- Saint Pierre and Miquelon

-

Saint Pierre and Miquelon

Flag Coat of arms Motto: A Mare Labor

English: "From the Sea, Work"Capital

(and largest city)Saint-Pierre

46°47′N 56°10′W / 46.783°N 56.167°WOfficial language(s) French Government Overseas collectivity - President of France Nicolas Sarkozy - Prefect Jean-Régis Borius - President of the Territorial Council Stéphane Artano Overseas collectivity of France - Ceded by the UK 30 May 1814 - Overseas territory 27 October 1946 - Overseas department 17 July 1976 - Territorial collectivity 11 June 1985 - Overseas collectivity 28 March 2003 Area - Total 242 km2 (208th)

93 sq mi- Water (%) negligible Population - 2011 estimate 5,888[1] (227th) - 2009 census 6,345[2] - Density 24.3/km2 (188th)

62.9/sq miGDP (PPP) 2004 estimate - Total €161.131 million[3] - Per capita €26,073[3] Currency Euro (€) ( EUR)Time zone (UTC−3) - Summer (DST) (UTC−2) observes North American DST rules ISO 3166 code PM Internet TLD .pm Calling code +508 Saint Pierre and Miquelon (French: Collectivité territoriale de Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon, French pronunciation: [sɛ̃ pjɛʁ e mikˈlɔ̃]) is a self-governing territorial overseas collectivity of France.[1] It is the only remnant of the former colonial empire of New France that remains under French control.[4]

The islands are situated at the entrance of Fortune Bay, which extends into the southern coast of Newfoundland, near the Grand Banks.[5] They are 6,470 kilometres from Brest, the nearest point in Metropolitan France,[5] but just 20 kilometres off the Burin Peninsula of Newfoundland.[6]

Contents

Etymology

Saint-Pierre is French for Saint Peter, who is a patron saint of fishermen.[7]

The present name of Miquelon was first noted in the form of "Micquelle" in the Basque sailor Martin de Hoyarçabal's navigational pilot for Newfoundland.[8] It has been claimed that the name "Miquelon" is a Basque form of Michael,[9][10][11] but it appears that this is not a usual form in that language. Many Basques speak Spanish as well as Basque, and Miquelon may have been influenced by the Spanish name Miguelón, a form of Miguel meaning "big Michael".

The adjoining island's name of "Langlade" is a corruption of "l'île à l'Anglais" (Englishman's Island).[10]

History

The islands of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon were discovered by Europeans on October 21, 1520, by the Portuguese João Álvares Fagundes, who bestowed on them their original name of "Islands of the 11,000 Virgins", as the day marked the feast day of St. Ursula and her virgin companions.[12] They were made a French possession in 1536 by Jacques Cartier on behalf of the King of France.[13] Though already frequented by Micmac Indians[14] and Basque and Breton fishermen,[13] the islands were not permanently settled until the end of the 17th century: four permanent inhabitants were counted in 1670, and 22 in 1691.[13]

In 1670, during Jean Talon’s tenure as Intendant of New France,[15] a French officer annexed the islands when he found a dozen French fishermen camped there. English ships soon began to harass the French, pillaging their camps and ships.[14] By the early 1700s, the islands were again uninhabited, and were ceded to the English by the Treaty of Utrecht which ended the War of the Spanish Succession in 1713.[14]

French fishermen occasionally still visited the region, although they preferred the French Shore of Newfoundland, richer in fish and with greater possibilities for provisioning and repairs compared to these smaller islands.[14] Under the terms of the 1763 Treaty of Paris which put an end to the Seven Years' War, France ceded all its north American possessions, keeping only Saint-Pierre and Miquelon, as well as fishing rights on the coasts of Newfoundland.[16] After the long interlude of British occupation from 1714 to 1763, the islands knew little peace, but witnessed a significant rise in business and population, as they were now the last French territory in North America.[13]

