- Nazi concentration camps

-

In the crematorium courtyard, the citizens of Weimar are confronted by U.S soldiers with the corpses found in Buchenwald concentration camp. It was the first photo of the Buchenwald camp to be published.[citation needed]

In the crematorium courtyard, the citizens of Weimar are confronted by U.S soldiers with the corpses found in Buchenwald concentration camp. It was the first photo of the Buchenwald camp to be published.[citation needed]

Nazi Germany maintained concentration camps (in German Konzentrationslager, or KZ) throughout the territories it controlled. The first Nazi concentration camps set up in Germany were greatly expanded after the Reichstag fire of 1933, and were intended to hold political prisoners and opponents of the regime. The term was borrowed from the British concentration camps of the Second Anglo-Boer War.

The number of camps quadrupled between 1939 and 1942 to 300+,[1] as slave-laborers from across Europe, Jews, political prisoners, criminals, homosexuals, gypsies, the mentally ill and others were incarcerated,[2] generally without judicial process. Holocaust scholars draw a distinction between concentration camps (described in this article) and extermination camps, which were established by the Nazis for the industrial-scale mass murder of the predominantly Jewish ghetto and concentration camp populations.

Contents

Camps before the war

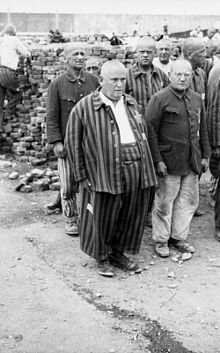

The Dachau camp was created for holding political opponents. In time for Christmas 1933 roughly 600 of the inmates were released as part of a pardoning action. The picture above depicts a speech by camp commander Theodor Eicke to prisoners about to be released.

The Dachau camp was created for holding political opponents. In time for Christmas 1933 roughly 600 of the inmates were released as part of a pardoning action. The picture above depicts a speech by camp commander Theodor Eicke to prisoners about to be released.

Use of the word "concentration" came from the idea of using documents confining to one place a group of people who are in some way undesirable. The term itself originated in the "reconcentration camps" set up in Cuba by General Valeriano Weyler in 1897. Concentration camps had in the past been used by the U.S. against native Americans, by the British in the Boer wars, and wherever the "undesirables" had to be kept in check by those who incarcerated them.

When the Nazis came to power in Germany, they quickly moved to ruthlessly suppress all real or potential opposition. The general public was intimidated through arbitrary psychological terror. Between 1933 and 1945, the special courts (Sondergerichte) set up by the Nazi regime executed 12,000 German nationals.[3] Especially during the first years of their existence these courts "had a strong deterrent effect" against any form of political protest.[4]

The first camp in Germany, Dachau, was founded in March 1933.[5] The press announcement said that "the first concentration camp is to be opened in Dachau with an accommodation for 5,000 persons. All Communists and – where necessary – Reichsbanner and Social Democratic functionaries who endanger state security are to be concentrated there, as in the long run it is not possible to keep individual functionaries in the state prisons without overburdening these prisons."[5] Dachau was the first regular concentration camp established by the German coalition government of National Socialist Workers' Party (Nazi Party) and the Nationalist People's Party (dissolved on 6 July 1933). Heinrich Himmler, then Chief of Police of Munich, officially described the camp as "the first concentration camp for political prisoners."[5]

Dachau served as a prototype and model for the other Nazi concentration camps. Almost every community in Germany had members taken there. The newspapers continuously reported of "the removal of the enemies of the Reich to concentration camps" making the general population more aware of their presence. There were jingles warning as early as 1935: "Dear God, make me dumb, that I may not to Dachau come."[6]

Between 1933 and the fall of Nazi Germany in 1945, more than 3.5 million Germans were forced to spend time in concentration camps and prisons for political reasons,[7][8][9] and approximately 77,000 Germans were executed for one or another form of resistance by Special Courts, courts-martial, and the civil justice system. Many of these Germans had served in government, the military, or in civil positions, which enabled them to engage in subversion and conspiracy against the Nazis.[10]

As a result of the Holocaust, the term "concentration camp" carries many of the connotations of "extermination camp" and is sometimes used synonymously. Because of these ominous connotations, the term "concentration camp", originally itself a euphemism, has been replaced by newer terms such as internment camp, resettlement camp, detention facility, etc., regardless of the actual circumstances of the camp, which can vary a great deal.

