- October Revolution

-

This article is about the Soviet Revolution of 1917. For other uses, see October Revolution (disambiguation).

October Revolution Part of the Russian Revolution of 1917, Revolutions of 1917–23 and the Russian Civil War

Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets, which took power in the October RevolutionDate 7–8 November 1917 Location Petrograd, Russia Result Bolshevik victory - Creation of Soviet Russia

- End of Russian Provisional Government, Russian Republic and dual power

- Start of the Russian Civil War

Belligerents  Bolshevik Party

Bolshevik Party

Left SRs

Left SRs

Red Guards

Red Guards

2nd All-Russian Congress of Soviets

2nd All-Russian Congress of Soviets

Petrograd Soviet

Petrograd Soviet Russian Soviet Republic (from November 7)

Russian Soviet Republic (from November 7)

Russian Republic (to November 7)

Russian Republic (to November 7)

Russian Provisional Government (to November 8)

Russian Provisional Government (to November 8)Commanders and leaders  Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Lenin

Leon Trotsky

Leon Trotsky

Pavel Dybenko

Pavel Dybenko Alexander Kerensky

Alexander KerenskyStrength 10,000 red sailors, 20,000-30,000 red guard soldiers 500-1,000 volunteer soldiers, 1,000 soldiers of women's battalion Casualties and losses Few wounded red guard soldiers All deserted - October Revolution

- Southern Front

- Eastern Front

- Northern Front

- Ukraine

- Finland

- Finnic peoples

- Estonia

- Latvia

- Lithuania

- Ukraine

- Poland

- Georgia

- Armenia and Azerbaijan

- Left-wing uprisings against the Bolsheviks

- Tambov

- Basmachi

- Yakutia

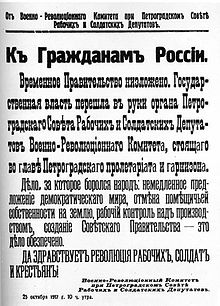

The October Revolution (Russian: Октябрьская революция, Oktyabr'skaya revolyutsiya), also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (Russian: Великая Октябрьская социалистическая революция, Velikaya Oktyabr'skaya sotsialisticheskaya revolyutsiya), Red October, the October Uprising or the Bolshevik Revolution, was a political revolution and a part of the Russian Revolution of 1917. It took place with an armed insurrection in Petrograd traditionally dated to 25 October 1917 Old Style Julian Calendar (O.S.), which corresponds with 7 November 1917 New Style (N.S.). Gregorian Calendar.

It followed and capitalized on the February Revolution of the same year. The October Revolution in Petrograd overthrew the Russian Provisional Government and gave the power to the local soviets dominated by Bolsheviks. As the revolution was not universally recognized outside of Petrograd there followed the struggles of the Russian Civil War (1917–1922) and the creation of the Soviet Union in 1922.

The revolution was led by the Bolsheviks, who used their influence in the Petrograd Soviet to organize the armed forces. Bolshevik Red Guards forces under the Military Revolutionary Committee began the takeover of government buildings on 24 October 1917 (O.S.). The following day, the Winter Palace (the seat of the Provisional government located in Petrograd, then capital of Russia), was captured.

Contents

Etymology

Initially, the event was referred as the October coup (Октябрьский переворот) or the Uprising of 25th, as seen in contemporary documents (for example, in the first editions of Lenin's complete works). With time, the term October Revolution came into use. It is also known as the "November Revolution" having occurred in November according to the Gregorian Calendar.

The Great October Socialist Revolution (Russian: Великая Октябрьская Социалистическая Революция, Velikaya Oktyabr'skaya sotsialisticheskaya revolyutsiya) was the official name for the October Revolution in the Soviet Union after the 10th anniversary of the Revolution in 1927.

Background

Nationwide crisis had developed in Russia affecting social, economic, and political relations. Disorder in industry and transport had intensified, and difficulties in obtaining provisions had increased. Gross industrial production in 1917 had decreased by over 36 percent from what it had been in 1916. In the autumn, as much as 50 percent of all enterprises were closed down in the Urals, the Donbas, and other industrial centers, leading to mass unemployment. At the same time, the cost of living increased sharply. The real wages of the workers fell about 50 percent from what they had been in 1913. Russia's national debt in October 1917 had risen to 50 billion rubles. Of this, debts to foreign governments constituted more than 11 billion rubles. The country faced the threat of financial bankruptcy.

