- Kazimir Malevich

-

Kazimir Malevich

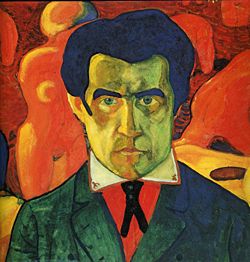

Self-Portrait, 1912Birth name Kazimir Severinovich Malevich Born 23 February 1879

Kiev Governorate of Russian Empire, now UkraineDied 15 May 1935 (aged 56)

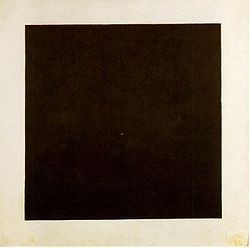

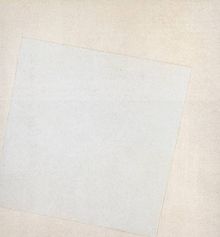

Leningrad, Soviet UnionNationality Ethnic Pole in the Russian Empire, and later, the Soviet Union Field Painting Training Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture Movement Suprematism Works Black Square, 1915; White on White, 1918 Kazimir Severinovich Malevich (Russian: Казимир Северинович Малевич [kɐzʲɪˈmʲir sʲɪvʲɪˈrʲinəvʲɪt͡ɕ mɐˈlʲevʲɪt͡ɕ], Polish: Kazimierz Malewicz, Ukrainian: Казимир Северинович Малевич [kazɪˈmɪr sɛwɛˈrɪnɔwɪtʃ mɑˈlɛwɪtʃ], German: Kasimir Malewitsch, (February 23, 1879, previously 1878: see below – May 15, 1935) was a Russian painter and art theoretician, born of ethnic Polish parents. He was a pioneer of geometric abstract art and the originator of the Avant-garde Suprematist movement.

Contents

Early life

Kazimir Malevich was born near Kiev in the Kiev Governorate of the Russian Empire. His parents, Seweryn and Ludwika Malewicz, were ethnic Poles,[1] and he was baptised in the Roman Catholic Church. His father managed a sugar factory. Kazimir was the first of 14 children, only nine of which survived into adulthood. His family moved often and he spent most of his childhood in the villages of Ukraine amidst sugar-beet plantations, far from centers of culture. Until age 12 he knew nothing of professional artists, though art had surrounded him in childhood. He delighted in peasant embroidery, and in decorated walls and stoves. He himself was able to paint in the peasant style. He studied drawing in Kiev from 1895 to 1896.

Birth date

Recently Ukrainian art historians established the precise birthdate of the artist: February 23, 1879. Professor D. Gorbachev, in his 2006 book Malevich and Ukraine, (published in Kiev) reveals many new biographical details. French art historian Andrei Nakov re-established Malevich's birth year as 1879 (and not 1878), and argues for restoration of the Polish spelling of his name.

Work

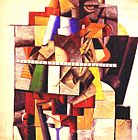

From 1896 to 1904 Kazimir Malevich lived in Kursk. In 1904, after the death of his father, he moved to Moscow. He studied at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture from 1904 to 1910 and in the studio of Fedor Rerberg in Moscow (1904 to 1910). In 1911 he participated in the second exhibition of the group Soyuz Molodyozhi (Union of Youth) in St. Petersburg, together with Vladimir Tatlin and, in 1912, the group held its third exhibition, which included works by Aleksandra Ekster, Tatlin and others. In the same year he participated in an exhibition by the collective Donkey's Tail in Moscow. By that time his works were influenced by Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov, Russian avant-garde painters who were particularly interested in Russian folk art called lubok. In March 1913 a major exhibition of Aristarkh Lentulov's paintings opened in Moscow. The effect of this exhibition was comparable with that of Paul Cézanne in Paris in 1907, as all the main Russian avant-garde artists of the time (including Malevich) immediately absorbed the cubist principles and began using them in their works. Already in the same year the Cubo-Futurist opera Victory Over the Sun with Malevich's stage-set became a great success. In 1914 Malevich exhibited his works in the Salon des Independants in Paris together with Alexander Archipenko, Sonia Delaunay, Aleksandra Ekster and Vadim Meller, among others.

Suprematism

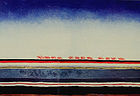

In 1915, Malevich laid down the foundations of Suprematism when he published his manifesto From Cubism to Suprematism. In 1915–1916 he worked with other Suprematist artists in a peasant/artisan co-operative in Skoptsi and Verbovka village. In 1916–1917 he participated in exhibitions of the Jack of Diamonds group in Moscow together with Nathan Altman, David Burliuk and A. Ekster, among others. Famous examples of his Suprematist works include Black Square (1915)[2] and White on White (1918).

