- Majdanek concentration camp

-

"Majdanek" redirects here. For other uses, see Majdanek (disambiguation).

Majdanek Concentration camp

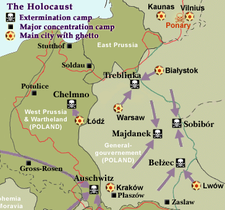

Nazi extermination camps in occupied Poland (marked with black and white skulls)Coordinates 51°13′13″N 22°36′00″E / 51.220325°N 22.60007°ECoordinates: 51°13′13″N 22°36′00″E / 51.220325°N 22.60007°E Other names Lublin Known for Genocide during the Holocaust Location Near Lublin, German-occupied Poland Operated by  SS-Totenkopfverbände

SS-TotenkopfverbändeOriginal use Forced labor Operational October 1, 1941 — July 22, 1944 Inmates mainly Jews Killed est. 78,000 Liberated by Soviet Union, July 22, 1944 Majdanek was a German Nazi concentration camp on the outskirts of Lublin, Poland, established during the German Nazi occupation of Poland. The camp operated from October 1, 1941 until July 22, 1944, when it was captured nearly intact by the advancing Soviet Red Army. Although conceived as a forced labor camp and not as an extermination camp, over 79,000 people[1] died there (59,000 of them Polish Jews) during the 34 months of its operation.

The name 'Majdanek' ("little Majdan") derives from the nearby Majdan Tatarski ("Tatar Maidan") district of Lublin, and was given to the camp in 1941 by the locals, who were aware of its existence. In Nazi documents, and for reasons related to its funding, Majdanek was initially "Prisoner of War Camp of the Waffen-SS in Lublin". It was renamed "Konzentrationslager Lublin" (Concentration Camp Lublin) in February 1943.

Among German Nazi concentration camps, Majdanek was unusual in that it was located near a major city, not hidden away at a remote rural location.[2] It is also notable as the best-preserved concentration camp of the Holocaust - there had been too little time for the Nazis to destroy the evidence before the Red Army arrived.[3]

Contents

History

Construction

"Konzentrationslager Lublin" (Concentration Camp Lublin), the official name of the Majdanek concentration camp, was established in October 1941, on Heinrich Himmler's orders to Odilo Globocnik, following the SS commander's visit to Lublin on 17 and 20 July 1941. Himmler's initial order was for a camp to hold "25,000 to 50,000" prisoners.

Following the large numbers of Soviet prisoners of war captured during the Battle of Kiev, the number was subsequently raised to 50,000 and construction for that many began on October 1, 1941 (as it did also in Auschwitz-Birkenau, which had received the same order). In early November, the plans were then extended to 125,000, and in December to 150,000, and in March 1942 to 250,000 Soviet prisoners of war.

Construction began with 150 Jewish laborers from Globocnik's Lublin camp, where the laborers then returned each night. Later the workforce included 2,000 Red Army POWs, who however had to survive extreme conditions, including sleeping out in the open. By mid-November only 500 of them were still alive, of which at least 30% were incapable of further labor. In mid-December, barracks for only 20,000 were ready when a typhus epidemic broke out, and by January 1942 all the forced laborers—POWs as well as Jews—were dead. All work ceased until March 1942, when new prisoners arrived. Although the camp did eventually have the capacity to hold approximately 50,000 prisoners, it did not grow significantly beyond that size.

In operation

In July 1942, Himmler visited Belzec, Sobibor, and Treblinka, that is, the three camps built specifically for Operation Reinhard—the plan to eliminate Polish Jewry (cf. "Solution of the Jewish Question") in the five districts of occupied Poland that constituted the Nazi Generalgouvernement. Those camps had begun operations in respectively March, May and July of that year. Subsequently, Himmler issued an order that the deportation of Jews to the camps be completed by the end of 1942.

However, due to the need for Jewish manpower for the war effort, some laborers were temporarily spared, and were (for a time) either kept in the ghettos, such as the one in Warsaw (which became a concentration camp after the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising), or sent to labor camps such as Majdanek where they worked primarily at the Steyr-Daimler-Puch weapons/munitions factory.

By mid-October 1942 the camp held 9,519 registered prisoners, of which 7,468 (or 78.45%) were Jews, and another 1,884 (19.79%) were non-Jewish Poles. By August 1943, there were 16,206 prisoners in the main camp, of which 9,105 (56.18%) were Jews and 3,893 (24.02%) were non-Jewish Poles.[4] Minority contingents included Belarusians, Ukrainians, Russians, Germans, Austrians, Slovenes, Italians, and French and Dutch nationals. According to the data from the official Majdanek State Museum, 300,000 persons were inmates of the camp at one time or another. The prisoner population at any given time was much lower.

