- Road to Emmaus appearance

-

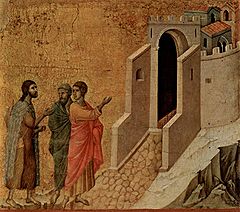

The Road to Emmaus appearance refers to one of the early resurrection appearances of Jesus after his crucifixion and the discovery of the empty tomb.[1][2] Both the Meeting on the road to Emmaus and the subsequent Supper at Emmaus, depicting the meal Jesus had with the two disciples after the encounter on the road, have been popular subjects in art .

Contents

Biblical accounts

The Gospel of Luke 24:13-32 describes the encounter on the road and the supper, and states that while a disciple named Cleopas was walking towards Emmaus with another disciple, they met Jesus. They did not recognise him, and discussed their sadness at recent events with him. They persuaded him to come and eat with them, and in the course of the meal they recognised him.

The Gospel of Mark 16:12-13 has a similar account that describes the appearance of Jesus to two disciples while they were walking in the country, at about the same time in the Gospel narrative.[3] although it does not name the disciples or the destination as Emmaus:

Afterward Jesus appeared in a different form to two of them while they were walking in the country. These returned and reported it to the rest; but they did not believe them either.[4]

The Gospel of Luke states that Jesus stayed and had supper with the two disciples, after the encounter on the road:

As they approached the village to which they were going, Jesus acted as if he were going farther. But they urged him strongly, "Stay with us, for it is nearly evening; the day is almost over." So he went in to stay with them. [5]

The detailed narration of this episode is at times considered one of the best sketches of a biblical scene in the Gospel of Luke.[6] In this account, when Jesus appeared to Cleopas and one other disciple at first "their eyes were holden" so that they could not recognize him. Later "in the breaking of bread" "their eyes were opened" and they recognized him. B. P. Robinson argues that this means the recognition occurred in the course of the meal,[7] but Raymond Blacketer notes that "Many, perhaps even most, commentators, ancient and modern and in-between, have seen the revelation of Jesus' identity in the breaking of bread as having some kind of eucharistic referent or implication."[8]

Many of the Gnostics believed that Jesus, being not really human, was able to change his appearance at will, and these accounts, along with others in Gnostic New Testament apocrypha were cited in support of this belief.[9]

In art

Both the encounter on the road, and the ensuing supper have been depicted in art, but the supper has received more attention. Medieval art tends to show a moment before Jesus is recognised; Christ wears a large floppy hat to help explain the initial lack of recognition by the disciples. This is often a large pilgrim's hat with badges or, rarely, a Jewish hat. However, the depiction of the next part of the episode, the supper at Emmaus, which shows Jesus eating with the disciples, has been a more popular theme, at least since the Renaissance. Often the moment of recognition is shown.

Rembrandt's 1648 depiction of the Supper, at the Louvre builds on the earlier etching he did six years earlier, in which the disciple on the left had risen, hands clasped in prayer. In both depictions the disciples are startled, and are in awe, but not in fear. The servant is oblivious to the theophanic moment taking place during the supper.[10]

Both Caravaggio's painting in London and his painting in Milan (which were six years apart) imitate natural color very well, but were criticised for lack of decorum. Caravaggio depicted Jesus without a beard and the London painting shows fruits on the table that are out of season. Moreover, the inn keeper is shown serving with a hat.[11]

Some other artists who have portrayed the Supper are Jacopo Bassano, Pontormo, Vittore Carpaccio, Philippe de Champaigne, Albrecht Dürer, Benedetto Gennari, Jacob Jordaens, Marco Marziale, Pedro Orrente, Tintoretto, Titian, Velázquez and Paolo Veronese. The supper was also the subject of one of his most successful Vermeer forgeries by Han van Meegeren.

In literary art, the Emmaus theme is realized as early as in the 12th century by the Durham poet Laurentius in a semidramatic Latin poem.[12]

Gallery of art

-

Oratory in Novara, 15th century

-

Supper at Emmaus, 15th century

-

The Meeting, by Lelio Orsi, 1560-65

-

after Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1571

-

Caravaggio, 1601, London

-

Caravaggio, 1606, Milan

-

Diego Velázquez, 1620, New York

-

Laurent de La Hyre, 1656

-

Joseph von Führich, 1837

Jungian Perspective

Carl Jung regarded the road to Emmaus appearance as an instance of the mythological theme of the magical traveling companion that still appears spontaneously in dreams today.[13] Commenting on a dream of Wolfgang Pauli Jung stated that the road to Emmaus appearance was similar to Krishna and Arjuna in the Bhagavad Gita, and to Moses and El-Khidr in Sura 18 of the Koran.

See also

- Chronology of Jesus

- Gospel harmony

- Resurrection appearance of Jesus

- Resurrection of Jesus

Notes

- ^ Luke by Fred B. Craddock 1991 ISBN 0-8042-3123-0 page 284

- ^ Exploring the Gospel of Luke: an expository commentary by John Phillips 2005 ISBN 0-8254-3377-0 pages 297-230

- ^ Catholic Comparative New Testament by Oxford University Press 2006 ISBN 0-19-528299-X page 589

- ^ Bible gateway

- ^ Bible gateway

- ^ Luke for Everyone by Tom Wright, 2004 ISBN 0-664-22784-8 page 292

- ^ B. P. Robinson, "The Place of the Emmaus Story in Luke-Acts," NTS 30 [1984], 484.

- ^ Raymond A. Blacketer, "Word and Sacrament on the Road to Emmaus: Homiletical Reflections on Luke 24:13-35," CTJ 38 [2003], 323.

- ^ Hoeller, pp. 64-65

- ^ The Biblical Rembrandt by John I. Durham 2004 ISBN 0-86554-886-2 page 144

- ^ Art, creativity, and the sacred: an anthology in religion and art by Diane Apostolos-Cappadona 1995 ISBN 0-8264-0829-X page 64

- ^ Udo Kindermann, ‘Das Emmausgedicht des Laurentius von Durham’, in: Mittellateinisches Jahrbuch 5 (1968), S. 79-100.

- ^ Jung, C.G. (1968), Psychology and Alchemy, Collected Works, Volume 12, Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01831-6 page ??

References

- James Hall, A History of Ideas and Images in Italian Art, 1983, John Murray, London, ISBN 0-7195-3971-4

- Hoeller, Stephan A., Gnosticism: new light on the ancient tradition of inner knowing, Quest Books, 2002, ISBN 0-8356-0816-6, 9780835608169

Categories:- Gospel episodes

- New Testament narrative

- Christian iconography

- Gospel of Luke

-

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.