- Bełżec extermination camp

-

Bełżec Extermination camp

Belzec extermination camp memorialCoordinates 50°22′18″N 23°27′27″E / 50.37167°N 23.4575°ECoordinates: 50°22′18″N 23°27′27″E / 50.37167°N 23.4575°E Known for Genocide during The Holocaust Location Near Bełżec, German-occupied Poland Built by Richard Wolfgang Thomalla (death camp)

Lorenz Hackenholt (gas chambers)Operated by  SS-Totenkopfverbände

SS-TotenkopfverbändeOriginal use Death First built 1 November 1941 – March 1942 Operational 17 March 1942 – end of June 1943 Number of gas chambers 3 (later 6)[1] Inmates mainly Jews, Roma, Poles Killed est. 434,508–600,000 Liberated by closed before end of war Notable inmates Rudolf Reder, Chaim Hirszman Belzec, Polish spelling Bełżec [ˈbɛu̯ʐɛt͡s], was the first of the Nazi German extermination camps created for implementing Operation Reinhard during the Holocaust. Operating from March 17, 1942 to the end of June 1943, the camp was situated in occupied Poland about 1 km south of the local railroad station of Bełżec in the Lublin district of the General Government.

Between 430,000 and 500,000 Jews are believed to have been killed at Bełżec, along with an unknown number of Poles and Roma;[2][3] only one[4][5] or two Jews are known to have survived Bełżec and the war: Rudolf Reder and Chaim Hirszman.[5] The lack of survivors, who could have given testimony, is the primary reason why this camp is so little known despite the enormous number of victims.

Camp construction and purposes

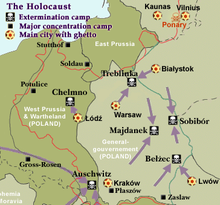

Belzec was situated in the Lublin district forty-seven miles north of the major city of Lviv (Lvov, Lwow), conveniently between the large Jewish populations of southeast Poland and eastern Galicia. Belzec extermination camp, the model for two others in the Aktion Reinhard murder program, started as a labor camp in April 1940, in the course of the Burggraben-project attached to the Lublin reservation in the same area: the reservation was to serve as a pool for forced labour exploited by various small camps like Belzec, to erect defensive works along the Nazi-Soviet demarcation line such as a long anti-tank ditch.[6] While the Burggraben project was shut down by the end of the year due to its inefficiency, Belzec was re-opened in 1942 to finish part of the anti-tank ditch.[6]

On 13 October 1941, Heinrich Himmler gave SS and Police Leader Lublin, SS Brigadeführer Odilo Globocnik, two orders which were closely connected with each other: to start Germanizing the area around Zamość and to start work on the first extermination camp in the General Government near Bełżec. The site was chosen for three reasons: it was situated at the border between the districts Lublin and Galicia, thus indicating its purpose to serve as a killing site for the Jews of both districts; for reasons of transport it lay next to the railroad and the main road between Lublin and Lvov; the northern boundary of the planned death camp was the anti-tank ditch dug a year before by Jewish slave workers of the former forced labour camp. The ditch, originally excavated for military reasons, was likely to serve as the first mass grave. Globocnik's construction expert SS Obersturmführer Richard Thomalla commenced work in early November 1941, using Polish villagers, Globocnik's Trawniki men and, later, Jewish slave workers. The installation was finished by early March 1942 - the camp then started to turn from a labour to a killing camp as envisioned in the Wannsee Conference.[4]

Prior experience of killers in Nazi murders of disabled people

The two commanders of the camp, Kriminalpolizei officers SS-Sturmbannführer Christian Wirth and SS-Hauptsturmführer Gottlieb Hering, had been — in common with almost all of their staff — involved in the Nazi euthanasia Action T4 program since 1940. Wirth had the leading position as a supervisor of all six euthanasia institutions in the Reich; Hering as the non-medical chief of Sonnenstein (Pirna, Saxony) and Hadamar. As a participant of the first T-4 test gassing of handicapped people at Brandenburg, Wirth had been a killing expert from the beginning. He was, therefore, an obvious choice to be the first commandant of the first extermination camp in the General Government. It might have been his proposal to transfer the T-4 technology of killing by carbon monoxide gas in stationary gas chambers to Bełżec, because the comparable technology of mobile gas vans used before December 1941 in the extermination camp Chelmno had proven insufficient for the planned number of victims.[citation needed]