From October 1942 onwards, Majdanek also had female overseers, SS troopers who had been trained at the Ravensbrück concentration camp. These women included Elsa Erich, Hermine Braunsteiner, Hildegard Lächert and Rosy Suess (or Süss).

Within the general framework of Operation Reinhard, Majdanek functioned as sorting and storage depot for property and valuables taken from the victims at the killing centers in Belzec, Sobibor, and Treblinka.[4] Although Majdanek also occasionally functioned as a killing center for Jews, this was initially not as systematic as in the three specifically Operation Reinhard camps: Of the more than 2,000,000 Jews killed in the course of Operation Reinhard,[5] 59,000 (of 78,000 altogether)[1][6] were killed in Majdanek.

Majdanek did not initially have subcamps. These were incorporated in early autumn 1943 when the remaining forced labor camps around Lublin (Budzyn, Trawniki, Poniatowa, Krasnik, Pulawy, and the "Airstrip" and Lipowa camps) became sub-camps of Majdanek.

Operation Reinhard continued until early November 1943, when the last Generalgouvernement Jews were exterminated as part of Operation "Harvest festival". With respect to Majdanek, the most notorious of this wave of executions occurred on November 3, 1943 when 18,400[7] Jews were killed on a single day. On November 4, 25 Jews who had succeeded in hiding during the killings of the day before were found and executed. Another 611 prisoners, 311 women and 300 men, were commanded to sort through the clothes and remains of the dead. The men were at first commanded to bury the dead, but were later assigned to Sonderkommando 1005, where they had to exhume the same bodies for cremation. The men were then themselves executed. The 311 women were subsequently sent to Auschwitz where they were gassed. By the end of Operation "Harvest Festival," Majdanek had only 71 Jews left (out of a total of 6,562 prisoners).[4]

Executions of the remaining prisoners continued at Majdanek in the months thereafter. Between December 1943 and March 1944, Majdanek received approximately 18,000 so-called "invalids," many of whom where subsequently gassed with Zyklon B (carbon monoxide was used in the very early period). Executions by firing squad continued as well, with 600 shot on January 21, 1944, 180 shot on January 23, 1944, and 200 shot on March 24, 1944.

In late July 1944, with Soviet forces rapidly approached Lublin, the Germans hastily evacuated the camp. But the staff had only succeeded in partially destroying the crematoria before Soviet Red Army troops arrived on July 24, 1944,[3][8] making Majdanek the best-preserved camp of the Holocaust. It was the first major concentration camp liberated by Allied forces, and the horrors found there were widely publicised.[9]

Although 1,000 inmates had previously been forcibly marched to Auschwitz (of whom only half arrived alive), the Red Army still found thousands of inmates, mainly POWs, still in the camp and ample evidence of the mass murder that had occurred there.

Camp commanders

- SS-Standartenführer - Karl Otto Koch (September 1941 to July 1942)

- SS-Sturmbannführer - Max Kögel (August 1942 to October 1942)

- SS-Obersturmführer - Hermann Florstedt (October 1942 to November 3, 1943)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer - Martin Gottfried Weiss (November 4, 1943 to May 18, 1944)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer - Arthur Liebehenschel (May 19, 1944 to July 22, 1944)

Assistance from outside

The prisoners were able to communicate with the outside world through letters smuggled out by civilian workers that were allowed to enter the camp to work there with the prisoners.[10] After the war, many such letters were donated by their recipients to the camp museum.[10] In 2008 the museum held a special exhibition displaying a selection of those letters.[10]

From February 1943 onwards the Germans allowed the Polish Red Cross and Central Welfare Council to bring in food for the prisoners to the camp.[10] Prisoners could also receive food packages via the Polish Red Cross addressed to them by name. The Majdanek Museum archives document 10,300 prisoners that received such packages.[11]

Aftermath

In August 1944, the Soviets converted the camp into a museum and convened a special Polish-Soviet commission to investigate and document the crimes committed at Majdanek.[12] This effort constitutes one of the first attempts to document the Nazi crimes.

Some Nazi personnel of the camp were prosecuted immediately after the war, and some in the decades afterward. In November and December 1944, four SS Men and two kapos were placed on trial; one committed suicide and the rest were hanged on December 3, 1944.[13] The last major, widely publicized prosecution of 16 SS members from Majdanek (Majdanek-Prozess in German) took place from 1975 to 1981 in West Germany. However, of the 1,037 SS members who worked at Majdanek and are known by name, only 170 were prosecuted. This was due to a rule applied by the West German justice system that only those directly involved in the murder process could be charged.