In 1918, Malevich decorated a play, Mystery Bouffe, by Vladimir Mayakovskiy produced by Vsevolod Meyerhold.

He was also interested in aerial photography and aviation, which led him to abstractions inspired by or derived from aerial landscapes. As Professor Julia Bekman Chadaga (now of Macalaster College [1]) writes:

In his later writings, Malevich defined the "additional element" as the quality of any new visual environment bringing about a change in perception... In a series of diagrams illustrating the "environments" that influence various painterly styles, the Suprematist is associated with a series of aerial views rendering the familiar landscape into an abstraction... (excerpted from Ms. Bekman Chadaga's paper delivered at Columbia University's 2000 symposium, "Art, Technology, and Modernity in Russia and Eastern Europe")

Photograph of Malevich

Photograph of Malevich

Post-revolution

After the October Revolution, Malevich became a member of the Collegium on the Arts of Narkompros, the Commission for the Protection of Monuments and the Museums Commission (all from 1918–1919). He taught at the Vitebsk Practical Art School in the USSR (now part of Belarus) (1919–1922), the Leningrad Academy of Arts (1922–1927), the Kiev State Art Institute (1927–1929), and the House of the Arts in Leningrad (1930). He wrote the book The World as Non-Objectivity published in Munich 1926, only translated into English in 1959. In it he outlines his Suprematist theories.

In 1923, Malevich was appointed director of Petrograd State Institute of Artistic Culture, which was forced to close in 1926 after a Communist party newspaper called it "a government-supported monastery" rife with "counterrevolutionary sermonizing and artistic debauchery." The Soviet state was by then heavily promoting a politically sustainable style of art called Social Realism — a style Malevich had spent his entire career repudiating. Nevertheless, he swam with the current, and was quietly tolerated by the Communists.[3]

International recognition and banning

In 1927, he travelled to Warsaw and then to Berlin and Munich for a retrospective which finally brought him international recognition. He arranged to leave most of the paintings behind when he returned to the Soviet Union. Malevich's assumption that a shifting in the attitudes of the Soviet authorities towards the modernist art movement would take place after the death of Lenin and Trotsky's fall from power, was proven correct in a couple of years, when the Stalinist regime turned against forms of abstraction, considering them a type of "bourgeois" art, that could not express social realities. As a consequence, many of his works were confiscated and he was banned from creating and exhibiting similar art.

Critics derided Malevich for reaching art by negating everything good and pure: love of life and love of nature. The Westernizer artist and art historian Alexandre Benois was one such critic. Malevich responded that art can advance and develop for art's sake alone, regardless of its pleasure saying that "art does not need us, and it never did".

Malevich's work only recently reappeared in art exhibitions in Russia after a long absence. Since then art followers have labored to reintroduce the artist to Russian lovers of painting. A book of his theoretical works with an anthology of reminiscences and writings has been published.

Death

Malevich died of cancer in Leningrad on May 15, 1935. On his deathbed he was exhibited with the black square above him, and mourners at his funeral rally were permitted to wave a banner bearing a black square.[3] His ashes were sent to Nemchinovka, and buried in a field near his dacha. A white cube decorated with a black square was placed on his tomb. The city of Leningrad bestowed a pension on Malevich's mother and daughter. "No phenomenon is mortal," Malevich wrote in an unpublished manuscript, "and this means not only the body but the idea as well, a symbol that one is eternally reincarnated in another form which actually exists in the conscious and unconscious person."

Posthumous sales

Self-portrait, 1933 (detail)

Self-portrait, 1933 (detail)

Black Square, the fourth version of his magnum opus painted in the 1920s was discovered in 1993 in Samara and purchased by Inkombank for $250,000.[4] In April 2002 the painting was auctioned for an equivalent of one million dollars. The purchase was financed by the Russian philanthropist Vladimir Potanin, who donated funds to Russian Ministry of Culture[5] and ultimately to State Hermitage Museum collection.[4] According to the Hermitage website, this was the largest private contribution to state art museums since the October Revolution.[5]

On November 3, 2008 a work by Malevich entitled Suprematist Composition from 1916 set the world record for any Russian work of art and any work sold at auction for that year, selling at Sotheby’s in New York City for just over $60 million U.S. (far surpassing his previous record of $17 million set in 2000).

He was awarded the highest category "1A - a world famous artist" in "United Artists Rating".

Malevich in popular culture

Malevich life inspires many references featuring events and the paintings themselves as players. The smuggling of Malevich paintings out of Russia is a key to the plot line of writer Martin Cruz Smith's thriller Red Square. Noah Charney's novel, The Art Thief tells the story of two stolen Malevich White on White paintings, and discusses the implications of Malevich's radical Suprematist compositions on the art world. British artist Keith Coventry has used Malevich's paintings to make comments on modernism, in particular his Estate Paintings. Malevich's work is also featured prominently in the Lars Von Trier film Melancholia.

