- Calvary

-

- For alternative meanings, see: Calvary (disambiguation), Mount Calvary (disambiguation), and Golgotha (disambiguation).

Traditional site of Golgotha, within the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

Traditional site of Golgotha, within the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

Calvary or Golgotha (English pronunciation: /ˈɡɒlɡəθə/) was the site, outside of ancient Jerusalem’s early first century walls, at which the crucifixion of Jesus is said to have occurred. Calvary and Golgotha are the English names for the site used in Western Christianity. Golgotha is the Greek transcription given by the New Testament, of an Aramaic title, which has traditionally been presumed to be Gûlgaltâ (but see below for an alternative); the Bible glosses it as place of [the] skull — Κρανίου Τόπος (Kraniou Topos) in Greek, and Calvariae Locus in Latin, from which we get Calvary.

Contents

Biblical references and etymology

The altar at the traditional site of Golgotha.

The altar at the traditional site of Golgotha.

Golgotha is referred to in early writings as being a hill looking like the skull-pan of a head very near a gate into the city of Jerusalem.

- Origen Against Marcion Book II (259 C.E.): A spot there is called Golgotha, - of old the fathers' earlier tongue thus called its name, "The skull-pan of a head".

Since the 6th century it has been referred to as the location of a mountain,[1] and as a small hill since 333.[2] The Gospels describe it as a place near enough to the city that those coming in and out could read the inscription 'Jesus of Nazareth - King of the Jews'[3] . When the King James Version was written, the translators used an anglicised version — Calvary — of the Latin gloss from the Vulgate (Calvariæ), to refer to Golgotha in the Gospel of Luke, rather than translate it; subsequent uses of Calvary stem from this single translation decision. The location itself is mentioned in all four canonical Gospels:

- Luke: And when they came to the place which is called The Skull, there they crucified him, and the criminals, one on the right and one on the left.[6]

- John: So they took Jesus, and he went out, bearing his own cross, to the place called the place of a skull, which is called in Hebrew Gol'gotha.[7]

The “place of a skull” etymology is based on the Hebrew verbal root גלל g-l-l, from which the Hebrew word for skull, גֻלְגֹּלֶת (gulggolet),[8] is derived. A number of alternative explanations have been given for the name. It has been suggested that the Aramaic name is actually Gol Goatha, meaning mount of execution, possibly the same location as the Goatha mentioned in a Book of Jeremiah passage,[9] describing the geography of Jerusalem[2] An alternative explanation is that the location was a place of public execution, and the name refers to abandoned skulls that would be found there,[10] or that the location was near a cemetery, and the name refers to the bones buried there.[2]

In some Christian and Jewish traditions, the name Golgotha refers to the location of the skull of Adam.[1] A common version states that Shem and Melchizedek traveled to the resting place of Noah's Ark, retrieved the body of Adam from it, and were led by Angels to Golgotha — described as a skull-shaped hill at the centre of the Earth, where also the serpent's head had been crushed following the Fall of man. This tradition appears in numerous older sources, including the Kitab al-Magall, the Conflict of Adam and Eve with Satan, the Cave of Treasures, and the writings of Patriarch Eutychius of Alexandria. It is also suggested that the location's landscape resembled the shape of a skull, and gained its name for that reason.[2]

Traditional location

The traditional location of Golgotha derives from its identification by Helena, the mother of Constantine I, in 325. A few yards nearby, Helena also identified the location of the Tomb of Jesus and claimed to have discovered the True Cross; her son, Constantine, then built the Church of the Holy Sepulchre around the whole site. In 333, the Pilgrim of Bordeaux, entering from the east described the result:

“ On the left hand is the little hill of Golgotha where the Lord was crucified. About a stone's throw from thence is a vault [crypta] wherein his body was laid, and rose again on the third day. There, at present, by the command of the Emperor Constantine, has been built a basilica; that is to say, a church of wondrous beauty.[11] ” In Nazénie Garibian de Vartavan's doctoral thesis, now published as La Jérusalem Nouvelle et les premiers sanctuaires chrétiens de l’Arménie. Méthode pour l’étude de l’église comme temple de Dieu, she concluded, through multiple arguments (mainly theological and archaeological), that the true site of Golgotha was precisely at the vertical of the now buried Constantinian basilica's altar and away from where the traditional rock of Golgotha is situated.[12] The plans published in the book indicate the location of the Golgotha within a precision of less than two meters, below the circular passage situated a metre away from where the blood stained shirt of Christ was traditionally recovered and immediately before the stairs leading down to "St. Helena's Chapel" (the above mentioned mother of Emperor Constantine), alternatively called "St. Vartan's Chapel".