Britain invaded and razed the colony in 1778, during the American revolutionary war, and the entire population of 2,000 was sent back to France.[15] By the 1780s, about 1,000 or 1,500 people lived on the islands, their numbers doubling during the fishing season. The French Revolutionary Wars affected the archipelago dramatically: in 1793, the British landed in Saint-Pierre and, the following year, expelled the French population, and tried to install British settlers.[14] The British colony was in turn sacked by French troops in 1796. The Treaty of Amiens of 1802 returned the islands to France, but Britain reoccupied them when hostilities recommenced the next year.[14]

The 1814 Treaty of Paris gave them back to France, though Britain occupied them yet again during the Hundred Days War. France then reclaimed uninhabited islands in which all structures and buildings had been destroyed or fallen into disrepair.[14] The islands were resettled in 1816. The settlers were mostly Basques, Bretons and Normans, who were joined by various other elements, particularly from the nearby island of Newfoundland.[13] Only around the middle of the century did increased fishing bring a certain prosperity to the little colony.[14]

Modern history

During the early 1910s the colony suffered severely as a result of unprofitable fisheries, and large numbers of its people emigrated to Nova Scotia and Quebec.[17] The draft imposed on all male inhabitants of conscript age after the beginning of World War I crippled the fisheries, which could not be prosecuted by the older people and the women and children.[17] About 400 men from the colony served in the French military during World War I, 25% of whom died.[18] The increase in the adoption of the steam trawlers in the fisheries also contributed to reduce the employment opportunities.[17]

Smuggling had always been an important economic activity in the islands, but it became especially prominent in the 1920s with the institution of prohibition in the United States.[18] In 1931, the archipelago was reported to have imported 1,815,271 US gallons (6,871,550 litres) of whisky from Canada in 12 months, most of it to be smuggled into the United States.[19] The end of prohibition in 1933 plunged the islands into economic depression.[20]

After the fall of France, most of the war veterans and sailors in the colony supported de Gaulle. The administrator of the colony, Gilbert de Bournat, sided with Vichy.[18] De Gaulle decided to seize the archipelago, over the opposition of the United States. The general covertly gave Admiral Émile Muselier the order to proceed, resulting in the successful Free French coup de main on Christmas Day 1941.[21] The State Department and Cordell Hull in particular were infuriated by the result. The incident ultimately served to focus the American public opinion on the ambivalence of the Roosevelt administration in its dealings with Vichy,[21] and also led to a lasting distrust between De Gaulle and Roosevelt.[22]

In a quick plebiscite the next day, the population endorsed the takeover,[21] and the resounding vote in favour of Free France led Muselier to appoint Lieutenant Alain Savary as governor.[15] After the approval of the 1958 French constitutional referendum, the islands were given the options of becoming fully integrated with France, becoming self-governing states within the French Community or preserving the status of overseas territory; they decided to remain a territory.[23]

Politics

Since March 2003, Saint Pierre and Miquelon has been an overseas collectivity with a special statute. The archipelago became an overseas territory in 1946, then an overseas department in 1976, before acquiring the status of territorial collectivity in 1985.[24] The archipelago has two communes, Saint Pierre and Miquelon-Langlade.[25] A third commune, Isle-aux-Marins, existed until 1945, when it was absorbed by the municipality of Saint-Pierre.[13] The inhabitants possess French citizenship and suffrage.[26] Saint Pierre and Miquelon send a senator and a deputy to the National Assembly in Paris, and enjoy an amount of autonomy concerning taxes, customs and excise.[15]

The Prefect of Saint Pierre and Miquelon is appointed by France and represents the Paris government in the territory.[20] He is in charge of national interests, law enforcement, public order and, under the conditions set by the statute of 1985, administrative control.[27] The current prefect is Jean-Régis Borius.[28] The local legislative body, the Territorial Council (French: Conseil Territorial), has 19 members: four councillors from Miquelon-Langlade and 15 from Saint-Pierre.[25] The President of the Territorial Council is the head of a delegation of "France in the name of Saint Pierre and Miquelon" for international events like the annual meetings of NAFO and ICCAT.[25]