Changes to killing methods

Wirth developed his own ideas on the basis of the experience he had gained in the "Euthanasia" program and decided to supply the fixed gas chamber with gas produced by the internal-combustion engine of a motorcar. Wirth rejected Zyklon B which was later used at Auschwitz. This gas was produced by private firms and its extensive use in Bełżec might have aroused suspicion and led to problems of supply. He therefore preferred a system of extermination based on ordinary, universally available gasoline and diesel fuel. For economic and transport reasons, Wirth did not make use here of industrial bottled carbon monoxide as in T-4, but had the same gas supplied by a large engine (although witnesses differ as to its type, most probably it was a petrol engine), whose exhaust fumes, poisonous in an enclosed space, were led by a system of pipes into the gas chambers. For very small transports of Jews and Gypsies over a short distance, a minimized version of the gas van technology was used in Bełżec: T-4 man and first operator of the gas chambers, SS Hauptscharführer Lorenz Hackenholt,[7] rebuilt an Opel-Blitz post office vehicle with the help of a local craftsman into a small gas van.[8] A member of the staff testified that the Jewish office girls were murdered in this car on the very last day of Bełżec.[citation needed]

Concealment of camp's purpose from victims

The wooden gas chambers were disguised as the barracks and showers of a labor camp, so that the victims would not realize the true purpose of the site, and the process was conducted as quickly as possible: people were forced to run from the trains to the gas chambers, leaving them no time to absorb where they were or to plan a revolt. Finally, a handful of Jews were selected to perform all the manual work involved with extermination (removing the bodies from the gas chambers, burying them, sorting and repairing the victims' clothing, etc.). The extermination process itself was conducted by Hackenholt, guards, and a Jewish aide.[9] The Jewish Sonderkommandos were killed periodically and replaced by new arrivals, so that they would neither organize a revolt nor survive to tell about the camp.

Camp operation

Eventually, the extermination camp consisted of two subcamps: Camp I, which included the barracks of the Ukrainians, the workshops and barracks of the Jews, the reception area with two undressing barracks, and Camp II, which contained the gas chambers and the mass graves. The two camps were connected by a narrow corridor called der Schlauch, or "Tube". The German guards and the administration were housed in two cottages outside the camp across the road.

Bełżec's three gas chambers began operating officially on March 17, 1942, the first of the Operation Reinhard camps to begin killing.[3] Its first victims were Jews deported from Lublin and Lwow. There were many technical difficulties in this first attempt at mass extermination. The gas chamber mechanisms were problematic, and usually only one or two were working at any given time, causing a backlog. Furthermore, the corpses were buried in pits covered with only a narrow layer of earth. The bodies often swelled in the heat as a result of putrefaction and the escape of gases, and the covering of earth split. This latter problem was corrected in other death camps with the introduction of crematoria.

It was soon realized that the original three gas chambers were insufficient for completing the task at hand, especially with the growing number of arrivals from Kraków and Lviv. A new complex with six gas chambers made of concrete, each 4 × 5 or 8 meters, was erected, and the wooden gas chambers were dismantled. The new facility, which could handle over 1,000 victims at a time, was imitated by the other two Operation Reinhard extermination camps: Sobibor and Treblinka. There was a sign on the new building that read "Stiftung Hackenholt" or Hackenholt Foundation named after the SS NCO who designed it.[10] In December 1942, the last shipment of Jews arrived in Bełżec. By that time, the Jews in the area served by Bełżec had been almost entirely murdered, and it was felt that the new facilities under construction at Auschwitz-Birkenau could kill the rest.[citation needed]

Closure and dismantlement

A last train with 300 Jewish prisoners, told to depart for Germany but instead sent to Sobibor for gassing, departed in late June 1943 as the closing act of the camp.[11][12] As part of the Nazi plan called Sonderaktion 1005, bodies were exhumed and then cremated and bone fragments pulverized. The German and Ukrainian personnel then dismantled the camp and reforested the site with firs and wild lupines.[11] Any equipment of potential reuse were taken to the concentration camp Majdanek. Wirth's house and the neighboring SS building, which had been the property of the Polish Railway before the war, were not demolished.

