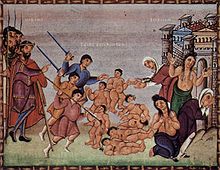

- Massacre of the Innocents

-

The Massacre of the Innocents is an episode of infanticide by the King of Judea, Herod the Great. According to the Gospel of Matthew[1] Herod orders the execution of all young male children in the village of Bethlehem, so as to avoid the loss of his throne to a newborn King of the Jews whose birth has been announced to him by the Magi. The incident, like others in Matthew, is described as the fulfillment of a passage in the Old Testament read as prophecy,[2] in this case a reading of Jeremiah: "Then was fulfilled that which was spoken through Jeremiah the prophet, saying, A voice was heard in Ramah, Weeping and great mourning, Rachel weeping for her children."[3]

The infants, known in the Church as the Holy Innocents, have been claimed as the first Christian martyrs. Some accounts number them at more than ten thousand, but more conservative estimates put their number in the low dozens.[4]. Historians generally view the event as non-historical.[5]

Contents

Biblical account

In Matthew's account, magi from the east go to Judea in search of the newborn king of the Jews, having "seen his star in the east". The King, Herod the Great, directs them to Bethlehem, and asks them to let him know who this king is when they find him. They find Jesus and honor him, but an angel tells them not to alert Herod, and they return home by another way.

The Massacre of the Innocents is at Matthew 2:16-18, although the preceding verses form the context:

When [the Magi] had gone, an angel of the Lord appeared to Joseph in a dream. Get up, he said, take the child and his mother and escape to Egypt. Stay there until I tell you, for Herod is going to search for the child to kill him. So he got up, took the child and his mother during the night and left for Egypt, where he stayed until the death of Herod. And so was fulfilled what the Lord had said through the prophet: "Out of Egypt I called my son."[6] When Herod realised that he had been outwitted by the Magi, he was furious, and he gave orders to kill all the boys in Bethlehem and its vicinity who were two years old and under, in accordance with the time he had learned from the Magi. Then what was said through the prophet Jeremiah was fulfilled: "A voice is heard in Ramah, weeping and great mourning, Rachel weeping for her children and refusing to be comforted, because they are no more."[3]

Matthew's purpose is to present Jesus as the Messiah, and the Massacre of the Innocents as the fulfillment of passages in Hosea, referring to the exodus, and Jeremiah, to the Babylonian exile.[7][8] Raymond Brown sees the story as patterned on the Exodus story of the killing of the Hebrew firstborn by Pharaoh and the birth of Moses.[9]

Historicity

The single account of the Massacre comes in the Gospel of Matthew. The massacre is not mentioned in Luke's gospel or by any contemporaneous historians, or by the later Roman Jewish historian, Josephus.

The majority of Herod biographers, followed by biblical scholars, hold that the massacre is "legend and not historical".[10] Geza Vermes and E. P. Sanders regard the story as creative hagiography.[11] Robert Eisenman argues that the story may have its origins in Herod's murder of his own sons, an act which made a deep impression at the time and was recorded by Josephus as well as in the 1st century Jewish apocryphal work, the Assumption of Moses, where it is cast as a prophecy: An insolent king will succeed [the Hasmonean priests]… he will slay all the young.[12] [13] Other arguments against historicity include the silence of Josephus (who does record several other examples of Herod’s willingness to commit such acts to protect his power, noting that he "never stopped avenging and punishing every day those who had chosen to be of the party of his enemies")[14] and the views that the story is an apologetic device or a constructed fulfilment of prophesy.[15]

R. T. France argues for plausibility on the grounds that “the murder of a few infants in a small village [is] not on a scale to match the more spectacular assassinations recorded by Josephus”. [16] Paul L. Maier argues that sceptics have tended to "regard opinion as fact, and have largely avoided a careful historical search into the parameters of the problem". After analysing the arguments against the historicity of the infant massacre Maier concludes they all "have very serious flaws".[17] Maier follows Jerry Knoblet[18] in arguing for historicity based on the "identical personality profiles that emerge of Herod" in both Matthew and Josephus;[19]

Later accounts

The story's first appearance in any source other than Matthew is in the 2nd-century apocryphal Protoevangelium of James of c.150 AD, which excludes the Flight into Egypt and switches the attention of the story to the infant John the Baptist:

"And when Herod knew that he had been mocked by the Magi, in a rage he sent murderers, saying to them: Slay the children from two years old and under. And Mary, having heard that the children were being killed, was afraid, and took the infant and swaddled Him, and put Him into an ox-stall. And Elizabeth, having heard that they were searching for John, took him and went up into the hill-country, and kept looking where to conceal him. And there was no place of concealment. And Elizabeth, groaning with a loud voice, says: O mountain of God, receive mother and child. And immediately the mountain was cleft, and received her. And a light shone about them, for an angel of the Lord was with them, watching over them."[20]

The first non-Christian reference to the massacre is recorded four centuries later by Macrobius (c. 395-423), who writes in his Saturnalia:

"When he [emperor Augustus] heard that among the boys in Syria under two years old whom Herod, king of the Jews, had ordered to kill, his own son was also killed, he said: it is better to be Herod's pig, than his son."[21]

Macrobius' statement shows that the tradition of the massacre of the innocents had become firmly established in the culture at large, for the fact is that Christianity is not mentioned in any of his writings, despite the predominance it was asserting in every aspect of contemporary Roman life. As for his own sympathies, his vigorous interest in pagan rituals leaves scholars in no doubt that Macrobius was pagan. Indeed, his Saturnalia, with its idolization of Rome's pagan past, has been described as a pagan machine de guerre.[22]

The story assumed an important place in later Christian tradition; Byzantine liturgy estimated 14,000 Holy Innocents while an early Syrian list of saints stated the number at 64,000. Coptic sources raise the number to 144,000 and place the event on 29 December.[23] Taking the narrative literally and judging from the estimated population of Bethlehem, the Catholic Encyclopedia (1910) more soberly suggested that these numbers were inflated, and that probably only between six and twenty children were killed in the town, with a dozen or so more in the surrounding areas.[4]

In the arts

Medieval liturgical drama recounted Biblical events, including Herod's slaughter of the innocents. The Pageant of the Shearmen and Tailors, performed in Coventry, England, included a haunting song about the episode, now known as the Coventry Carol. The Ordo Rachelis tradition of four plays includes the Flight into Egypt, Herod's succession by Archelaus, the return from Egypt, as well as the Massacre all centred on Rachel weeping in fulfillment of Jeremiah's prophecy. These events were likewise in one of the Medieval N-Town Plays.

The theme of the "Massacre of the Innocents" has provided artists of many nationalities with opportunities to compose complicated depictions of massed bodies in violent action. It was an alternative to the Flight into Egypt in cycles of the Life of the Virgin. It decreased in popularity in Gothic art, but revived in the larger works of the Renaissance, when artists took inspiration for their "Massacres" from Roman reliefs of the battle of the Lapiths and Centaurs to the extent that they showed the figures heroically nude.[24] The horrific subject matter of the Massacre of the Innocents also provided a comparison of ancient brutalities with early modern ones during the period of religious wars that followed the Reformation - Bruegel's versions show the soldiers carrying banners with the Habsburg double-headed eagle (often used at the time for Ancient Roman soldiers).

The 1590 version by Cornelis van Haarlem also seems to reflect the violence of the Dutch Revolt. Guido Reni's early (1611) Massacre of the Innocents, in an unusual vertical format, is at Bologna.[25] The Flemish painter Peter Paul Rubens painted the theme more than once. One version, now in Munich, was engraved and reproduced as a painting as far away as colonial Peru.[26] Another, his grand Massacre of the Innocents is now at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto. The French painter Nicolas Poussin painted The Massacre of the Innocents (1634) at the height of the Thirty Years' War.

The Childermass, after a traditional name for the Feast of the Holy Innocents, is the opening novel of Wyndham Lewis's trilogy The Human Age. In the novel The Fall (La Chute) by Albert Camus, the incident is argued by the main character to be the reason why Jesus chose to let himself be crucified—as he escaped the punishment intended for him while many others died, he felt responsible and died in guilt. A similar interpretation is given in José Saramago's controversial The Gospel According to Jesus Christ, but there attributed to Joseph, Jesus' father, rather than to Jesus himself. As depicted by Saramago, Joseph knew of Herod's intention to massacre the children of Bethlehem, but failed to warn the townspeople and chose only to save his own child. Guilt-ridden ever after, Joseph finally expiates his sin by letting himself be crucified (an event not narrated in the New Testament).