The temple to Aphrodite

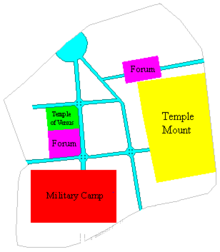

Jerusalem after being rebuilt by Hadrian. Two main east-west roads were built rather than the typical one, due to the awkward location of the Temple Mount, blocking the central east-west route.

Prior to Helena's identification, the site had been a temple to Aphrodite. Constantine's construction took over most of the site of the earlier temple enclosure, and the Rotunda and cloister (which was replaced after the 12th century by the present Catholicon and Calvary chapel) roughly overlap with the temple building itself; the basilica church which Constantine built over the remainder of the enclosure was destroyed at the turn of the 11th century, and has not been replaced. Christian tradition justifies this re-use by claiming that the location had originally been a Christian place of veneration, but that Hadrian had deliberately buried these Christian sites and built his own temple on top, on account of his alleged hatred for Christianity.[13] There is certainly evidence that just 30 years after Hadrian's temple had been built, Christians associated it with the site of Golgotha; Melito of Sardis, a late 2nd century bishop in the region, described the location as in the middle of the street, in the middle of the city,[14] which matches the position of Hadrian's temple within the late 2nd century city.

However, Hadrian's temple had actually been located there simply because it was the junction of the main north-south road[citation needed] (which is now the Suq Khan-ez-Zeit, etc.) with one of the two main east-west roads (which is now the Via Dolorosa), and directly adjacent to the forum (which is now the location of the (smaller) Muristan); the forum itself had been placed, as is traditional in Roman towns, at the junction of the main north-south road with the (other) main east-west road (which is now El-Bazar/David Street). The temple and forum together took up the entire space between the two main east-west roads (a few above-ground remains of the east end of the temple precinct still survive in the Russian Mission in Exile).[citation needed]

Questions of the location in relation to the city walls

The New Testament describes the crucifixion site, Golgotha, as being "near the city" (John 19:20), and "outside the city wall" (Heb. 13:12). The traditionally identified location is in the heart of Hadrian's city, well within Jerusalem's Old City Walls; there has therefore been some questioning of the legitimacy of the traditional identification on these grounds. Some defenders of this tradition have responded by citing Jewish history of the wall, that the city had been much narrower in Jesus' time, with the site then having been outside the walls; since Herod Agrippa (41–44) is recorded by history as extending the city to the north (beyond the present northern walls), the required repositioning of the western wall is traditionally attributed to him as well. In 2003, Professor Sir Henry Chadwick (former Dean of Christ Church, Oxford) argued that when Hadrian's builders replanned the old city, they "incidentally confirm[ed] the bringing of Golgotha inside a new town wall."[15]

Some Protestant advocates of an alternative site claim that a wall would imply the existence of a defensive ditch outside it, so an earlier wall couldn't be immediately adjacent to the Golgotha site, which combined the presence of the Temple Mount would make the city inside the wall quite thin; essentially for the traditional site to have been outside the wall, the city would have had to be limited to the lower parts of the Tyropoeon Valley, rather than including the defensively advantageous western hill. Since these geographic considerations imply that not including the hill within the walls would be willfully making the city prone to attack from it, some scholars, including the late 19th century surveyors of the Palestine Exploration Fund, consider it unlikely that a wall would ever have been built which would cut the hill off from the city in the valley;[16] archaeological evidence for the existence an earlier city wall in such a location has never been found.