Concentration camps during World War II

After September 1939, with the beginning of the Second World War, concentration camps became places where millions of ordinary people were enslaved as part of the war effort, often starved, tortured and killed.[11] During the War, new Nazi concentration camps for "undesirables" spread throughout the continent. According to statistics by the German Ministry of Justice, about 1,200 camps and subcamps were run in countries occupied by Nazi Germany,[12] while the Jewish Virtual Library estimates that the number of Nazis camps was closer to 15,000 in all of occupied Europe[13] and that many of these camps were created for a limited time before being demolished.[13] Camps were being created near the centers of dense populations, often focusing on areas with large communities of Jews, Polish intelligentsia, Communists or Roma. Since millions of Jews lived in pre-war Poland, most camps were located in the area of General Government in occupied Poland, for logistical reasons. The location also allowed the Nazis to quickly remove the German Jews from within the German proper. In 1942, the SS built a network of Extermination camps to systematically kill millions of prisoners by gassing. The extermination camps (Vernichtungslager) and death camps (Todeslager) were camps whose primary function was genocide. The Nazis themselves distinguished between concentration camps and the extermination camps.[14][15]

Internees

The two largest groups containing prisoners in the camps, both numbering in the millions, were the Polish Jews and the Soviet prisoners of war (POWs) held without trial or judicial process. Large numbers of Roma (or Gypsies), ethnic Poles, political prisoners, homosexuals, people with disabilities, Jehovah's Witnesses, Catholic clergy, Eastern European intellectuals and others (including common criminals, as declared by the Nazis). In addition, a small number of Western Allied aviators were sent to concentration camps as spies.[16] Western Allied POWs who were Jews, or whom the Nazis believed to be Jewish, were usually sent to ordinary POW camps; however, a small number were sent to concentration camps under antisemitic policies.[17]

Sometimes the concentration camps were used to hold important prisoners, such as the generals involved in the attempted assassination of Hitler; U-boat Captain-turned-Lutheran pastor Martin Niemöller; and Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, who was interned at Flossenbürg on February 7, 1945, until he was hanged on April 9, shortly before the war’s end.

In most camps, prisoners were forced to wear identifying overalls with colored badges according to their categorization: red triangles for Communists and other political prisoners, green triangles for common criminals, pink for homosexual men, purple for Jehovah's Witnesses, black for Gypsies and asocials, and yellow for Jews.[18]

Treatment

Many of the prisoners died in the concentration camps through deliberate maltreatment, disease, starvation, and overwork, or were executed as unfit for labor. Prisoners were transported in inhumane conditions by rail freight cars, in which many died before reaching their destination. The prisoners were confined to the boxcars for days or even weeks, with little or no food or water. Many died of dehydration in the intense heat of summer or froze to death in winter. Concentration camps also existed in Germany itself, and while they were not specifically designed for systematic extermination, many of their inmates perished because of harsh conditions or were executed.

In the early spring of 1941, the SS – along with doctors and officials of the T-4 Euthanasia Program – introduced the Action 14f13 programme meant for extermination of selected concentration camp prisoners.[19] The Inspectorate of the Concentration Camps categorized all files dealing with the death of prisoners as 14f, and those of prisoners sent to the T-4 gas chambers as 14f13. Under the language regulations of the SS, selected prisoners were designated for "special treatment (German: Sonderbehandlung) 14f13". Prisoners were officially selected based on their medical condition; namely, those permanently unfit for labor due to illness. Unofficially, racial and eugenic criteria were used: Jews, the handicapped, and those with criminal or antisocial records were selected.[20] For Jewish prisoners there was not even the pretense of a medical examination: the arrest record was listed as a physician’s “diagnosis”.[21] In early 1943, as the need for labor increased and the gas chambers at Auschwitz became operational, Heinrich Himmler ordered the end of Action 14f13.[22]