In September and October 1917, there were strikes by the Moscow and Petrograd workers, the miners of the Donbas, the metalworkers of the Urals, the oil workers of Baku, the textile workers of the Central Industrial Region, and the railroad workers on 44 different railway lines. In these months alone more than a million workers took part in mass strike action. Workers established control over production and distribution in many factories and plants in a social revolution.[1]

By October 1917 there had been over four thousand peasant uprisings against landowners. When the Provisional Government sent out punitive detachments it only enraged the peasants. The garrisons in Petrograd, Moscow, and other cities, the Northern and Western fronts, and the sailors of the Baltic Fleet in September openly declared through their elected representative body Tsentrobalt that they did not recognize the authority of the Provisional Government and would not carry out any of its commands.[2]

In a diplomatic note of the 1 May, the minister of foreign affairs, Pavel Milyukov, expressed the Provisional Government's desire to carry the war against the Central Powers through "to a victorious conclusion", arousing broad indignation. On 1–4 May about 100,000 workers and soldiers of Petrograd, and after them the workers and soldiers of other cities, led by the Bolsheviks, demonstrated under banners reading "Down with the war!" and "all power to the soviets!" The mass demonstrations resulted in a crisis for the Provisional Government.[2]

1 July saw more demonstrations, as about 500,000 workers and soldiers in Petrograd demonstrated, again demanding "all power to the soviets", "down with the war", and "down with the ten capitalist ministers". The Provisional Government opened an offensive against them on 1 July but it soon collapsed. The news of the offensive and its collapse intensified the struggle of the workers and the soldiers. A new crisis in the Provisional Government began on 15 July.

On 16 July spontaneous demonstrations of workers and soldiers began in Petrograd, demanding that power be turned over to the soviets. The Central Committee of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party provided leadership to the spontaneous movements. On 17 July, over 500,000 people participated in a peaceful demonstration in Petrograd, the so-called July Days. The Provisional Government, with the support of the Socialist-Revolutionary Party-Menshevik leaders of the All-Russian Executive Committee of the Soviets, ordered an armed attack against the demonstrators. Fifty-six people were killed and 650 were wounded.[2]

A period of repression followed. On 5–6 July attacks were made on the editorial offices and printing presses of Pravda and on the Palace of Kshesinskaia, where the Central Committee and the Petrograd Committee of the Bolsheviks were located. On 7 July a government decree ordering the arrest and trial of Vladimir Lenin was published. He was forced to go underground, just as he had been under the Tsarist regime. Bolsheviks began to be arrested, workers were disarmed, and revolutionary military units in Petrograd were disbanded or sent off to the front. On 12 July the Provisional Government published a law introducing the death penalty at the front. The formation of the second coalition government, with Alexander Kerensky as chairman, was completed on 24 July.[2]

Another problem for the government centered around General Lavr Kornilov, who had been Commander-in-Chief since 18 July. In response to a Bolshevik appeal, Moscow’s working class began a protest strike of 400,000 workers. The Moscow workers were supported by strikes and protest rallies by workers in Kiev, Kharkov, Nizhny Novgorod, Ekaterinburg, and other cities.

In what became known as the Kornilov Affair, Kornilov directed an army under Aleksandr Krymov to march toward Petrograd with Kerensky's agreement.[3] Although the details remain sketchy, Kerensky appeared to become frightened by the possibility of a coup and the order was countermanded (historian Richard Pipes is quite adamant that the whole episode was engineered by Kerensky himself[4]). On 27 August, feeling betrayed by the Kerensky government who had previously agreed with his views on how to restore order to Russia, Kornilov pushed on towards Petrograd. With few troops to spare on the front, Kerensky was forced to turn to the Petrograd Soviet for help. Bolsheviks, Mensheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries confronted the army and convinced them to stand down.[5] The damage was already done, however. Right-wingers felt betrayed, and the left wing was resurgent.

