- Jesus

-

This article is about Jesus of Nazareth. For other uses, see Jesus (disambiguation).

Jesus

Jesus as Good Shepherd (stained glass at St John's Ashfield).Born 7–2 BC/BCE[1]

Bethlehem, Judaea, Roman Empire (traditional);

Nazareth, Galilee (modern critical scholarship)[2]Died 30–36 AD/CE[3][4][5][6][7]

Calvary, Judaea, Roman Empire (according to the New Testament, he rose on the third day after his death.)Cause of death Crucifixion Resting place Traditionally and temporarily, a garden tomb in Jerusalem[8] Nationality Israelite Ethnicity Jewish Home town Nazareth, Galilee, Roman Empire Religion Judaism Parents Father: God (Christian view)

virginal conception (Islamic view)

Joseph (other views)

Mother: Mary

Adoptive father: JosephJesus of Nazareth (

/ˈdʒiːzəs/; 7–2 BC/BCE to 30–36 AD/CE), commonly referred to as Jesus Christ or simply as Jesus or Christ, is the central figure of Christianity. Most Christian denominations venerate him as God the Son incarnated and believe that he rose from the dead after being crucified.[9][10] The principal sources of information regarding Jesus are the four canonical gospels,[11] and most biblical scholars find them useful for reconstructing Jesus' life and teachings.[12][13][14][15] Scholars have correlated the New Testament accounts with non-Christian historical records to arrive at an estimated chronology for the major episodes in the life of Jesus.[16][5] [3][17]

/ˈdʒiːzəs/; 7–2 BC/BCE to 30–36 AD/CE), commonly referred to as Jesus Christ or simply as Jesus or Christ, is the central figure of Christianity. Most Christian denominations venerate him as God the Son incarnated and believe that he rose from the dead after being crucified.[9][10] The principal sources of information regarding Jesus are the four canonical gospels,[11] and most biblical scholars find them useful for reconstructing Jesus' life and teachings.[12][13][14][15] Scholars have correlated the New Testament accounts with non-Christian historical records to arrive at an estimated chronology for the major episodes in the life of Jesus.[16][5] [3][17]Most critical historians agree that Jesus was a Galilean Jewish Rabbi who was regarded as a teacher and healer in Judaea,[18] that he was baptized by John the Baptist, and that he was crucified in Jerusalem on the orders of the Roman Prefect, Pontius Pilate, on the charge of sedition against the Roman Empire.[19] Critical Biblical scholars and historians have offered competing descriptions of Jesus as a self-described Messiah, as the leader of an apocalyptic movement, as an itinerant sage, as a charismatic healer, and as the founder of an independent religious movement. Most contemporary scholars of the historical Jesus consider him to have been an independent, charismatic founder of a Jewish restoration movement, anticipating a future apocalypse.[20] Other prominent scholars, however, contend that Jesus' "Kingdom of God" meant radical personal and social transformation instead of a future apocalypse.[20]

Christians traditionally believe that Jesus was born of a virgin,[10] performed miracles,[10] founded the Church, rose from the dead, and ascended into heaven,[10] from which he will return.[10] The majority of Christians worship Jesus as the incarnation of God the Son, and "the Second Person of the Blessed Trinity".[21] A few Christian groups, however, reject Trinitarianism, wholly or partly, believing it to be non-scriptural.[21][22] Most Christian scholars today present Jesus as the awaited Messiah promised in the Old Testament and as God,[23] arguing that he fulfilled many Messianic prophecies of the Old Testament.[24]

Judaism rejects assertions that Jesus was the awaited Messiah, arguing that he did not fulfill the Messianic prophecies in the Tanakh.[25] In Islam, Jesus (in Arabic: عيسى in Islamic usage, commonly transliterated as Isa) is considered one of God's important prophets,[26][27] a bringer of scripture, and the product of a virgin birth, but not the victim of crucifixion.[28] Islam and the Bahá'í Faith use the title "Messiah" for Jesus,[29][30] but do not teach that he was God incarnate.

Etymology of name

A series of articles on

Jesus Christ and Christianity Gospel harmony · Virgin birth

Circumcision · Baptism

Ministry · Miracles · Parables

Death · Burial · Resurrection

Ascension · Heavenly Session

Second Coming

Christology · Names and titles

Relics · Active obedienceJesus and Islam Islamic views of Mary · Disciples of Jesus in Islam

Islamic view of Jesus' death · The Second coming · The Mahdi · Jesus in the end of time · The fight with the Anti-ChristCultural-historical background Perspectives on Jesus Biblical

Christian · Lutheran

Jewish · Islamic

Ahmadi · ScientologyJesus and history Historicity · Chronology

Historical reliability of the Gospels

Historical Jesus

Comparative mythology

Jesus myth theory

Jesus in the TalmudJesus in culture "Jesus" is a transliteration, occurring in a number of languages and based on the Latin Iesus, of the Greek Ἰησοῦς (Iēsoûs), itself a hellenization of the Hebrew יְהוֹשֻׁעַ (Yĕhōšuă‘, Joshua) or Hebrew-Aramaic יֵשׁוּעַ (Yēšûă‘), both meaning "Yahweh delivers" or "Yahweh rescues".[31][32]

The etymology of the name Jesus is generally expressed by Christians as "God's salvation" usually expressed as "Yahweh saves",[33][34][35] "Yahweh is salvation"[36][37] and at times as "Jehovah is salvation".[38] The name Jesus appears to have been in use in Judaea at the time of the birth of Jesus.[38][39] Philo's reference (Mutatione Nominum item 121) indicates that the etymology of Joshua was known outside Judaea at the time.[40]

In the New Testament, in Luke 1:26-33, the angel Gabriel tells Mary to name her child "Jesus", and in Matthew 1:21 an angel tells Joseph to name the child "Jesus". The statement in Matthew 1:21 "you are to give him the name Jesus, because he will save his people from their sins" associates salvific attributes to the name Jesus in Christian theology.[41][42]

"Christ" (

/ˈkraɪst/) is derived from the Greek Χριστός (Khrīstos), meaning "the anointed" or "the anointed one", a translation of the Hebrew מָשִׁיחַ (Māšîaḥ), usually transliterated into English as "Messiah" (

/ˈkraɪst/) is derived from the Greek Χριστός (Khrīstos), meaning "the anointed" or "the anointed one", a translation of the Hebrew מָשִׁיחַ (Māšîaḥ), usually transliterated into English as "Messiah" ( /mɨˈsaɪ.ə/).[43][44] In the Septuagint version of the Hebrew Bible (written well over a century before the time of Jesus), the word "Christ" (Χριστός) was used to translate into Greek the Hebrew word "Messiah" ( מָשִׁיחַ).[45] In Matthew 16:16, the apostle Peter's profession "You are the Christ" identifies Jesus as the Messiah.[46] In postbiblical usage, "Christ" became viewed as a name, one part of "Jesus Christ", but originally it was a title ("Jesus the Anointed").[47]

/mɨˈsaɪ.ə/).[43][44] In the Septuagint version of the Hebrew Bible (written well over a century before the time of Jesus), the word "Christ" (Χριστός) was used to translate into Greek the Hebrew word "Messiah" ( מָשִׁיחַ).[45] In Matthew 16:16, the apostle Peter's profession "You are the Christ" identifies Jesus as the Messiah.[46] In postbiblical usage, "Christ" became viewed as a name, one part of "Jesus Christ", but originally it was a title ("Jesus the Anointed").[47]Chronology

Main article: Chronology of JesusAlthough a few scholars have questioned the existence of Jesus as an actual historical figure,[48] most scholars involved with historical Jesus research believe his existence, but not the supernatural claims associated with him, can be established using documentary and other evidence.[49][50][51][52][53][54] As discussed in the sections immediately below, the estimation of the year of death of Jesus places his lifespan around the beginning of the 1st century AD/CE, in the geographic region of Roman Judaea.[55][56][57][58][59] The New Testament also refers to the Sea of Galilee which is about 75 miles north of Jerusalem.[60]

Roman involvement in Judaea began around 63 BC/BCE and by 6 AD/CE Judaea had become a Roman province.[61] From 26-37 AD/CE Pontius Pilate was the governor of Roman Judaea.[62] In this time period, although Roman Judaea was strategically positioned between Asia and Africa, it was not viewed as a critically important province by the Romans.[63][64] The Romans were highly tolerant of other religions and allowed the local populations such as the Jews to practice their own faiths.[61]

Year of birth estimates

Two independent approaches have been used to estimate the year of the birth of Jesus, one by analyzing the Nativity accounts in the Gospels of Luke and Matthew along with other historical data, the other by working backwards from the estimation of the start of the ministry of Jesus, as also discussed in the section below.[5][17]

