- Jersey City, New Jersey

-

City of Jersey City — City — Skyline of Downtown Jersey City

SealNickname(s): "Chilltown"[1]

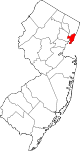

"Wall Street West"[2]Motto: “Let Jersey Prosper” Location of Jersey City within Hudson County. Inset: Location of Hudson County highlighted within the state of New Jersey. Census Bureau map of Jersey City, New Jersey Coordinates: 40°42′41″N 74°03′53″W / 40.71139°N 74.06472°WCoordinates: 40°42′41″N 74°03′53″W / 40.71139°N 74.06472°W Country United States State New Jersey County Hudson Government – Type Faulkner Act (Mayor-Council) – Mayor Jerramiah Healy (2013)[3] – Business Administrator John "Jack" Kelly[4] Area[5] – Total 21.11 sq mi (54.7 km2) – Land 14.92 sq mi (38.6 km2) – Water 6.20 sq mi (16.1 km2) 29.37% Elevation[6] 20 ft (6 m) Population (2010 Census)[7] – Total 247,597 – Density 16,613.2/sq mi (6,414.4/km2) Time zone EST (UTC-5) – Summer (DST) EDT (UTC-4) ZIP codes 07097, 07302-07308, 07310-07311[8] Area code(s) 201 and 551 FIPS code 34-36000[9][10] GNIS feature ID 0885264[11] Website http://www.cityofjerseycity.com Jersey City is the seat of Hudson County, New Jersey, United States.

Part of the New York metropolitan area, Jersey City lies between the Hudson River and Upper New York Bay across from Lower Manhattan and the Hackensack River and Newark Bay. A port of entry, with 11 miles (18 km) of waterfront and significant rail connections, Jersey City is an important transportation terminus and distribution and manufacturing center for the Port of New York and New Jersey. Service industries have played a prominent role in the redevelopment of its waterfront and the creation of one of the nation's largest downtowns. As of the 2010 United States Census, the population of Jersey City was 247,597, making it the second-largest city in New Jersey.

Contents

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 21.11 square miles (54.7 km2), of which, 14.92 square miles (38.6 km2) of it is land and 6.20 square miles (16.1 km2), or 29.37%, of it is water.[5] It has the smallest land area of the 100 largest cities in America.[citation needed]

Jersey City is bordered to the east by the Hudson River, to the north by Secaucus, North Bergen, Union City and Hoboken, to the west, across the Hackensack, by Kearny and Newark, and to the south by Bayonne. Given its proximity to Manhattan, Jersey City and Hudson County are sometimes referred to as New York City's sixth borough.[12][13][14]

Image of Jersey City taken by NASA. (The red line demarcates the municipal boundaries of Jersey City.)

Image of Jersey City taken by NASA. (The red line demarcates the municipal boundaries of Jersey City.)

History

Lenape and New Netherland

The land comprising what is now Jersey City was inhabited by the Lenape, a collection of tribes (later called Delaware Indian). In 1609, Henry Hudson, seeking an alternate route to East Asia, anchored his small vessel Halve Maen (English: Half Moon) at Sandy Hook, Harsimus Cove and Weehawken Cove, and elsewhere along what was later named the North River. After spending nine days surveying the area and meeting its inhabitants, he sailed as far north as Albany. By 1621 the Dutch West India Company was organized to manage this new territory and in June 1623, New Netherland became a Dutch province, with headquarters in New Amsterdam. Michael Reyniersz Pauw received a land grant as patroon on the condition that he would establish a settlement of not fewer than fifty persons within four years. He chose the west bank of the North River (Hudson River) and purchased the land from the Lenape. This grant is dated November 22, 1630 and is the earliest known conveyance for what are now Hoboken and Jersey City. Pauw, however was an absentee landlord who neglected to populate the area and was obliged to sell his holdings back to the Company in 1633.[15] That year, a house was built at Communipaw for Jan Evertsen Bout, superintendent of the colony, which had been named Pavonia (the Latinized form of Pauw's name, which means peacock).[16] Shortly after, another house was built at Harsimus Cove and became the home of Cornelius Van Vorst, who had succeeded Bout as superintendent, and whose family would become influential in the development of the city. Relations with the Lenape deteriorated, in part because of the colonialist's mismanagement and misunderstanding of the indigenous people, and led to series of raids and reprisals and the virtual destruction of the settlement on the west bank. During Kieft's War, approximately eighty Lenapes were killed by the Dutch in a massacre at Pavonia on the night of February 25, 1643.[17]