With Kornilov defeated, the Bolsheviks' popularity with the soviets significantly increased. During and after the defeat of Kornilov a mass turn of the soviets toward the Bolsheviks began, both in the central and local areas. On 31 August the Petrograd Soviet of Workers and Soldiers Deputies and on 5 September the Moscow Soviet Workers Deputies adopted the Bolshevik resolutions on the question of power. The Bolsheviks won a majority in the Soviets of Briansk, Samara, Saratov, Tsaritsyn, Minsk, Kiev, Tashkent, and other cities. In one day alone, 1 September, the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of Soviets received demands from 126 local soviets urging it to take power into its own hands.[2]

Events

On 23 October [O.S. 10 October] 1917, the Bolsheviks' Central Committee voted 10-2 for a resolution saying that "an armed uprising is inevitable, and that the time for it is fully ripe".[6][dubious ]

On 5 November [O.S. 23 October] 1917, Bolshevik leader Jaan Anvelt led his leftist revolutionaries in an uprising in Tallinn, the capital of the Autonomous Governorate of Estonia.[citation needed] Two days later, Bolsheviks led their forces in the uprising in Petrograd (modern day Saint Petersburg), the capital of Russia, against the Kerensky Provisional Government. For the most part, the revolt in Petrograd was bloodless, with the Red Guards led by Bolsheviks taking over major government facilities with little opposition before finally launching an assault on the poorly defended Winter Palace.[7]

The official Soviet version of events follows: An assault led by Vladmir Lenin was launched at 9:45 p.m. signaled by a blank shot from the cruiser Aurora. (The Aurora was placed in Petrograd and still stands there now.) The Winter Palace was guarded by Cossacks, cadets (military students), and a Women's Battalion. It was taken at about 2 a.m. The earlier date was made the official date of the Revolution, when all offices except the Winter Palace had been taken. More contemporary research with access to government archives significantly corrects accepted Soviet edited and embellished history. The archival version shows that parties of Bolshevik operatives sent out from the Smolny by Lenin took over all critical centers of power in Petrograd in the early hours of the night without a shot being fired. In actual fact the effectively unoccupied Winter Palace also was taken bloodlessly by a small group which broke in, got lost in the cavernous interior, and accidentally happened upon the remnants of Kerensky's provisional government in the imperial family's breakfast room. The illiterate revolutionaries then compelled those arrested to write up their own arrest papers. The stories of the "defense of the Winter Palace" and the heroic "Storming of the Winter Palace" came later as the creative propaganda product of Bolshevik publicists. Grandiose paintings depicting the "Women's Battalion" and photo stills taken from Sergei Eisenstein's staged film depicting the "politically correct" version of the October events in Petrograd came to be taken as truth.[8]

Later official accounts of the revolution from the Soviet Union would depict the events in October as being far more dramatic than they actually had been. (See firsthand account by British General Knox.) This was helped by the historical reenactment, entitled The Storming of the Winter Palace, which was staged in 1920. This reenactment, watched by 100,000 spectators, provided the model for official films made much later, which showed a huge storming of the Winter Palace and fierce fighting (See Sergei Eisenstein's October: Ten Days That Shook the World).[citation needed] In reality the Bolshevik insurgents faced little or no opposition.[7] The insurrection was timed and organized to hand state power to the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies, which began on 25 October. After a single day of revolution eighteen people had been arrested and two had been killed.

The Spread of Soviet Power (Gregorian calendar)

7/11/1917: Petrograd, Minsk, Novgorod and Ivanovo-Voznesensk. 8/11/1917: Ufa, Kazan, Revel and Yekaterinburg. 9/11/1917: Vitebsk, Yaroslavl, Saratov, Samara and Izhevsk. 10/11/1917: Rostov, Tver and Nizhny Novgorod. 12/11/1917: Voronezh, Smolensk and Gomel. 13/11/1917: Tambov. 14/11/1917: Orel and Perm. 15/11/1917: Pskov, Moscow and Baku. 27/11/1917: Tsaritsyn 1/12/1917: Mogilev. 8/12/1917: Vyatka. 10/12/1917: Kishinev 11/12/1917: Kaluga. 14/12/1917: Novorossisk. 15/12/1917: Kostroma 20/12/1917: Tula. 24/12/1917: Kharkov. 29/12/1917: Sebastopol. 4/1/1918: Penza. 11/1/1917: Yekaterinoslav. 17/1/1918: Petrozavodsk. 19/1/1918: Poltava. 22/1/1918: Zhitomir. 26/1/1918: Simferopol. 27/1/1918: Nikolayev. 28/1/1918: Helsinki. 31/1/1918: Odessa and Orenburg. 7/2/1918: Astrakhan. 8/2/1918: Kiev and Vologda. 17/2/1918: Archangel. 25/2/1918: Novocherkassk.