In its Nativity account, the Gospel of Matthew associates the birth of Jesus with the reign of Herod the Great, who is generally believed to have died around 4 BC/BCE.[17][65] Matthew 2:1 states that: "Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judaea in the days of Herod the king" and Luke 1:5 mentions the reign of Herod shortly before the birth of Jesus.[17] Matthew also suggests that Jesus may have been as much as two years old at the time of the visit of the Magi and hence even older at the time of Herod's death.[66] But the author of Luke also describes the birth as taking place during the first census of the Roman provinces of Syria and Iudaea, which is generally believed to have occurred in 6 AD/CE.[67] Most scholars generally assume a date of birth between 6 and 4 BC/BCE.[68] Other scholars assume that Jesus was born sometime between 7–2 BC/BCE.[69][70][71][72][73]

The year of birth of Jesus has also been estimated in a manner that is independent of the Nativity accounts, by using information in the Gospel of John to work backwards from the statement in Luke 3:23 that Jesus was "about 30 years of age" at the start of his ministry.[3][5] As discussed in the section below, by combining information from John 2:13 and John 2:20 with the writings of Josephus, it has been estimated that around 27-29 AD/CE, Jesus was "about thirty years of age".[74][75] Some scholars thus estimate the year 28 AD/CE to be roughly the 32nd birthday of Jesus and the birth year of Jesus to be around 6-4 BC/BCE.[3][5][76]

However, the common Gregorian calendar method for numbering years, in which the current year is 2011, is based on the decision of a monk Dionysius in the six century, to count the years from a point of reference (namely, Jesus’ birth) which he placed sometime between 2 BC and 1 AD.[77] Although Christian feasts related to the Nativity have had specific dates (e.g. December 25 for Christmas) there is no historical evidence for the exact day or month of the birth of Jesus.[78][79][80]

Years of ministry estimates

There have been different approaches to estimating the date of the start of the ministry of Jesus.[3][74][75][81] One approach, based on combining information from the Gospel of Luke with historical data about Emperor Tiberius yields a date around 28-29 AD/CE, while a second independent approach based on statements in the Gospel of John along with historical information from Josephus about the Temple in Jerusalem leads to a date around 27-29 AD/CE.[5][74][75][82][83][84] A third method uses the date of the death of John the Baptist and the marriage of Herod Antipas to Herodias based on the writings of Josephus, and correlates it to Matthew 14:4.[85][86][87]

The estimation of the date based on the Gospel of Luke relies on the statement in Luke 3:1-2 that the ministry of John the Baptist which preceded that of Jesus began "in the fifteenth year of the reign of Tiberius Caesar".[74] Given that Tiberius began his reign in 14 AD/CE, this yields a date about 28-29 AD/CE.[3][74][76][88][89]

The estimation of the date based on the Gospel of John uses the statements in John 2:13 that Jesus went to the Temple in Jerusalem around the start of his ministry and in John 2:20 that "Forty and six years was this temple in building" at that time.[5][74] According to Josephus (Ant 15.380) the temple reconstruction was started by Herod the Great in the 15th-18th year of his reign at about the time that Augustus arrived in Syria (Ant 15.354).[3][74][90][91] Temple expansion and reconstruction was ongoing, and it was in constant reconstruction until it was destroyed in 70 AD/CE by the Romans.[92] Given that it took 46 years of construction, the Temple visit in the Gospel of John has been estimated at around 27-29 AD/CE.[5][74][82][83][84][93]

Although both the gospels and Josephus refer to Herod Antipas killing John the Baptist, they differ on the details, e.g. whether this act was a consequence of the marriage of Herod Antipas and Herodias, as indicated in Matthew 14:4, or a pre-emptive measure by Herod which possibly took place before the marriage, as Josephus suggests in Ant 18.5.2.[94][95][96][97] The exact year of the marriage of Herod Antipas and Herodias is subject to debate among scholars.[86] In his analysis of Herod's life, Harold Hoehner estimates that John the Baptist's imprisonment probably occurred around AD 30-31.[98] The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia estimates the death of the Baptist to have occurred about AD 31-32.[87] The death of John the Baptist relates to the end of the major Galilean ministry of Jesus, just before the half way point in the gospel narratives, before the start of Jesus' final journey to Jerusalem through Judea.[99][100][100][101]

Luke 3:23 states that at the start of his ministry Jesus was "about 30 years of age", but the other Gospels do not mention a specific age. However, in John 8:57 the Jews exclaimed to Jesus: "Thou art not yet fifty years old, and hast thou seen Abraham?" suggesting that he was much less than 50 years old during his ministry.[5] The length of the ministry is subject to debate, based on the fact that the Synoptic Gospels mention only one passover during Jesus' ministry, often interpreted as implying that the ministry lasted approximately one year, whereas the Gospel of John records multiple passovers, implying that his ministry may have lasted at least three years.[3][5][102][103]

Year of death estimates

A 1466 copy of Antiquities of the Jews

A 1466 copy of Antiquities of the Jews

A number of approaches have been used to estimate the year of the death of Jesus, including information from the Canonical Gospels, the chronology of the life of Paul the Apostle in the New Testament correlated with historical events, as well as different astronomical models, as discussed below.

All four canonical Gospels report that Jesus was crucified in Calvary during the prefecture of Pontius Pilate, the Roman prefect who governed Judaea from 26 to 36 AD/CE. The late 1st century Jewish historian Josephus,[55] writing in Antiquities of the Jews (c. 93 AD/CE), and the early 2nd century Roman historian Tacitus,[56] writing in The Annals (c. 116 AD/CE), also state that Pilate ordered the execution of Jesus, though each writer gives him the title of "procurator" instead of prefect.[57]

The estimation of the date of the conversion of Paul places the death of Jesus before this conversion, which is estimated at around 33-36 AD/CE.[4][104][105] (Also see the estimation of the start of Jesus' ministry as a few years before this date above). The estimation of the year of Paul's conversion relies on a series of calculations working backwards from the well established date of his trial before Gallio in Achaea Greece (Acts 18:12-17) around 51-52 AD/CE, the meeting of Priscilla and Aquila which were expelled from Rome about 49 AD/CE and the 14-year period before returning to Jerusalem in Galatians 2:1.[4][104][105] The remaining period is generally accounted for by Paul's missions (at times with Barnabas) such as those in Acts 11:25-26 and 2 Corinthians 11:23-33, resulting in the 33-36 AD/CE estimate.[4][104][105]

For centuries, astronomers and scientists have used diverse computational methods to estimate the date of crucifixion, Isaac Newton being one of the first cases.[58] Newton's method relied on the relative visibility of the crescent of the new moon and he suggested the date as Friday, April 23, 34 AD/CE.[106] In 1990 astronomer Bradley E. Schaefer computed the date as Friday, April 3, 33 AD/CE.[107] In 1991, John Pratt stated that Newton's method was sound, but included a minor error at the end. Pratt suggested the year 33 AD/CE as the answer.[58] Using the completely different approach of a lunar eclipse model, Humphreys and Waddington arrived at the conclusion that Friday, April 3, 33 AD/CE was the date of the crucifixion.[59][108][109]

Life and teachings in the New Testament

See also: Life of Jesus in the New TestamentAlthough the four canonical gospels, Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, are the main sources for the biography of Jesus’ life, other parts of the New Testament, such as the Pauline epistles which were likely written decades before them, also include references to key episodes in his life such as the Last Supper, as in 1 Corinthians 11:23-26.[110][111][112] The Acts of the Apostles (10:37-38 and 19:4) refers to the early ministry of Jesus and its anticipation by John the Baptist.[113][114] And Acts 1:1-11 says more about the Ascension episode (also mentioned in 1 Timothy 3:16) than the canonical gospels.[115][116]

The four gospel accounts

Three of the four canonical gospels, namely Matthew, Mark, and Luke, are known as the Synoptic Gospels, from the Greek σύν (syn "together") and ὄψις (opsis "view"). These three gospels display a high degree of similarity in content, narrative arrangement, language and paragraph structures.[117] The presentation in the fourth canonical Gospel, i.e. the John, differs from these three in that it has more of a thematic nature rather than a narrative format.[118][119] And scholars generally agree that it is impossible to find any direct literary relationship between the synoptic gospels and the Gospel of John.[118]

However, in general, the authors of the New Testament showed little interest in an absolute chronology of Jesus or in synchronizing the episodes of his life with the secular history of the age.[120] The gospels were primarily written as theological documents in the context of early Christianity with the chronological timelines as a secondary consideration.[121] One manifestation of the gospels being theological documents rather than historical chronicles is that they devote about one third of their text to just seven days, namely the last week of the life of Jesus in Jerusalem.[122]

Although the gospels do not provide enough details to satisfy the demands of modern historians regarding exact dates, it is possible to draw from them a general picture of the life story of Jesus.[120][121][123] However, as stated in John 21:25 the gospels do not claim to provide an exhaustive list of the events in the life of Jesus.[124]

