- Democratic Republic of the Congo

-

Coordinates: 2°52′48″S 23°39′22″E / 2.88°S 23.656°E

Democratic Republic of the Congo République Démocratique du Congo(French)

Repubilika ya Kongo Demokratika (Kituba)

Jamhuri ya Kidemokrasia ya Kongo (Swahili)

Republiki ya Kongó Demokratiki (Lingala)

Ditunga día Kongu wa Mungalaata (Tshiluba)

Flag Coat of Arms Motto: Justice – Paix – Travail

(French)

"Justice – Peace – Work"Anthem: "Debout Congolais"

(French)

"Arise, Congolese"Capital

(and largest city)Kinshasa

4°19′S 15°19′E / 4.317°S 15.317°EOfficial language(s) French Recognised national languages Lingala, Kikongo, Swahili, Tshiluba Demonym Congolese Government Semi-presidential republic - President Joseph Kabila - Prime Minister Adolphe Muzito Independence - from Belgium 30 June 1960[1] Area - Total 2,345,409 km2 (11th)

905,355 sq mi- Water (%) 4.3 Population - 2011 estimate 71,712,867[1] (19th) - Density 29.3/km2 (182nd)

75.9/sq miGDP (PPP) 2010 estimate - Total $23.117 billion[2] - Per capita $328[2] GDP (nominal) 2010 estimate - Total $13.125 billion[2] - Per capita $186[2] HDI (2011)  0.286[3] (low) (187th)

0.286[3] (low) (187th)Currency Congolese franc ( CDF)Time zone WAT, CAT (UTC+1 to +2) - Summer (DST) not observed (UTC+1 to +2) Drives on the right ISO 3166 code CD Internet TLD .cd Calling code 243 a Estimate is based on regression; other PPP figures are extrapolated from the latest International Comparison Programme benchmark estimates.  Kinshasa is the capital and largest city of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Part of the Congo River is in the background

Kinshasa is the capital and largest city of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Part of the Congo River is in the background

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (French: République démocratique du Congo) is a state located in Central Africa. It is the second largest country in Africa by area and the eleventh largest in the world. With a population of over 71 million,[1] the Democratic Republic of the Congo is the eighteenth most populous nation in the world, and the fourth most populous nation in Africa, as well as the most populous officially Francophone country.

It borders the Central African Republic and South Sudan to the north; Uganda, Rwanda, and Burundi in the east; Zambia and Angola to the south; the Republic of the Congo, the Angolan exclave of Cabinda, and the Atlantic Ocean to the west; and is separated from Tanzania by Lake Tanganyika in the east.[1] The country has access to the ocean through a 40-kilometre (25 mi) stretch of Atlantic coastline at Muanda and the roughly 9 km wide mouth of the Congo River which opens into the Gulf of Guinea.

The Second Congo War, beginning in 1998, devastated the country, involved seven foreign armies and is sometimes referred to as the "African World War".[4] Despite the signing of peace accords in 2003, fighting continues in the east of the country. In eastern Congo, the prevalence of rape and other sexual violence is described as the worst in the world.[5] The war is the world's deadliest conflict since World War II, killing 5.4 million people since 1998.[6][7] The vast majority died from malaria, diarrhea, pneumonia and malnutrition.[8]

The Democratic Republic of the Congo was formerly, in chronological order, the Congo Free State, Belgian Congo, Congo-Léopoldville, Congo-Kinshasa, and Zaire (Zaïre in French).[1] These former names are sometimes referred to, as unofficial names, with the exeption of Mobutu's discredited Zaire, along with various abreviations, such as, Congo, Congo-Kinshasa, DR Congo and DRC. Though it is located in the Central African UN subregion, the nation is also economically and regionally affiliated with Southern Africa as a member of the Southern African Development Community (SADC).

Contents

History

Early history

A wave of early people was identified in the northern and north-western parts of central Africa during the second millennium BC. They produced food (pearl millet), maintained domestic livestock and developed a kind of arboriculture mainly based on the oil palm. From 1,550 BC to 50 BC, starting from a nucleus area in south Cameroon on both banks of the Sanaga River, the first Neolithic peopling of northern and western central Africa can be followed south-eastwards and southwards.

In D.R. Congo, the first villages in the vicinity of Mbandaka and the Lake Tumba are known as the 'Imbonga Tradition', from around 650 BC. In Lower Congo, north of the Angolan border, it is the 'Ngovo Tradition' around 350 BC that shows the arrival of the Neolithic wave of advance.

In Kivu, across the country to the east, the 'Urewe Tradition' villages first appeared about 650 BC. The few archaeological sites known in Congo are a western extension of the 'Urewe' Culture which has been found chiefly in Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi and western Kenya and Tanzania. From the start of this tradition, the people knew iron smelting, as is evidenced by several iron-smelting furnaces excavated in Rwanda and Burundi.

The earliest evidence further to the west is known in Cameroon and near to the small town of Bouar in Central Africa. Though further studies are needed to establish a better chronology for the start of iron production in Central Africa, the Cameroonian data places iron smelting north of the Equatorial Forest around 650 BC to 550 BC. This technology developed independently from the previous Neolithic expansion, some 900 years later. As fieldwork done by a German team shows, the Congo River network was slowly settled by food-producing villagers going upstream in the forest. Work from a Spanish project in the Ituri area further east suggests villages reached there only around 1,150 BC.

The supposedly Bantu-speaking Neolithic and then iron-producing villagers added to and displaced the indigenous Pygmy populations (also known in the region as the "Batwa" or "Twa") into secondary parts of the country. Subsequent migrations from the Darfur and Kordofan regions of Sudan into the north-east, as well as East Africans migrating into the eastern Congo, added to the mix of ethnic groups. The Bantu-speakers imported a mixed economy made up of agriculture, small-stock raising, fishing, fruit collecting, hunting and arboriculture before 3,500 BP; iron-working techniques, possibly from West Africa, a much later addition. The villagers established the Bantu language family as the primary set of tongues for the Congolese.

The process in which the original Upemba society transitioned into the Kingdom of Luba was gradual and complex. This transition ran without interruption, with several distinct societies developing out of the Upemba culture prior to the genesis of the Luba. Each of these kingdoms became very wealthy due mainly to the region's mineral wealth, especially in ores. The civilization began to develop and implement iron and copper technology, in addition to trading in ivory and other goods. The Luba established a strong commercial demand for their metal technologies and were able to institute a long-range commercial net (the business connections extended over 1,500 kilometres (930 mi), all the way to the Indian Ocean). By the 16th century, the kingdom had an established strong central government based on chieftainship. The Eastern regions of the precolonial Congo were heavily disrupted by constant slave raiding, mainly from Arab/Zanzibari slave traders such as the infamous Tippu Tip.[9]

The African Congo Free State (1877–1908)

European exploration and administration took place from the 1870s until the 1920s. It was first led by Sir Henry Morton Stanley, who undertook his explorations under the sponsorship of King Leopold II of Belgium. Leopold had designs on what was to become the Congo as a colony.[10] In a succession of negotiations, Leopold – professing humanitarian objectives in his capacity as chairman of the Association Internationale Africaine – played one European rival against another.

Leopold formally acquired rights to the Congo territory at the Conference of Berlin in 1885 and made the land his private property and named it the Congo Free State.[10] Leopold's regime began various infrastructure projects, such as construction of the railway that ran from the coast to the capital of Leopoldville (now Kinshasa). It took years to complete. Nearly all such projects were aimed at increasing the capital which Leopold and his associates could extract from the colony, leading to exploitation of Africans.[11]

In the Free State, colonists brutalized the local population to produce rubber, for which the spread of automobiles and development of rubber tires created a growing international market. The sale of rubber made a fortune for Leopold, who built several buildings in Brussels and Ostend to honor himself and his country. To enforce the rubber quotas, the army, the Force Publique (FP), was called in. The Force Publique made the practice of cutting off the limbs of the natives as a means of enforcing rubber quotas a matter of policy; this practice was widespread. During the period of 1885–1908, millions of Congolese died as a consequence of exploitation and disease. In some areas the population declined dramatically, it has been estimated that sleeping sickness and smallpox killed nearly half the population in the areas surrounding the lower Congo River.[12] A government commission later concluded that the population of the Congo had been "reduced by half" during this period,[13] but determining precisely how many people died is impossible as no accurate records exist.