In another viewpoint, in 2007 Dan Bahat, the former City Archaeologist of Jerusalem and Professor of Land of Israel Studies at Bar-Ilan University, stated that "Six graves from the first century were found on the area of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. That means, this place [was] outside of the city, without any doubt…".[17] The dating of the tombs is based on the fact that they are in the kokh style, which was common in 1st century; however, the kokh style of tomb was also common in the 2nd and 3rd centuries BC.[18]

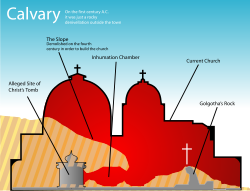

The rockface

During 1973–1978 restoration works, and excavations, inside the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, and under the nearby Muristan, it was found that the area was originally a quarry, from which white Meleke limestone was struck;[19] surviving parts of the quarry, to the north-east of the chapel of St. Helena, are now accessible from within the chapel (by permission). Inside the church is a rock, about 7 m long by 3 m wide by 4.8 m high,[19] that is traditionally believed to be all that now remains visible of Golgotha; the design of the church means that the Calvary Chapel contains the upper foot or so of the rock, while the remainder is in the chapel beneath it (known as the tomb of Adam). Virgilio Corbo, a Franciscan priest and archaeologist, present at the excavations, suggested that from the city the little hill (which still exists) could have looked like a skull.[20]

During a 1986 repair to the floor of the Calvary Chapel, by the art historian George Lavas and architect Theo Mitropoulos, a round slot of 11.5 cm diameter was discovered in the rock, partly open on one side (Lavas attributes the open side to accidental damage during his repairs);[21] although the dating of the slot is uncertain, and could date to Hadrian's temple of Aphrodite, Lavas suggested that it could have been the site of the crucifixion, as it would be strong enough to hold in place a wooden trunk of up to 2.5 m height (among other things).[22][23] The same restoration work also revealed a crack running across the surface of the rock, which continues down to the Chapel of Adam;[21] the crack is thought by archaeologists to have been a result of the quarry workmen encountering a flaw in the rock.[24]

Profile based on attempted reconstruction by a German documentary[who?].

Profile based on attempted reconstruction by a German documentary[who?].

Based on the late 20th century excavations of the site, there have been a number of attempted reconstructions of the profile of the cliff face; these often attempt to show the site as it would have appeared to Constantine. However, as the ground level in Roman times was about 4–5 feet lower, and the site housed Hadrian's temple to Aphrodite, much of the surrounding rocky slope must have been removed long before Constantine built the church on the site. The height of the Golgotha rock itself would have caused it to jut through the platform level of the Aphrodite temple, where it would be clearly visible; the reason for Hadrian not cutting the rock down is uncertain, but Virgilio Corbo suggested that a statue, probably of Aphrodite, was placed on it,[25] a suggestion also made by Jerome. Some archaeologists have been suggested that prior to Hadrian's use, the rock outcrop had been a nefesh - a Jewish funeral monument, equivalent to the stele.[26]

Pilgrimages to Constantine's Church

Icon of Jesus being led to Golgotha, 16th century, Theophanes the Cretan (Stavronikita Monastery, Mount Athos).

Icon of Jesus being led to Golgotha, 16th century, Theophanes the Cretan (Stavronikita Monastery, Mount Athos).

The Itinerarium Burdigalense speaks of Golgotha in 333: "... On the left hand is the little hill of Golgotha where the Lord was crucified. About a stone's throw from thence is a vault (crypta) wherein His body was laid, and rose again on the third day. There, at present, by the command of the Emperor Constantine, has been built a basilica, that is to say, a church of wondrous beauty,"[27] Cyril of Jerusalem, a distinguished theologian of the early Church, and eyewitness to the early days of Constantine's edifice, speaks of Golgotha in eight separate passages, sometimes as near to the church in which he and his listeners were assembled:[28] "Golgotha, the holy hill standing above us here, bears witness to our sight: the Holy Sepulchre bears witness, and the stone which lies there to this day."[29] And just in such a way the pilgrim Egeria often reported in 383: "… the church, built by Constantine, which is situated in Golgotha …",[30] and also bishop Eucherius of Lyon wrote to the island presbyter Faustus in 440: "Golgotha is in the middle between the Anastasis and the Martyrium, the place of the Lord's passion, in which still appears that rock which once endured the very cross on which the Lord was.",[31] and Breviarius de Hierosolyma reports in 530: "From there (the middle of the basilica), you enter into Golgotha, where there is a large court. Here the Lord was crucified. All around that hill, there are silver screens."[32] (See also: Eusebius in 338[33]).