When the staff left, the local population from the surrounding villages started large-scale excavations on the camp site, searching for gold and valuables.[11] These diggings were so extensive that the area was covered by human remains of all kind, and the Nazis' efforts to disguise the site were thwarted.[11] In response, SS personnel were again ordered to the camp site to turn it into a farm, with one Ukrainian SS guard assigned to reside there permanently with his family.[11] This model for guarding and disguising former camp sites was later adopted in Treblinka and Sobibor.[11]

Subsequent careers of camp personnel

The camp's first known commander, Christian Wirth, lived very close to the camp in a house which also served as a kitchen for the SS as well as an armoury.[13] He later moved to the Lublin airfield site to oversee Operation Reinhard. He was transferred to San Sabba, a former rice mill in Trieste, Italy. He received the Iron Cross in April 1944. He was killed the following month by partisans whilst travelling in an open topped car in what is today western Croatia. His successor Gottlieb Hering served after the war for a short time as the chief of Criminal Police of Heilbronn and died in autumn 1945 in a hospital. Lorenz Hackenholt survived the war, but disappeared in 1945.[8] British historian Michael Tregenza may have come close to finding Hackenholt in 1990 and his colleague Alan Heath suggested that he had located where Hackenholt may have been hiding in the 1960s.[citation needed]

Only seven former members of the SS-Sonderkommando Belzec were indicted in Munich, but only one of them, Josef Oberhauser, was brought to trial in 1965 and sentenced to 4 years and 6 months in prison, half of which he served before being released.

Camp guards

Bełżec camp guards included Germans (Volksdeutsche) and former Soviet prisoners of war.[14][15]

Before they were sent as guards to the concentration camps, most Soviet POWs who served as camp guards underwent special training in Trawniki, originally a holding center for refugees and Soviet POWs whom the Security Police and SD had designated potential collaborators or dangerous persons.[16]

Kurt Gerstein's testimony

SS Lt. Kurt Gerstein, who worked in the SS medical service, was ordered to deliver a shipment of Zyklon B to Bełżec. He was so shocked by what he saw that he immediately buried the canisters of poison gas, and confessed his experiences to the Swedish diplomat Göran von Otter in a train from Warsaw to Berlin, where they met on August 20. He describes how he arrived at Bełżec on August 19 (another source gives the date as August 18)[10] where he witnessed the unloading of 45 train cars crowded with 6,700 Jews, many of whom were already dead, but the rest were marched naked to the gas chambers, where:

Unterscharführer Hackenholt was making great efforts to get the engine running. But it doesn't go. Captain Wirth comes up. I can see he is afraid because I am present at a disaster. Yes, I see it all and I wait. My stopwatch showed it all, 50 minutes, 70 minutes, and the diesel did not start. The people wait inside the gas chambers. In vain. They can be heard weeping, "like in the synagogue," says Professor Pfannenstiel, his eyes glued to a window in the wooden door. Furious, Captain Wirth lashes the Ukrainian assisting Hackenholt twelve, thirteen times, in the face. After 2 hours and 49 minutes—the stopwatch recorded it all—the diesel started. Up to that moment, the people shut up in those four crowded chambers were still alive, four times 750 persons in four times 45 cubic meters. Another 25 minutes elapsed. Many were already dead, that could be seen through the small window because an electric lamp inside lit up the chamber for a few moments. After 28 minutes, only a few were still alive. Finally, after 32 minutes, all were dead...Dentists hammered out gold teeth, bridges and crowns. In the midst of them stood Captain Wirth. He was in his element, and showing me a large can full of teeth, he said: "See for yourself the weight of that gold! It's only from yesterday and the day before. You can't imagine what we find every day—dollars, diamonds, gold. You'll see for yourself! "[17][18]

Death toll

Eugeniusz Strojt, in an article in the Bulletin of the Main Commission for Investigation of the German Crimes in Poland, estimated the people murdered in Bełżec as 600,000.[citation needed] This number became widely accepted in literature. Raul Hilberg gave a figure of 550,000.[19] Y. Arad accepted 600,000[14] as minimum, and the sum in his table of Bełżec deportations exceeded 500,000.[14] J. Marszalek calculated 500,000.[citation needed] British historian Robin O'Neil once gave an estimate of about 800,000 (based on his investigations at the site).[20] Dieter Pohl and Peter Witte[21] gave estimate of 480,000 to 540,000. Michael Tregenza stated that it would have been possible to have buried up to one million victims on the site although the true death toll is probably around half of that amount.