In July 1969, on the 25th anniversary of its liberation, a large monument designed by Wiktor Tołkin (a.k.a. Victor Tolkin) was constructed at the site. It consists of two parts: a large gate monument at the camp's entrance and a large mausoleum holding ashes of the victims at its opposite end.

In October 2005, in cooperation with the Majdanek museum, four Majdanek survivors returned to the site and enabled archaeologists to find some 50 objects which had been buried by inmates, including watches, earrings, and wedding rings.[14][15] According to the documentary film Buried Prayers, this was the largest reported recovery of valuables in a death camp to date. Interviews between government historians and Jewish survivors were not frequent before 2005.[15]

In December 2005, construction work started on a large trade and entertainment complex near Lipowa (named Lindenstraße during the occupation) and Sklodowskiej streets in Lublin, where a Majdanek sub-camp existed between 1940 and 1944.[citation needed] The main investor in the complex is the Plaza Centers Group, which (according to its website) is a member of the Europe Israel Group controlled by founder Mordechay Zisser.

In April 2006, the musical Jesus Christ Superstar was slated to play at the Majdanek museum,[16] but was then canceled over concerns of impropriety.

The camp today occupies about half of its original 2.7 km2 (ca. 670 acres), and—but for the former buildings—is mostly bare. A fire in August 2010 destroyed one of the wooden buildings that was being used as a museum to house seven thousand pairs of prisoners' shoes.[17] The city of Lublin has tripled in size since the end of World War II, and even the main camp is today within the boundaries of the city of Lublin. It is clearly visible to many inhabitants of the city's high-rises, a fact that many visitors remark upon. The gardens of houses and flats border on and overlook the camp.

Death toll

The Soviets initially overestimated the number of deaths, claiming in July 1944 that there were no fewer than 400,000 Jewish victims, and the official Soviet count was of 1.5 million victims of different nationalities,[18] Independent Canadian journalist Raymond Arthur Davies, who was based in Moscow and on the payroll of the Canadian Jewish Congress,[19][20] visited Majdanek on August 28, 1944. The following day he sent a telegram to Saul Hayes, the executive director of the Canadian Jewish Congress. It states: "I do wish [to] stress that Majdanek where one million Jews and half a million others [were] killed"[21] and "You can tell America that at least three million [Polish] Jews [were] killed of whom at least a third were killed in Majdanek"[22] though this estimate was never taken seriously by scholars.

In 1961, Raul Hilberg estimated the number of the Jewish victims at 50,000, though at the time other sources, including the camp museum, officially estimated 100,000 Jewish victims and up to 200,000 non-Jews killed.[1]

In 1992, Czesław Rajca published a lower estimate of 235,000; it was displayed at the camp museum.[1]

The 2005 research by the Head of Scientific Department at Majdanek Museum, historian Tomasz Kranz indicates that there were 79,000 victims, 59,000 of whom were Jews.[1][6]

The differences in estimates stem from different methods used for estimating and the amounts of evidence available to the researchers. The Soviet figures relied on the most crude methodology, also used to make early Auschwitz estimates—it was assumed that the number of victims more or less corresponded to the crematoria capacities. Later researchers tried to take much more evidence into account, using records of deportations and population censuses, as well as the Nazis' own records. Hilberg's 1961 estimate, using these records, aligns closely with Kranz's report.

Notable inmates

- Halina Birenbaum - writer, poet and translator

- Marian Filar - pianist

- Otto Freundlich - one of the artists included in the Nazis' 1937 "Degenerate Art" exhibition

- Israel Gutman - historian

- Henio Zytomirski - child becoming an icon of the Holocaust in Poland.

- Dmitry Karbyshev - Soviet general, Hero of the Soviet Union

- Omelyan Kovch - Ukrainian priest

- Igor Newerly - writer

- Vladek Spiegelman,[15] whose story is the basis for Art Spiegelman's Maus.

- Rudolf Vrba - transferred to Auschwitz, from which he escaped, and about which he co-authored the Vrba-Wetzler report, one of the first inside reports of the camp, and published during wartime.

- Mietek Grocher - Survived nine different camps. Now a lecturer residing in Västerås, Sweden. Author of Jag överlevde (eng. I Survived).

- Maryla Husyt Finkelstein - Late mother of the author and Middle East critic Dr Norman Finkelstein.

References

- ^ a b c d e Reszka, Paweł (2005-12-23). "Majdanek Victims Enumerated. Changes in the history textbooks?". Gazeta Wyborcza. Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum. http://en.auschwitz.org.pl/m/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=44&Itemid=8. Retrieved 2010-04-13.