France is responsible for the defence of the islands.[1] The Maritime Gendarmerie has maintained a patrol boat, the Law enforcement in Saint Pierre and Miquelon is the responsibility of a branch of the French Gendarmerie Nationale. There are two police stations in the archipelago.[31]

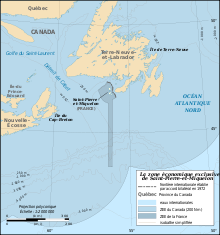

Maritime boundary case

Main article: Canada–France Maritime Boundary CaseFrance claimed a 200-mile exclusive economic zone for Saint-Pierre and Miquelon, and in August 1983 the gunboat Le Henaff and a seismic ship Lucien Beaufort were sent to explore for oil in the disputed zone.[32] In addition to the potential oil reserves, cod fishing rights in the Grand Banks were at stake in the dispute. In the late 1980s, indications of declining fish stocks began to raise serious concern over the depletion of the fishery.[32] In 1992, an arbitration panel awarded the islands an exclusive economic zone of 12,348 sq km to settle a longstanding territorial dispute with Canada, although it represents only 25% of what France had sought.[1]

The 1992 decision fixed the maritime boundaries between Canada and the islands, but did not demarcate the continental shelf.[33]

Geography

Located in the heart of the Grand Banks in the North Atlantic, 25 km southwest of Newfoundland, the archipelago of Saint Pierre and Miquelon is composed of eight islands, totalling 242 km², of which only two are inhabited.[34] The islands are bare and rocky, with steep coasts, and only a thin layer of peat to soften the hard landscape.[6]

Saint Pierre Island, whose area is smaller (26 km²), is the most populous and the commercial and administrative center of the archipelago. A new airport has been in operation since 1999 and is capable of accommodating long-haul flights from metropolitan France.[24]

Miquelon-Langlade, the largest island, is in fact composed of two islands, Miquelon (110 km²) connected to Langlade (91 km²) by the Dune de Langlade, a 10 km-long sandy isthmus.[24] A storm would have severed it in the 18th century, separating the two islands for several decades, before the currents reconstructed the isthmus.[13] The waters between Langlade and Saint-Pierre were called "the Mouth of Hell" (French: Gueule d'Enfer) until about 1900, as more than 600 shipwrecks have been recorded in that point since 1800.[35] North of Miquelon Island is the village (710 inhabitants), while Langlade Island was almost deserted (only one inhabitant in the 1999 census).[13]

A third, formerly inhabited island, Isle-aux-Marins, known as Île-aux-Chiens until 1931 and located a short distance from the port of Saint-Pierre, has been uninhabited since 1963.[13]

Environment

Seabirds are the most common fauna.[26] Seals and other wildlife can be found in the Grand Barachois Lagoon of Miquelon. Every spring, whales migrating to Greenland are visible off the coasts of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon. Trilobite fossils have been found on Langlade. There were a number of stone pillars off the island coasts called "L'anse aux Soldats" that have eroded away and disappeared in the 1970s.[36] The rocky islands are barren, except for scrubby yews and junipers and thin volcanic soil.[35] The forest cover of the hills, except in parts of Langlade, had been removed for fuel long ago.[26]

Climate

The archipelago is characterized by a cold oceanic climate, under the influence of polar air masses and the cold Labrador Current.[34] The winters are less severe than in Canada: the average temperature is +5.3°C, with a temperature range of 19°C between the warmest (15.7°C in August) and coldest months (- 3.6°C in February).[34] Precipitation is abundant (1,312 mm per year) and regular (146 days per year), falling as snow and rain.[34] Because of its location at the confluence of the cold waters of the Labrador Current and the warm waters of the Gulf Stream, the archipelago is also crossed a hundred days a year by fog banks, mainly in June and July.[34] Two other climatic elements are crucial: the extremely variable winds and haze during the spring to early summer.[2]