The actions of the Free State's administration sparked international protests led by British reporter Edmund Dene Morel and British diplomat/Irish rebel Roger Casement, whose 1904 report on the Congo condemned the practice. Famous writers such as Mark Twain and Arthur Conan Doyle also protested, and Joseph Conrad's novella Heart of Darkness was set in Congo Free State.

Belgian Congo (1908–1960)

In 1908, the Belgian parliament, despite initial reluctance, bowed to international pressure (especially that from Great Britain) and took over the Free State as a Belgian colony from the king. From then on, it was called the Belgian Congo and was under the rule of the elected Belgian government. The government improved significantly and a considerable economic and social progress was achieved. The white colonial rulers had, however, generally a condescending, patronizing attitude against the indigenous peoples, which led to bitter resentment.

During World War II, the Congolese army achieved several victories against the Italians in North Africa.

Political crisis (1960–1965)

In May 1960, a growing nationalist movement, the Mouvement National Congolais or MNC Party, led by Patrice Lumumba, won the parliamentary elections. The party appointed Lumumba as Prime Minister. The parliament elected Joseph Kasavubu, of the Alliance des Bakongo (ABAKO) party as President. Other parties that emerged included the Parti Solidaire Africain (or PSA) led by Antoine Gizenga, and the Parti National du Peuple (or PNP) led by Albert Delvaux and Laurent Mbariko. (Congo 1960, dossiers du CRISP, Belgium) The Belgian Congo achieved independence on 30 June 1960 under the name République du Congo ("Republic of Congo" or "Republic of the Congo" in English). Shortly after independence, the provinces of Katanga (led by Moise Tshombe) and South Kasai engaged in secessionist struggles against the new leadership.[14] Most of the 100,000 Europeans who had remained behind after independence fled the country,[15] opening the way for Congolese to replace the European military and administrative elite.[16]As the French colony of Middle Congo (Moyen Congo) also chose the name "Republic of Congo" upon achieving its independence, the two countries were more commonly known as "Congo-Léopoldville" and "Congo-Brazzaville", after their capital cities. Another way they were often distinguished during the 1960s, such as in newspaper articles, was that "Congo-Léopoldville" was called “The Congo” and "Congo-Brazzaville" was called simply “Congo.”

On 5 September 1960, Kasavubu dismissed Lumumba from office. Lumumba declared Kasavubu's action "unconstitutional" and a crisis between the two leaders developed. (cf. Sécession au Katanga – J.Gerald-Libois -Brussels- CRISP) Lumumba had previously appointed Joseph Mobutu chief of staff of the new Congo army, Armée Nationale Congolaise (ANC). Taking advantage of the leadership crisis between Kasavubu and Lumumba, Mobutu garnered enough support within the army to create mutiny. With financial support from the United States and Belgium, Mobutu paid his soldiers privately. The aversion of Western powers to communism and leftist ideology influenced their decision to finance Mobutu's quest to maintain "order" in the new state by neutralizing Kasavubu and Lumumba in a coup by proxy. A constitutional referendum after Mobutu's coup of 1965 resulted in the country's official name being changed to the "Democratic Republic of the Congo."[1] In 1971 it was changed again to "Republic of Zaïre."

On 17 January 1961, Katangan forces and Belgian paratroops – supported by the United States' and Belgium's intent on copper and diamond mines in Katanga and South Kasai – kidnapped and executed Patrice Lumumba. Amidst widespread confusion and chaos, a temporary government was led by technicians (Collège des Commissaires) with Evariste Kimba. The Katanga secession was ended in January 1963 with the assistance of UN forces. Several short-lived governments, of Joseph Ileo, Cyrille Adoula, and Moise Tshombe, took over in quick succession.

Zaire (1971–1997)

The new president Mobutu Sese Seko had the support of the United States because of his staunch opposition to Communism. Western powers appeared to believe this would make him a roadblock to Communist schemes in Africa.[citation needed]

A one-party system was established, and Mobutu declared himself head of state. He periodically held elections in which he was the only candidate. Relative peace and stability were achieved; however, Mobutu's government was guilty of severe human rights violations, political repression, a cult of personality and corruption. (Mobutu demanded every Congolese banknote printed with his image, hanging of his portrait in all public buildings, most businesses, and on billboards; and it was common for ordinary people to wear his likeness on their clothing.)

Corruption became so prevalent the term "le mal Zairois" or "Zairean Sickness" [17] was coined, reportedly by Mobutu himself.[citation needed] By 1984, Mobutu was said to have $4 billion (USD), an amount close to the country's national debt, deposited in a personal Swiss bank account. International aid, most often in the form of loans, enriched Mobutu while he allowed national infrastructure such as roads to deteriorate to as little as one-quarter of what had existed in 1960. With the embezzlement of government funds by Mobutu and his associates, Zaire became a "kleptocracy".

In a campaign to identify himself with African nationalism, starting on 1 June 1966, Mobutu renamed the nation's cities: Léopoldville became Kinshasa [the country was now Democratic Republic of The Congo – Kinshasa], Stanleyville became Kisangani, Elisabethville became Lubumbashi, and Coquihatville became Mbandaka. This renaming campaign was completed in the 1970s.

In 1971, Mobutu renamed the country the Republic of Zaire, its fourth name change in 11 years and its sixth overall. The Congo River was renamed the Zaire River. In 1972, Mobutu renamed himself Mobutu Sese Seko Kuku Ngbendu Wa Za Banga (translated as "the all powerful warrior who, because of his endurance and inflexible will to win, shall go from conquest to conquest, leaving fire in his wake"[18]).

During the 1970s and 1980s, Mobutu was invited to visit the United States on several occasions, meeting with U.S. Presidents Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush. In June 1989, Mobutu was the first African head of state invited for a state visit with newly elected President Bush.[19] Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, however, U.S. relations with Mobutu cooled, as he was no longer deemed necessary as a Cold War ally.

Opponents within Zaire stepped up demands for reform. This atmosphere contributed to Mobutu's declaring the Third Republic in 1990, whose constitution was supposed to pave the way for democratic reform. The reforms turned out to be largely cosmetic. Mobutu continued in power until the conflict forced him to flee Zaire in 1997. Thereafter, the nation chose to reclaim its name of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, since the name Zaire carried such strong connections to the rule of Mobutu.

Rwandan/Ugandan invasions and civil wars

By 1996, tensions from the neighbouring Rwandan Civil War and Rwandan Genocide had spilled over to Zaire. Rwandan Hutu militia forces (Interahamwe), who had fled Rwanda following the ascension of a Tutsi-led government, had been using Hutu refugees camps in eastern Zaire as a basis for incursion against Rwanda. These Hutu militia forces soon allied with the Zairian armed forces (FAZ) to launch a campaign against Congolese ethnic Tutsis in eastern Zaire.[20]

In turn, a coalition of Rwandan and Ugandan armies invaded Zaire under the cover of a small group of Tutsi militia to fight the Hutu militia, overthrow the government of Mobutu, and ultimately control the mineral resources of Zaire. They were soon joined by various Zairean politicians, who had been unsuccessfully opposing the dictatorship of Mobutu for many years, and now saw an opportunity for them in the invasion of Zaire by two of the region's strongest military forces.

This new expanded coalition of two foreign armies and some longtime opposition figures, led by Laurent-Désiré Kabila, became known as the Alliance des Forces Démocratiques pour la Libération du Congo-Zaïre (AFDL). They were seeking the broader goal of ousting Mobutu and controlling his country's wealth. In May 1997, Mobutu fled the country and Kabila marched into Kinshasa, naming himself president and reverting the name of the country to the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Civilians waiting to cross the DRC-Rwanda border (2001). By 2008 the Second Congo War and its aftermath had killed 5.4 million people.[21]

Civilians waiting to cross the DRC-Rwanda border (2001). By 2008 the Second Congo War and its aftermath had killed 5.4 million people.[21]

A few months later, President Laurent-Désiré Kabila thanked all the foreign military forces that helped him to overthrow Mobutu, and asked them to return back to their countries because he was very fearful and concerned that the Rwandan military officers who were running his army were plotting a coup d'état against him in order to give the presidency to a Tutsi who would report directly to the President of Rwanda, Paul Kagame. This move was not well received by the Rwandan and Ugandan governments, who wanted to control their big neighbour.