The Massacre is the opening plot used in the 2006 movie The Nativity Story.

Feast days

The commemoration of the massacre of these "Holy Innocents"—considered by some Christians as the first martyrs for Christ[27]—first appears as a feast of the western church in the Leonine Sacramentary, dating from about 485. The earliest commemorations were connected with the Feast of the Epiphany, 6 January: Prudentius mentions the Innocents in his hymn on the Epiphany. Leo in his homilies on the Epiphany speaks of the Innocents. Fulgentius of Ruspe (6th century) gives a homily De Epiphania, deque Innocentum nece et muneribus magorum ("On Epiphany, and on the murder of the Innocents and the gifts of the Magi").[28]

Today, the date of Holy Innocents' Day, also called Childermas or Children's Mass, varies. 27 December is the date for West Syrians (Syriac Orthodox Church, Syro-Malankara Catholic Church, and Maronite Church) and East Syrians (Chaldeans and Syro-Malabar Catholic Church). 28 December is the date in the Church of England, the Lutheran Church and the Roman Catholic Church (in which, except on Sunday, violet vestments were worn before 1961, instead of red, the normal liturgical colour for celebrating martyrs). The Eastern Orthodox Church celebrates the feast on 29 December.

In the 1962 Roman Catholic calendar, the violet vestments for Holy Innocents were eliminated (red used instead), and if December 28 falls on Sunday, this feast is commemorated on the Sunday within the Octave of Christmas.

In Spain, Hispanic America and the Philippines[citation needed], December 28 is a day for pranks, equivalent to April Fool's Day in many countries. Pranks (bromas) are also known in Spain as inocentadas and their victims are called inocentes, or alternatively, the pranksters are the "inocentes" and the victims should not be angry at them, since they could not have committed any sin. One of the more famous of these traditions is the annual "Els Enfarinats" festival of Ibi in Alicante, where the inocentadas dress up in full military dress and incite a flour fight.[29] Various Catholic countries had a tradition (no longer widely observed) of role reversal between children and their adult educators, including boy bishops, perhaps a Christianized version of the Roman annual feast of the Saturnalia (when even slaves played "masters" for a day). In some cultures it is said to be an unlucky day, when no new project should be started.

In addition, there was a medieval custom of refraining where possible from work on the day of the week on which the feast of "Innocents Day" had fallen for the whole of the following year until the next Innocents Day. This was presumably mainly observed by the better-off. Philippe de Commynes, the minister of King Louis XI of France tells in his memoirs how the king observed this custom, and describes the trepidation he felt when he had to inform the king of an emergency on the day.[30]

Notes

- ^ Matthew 2:16-18

- ^ (Matthew 2:17 - "Then was fulfilled that being declared by Jeremiah the prophet so-saying.")

- ^ a b Compare Jeremiah 31:15. See also Jesus and Messianic prophecy#Jeremiah 31:15

- ^ a b Holy Innocents in The Catholic Encyclopedia: "The Greek Liturgy asserts that Herod killed 14,000 boys (ton hagion id chiliadon Nepion), the Syrians speak of 64,000, many medieval authors of 144,000, according to Apocalypse 14:3. Writers who accept the historicity of the episode reduce the number considerably, since Bethlehem was a rather small town. Joseph Knabenbauer brings it down to fifteen or twenty (Evang. S. Matt., I, 104), August Bisping to ten or twelve (Evang. S. Matt.), Lorenz Kellner to about six (Christus und seine Apostel, Freiburg, 1908); cf. "Anzeiger kath. Geistlichk. Deutschl.", 15 Febr., 1909, p. 32."

- ^ "most recent biographies of Herod the Great deny it entirely." Paul L. Maier, "Herod and the Infants of Bethlehem", in Chronos, Kairos, Christos II, Mercer University Press (1998), p.170

- ^ Compare Hosea 11:1. See also Jesus and Messianic prophecy#Hosea 11:1

- ^ Stephen L. Harris, Understanding the Bible, 2nd Ed. Palo Alto: Mayfield, 1985, p.274

- ^ Raymond E. Brown, The Birth of the Messiah, pp.104-121.

- ^ Raymond E. Brown, The Birth of the Messiah, pp.104-121.

