African slaves brought the tales of Anansi, thus forming the basis of Papiamentu literature. The first published work in Papiamentu was a poem by Joseph Sickman Corsen entitled Atardi, published in the La Cruz newspaper in 1905. Throughout Curaçaoan literature, narrative techniques and metaphors best characterized as magic realism tend to predominate. Novelists and poets from Curaçao have made an impressive contribution to Caribbean and Dutch literature. Best known are Cola Debrot, Frank Martinus Arion, Pierre Lauffer, Elis Juliana,Guillermo Rosario, Boeli van Leeuwen and Tip Marugg.

Cuisine

Local food is called Kriyoyo (pronounced the same as criollo, the Spanish word for "Creole") and boasts a blend of flavours and techniques best compared to Caribbean cuisine and Latin American cuisine. Dishes common in Curaçao are found in Aruba and Bonaire as well. Popular dishes include: stobá (a stew made with various ingredients such as papaya, beef or goat), Guiambo (soup made from okra and seafood), kadushi (cactus soup), sopi mondongo (intestine soup), funchi (cornmeal paste similar to fufu, ugali and polenta) and a lot of fish and other seafood. The ubiquitous side dish is fried plantain. Local bread rolls are made according to a Portuguese recipe. All around the island, there are snèk's which serve local dishes as well as alcoholic drinks in a manner akin to the English public house. The ubiquitous breakfast dish is pastechi: fried pastry with fillings of cheese, tuna, ham, or ground meat. Around the holiday season special dishes are consumed, such as the hallaca and pekelé, made out of salt cod. At weddings and other special occasions a variety of kos dushi are served: kokada (coconut sweets), ko'i lechi (condensed milk and sugar sweet) and tentalaria (peanut sweets). The Curaçao liqueur was developed here, when a local experimented with the rinds of the local citrus fruit known as laraha. Surinamese, Chinese, Indonesian, Indian and Dutch culinary influences also abound. The island also has many Chinese restaurants that serve mainly Indonesian dishes such as satay, nasi goreng and lumpia (which are all Indonesian names for the dishes). Dutch specialties such as croquettes and oliebollen are widely served in homes and restaurants.

Sports

Since 2001, the Pabao Little League baseball team from Willemstad, Curaçao has made it all the way to the Little League World Series in Williamsport, Pennsylvania. The team features players from ages 11 and 12 who get a chance to represent the Caribbean region. In 2004 the team from Willemstad, Curaçao won the title game against the United States champion from Thousand Oaks, California. The following year the team from Curaçao made it right back to the championship game but were defeated by Ewa Beach, Hawaii after Michael Memea hit a walk-off home run to win the title game for Hawaii. In 2007 the team lost to Japan in the International Championship game.

In the 2006 World Baseball Classic, Curaçaoans played for the Netherlands team. Shairon Martis, born in Willemstad, provided the highlight of the tournament for the Dutch team by throwing a seven-inning no-hitter against Panama (the game was stopped due to the mercy rule). In addition, Major League player and All Star Andruw Jones and Tirone Maria, currently playing in Aruba, are Curaçaoans.

The prevailing trade winds and warm water make Curaçao a very good location for windsurfing, although the nearby islands of Aruba and Bonaire are far better known in the sport.[32][33] One factor is that the deep water around Curaçao makes it difficult to lay marks for major windsurfing events, thus hindering the island's success as a windsurfing destination. Similarly, the warm clear water around the island makes Curaçao a Mecca for diving.[34]

Notable residents

Famous people from Curaçao include:

In arts and culture

- Kizzy McHugh, a singer songwriter and television personality based in the United States

- Peter Hartman, CEO of KLM

- Ingrid Hoffman, American television personality and restaurateur, chef on Food Network

- Robby Müller, cinematographer, closely associated with Wim Wenders and Jim Jarmusch

- Pernell Saturnino, a graduated percussionist of Berklee College of Music

In politics and government

- Luis Brión, admiral in the Venezuelan War of Independence

- Daniel De Leon, a socialist leader

- Moises Frumencio da Costa Gomez, first Prime Minister of the Netherlands Antilles

- George Maduro, a war hero and namesake of Madurodam in The Hague

- Manuel Carlos Piar, general and competitor of Bolivar during the Venezuelan War of Independence

- Tula, leader of the 1795 slave revolt

In sports

Baseball

Players in Major League Baseball

- Wladimir Balentien, outfielder recently playing for the Cincinnati Reds now in Tokyo Yakult Swallows

- Roger Bernadina, outfielder as of 2011[update] playing for the Washington Nationals

- Kenley Jansen, pitcher currently playing for the Los Angeles Dodgers

- Andruw Jones, outfielder currently playing for the New York Yankees

- Jair Jurrjens, pitcher currently playing for the Atlanta Braves

- Shairon Martis, pitcher, as of 2011[update] playing for the Washington Nationals

- Hensley Meulens, former player and current hitting coach for the San Francisco Giants

- Randall Simon, former first baseman

Football

- Vurnon Anita, a football player in Ajax Amsterdam

- Timothy Cathalina, football player currently playing for Tranmere Rovers F.C.