The crucial piece of evidence in the debate was published in 2001 by Stephen Tyas and Peter Witte.[21] It was a telegram sent by Hermann Höfle, Operation Reinhard's Chief of Staff, which indicates that 434,508 Jews were killed in Bełżec through December 31, 1942. As the camp had ceased to operate for mass killings by then, this figure needs to be treated as almost absolute. After this period a sonderkommando of up to 500 people worked in the camp, disinterring the bodies and burning them. The sonderkommando was transported to Sobibor extermination camp in around August 1943 and murdered on arrival.

The difference between this "low-end" figure and other estimates can be explained by the lack of exact and detailed sources on the deportations statistics. Thus, Y. Arad writes, that he had to rely, in part, on Yizkor books, which were not guaranteed to give the exact estimates of the numbers of deportees. He also had to rely on partial German railway documentation, from the numbers of trains could be gleaned. But here also assumptions had to be made about the number of persons per train.[14] Considering the vagueness of primary sources, many old scholarly estimates are not far off the mark.[citation needed]

It should also be noted that it is not completely clear whether the Jews who died in transit are included in the final sum.[citation needed] Considering the aim of compiling such a statistic (which was to know the overall number of the victims of the "Final Solution"—Hoefle's numbers were used in Korherr Report) they probably were included.[citation needed] Also, the sources like Westermann's report[22] contain the exact data about the number of deported persons, but only estimates of the numbers of those who died in transit, the fact which also hints that they were included in the final sum, because it would be hard for the authorities in Bełżec to learn the exact number of those murdered, excluding the dead in transport.

Remains of the camp

From late 1997 until early 1998, a thorough archaeological survey of the site was conducted as there was no memorial yet at the site. The survey was headed by Andrzej Kola, director of the Underwater Archaeological Department at the University of Torun, and Mieczyslaw Gora, senior curator of the Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology in Lodz. The team identified the railway sidings and remains of a number of buildings. They also found 33 mass graves, the largest of which were 210 by 60 feet. The team estimated that they had found 15,000 unburned bodies, and "The largest mass graves ... contained unburned human remains (parts and pieces of skulls with hair and skin attached) and entire bodies preserved in wax-fat transformation. The foul smelling bottom layer of the graves consisted of several inches to a meter thick of human fat resembling black soap. One grave contained uncrushed human bones so closely packed that the drill could not penetrate."[23]

Postwar commemoration

Scrawled with a Pencil in the Sealed Cattle Car, a poem by Dan Pagis, forms part of the modern memorial.

As a result of Nazi efforts to erase evidence of the camp's existence near the war's end, almost all traces of the camp disappeared from the surface of the site. The mass graves of the camp's victims remained, however, and in the postwar years some people, possibly local inhabitants, disturbed them to look for any valuables buried with the victims. Pursuit of the perpetrators continued into the second half of the 1950s.[24][dead link]

In the 1960s the area of the former camp was fenced off, and a few small monuments were placed on the site. The fenced area did not correspond to the actual area of the camp during its operation, and so some commercial development took place on areas formerly belonging to it. Due to the isolated location on Poland's eastern border, only a very small number of people visited the former camp before 1988. The site was largely forgotten and poorly maintained.

Following the collapse of communism in 1989, the situation slowly changed. As the number of visitors to Poland interested in Holocaust sites increased, more of them came to Bełżec. Many reacted negatively to the unkept state of the grounds. In the late 1990s extensive investigations were carried out on the camp grounds to determine precisely the camp's extent and provide greater understanding of its operation. Buildings constructed after the war on the camp grounds were removed. In 2004, a large new monument commemorating the camp's victims was unveiled.

See also

Notes

- ^ Yitzhak Arad (1987). Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka: The Operation Reinhard Death Camps, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, pg. 73.

- ^ Belzec Death Camp Memorial, Poland (University of Minnesota)

- ^ a b "Belzec", USHMM. Accessed February 5, 2008.

- ^ a b Bergen, Doris (2003). War & genocide: a concise history of the Holocaust Critical issues in history. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 178. ISBN 0847696316.

- ^ a b "Belzec Death Camp: "Remember Me"" (in English). Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team. 2007. http://www.holocaustresearchproject.org/ar/belzec/belzecrememberme.html. Retrieved 2 September 2011.