Alternative locations

Rocky escarpment that some claim to resemble the face of a skull, located northwest of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, near the Garden Tomb which had never been recognized by any church. In the foreground is an 1880 photograph of the same rock face.

In 1882–83, Major-General Charles George Gordon proposed a different location. The location, which some Protestants call the Garden Tomb, is beneath a cliff which contains two large sunken holes, which Gordon regarded as resembling the eyes of a skull; he and a few others before him believed that the skull-like appearance would have caused the location to be known as Golgotha.

The Garden Tomb contains several ancient burial places, although pottery and archaeological findings in the area have been dated to the 7th century BC, so the site would have been abandoned by the 1st century.[34] Eusebius comments that Golgotha was in his day (the 4th century) pointed out north of Mount Zion.[35] Although the hill currently referred to as Mount Zion is indeed south of the traditional site for Golgotha, it has only had that name since the Middle Ages, and previously 'Mount Zion' referred to the Temple Mount itself. The Garden Tomb is north of both.

Another alternate location has been proposed by Rodger Dusatko, a missionary in Germany. He claims that the location is just outside the Lion's gate.[36]

He has written a book about the correlation between the crucifixion of Jesus and the sacrifice of the Red Heifer (400 pages - http://www.dusatko.de/redheifer.pdf). In this book he describes in detail the view of the priest who sacrificed the Red Heifer. It is mentioned in Num 19,4 that he must look towards the entrance of the temple as he sprinkles the blood. In his book, Rodger Dusatko claims that this view went directly over the place on Golgotha where Jesus was crucified. He has also written a small summary on the location of Golgotha.[37]

All of his works, both the books as well as the pictures, may be distributed freely as stated at http://www.dusatko.de/books.aspx

Other uses of the name

Golgotha (Crucifixion icon), Orthodox Cathedral in Vilnius.

- The name Calvary often refers to sculptures or pictures representing the scene of the crucifixion of Jesus, or a small wayside shrine incorporating such a picture. It also can be used to describe larger, more monumentlike constructions, essentially artificial hills often built by devotees, especially a tradition in Brittany in France of large stone monuments.

- Churches in various Christian denominations have been named Calvary. The name is also sometimes given to cemeteries, especially those associated with the Roman Catholic Church.

- Two Catholic religious orders have been dedicated to Mount Calvary. Several places worldwide have been named after it; including the town Kalvarija in Lithuania and towns Góra Kalwaria and Kalwaria Zebrzydowska in Poland.

- In the 18th and early 19th centuries at Oxford and Cambridge universities the rooms of the heads of colleges and halls were nicknamed golgotha. Apart from the obvious pun on the place of skulls (i.e. heads), this was also due to the punishments that students received in these rooms.[38]

- In the Eastern Orthodox Church, a Golgotha is a representation (icon) of the crucified Jesus, often with the Theotokos (Mother of God) and John the Beloved Disciple standing to either side. This is used during Holy Week, especially during the Matins of Great Friday (Good Friday). During the rest of the year, it may stand in the nave of the church, off to one side, and will be the place where Pannikhidas (memorial services) will be chanted.

See also

Notes

- ^ a b "Mount Calvary". Vol. III. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1908. http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03191a.htm.

- ^ a b c d Catholic Encyclopedia, Golgotha

- ^ John 19:20

- ^ Mark 15:22

- ^ Matthew 27:33

- ^ Luke 23:33

- ^ John 19:17

- ^ Lande, George M. (2001) [1961]. Building Your Biblical Hebrew Vocabulary Learning Words by Frequency and Cognate. Resources for Biblical Study 41. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. p. 115. ISBN 1589830032. http://www.sbl-site.org/publications/ICI_Resources_Biblical_study.aspx.

- ^ Jeremiah 31:39

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia, Golgotha

- ^ Itinerarium Burdigalense, pages 593, 594

- ^ Garibian de Vartavan, N. (2008). La Jérusalem Nouvelle et les premiers sanctuaires chrétiens de l’Arménie. Méthode pour l’étude de l’église comme temple de Dieu. London: Isis Pharia. ISBN 0-9527827-7-4.