- Tyrone Maria, footballer who currently plays as a Attacker for SV Bubali in Aruba

Other sports

- Marc De Maar, A professional cyclist who rides for Quickstep

- Shad Gaspard, WWE Pro Wrestler

- Marshall Godschalk, Olympic rower

- Churandy Martina, gold medallist 100m at the Pan American Games 2007

- Jean-Julien Rojer, professional tennis player

See also

- Caribbean Sea

- Curaçao (liqueur)

- Kingdom of the Netherlands

- Leeward Antilles

- Rodents of Curaçao

Notes

- ^ CIA The World Factbook Curaçao

- ^ COUNTRY COMPARISON GDP PURCHASING POWER PARITY, Central Intelligence Agency

- ^ Mangold, Max (2005). "Curaçao". In Dr. Franziska Münzberg. Aussprachewörterbuch. Mannheim: Duden Verlag. ISBN 978-3-411-04066-7. http://www.duden.de. Retrieved 2011-06-16.

- ^ Formal name according to Art. 1 para 1 Constitution of Curaçao (Dutch version)

- ^ Formal name according to Art. 1 para 1 Constitution of Curaçao (Papiamentu version)

- ^ "Statistical Info: Population". Cbs.an. http://www.cbs.an/population/population_b2.asp. Retrieved 2009-05-23.

- ^ English name used by government of Curaçao and Government of Netherlands Antilles (English is official language of Netherlands Antilles and Island Territory of Curaçao)

- ^ "ISO 3166-1 decoding table". International Organization for Standardization. http://www.iso.org/iso/support/country_codes/iso_3166_code_lists/iso-3166-1_decoding_table.htm#CW. Retrieved 2010-12-16.

- ^ Cock's 1562 map at the Library of Congress website

- ^ "Curaçao History". Papiamentu.net. http://www.papiamentu.net/curacao/heroes.html. Retrieved 2010-10-10.

- ^ "Curaçao refinery sputters on, despite emissions". Reuters. 2008-06-30. http://uk.reuters.com/article/oilRpt/idUKN2929170620080701. Retrieved 2008-06-30.

- ^ Curaçao Beaches, New York Times

- ^ (Dutch) "Doden door noodweer op Curaçao". Netherlands National News Agency. November 1, 2010. http://www.nu.nl/buitenland/2369389/doden-noodweer-curaao.html. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ^ (Dutch) Staff Writer (November 2, 2010). "Damdoorbraken in Curaçao door storm Tomas". Nieuws.nl. http://www.myheadlines.org/modules.php?op=modload&name=MyHeadlines&file=index5&sid=1558&cid=3586951&source=Nieuws.nl. Retrieved November 2, 2010.

- ^ (Dutch) Elisa Koek (November 6, 2010). "50 miljoen schade". versgeperst.com. http://www.curalive.com/news/versgeperst/06nov2010-50-miljoen-schade.

- ^ Redactie Aworaki (November 2, 2010). "Twee doden op Curaçao door Tropische Storm Tomas". Aworaki.nl. http://www.rnw.nl/caribiana/article/twee-doden-op-curacao-door-tropische-storm-tomas.

- ^ "Climatological Summary for Curaçao". Meteorological service of Netherlands Antilles and Aruba. May 2011. http://weather.an/climate/cur.climsum.htm.

- ^ The Daily Herald St. Maarten (2007-07-09). "Curaçao IC ratifies November 2 accord". Archived from the original on 11 July 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20070711181904/http://www.thedailyherald.com/news/daily/k045/ratify045.html. Retrieved 2007-07-13.

- ^ "Curaçao referendum approves increasing autonomy". Newser. 2009-05-15. http://www.newser.com/article/d98729g80/curacao-referendum-approves-increasing-autonomy.html. Retrieved 2009-05-23.

- ^ "NOS Nieuws - Antillen opgeheven op 10-10-2010". Nos.nl. 2009-11-18. http://www.nos.nl/nosjournaal/artikelen/2009/10/1/011009_antillen.html. Retrieved 2010-10-10.