Outcomes

The Second Congress of Soviets consisted of 670 elected delegates; 300 were Bolshevik and nearly a hundred were Left Socialist-Revolutionaries, who also supported the overthrow of the Alexander Kerensky Government.[9] When the fall of the Winter Palace was announced, the Congress adopted a decree transferring power to the Soviets of Workers', Soldiers' and Peasants' Deputies, thus ratifying the Revolution.

The transfer of power was not without disagreement. The center and Right wings of the Socialist Revolutionaries as well as the Mensheviks believed that Lenin and the Bolsheviks had illegally seized power and they walked out before the resolution was passed. As they exited, they were taunted by Leon Trotsky who told them "You are pitiful isolated individuals; you are bankrupts; your role is played out. Go where you belong from now on — into the dustbin of history!"[10]

The following day, the Congress elected a Council of People's Commissars (Sovnarkom) as the basis of a new Soviet Government, pending the convocation of a Constituent Assembly, and passed the Decree on Peace and the Decree on Land. This new government was also officially called "provisional" until the Assembly was dissolved.

The Council of People's Commissars now began to arrest the leaders of opposition parties. Dozens of Constitutional Democratic Party (Kadet) leaders and members of the Constituent Assembly were imprisoned in The Peter and Paul Fortress. These were to be followed by the arrests of Socialist-Revolutionary Party and Menshevik leaders. On 20 December 1917 the Cheka was created by the decree of Vladimir Lenin.[11] These were the beginnings of the Bolshevik's consolidation of power over their political opponents.

The Decree on Land ratified the actions of the peasants who throughout Russia seized private land and redistributed it among themselves. The Bolsheviks viewed themselves as representing an alliance of workers and peasants and memorialized that understanding with the Hammer and Sickle on the flag and coat of arms of the Soviet Union.

Other decrees:

- All Russian banks were nationalized.

- Private bank accounts were confiscated.

- The Church's properties (including bank accounts) were seized.

- All foreign debts were repudiated.

- Control of the factories was given to the soviets.

- Wages were fixed at higher rates than during the war, and a shorter, eight-hour working day was introduced.

Bolshevik-led attempts to seize power in other parts of the Russian Empire were largely successful in Russia proper — although the fighting in Moscow lasted for two weeks — but they were less successful in ethnically non-Russian parts of the Empire, which had been clamoring for independence since the February Revolution. For example, the Ukrainian Rada, which had declared autonomy on 23 June 1917, created the Ukrainian People's Republic on 20 November, which was supported by the Ukrainian Congress of Soviets.

This led to an armed conflict with the Bolshevik government in Petrograd and, eventually, a Ukrainian declaration of independence from Russia on 25 January 1918.[12] In Estonia, two rival governments emerged: the Estonian Provincial Assembly proclaimed itself the supreme legal authority of Estonia on 28 November 1917 and issued the Declaration of Independence on 24 February 1918, while an Estonian Bolshevik sympathizer, Jaan Anvelt, was recognized by Lenin's government as Estonia's leader on 8 December, although forces loyal to Anvelt controlled only the capital.[13]

The success of the October Revolution transformed the Russian state from parliamentarian to socialist in character. A coalition of anti-Bolshevik groups attempted to unseat the new government in the Russian Civil War from 1918 to 1922. "It was this revolution which caused a chain reaction leading to communist governance of Russia," claimed historian Edward Skinner (1951).