Economy

The inhabitants have traditionally earned their livelihood by fishing and by servicing fishing fleets operating off the coast of Newfoundland.[1] The climate and the small amount of available land hardly favour activity such as farming and livestock (weather conditions are severe, the soil is peaty, clayey and largely infertile), which confines the growing season to a few weeks.[37] Since 1992, the economy has been in steep decline, following the depletion of fish stocks, the limitation of fishing areas and the ban imposed on all cod fishing by the Canadian Government.[38]

The rise in unemployment has been curtailed by the state financial aid for the retraining of businesses and individuals. The construction of the second airport runway has also helped sustain the activity in the construction industry and public works.[24] Fish farming, crab fishing, and agriculture are being developed to diversify the local economy.[1] The future of Saint Pierre and Miquelon rests on tourism, fisheries and aquaculture. Explorations are underway to exploit deposits of oil and gas.[24] Tourism relies on the proximity to Canada, while commerce and crafts make up the bulk of the business sector.[37]

The labour market is characterized by high seasonality, due to climatic hazards. Traditionally, all outdoor activities (construction, agriculture, etc.) were suspended between December and April.[39] In 1999, the unemployment rate was 12.8%, and a third of the employed worked in the public sector. The employment situation was worsened by the complete cessation of deep sea fishing, the traditional occupation of the islanders, as the unemployment rate in 1990 was lower at 9.5%.[13] The unemployment for 2010 shows a decrease from 2009, from 7.7% to 7.1%.[39] Exports are very low (5.1% of GDP) while imports are significant (49.1% of GDP).[40] About 70% of the islands’ supplies are imported from Canada or from France via Nova Scotia.[26]

The local currency is the euro, but Canadian dollars are also widely accepted and also used as a local currency.[41] The "Institut d'émission des départements d'outre-mer" (IEDOM), the French public institution responsible for issuing currency in the overseas territories that use the euro on behalf of the Bank of France, has had an agency in Saint Pierre since 1978.[42] The islands have issued their own stamps from 1885 to the present, except for a period between 1 April 1978 and 3 February 1986 when French stamps were used.[43]

Demographics

Historical populations Year Pop. ±% 1847 1,665 — 1860 2,916 +75.1% 1870 4,750 +62.9% 1897 6,352 +33.7% 1902 6,842 +7.7% 1911 4,209 −38.5% 1921 3,918 −6.9% 1931 4,321 +10.3% 1945 4,354 +0.8% 1957 4,879 +12.1% 1967 5,235 +7.3% 1974 5,840 +11.6% 1982 6,041 +3.4% 1990 6,277 +3.9% 1999 6,316 +0.6% 2009 6,345 +0.5% INSEE (1847-1962;[44] 1967-1999;[45] 2009)[2] The total population of the islands in January 2009 was 6,345, of which 5,707 lived in Saint-Pierre and 638 in Miquelon.[2] As of the 1999 census, 76% of the population was born on the archipelago, while 16.1% were born in metropolitan France, a remarkable increase from the 10.2% in 1990. In the same census, less than 1% of the population reported being a foreign national.[13] The archipelago has a high emigration rate, especially among young adults, who often leave for their studies without returning afterwards.[13] Even at the time of the great prosperity of the cod fishery, the population growth had always been constrained by the geographic remoteness, harsh climate and infertile soils.[13]

Ethnography

While some ruins show a presence of Amerindians on the archipelago, it is unlikely that there were real settlements beyond occasional fishing and hunting expeditions.[2] The current population is the result of inflows of settlers from the French ports, mostly Normans, Basques, Breton and Saintongeais, and also from Acadia and Newfoundland.[2]

Languages and religion

The inhabitants speak French, their customs and traditions are similar to the ones found in metropolitan France.[26] The French spoken on the archipelago is closer to metropolitan French than to Quebecois French, while maintaining a number of unique features.[46] Basque, formerly spoken in private settings by people of Basque ancestry, disappeared from the island by the late 1950s.[47]

The majority of the population is Roman Catholic,[26] and the islands are home to the Roman Catholic Vicariate Apostolic of Iles Saint-Pierre and Miquelon.