- ^ "Status change means Dutch Antilles no longer exists". BBC News. 2010-10-10. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-latin-america-11511355.

- ^ a b South America, Central America and the Caribbean 2003 - Page 593

- ^ "1609_1_DEZ_Manual_binnenw.qxd" (PDF). http://www.curacao-law.com/wp-content/uploads/2006/08/Investors%20Guide%20Curacao%202006.pdf. Retrieved 2010-10-10.

- ^ Mindmagnet.com (2001-03-01). "Ecommerce at Curaçao Corporate". Ecommerceatcuracao.com. http://www.ecommerceatcuracao.com/corporate.htm. Retrieved 2009-05-23.

- ^ "Economic Data Overview". Investcuracao.com. http://www.investcuracao.com/01e01.html. Retrieved 2009-05-23.

- ^ Staff writers (October 6, 2010). "Space Experience Curaçao Announces Wet Lease of XCOR Lynx Suborbital". Space Media Network Promotions. Space-Travel.com. http://www.space-travel.com/reports/Space_Experience_Curaçao_Announces_Wet_Lease_of_XCOR_Lynx_Suborbital_999.html. Retrieved 2010-10-06.

- ^ "Space Experience Curaçao". Home. Space Experience Curaçao. 2009-2010. http://spaceexperiencecuracao.com/. Retrieved 2010-10-06.

- ^ EU Trade Program[dead link]

- ^ "USTR – Caribbean Basin Initiative". Ustr.gov. 2000-10-01. http://www.ustr.gov/Trade_Development/Preference_Programs/CBI/Section_Index.html. Retrieved 2009-05-23.

- ^ a b Trafficking in Persons Report, June 2008, U.S. State Dept. p. 192

- ^ Anthony Liddicoat (15 June 2007). Language planning and policy: issues in language planning and literacy. Multilingual Matters. p. 149. ISBN 978-1-85359-977-4. http://books.google.com/books?id=aP3iylRYWywC&pg=PA149. Retrieved 9 August 2011.

- ^ "Curaçao's Caribbean sister islands, Aruba and Bonaire, are well known in the windsurfing world. Curaçao , which receives the same Caribbean trade winds as its siblings, has remained undiscovered by travelling windsurfers." [1]

- ^ Motion Magazine, June 2005

- ^ New York Times, Frommers Guide to Curaçao water sports. "Scuba divers and snorkellers can expect spectacular scenery in waters with visibility often exceeding 30m (98 ft) at the Curaçao Underwater Marine Park, which stretches along 20 km (12.43 mi) of Curaçao's southern coastline". [2].

References

- Habitantenan di Kòrsou, sinku siglo di pena i gloria: 1499–1999. Römer-Kenepa, NC, Gibbes, FE, Skriwanek, MA., 1999. Curaçao: Fundashon Curaçao 500.

- Social movements, violence, and change: the May Movement in Curaçao. WA Anderson, RR Dynes, 1975. Columbus: Ohio State University Press.

- Stemmen uit het Verleden. Van Buurt, G., Joubert, S., 1994, Curaçao.

- Het Patroon van de Oude Curaçaose Samenleving. Hoetink, H., 1987. Amsterdam: Emmering.

- Dede pikiña ku su bisiña: Papiamentu-Nederlands en de onverwerkt verleden tijd. van Putte, Florimon., 1999. Zutphen: de Walburg Pers

- Halman, Johannes and Robert Rojer (2008). Jan Gerard Palm Music Scores: Waltzes, Mazurkas, Danzas, Tumbas, Polkas, Marches, Fantasies, Serenades, a Galop and Music Composed for Services in the Synagogue and the Lodge. Amsterdam: Broekmans en Van Poppel.*[3]

- Halman, Johannes I.M. and Rojer, Robert A. (2008). Jan Gerard Palm: Life and Work of a Musical Patriarch in Curaçao (In Dutch language). Leiden: KITLV.*[4]

- Palm, Edgar (1978). Muziek en musici van de Nederlandse Antillen. Curaçao: E. Palm. http://books.caribseek.com/Curacao/Muziek_en_Musici_Nederlandse_Antillen.

- Boskaljon, Rudolph (1958). Honderd jaar muziekleven op Curaçao. Anjerpublicaties 3. Assen: Uitg. in samenwerking met het Prins Bernhard fonds Nederlandse Antillen door Van Gorcum. http://books.caribseek.com/Curacao/Honderd_Jaar_Muziekleven_op_Curacao.