Gospel sources, similarities and differences

See also: Gospel harmony and Historical reliability of the GospelsScholars have debated the sources for the gospels for millennia, and have proposed various hypotheses of how the synoptic gospels were written and how they influenced each other, going back to the Augustinian hypothesis in the 5th century.[125] In the 20th and 21st centuries hypotheses such as the two-source, four-source, Farrer or the Markan priority hypothesis have been debated.[125][126][127] Each hypothesis assumes a specific order in which the gospels were written, or that other as yet unknown and hypothetical documents such as the Q source or the M source influenced various gospels in various ways. Each hypotheses has had support among some scholars, while problems with and weaknesses in it have been pointed out by opponents.[125][126][127][128]

Since the 2nd century attempts have been made to harmonize the gospel accounts into a single narrative; Tatian's Diatesseron perhaps being the first harmony and other works such as Augustine' book Harmony of the Gospels followed.[129][130] A number of different approaches to gospel harmony have been proposed in the 20th century, but no single and unique harmony can be constructed.[131] While some scholars argue that combining the four gospel stories into one story is tantamount to creating a fifth story different from each original, others see the gospels as blending together to give an overall and comprehensive picture of Jesus' teaching and ministry.[130][132][133][134] Although there are differences in specific temporal sequences, and in the parables and miracles listed in each gospel, the flow of the key events such as Baptism, Transfiguration and Crucifixion and interactions with people such as the Apostles are shared among the gospel narratives.[120][121][135][136]

Key elements and the five major milestones

The five major milestones in the gospel narrative of the life of Jesus are his Baptism, Transfiguration, Crucifixion, Resurrection and Ascension.[137][138][139] These are usually bracketed by two other episodes: his Nativity at the beginning and the sending of the Paraclete at the end.[137][139] The gospel accounts of the teachings of Jesus are often presented in terms of specific categories involving his "works and words", e.g. his ministry, parables and miracles.[140][141]

The gospels include a number discourses by Jesus on specific occasions, e.g. the Sermon on the Mount or the Farewell Discourse, and also include over 30 parables, spread throughout the narrative, often with themes that relate to the sermons.[142] Parables represent a major component of the teachings of Jesus in the gospels, forming approximately one third of his recorded teachings, and John 14:10 positions them as the revelations of God the Father.[143][144] The gospel episodes that include descriptions of the miracle of Jesus also often include teachings, providing an intertwining of his "words and works" in the gospels.[141][145]

-

Resurrection & Appearances

Genealogy and Nativity

The accounts of the genealogy and Nativity of Jesus in the New Testament appear only in the Gospel of Luke and the Gospel of Matthew. While there are documents outside of the New Testament which are more or less contemporary with Jesus and the gospels, many shed no light on the more biographical aspects of his life and these two gospel accounts remain the main sources of information on the genealogy and Nativity.[146][147]

Genealogy

Main article: Genealogy of JesusMatthew begins his gospel in 1:1 with the genealogy of Jesus, and presents it before the account of the birth of Jesus, while Luke discusses the genealogy in chapter 3, after the Baptism of Jesus in Luke 3:22 when the voice from Heaven addresses Jesus and identifies him as the Son of God.[148] At that point Luke traces Jesus' ancestry through Adam to God.[148]

While Luke traces the genealogy upwards towards Adam and God, Matthew traces it downwards towards Jesus.[149] Both gospels state that Jesus was begotten not by Joseph, but by God.[150] Both accounts trace Joseph back to King David and from there to Abraham. These lists are identical between Abraham and David (except for one), but they differ almost completely between David and Joseph.[151][152] Matthew gives Jacob as Joseph’s father and Luke says Joseph was the son of Heli. Attempts at explaining the differences between the genealogies have varied in nature, e.g. that Luke traces the genealogy through Mary while Matthew traces it through Joseph; or that Jacob and Heli were both fathers of Joseph, one being the legal father, after the death of Joseph's actual father—but there is no scholarly agreement on a resolution for the differences.[153][154][155]

Nativity

Main article: Nativity of JesusThe Nativity is a prominent element in the Gospel of Luke, comprises over 10% of the text, and is three times the length of the nativity text in Matthew.[156] Luke's account takes place mostly before the birth of Jesus and centers on Mary, while Matthew's takes place mostly after the birth of Jesus and centers on Joseph.[157][158][159] According to Luke and Matthew, Jesus was born to Joseph and Mary, his betrothed, in Bethlehem. Both support the doctrine of the Virgin Birth in which Jesus was miraculously conceived in his mother's womb by the Holy Spirit, when his mother was still a virgin.[160][161][162][163]

Luke is the only Gospel to provide an account of the birth of John the Baptist, and uses it to draw parallels between the births of John and Jesus.[164] Luke relates the two births in the visitation of Mary to Elizabeth[156] and further connects the two births by stating that Mary and Elizabeth are cousins.[165] In Luke 1:31-38 Mary learns from the angel Gabriel that she will conceive and bear a child called Jesus through the action of the Holy Spirit. When Mary is due to give birth, she and Joseph travel from Nazareth to Joseph's ancestral home in Bethlehem to register in the census of Quirinius. In Luke 2:1-7. Mary gives birth to Jesus and, having found no place in the inn, places the newborn in a manger. An angel visits the shepherds and sends them to adore the child in Luke 2:22. After presenting Jesus at the Temple, Joseph and Mary return home to Nazareth.[158][166]

The nativity account in chapters 1 and 2 of the Gospel of Matthew appears to differ from Luke in implying that Jesus and his family are already living in Bethlehem.[167] However, Matthew does not state that Joseph lived in Bethlehem prior to the birth of Jesus.[168] Following his betrothal to Mary, Joseph is troubled in Matthew 1:19-20 because Mary is pregnant, but in the first of Joseph's three dreams an angel assures him not be afraid to take Mary as his wife, because her child was conceived by the Holy Spirit.[169] In Matthew 1:1-12, the Wise Men or Magi bring gifts to the young Jesus after following a star which they believe was a sign that the King of the Jews had been born. King Herod hears of Jesus' birth from the Wise Men and tries to kill him by massacring all the male children in Bethlehem under the age of two (the Massacre of the Innocents).[170] Before the massacre, Joseph is warned by an angel in his dream and the family flees to Egypt and remains there until Herod's death, after which they leave Egypt and settle in Nazareth to avoid living under the authority of Herod's son and successor Archelaus.[169][171]

Early life and profession

See also: Return of young Jesus to NazarethIn the Gospels of Luke and Matthew, Jesus’ childhood home is identified as the town of Nazareth in Galilee. Joseph, husband of Mary, appears in descriptions of Jesus’ childhood and no mention is made of him thereafter.[172] The New Testament books of Matthew, Mark, and Galatians mention Jesus’ brothers and sisters, but the Greek word adelphos in these verses, has also been translated as brother or kinsman.[173]

Luke 2:41–52 includes an incident in the childhood of Jesus, where he was found teaching in the temple by his parents after being lost. The Finding in the Temple is the sole event between Jesus’ infancy and baptism mentioned in any of the canonical Gospels.

In Mark 6:3 Jesus is called a tekton (τέκτων in Greek), usually understood to mean carpenter. Matthew 13:55 says he was the son of a tekton.[44]:170 Tekton has been traditionally translated into English as "carpenter", but it is a rather general word (from the same root that leads to "technical" and "technology") that could cover makers of objects in various materials, even builders.[174][175]

Beyond the New Testament accounts, the specific association of the profession of Jesus with woodworking is a constant in the traditions of the 1st and 2nd centuries and Justin Martyr (d. ca. 165) wrote that Jesus made yokes and ploughs.[176]

Baptism and temptation

In the gospels, the accounts of the Baptism of Jesus are always preceded by information about John the Baptist and his ministry.[135][178][179] In these accounts, John was preaching for penance and repentance for the remission of sins and encouraged the giving of alms to the poor (as in Luke 3:11) as he baptized people in the area of the River Jordan around Perea about the time of the commencement of the ministry of Jesus. The Gospel of John (1:28) specifies "Bethany beyond the Jordan", i.e. Bethabara in Perea, when it initially refers to it and later John 3:23 refers to further baptisms in Ænon "because there was much water there".[180][181]

The four gospels are not the only references to John's ministry around the River Jordan. In Acts 10:37-38, Apostle Peter refers to how the ministry of Jesus followed "the baptism which John preached".[114] In the Antiquities of the Jews (18.5.2) 1st century historian Flavius Josephus also wrote about John the Baptist and his eventual death in Perea.[182][183]