Culture

Every year in the summer there is a Basque Festival, with demonstrations of harrijasotzaile (stone heaving), haitzkolari (lumberjack skills), and pelota.[48] The local cuisine is mostly based on seafood such as lobster, snow crab, cod, mussels and many cod-based dishes.[49]

Ice hockey is very popular in Saint-Pierre and Miquelon. Several players from the islands have played on French teams and even participated on the French national ice hockey team in the Olympics.

Street names are not commonly used on the islands. Directions and locations are commonly given using nicknames and the names of nearby residents.[50]

The only time the guillotine was ever used in North America was in Saint-Pierre in the late 19th century. Joseph Néel was convicted of killing Mr. Coupard on Île aux Chiens on 30 December 1888, and executed by guillotine on 24 August 1889. The guillotine had to be shipped from Martinique and it did not arrive in working order. It was very difficult to get anyone to perform the execution; finally a recent immigrant was coaxed into doing the job. This event was the inspiration for the film The Widow of Saint-Pierre (La Veuve de Saint-Pierre) released in 2000. The guillotine is now in a museum in Saint-Pierre.

Transportation

Main article: Transport in Saint Pierre and MiquelonFor many years, no direct air link has connected the islands and mainland France.[24] The new airport of Saint-Pierre, opened in 1999, was intended to overcome this lack, but the situation remained unchanged as of 2007.[24] Flights from and to Saint-Pierre all pass through Canada.[24] Air Saint-Pierre’s ATR 42 aircraft flies from the Canadian airports of St John's, Sydney, Halifax and Montreal all year round.[51]

The islands are connected with the town of Fortune, Newfoundland, by two ferries which provide regular service all year.[51] The ferries do not carry vehicles.[51]

Communications

Main article: Telecommunications in Saint-Pierre and MiquelonSaint-Pierre and Miquelon has four radio stations, all of them on the FM band (the last stations converted from AM band in 2004). Three of the stations are on Saint-Pierre, two of which are owned by Réseau France Outre-mer, along with one RFO station on Miquelon. At night, these stations broadcast France-Inter. The other station (Radio Atlantique) is an affiliate of Radio France Internationale. The nation is linked to North America and Europe by satellite communications for telephone and television service.

The department of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon is served by three television stations: Télé Saint-Pierre et Miquelon (call letters FQN) on Channel 8, with a repeater on Channel 31, and Tempo on Channel 6. While Saint-Pierre and Miquelon use the French SECAM-K1 standard for television broadcasts, the local telecommunications provider (SPM Telecom) carries many North American television stations and cable channels, converted from North America's NTSC standard. In addition, Télé Saint-Pierre et Miquelon is carried on Shaw Direct satellite and most digital cable services in Canada, converted to NTSC.

SPM Telecom also is the department's main Internet Service Provider, with its internet service being named "Cheznoo" (a play on Chez-Nous, French for "Our Place"). SPM Telecom also offers cellular phone and mobile phone service (for phones that adhere to the GSM standard). SPM Telecom uses the GSM 900 MHz band,[52] which is different from the GSM 850 MHz and 1900 MHz bands used in the rest of North America.

The islands are a separate country among radio amateurs. They also have a separate ITU prefix, FP. Therefore Saint-Pierre and Miquelon are visited by radio amateurs every year, mainly from the US, who activate the islands on amateur radio frequencies. These activities have made the islands well known among radio amateurs all over the world as the geographic location of Saint Pierre and Miquelon gives a very good takeoff for shortwave communication all over the world.

Education and healthcare

The archipelago has no institutions of higher education (beyond the undergraduate level), therefore students who wish to further their studies are granted access to the scholarships to study overseas. Most students go to France, but others study in Canada, mainly in New Brunswick.[53]

Saint-Pierre and Miquelon's health care system is almost entirely public and free.[53] In 1994, France and Canada signed an agreement allowing the residents of the archipelago to be treated in St. John's, Newfoundland.[53] Hôpital François Dunan provides basic care and emergency care for residents of both islands.[54]

Time zone

The UTC-3 timezone is used in Saint-Pierre and Miquelon. Also, daylight saving time is observed according to the North American schedule, instead of the European schedule used in metropolitan France.