Scattered communities of farmsteads characterized the Dutch settlements at Pavonia: Communipaw, Harsimus, Paulus Hook, Hoebuck, Awiehaken, and other lands "behind Kil van Kull". The first village (located inside a palisaded garrison) established on what is now Bergen Square in 1660, and is considered to be the oldest town in what would become the state of New Jersey.[18]

Early America

Among the oldest surviving houses in Jersey City is the stone Van Wagenen House of 1742. During the American Revolutionary War the area was in the hands of the British who controlled New York. Paulus Hook was attacked by Major Light Horse Harry Lee on August 19, 1779. After the war Alexander Hamilton and other prominent New Yorkers and New Jerseyeans attempted to develop the area that would become historic downtown Jersey City and laid out the city squares and streets that still characterize the neighborhood, giving them names also seen in Lower Manhattan or after war heroes (Grove, Varick, Mercer, Wayne, Monmouth, and Montgomery among them). During the 19th century, 60,000 former slaves reached Jersey City on one of the four routes of the Underground Railroad that led to the city.[19]

The City of Jersey was incorporated by an Act of the New Jersey Legislature on January 28, 1820, from portions of Bergen Township, while the area was still a part of Bergen County. The city was reincorporated on January 23, 1829, and again on February 22, 1838, at which time it became completely independent of North Bergen and was given its present name. On February 22, 1840, it became part of the newly-created Hudson County.[20]

Soon after the Civil War, the idea of uniting all of the towns of Hudson County east of the Hackensack River into one municipality. A bill was approved by the State legislature on April 2, 1869, a special held October 5, 1869. An element of the bill provide that only contiguous towns could be consolidated. While a majority of the voters approved the merger, only Jersey City, Hudson City and Bergen City could be consolidated, which they did on March 17, 1870. Three years later the present outline of Jersey City was completed when Greenville agreed to merge into the Greater Jersey City.[20][20][21]

20th century

Jersey City was a dock and manufacturing town for much of the 19th and 20th centuries. Much like New York City, Jersey City has always been a destination for new immigrants to the United States. In its heyday before World War II, German, Irish, and Italian immigrants found work at Colgate, Chloro, or Dixon Ticonderoga. However, the largest employers at the time were the railroads, whose national networks terminated on the Hudson River at Pavonia Terminal, Exchange Place and Communipaw. The Hudson Tubes opened in 1911, allowing passengers to take the train to Manhattan as an alternative to the extensive ferry system. The Black Tom explosion occurred on July 30, 1916 as an act of sabotage on American ammunition supplies by German agents to prevent the materials from being used by the Allies in World War I.[22]

From 1917 to 1947, Jersey City was governed by Mayor Frank Hague. Originally elected as a reform candidate, the Jersey City History Web Site says his name is "synonymous with the early twentieth century urban American blend of political favoritism and social welfare known as bossism." Hague ran the city with an iron fist while, at the same time, molding governors, United States senators, and judges to his whims. Boss Hague was known to be loud and vulgar, but dressed in a stylish manner earning him the nickname "King Hanky-Panky".[23] In his later years in office, Hague would often dismiss his enemies as "reds" or "commies". Hague lived like a millionaire, despite having an annual salary that never exceeded $8,500.[24] He was able to maintain a fourteen-room duplex apartment in Jersey City, a suite at the Plaza Hotel in Manhattan, and a palatial summer home in Deal, and travel to Europe yearly in the royal suites of the best liners.[24]

After Hague's retirement from politics, a series of mayors including John V. Kenny, Thomas J. Whelan, and Thomas F.X. Smith attempted to take control of Hague's organization, usually under the mantle of political reform. None was able to duplicate the level of power held by Hague,[25] but the city and the county remained notorious for political corruption for years.[26][27][28] By the 1970s, the city experienced a period of urban decline that saw many of its wealthy residents leave for the suburbs, rising crime, civil unrest, political corruption, and economic hardship. From 1950 to 1980, Jersey City lost 75,000 residents, and from 1975 to 1982, it lost 5,000 jobs, or 9% of its workforce.[29]