In the gospels, John had been foretelling (as in Luke 3:16) of the arrival of a someone "mightier than I".[184][185] Apostle Paul also refers to this anticipation by John in Acts 19:4.[113] In Matthew 3:14, upon meeting Jesus, the Baptist states: "I need to be baptized by you." However, Jesus persuades John to baptize him nonetheless.[186] In the baptismal scene, after Jesus emerges from the water, the sky opens and a voice from Heaven states: "This is my beloved Son with whom I am well pleased". The Holy Spirit then descends upon Jesus as a dove in Matthew 3:13-17, Mark 1:9-11, Luke 3:21-23.[184][185][186] In John 1:29-33 rather than a direct narrative, the Baptist bears witness to the episode.[185][187] This is one of two cases in the gospels where a voice from Heaven calls Jesus "Son", the other being in the Transfiguration of Jesus episode.[188][189]

After the baptism, the Synoptic gospels proceed to describe the Temptation of Jesus, but John 1:35-37 narrates the first encounter between Jesus and two of his future disciples, who were then disciples of John the Baptist.[190][191] In this narrative, the next day the Baptist sees Jesus again and calls him the Lamb of God and the "two disciples heard him speak, and they followed Jesus".[192][193][194] One of the disciples is named Andrew, but the other remains unnamed, and Raymond E. Brown raises the question of his being the author of the Gospel of John himself.[187][195] In the Gospel of John, the disciples follow Jesus thereafter, and bring other disciples to him, and Acts 18:24-19:6 portrays the disciples of John as eventually merging with the followers of Jesus.[187][190]

The Temptation of Jesus is narrated in the three Synoptic gospels after his baptism.[191][196] In these accounts, as in Matthew 4:1-11 and Luke 4:1-13, Jesus goes to the desert for forty days to fast. While there, Satan appears to him and tempts him in various ways, e.g. asking Jesus to show signs that he is the Son of God by turning stone to bread, or offering Jesus worldly rewards in exchange for worship.[191][197] Jesus rejects every temptation and when Satan leaves, angels appear and minister to Jesus.[191][196][197]

Ministry

Main articles: Ministry of Jesus and Twelve ApostlesLuke 3:23 states that Jesus was "about 30 years of age" at the start of his ministry.[3][5] The date of the start of his ministry has been estimated at around 27-29 AD/CE, based on independent approaches which combine separate gospel accounts with other historical data.[3][5][74][75][82][83][84] The end of his ministry is estimated to be in the range 30-36 AD/CE.[3][4][5][6]

The three Synoptic gospels refer to just one passover during his ministry, while the Gospel of John refers to three passovers, suggesting a period of about three years.[178][198] However, the Synoptic gospels do not require a ministry that lasted only one year, and scholars such as Köstenberger state that the Gospel of John simply provides a more detailed account.[135][178][199]

The gospel accounts place the beginning of Jesus' ministry in the countryside of Judaea, near the River Jordan.[179] Jesus' ministry begins with his Baptism by John the Baptist (Matthew 3, Luke 3), and ends with the Last Supper with his disciples (Matthew 26, Luke 22) in Jerusalem.[178][179] The gospels present John the Baptist's ministry as the pre-cursor to that of Jesus and the Baptism as marking the beginning of Jesus' ministry, after which Jesus travels, preaches and performs miracles.[135][178][179]

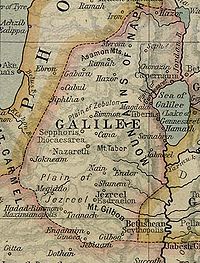

A 1923 map of Galilee around 50 AD/CE. Nazareth is towards the center.

A 1923 map of Galilee around 50 AD/CE. Nazareth is towards the center.

The Early Galilean ministry begins when Jesus goes back to Galilee from the Judaean desert after rebuffing the temptation of Satan.[200] In this early period Jesus preaches around Galilee and in Matthew 4:18-20 his first disciples encounter him, begin to travel with him and eventually form the core of the early Church.[179][201] This period includes the Sermon on the Mount, one of the major discourses of Jesus.[201][202]

The Major Galilean ministry which begins in Matthew 8 refers to activities up to the death of John the Baptist. It includes the Calming the storm and a number of other miracles and parables, as well as the Mission Discourse in which Jesus instructs the twelve apostles who are named in Matthew 10:2-3 to carry no belongings as they travel from city to city and preach.[203][204]

The Final Galilean ministry includes the Feeding the 5000 and Walking on water episodes, both in Matthew 14.[205][206] The end of this period (as Matthew 16 and Mark 8 end) marks a turning point is the ministry of Jesus with the dual episodes of Confession of Peter and the Transfiguration - which begins his Later Judaean ministry as he starts his final journey to Jerusalem through Judaea.[207][208][209][210]

As Jesus travels towards Jerusalem, in the Later Perean ministry, about one third the way down from the Sea of Galilee along the Jordan, he returns to the area where he was baptized, and in John 10:40-42 "many people believed in him beyond the Jordan", saying "all things whatsoever John spake of this man were true".[211][212][213] This period of ministry includes the Discourse on the Church in which Jesus anticipates a future community of followers, and explains the role of his apostles in leading it.[214][215] At the end of this period, the Gospel of John includes the Raising of Lazarus episode.[216]

The Final ministry in Jerusalem is sometimes called the Passion Week and begins with the Jesus' triumphal entry into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday.[216] In that week Jesus drives the money changers from the Temple, and Judas bargains to betray him. This period includes the Olivet Discourse and the Second Coming Prophecy and culminates in the Last Supper, at the end of which Jesus prepares his disciples for his departure in the Farewell discourse. The accounts of the ministry of Jesus generally end with the Last Supper.[135][216][217] However, some authors also consider the period between the Resurrection and the Ascension part of the ministry of Jesus.[218]

Teachings and preachings

Main articles: Sermon on the Mount and Parables of JesusSee also: Sermon on the Plain, Five Discourses of Matthew, Farewell Discourse, and Olivet DiscourseIn the New Testament the teachings of Jesus are presented in terms of his "words and works".[140][141] The words of Jesus include a number of sermons, as well as parables that appear throughout the narrative of the Synoptic Gospels (the gospel of John includes no parables). The works include the miracles and other acts performed during his ministry.[141] Although the Canonical Gospels are the major source of the teachings of Jesus, the Pauline epistles, which were likely written decades before the gospels, provide some of the earliest written accounts of the teachings of Jesus.[110]

The New Testament does not present the teachings of Jesus as merely his own preachings, but equates the words of Jesus with divine revelation, with John the Baptist stating in John 3:34: "he whom God hath sent speaketh the words of God" and Jesus stating in John 7:16: "My teaching is not mine, but his that sent me" and again re-asserting that in John 14:10: "the words that I say unto you I speak not from myself: but the Father abiding in me doeth his works."[144][219] In Matthew 11:27 Jesus claims divine knowledge, stating: "No one knows the Son except the Father and no one knows the Father except the Son", asserting the mutual knowledge he has with the Father.[220][221]

The gospels include a number of discourses by Jesus on specific occasions, such as the Farewell discourse delivered after the Last Supper, the night before his crucifixion.[222] Although some of the teachings of Jesus are reported as taking place within the formal atmosphere of a synagogue (e.g. in Matthew 4:23) many of the discourses are more like conversations than formal lectures.[223]

The Gospel of Matthew has a structured set of sermons, often grouped as the Five Discourses of Matthew which present many of the key teachings of Jesus.[224][225] Each of the five discourses has some parallel passages in the Gospel of Mark or the Gospel of Luke.[226] The five discourses in Matthew begin with the Sermon on the Mount, which encapsulates many of the moral teaching of Jesus and which is one of the best known and most quoted elements of the New Testament.[202][223] The Sermon on the Mount includes the Beatitudes which describe the character of the people of the Kingdom of God, expressed as "blessings".[227] The Beatitudes focus on love and humility rather than force and exaction and echo the key ideals of Jesus' teachings on spirituality and compassion.[228][229][230] The other discourses in Matthew include the Missionary Discourse in Matthew 10 and the Discourse on the Church in Matthew 18, providing instructions to the disciples and laying the foundation of the codes of conduct for the anticipated community of followers.[215][231][232]

Parables represent a major component of the teachings of Jesus in the gospels, the approximately thirty parables forming about one third of his recorded teachings.[142][143] The parables may appear within longer sermons, as well as other places within the narrative.[223] Jesus' parables are seemingly simple and memorable stories, often with imagery, and each conveys a teaching which usually relates the physical world to the spiritual world.[233][234]

The gospel episodes that include descriptions of the miracle of Jesus also often include teachings, providing an intertwining of his "words and works" in the gospels.[141][145] Many of the miracles in the gospels teach the importance of faith, for instance in Cleansing ten lepers and Daughter of Jairus the beneficiaries are told that they were healed due to their faith.[235][236]