Selected works

- 1912 Morning in the Country after Snowstorm

- 1912 The Woodcutter

- 1912-13 Reaper on Red Background

- 1914 The Aviator

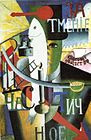

- 1914 An Englishman in Moscow

- 1914 Soldier of the First Division

- 1915 Black Square and Red Square

- 1915 Red Square: Painterly Realism of a Peasant Woman in Two Dimensions

- 1915 Suprematist Composition

- 1915 Suprematism (1915)

- 1915 Suprematist Painting: Aeroplane Flying

- 1915 Suprematism: Self-Portrait in Two Dimensions

- 1915-16 Suprematist Painting (Ludwigshafen)

- 1916 Suprematist Painting (1916)

- 1916 Supremus No. 56

- 1916-17 Suprematism (1916–17)

- 1917 Suprematist Painting (1917)

- 1928-32 Complex Presentiment: Half-Figure in a Yellow Shirt

- 1932-34 Running Man

Gallery

-

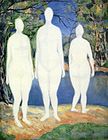

Suprematism, Museum of Art, Krasnodar 1916

See also

- Aerial landscape art

- El Lissitzky

- IRWIN

- Lyubov Popova

- OBERIU

- Rabo Karabekian

- Suprematism

- Supremus

- Suprematist Composition

- UNOVIS

Notes

- ^ Milner and Malevich 1966, p. x.

- ^ Drutt and Malevich 2003, p. 243.

- ^ a b Journal of the American Medical Association, Volume 305, Number 11 (March 16, 2011), p. 1066.

- ^ a b Sophia Kishkovsky (July 18, 2002). "From a Crate of Potatoes, a Noteworthy Gift Emerges". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2002/07/18/arts/arts-abroad-from-a-crate-of-potatoes-a-noteworthy-gift-emerges.html. Retrieved 2009-08-23.

- ^ a b "Co-operation With the State Hermitage Museum". State Hermitage Museum. http://www.hermitagemuseum.org/html_En/05/hm5_4_0.html. Retrieved 2009-08-23.

References

- Andrei Nakov Kasimir Malevich, Catalogue raisonné, Paris, Adam Biro, 2002

- Andrei Nakov vol. IV of Kasimir Malevich, le peintre absolu, Paris, Thalia Édition, 2007

- The Non-objective World, Kasimir Malevich, trans. Howard Dearstyne, Paul Theobald, 1959. ISBN 0486429741

- Kazimir Malevich and Suprematism 1878-1935, Gilles Néret, Taschen, 2003. ISBN 0874141192

- Dreikausen, Margret, "Aerial Perception: The Earth as Seen from Aircraft and Spacecraft and Its Influence on Contemporary Art" (Associated University Presses: Cranbury, NJ; London, England; Mississauga, Ontario: 1985). ISBN 0-87982-040-3

- Drutt, Matthew; Malevich, Kazimir, Kazimir Malevich: suprematism, Guggenheim Museum, 2003, ISBN 0892072652

- Milner, John; Malevich, Kazimir, Kazimir Malevich and the art of geometry, Yale University Press, 1996. ISBN 0300064179

- Shishanov V.A. Vitebsk Museum of Modern Art: a history of creation and a collection. 1918–1941. - Minsk: Medisont, 2007. - 144 p.Mylivepage.ru

- Kazimir Malevich in the State Russian Museum. Palace Editions. ISBN 978-3930775767. (English Edition)

- Malevich and his Influence, Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein, 2008. ISBN 978-3-7757-1877-6

- Ivanov, Sergei."Unknown Socialist Realism. The Leningrad School". Saint Petersburg: NP-Print, 2007, ISBN13 9785901724217

External links and references

- All Paintings of Kazimir Malevich

- Andrei Nakov's works on Kazimir Malevich

- Guggenheim: Kazimir Malevich

- "White on White"

- DA Collection

- Kazimir-Malevich.org - 128 works by Kazimir Malevich

- "Victory Over the Sun" discussed

- Das schwarze quadrat (The Black Square) - Exhibition at Kunsthalle Hamburg

- Lawsuit over ownership of Malevich's Paintings Settled

- Less known paintings and photographs from private collection

- Sergei V. Ivanov. The Leningrad School of painting. Historical outline

- Kazimir Malevich Website

People from Russia Leaders and religious - Pre-1168

- 1168–1917

- 1922–1991

- 1991–present

- RSFSR leaders

- General secretaries

- Soviet premiers (1st deputies)

- Soviet heads of state (and their spouses)

- Prime ministers (1st deputies)