The following tables compare the time of day for various locales with Saint-Pierre and Miquelon:[55]

Locale Time of Day Common Time Zone Name Coordinated Universal Time Paris, France 07:33, November 22, 2011 (CET / CEST) Central European Time (CET) UTC+1 London, UK 06:33, November 22, 2011 (GMT / BST) Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) UTC Nuuk, Greenland 03:33, November 22, 2011 (WGT) Western Greenland Time (WGT) UTC-3 Saint-Pierre and Miquelon 03:33, November 22, 2011 (PMST) Saint-Pierre & Miquelon Standard Time (PMST) UTC-3 St. John's, NL, Canada 03:03, November 22, 2011 (NST) Newfoundland Standard Time (NST) UTC-3:30 Halifax, NS, Canada 02:33, November 22, 2011 (AST) Atlantic Standard Time (AST) UTC-4 New York, NY, USA 01:33, November 22, 2011 (EST) Eastern Standard Time (EST) UTC-5 See also

- Outline of Saint Pierre and Miquelon

- Index of Saint Pierre and Miquelon-related articles

- Overseas departments and territories of France

References

- ^ a b c d e f Saint Pierre and Miquelon entry at The World Factbook

- ^ a b c d e f Présentation - L'Outre-Mer

- ^ a b Evaluation du PIB 2004 de Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon - janvier 2007, page 24

- ^ St. Pierre & Miquelon at Google Books By USA International Business Publications

- ^ a b Les iles Saint-Pierre et Miquelon — Notes de la conférence donnée à l'Institut Canadien, devant la Société Géographique de Québec, le 29 avril 1880, par Son Excellence le comte de Premio-Real, consul-général d'Espagne.

- ^ a b St. Pierre et Miquelon: Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage

- ^ "PATRON SAINT INDEX TOPIC: fishermen, anglers". Catholic Community Forum. Archived from the original on 20 February 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20070220040300/http://www.catholic-forum.com/Saints/pst00290.htm.

- ^ Hoyarçabal, Martin de: Les voyages aventureux du Capitaine Martin de Hoyarsal, habitant du çubiburu (Bordeaux, France, 1579)

- ^ The Basques of Saint Pierre and Miquelon, Buber's Basque Page dated 30 April 2006 (accessed 27 September 2007).

- ^ a b Saint-Pierre & Miquelon Tourism Agencies in Saint Pierre et Miquelon, Miquelon Consulting, 2006 (accessed 27 September 2007)

- ^ Cormier, Marc Albert: Toponymie ancienne et origine des noms Saint-Pierre, Miquelon et Langlade. The Northern Mariner Vol. 7, Ottawa, 1997. pp 1:29-44

- ^ Placenames of the world: origins and meanings of the names for 6,600 ... at Google Books By Adrian Room

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Le recensement de la population à Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon — INSEE, August 2000

- ^ a b c d e f g h France's Overseas Frontier: Départements Et Territoires D'outre-mer at Google Books By Robert Aldrich, John Connell

- ^ a b c d The French Atlantic: travels in culture and history at Google Books By Bill Marshall

- ^ Atlantic Canada at Google Books By Benoit Prieur

- ^ a b c

Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). "St Pierre". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. http://www.1911encyclopedia.org/St_Pierre.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). "St Pierre". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. http://www.1911encyclopedia.org/St_Pierre. - ^ a b c The Fog of War: Censorship of Canada's Media in World War II at Google Books By Mark Bourrie

- ^ Special Correspondence, THE NEW YORK TIMES, October 25, 1931, Section Week End Cables, Page E6

- ^ a b BBC News - Regions and territories: St Pierre and Miquelon

- ^ a b c War, cooperation, and conflict: the European possessions in the Caribbean ... at Google Books By Fitzroy André Baptiste

- ^ Churchill, Winston S. (1950). The Second World War. 3: The Grand Alliance. p. 666.