General (later U.S. President) Dwight D. Eisenhower inspecting prisoners’ corpses at the liberated Ohrdruf forced labor camp, 1945

General (later U.S. President) Dwight D. Eisenhower inspecting prisoners’ corpses at the liberated Ohrdruf forced labor camp, 1945

After 1942, many small subcamps were set up near factories to provide forced labour. IG Farben established a synthetic rubber plant in 1942 at Monowitz concentration camp (Auschwitz III); other camps were set up next to airplane factories, coal mines and rocket propellant plants. Conditions were brutal and prisoners were often sent to the gas chambers or killed if they did not work quickly enough.

After much consideration, the extermination of the Jewish prisoners (the “Final Solution”) was announced to high ranking officials at the Wannsee Conference in 1942.[citation needed]

Towards the end of the war, the camps became sites for medical experiments. Eugenics experiments, freezing prisoners to determine how downed pilots were affected by exposure, and experimental and lethal medicines were all tried at various camps. Female prisoners were routinely raped and degraded in the camps.[23]

The camps were liberated by the Allies between 1943 and 1945, often too late to save all the remaining prisoners. For example, when British forces entered Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in 1945, 60,000 prisoners were found alive, but 10,000 died within a week of liberation due to typhus and malnutrition.

Glossary of Terms used at Auschwitz [24]

- Arbeitdienst - internee who assigned work for Kommandos

- Aussenkommandos - inmates who worked outside the camp

- Bekleidungskammer - the inmates' clothing warehouse

- Blocova - the barrack or block chief (women's camp)

- Buna - Synthetic rubber, developed at IG Farben Auschwitz plant. See IG Farben Trial, Subsequent Nuremberg Trials, Leverkusen, Otto Ambrose, Heinrich Bütefisch. [25][26][27]

- Califactorka - the blocova's personal maid

- Canada - warehouse where deportee property was stored for shipment to Germany (then bought by the public)

- Fuehrerstube - S. S. offices

- Esskommando - the food carriers

- Haeftling - internee (camp inmate)

- Kapo - kommando chief

- Koia - crude tier of wood used as a bed for many inmates

- Kommando - work group

- Lager - camp

- Lageraelteste - "queen" of the women's camp

- Lagerkapo - Lageraelteste's assistant

- Lagerstrasse - main road inside the camp

- Lagerruhe - curfew

- Mussulmen - internees reduced to walking skeletons (with almost no willpower remaining)

- Oberarzt - chief S. S. camp physician

- "Organization" - stealing from the Germans, but also included any form of resistance

- Politische Büro - political bureau where documents and records were kept

- Rapportschreiberin - chief camp secretary

- Scheisskommando - latrine-cleaning group

- Schreiberin - scribe (female)

- Schreibstube - offices where roll call reports were sent

- Schutzhaeftling - "protected" prisoners

- Stubendienst - barrack gendarmerie, also food dividers

- "Sport" - punishment for blocovas, officials, and kitchen girls

- Sonderkommandos - special work group (crematory or "krema" workers: allowed to live four months)

- Sonderbehandlung (S. B.) - special handling ("condemned to death")

- Vertreterin - blocova's (female) lieutenant

The British intelligence service had information about the concentration camps, and in 1942 Jan Karski delivered a thorough eyewitness account to the government.Types of camps

According to Moshe Lifshitz,[28] the Nazi camps divided as follows:

- Hostage camps (or death camps): camps where hostages were held and killed as reprisals.

- Labor camps: concentration camps where interned inmates had to do hard physical labor under inhumane conditions and cruel treatment. Some of these camps were sub-camps of bigger camps, or "operational camps", established for a temporary need.