In an attempt to intervene in the civil war after the Bolshevik's separate peace with the Central Powers, the Allied powers (United Kingdom, France, United States and Japan) occupied parts of the Soviet Union for over two years before finally withdrawing[citation needed]. The United States did not recognize the new Russian government until 1933. The European powers recognized the Soviet Union in the early 1920s and began to engage in business with it after the New Economic Policy (NEP) was implemented.

Boris Gudz, the last survivor of the revolution, died in December 2006 at the age of 104.[14] Another witness of revolution was Boris Yefimov who died in 2008.

Historiography

Few events in historical research have been as conditioned by political influences as the October Revolution.[15] The historiography of the Revolution generally divides into three camps: the Soviet-Marxist view, the Western-Totalitarian view, and the Revisionist view.[16]

Soviet Historiography: The Marxist View

Soviet historiography of the October Revolution is intertwined with Soviet historical development. Many of the initial Soviet interpreters of the Revolution were themselves Bolshevik revolutionaries.[17] (For example, the revolutionary Leon Trotsky wrote a major narrative of the October Revolution.)[18] After the initial wave of revolutionary narratives, Soviet historians worked within “narrow guidelines” defined by the Soviet government. The rigidity of interpretive possibilities reached its height under Stalin.[19]

Soviet historians of the October Revolution interpreted the Revolution so as to establish the legitimacy of Marxist ideology, and also the Bolshevik regime. To establish the accuracy of Marxist ideology, Soviet historians generally described the Revolution as the product of class struggle. They maintained that the Revolution was the supreme event in a world history governed by historical laws. The Bolshevik Party is placed at the center of the Revolution, exposing the errors of both the moderate Provisional Government and the spurious “socialist” Mensheviks in the Petrograd Soviet. Guided by Vladimir Lenin’s leadership and his firm grasp of scientific Marxist theory, the Party led the “logically predetermined” events of the October Revolution from beginning to end. The events were, according to these historians, logically predetermined because of the socio-economic development of Russia, where the monopoly industrial capitalism alienated the masses. In this view, the Bolshevik party took the leading role in organizing these alienated industrial workers, and thereby established the construction of the first socialist state.[20]

Although Soviet historiography of the October Revolution stayed relatively constant until 1991, it did undergo some changes. Following Stalin’s death, historians (like E.N. Burdzhalov and P.V. Volobuev) published historical research that deviated significantly from the party line in refining the doctrine that the Bolshevik victory “was predetermined by the state of Russia’s socio-economic development.”[21] These historians, who comprised the “New Directions Group,” posited that the complex nature of the October Revolution “could only be explained by a multi-causal analysis, not by recourse to the mono-causality of monopoly capitalism.”[22] For them, the central actor is still the Bolshevik party, but this party triumphed “because it alone could solve the preponderance of ‘general democratic’ tasks the country faced” (such as the struggle for peace, the exploitation of landlords, and so on.)[23]

During the late Soviet period, the opening of select Soviet archives during glasnost sparked innovative research that broke away from some aspects of Marxism-Leninism, though the key features of the orthodox Soviet view remained intact.[24]

Western Historiography: the Totalitarian View

During the Cold War, Western historiography of the October Revolution developed in direct response to the assertions of the Soviet view. The Soviet Marxist-Leninist version of the October Revolution conditioned historical interpretations in the U.S. and the West. As a result, these Western historians exposed what they considered flaws in the Soviet view, thereby undermining the Bolshevik’s original legitimacy, as well as the precepts of Marxism.[25]

Far from being inevitable according the historical laws of Marxism, these Western historians presented the revolution as the result of a chain of contingent accidents. Examples of these accidental and contingent factors that precipitated the Revolution include World War I’s timing, chance, and the poor leadership of Tsar Nicholas II as well as liberal and moderate socialists.[26] According to this historical interpretation, it was not popular support, but rather Bolshevik manipulation of the masses and the organization’s ruthlessness and superior structure which enabled it to survive. For these historians, the Bolsheviks’ defeat in the Constituent Assembly elections of November-December 1917 demonstrated popular opposition to the Bolsheviks’ coup, as did the scale and breadth of the Civil War.[27]

These historians saw the organization of the Bolshevik party as proto-totalitarian. Their interpretation of the October Revolution as a violent coup organized by a proto-totalitarian party reinforced the idea that totalitarianism is an inherent part of Soviet history. For them, Stalinist totalitarianism developed as a natural progression from Leninism and the Bolshevik party’s tactics and organization.