Consequently, Rwandan troops in DRC retreated to Goma and launched a new militia group or rebel movement called the Rassemblement Congolais pour la Democratie (RCD), led by Tutsis, to fight against their former ally, President Laurent-Désiré Kabila. To counterbalance the power and influence of Rwanda in DRC, the Ugandan troops instigated the creation of another rebel movement called the Movement for the Liberation of Congo (MLC), led by the Congolese warlord Jean-Pierre Bemba, son of Congolese billionaire Bemba Saolona. The two rebel movements started the second war by attacking the DRC's still fragile army in 1998, backed by Rwandan and Ugandan troops. Angola, Zimbabwe and Namibia became involved militarily on the side of the government to defend a fellow SADC member.

Kabila was assassinated in 2001 and was succeeded by his son Joseph, who upon taking office called for multilateral peace talks to end the war. In February 2001 a peace deal was brokered between Kabila, Rwanda and Uganda, leading to the apparent withdrawal of foreign troops. UN peacekeepers, MONUC, arrived in April 2001. The conflict was reignited in January 2002 by ethnic clashes in the northeast, and both Uganda and Rwanda then halted their withdrawal and sent in more troops. Talks between Kabila and the rebel leaders led to the signing of a peace accord in which Kabila would share power with former rebels. By June 2003 all foreign armies except those of Rwanda had pulled out of Congo. Much of the conflict was focused on gaining control of substantial natural resources in the country, including diamonds, copper, zinc, and coltan.[22]

DR Congo had a transitional government until the election was over. A constitution was approved by voters, and on 30 July 2006 the Congo held its first multi-party elections since independence in 1960. After this Joseph Kabila took 45% of the votes and his opponent, Jean-Pierre Bemba took 20%. The disputed results of this election turned into an all-out battle between the supporters of the two parties in the streets of the capital, Kinshasa, from 20–22 August 2006 . Sixteen people died before police and the UN mission MONUC took control of the city. A new election was held on 29 October 2006, which Kabila won with 70% of the vote. Bemba made multiple public statements saying the election had "irregularities," despite the fact that every neutral observer praised the elections. On 6 December 2006 the Transitional Government came to an end as Joseph Kabila was sworn in as President.

The fragility of the state government has allowed continued conflict and human rights abuses. In the ongoing Kivu conflict, the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR) continues to threaten the Rwandan border and the Banyamulenge; Rwanda supports RCD-Goma rebels against Kinshasa; a rebel offensive at the end of October 2008 caused a refugee crisis in Ituri, where MONUC has proved unable to contain the numerous militia and groups driving the Ituri conflict. In the northeast, Joseph Kony's LRA moved from their original bases in Uganda (where they have fought a 20-year rebellion) and South Sudan to DR Congo in 2005 and set up camps in the Garamba National Park.[23][24] In northern Katanga, the Mai-Mai created by Laurent Kabila slipped out of the control of Kinshasa. The war is the world's deadliest conflict since World War II, killing 5.4 million people.[6]

Impact of armed conflict on civilians

In 2009, people in the Congo may still be dying at a rate of an estimated 45,000 per month,[25] and estimates of the number who have died from the long conflict range from 900,000 to 5,400,000.[26] The death toll is due to widespread disease and famine; reports indicate that almost half of the individuals who have died are children under the age of 5. This death rate has prevailed since efforts at rebuilding the nation began in 2004.[27]

The long and brutal conflict in the DRC has caused massive suffering for civilians, with estimates of millions dead either directly or indirectly as a result of the fighting. There have been frequent reports of weapon bearers killing civilians, destroying property, committing widespread sexual violence,[28] causing hundreds of thousands of people to flee their homes or otherwise breaching humanitarian and human rights law. An estimated 200,000 women have been raped.[29]

Few people in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) have been unaffected by the armed conflict. A survey conducted in 2009 by the ICRC and Ipsos shows that three quarters (76%) of the people interviewed have been affected in some way–either personally or due to the wider consequences of armed conflict.[30]

In 2003, Sinafasi Makelo, a representative of Mbuti pygmies, told the UN's Indigenous People's Forum that during the war, his people were hunted down and eaten as though they were game animals. In neighbouring North Kivu province there has been cannibalism by a group known as Les Effaceurs ("the erasers") who wanted to clear the land of people to open it up for mineral exploitation.[31] Both sides of the war regarded them as "subhuman" and some say their flesh can confer magical powers.[32]

International Community Response

The response of the international community has been incommensurate with the scale of the disaster resulting from the war in the Congo. Its support for political and diplomatic efforts to end the war has been relatively consistent, but it has taken no effective steps to abide by repeated pledges to demand accountability for the war crimes and crimes against humanity that were routinely committed in Congo. United Nations Security Council and the U.N. Secretary-General have frequently denounced human rights abuses and the humanitarian disaster that the war unleashed on the local population. But they had shown little will to tackle the responsibility of occupying powers for the atrocities taking place in areas under their control, areas where the worst violence in the country took place. Hence Rwanda, like Uganda, has escaped any significant sanction for its role. [33]

Geography

The Congo is situated at the heart of sub-Saharan Africa and is bounded by (clockwise from the southwest) Angola, the South Atlantic Ocean, the Republic of Congo, the Central African Republic, South Sudan, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, Tanzania across Lake Tanganyika, and Zambia. The country lies between latitudes 6°N and 14°S, and longitudes 12° and 32°E. It straddles the Equator, with one-third to the North and two-thirds to the South. The size of Congo, 2,345,408 square kilometres (905,567 sq mi), is slightly greater than the combined areas of Spain, France, Germany, Sweden, and Norway.

As a result of its equatorial location, the Congo experiences high precipitation and has the highest frequency of thunderstorms in the world. The annual rainfall can total upwards of 80 inches (2,000 mm) in some places, and the area sustains the Congo Rainforest, the second largest rain forest in the world (after that of the Amazon). This massive expanse of lush jungle covers most of the vast, low-lying central basin of the river, which slopes toward the Atlantic Ocean in the west. This area is surrounded by plateaus merging into savannas in the south and southwest, by mountainous terraces in the west, and dense grasslands extending beyond the Congo River in the north. High, glaciated mountains are found in the extreme eastern region.

The tropical climate has also produced the Congo River system which dominates the region topographically along with the rainforest it flows through, though they are not mutually exclusive. The name for the Congo state is derived in part from the river. The river basin (meaning the Congo River and all of its myriad tributaries) occupies nearly the entire country and an area of nearly 1,000,000 km2 (390,000 sq mi). The river and its tributaries (major offshoots include the Kasai, Sangha, Ubangi, Aruwimi, and Lulonga) form the backbone of Congolese economics and transportation. They have a dramatic impact on the daily lives of the people.

The sources of the Congo are in the highlands and mountains of the East African Rift, as well as Lake Tanganyika and Lake Mweru. The river flows generally west from Kisangani just below Boyoma Falls, then gradually bends southwest, passing by Mbandaka, joining with the Ubangi River, and running into the Pool Malebo (Stanley Pool). Kinshasa and Brazzaville are on opposite sides of the river at the Pool (see NASA image).

Then the river narrows and falls through a number of cataracts in deep canyons (collectively known as the Livingstone Falls), and then running past Boma into the Atlantic Ocean. The river also has the second-largest flow and the second-largest watershed of any river in the world (trailing the Amazon in both respects). The river and a 45 km wide strip of land on its north bank provide the country's only outlet to the Atlantic.

The previously mentioned Great Rift Valley, in particular the Eastern Rift, plays a key role in shaping the Congo's geography. Not only is the northeastern section of the country much more mountainous, but due to the rift's tectonic activities, this area also experiences volcanic activity, occasionally with loss of life. The geologic activity in this area also created the famous African Great Lakes, three of which lie on the Congo's eastern frontier: Lake Albert (known previously as Lake Mobutu), Lake Edward, and Lake Tanganyika.

The Rift Valley has exposed an enormous amount of mineral wealth throughout the south and east of the Congo, making it accessible to mining. Cobalt, copper, cadmium, industrial and gem-quality diamonds, gold, silver, zinc, manganese, tin, germanium, uranium, radium, bauxite, iron ore, and coal are all found in plentiful supply, especially in the Congo's southeastern Katanga region.

On 17 January 2002 Mount Nyiragongo erupted in Congo, with the lava running out at 40 mph (64 km/h) and 50 yards (46 m) wide. One of the three streams of extremely fluid lava flowed through the nearby city of Goma, killing 45 and leaving 120,000 homeless. Four hundred thousand people were evacuated from the city during the eruption. The lava poisoned the water of Lake Kivu, killing fish. Only two planes left the local airport because of the possibility of the explosion of stored petrol. The lava passed the airport but ruined the runway, entrapping several airplanes. Six months after the 2002 eruption, nearby Mount Nyamulagira also erupted. Mount Nyamulagira also erupted in 2006 and again in January 2010. Both of these active volcanos are located within the boundaries of Virunga National Park.