- ^ The Calgary Herald - Google News Archive Search

- ^ a b c d e f g h Insee - Population - Le recensement de la population à Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon en 2006

- ^ a b c SODEPAR - Saint-Pierre et Miquelon, Statut spécifique

- ^ a b c d e f Saint-Pierre and Miquelon at Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Portail internet des services de l'Etat: La préfecture

- ^ Portail internet des services de l'Etat: M. Jean-Régis BORIUS - Préfet de Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon

- ^ Berly, Michel; Bastien, Jean-Marie. "Historique: Site non officiel de la gendarmerie nationale" (in French). http://www.cheznoo.net/spmgend/historique.htm. Retrieved 2010-08-07.

- ^ "Ocean Guardian II: September 13–14, 2005; Evaluation Report" (PDF). Canadian Coast Guard. http://www.ccg-gcc.gc.ca/folios/00027/docs/2005018_eval_report-eng.pdf. Retrieved 2010-08-07.

- ^ Portail internet des services de l'Etat: La Gendarmerie Nationale

- ^ a b Canadian foreign policy: defining the national interest at Google Books By Steven Kendall Holloway

- ^ St Pierre and Miquelon — Squaring off for a seabed scrap — The Economist

- ^ a b c d e Rapport annuel 2010 IEDOM Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon, page 16

- ^ a b Saint-Pierre and Miquelon - The Canadian Encyclopedia

- ^ "La Géologie des îles Saint-Pierre et Miquelon" (in French). Encyclopédie des îles Saint-Pierre & Miquelon. Miquelon Conseil. Archived from the original on 11 January 2006. http://web.archive.org/web/20060111105117/http://www.grandcolombier.com/2003-geographie/geologie/index.html.

- ^ a b Economie - L'Outre-Mer

- ^ French islands bid for oil-rich sea — BBC News

- ^ a b Rapport annuel 2010 IEDOM Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon, page 29

- ^ Evaluation du PIB 2004 de Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon - janvier 2007, page 32

- ^ The rough guide to Canada at Google Books By Tim Jepson, Phil Lee, Tania Smith, Emma Rose Rees, Christian Williams

- ^ Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon - IEDOM

- ^ "ST. PIERRE ET MIQUELON". Online Catalogue. Stanley Gibbons. http://www.stanleygibbons.com/mc/search_results.asp?page=results&subcountry=769&pRow=999&xFilter=0&country=573. Retrieved 1 December 2007.

- ^ Demographie - Population totale au recensement : Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon (serie historique 1847-1962) - série arrêtée

- ^ Demographie - Population totale au recensement : Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon - série arrêtée

- ^ 1969 – Le français parlé aux îles Saint-Pierre et Miquelon (E. Aubert de la Rüe) Le GrandColombier.com

- ^ RadioBarachois » The Basque colony of Saint-Pierre et Miquelon.

- ^ "'Zazpiak Bat' Basque Club" (in French). http://www.cheznoo.net/zazpiak-bat/. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ 2011, Année des Outre-mer - Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon

- ^ Emile SASCO. "Historique des Rues de Saint-Pierre" (in French). Encyclopédie des îles Saint-Pierre & Miquelon. Miquelon Conseil. http://www.grandcolombier.com/histoire/1918-1939-lentre-deux-guerres/historique-des-rues-de-saint-pierre/.

- ^ a b c Tourism in Saint-Pierre and Miquelon islands - How to get here

- ^ "GSM Coverage Maps - Saint-Pierre and Miquelon". http://www.gsmworld.com/roaming/gsminfo/cou_pm.shtml. Retrieved 2010-07-04.

- ^ a b c Saint-Pierre and Miquelon Community Profile - Overview

- ^ "Portail internet des services de l'Etat: Le Centre Hospitalier François Dunan" (in French). http://www.saint-pierre-et-miquelon.pref.gouv.fr/sections/services_de_letat/les_etablissements_p/le_centre_hospitalie/. Retrieved 2010-07-04.