Proclamation as Christ and Transfiguration

Main articles: Confession of Peter and Transfiguration of JesusAt about the middle of each of the three Synoptic Gospels, two related episodes mark a turning point in the narrative: the Confession of Peter and the Transfiguration of Jesus.[207][208] These episodes begin in Caesarea Philippi just north of the Sea of Galilee at the beginning of the final journey to Jerusalem which ends in the Passion and Resurrection of Jesus.[237] These episodes mark the beginnings of the gradual disclosure of the identity of Jesus to his disciples; and his prediction of his own suffering and death.[188][189][207][208][237]

Peter's Confession begins as a dialogue between Jesus and his disciples in Matthew 16:13, Mark 8:27 and Luke 9:18. Jesus asks his disciples: But who do you say that I am? Simon Peter answers him: You are the Christ, the Son of the living God.[237][238][239] In Matthew 16:17 Jesus blesses Peter for his answer, and states: "flesh and blood hath not revealed it unto thee, but my Father who is in heaven." In blessing Peter, Jesus not only accepts the titles Christ and Son of God which Peter attributes to him, but declares the proclamation a divine revelation by stating that his Father in Heaven had revealed it to Peter.[240] In this assertion, by endorsing both titles as divine revelation, Jesus unequivocally declares himself to be both Christ and the Son of God.[240][241]

The account of the Transfiguration of Jesus appears in Matthew 17:1-9, Mark 9:2-8, Luke 9:28-36.[188][189][189][208] Jesus takes Peter and two other apostles with him and goes up to a mountain, which is not named. Once on the mountain, Matthew (17:2) states that Jesus "was transfigured before them; his face shining as the sun, and his garments became white as the light." At that point the prophets Elijah and Moses appear and Jesus begins to talk to them.[188] Luke is specific in describing Jesus in a state of glory, with Luke 9:32 referring to "they saw his glory".[242] A bright cloud appears around them, and a voice from the cloud states: "This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased; listen to him".[188]

The Transfiguration not only supports the identity of Jesus as the Son of God (as in his Baptism), but the statement "listen to him", identifies him as the messenger and mouth-piece of God.[243] The significance is enhanced by the presence of Elijah and Moses, for it indicates to the apostles that Jesus is the voice of God, and instead of Elijah or Moses, he should be listened to, by virtue of his filial relationship with God.[243] 2 Peter 1:16-18, echoes the same message: at the Transfiguration God assigns to Jesus a special "honor and glory" and it is the turning point at which God exalts Jesus above all other powers in creation.[244]

At the end of both episodes, as in some other pericopes in the New Testament such as miracles, Jesus tells his disciples not to repeat to others, what they had seen - the command at times interpreted in the context of the theory of the Messianic Secret.[245] At the end of the Transfiguration episode, Jesus commands the disciples to silence about it "until the Son of man be risen from the dead", relating the Transfiguration to the Resurrection episode.[246][247][248]

Final week: betrayal, arrest, trial, and death

The description of the last week of the life of Jesus (often called the Passion week) occupies about one third of the narrative in the Canonical gospels.[122] The narrative for that week starts by a description of the final entry into Jerusalem, and ends with his crucifixion.[135][216]

The last week in Jerusalem is the conclusion of the journey which Jesus had started in Galilee through Perea and Judea.[216] Just before the account of the final entry of Jesus into Jerusalem, the Gospel of John includes the Raising of Lazarus episode, which builds the tension between Jesus and the authorities. At the beginning of the week as Jesus enters Jerusalem, he is greeted by the cheering crowds, adding to that tension.[216]

During the week of his "final ministry in Jerusalem", Jesus visits the Temple, and has a conflict with the money changers about their use of the Temple for commercial purposes. This is followed by a debate with the priests and the elder in which his authority is questioned. One of his disciples, Judas Iscariot, decides to betray Jesus for thirty pieces of silver.[250]

Towards the end of the week, Jesus has the Last Supper with his disciples, during which he institutes the Eucharist, and prepares them for his departure in the Farewell Discourse. After the supper, Jesus is betrayed with a kiss while he is in agony in the garden, and is arrested. After his arrest, Jesus is abandoned by most of his disciples, and Peter denies him three times, as Jesus had predicted during the Last Supper.[251][252]

Jesus is first questioned by the Sanhedrin, and is then tried by Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor of Judea. During these trials Jesus says very little, and is mostly silent. After the scourging of Jesus, and his mocking as the King of the Jews Pilate orders the crucifixion.[253][254]

Thus the final week that begins with his entry into Jerusalem, concludes with his crucifixion and burial on that Friday, as described in the next 5 sub-sections. The New Testament accounts then describe the resurrection of Jesus three days later, on the Sunday following his death.

Final entry into Jerusalem

Main articles: Triumphal entry into Jerusalem, Cleansing of the Temple, and Bargain of JudasIn the four Canonical Gospels, Jesus' Triumphal entry into Jerusalem takes place at the beginning of the last week of his life, a few days before the Last Supper, marking the beginning of the Passion narrative.[255][258][259][260][261] While at Bethany Jesus sent two disciples to retrieve a donkey that had been tied up but never ridden and rode it into Jerusalem, with Mark and John stating Sunday, Matthew Monday, and Luke not specifying the day.[255][258][259] As Jesus rode into Jerusalem the people there lay down their cloaks in front of him, and also lay down small branches of trees and sang part of Psalm 118: 25-26.[255][257][258][259]

In the three Synoptic Gospels, entry into Jerusalem is followed by the Cleansing of the Temple episode, in which Jesus expels the money changers from the Temple, accusing them of turning the Temple to a den of thieves through their commercial activities. This is the only account of Jesus using physical force in any of the Gospels.[220][262][263] John 2:13-16 includes a similar narrative much earlier, and scholars debate if these refer to the same episode.[220][262][263] The synoptics include a number of well known parables and sermons such as the Widow's mite and the Second Coming Prophecy during the week that follows.[258][259]

In that week, the synoptics also narrate conflicts between Jesus and the elders of the Jews, in episodes such as the Authority of Jesus Questioned and the Woes of the Pharisees in which Jesus criticizes their hypocrisy.[258][259] Judas Iscariot, one of the twelve apostles approaches the Jewish elders and performs the "Bargain of Judas" in which he accepts to betray Jesus and hand him over to the elders.[264][250][265] Matthew specifies the price as thirty silver coins.[250]

Last Supper

Main article: Last SupperSee also: Jesus predicts his betrayal, Denial of Peter, and Last Supper in Christian artIn the New Testament, the Last Supper is the final meal that Jesus shares with his twelve apostles in Jerusalem before his crucifixion. The Last Supper is mentioned in all four Canonical Gospels, and Paul's First Epistle to the Corinthians (11:23-26), which was likely written before the Gospels, also refers to it.[111][112][266][267]

Jesus with the Eucharist (detail), by Juan de Juanes, mid-late 16th century.

Jesus with the Eucharist (detail), by Juan de Juanes, mid-late 16th century.

In all four gospels, during the meal, Jesus predicts that one of his Apostles will betray him.[268] Jesus is described as reiterating, despite each Apostle's assertion that he would not betray Jesus, that the betrayer would be one of those who were present. In Matthew 26:23-25 and John 13:26-27 Judas is specifically singled out as the traitor.[111][112][268]

In Matthew 26:26-29, Mark 14:22-25, Luke 22:19-20 Jesus takes bread, breaks it and gives it to the disciples, saying: "This is my body which is given for you". In 1 Corinthians 11:23-26 Apostle Paul provides the theological underpinnings for the use of the Eucharist, stating: "This cup is the new covenant in my blood; do this, whenever you drink it, in remembrance of me."[111][269] Although the Gospel of John does not include a description of the bread and wine ritual during the Last Supper, most scholars agree that John 6:58-59 (the Bread of Life Discourse) has a Eucharistic nature and resonates with the "words of institution" used in the Synoptic Gospels and the Pauline writings on the Last Supper.[270]

In all four Gospels Jesus predicts that Peter will deny knowledge of him, stating that Peter will disown him three times before the rooster crows the next morning. The synoptics mention that after the arrest of Jesus Peter denied knowing him three times, but after the third denial, heard the rooster crow and recalled the prediction as Jesus turned to look at him. Peter then began to cry bitterly.[271][272]

The Gospel of John provides the only account of Jesus washing his disciples' feet before the meal.[273] John's Gospel also includes a long sermon by Jesus, preparing his disciples (now without Judas) for his departure. Chapters 14-17 of the Gospel of John are known as the Farewell discourse given by Jesus, and are a rich source of Christological content.[222][274]

Agony in the Garden, betrayal and arrest

Main articles: Agony in the Garden, Kiss of Judas, and Arrest of JesusSee also: Holy HourIn Matthew 26:36-46, Mark 14:32-42, Luke 22:39-46 and John 18:1, immediately after the Last Supper, Jesus takes a walk to pray, Matthew and Mark identifying this place of prayer as Garden of Gethsemane.[275][276]