World Wide Fund for Nature ecoregions located in the Congo include:

- Central Congolian lowland forests – home to the rare bonobo primate

- The Eastern Congolian swamp forests along the Congo River

- The Northeastern Congolian lowland forests, with one of the richest concentrations of primates in the world

- Southern Congolian forest-savanna mosaic

- A large section of the Central Zambezian Miombo woodlands

- The Albertine Rift montane forests region of high forest runs along the eastern borders of the country.

World Heritage Sites located in Democratic Republic of Congo are: Virunga National Park (1979), Garamba National Park (1980), Kahuzi-Biega National Park (1980), Salonga National Park (1984) and Okapi Wildlife Reserve (1996).

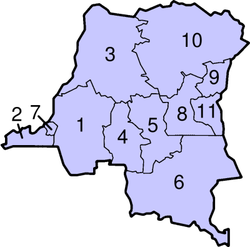

Provinces

Main articles: Provinces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Districts of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Territories of the Democratic Republic of the CongoThe country is divided into 10 provinces and one city-province:[1]

- Bandundu

- Bas-Congo

- Équateur

- Kasai-Occidental

- Kasai-Oriental

- Katanga

- Kinshasa (city-province)

- Maniema

- Nord-Kivu

- Orientale

- Sud-Kivu

- An Ituri Interim Administration also exists in the Ituri region of Orientale Province

The provinces are subdivided into districts which are divided into territories.

- Population of major cities (2008)

City Population (2008) Kinshasa 7,500,000 Mbuji-Mayi 2,500,000 Lubumbashi 1,700,000 Kananga 1,400,000 Kisangani 1,200,000 Kolwezi 1,100,000 Mbandaka 850,000 Likasi 600,000 Boma 600,000 Government

After a four-year interim between two constitutions that established new political institutions at the various levels of all branches of government, as well as new administrative divisions for the provinces throughout the country, politics in the Democratic Republic of the Congo have finally settled into a stable presidential democratic republic. The 2003 transitional constitution[34] established a system composed of a bicameral legislature with a Senate and a National Assembly. The Senate had, among other things, the charge of drafting the new constitution of the country. The executive branch was vested in a 60-member cabinet, headed by a President and four vice presidents. The President was also the Commander-in Chief of the Armed forces. The unusual organization of the executive — considering the large number of vice presidents — had earned it the very official nickname of "The 1 + 4".[citation needed]

The transition constitution also established a relatively independent judiciary, headed by a Supreme Court with constitutional interpretation powers.

The 2006 constitution, also known as the Constitution of the Third Republic, came into effect in February 2006. It had concurrent authority, however, with the transitional constitution until the inauguration of the elected officials who emerged from the July 2006 elections. Under the new constitution, the legislature remained bicameral; the executive was concomitantly undertaken by a President and the government, led by a Prime Minister, appointed from the party with the majority at the National Assembly. The government – not the President – is responsible to the Parliament.

The new constitution also granted new powers to the provincial governments with the creation of provincial parliaments, which have oversight over the Governor, head of the provincial government, whom they elect.

The new constitution also saw the disappearance of the Supreme Court, which was divided into three new institutions. The constitutional interpretation prerogative of the Supreme Court is now held by the Constitutional Court.

Corruption

Mobutu Sese Seko ruled Zaire from 1965 to 1997. A relative explained how the government illicitly collected revenue: "Mobutu would ask one of us to go to the bank and take out a million. We'd go to an intermediary and tell him to get five million. He would go to the bank with Mobutu's authority, and take out ten. Mobutu got one, and we took the other nine."[35] Mobutu institutionalized corruption to prevent political rivals from challenging his control, leading to an economic collapse in 1996.[36] Mobutu allegedly stole up to US$4 billion while in office;[37] in July 2009, a Swiss court determined that the statute of limitations had run out on an international asset recovery case of about $6.7 million of deposits of Mobutu's in a Swiss bank, and therefore the assets should be returned to Mobutu's family.[38]

President Joseph Kabila established the Commission of Repression of Economic Crimes upon his ascension to power in 2001.[39]

- Corruption Perception Index

Main article: Corruption Perception IndexYear Ranking Countries ranked Rating 2004 133 145 2.0[40] – 2005 144 158 2.1[41] – 2006 156 163 2.0[42] – 2007 168 179 1.9[43] – 2008 171 180 1.7[44] – In 2006 Transparency International ranked the Democratic Republic of the Congo 156 out of 163 countries in the Corruption Perception Index, tying Bangladesh, Chad, and Sudan with a 2.0 rating.[45]

Foreign relations and military

See also: Foreign relations of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Military of the Democratic Republic of the Congo

The global growth in demand for scarce raw materials and the industrial surges in China, India, Russia, Brazil and other developing countries require that developed countries employ new, integrated and responsive strategies for identifying and ensuring, on a continual basis, an adequate supply of strategic and critical materials required for their security needs. Highlighting the DR Congo's importance to US national security, the effort to establish an elite Congolese unit is the latest push by the U.S. to professionalize armed forces in this strategically important region.

There are economic and strategic incentives to bringing more security to the Congo, which is rich in natural resources such as cobalt. Cobalt is a strategic and critical metal used in many diverse industrial and military applications. The largest use of cobalt is in superalloys, which are used to make jet engine parts. Cobalt is also used in magnetic alloys and in cutting and wear-resistant materials such as cemented carbides. The chemical industry consumes significant quantities of cobalt in a variety of applications including catalysts for petroleum and chemical processing; drying agents for paints and inks; ground coats for porcelain enamels; decolorizers for ceramics and glass; and pigments for ceramics, paints, and plastics. The country contains 80 percent of the world’s cobalt reserves.[46]

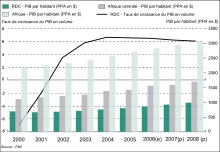

Economy

Although citizens of the DRC are among the poorest in the world, having the second lowest nominal GDP per capita, the Democratic Republic of Congo is widely considered to be the richest country in the world regarding natural resources; its untapped deposits of raw minerals are estimated to be worth in excess of US$ 24 trillion.[47][48][49]

The economy of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, a nation endowed with resources of vast potential wealth, has declined drastically since the mid-1980s. At the time of its independence in 1960, DRC was the second most industrialized country in Africa after South Africa, it boasted a thriving mining sector and its agriculture sector was relatively productive.[50] The two recent conflicts (the First and Second Congo Wars), which began in 1996, have dramatically reduced national output and government revenue, have increased external debt, and have resulted in deaths of more than five million people from war, and associated famine and disease. Malnutrition affects approximately two thirds of the country's population.

Foreign businesses have curtailed operations due to uncertainty about the outcome of the conflict, lack of infrastructure, and the difficult operating environment. The war has intensified the impact of such basic problems as an uncertain legal framework, corruption, inflation, and lack of openness in government economic policy and financial operations.

Conditions improved in late 2002 with the withdrawal of a large portion of the invading foreign troops. A number of International Monetary Fund and World Bank missions have met with the government to help it develop a coherent economic plan, and President Joseph Kabila has begun implementing reforms. Much economic activity lies outside the GDP data. A United Nations Human Development Index report shows human development to be one of the worst in decades.

The economy of the second largest country in Africa relies heavily on mining. However, the smaller-scale economic activity occurs in the informal sector and is not reflected in GDP data.[51] The largest mines in the Congo are located in the Shaba province, in the South. The Congo is the world's largest producer of cobalt ore,[52] and a major producer of copper and industrial diamonds, the latter coming from the Kasai province in the West. The Congo has 70% of the world’s coltan, and more than 30% of the world’s diamond reserves.,[53] mostly in the form of small, industrial diamonds. The coltan is a major source of tantalum, which is used in the fabrication of electronic components in computers and mobile phones. In 2002, tin was discovered in the east of the country, but, to date, mining has been on a small scale.[54] Smuggling of the conflict minerals, coltan and cassiterite (ores of tantalum and tin, respectively), has helped fuel the war in the Eastern Congo. Katanga Mining Limited, a Swiss-owned company, owns the Luilu Metallurgical Plant, which has a capacity of 175,000 tonnes of copper and 8,000 tonnes of cobalt per year, making it the largest cobalt refinery in the world. After a major rehabilitation program, the company restarted copper production in December 2007 and cobalt production in May 2008.[55] The Democratic Republic of Congo also possesses 50 percent of Africa’s forests and a river system that could provide hydro-electric power to the entire continent, according to a U.N. report on the country’s strategic significance and its potential role as an economic power in central Africa.[56] It has one of the twenty last ranks among the countries on the Corruption Perception Index.