- ^ a b Schwindt, Barbara (2005). Das Konzentrations- und Vernichtungslager Majdanek: Funktionswandel im Kontext der "Endlösung". Königshausen & Neumann. p. 52. ISBN 3826031237.

- ^ Tregenza, Michael, "The ‘Disappearance’ of SS-Hauptscharfuhrer Lorenz Hackenholt -- A Report on the 1959-63 West German Police Search for Lorenz Hackenholt, the Gas Chamber Expert of the Aktion Reinhard Extermination Camps", 2000, at Mazel on-line library

- ^ a b Klee, The Good Old Days, at pages 230, 237, 241, and 296.

- ^ Pfannenstiel, Wilhelm, "Statement" given 25 April 1960, translated and reprinted in Klee, The Good Old Days, at pages 238 to 244.

- ^ a b Gerstein, Kurt, "Report" dated 4 May 1945, excerpted, translated, and reprinted in Klee, The Good Old Days, at page 242

- ^ a b c d e f Yitzhak Arad, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka: The Operation Reinhard Death Camps, Indiana University Press, 1999, p.371, ISBN 0253213053

- ^ "United States Holocaust Memorial Museum website: Belzec". http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/en/article.php?ModuleId=10005191. Retrieved 8 October 2010.

- ^ YouTube - Belzec - the house of Christian Wirth

- ^ a b c d Yitzhak Arad, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka. The Operation Reinhard Death Camps, Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis, 1987 ISBN 978-0253342935

- ^ Reder, Rudolf, Belzec, Panstwowe Muzeum Oswiecim – Brezezinka.

- ^ Trawniki (Holocaust Encyclopedia -- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum)

- ^ Arad, Yitzhak (1987). Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka: The Operation Reinhard Death Camps. Indiana University Press. pp. 102. ISBN 978-0253342935.

- ^ Another translation of this document is found at Klee, The Gold Old Days, at page 242.

- ^ Raul Hilberg, The Destruction of the European Jews, Yale University Press, 2003, revised hardcover edition, ISBN 0-300-09557-0

- ^ A Reassessment: Resettlement Transports to Belzec, March-December 1942. Robin O'Neil. Accessed December 6, 2009.

- ^ a b Peter Witte and Stephen Tyas, A New Document on the Deportation and Murder of Jews during "Einsatz Reinhardt" 1942, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, Vol. 15, No. 3, Winter 2001, ISBN 0-19-922506-0

- ^ The Westermann Report

- ^ "Archeologists reveal new secrets of Holocaust", Reuters News, 21 July 1998

- ^ http://www.belzec.org.pl/upamietnienie.php?site=dawne&id=1

References

- Arad, Yitzhak, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka. The Operation Reinhard Death Camps, Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis, 1987 ISBN 978-0253342935

- (German) Fahlbusch, Jan H., “Im Zentrum des Massenmordes. Ernst Zierke im Vernichtungslager Belzec”, in: Wojciech Lenarczyk (Ed.), KZ-Verbrechen. Beiträge zur Geschichte der nationalsozialistischen Konzentrationslager. Metropol, Berlin 2007. ISBN 978-3-938690-50-5

- Hilberg, Raul, The Destruction of the European Jews, Yale University Press, 2003, revised hardcover edition, ISBN 0-300-09557-0

- Klee, Ernst, Dressen, Willi, and Riess, Volker, "The Good Old Days" -- The Holocaust as Seen by its Perpetrators and Bystanders, (translation by Deborah Burnstone) MacMillan, New York, 1991 ISBN 0-02-917425-2

- Musial, Bogdan, “The Origins of ‘Operation Reinhard’: The Decision-Making Process for the Mass Murder of the Jews in the Generalgouvernment”, Yad Vashem Studies 28 (2000): 113-153.