Jesus is accompanied by Peter, John and James the Greater, whom he asks to "remain here and keep watch with me." He moves "a stone's throw away" from them, where he feels overwhelming sadness and says "My Father, if it is possible, let this cup pass me by. Nevertheless, let it be as you, not I, would have it."[276] Only the Gospel of Luke mentions the details of the sweat of blood of Jesus and the visitation of the angel who comforts Jesus as he accepts the will of the Father. Returning to the disciples after prayer, he finds them asleep and in Matthew 26:40 he asks Peter: "So, could you men not keep watch with me for an hour?"[276]

While in the Garden, Judas appears, accompanied by a crowd that includes the Jewish priests and elders and people with weapons. Judas gives Jesus a kiss to identify him to the crowd who then arrests Jesus.[276][277] One of Jesus' disciples tries to stop them and uses a sword to cut off the ear of one of the men in the crowd.[276][277] Luke states that Jesus miraculously healed the wound and John and Matthew state that Jesus criticized the violent act, insisting that his disciples should not resist his arrest. In Matthew 26:52 Jesus makes the well known statement: all who live by the sword, shall die by the sword.[276][277]

Prior to the arrest, in Matthew 26:31 Jesus tells the disciples: "All ye shall be offended in me this night" and in 32 that: "But after I am raised up, I will go before you into Galilee." After his arrest, Jesus' disciples go into hiding.[276]

-

Last Supper & Farewell

Trials by the Sanhedrin, Herod and Pilate

Main articles: Sanhedrin trial of Jesus, Pilate's Court, Jesus at Herod's Court, and Crown of ThornsSee also: Jesus, King of the Jews and What is truth?In the narrative of the four Canonical Gospels after the betrayal and arrest of Jesus, he is taken to the Sanhedrin, a Jewish judicial body.[278] Jesus is tried by the Sanhedrin, mocked and beaten and is condemned for making claims of being the Son of God.[277][279][280] He is then taken to Pontius Pilate and the Jewish elders ask Pilate to judge and condemn Jesus—accusing him of claiming to be the King of the Jews.[280] After questioning, with few replies provided by Jesus, Pilate publicly declares that he finds Jesus innocent, but the crowd insists on punishment. Pilate then orders Jesus' crucifixion.[277][279][280][281] Although the Gospel accounts vary with respect to various details, they agree on the general character and overall structure of the trials of Jesus.[281]

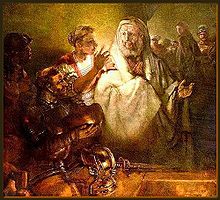

Jesus in the upper right hand corner, his hands bound behind, is being tried at the high priest's house and turns to look at Peter, in Rembrandt's 1660 depiction of Peter's Denial.[282]

Jesus in the upper right hand corner, his hands bound behind, is being tried at the high priest's house and turns to look at Peter, in Rembrandt's 1660 depiction of Peter's Denial.[282]

In, Matthew 26:57, Mark 14:53 and Luke 22:54 Jesus was taken to the high priest's house where he was mocked and beaten that night. The next day, early in the morning, the chief priests and scribes gathered together and lead Jesus away into their council.[277][279][280][283] In John 18:12-14, however, Jesus is first taken to Annas, the father-in-law of Caiaphas, and then to Caiaphas.[277][279][280] In all four Gospel accounts the trial of Jesus is interleaved with the Denial of Peter narrative, where Apostle Peter who has followed Jesus denies knowing him three times, at which point the rooster crows as predicted by Jesus during the Last Supper.[279][284]

In the Gospel accounts Jesus speaks very little, mounts no defense and gives very infrequent and indirect answers to the questions of the priests, prompting an officer to slap him. In Matthew 26:62 the lack of response from Jesus prompts the high priest to ask him: "Answerest thou nothing?"[277][279][280][285] Mark 14:55-59 states that the chief priests had arranged false witness against Jesus, but the witnesses did not agree together. In Mark 14:61 the high priest then asked Jesus: "Are you the Christ, the Son of the Blessed? And Jesus said, I am" at which point the high priest tore his own robe in anger and accused Jesus of blasphemy. In 22:70 when asked: "Are you then the Son of God?" Jesus answers: "You say that I am" affirming the title Son of God.[286] At that point the priests say: "What further need have we of witness? for we ourselves have heard from his own mouth" and decide to condemn Jesus.[277][279][280] In Matthew 27:3-5 Judas, who has watched the trial from a distance, is distraught by his betrayal of Jesus, and attempts to return the thirty pieces of silver he had received for betraying Jesus. The priests tell him that his guilt is of his own account. Judas throws the money into the temple, and then leaves and hangs himself.[276][277]

Taking Jesus to Pilate's Court, the Jewish elders ask Pontius Pilate to judge and condemn Jesus—accusing him of claiming to be the King of the Jews.[280] In Luke 23:7-15 (the only Gospel account of this episode), Pilate realizes that Jesus is a Galilean, and is thus under the jurisdiction of Herod Antipas.[287][288][289][290][291] Pilate sends Jesus to Herod to be tried.[292] However, Jesus says almost nothing in response to Herod's questions, or the continuing accusations of the chief priests and the scribes. Herod and his soldiers mock Jesus, put a gorgeous robe on him, as the King of the Jews, and sent him back to Pilate.[287] Pilate then calls together the Jewish elders, and says that he has "found no fault in this man."[292]

The use of the term king is central in the discussion between Jesus and Pilate. In John 18:36 Jesus states: "My kingdom is not of this world", but does not directly deny being the King of the Jews.[293][294] And when in John 19:12 Pilate seeks to release Jesus, the priests object and say: "Every one that makes himself a king speaks against Caesar . . . We have no king but Caesar."[295] Pilate then writes "Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews" as a sign (abbreviated as INRI in depictions) to be affixed to the cross of Jesus.[296]

In Matthew 27:19 Pilate's wife, tormented by a dream, urges Pilate not to have anything to do with Jesus, and Pilate publicly washes his hands of responsibility, yet orders the crucifixion in response to the demands of the crowd. The trial by Pilate is followed by the flagellation episode, the soldiers mock Jesus as the King of Jews by putting a purple robe (that signifies royal status) on him, place a Crown of Thorns on his head, and beat and mistreat him in Matthew 27:29-30, Mark 15:17-19 and John 19:2-3.[254] Jesus is then sent to Calvary for crucifixion.[277][279][280]

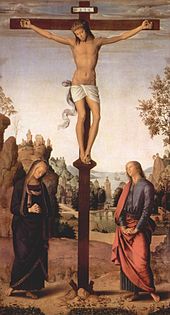

Crucifixion and burial

Main article: Crucifixion of JesusSee also: Sayings of Jesus on the cross, Crucifixion eclipse, and Entombment of ChristJesus' crucifixion is described in all four Canonical gospels, and is attested to by other sources of that age (e.g. Josephus and Tacitus), and is regarded as an historical event.[297][298][299]

After the trials, Jesus made his way to Calvary (the path is traditionally called via Dolorosa) and the three Synoptic Gospels indicate that he was assisted by Simon of Cyrene, the Romans compelling him to do so.[300][301] In Luke 23:27-28 Jesus tells the women in multitude of people following him not to cry for him but for themselves and their children.[300] Once at Calvary (Golgotha), Jesus was offered wine mixed with gall to drink — usually offered as a form of painkiller. Matthew's and Mark's Gospels state that he refused this.[300][301]

The soldiers then crucified Jesus and cast lots for his clothes. Above Jesus' head on the cross was the inscription King of the Jews, and the soldiers and those passing by mocked him about the title. Jesus was crucified between two convicted thieves, one of whom rebuked Jesus, while the other defended him.[300][302] Each gospel has its own account of Jesus' last words, comprising the seven last sayings on the cross.[303][304][305] In John 19:26-27 Jesus entrusts his mother to the disciple he loved and in Luke 23:34 he states: "Father, forgive them; for they know not what they do", usually interpreted as his forgiveness of the Roman soldiers and the others involved.[303][306][307][308]

In the three Synoptic Gospels, various supernatural events accompany the crucifixion, including darkness of the sky, an earthquake, and (in Matthew) the resurrection of saints.[301] The tearing of the temple veil, upon the death of Jesus, is referenced in the synoptic.[301] The Roman soldiers did not break Jesus' legs, as they did to the other two men crucified (breaking the legs hastened the crucifixion process), as Jesus was dead already. One of the soldiers pierced the side of Jesus with a lance and water flowed out.[302] In Mark 13:59, impressed by the events the Roman centurion calls Jesus the Son of God.[300][301][309][310]

Following Jesus' death on Friday, Joseph of Arimathea asked the permission of Pilate to remove the body. The body was removed from the cross, was wrapped in a clean cloth and buried in a new rock-hewn tomb, with the assistance of Nicodemus.[300] In Matthew 27:62-66 the Jews go to Pilate the day after the crucifixion and ask for guards for the tomb and also seal the tomb with a stone as well as the guard, to be sure the body remains there.[300][311][312]