Revisionist Historiography

Western historians in the U.S. and Europe originally developed the Revisionist view of the October Revolution. Inspired by the social movements and civil of the 1960s, and further fueled by the opening of some Soviet archives during glasnost, Revisionist historians attempted to reconstruct the actions and aspirations of the masses.[28] These historians were not bound by a common philosophy of history, nor did they agree upon every aspect of their dissent from the two traditional views. However, their willingness to probe, criticize, and reject traditional assumptions distinguish these historians from the other two tendencies. Additionally, the revisionist view heralded the use of “detailed and meticulous specialist research" that aimed to be free from political and ideological influences in carrying out historical analysis.[29]

Reflecting the growing influence of social history in the West, these historians began to shift the focus of the revolution away from high-ranking politicians like Nicholas II, Alexander Kernesky, and Lenin, and to look instead at the experience and aspirations of the workers, soldiers, and peasants.[30] In doing so, these historians challenged both the Soviet and the Western accounts of the revolution. For revisionists, the success of Bolshevism during 1917 does not reflect the party's centralization, unity, and discipline, “but rather its relatively open, flexible and democratic nature."[31] Moreover, these historians held that to understand the October Revolution, it is essential to grasp the social, political, and economic conditions in the Russian Empire that had generated mass discontent. This mass discontent was transformed into support for the Bolshevik party, which the tsarist regime could not constrain. In this view, “it was because Bolshevism articulated mass aspirations so well that the party attracted the support it did and seized power with such ease in October.”[32]

Support for the Revisionist camp of historical interpretation grew and by the 1980s, this view was endorsed by many Western historians, and was also attracting several sympathetic, though limited, reviews from outspoken Soviet historians.[33]

Impact of the Dissolution of the USSR on Historical Research

The dissolution of the USSR had an impact on historical interpretations of the October Revolution. Since 1991, increasing access to large amounts of Soviet archival materials made it possible to re-examine the October Revolution.[34] Though both Western and Russian historians now have access to many of these archives, the impact of the dissolution of the USSR can be seen most clearly in the work of historians in the former USSR. While the disintegration essentially helped solidify the Western and Revisionist views, post-USSR Russian historians largely repudiated the former Soviet historical interpretation of the Revolution.[35] In other words, the established Soviet view of the October Revolution has been challenged, and consequently “Russian historians’ outlook has come closer to that of their Western conferes.”[36] As Stephen Kotkin argues, 1991 prompted “a return to political history and the apparent resurrection of totalitarianism, the interpretive view that, in different ways…revisionists sought to bury.”[37] In other words, after 1991, there has been the revival among some historians of the “continuity thesis,” the idea that there was an uncomplicated, natural evolution from the October Revolution’s organizational structure to Stalin’s Gulags.[38]

Soviet in memoriam of the event

The term "Red October" (Красный Октябрь, Krasnyy Oktyabr) has also been used to describe the events of the month. This name has in turn been lent to a steel factory made notable by the Battle of Stalingrad,[citation needed] a Moscow sweets factory that is well-known in Russia, and a fictional Soviet submarine.

Sergei Eisenstein's film October: Ten Days That Shook the World describes and glorifies the revolution and was commissioned to commemorate the event.

7 November, the anniversary of the October Revolution, was an official holiday in the Soviet Union from 1918 onward and still is in Belarus and Kyrgyzstan.

The October revolution of 1917 also marks the inception of the first communist government in Russia, and thus the first large-scale socialist state in world history. After this Russia became the Russian SFSR and later part of the USSR, which dissolved in late 1991. The Russian SFSR still exists, but in 1991—1993 it was transformed from a Soviet socialist republic into the current Russian Federation of today.