External links

- Curaçao-gov.an – official website of the government of Curaçao

- Rinkes Curaçao – Rinkes website about (the architecture of) Curaçao

- Curaçao vacation rentals – Enjoy Curaçao vacation rentals. Bungalows, villas and apartments for rent on Curaçao.

- Curaçao travel guide from Wikitravel

- Curaçao entry at The World Factbook

- Curaçao pictures - photoblog from bRaNdSboRg.CoM

- The Curaçao Island - Information and guide on tourism in Curaçao

Geographic locale  Aruba2 ·

Aruba2 ·  Bonaire (Klein Bonaire) ·

Bonaire (Klein Bonaire) ·  Curaçao (Klein Curaçao) ·

Curaçao (Klein Curaçao) ·  Saba ·

Saba ·  Sint Eustatius ·

Sint Eustatius ·  Sint Maarten

Sint Maarten

1The Netherlands Antilles was dissolved on 10 October 2010

2Aruba seceded from the Netherlands Antilles on 1 January 1986

Countries and territories of the Caribbean Sovereign states Other republicsDependencies and other areas by parent state United KingdomNetherlandsAruba · Bonaire · Curaçao · Saba · Sint Eustatius · Sint MaartenFranceUnited StatesCountries and dependencies of North America Sovereign states - Antigua and Barbuda

- Bahamas

- Barbados

- Belize

- Canada

- Costa Rica

- Cuba

- Dominica

- Dominican Republic

- El Salvador

- France (Guadeloupe · Martinique)

- Grenada

- Guatemala

- Haiti

- Honduras

- Jamaica

- Mexico

- Nicaragua

- Netherlands (Bonaire · Saba · Sint Eustatius)

- Panama

- St. Kitts and Nevis

- Saint Lucia

- St. Vincent and the Grenadines

- Trinidad and Tobago

- United States

Dependencies DenmarkFranceNetherlands- Aruba

- Curaçao

- Sint Maarten

United KingdomUnited StatesInternational membership and history Nations MembersAntigua and Barbuda · Bahamas1 · Barbados · Belize · Dominica · Grenada · Guyana · Haiti1 · Jamaica · Montserrat2 · St. Kitts and Nevis · St. Lucia · St. Vincent and the Grenadines · Suriname · Trinidad and TobagoAssociate membersObservers

Institutions Related organizations 1 Member of the Community but not of the CARICOM Single Market and Economy (CSME). 2 British overseas territory awaiting entrustment to join the CSME.Outlying territories of European countries Territories under European sovereignty but closer to or on continents other than Europe (see inclusion criteria for further information)Denmark France Italy Netherlands Norway Portugal Spain United

KingdomAnguilla · Bermuda · British Virgin Islands · Cayman Islands · Falkland Islands · Montserrat · Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha · Turks and Caicos Islands · British Antarctic Territory · British Indian Ocean Territory · Pitcairn Islands · South Georgia and the South Sandwich IslandsDutch Empire Colonies and trading posts of the Dutch East India Company (1602-1798) GovernoratesAmbon · Banda · Batavia · Cape Colony · Ceylon · Coromandel · Formosa · Northeast coast of Java · Makassar · Malacca · MoluccasDirectoratesCommandmentsResidenciesColonies and trading posts of the Dutch West India Company (1621-1792) Colonies in the AmericasAcadia · Berbice† · Cayenne · Curaçao and Dependencies · Demerara · Essequibo · Brazil · New Netherland · Pomeroon · Sint Eustatius and Dependencies · Suriname‡ · Tobago · Virgin IslandsTrading posts in Africa† Governed by the Society of Berbice · ‡ Governed by the Society of SurinameSettlements of the Noordsche Compagnie (1614-1642) SettlementsColonies of the Kingdom of the Netherlands (1815-1962) Until 1825Until 1853Until 1872Until 1945Until 1954Until 1962† Became constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Netherlands; Suriname gained full independence in 1975, Curaçao and Dependencies was renamed to the Netherlands Antilles, which was eventually dissolved in 2010.Kingdom of the Netherlands (1954-Present) Constituent countriesDependencies of European Union states

Denmark France United Kingdom Anguilla · Bermuda · British Antarctic Territory · British Indian Ocean Territory · British Virgin Islands · Cayman Islands · Falkland Islands · Gibraltar · Montserrat · Pitcairn Islands · Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha · South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands · Turks and Caicos IslandsCategories:- Curaçao

- Dutch-speaking countries

- Kingdom of the Netherlands

- Islands of the Netherlands Antilles

- States and territories established in 2010

- Caribbean countries

- Dependent territories in North America

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.