Resurrection and ascension

See also: Empty tomb, Great Commission, Second Coming, Resurrection of Jesus in Christian art, and Ascension of Jesus in Christian artThe New Testament accounts of the resurrection and ascension of Jesus, state that the first day of the week after the crucifixion (typically interpreted as a Sunday), his followers encounter him risen from the dead, after his tomb is discovered to be empty.[115][116][313][314] The resurrected Jesus appears to them that day and a number of times thereafter, delivers sermons and commissions them, before ascending to Heaven. Two of the Canonical gospels (Luke and Mark) include a brief mention of the Ascension, but the main references to it are elsewhere in the New Testament.[115][116][314]

In the four Canonical Gospels, when the tomb of Jesus is discovered empty, in Matthew 28:5, Mark 16:5, Luke 24:4 and John 20:12 his resurrection is announced and explained to the followers who arrive there early in the morning by either one or two beings (either men or angels) dressed in bright robes who appear in or near the tomb.[115][116][314] The gospel accounts vary as to who arrived at the tomb first, but they are women and are instructed by the risen Jesus to inform the other disciples. All four accounts include Mary Magdalene and three include Mary the mother of Jesus. The accounts of Mark 16:9, John 20:15 indicate that Jesus appeared to the Magdalene first, and Luke 16:9 states that she was among the Myrrhbearers who informed the disciples about the resurrection.[115][116][314] In Matthew 28:11-15, to explain the empty tomb, the Jewish elders bribe the soldiers who had guarded the tomb to spread the rumor that Jesus' disciples took his body.[116]

After the discovery of the empty tomb, the Gospels indicate that Jesus made a series of appearances to the disciples.[115][116] These include the well known Doubting Thomas episode, where Thomas did not believe the resurrection until he was invited to put his finger into the holes made by the wounds in Jesus' hands and side; and the Road to Emmaus appearance where Jesus meets two disciples. The catch of 153 fish appearance includes a miracle at the Sea of Galilee, and thereafter Jesus encourages Apostle Peter to serve his followers.[115][116][314]

The final post-resurrection appearance in the Gospel accounts is when Jesus ascends to Heaven where he remains with God the Father and the Holy Spirit.[115][116] The Canonical Gospels include only brief mentions of the Ascension of Jesus, Luke 24:51 states that Jesus "was carried up into heaven". The ascension account is further elaborated in Acts 1:1-11 and mentioned 1 Timothy 3:16. In Acts 1:1-9, forty days after the resurrection, as the disciples look on, "he was taken up; and a cloud received him out of their sight." 1 Peter 3:22 describes Jesus as being on "the right hand of God, having gone into heaven".[115][116]

The Acts of the Apostles also contain "post-ascension" appearances by Jesus. These include the vision by Stephen just before his death in Acts 7:55,[315] and the road to Damascus episode in which Apostle Paul is converted to Christianity.[316][317] The instruction given to Ananias in Damascus in Acts 9:10-18 to heal Paul is the last reported conversation with Jesus in the Bible until the Book of Revelation was written.[316][317]

-

Angel at empty tomb

Matthew 28:5 -

Ascension

Acts 1:9

Title attributions

Main article: Names and titles of Jesus in the New TestamentThe New Testament attributes a wide range of titles to Jesus by the authors of the Gospels, by Jesus himself, a voice from Heaven (often assumed to be God) during the Baptism and Transfiguration, as well as various groups of people such as the disciples, and even demons throughout the narrative.[254][318] The emphasis on the titles used in each of the four canonical Gospels gives a different emphasis to the portrayal of Jesus in that Gospel.[132][319][320]

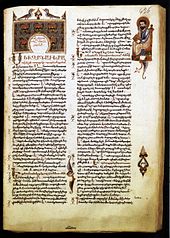

First page of a 14th century Gospel of Mark, applying 2 titles to Jesus: "The beginning of the gospel of Jesus Christ, the Son of God".

First page of a 14th century Gospel of Mark, applying 2 titles to Jesus: "The beginning of the gospel of Jesus Christ, the Son of God".

Two of the key titles used for Jesus in the New Testament are Christ and Son of God.[47][321] The opening words in Mark 1:1 attribute both Christ and Son of God as titles, reaffirming the second title again in Mark 1:11.[322] The Gospel of Matthew also begins in 1:1 with the Christ title and reaffirms it in Matthew 1:16.[322] Beyond the declarations by the Gospel writers, titles are attributed in the narrative. The statement by Apostle Peter in Matthew 16:16 ("you are the Christ, the Son of the living God") is a key turning point in the Gospel narrative, where Jesus is proclaimed as both Christ and Son of God by his followers and he accepts both titles.[238] The immediate declaration by Jesus that the titles were revealed to Peter by "my Father who is in Heaven" not only endorses both titles as divine revelation but includes a separate assertion of sonship by Jesus within the same statement.[240]

In the Gospel of John, Jesus refers to himself as the Son of God far more frequently than in the Synoptic Gospels.[323] In a number of other episodes Jesus claims sonship by referring to the Father, e.g. in Luke 2:49 when he is found in the temple a young Jesus calls the temple "my Father's house", just as he does later in John 2:16 in the Cleansing of the Temple episode.[220] However, scholars still debate if Jesus was making a claim to divinity in these statements.[324][325][326] In John 11:27 Martha tells Jesus "you are the Christ, the Son of God", signifying that both titles were later used (yet considered distinct) in the narrative.[327] While the Gospel of John frequently uses the Son of God title, the Gospel of Luke emphasizes Jesus as a prophet.[328]

One of the most frequent titles for Jesus in the New Testament is the Greek word Kyrios (κύριος) which may mean God, Lord or master and is used to refers to him over 700 times.[329][330] In everyday Aramaic, Mari was a very respectful form of polite address, well above "Teacher" and similar to Rabbi. In Greek this has at times been translated as Kyrios.[331] The Rabbi title is used in several New Testament episodes to refer to Jesus, but more often in the Gospel of John than elsewhere and does not appear in the Gospel of Luke at all.[332] Although Jesus accepts this title in the narrative, in Matthew 23:1-8 he rejected the title of Rabbi for his disciples, saying: "But be not ye called Rabbi".[332][333][334]

Some New Testament scholars argue that Jesus claimed to be God through his frequent use of "I am" (Ego eimi in Greek and Qui est in Latin). This term is used by Jesus in the Gospel of John on several occasions to refer to himself, seven times with specific titles.[335][336] It is used in the Gospel of John both with or without a predicate.[336] The seven uses with a predicate that have resulted in titles for Jesus are: Bread of Life, Light of the World, the Door, the Good Shepherd, the Resurrection of Life, the Way, the Truth and the Life, the Vine.[335] It is also used without a predicate, which is very unusual in Greek and Christologists usually interpret it as God's own self-declaration.[336] In John 8:24 Jesus states: "unless you believe that I am you will die in your sins" and in John 8:59 the crowd attempts to stone Jesus in response to his statement that "Before Abraham was, I am".[336] However, many modern scholars believe that Jesus never made a claim to divinity.[337][338] John Hick says that this "is a point of broad agreement among New Testament scholars".[339]

The Gospel of John opens by identifying Jesus as the divine Logos in John 1:1-18. The Greek term Logos (λόγος) is often translated as "the Word" in English.[340] The identification of Jesus as the Logos which became Incarnate appears only at the beginning of the Gospel of John and the term Logos is used only in two other Johannine passages: 1 John 1:1 and Revelation 19:13.[341][342][343][344] John's Logos statements build on each other: the statement that the Logos existed "at the beginning" asserts that as Logos Jesus was an eternal being like God; that the Logos was "with God" asserts the distinction of Jesus from God; and Logos "was God" states the unity of Jesus with God.[273][342][345][346]

Some authors have suggested that other titles applied to Jesus in the New Testament had meanings in the 1st century quite different from those meanings ascribed today, e.g. “Son of David” is found elsewhere in Jewish tradition to refer to the heir to the throne.[347]

Historical views

Existence of Jesus

Main articles: Historicity of Jesus and Chronology of JesusSee also: Josephus on Jesus and Tacitus on Jesus A 1640 edition of the works of Josephus, a 1st century non-Christian historian who referred to Jesus.[348][349]

A 1640 edition of the works of Josephus, a 1st century non-Christian historian who referred to Jesus.[348][349]

The Christian gospels were written primarily as theological documents rather than historical chronicles.[121][122] However, the question of the existence of Jesus as a historical figure should be distinguished from discussions about the historicity of specific episodes in the gospels, the chronology they present, or theological issues regarding his divinity.[350] A number of historical non-Christian documents, such as Jewish and Greco-Roman sources, have been used in historical analyses of the existence of Jesus.[348] Most critical historians agree that Jesus existed and regard events such as his baptism and his crucifixion as historical.[19][351][352][353]