See also

- February Revolution

- Alexander Parvus, the "sponsor" of the Revolution

- Arthur Ransome

- John Reed

- Revolutions of 1917-23

- Russian Civil War

- Russian Revolution (1917)

- Kiev Bolshevik Uprising

- Anna Geifman

Notes

- ^ David Mandel, The petrograd workers and the seizure of soviet power, London, 1984

- ^ a b c d e Cultinfo.ru (Russian)

- ^ Beckett, 2007. p. 526.

- ^ Pipes, 1997. p. 51. "There is no evidence of a Kornilov plot, but there is plenty of evidence of Kerensky's duplicity."

- ^ Service, 2005. p. 54.

- ^ Central Committee Meeting—10 Oct 1917

- ^ a b Beckett, p. 528.

- ^ Argumenty i Fakty newspaper

- ^ Service, 1998.

- ^ John Reed, Ten Days that Shook the World

- ^ Figes, 1996.

- ^ See Encyclopedia of Ukraine online

- ^ See the article on Estonian independence in the Britannica Concise Encyclopedia online

- ^ "Boris Gudz". The Independent (London). 6 January 2007. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/boris-gudz-430985.html.

- ^ Edward Acton, Critical Companion to the Russian Revolution, 1914-1921 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1997), 5.

- ^ Acton, Critical Companion, 5-7.

- ^ Stephen Kotkin, “1991 and the Russian Revolution: Sources, Conceptual Categories, Analytical Frameworks,” The Journal of Modern History 70 (October 1998): 392.

- ^ Paul Blackledge, “Leon Trotsky’s Contribution to the Marxist Theory of History,” Studies in East European Thought (March 2006): 2.

- ^ Acton, Critical Companion, 7.

- ^ Acton, Critical Companion, 8.

- ^ Alter Litvin, Writing History in Twentieth-Century Russia, (New York: Palgrave, 2001), 49-50.

- ^ Roger Markwick, Rewriting History in Soviet Russia: The Politics of Revisionist Historiography, (New York: Palgrave, 2001), 97.

- ^ Markwick, Rewriting History, 102.

- ^ Acton, Critical Companion, 7.

- ^ Acton, Critical Companion, 6-7.

- ^ Acton, Critical Companion, 7

- ^ Acton, Critical Companion, 7-9.

- ^ Kevin Murphy, “Setting the Standard for the Study of the Russian Revolution,” http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showrev.php?id=9856, (May 2011).

- ^ Acton, Critical Companion, 8, 13.

- ^ Acton, Critical Companion, 8-9.

- ^ Acton, Critical Companion, 8.

- ^ Acton, Critical Companion, 10.

- ^ Jacob Heilbrunn, “Review of Cold War Triumphalism,” Journal of Cold War Studies, (2006): 150.

- ^ Kotkin, “1991 and the Russian Revolution,” 385-86.

- ^ Litvin, Writing History, 47.

- ^ Litvin, Writing History, 47-48.

- ^ Kotkin, “1991 and the Russian Revolution,” 385.

- ^ Kevin Murphy, “Can we write the history of the Russian Revolution?,” http://www.isreview.org/issues/57/feat-russianrev.shtml (May 2011).

References

- Acton, Edward (1997). Critical Companion to the Russian Revolution.

- Beckett, Ian F.W. (2007). The Great war (2 ed.). Longman. ISBN 1405812524. http://books.google.com/books?id=CMYbKgcAW88C.

- Mandel, David (1984). The Petrograd Workers and the Soviet seizure of power. London: MacMillan.

- Richard Pipes (27 May 1997). Three "whys" of the Russian Revolution. Vintage Books. ISBN 9780679776468. http://books.google.com/books?id=mdqtQgAACAAJ. Retrieved 8 September 2010.

- Read, Christopher (1996). From Tsars to Soviets.

- Robert Service (2005). A history of modern Russia from Nicholas II to Vladimir Putin. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674018013. http://books.google.com/books?id=eseDgCQK9UkC. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- Service, Robert (1998). A history of twentieth-century Russia. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-40347-9.

- Figes, Orlando (1996). A People's Tragedy. Pimlico.

External links

- The October Revolution Archive

- Let History Judge Russia’s Revolutions, commentary by Roy Medvedev, Project Syndicate, 2007

- October Revolution and Logic of History

Categories:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.