In 2007, The World Bank decided to grant the Democratic Republic of Congo up to $1.3 billion in assistance funds over the next three years.[57]

The Democratic Republic of Congo is in the process of becoming a member of the Organization for the Harmonization of Business Law in Africa (OHADA).[58]

Demographics

The United Nations 2007 estimated the population at 62.6 million people, having increased rapidly despite the war from 46.7 million in 1997. As many as 250 ethnic groups have been identified and named. The most numerous people are the Kongo, Luba, and Mongo. About 600,000 Pygmies are the aboriginal people of the DR Congo.[59] Although several hundred local languages and dialects are spoken, the linguistic variety is bridged both by widespread use of French and intermediary languages such as Kongo, Tshiluba, Swahili, and Lingala.

Migration

Given the situation in the country and the condition of state structures, it is extremely difficult to obtain reliable data. However, evidence suggests that DRC continues to be a destination country for immigrants in spite of recent declines. Immigration is seen to be very diverse in nature, with refugees and asylum-seekers – products of the numerous and violent conflicts in the Great Lakes Region – constituting an important subset of the population in the country. Additionally, the country’s large mine operations attract migrant workers from Africa and beyond and there is considerable migration for commercial activities from other African countries and the rest of the world, but these movements are not well studied. Transit migration towards South Africa and Europe also plays a role. Immigration in the DRC has decreased steadily over the past two decades, most likely as a result of the armed violence that the country has experienced. According to the International Organization for Migration, the number of immigrants in the DRC has declined from just over 1 million in 1960, to 754,000 in 1990, to 480,000 in 2005, to an estimated 445,000 in 2010. Valid figures are not available on migrant workers in particular, partly due to the predominance of the informal economy in the DRC. Data are also lacking on irregular immigrants, however given neighbouring country ethnic links to nationals of the DRC, irregular migration is assumed to be a significant phenomenon in the country.[60]

Figures on the number of Congolese nationals abroad vary greatly depending on the source, from 3 to 6 million. This discrepancy is due to a lack of official, reliable data. Emigrants from the DRC are above all long-term emigrants, the majority of which live within Africa and to a lesser extent in Europe; 79.7% and 15.3% respectively, according to estimates on 2000 data. New destination countries include South Africa and various points en route to Europe. In addition to being a host country, the DRC has also produced a considerable number of refugees and asylum-seekers located in the region and beyond. These numbers peaked in 2004 when, according to UNHCR, there were more than 460,000 refugees from the DRC; in 2008, Congolese refugees numbered 367,995 in total, 68% of which were living in other African countries.[60]

Status of women

Further information: Sexual violence in the Democratic Republic of the CongoThe United Nations Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women in 2006 expressed concern that in the post-war transition period, the promotion of women’s human rights and gender equality is not seen as a priority.[61]

In eastern Congo, the prevalence and intensity of rape and other sexual violence is described as the worst in the world.[5] A 2006 report by the African Association for the Defence of Human Rights prepared for that committee provides a broad overview of issues confronting women in the DRC in law and in daily life.[62]

The war has made the life of women more precarious. Violence against women seems to be perceived by large sectors of society to be normal.[63] In July 2007, the International Committee of the Red Cross expressed concern about the situation in eastern DRC.[64] A phenomenon of 'pendulum displacement' has developed, where people hasten at night to safety. According to the UN Special Rapporteur on Violence, Yakin Ertürk, who toured eastern Congo in July 2007, violence against women in North and South Kivu included 'unimaginable brutality'. 'Armed groups attack local communities, loot, rape, kidnap women and children, and make them work as sexual slaves,' Ertürk said.[65]

In December 2008 GuardianFilms of The Guardian newspaper released a film documenting the testimony of over 400 women and girls who had been abused by marauding militia.[66]

In June 2010, UK aid group Oxfam reported a dramatic increase in the number of rapes occurring in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. While researchers from Harvard discovered that rapes committed by civilians had increased by seventeenfold.[67]

Religion

Christianity is the majority religion in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, followed by about 96% of the population. Animism accounts for 0.7%.[68]

Kimbanguism was seen as a threat to the colonial regime and was banned by the Belgians. Kimbanguism, officially "the church of Christ on Earth by the prophet Simon Kimbangu", now has about three million members,[69] primarily among the Bakongo of Bas-Congo and Kinshasa.

The largest concentration of Christians following William Branham is in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where it is estimated that there are up to 2,000,000 followers.[citation needed]

Sixty-two of the Protestant denominations in the country are federated under the umbrella of the Church of Christ in Congo or CCC (in French, Église du Christ au Congo or ECC). It is often simply referred to as 'The Protestant Church', since it covers most of the 35% of the population who are Protestants.

Islam in the Democratic Republic of the Congo accounts for 1.5% of the population.[68] The rest follow traditional beliefs, syncretic sects or Hinduism. Islam was introduced and mainly spread by Arab traders/merchants.[70] Traditional religions embody such concepts as monotheism, animism, vitalism, spirit and ancestor worship, witchcraft, and sorcery and vary widely among ethnic groups. The syncretic sects often merge elements of Christianity with traditional beliefs and rituals and are not recognized by mainstream churches as part of Christianity.[citation needed] Under the weight of poverty, superstitious tradition is taken advantage of in the socially acceptable practice of children being accused of witchcraft and sent away from homes and family. The usual term for these children is enfants sorciers (child witches) or enfants dits sorciers (children accused of witchcraft) and can lead to physical violence against these children.[71] Non-denominational church organizations have been formed to capitalize on this belief by charging exorbitant fees for exorcisms. Though recently outlawed, children have been subjected to often-violent abuse at the hands of self-proclaimed prophets and priests. [72]

In 2002, USAID funded the production of two short films on the subject, made in Kinshasa by journalists Angela Nicoara and Mike Ormsby.[73]

Languages

French is the official language of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It is meant to be an ethnically neutral language, to ease communication among the many different ethnic groups of the Congo.

There are an estimated total of 242 languages spoken in the country. Out of these, only four have the status of national languages: Kikongo (Kituba), Lingala, Tshiluba and Swahili (most spoken in the DRC).

Lingala was made the official language of the colonial army, the "Force Publique" under Belgian colonial rule. But since the recent rebellions, a good part of the army in the East also uses Swahili where it is prevalent.

When the country was a Belgian colony, it had already instituted teaching and use of the four national languages in primary schools, making it one of the few African nations to have had literacy in local languages during the European colonial period. During the colonial period both Dutch and French were the official languages but French was by far the most important.

About 24,320,000 people of DRC speak French either as a first or second language.

Health

Main article: Health in the Democratic Republic of the CongoCongo has the world's second-highest rate of infant mortality (after Chad). In Eastern Congo there are still unrest and fighting among tribal and also warlord armies to control diamonds and other minerals. More than a quarter of the 500,000 children under 5 years of ages worldwide (more than 125,000 of them) are Congolese children who die from pneumococcus bacterium. In April 2011, through aid from Global Alliance for Vaccines, a new vaccine to prevent pneumococcal disease was introduced around Kinshasa.[74]

Culture

The culture of the Democratic Republic of the Congo reflects the diversity of its hundreds of ethnic groups and their differing ways of life throughout the country — from the mouth of the River Congo on the coast, upriver through the rainforest and savanna in its centre, to the more densely populated mountains in the far east. Since the late 19th century, traditional ways of life have undergone changes brought about by colonialism, the struggle for independence, the stagnation of the Mobutu era, and most recently, the First and Second Congo Wars. Despite these pressures, the customs and cultures of the Congo have retained much of their individuality. The country's 60 million inhabitants are mainly rural. The 30 percent who live in urban areas have been the most open to Western influences.