Beginning in the 1980s, development of the waterfront in an area previously occupied by rail yards and factories helped to stir the beginnings of a renaissance for Jersey City. The rapid construction of numerous high-rise buildings increased the population and led to the development of the Exchange Place financial district, also known as 'Wall Street West', one of the largest banking centers in the United States. Large financial institutions such as UBS, Goldman Sachs, Chase Bank, Citibank and Merrill Lynch occupy prominent buildings on the Jersey City waterfront, some of which are among the tallest buildings in New Jersey. Simultaneous to this building boom, the light-rail network was developed.[30] With 18,000,000 square feet (1,700,000 m2) of office space, it has the nation's 12th largest downtown.[31]

Demographics

Historical populations Census Pop. %± 1840 3,072 — 1850 6,856 123.2% 1860 29,226 326.3% 1870 82,546 182.4% 1880 120,722 46.2% 1890 163,003 35.0% 1900 206,433 26.6% 1910 267,779 29.7% 1920 298,103 11.3% 1930 316,715 6.2% 1940 301,173 −4.9% 1950 299,017 −0.7% 1960 276,101 −7.7% 1970 260,350 −5.7% 1980 223,532 −14.1% 1990 228,537 2.2% 2000 240,055 5.0% 2010 247,597 3.1% historical data sources:

[32] 1920[33] 1930-1990[34] 2000[35] 2010[7]As of the 2010 United States Census, the population of Jersey City was 247,597, maintaining its position as the second-largest city in New Jersey, after Newark, reflecting an increase of 7,542 residents (3.1%) from its 2000 Census population of 240,055.[36] [37] Since it is believed the earlier population was under documented, the 2010 census was anticipated with the possibility that Jersey City might become the state's most populated city, surpassing Newark.[7] The city has hired an outside firm to contest the results, citing the fact that development between 2000 and 2010 substantially increased the number of housing units and that new populations may have been undercounted.[38][39] Preliminary fidings indicated that 19,000 housing units went uncounted.[40]

As of the 2000 United States Census the population was 240,055 making Jersey City the 72nd most populous city in the U.S.[41] Among cities with a population higher than 100,000 ranked in the 2000 Census, Jersey City was the fourth most densely populated large city in the United States, behind New York City, Paterson, New Jersey and San Francisco.[42] There were 88,632 households, and 55,660 families residing in the city. The population density was 6414.4/km2 (16,617.2/mi2). There were 93,648 housing units at an average density of 6,278.3 per square mile (2,423.4/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 34.01% White, 28.32% African American, 0.45% Native American, 16.20% Asian, 0.08% Pacific Islander, 15.11% from other races, and 5.84% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 28.31% of the population.[35]

Largest ancestries include: Italian (6.6%), Irish (5.6%), Polish (3.0%), Arab (2.8%), and German (2.7%).[43]

Of all households, 31.1% had children under the age of 18 living there, 36.4% were married couples living together, 20.2% had a female householder with no husband present, and 37.2% were non-families. 29.2% of all households were made up of individuals and 8.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.67 and the average family size was 3.37.[35]

The median income of its households was $37,862, and the median income of its families was $41,639. Males had a median income of $35,119 versus $30,494 for females. The per capita income for the city was $19,410. About 16.4% of families and 18.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 27.0% of those under age 18 and 17.5% of those age 65 or over.[35] One of the county's three homeless shelters, Lucy's Shelter, is located in Jersey City, though a growing community of homeless have made their home outside the transit station in Journal Square.[44]

The city is one of the most racially diverse in the world.[45] Jersey City has a large Kenyan community,[46] and the country's largest Egyptian Coptic population.[47] Indians make up a large part of the India Square district in Journal Square.[48] Pakistanis, Guyanese, Nigerians, Vietnamese, Chinese, Haitians, Polish, Italians and the Irish also make up a large percent of the population. Jersey City also hosts a Little Manila for the large Filipino population. The city is home to 4.4% of the state’s Hispanic population, and the highest number of mixed-race residents in the county at 13%.[49] However, relations between ethnic groups have not always been amicable, as evidenced by incidents such as the infamous Dotbusters gang attacks of 1987 against residents of South Asian descent.[50]

Government

Local government

The current mayor is Jerramiah Healy, who won the special election in 2004, and was later reelected in 2005 and 2009. The current Business Administrator (BA) is John "Jack" Kelly. Kelly was nominated by Mayor Healy and was approved by the city council with a 7–1 vote. He started as the BA on May 18, 2010.[51] The current City Clerk is Robert Byrne.