- ^ Date and Time.com. "Saint-Pierre, Saint Pierre and Miquelon". http://www.timeanddate.com/worldclock/timezone.html?n=730. Retrieved 2009-11-30.

External links

- Saint Pierre and Miquelon at the Open Directory Project

- Government of Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon (French)

- Comité Régional du Tourisme

- Saint-Pierre and Miquelon travel guide from Wikitravel

- History of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon

Coordinates: 46°47′N 56°12′W / 46.783°N 56.2°W

Overseas departments and territories of France

Overseas departments and territories of FranceInhabited areas  Special status

Special statusUninhabited areas Pacific Ocean French Southern and

Antarctic LandsBanc du Geyser4 · Bassas da India4 · Europa Island4 · Glorioso Islands3, 4, 5 · Juan de Nova Island4 · Tromelin Island4, 51 Also known as overseas regions. 2 Claimed by Comoros. 3 Claimed by Madagascar. 4 Claimed by Seychelles. 5 Claimed by Mauritius.Countries and dependencies of North America Sovereign states - Antigua and Barbuda

- Bahamas

- Barbados

- Belize

- Canada

- Costa Rica

- Cuba

- Dominica

- Dominican Republic

- El Salvador

- France (Guadeloupe · Martinique)

- Grenada

- Guatemala

- Haiti

- Honduras

- Jamaica

- Mexico

- Nicaragua

- Netherlands (Bonaire · Saba · Sint Eustatius)

- Panama

- St. Kitts and Nevis

- Saint Lucia

- St. Vincent and the Grenadines

- Trinidad and Tobago

- United States

Dependencies DenmarkFrance- Clipperton Island

- St. Barthélemy

- St. Martin

- St. Pierre and Miquelon

NetherlandsUnited KingdomUnited StatesOutlying territories of European countries Territories under European sovereignty but closer to or on continents other than Europe (see inclusion criteria for further information)Denmark France Clipperton Island · French Guiana · French Polynesia · Guadeloupe · Martinique · Mayotte · New Caledonia · Réunion · Saint Barthélemy · Saint Martin · Saint Pierre and Miquelon · Wallis and FutunaItaly Netherlands Norway Portugal Spain United

KingdomAnguilla · Bermuda · British Virgin Islands · Cayman Islands · Falkland Islands · Montserrat · Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha · Turks and Caicos Islands · British Antarctic Territory · British Indian Ocean Territory · Pitcairn Islands · South Georgia and the South Sandwich IslandsMember states and observers of the Francophonie Members - Albania

- Andorra

- Armenia

- Belgium

- Benin

- Bulgaria

- Burkina Faso

- Burundi

- Cambodia

- Cameroon

- Canada

- Cape Verde

- Central African Republic

- Chad

- Comoros

- Cyprus1

- Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Republic of the Congo

- Côte d'Ivoire

- Djibouti

- Dominica

- Egypt

- Equatorial Guinea

- France

- (French Guiana

- Guadeloupe

- Martinique

- St. Pierre and Miquelon

- Gabon

- Ghana1

- Greece

- Guinea

- Guinea-Bissau

- Haiti

- Laos

- Luxembourg

- Lebanon

- Macedonia2

- Madagascar

- Mali

- Mauritania

- Mauritius

- Moldova

- Monaco

- Morocco

- Niger

- Romania

- Rwanda

- St. Lucia

- São Tomé and Príncipe

- Senegal

- Seychelles

- Switzerland

- Togo

- Tunisia

- Vanuatu

- Vietnam

Observers 1 Associate member.

2 Provisionally referred to by the Francophonie as the "former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia"; see Macedonia naming dispute.Categories:- Saint Pierre and Miquelon

- Dependent territories in North America

- Northern American countries

- Special territories of the European Union

- Islands of the North Atlantic Ocean

- Member states of La Francophonie

- French-speaking countries

- Overseas departments, collectivities and territories of France

- States and territories established in 1946

- Territorial disputes of Canada

- Outline of Saint Pierre and Miquelon

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.