Another notable feature in Congo culture is its sui generis music. The DROC has blended its ethnic musical sources with Cuban rumba, and merengue to give birth to soukous. Influential figures of soukous and its offshoots: N'dombolo and Rumba rock, are Grand Kalle, Dr. Nico, Franco Luambo, Tabu Ley, Lutumba Simaro, Papa Wemba, King Kester Emeneya, Tshala Muana Koffi Olomide, JB Mpiana, Werrason, Kanda Bongo, Ray Lema, Mpongo Love, Abeti Masikini, Reddy Amisi, [Pasnas] Pepe Kalle, Fally Ipupa, Awilo Longomba, Gatho Buvens, Ferre Gola and Nyoka Longo.

Other African nations produce music genres that are derived from Congolese soukous. Some of the African bands sing in Lingala, one of the main languages in the DRC. The same Congolese soukous, under the guidance of "le sapeur", Papa Wemba, has set the tone for a generation of young men always dressed up in expensive designers' clothes', they became to be known as the 4th generation of the congolese music and they mostly come from the former well knwon band Wenge Musica.

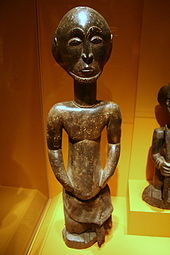

The Congo is also known for its art. Traditional art includes masks and wooden statues. Notable contemporary artists and fashion designers are Odette Maniema Krempin, Lema Kusa, Henri Kalama Akulez, Nshole, Mavinga, Claudy Khan et Chéri Samba.

Education

In 2001 the literacy rate was estimated to be 67.2% (80.9% male and 54.1% female).[75] The education system in the Democratic Republic of the Congo is governed by three government ministries: the Ministère de l’Enseignement Primaire, Secondaire et Professionnel (MEPSP), the Ministère de l’Enseignement Supérieur et Universitaire (MESU) and the Ministère des Affaires Sociales (MAS). The educational system in the DRC is similar to that of Belgium. In 2002, there were over 19,000 primary schools serving 160,000 students; and 8,000 secondary schools serving 110,000 students.

However, primary school education in the Democratic Republic of the Congo is neither compulsory, free nor universal, and many children are not able to go to school because parents are unable to pay the enrollment fees.[76] Parents are customarily expected to pay teachers' salaries.[76] In 1998, the most recent year for which data are available, the gross primary enrollment rate was 50 percent.[76]

Gross enrollment ratios are based on the number of students formally registered in primary school and therefore do not necessarily reflect actual school attendance.[76] In 2000, 65 percent of children ages 10 to 14 years were attending school.[76] As a result of the 6-year civil war, over 5.2 million children in the country receive no education.[76]

Flora and fauna

The rainforests of the Democratic Republic of the Congo contain great biodiversity, including many rare and endemic species, such as the common chimpanzee and the bonobo (formerly known as the Pygmy Chimpanzee), the forest elephant, mountain gorilla, okapi and white rhino. Five of the country's national parks are listed as World Heritage Sites: the Garumba, Kahuzi-Biega, Salonga and Virunga National Parks, and the Okapi Wildlife Reserve. The civil war and resultant poor economic conditions have endangered much of this biodiversity. Many park wardens were either killed or could not afford to continue their work. All five sites are listed by UNESCO as World Heritage In Danger. The Democratic Republic of the Congo is the most biodiverse African country.[77] The Democratic Republic of Congo is also home to some cryptids, such as Mokele mbembe[78] [79] [80]

Over the past century or so, the DRC has developed into the center of what has been called the Central African "bushmeat" problem, which is regarded by many as a major environmental, as well as, socio-economic crisis. "Bushmeat" is another word for the meat of wild animals. It is typically obtained through trapping, usually with wire snares, or otherwise with shotguns, poisoned arrows or arms originally intended for use in the DRC's numerous military conflicts.

The "bushmeat crisis" has emerged in the DRC mainly as a result of the poor living conditions of the Congolese people and a lack of education about the dangers of eating it. A rising population combined with deplorable economic conditions has forced many Congolese to become dependent on bushmeat, either as a means of acquiring income (hunting the meat and selling), or are dependent on it for food. Unemployment and urbanization throughout Central Africa have exacerbated the problem further by turning cities like the urban sprawl of Kinshasa into the prime market for commercial bushmeat. This combination has caused not only widespread endangerment of local fauna, but has forced humans to trudge deeper into the wilderness in search of the desired animal meat. This overhunting results in the deaths of more animals and makes resources even more scarce for humans. The hunting has also been facilitated by the extensive logging prevalent throughout the Congo's rainforests (from corporate logging, in addition to farmers clearing out forest for agriculture), which allows hunters much easier access to previously unreachable jungle terrain, while simultaneously eroding away at the habitats of animals.[81] Deforestation is accelerating in Central Africa.[82]

A case that has particularly alarmed conservationists is that of primates. The Congo is inhabited by three distinct great ape species — the Common chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes), the bonobo (Pan paniscus) and the gorilla. It is the only country in the world in which bonobos are found in the wild. The chimpanzee and bonobo are the closest living evolutionary relatives to humans.

Much concern has been raised about Great ape extinction. Because of hunting and habitat destruction, the chimpanzee and the gorilla, both of whose population once numbered in the millions, have now dwindled down to only about 200,000[83] gorillas, 100,000[84] chimpanzees and possibly only about 10,000 [84] bonobos. Gorillas, chimpanzees, and bonobos are all classified as Endangered by the World Conservation Union, as well as the okapi, which is also native to the area geography.

Transport

Ground transport in the Democratic Republic of Congo has always been difficult. The terrain and climate of the Congo Basin present serious barriers to road and rail construction, and the distances are enormous across this vast country. Furthermore, chronic economic mismanagement and internal conflict has led to serious under-investment over many years.

On the other hand, the Democratic Republic of Congo has thousands of kilometres of navigable waterways, and traditionally water transport has been the dominant means of moving around approximately two-thirds of the country.

All air carriers certified by the Democratic Republic of the Congo have been banned from European Union airports by the European Commission, because of inadequate safety standards.[85]

See also

- Outline of the Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Index of Democratic Republic of the Congo-related articles

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Central Intelligence Agency (2011). "Congo, Democratic Republic of the". The World Factbook. Langley, Virginia: Central Intelligence Agency. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/nu.html. Retrieved 2011-10-05.

- ^ a b c d "Democratic Republic of the Congo". International Monetary Fund. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2011/01/weodata/weorept.aspx?pr.x=76&pr.y=6&sy=2008&ey=2011&scsm=1&ssd=1&sort=country&ds=.&br=1&c=636&s=NGDPD%2CNGDPDPC%2CPPPGDP%2CPPPPC%2CLP&grp=0&a=. Retrieved 2011-04-21.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2011". United Nations. 2011. http://hdr.undp.org/en/media/HDR_2011_EN_Table1.pdf. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

- ^ See "Rumblings of war in heart of Africa" by Abraham McLaughlin and Duncan Woodside The Christian Science Monitor 23 June 2004 and "World War Three" by Chris Bowers My Direct Democracy 24 July 2006

- ^ a b McCrummen, Stephanie (2007-09-09). "Prevalence of Rape in E.Congo Described as Worst in World". Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/09/08/AR2007090801194.html. Retrieved 2010-05-02.

- ^ a b Robinson, Simon (2006-05-28). "The deadliest war in the world". Time.com. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1198921,00.html. Retrieved 2010-05-02.

- ^ Bavier, Joe (2008-01-22). "Congo War driven crisis kills 45,000 a month". Reuters. http://www.reuters.com/article/worldNews/idUSL2280201220080122. Retrieved 2010-05-02.

- ^ Report on the crisis Full report at IRC Mortality Facts from the International Rescue Committee

- ^ The East African slave trade. BBC World Service | The Story of Africa.

- ^ a b Keyes, Michael. The Congo Free State – a colony of gross excess. September 2004.

- ^ Hochschild, Adam (1999), King Leopold's Ghost, Mariner Books.

- ^ "The Cambridge history of Africa: From the earliest times to c. 500 BC". John D. Fage (1982). Cambridge University Press. p.748. ISBN 0-521-22803-4

- ^ King Leopold's Ghost, Adam Hochschild (1999) ISBN 0-618-00190-5 Houghton Mifflin Books

- ^ "Jungle Shipwreck". Time. 25 July 1960

- ^ "UN". Historylearningsite.co.uk. 2007-03-30. http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/united_nations_congo.htm. Retrieved 2010-05-02.