- POW camps: concentration camps where prisoners of war were held after capture. These POW's endured torture and liquidation on a large scale.

- Camps for rehabilitation and re-education of Poles: camps where the intelligentsia of the ethnic Poles were held, and "re-educated" according to Nazi values as slaves.

- Transit and collection camps: camps where inmates were collected and routed to main camps, or temporarily held (Durchgangslager or Dulag).

- Extermination camps: These camps differed from the rest, since not all of them were also concentration camps. Although none of the categories is independent, and each camp could be classified as a mixture of several of the above, and all camps had some of the elements of an extermination camp, systematic extermination of new-arrivals occurred in very specific camps. Of these, four were extermination camps, where all new-arrivals were simply killed – the "Aktion Reinhard" camps (Treblinka, Sobibor and Belzec), together with Chelmno. Two others (Auschwitz and Majdanek) were combined concentration and extermination camps. Others were at times classified as "minor extermination camps".

Post-war use

Though most Nazi concentration and extermination camps were destroyed after the war, some were made into permanent memorials. In Communist Poland, some camps such as Majdanek, Jaworzno, Potulice and Zgoda were used to hold German Prisoners of War, suspected Nazis and collaborators, anti-Communists and other political prisoners, as well as civilian members of the German, Silesian and Ukrainian ethnic minorities. Currently, there are memorials to both camps in Potulice; they have helped to enable a German-Polish discussion on historical perception of World War II. In East Germany (Buchenwald and Sachsenhausen), concentration and extermination camps were used for similar purposes. Dachau concentration camp was used as a prison for arrested Nazis.

See also

- Extermination camp

- German camps in occupied Poland during World War II

- Gulag

- Identification in Nazi camps

- Internment

- Ka-tzetnik

- KZ Manager

- Labor camp

- List of Nazi-German concentration camps

- Nazi crimes against ethnic Poles

- Nazi guards

- NKVD special camps

- Nuremberg Trials

- Persecution of homosexuals in Nazi Germany and the Holocaust

- Nazi concentration camp badges

- Porajmos, the attempted extermination of the Roma people

- The Holocaust

- War crimes

- Research Materials: Max Planck Society Archive

References

- ^ [1] United States Holocaust Memorial Museum: "Nazi Camp System"

- ^ See Nazi concentration camp badges for a more complete system of prisoner identification in Nazi camps.

- ^ Peter Hoffmann "The History of the German Resistance, 1933-1945"p.xiii

- ^ Andrew Szanajda "The restoration of justice in postwar Hesse, 1945-1949" p.25 "In practice, it signified intimidating the public through arbitrary psychological terror, operating like the courts of the Inquisition." "The Sondergerichte had a strong deterrent effect during the first years of their operation, since their rapid and severe sentencing was feared."

- ^ a b c "Ein Konzentrationslager für politische Gefangene In der Nähe von Dachau" (in German). Münchner Neueste Nachrichten ("The Munich Latest News") (The Holocaust History Project). 21 March 1933. http://www.holocaust-history.org/dachau-gas-chambers/photo.cgi?02.

- ^ Janowitz, Morris (September, 1946). "German Reactions to Nazi Atrocities". The American Journal of Sociology (The University of Chicago Press) 52 (Number 2): 141–146. http://www.jstor.org/pss/2770938.

- ^ David Clay, "Contending with Hitler: Varieties of German Resistance in the Third Reich", p.122 (1994) ISBN 0-521-41459-8

- ^ Otis C. Mitchell, "Hitler's Nazi state: the years of dictatorial rule, 1934-1945" (1988), p.217

- ^ Peter Hoffmann "The History of the German Resistance, 1933–1945"p.xiii

- ^ CNN - Army to honor soldiers enslaved by Nazis

- ^ List of concentration camps and their outposts (German)

- ^ a b Concentration Camp Listing Sourced from Van Eck, Ludo Le livre des Camps. Belgium: Editions Kritak; and Gilbert, Martin Atlas of the Holocaust. New York: William Morrow 1993 ISBN 0-6881-2364-3. In this on-line site are published the names of 149 camps and 814 subcamps, organized by country.