- ^ Rosenberg, Jennifer (2008), "Majdanek: An Overview", 20th Century History, about.com, http://history1900s.about.com/library/holocaust/aa092099.htm.

- ^ a b http://ww2db.com/battle_spec.php?battle_id=136

- ^ a b c Staff Writer (2006), "Lublin/Majdanek Concentration Camp: Overview", United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, ushmm.org, http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/article.php?lang=en&ModuleId=10005190.

- ^ (PDF) Aktion Reinhard, Shoah Resource Center, The International School for Holocaust Studies, yadvashem.org, 2004, p. 2, http://www1.yadvashem.org/odot_pdf/microsoft%20word%20-%205724.pdf.

- ^ a b Kranz, Tomasz (2005), Ewidencja zgonow i smiertelnosc wiezniow KL Lublin, 23, Lublin: Zeszyty Majdanka, pp. 7–53.

- ^ Lawrence, Geoffrey; et al., eds. (1946), "Session 62: February 19, 1946", The Trial of German Major War Criminals: Sitting at Nuremberg, Germany, 7, London: HM Stationery Office, p. 111, http://www.nizkor.org/hweb/imt/tgmwc/tgmwc-07/tgmwc-07-62-01.shtml.

- ^ http://history.sandiego.edu/gen/WW2Timeline/camps.html

- ^ Staff Writer (August 21, 1944), "Vernichtungslager", Time magazine (August 21, 1944), http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,932705,00.html, retrieved May 12, 2010.

- ^ a b c d Czerwinska, Ewa (August 19, 2008), "Listy z piekła", Kurier Lubelski, http://www.kurierlubelski.pl/module-dzial-viewpub-tid-9-pid-61237.html.

- ^ "List of archives", Majdanek State Museum, 2006, http://www.majdanek.pl/articles.php?acid=19.

- ^ Witos, A., et al., eds. (1944), Commique of the Polish-Soviet Extraordinary Commission for Investigating the Crimes Committed by the Germans in the Majdanek Extermination Camp in Lublin, Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, http://www.jewishgen.org/ForgottenCamps/Camps/MajdanekReport.html#1.

- ^ United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington.

- ^ Staff Writer (November 15, 2005), "Survivors find hidden treasures", News 24, news24.com, http://www.news24.com/News24/World/News/0,,2-10-1462_1834817,00.html.

- ^ a b c Roberts, Sam (November 4, 2005), "Treasures Emerge From Field of the Dead at Maidanek", New York Times, http://www.nytimes.com/2005/11/04/international/europe/04poland.html?_r=2&pagewanted=1&oref=slogin.

- ^ Staff writer (April 20, 2006), "Musical to be staged at concentration camp", The Jerusalem Post, jpost.com, http://fr.jpost.com/servlet/Satellite?cid=1143498885645&pagename=JPost%2FJPArticle%2FPrinter.

- ^ "Brand in voormalig Pools concentratiekamp". Radio Netherlands Worldwide. 11 August 2010.

- ^ Nuremberg Trial. 19 Feb 1946. Evidence submitted by Polish-Soviet Extraordinary Commission's report on Maidanek. http://avalon.law.yale.edu/imt/02-19-46.asp

- ^ Delayed Impact: the Holocaust and the Canadian Jewish Community (2002). Bialystok, Franklin. page 25. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=TEOzC2c9gmYC&lpg=PA25&dq=Alfr%C3%A9d%20Wetzler%203%20million&pg=PA25#v=onepage&q=%22raymond%20arthur%20davies,%20an%20independent%20journalist%20based%20in%20Moscow%20and%20on%20the%20Congress%20payroll%22&f=false.

- ^ Canadian Jewish Congress Charities Committee National Archives - Collection Guide: http://www.cjccc.ca/national_archives/archives/arcguideD.htm

- ^ Delayed Impact: the Holocaust and the Canadian Jewish Community (2002). Bialystok, Franklin. page 25. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=TEOzC2c9gmYC&lpg=PA25&dq=Alfr%C3%A9d%20Wetzler%203%20million&pg=PA25#v=snippet&q=%22I%20do%20wish%20%5Bto%5D%20stress%20that%20Majdanek%20where%20one%20million%20Jews%20and%20half%20a%20million%20others%20%5Bwere%5D%20killed%22&f=false