- (German) Rückerl, Adalbert (Ed.), Nationalsozialistische Vernichtungslager im Spiegel deutscher Strafprozesse. Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka, Chelmno, 2nd ed., dtv, München 1978, ISBN 3-423-02904-X

- Reder, Rudolf, Belzec, Kraków, 1946

- Witte, Peter, and Tyas, Stephen, “A New Document on the Deportation and Murder of Jews during ‘Einsatz Reinhardt 1942’”, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, Vol. 15, No. 3, Winter 2001, ISBN 0-19-922506-0

External links

- Bełżec Museum -- Miejsce Pamieci w Bełzcu

- The Belzec Death Camp

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum - Belzec and Timeline

- Yad Vashem - About the Holocaust - Belzec

- Bonnie M. Harris, The Belzec Memorial Site

- Belzec Complete Book and Research by Robin O'Neil

The Holocaust in Poland - Main article: The Holocaust

- Related articles by country:

- Belarus

- Estonia

- Latvia

- Lithuania

- Norway

- Russia

- Ukraine

Camps, ghettos and operations Camps ExterminationMass shootings Ghettos - List of 267 Jewish ghettos set up in German-occupied Poland (1939–1942)

- Będzin

- Białystok

- Brest

- Częstochowa

- Grodno

- Kraków

- Lvov (Lwów)

- Łódź

- Lubartów

- Lublin

- Międzyrzec Podlaski

- Radom

- Sosnowiec

- Warsaw

Other atrocities Perpetrators, participants, organizations, and collaborators Major perpetrators Organizers- Josef Bühler

- Eichmann

- Eicke

- Ludwig Fischer

- Hans Frank

- Globocnik

- Glücks

- Greiser

- Himmler

- Hermann Höfle

- Fritz Katzmann

- Wilhelm Koppe

- Friedrich-Wilhelm Krüger

- Kutschera

- Erwin Lambert

- Ernst Lerch

- Oswald Pohl

- Reinefarth

- Scherner

- Seyss-Inquart · Sporrenberg

- Streckenbach

- Thomalla

- Otto Wächter

- Wisliceny

Camp command- Aumeier

- Richard Baer

- Boger

- Braunsteiner

- Eberl

- Kurt Franz

- Karl Frenzel

- Karl Fritzsch

- Göth

- Grabner

- Hartjenstein

- Hering

- Höss

- Hössler

- Josef Kramer

- Liebehenschel

- Maria Mandel

- Matthes

- Michel

- Johann Niemann

- Oberhauser

- Reichleitner

- Heinrich Schwarz

- Stangl

- Gustav Wagner

- Christian Wirth

Gas chamber executioners- Erich Bauer

- Bolender

- Hackenholt

- Klehr

- Hans Koch

- Herbert Lange

Ghetto command- Wolfgang Birkner

- Blobel

- Felix Landau

- Schaper

- Schöngarth

- von Woyrsch

Personnel Camp guardsBy campOrganizations Collaborators JewishEstonian, Latvian,

Lithuanian, Belarusian

and UkrainianOther nationalities- Arajs Kommando

- Ukrainian Auxiliary Police

- Ukrainian collaboration

- Lithuanian Security Police

- Trawniki

- Ypatingasis būrys

- Pieter Menten

Resistance: Judenrat, victims, documentation and technical Organizations Uprisings Leaders Judenrat - Jewish Ghetto Police

- Adam Czerniaków

- Mordechai Chaim Rumkowski

Victim Lists Ghettos- Kraków

- Łódź

- Lvov (Lwów)

- Warsaw

Camps- Auschwitz

- Bełżec

- Chełmno

- Gross-Rosen

- Izbica

- Kraków-Płaszów

- Majdanek

- Sobibor

- Soldau

- Stutthof

- Trawniki

- Treblinka

Documentation Nazi sources- Auschwitz Album

- Frank Memorandum

- Höcker Album

- Höfle Telegram

- Katzmann Report

- Korherr Report

- Nisko Plan

- Posen speeches

- Special Prosecution Book-Poland

- Stroop Report

- Wannsee Conference

Witness accounts- Graebe affidavit

- Gerstein Report

- Vrba-Wetzler report

- Witold's report

ConcealmentTechnical and Logistics - Identification in camps

- Gas chamber

- Gas van

- Holocaust train

- Human medical experimentation

- Zyklon B

Aftermath, trials and commemoration Aftermath Trials West German trials- Frankfurt Auschwitz Trials

- Treblinka trials

Polish, East German, and Soviet trialsMemorials Righteous among the Nations - Polish Righteous among the Nations

- Rescue of Jews by Poles during the Holocaust

- Albert Battel

- Hermann Friedrich Graebe

- Andrey Sheptytsky

- Oskar Schindler

Categories:- World War II sites

- 1942 establishments

- 1942 disestablishments

- 1942 in Poland

- Bełżec extermination camp

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.