Jersey City is governed under the Faulkner Act (Mayor-Council) form of municipal government by a mayor and a nine-member city council. The city council consists of six members elected from wards and three elected at large, all elected to four-year terms on a concurrent basis in non-partisan elections.[52][53]

President At-large Kalimah Ahmad **term expires Nov 2011** (Democrat)

Radames “Ray” Velazquez, Jr. **term expires Nov 2011** (Democrat)Ward-level A (Greenville): Michael Sottolano (Democrat)

B (West Side): David Donnelly (Democrat)

C (Journal Square): Nidia Rivera Lopez (Democrat)

D (The Heights): William Gaughan (Democrat)

E (Downtown): Steven Fulop (Democrat)

F (Bergen/Lafayette): Viola Richardson (Democrat)Federal, state and county representation

The 9th, 10th, and 13th Congressional districts each contain portions of Jersey City. New Jersey's Ninth Congressional District is represented by Steve Rothman (D, Fair Lawn). New Jersey's Tenth Congressional District is represented by Donald M. Payne (D, Newark). New Jersey's Thirteenth Congressional District is represented by Albio Sires (D, West New York). New Jersey is represented in the United States Senate by Frank Lautenberg (D, Cliffside Park) and Bob Menendez (D, Hoboken).

Part of Jersey City is in the 31st District of the New Jersey Legislature, which is represented in the New Jersey Senate by Sandra Bolden Cunningham (D, Jersey City) and in the New Jersey General Assembly by Jason O'Donnell (D, Bayonne) and Charles Mainor (D, Jersey City).[54][55] Another portion of Jersey City is in the 32nd District, which is represented in the New Jersey Senate by Nicholas Sacco (D, North Bergen) and in the New Jersey General Assembly by Vincent Prieto (D, Secaucus) and Joan M. Quigley (D, Jersey City).[56] A third part of the city is in the 33rd Legislative District, which is represented in the New Jersey Senate by Brian P. Stack (D, Union City) and in the New Jersey General Assembly by Ruben J. Ramos (D, Hoboken) and Caridad Rodriguez (D, West New York).[57]

The city encompasses three Hudson County Freeholder districts in their entirety, while three others are shared with adjacent towns.The Hudson County Executive, elected at-large, is Thomas A. DeGise.[58] Hudson County Board of Chosen Freeholders Districts 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 8 are located partially or entirely in Jersey City. District 1 comprises neighboring Bayonne and a small part of Jersey City, Country Village,[59] and is represented by Doreen McAndrew DiDomenico.[60][61] District 2 includes the West Side and parts of the Marion Section and Journal Square[62] and is represented by William O'Dea.[60][61] District 3, which stretches from Paulus Hook through Bergen Hill to the east side of Greenville[63] is represented by Jeffrey Dublin.[60][61] District 4 includes Harsimus, Hamilton Park, and portions of Journal Square and the Heights [64] and is represented by Eliu Rivera.[60][61] District 5, comprising portions of the Heights and all of neighboring Hoboken,[65] is represented by Anthony Romano.[60][61] District 8 compromises all of North Bergen, the North End of Secaucus and the northern tip of the city near Transfer Station.[66] It is represented by Thomas Liggio.[60]

Emergency services

- Jersey City Fire Department

- Jersey City Police Department

- Port Authority of New York and New Jersey Police Department

- Hudson County Urban Search & Rescue

Neighborhoods

Neighborhoods in Jersey City, New Jersey Bergen-Lafayette

Downtown Exchange Place · Hamilton Park · Harsimus · Holland Tunnel · Pavonia Newport · Paulus Hook · Van Vorst Park · The Village · WALDO/PowerhouseGreenville The Heights Journal Square Meadowlands Upper New York Bay West Side Jersey City (and most of Hudson County) is located on the peninsula known as Bergen Neck, with a waterfront on the east at the Hudson River and New York Bay and on the west at the Hackensack River and Newark Bay. Its north-south axis corresponds with the ridge of Bergen Hill, the emergence of the Hudson Palisades.[67] The city is the site of some of the earliest European settlements in North America, which grew into each other rather expanding from central point.[68][69] This growth and the topograghy greatly influenced the development of the sections of the city[70][71] and the neighborhoods within them.[25] The city is divided into six wards.[53]

Downtown Jersey City

Downtown Jersey City is the area from the Hudson River westward to the Newark Bay Extension of the New Jersey Turnpike (Interstate 78) and the New Jersey Palisades; it is also bounded by Hoboken to the north and Liberty State Park to the south.