- ^ "Hearts of Darkness", allacademic.com

- ^ ""Zaire: The Hoax of Independence," The Aida Parker Newsletter #203, 4 August 1997". cycad.com. http://www.cycad.com/cgi-bin/Aida/203/203_zaire.html.

- ^ Gbadolite, Adam Zagorin (February 22, 1993). "Leaving Fire in His Wake: MOBUTU SESE SEKO". Time magazine. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,977788,00.html. Retrieved 19 October 2011.

- ^ "Zaire's Mobutu Visits America," by Michael Johns, Heritage Foundation Executive Memorandum #239, 29 June 1989.[dead link]

- ^ Thom, William G. "Congo-Zaire's 1996–97 civil war in the context of evolving patterns of military conflict in Africa in the era of independence." Conflict Studies Journal at the University of New Brunswick, Vol. XIX No. 2, Fall 1999.

- ^ "Congo war-driven crisis kills 45,000 a month-study". Reuters. 2008-01-22. http://www.alertnet.org/thenews/newsdesk/L22802012.htm.[dead link]

- ^ "Country Profiles". BBC News. 2010-02-10. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/country_profiles/1076399.stm. Retrieved 2010-05-02.

- ^ Fessy, Thomas (2008-10-23). "Congo terror after LRA rebel raids". BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/7685235.stm. Retrieved 2010-05-02.

- ^ "thousands flee LRA in DR Congo". BBC News. 2008-09-25. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/7635719.stm. Retrieved 2010-05-02.

- ^ Orphaned, Raped and Ignored, Nicholas D. Kristof. New York Times, 31 January 2010

- ^ A New Study Finds Death Toll in Congo War too High, James Butty. VOA News, 21 January 2010

- ^ Polgreen, Lydia (23 January 2008). "Congo's Death Rate Unchanged Since War Ended". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2008/01/23/world/africa/23congo.html. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- ^ "IHL and Sexual Violence". The Program for Humanitarian Policy and Conflict Research.

- ^ "The victims' witness". The Guardian. 9 May 2008.

- ^ DRC, Opinion survey 2009, by ICRC and Ipsos

- ^ Pygmies struggle to survive. Times Online. 16 December 2004.

- ^ DR Congo Pygmies 'exterminated'. BBC News. 6 July 2004.

- ^ "Human Rights Watch: War Crimes in Kisangani". Hrw.org. 2002-08-20. http://www.hrw.org/en/reports/2002/08/20/war-crimes-kisangani-0. Retrieved 2010-05-02.

- ^ Full text of constitution (French)

- ^ Ludwig, Arnold M. (2002). King of the Mountain: The Nature of Political Leadership. p. 72. ISBN 0813122333.

- ^ Nafziger, E. Wayne; Raimo Frances Stewart (2000). War, Hunger, and Displacement: The Origins of Humanitarian Emergencies. p. 261. ISBN 0198297394.

- ^ Mesquita, Bruce Bueno de (2003). The Logic of Political Survival. p. 167. ISBN 0262025469.

- ^ Court agrees to release Mobutu assets. Basel Institute of Governance.

- ^ Werve, Jonathan (2006). The Corruption Notebooks 2006. p. 57.

- ^ "Corruption perceptions index 2004". Transparency International.

- ^ "Corruption perceptions index 2005". Transparency International.

- ^ "Corruption perceptions index 2006". Transparency International.

- ^ "Corruption perceptions index 2007". Transparency International.

- ^ "Corruption perceptions index 2008". Transparency International.

- ^ J. Graf Lambsdorff (2006). "Corruption Perceptions Index 2006". Transparency International. http://www.transparency.org/policy_research/surveys_indices/cpi/2006. Retrieved 2008-01-21.

- ^ John Vandiver. "An April 2009 report to Congress by the National Defense Stockpile Center". Stripes.com. http://www.stripes.com/article.asp?section=104&article=69718. Retrieved 2010-11-22.

- ^ "DR Congo's $24 trillion fortune. - Free Online Library". Thefreelibrary.com. http://www.thefreelibrary.com/DR+Congo's+$24+trillion+fortune.-a0193800184. Retrieved 2011-07-22.

- ^ "Congo with $24 Trillion in Mineral Wealth BUT still Poor". News About Congo. 2009-03-15. http://www.newsaboutcongo.com/2009/03/congo-with-24-trillion-in-mineral-wealth-but-still-poor.html. Retrieved 2011-07-22.

- ^ Kuepper, Justin (2010-10-26). "Mining Companies Could See Big Profits in Congo «". Theotcinvestor.com. http://theotcinvestor.com/mining-companies-could-see-big-profits-in-congo-855/. Retrieved 2011-07-22.

- ^ Elle “pouvait se prévaloir

- ^ "Dublin". Research and Markets. http://www.researchandmarkets.com/research/e074e9/democratic_republi. Retrieved 2010-11-22.

- ^ "Cobalt: World Mine Production, By Country". http://www.indexmundi.com/en/commodities/minerals/cobalt/cobalt_t8.html. Retrieved 2008-06-30.

- ^ "DR Congo poll crucial for Africa" BBC News. 16 November 2006.

- ^ Polgreen, Lydia (16 November 2008). "Congo's Riches, Looted by Renegade Troops, NY Times, 11/15/08". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2008/11/16/world/africa/16congo.html?scp=2&sq=congo&st=nyt. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- ^ "Katanga Project Update and 2Q 2008 Financials, Katanga Mining Limited, 8/12/08". http://www.katangamining.com/kat/media/newsreleases/news2008/2008-08-12/.

- ^ John Vandiver. "DR Congo economic and strategic significance". Stripes.com. http://www.stripes.com/article.asp?section=104&article=69718. Retrieved 2010-11-22.

- ^ "World Bank Pledges $1 Billion to Democratic Republic of Congo". VOA News (Voice of America). 10 March 2007. http://www.voanews.com/english/news/a-13-2007-03-10-voa4-66771457.html. Retrieved 25 December 2008.

- ^ "OHADA.com: The business law portal in Africa". http://www.ohada.com/index.php. Retrieved 2009-03-22.

- ^ "Pygmies want UN tribunal to address cannibalism". Smh.com.au. 23 May 2003.

- ^ a b Migration en République Démocratique du Congo: Profil national 2009. International Organization for Migration. 2009. http://publications.iom.int/bookstore/index.php?main_page=product_info&cPath=41_42&products_id=592. Retrieved 2010-08-17.

- ^ "Concluding comments of the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women: Democratic Republic of the Congo" (PDF). http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/cedaw/cedaw36/cc/DRC/0647846E.pdf.

- ^ "Violence Against Women in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC)" (PDF). http://www.peacewomen.org/un/ecosoc/CEDAW/36th_session/DRC/NGO_report.pdf.

- ^ "UN expert on violence against women expresses serious concerns following visit to Democratic Republic of Congo". http://www.onug.ch/__80256edd006b9c2e.nsf/(httpNewsByYear_en)/a4f381eea9d4ab63c12573280031fbf3?OpenDocument&Click=.[dead link]

- ^ "DRC: 'Civilians bearing brunt of South Kivu violence'". http://www.irinnews.org/Report.aspx?ReportId=73033. "The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) has expressed concern over abuses against civilians, especially women and children, in South Kivu in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. It frequently receives reports of abductions, executions, rapes, and pillage."

- ^ "DRC: 'Pendulum displacement' in the Kivus". http://www.irinnews.org/Report.aspx?ReportId=73524.

- ^ Bennett, Christian (5 December 2008). "Rape in a lawless land". The Guardian (London). http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/video/2008/dec/05/congo. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- ^ "Rapes 'surge' in DR Congo". Al Jazeera. 2010-04-15. http://english.aljazeera.net/news/africa/2010/04/201041595648701631.html. Retrieved 2010-11-22.

- ^ a b c "Republique Démocratique du Congo Enquête Démographique et de Santé (EDS-RDC) 2007 [FR208]" (PDF). http://www.minisanterdc.cd/fr/documents/eds.pdf. Retrieved 2011-07-22.

- ^ "Zaire (Democratic Republic of Congo)", Adherents.com – Religion by Location. Sources quoted are CIA Factbook (1998), 'official government web site' of Democratic Republic of Congo. Retrieved 25 may 2007.

- ^ referenced by the European Christian orientalist Timothy Insoll. The Archaeology of Islam in Sub-Saharan Africa By Timothy Insoll

- ^ "2010 Human Rights Report: Democratic Republic of the Congo". 2010 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices. US Department of State. 2011. http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/hrrpt/2010/af/154340.htm. Retrieved 24 April 2011.