- ^ Eusebius, Life of Constantine, 3:26

- ^ Melito of Sardis, On Easter

- ^ Chadwick, H. (2003). The Church in Ancient Society: From Galilee to Gregory the Great. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 21. ISBN 0-199-26577-1.

- ^ Colonel Claude R. Conder, The City of Jerusalem (1909), (republished 2004); for details about Conder himself, see Herbert Kitchener, 1st Earl Kitchener#Survey of Western Palestine

- ^ Dan Bahat in German television ZDF, April 11, 2007

- ^ Rachel Hachlili, (2005) Jewish Funerary Customs, Practices and Rites in the Second Temple Period

- ^ a b Hesemann, Michael (1999). Die Jesus-Tafel. Freiburg. p. 170. ISBN 3-451-27092-7. (German)

- ^ Hesemann 1999, p.170: "Von der Stadt aus muß er tatsächlich wie eine Schädelkuppe ausgesehen haben," and page 190: a sketch; and page 172: a sketch of the geological findings by C. Katsimbinis, 1976: "der Felsblock ist zu 1/8 unterhalb des Kirchenbodens, verbreitert sich dort auf etwa 6,40 Meter und verläuft weiter in die Tiefe"; and page 192, a sketch by Corbo, 1980: Golgotha is distant 10 meters outside from the southwest corner of the Martyrion-basilica

- ^ a b George Lavas, The Rock of Calvary, published (1996) in The Real and Ideal Jerusalem in Jewish, Christian and Islamic Art (proceedings of the 5th International Seminar in Jewish Art), pages 147-150

- ^ Hesemann 1999, pp. 171-172:"....Georg Lavas and ... Theo Mitropoulos, ... cleaned off a thick layer of rubble and building material from one to 45 cm thick which covered the actual limestone. The experts still argue whether this was the work of the architects of Hadrian, who aimed thereby to adapt the rock better to the temple plan, or whether it comes from 7th century cleaning....When the restorers progressed to the lime layer and the actual rock....they found they had removed a circular slot of 11.5 cm diameter".

- ^ Vatican-magazin.com, Vatican 3/2007, page 12; here page 3 photo No. 4, quite right, photo by Paul Badde: der steinere Ring auf dem Golgothafelsen.

- ^ Holyplacesinisrael.com

- ^ Virgilio Corbo, The Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem (1981)

- ^ Dan Bahat, Does the Holy Sepulchre Church Mark the Burial of Jesus?, in Biblical Archaeology Review May/June 1986

- ^ THE ANONYMOUS PILGRIM OF BORDEAUX pages 593 and 594

- ^ St. Cyril of Jerusalem, page 51, note 313

- ^ Cyril, Catechetical Lectures, year 347, lecture X, page 160, note 1221

- ^ Iteneraria Egeriae

- ^ Letter To The Presbyter Faustus, by Eucherius. "What is reported, about the site of the city Jerusalem and also of Judaea"; Epistola Ad Faustum Presbyterum. "Eucherii, Quae fertur, de situ Hierusolimitanae urbis atque ipsius Iudaeae." Corpus Scriptorum Eccles. Latinorum XXXIX Itinera Hierosolymitana, Saeculi IIII–VIII, P. Geyer, 1898

- ^ Whalen, Brett Edward, Pilgrimage in the Middle Ages, page 40, University of Toronto Press, September 2011, ISBN 978-1442601994; Iteneraria et alia geographica, Corpus Christianorum Series Latina, vol. 175 (Turnhout,Brepols 1965), pages 109-112

- ^ Vita Constantini III, 35, Description of the Atrium and Porticos

- ^ Gabriel Barkay, The Garden Tomb, published in Biblical Archaeology Review March/April 1986

- ^ Eusebius, Onomasticon, 365

- ^ http://www.golgotha.eu

- ^ http://www.dusatko.de/golgotharediscovered.pdf

- ^ Amhurst, Nicholas (1726). Terræ filius: or the secret history of the university of Oxford

. R. Francklin. p. 59 [scan]

. R. Francklin. p. 59 [scan]  .

.

Coordinates: 31°46′43″N 35°13′46″E / 31.77861°N 35.22944°E

Categories:- Alleged tombs of Jesus

- Hills

- New Testament places

- New Testament Latin words and phrases

- Christian terms

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.