- ^ Diary of Johann Paul Kremer

- ^ Overy, Richard. Interrogations, p. 356–7. Penguin 2002. ISBN 978-0-14-028454-6

- ^ One of the best-known examples was the 168 British Commonwealth and U.S. aviators held for a time at Buchenwald concentration camp. (See: luvnbdy/secondwar/fact_sheets/pow Veterans Affairs Canada, 2006, “Prisoners of War in the Second World War” and National Museum of the USAF, “Allied Victims of the Holocaust”.) Two different reasons are suggested for this: the Nazis wanted to make an example of theTerrorflieger (“terror-instilling aviators”), or they classified the downed fliers as spies because they were out of uniform, carrying false papers, or both when apprehended.

- ^ See, for example, Joseph Robert White, 2006, “Flint Whitlock. Given Up for Dead: American GIs in the Nazi Concentration Camp at Berga” (book review)

- ^ “Germany and the Camp System” PBS Radio website

- ^ Holocaust Timeline: The Camps Archived 26 January 2010 at WebCite

- ^ Friedlander, Henry (1995). The Origins of Nazi Genocide: From Euthanasia to the Final Solution. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 144.

- ^ Ibid., pp. 147–8

- ^ Ibid., p. 150

- ^ Morrissette, Alana M.: The Experiences of Women During the Holocaust, p. 7.

- ^ Olga Lengyel, "Five Chimneys: The Story of Auschwitz", Academy Chicago Publishers, 1995

- ^ Josiah E. DuBois Jr., Edward Johnson, "The Devil's Chemists: 24 Conpirators of the International Farben Cartel Who Manufacture Wars", The Beacon Press, 1952

- ^ Joseph Borkin. "The Crime and Punishment of I. G. Farben: The Unholy Alliance Between Hitler and the Great Chemical Combine", Barnes & Nobel, 1997

- ^ Who is I.G. Farben? http://www4.dr-rath-foundation.org/PHARMACEUTICAL_BUSINESS/history_of_the_pharmaceutical_industry.htm#nuremberg

- ^ Moshe Lifshitz, "Zionism". (ציונות), p. 304

External links

- Pages show pictures and videos of the day taken at places connected with World War II (Second World War)

- Yad VaShem—The Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Authority

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Personal Histories - Camps at United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

- The Holocaust History Project

- Official U.S. National Archive Footage of Nazi camps

- Holocaust sites in Germany, Austria, Poland, Czech Republic, France

- Concentration Camps at Jewish Virtual Library

- Memory of the Camps, as shown by PBS Frontline

- [2] Private visit – Aug 2007

- Podcast with one of 2,000 Danish policemen in Buchenwald

- Nazi Concentration Camp Page with links to original documents

The Holocaust - Related articles by country: Belarus

- Estonia

- Latvia

- Lithuania

- Poland

- Norway

- Russia

- Ukraine

Early elements Camps Transit and collectionConcentrationMethods- Inmate identification

- Gas van

- Gas chamber

- Extermination through labor

- Human medical experimentation

- Inmate disposal of victims

Divisions: SS-Totenkopfverbände - Concentration Camps Inspectorate

- Politische Abteilung

- Sanitätswesen

History of the Jews

during World War II- Wannsee Conference

- Operation Reinhard

- Holocaust trains

- Extermination camps

Resistance- Death marches

- Wola

- Bricha

- Displaced persons

Other victims Responsibility OrganizationsIndividualsAftermath Lists - Holocaust survivors

- Victims and survivors of Auschwitz

- Survivors of Sobibor

- Timeline of Treblinka

- Victims of Nazism

- Rescuers of Jews

Resources Remembrance - Days of remembrance

- Memorials and museums

Categories:- Nazi concentration camps

- Nazi SS

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.