- ^ Harris, Dan (2009). "Children in Congo forced into exorcisms". world news. USA today. http://www.usatoday.com/news/world/2009-05-20-childwitch_N.htm. Retrieved 24 April 2011.

- ^ "Film Addresses Children's Rights in the Congo". Inter-Congolese Dialogue. Internews Network. 2006. http://www.internews.org/multimedia/video/congo/congochildren.shtm. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ^ http://www.nytimes.com/2011/04/12/health/12global.html?_r=1&partner=rss&emc=rss

- ^ "Central Intelligence Agency". Cia.gov. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2103.html. Retrieved 2011-11-05.

- ^ a b c d e f "Congo, Democratic Republic of the". 2005 Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor. Bureau of International Labor Affairs, U.S. Department of Labor (2006). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Lambertini, A Naturalist's Guide to the Tropics, excerpt". http://www.press.uchicago.edu/Misc/Chicago/468283.html. Retrieved 2008-06-30.

- ^ Clark, Jerome (1993) "Unexplained! 347 Strange Sightings, Incredible Occurrences, and Puzzling Physical Phenomena", Visible Ink Press, ISBN 0-8103-9436-7

- ^ Mackal, R. P. (1987) A Living Dinosaur? In Search of Mokele-Mbembe. E.J. Brill, ISBN 90-04-08543-2

- ^ Congo, episode 2 of 4 ("Spirits of the Forest")

- ^ "The Bushman crisis: long term solutions – international, national and local policies"[dead link]PDF (67.9 KB), WWF, 2001.

- ^ Deforestation accelerating in Central Africa, 8 June 2007

- ^ "Gorillas on Thin Ice". United Nations Environment Programme. 15 January 2009. http://www.unep.org/Documents.Multilingual/Default.asp?DocumentID=556&ArticleID=6033&l=en&t=long. Retrieved 19 May 2010.

- ^ a b Linda Vigilant (2004). "Chimpanzees". Current Biology 14 (10): R369–R371. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2004.05.006. PMID 15186757. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6VRT-4CKF2HJ-7&_user=10&_coverDate=05%2F25%2F2004&_rdoc=1&_fmt=high&_orig=search&_sort=d&_docanchor=&view=c&_acct=C000050221&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=10&md5=f28bbfa3f0610b7d3afc4aad7b522f61.

- ^ List of airlines banned within the EU – Official EC list, updated 2011-04-20, retrieved 2011-09-20

Further reading

- Clark, John F., The African Stakes of the Congo War, 2004.

- Devlin, Larry (2007). Chief of Station, Congo: A Memoir of 1960–67. New York: PublicAffairs. ISBN 9781586484057..

- Drummond, Bill and Manning, Mark, The Wild Highway, 2005.

- Edgerton, Robert, The Troubled Heart of Africa: A History of the Congo. St. Martin's Press, December 2002.

- Hochschild, Adam, King Leopold's Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror and Heroism in Colonial Africa, 1998.

- Exenberger, Andreas/Hartmann, Simon. The Dark Side of Globalization. The Vicious Cycle of Exploitation from World Market Integration: Lesson from the Congo, Working Papers in Economics and Statistics 31, University Innsbruck 2007; availability: http://eeecon.uibk.ac.at/wopec2/repec/inn/wpaper/2007-31.pdf.

- Exenberger, Andreas/Hartmann, Simon. Doomed to Disaster? Long-term Trajectories of Exploitation in the Congo, Paper to be presented at the Workshop “Colonial Extraction in the Netherlands Indies and Belgian Congo: Institutions, Institutional Change and Long Term Consequences”, Utrecht December 3-4, 2010; availability: http://vkc.library.uu.nl/vkc/seh/research/Lists/Events/Attachments/6/Paper.ExenbergerHartmann.pdf.

- Gondola, Ch. Didier, "The History of Congo", Westport: Greenwood Press, 2002.

- Joris, Lieve, translated by Waters, Liz, The Rebels' Hour, Atlantic, 2008.

- Justenhoven, Heinz-Gerhard; Ehrhart, Hans Georg. Intervention im Kongo: eine kritische Analyse der Befriedungspolitik von UN und EU. Stuttgart : Kohlhammer, 2008. (In German) ISBN 978-3-17-020781-3.

- Kingsolver, Barbara. The Poisonwood Bible HarperCollins, 1998.

- Larémont, Ricardo René, ed. 2005. Borders, nationalism and the African state. Boulder, Colorado and London: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Lemarchand, Reni and Hamilton, Lee; Burundi: Ethnic Conflict and Genocide. Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 1994.

- Mealer, Bryan: "All Things Must Fight To Live", 2008. ISBN 1-59691-345-2.

- Melvern, Linda, Conspiracy to Murder: The Rwandan Genocide and the International Community. Verso, 2004.

- Miller, Eric: "The Inability of Peacekeeping to Address the Security Dilemma", 2010. ISBN 978-3-8383-4027-2.

- Mwakikagile, Godfrey, Nyerere and Africa: End of an Era, Third Edition, New Africa Press, 2006, "Chapter Six: Congo in The Sixties: The Bleeding Heart of Africa", pp. 147 – 205, ISBN 978-0-9802534-1-2; Mwakikagile, Godfrey, Africa and America in The Sixties: A Decade That Changed The Nation and The Destiny of A Continent, First Edition, New Africa Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0-9802534-2-9.

- Nzongola-Ntalaja, Georges, The Congo from Leopold to Kabila: A People's History, 2002.

- O'Hanlon, Redmond, Congo Journey, 1996.

- O'Hanlon, Redmond, No Mercy: A Journey into the Heart of the Congo, 1998.

- Prunier, Gérard, Africa's World War: Congo, the Rwandan Genocide, and the Making of a Continental Catastrophe, 2011 (also published as From Genocide to Continental War: The Congolese Conflict and the Crisis of Contemporary Africa: The Congo Conflict and the Crisis of Contemporary Africa).

- Renton, David; Seddon, David; Zeilig, Leo. The Congo: Plunder and Resistance, 2007. ISBN 978-1-84277-485-4.

- Reyntjens, Filip, The Great African War: Congo and Regional Geopolitics, 1996–2006 , 2009.

- Rorison, Sean, Bradt Travel Guide: Congo — Democratic Republic/Republic, 2008.

- Schulz, Manfred. Entwicklungsträger in der DR Kongo: Entwicklungen in Politik, Wirtschaft, Religion, Zivilgesellschaft und Kultur, Berlin : Lit, 2008, (in German) ISBN 978-3-8258-0425-1.

- Stearns, Jason: Dancing in the Glory of Monsters: the Collapse of the Congo and the Great War of Africa, Public Affairs, 2011.

- Tayler, Jeffrey, Facing the Congo, 2001.

- Turner, Thomas, The Congo Wars: Conflict, Myth and Reality, 2007.

- Wrong, Michela, In the Footsteps of Mr. Kurtz: Living on the Brink of Disaster in Mobutu's Congo.

- Osman,Mohamed Omer Guudle(November,2011) Africa: A rich Continent where poorest people live, The Case of DR Congo and the exploitation of the World Market

External links

- Government

- General

- Country Profile from the BBC News

- Democratic Republic of the Congo entry at The World Factbook

- Democratic Republic of the Congo from UCB Libraries GovPubs

- Democratic Republic of the Congo at the Open Directory Project

- Wikimedia Atlas of Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Democratic Republic of Congo at WorldWikia

- Crisis briefing on Congo from Reuters AlertNet

- Humanitarian information coverage on ReliefWeb

- The Democratic Republic of Congo from Global Issues

- Tourism

- Democratic Republic of the Congo travel guide from Wikitravel

- Official Website of Virunga National Park

- Documentaries

- News coverage of the conflict

- BBC DR Congo: Key facts

- BBC Q&A: DR Congo conflict

- BBC Timeline: Democratic Republic of Congo

- BBC In pictures: Congo crisis

- "Rape of a Nation" by Marcus Bleasdale (VII) on MediaStorm

- Maps of Congo before and after independence

- Other

Categories:- Democratic Republic of the Congo

- African countries

- Bantu countries and territories

- Countries bordering the Atlantic Ocean

- French-speaking countries

- Member states of La Francophonie

- Member states of the African Union

- Least developed countries

- Republics

- Swahili-speaking countries and territories

- Member states of the United Nations

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.