Robert E. Van Voorst states that the idea of the non-historicity of the existence of Jesus has always been controversial, and has consistently failed to convince scholars of many disciplines, and that classical historians, as well as biblical scholars now regard it as effectively refuted.[354] Walter P. Weaver, among others, states that the denial of Jesus’ existence has never convinced any large number of people, in or out of technical circles.[352][353][355]

Separate non-Christian sources used to establish the historical existence of Jesus include the works of 1st century Roman historians Flavius Josephus and Tacitus.[348][356] Josephus scholar Louis H. Feldman has stated that few have doubted the genuineness of Josephus' reference.[349][357] Bart D. Ehrman states that the existence of Jesus and his crucifixion by the Romans is attested to by a wide range of sources, including Josephus and Tacitus.[358]

In antiquity, the existence of Jesus was never denied, even by those who opposed Christianity.[120] Although a very small number of modern scholars argue that Jesus never existed, that view is a distinct minority and most scholars consider theories that Jesus' existence was a Christian invention as implausible.[350][359][360]

Language, race and appearance

Jesus grew up in Galilee and much of his ministry took place there.[361] The languages spoken in Galilee and Judea during the 1st century AD/CE include Aramaic, Hebrew and Greek, with Aramaic being the predominant language.[362][363] Most scholars agree that during the early part of 1st century AD/CE Aramaic was the mother tongue of virtually all women in Galilee and Judae.[364] Most scholars support the theory that Jesus spoke Aramaic and that he may have also spoken Hebrew and Greek.[362][363][365][366]

The New Testament includes no description of the physical appearance of Jesus before his death and its narrative is generally indifferent to racial appearances and does not refer to the features of the people it discusses.[369][370][371] The Synoptic Gospels include the account of the Transfiguration of Jesus during which he was glorified with "his face shining as the sun" but do not provide details of his everyday appearance.[189][208] The Book of Revelation describes the features of a glorified Jesus in a vision (1:13-16), but the vision refers to Jesus in heavenly form, after his death.[372][373] Old Testament references about the coming Messiah have been projected forward to form conjectures about the appearance of Jesus on theological, rather than historical grounds; e.g. Isaiah 53:2 which refers to the coming Messiah as "no beauty that we should desire him" and Psalm 45:2-3 which describes him as "fairer than the children of men", often interpreted as a description of his physical appearance.[374][375][376][377]

Despite the lack of direct biblical or historical references, from the 2nd century, various theories about the race of Jesus were advanced, e.g. by Justin Martyr based on arguments on the genealogy of Jesus.[378] These arguments have been subject to debate for centuries among modern scholars.[378] Another suggestion by anti-Christian pagan author Celsus (who was likely aware of the gospel texts, and mocked them) that Jesus' father was a Roman soldier named Pantera drew responses from Origen who considered it a fabricated story, and scholars continue to view it as having no historical basis.[379][380][381][382][383][384]

By the Middle Ages a number of documents, generally of unknown origin, were circulating with details of the appearance of Jesus, e.g. a forged letter by Publius Lentulus, the Governor of Judea, to the Roman Senate, which according to most scholars dates to around the year 1300 and was composed to compensate for the lack of any physical description of Jesus in the Bible.[370] Other spurious references include the Archko Volume and the letter of Pontius Pilate to Tiberius Caesar, the descriptions in which were most likely composed in the Middle Ages.[385][386][387]

By the 19th century theories that Jesus was European, and in particular Aryan, were developed and later appealed to those who wanted nothing Jewish about Jesus, e.g. Nazi theologians.[371][388] These theories usually also include the reasoning that Jesus was Aryan because Galilee was an Aryan region, but have not gained scholarly acceptance.[371][389] By the 20th century, theories had also been proposed that Jesus was of black African descent, e.g. based on the argument that Mary his mother was a descendant of black Jews.[390] By the 21st century the race of Jesus was being addressed on television, e.g. a 2001 BBC program that suggested specific physical characteristics for him.[391][392] In the 21st century, the race of Jesus also had a cultural component in cinematic portrayals, e.g. actor James Caviezel was made-up to look semitic as he portrayed Jesus.[393][394]

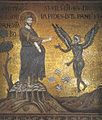

Depictions of Jesus

Main article: Depictions of JesusDespite the lack of biblical references or historical records, for two millennia a wide range of depictions of Jesus have appeared, often influenced by cultural settings, political circumstances and theological contexts.[367][368][370] As in other Christian art, the earliest depictions date to the late 2nd or early 3rd century, and survivors are primarily found in the Catacombs of Rome.[395] In these early depictions, which use popular rather than elite Graeco-Roman styles, Jesus is usually shown as a youthful figure without a beard and with curly hair, often with different features from the other men in the scenes, such as his disciples or the Romans.[369]

Healing the paralytic, a very early depiction of Jesus, c. 235 Dura-Europos church

Healing the paralytic, a very early depiction of Jesus, c. 235 Dura-Europos church

Although some images exist at the synagogue at Dura-Europos, Judaism forbade images, and there is no record of its influence on the depictions of Jesus.[367] Christian depictions of the 3rd and 4th centuries typically focused on New Testament scenes of healings and other miracles.[395] Following the conversion of Constantine in the 4th century, Christian art found many wealthy donors and flourished.[395] In this period Jesus began to have more mature features, and was shown with a beard.[369] A new development at this time was the depiction of Jesus without a narrative context, but just as a figure by himself.[369]

By the 5th century depictions of the Passion began to appear, perhaps reflecting a change in the theological focus of the early Church.[395] The 6th century Rabbula Gospels includes some of the earliest surviving images of the crucifixion and resurrection.[395] By the 6th century the bearded depiction of Jesus had become standard in the East, though the West, especially in northern Europe, continued to mix bearded and unbearded depictions for several centuries. The depiction with a longish face, long straight brown hair parted in the middle, and almond shaped eyes shows consistency from the 6th century to the present. Various legends developed which were believed to authenticate the historical accuracy of the standard depiction, such as the image of Edessa and later the Veil of Veronica.[369] Partly to aid recognition of the scenes, narrative depictions of the Life of Christ focused increasingly on the events celebrated in the major feasts of the church calendar, and the events of the Passion, neglecting the miracles and other events of Jesus's public ministry, except for the raising of Lazarus, where the mummy-like wrapped body was shown standing upright, giving an unmistakable visual signature. A cruciform halo was worn only by Jesus (and the other persons of the Trinity), while plain halos distinguished Mary, the Apostles and other saints, helping the viewer to read increasingly populated scenes.

The Byzantine Iconoclasm acted as a barrier to developments in the East, but by the 9th century art was permitted again.[367] The Transfiguration of Jesus was a major theme in the East and every Eastern Orthodox monk who had trained in icon painting had to prove his craft by painting an icon of the Transfiguration.[396] However, while Western depictions aim for proportion, in the Eastern icons the abolition of perspective and alterations in the size and proportion of an image aim to reaches beyond man's earthly dwellings.[397]

The 13th century witnessed a turning point in the portrayal of the powerful Kyrios image of Jesus as a wonder worker in the West, as the Franciscans began to emphasize the humility of Jesus both at his birth and his death via the nativity scene as well as the crucifixion.[398][399][400] The Franciscans approached both ends of this spectrum of emotions and as the joys of the Nativity of were added to the agony of crucifixion a whole new range of emotions were ushered in, with wide ranging cultural impact on the image of Jesus for centuries thereafter.[398][400][401][402]

The Renaissance brought forth a number of artists who focused on the depictions of Jesus and after Giotto, Fra Angelico and others systematically developed uncluttered images that focused on the depiction of Jesus with an ideal human beauty.[367] Leonardo da Vinci's Last Supper which is considered the first work of High Renaissance art due to its high level of harmony became well known for depicting Jesus surrounded by varying emotions of the individual apostles at the announcement of the betrayal.[403][404] Meanwhile, the Protestant Reformation, especially in its first decades, violently objected to almost all public religious images as idolaterous, and vast numbers were destroyed.

By the end of the 19th century, new reports of miraculous images of Jesus had appeared and continue to receive significant attention, e.g. Secondo Pia's 1898 photograph of the Shroud of Turin, one of the most controversial artifacts in history, which during its May 2010 exposition it was visited by over 2 million people.[405][406][407] Another 20th century depiction of Jesus, namely the Divine Mercy image based on Faustina Kowalska's reported vision has over 100 million followers.[408][409] The first cinematic portrayal of Jesus was in the 1897 film La Passion du Christ produced in Paris, which lasted 5 minutes.[410][411] Thereafter cinematic portrayals have continued to show Jesus with a beard in the standard western depiction that resembles traditional images.[412]

Analysis of the gospels