Newport and Exchange Place are redeveloped waterfront areas consisting mostly of residential towers, hotels and office buildings. Newport is a planned mixed-use community, built on the old Erie Lackawanna Railway yards, made up of residential rental towers, condominiums, office buildings, a marina, schools, restaurants, hotels, Newport Centre Mall, a waterfront walkway, transportation facilities, and on-site parking for more than 15,000 vehicles. Newport had a hand in the renaissance of Jersey City although, before ground was broken, much of the downtown area had already begun a steady climb (much like Hoboken). Some critics have derided the Newport development for its isolation because it is cut off from the rest of the city by the Newport Centre Mall and other big box retail. The Newport Centre area is also home of The Westin Hotel.[72]

Bergen-Lafayette

Bergen-Lafayette, formerly Bergen City, New Jersey, lies between Greenville to the south and McGinley Square to the north. It also borders Liberty State Park and Downtown to the east and the West Side. This area is commonly called "The Hill" by the natives of the city.Communipaw Avenue and Bergen Avenue are main thoroughfares. The former Jersey City Medical Center complex, a cluster of Art Deco buildings on a rise in the center of the city, are being converted into residential complexes called The Beacon.[73]

The Heights

The Heights or Jersey City Heights is a district in the north end of Jersey City atop the New Jersey Palisades overlooking Hoboken to the east and Croxton in the Meadowlands to the west.

The southern border of The Heights is generally considered to be north of Bergen Arches and The Divided Highway, while Paterson Plank Road in Washington Park is its main northern boundary. Transfer Station is just over the city line. Its postal area ZIP Code is 07307. The Heights mostly contains two- and three-family houses and low rise apartment buildings, and is similar to North Hudson architectural style and neighborhood character.

Previously the city of Hudson City, The Heights was incorporated into Jersey City in 1852.

Transportation

Hudson County Transportation Network Intermodal hubs Bergenline Station • Exchange Place • Hoboken Terminal • Journal Square • Newark Penn Station • Port Authority Bus Terminal • Weehawken Port Imperial • World Trade CenterTrain Hoboken Terminal • Hudson Bergen Light Rail • Meadowlands Rail Line • Port Authority Trans Hudson • Secaucus JunctionBus A&C Bus • Coach USA • Dollar van • GWB Plaza • New Jersey Transit routes 1-89 • New Jersey Transit routes to Manhattan, Bergen, and Passaic • Nungessers • Red and TanFerry Hoboken Terminal • Liberty Water Taxi • New York Waterway • Paulus Hook Ferry Terminal • Statue Cruises • Weehawken Port ImperialAirports Vehicular bridges

and tunnelsPassenger seaports Major thoroughfares Belleville Turnpike • Boulevard East • Jersey City-Newark Turnpike • Kennedy Boulevard • Paterson Plank Road • River Road • Schuyler Avenue • Tonnele Avenue • 14th Street ViaductHighways  In the immediate aftermath of the September 11, 2001 attacks many people were evacuated by ferry to Jersey City

In the immediate aftermath of the September 11, 2001 attacks many people were evacuated by ferry to Jersey City

Of all Jersey City commuters, 8.17% walk to work, and 46.62% take public transit. This is the second highest percentage of public transit riders of any city with a population of 100,000+ in the United States, behind only New York City and ahead of Washington, D.C. A significant minority of Jersey City households do not own an automobile.[74]

Rail

- Hudson-Bergen Light Rail: One of the most popular ways of transportation in the city. Twenty three stations in Bayonne, Hoboken, Jersey City, North Bergen, Union City, and Weehawken. Three branches: Hoboken-22nd Street, Hoboken-Tonnelle Avenue, and West Side Avenue-Tonnelle Avenue.

- PATH: 24-hour rapid transit system with four stations in Jersey City: Exchange Place, Newport, Grove Street, and Journal Square to Hoboken Terminal (HOB), midtown Manhattan (33rd) (along 6th Ave to Herald Square/Pennsylvania Station), World Trade Center (WTC), and Newark Penn Station (NWK).

- Hoboken Terminal-New Jersey Transit Hoboken Division: Main Line (to Suffern, and in partnership with MTA/Metro-North, express service to Port Jervis), Bergen County Line, and Pascack Valley Line, all via Secaucus Junction (where transfer is possible to Northeast Corridor Line); Montclair-Boonton Line and Morris and Essex Lines (both via Newark Broad Street Station); North Jersey Coast Line (limited service as Waterfront Connection via Newark Penn Station to Long Branch and Bay Head); Raritan Valley Line (limited service via Newark Penn Station).