- ^ "most recent biographies of Herod the Great deny it entirely." Paul L. Maier, "Herod and the Infants of Bethlehem", in Chronos, Kairos, Christos II, Mercer University Press (1998), p.172

- ^ Geza Vermes, The Nativity: History and Legend, London, Penguin, 2006, p22; E. P. Sanders, The Historical Figure of Jesus, Penguin, 1993, p.85

- ^ Assumption of Moses 6:2–6

- ^ Robert Eisenman, James The Brother of Jesus, 1997, I.3 "Romans, Herodians and Jewish sects," p.49; see also E. P. Sanders, The Historical Figure of Jesus, 1993, p.87-88

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, Book XV (at Wikisource).

- ^ Paul L. Maier, "Herod and the Infants of Bethlehem", in Chronos, Kairos, Christos II, Mercer University Press (1998), p.172-175

- ^ R T France “The Gospel of Matthew” 2007 NICNT

- ^ Paul L. Maier, "Herod and the Infants of Bethlehem", in Chronos, Kairos, Christos II, Mercer University Press (1998), p.185

- ^ Jerry Knoblet, "Herod the Great", Hamilton Books (2005), p.166

- ^ Paul L. Maier, "Herod and the Infants of Bethlehem", in Chronos, Kairos, Christos II, Mercer University Press (1998), p.186

- ^ Protoevangelium of James at newadvent.org.

- ^ "Cum audisset inter pueros quos in Syria Herodes rex Iudaeorum intra bimatum iussit interfici filium quoque eius occisum, ait: Melius est Herodis porcum esse quam filium," (Ambrosius Theodosius Macrobius, Saturnalia, book II, chapter IV:11).

- ^ Alan Cameron (1967). "Macrobius, Avienus, and Avianus". The Classical Quarterly 17 (2): 385–399.

- ^ E. Porcher, ed. and tr., Histoire d'Isaac, patriarche Jacobite d'Alexandrie de 686 à 689, écrite par Mina, évêque de Pchati, volume 11. 1915. Texts in Arabic, Greek and Syriac, p. 526.

- ^ Getty Collection

- ^ Reni's painting at the Web Gallery of Art

- ^ The Massacre of the Innocents in Cuzco Cathedral is clearly influenced by Rubens. See CODART Courant, Dec 2003, 12. (2.5 MB pdf download)

- ^ Sir William Smith and Samuel Cheetham , A dictionary of Christian antiquities, s.v. "Innocents, Festival of the" notes Irenaeus (Adv. Haer. iii.16.4) and Cyprian (Epistle 56) at the head of an extensive list.

- ^ Prudentius, Leo and Fulgentius are noted in Sir William Smith and Samuel Cheetham, A dictionary of Christian antiquities, s.v. "Innocents, Festival of the".

- ^ BBC News report of the 2010 festival.

- ^ Philippe de Commynes trans. Michael Jones, Memoirs, pp. 253-4, 1972, Penguin, ISBN 0140442642

See also

References

- Albright, W.F. and C.S. Mann. "Matthew." The Anchor Bible Series. New York: Doubleday & Company, 1971.

- Clarke, Howard W. The Gospel of Matthew and its Readers: A Historical Introduction to the First Gospel. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2003.

- Robert Eisenman, 1997. James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls (Viking/Penguin)

- Goulder, M.D. Midrash and Lection in Matthew. London: SPCK, 1974.

- Jones, Alexander. The Gospel According to St. Matthew. London: Geoffrey Chapman, 1965.

- Schweizer, Eduard. The Good News According to Matthew. Atlanta: John Knox Press, 1975.

External links

- Catholic Encyclopedia: "Holy Innocents"

- Images of the "Massacre of the Innocents"

- The Holy Martyred 14,000 Infants

Massacre of the Innocents

Life of Jesus: The NativityPreceded by

Flight into EgyptNew Testament

EventsDeath of Herod,

further succeeded by

Boy Jesus at JerusalemCategories:- Gospel of Matthew

- Christian festivals and holy days

- December observances

- New Testament words and phrases

- Christian iconography

- Murdered children

- Christian martyrs

- Child saints

- Anglican saints

- People celebrated in the Lutheran liturgical calendar

- Gospel episodes

- Saints days

- Herod the Great

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.