- ^ Delayed Impact: the Holocaust and the Canadian Jewish Community (2002). Bialystok, Franklin. page 25. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=TEOzC2c9gmYC&lpg=PA25&dq=Alfr%C3%A9d%20Wetzler%203%20million&pg=PA25#v=snippet&q=%22You%20can%20tell%20America%20that%20at%20least%20three%20million%20%5BPolish%5D%20Jews%20%5Bwere%5D%20killed%20of%20whom%20at%20least%20a%20third%20were%20killed%20in%20Majdanek%22%22&f=false

See also

- List of Nazi-German concentration camps

- Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics

- Research Materials: Max Planck Society Archive

- Shark Island, German South West Africa

External links

The Holocaust in Poland - Main article: The Holocaust

- Related articles by country:

- Belarus

- Estonia

- Latvia

- Lithuania

- Norway

- Russia

- Ukraine

Camps, ghettos and operations Camps ExterminationMass shootings Ghettos - List of 267 Jewish ghettos set up in German-occupied Poland (1939–1942)

- Będzin

- Białystok

- Brest

- Częstochowa

- Grodno

- Kraków

- Lvov (Lwów)

- Łódź

- Lubartów

- Lublin

- Międzyrzec Podlaski

- Radom

- Sosnowiec

- Warsaw

Other atrocities Perpetrators, participants, organizations, and collaborators Major perpetrators Organizers- Josef Bühler

- Eichmann

- Eicke

- Ludwig Fischer

- Hans Frank

- Globocnik

- Glücks

- Greiser

- Himmler

- Hermann Höfle

- Fritz Katzmann

- Wilhelm Koppe

- Friedrich-Wilhelm Krüger

- Kutschera

- Erwin Lambert

- Ernst Lerch

- Oswald Pohl

- Reinefarth

- Scherner

- Seyss-Inquart · Sporrenberg

- Streckenbach

- Thomalla

- Otto Wächter

- Wisliceny

Camp command- Aumeier

- Richard Baer

- Boger

- Braunsteiner

- Eberl

- Kurt Franz

- Karl Frenzel

- Karl Fritzsch

- Göth

- Grabner

- Hartjenstein

- Hering

- Höss

- Hössler

- Josef Kramer

- Liebehenschel

- Maria Mandel

- Matthes

- Michel

- Johann Niemann

- Oberhauser

- Reichleitner

- Heinrich Schwarz

- Stangl

- Gustav Wagner

- Christian Wirth

Gas chamber executioners- Erich Bauer

- Bolender

- Hackenholt

- Klehr

- Hans Koch

- Herbert Lange

Ghetto command- Wolfgang Birkner

- Blobel

- Felix Landau

- Schaper

- Schöngarth

- von Woyrsch

Personnel Camp guardsBy campOrganizations Collaborators JewishEstonian, Latvian,

Lithuanian, Belarusian

and UkrainianOther nationalities- Arajs Kommando

- Ukrainian Auxiliary Police

- Ukrainian collaboration

- Lithuanian Security Police

- Trawniki

- Ypatingasis būrys

- Pieter Menten

Resistance: Judenrat, victims, documentation and technical Organizations Uprisings Leaders Judenrat - Jewish Ghetto Police

- Adam Czerniaków

- Mordechai Chaim Rumkowski

Victim Lists Ghettos- Kraków

- Łódź

- Lvov (Lwów)

- Warsaw

Camps- Auschwitz

- Bełżec

- Chełmno

- Gross-Rosen

- Izbica

- Kraków-Płaszów

- Majdanek

- Sobibor

- Soldau

- Stutthof

- Trawniki

- Treblinka

Documentation Nazi sources- Auschwitz Album

- Frank Memorandum

- Höcker Album

- Höfle Telegram

- Katzmann Report

- Korherr Report

- Nisko Plan

- Posen speeches

- Special Prosecution Book-Poland

- Stroop Report

- Wannsee Conference

Witness accounts- Graebe affidavit

- Gerstein Report

- Vrba-Wetzler report

- Witold's report

ConcealmentTechnical and Logistics - Identification in camps

- Gas chamber

- Gas van

- Holocaust train

- Human medical experimentation

- Zyklon B

Aftermath, trials and commemoration Aftermath Trials West German trials- Frankfurt Auschwitz Trials

- Treblinka trials

Polish, East German, and Soviet trialsMemorials Righteous among the Nations - Polish Righteous among the Nations

- Rescue of Jews by Poles during the Holocaust

- Albert Battel

- Hermann Friedrich Graebe

- Andrey Sheptytsky

- Oskar Schindler

Categories:- Majdanek concentration camp

- 1941 in Poland

- 1942 in Poland

- 1943 in Poland

- 1944 in Poland

- Nazi concentration camps

- World War II sites

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.