- Foreign ministers

- Prosecutors general

- Metropolitans and patriarchs

- Saints

Military and explorers - Field marshals

- Soviet marshals

- Admirals

- Aviators

- Cosmonauts

Scientists and inventors - Aerospace engineers

- Astronomers and astrophysicists

- Biologists

- Chemists

- Earth scientists

- Electrical engineers

- IT developers

- Linguists and philologists

- Mathematicians

- Naval engineers

- Physicians and psychologists

- Physicists

- Weaponry makers

Artists and writers Sportspeople Chess playersPainters of the Leningrad Union of Artists of 1932-1991 Piotr Alberti · Nathan Altman · Evgenia Antipova · Taisia Afonina · Vsevolod Bazhenov · Irina Baldina · Nikolai Baskakov · Yuri Belov · Piotr Belousov · Zlata Bizova · Olga Bogaevskaya · Veniamin Borisov · Isaak Brodsky · Piotr Buchkin · Vladimir Chekalov · Evgeny Chuprun · Irina Dobrekova · Alexei Eriomin · Pavel Filonov · Rudolf Frentz · Sergei Frolov · Nikolai Galakhov · Irina Getmanskaya · Vasily Golubev · Vladimir Gorb · Tatiana Gorb · Elena Gorokhova · Abram Grushko · Mikhail Kaneev · Yuri Khukhrov · Tatiana Kopnina · Maya Kopitseva · Boris Korneev · Alexander Koroviakov · Elena Kostenko · Gevork Kotiantz · Vladimir Krantz · Yaroslav Krestovsky · Mikhail Kozell · Engels Kozlov · Marina Kozlovskaya · Aleksandr Laktionov · Valeria Larina · Boris Lavrenko · Ivan Lavsky · Oleg Lomakin · Dmitry Maevsky · Kazimir Malevich · Gavriil Malish · Evsey Moiseenko · Valentina Monakhova · Alexei Mozhaev · Nikolai Mukho · Mikhail Natarevich · Alexander Naumov · Piotr Nazarov · Vera Nazina · Anatoli Nenartovich · Samuil Nevelshtein · Yuri Neprintsev · Dmitry Oboznenko · Lev Orekhov · Sergei Osipov · Victor Otiev · Vladimir Ovchinnikov · Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin · Nikolai Pozdneev · Evgeny Pozdnekov · Alexander Pushnin · Maria Rudnitskaya · Galina Rumiantseva · Kapitolina Rumiantseva · Lev Russov · Arcady Rylov · Ivan Savenko · Alexander Savinov · Gleb Savinov · Vladimir Sakson · Alexander Samokhvalov · Vladimir Seleznev · Arseny Semionov · Alexander Semionov · Yuri Shablikin · Boris Shamanov · Alexander Shmidt · Nadezhda Shteinmiller · Elena Skuin · Galina Smirnova · Alexander Sokolov · Alexander Stolbov · Alexander Tatarenko · German Tatarinov · Victor Teterin · Nikolai Timkov · Leonid Tkachenko · Mikhail Tkachev · Mikhail Trufanov · Vitaly Tulenev · Yuri Tulin · Boris Ugarov · Ivan Varichev · Anatoli Vasiliev · Piotr Vasiliev · Valery Vatenin · Nina Veselova · Igor Veselkin · Rostislav Vovkushevsky · Lazar Yazgur · Vecheslav Zagonek · Ruben Zakharian · Sergei Zakharov · Maria Zubreeva

Years in the History of Fine Arts of the USSR 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | 1934 | 1935 | 1936 | 1937 | 1938 | 1939 | 1940 | 1941 | 1942 | 1943 | 1944 | 1945 | 1946 | 1947 | 1948 | 1949 | 1950 | 1951 | 1952 | 1953 | 1954 | 1955 | 1956 | 1957 | 1958 | 1959 | 1960 | 1961 | 1962 | 1963 | 1964 | 1965 | 1966 | 1967 | 1968 | 1969 | 1970 | 1971 | 1972 | 1973 | 1974 | 1975 | 1976 | 1977 | 1978 | 1979 | 1980 | 1981 | 1982 | 1983 | 1984 | 1985 | 1986 | 1987 | 1988 | 1989 | 1990 | 1991

Categories:- 19th-century painters

- 20th-century painters

- Cancer deaths in Russia

- Futurist painters

- Imperial Russian ethnic Polish people

- Imperial Russian painters

- Modern painters

- People from Kiev

- Polish artists

- Polish painters

- Russian avant-garde

- Painters from Saint Petersburg

- Soviet artists

- Soviet painters

- Ukrainian artists

- Ukrainian ethnic Polish people

- Ukrainian painters

- 1879 births

- 1935 deaths

- Ukrainian avant-garde

- Deaths from prostate cancer

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.