Water

- NY Waterway ferries operate between Newport, Paulus Hook Ferry Terminal, Liberty Harbor, Port Liberté to Manhattan at Battery Park City Ferry Terminal, Pier 11-Wall Street, and West Midtown Ferry Terminal, where free transfer is available to a variety of "loop" buses.

- Statue Cruises provides service between Ellis Island and Liberty Island[75][76][77]

- Liberty Water Taxi operates ferries between Dock M. of Liberty State Park and the Battery Park City.[78]

Surface

The Journal Square Transportation Center, Exchange Place, and Hoboken Terminal (just over the city line's northeast corner) are major origination/destination points for buses. Service is available to numerous points within Jersey City, Hudson County, and some suburban areas as well as to Newark on the 1, 2, 6, 22, 43, 64, 67, 68, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 123, 125, 305, 319 and 981 lines.[79] Also serving Jersey City are various private lines operated by the Bergen Avenue and Montgomery & Westside IBOAs, and by Red & Tan in Hudson County.

Entrance to the Holland Tunnel which carries high amounts of vehicular traffic from New Jersey to Lower Manhattan.

Entrance to the Holland Tunnel which carries high amounts of vehicular traffic from New Jersey to Lower Manhattan.

They are usually referred to by natives as the "Immy".

Air

- Newark Liberty International Airport (EWR) is the closest of the metropolitan area's three major airports

- LaGuardia Airport (LGA) is in East Elmhurst, Queens

- John F. Kennedy International Airport (JFK) is on Jamaica Bay in Queens

- Teterboro Airport, in the Hackensack Meadowlands, serves private and corporate planes

- Newport Helistop Heliport at Hudson River at Newport[80]

Road

- Holland Tunnel: in downtown Jersey City with eastern terminus at Canal Street, Manhattan

- Highways include the New Jersey Turnpike Extension (Interstate 78), U.S. Routes 1 and 9, and New Jersey Routes 139 and 440.

A part of the East Coast Greenway, a planned unbroken bike route from Maine to the Florida Keys, will travel through the city. Both the Hudson River Waterfront Walkway and Hackensack RiverWalk are bicycle friendly.[81]

Education

Colleges and universities

Jersey City is home to the New Jersey City University (NJCU) and Saint Peter's College, both of which are located in the city's West Side district. It is also home to Hudson County Community College, which is located in Journal Square. The University of Phoenix has a small location at Newport, and Rutgers University offers MBA classes at Harborside Center. Often forgotten is Hudson County Community College, a junior college offering courses to help the transition into a larger university. Hudson County Community College is praised for the culinary department and program.

Public schools

The Jersey City Public Schools serve students 3 years and older from Pre-K 3 through twelfth grade. The district is one of 31 Abbott Districts statewide.[82]

Dr. Ronald E. McNair Academic High School was the top-ranked public high school in New Jersey out of 316 schools statewide, in New Jersey Monthly magazine's September 2006 cover story on the state's Top Public High Schools[83] and was selected as 15th best high school in the United States in Newsweek magazine's national 2005 survey.[84] William L. Dickinson High School is the oldest high school in the city and one of the largest schools in Hudson County in terms of student population. Opened in 1906 as the Jersey City High School it is one of the oldest school sites in the city, its a four-story Beaux-Arts building located on a hilltop facing the Hudson River. Liberty High School (New Jersey)is also one of the top schools in the heights. It's the only high school that focuses on all academics. Other public high schools in Jersey City are James J. Ferris High School, Lincoln High School, and Henry Snyder High School. The Hudson County Schools of Technology (which also has campuses in North Bergen and Secaucus) has a campus in Jersey City, which includes County Prep High School.[85]

Among Jersey City's elementary and middle schools is Academy I Middle School, which is part of the Academic Enrichment Program for Gifted Students. Another school is Alexander D. Sullivan P.S. #30, an ESL magnet school in the Greenville district, which services nearly 800 Pre-k through 5th grade students.[86]

Jersey City also has 12 charter schools, which are run under a special charter granted by the Commissioner of the New Jersey Department of Education, including the Mathematics, Engineering, Technology and Science Charter School (for grades 6 - 12) and the Dr. Lena Edwards Charter School (for K-8), which were approved in January 2011.[87]

Private schools

Catholic schools

The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Newark maintains a network of elementary and secondary Catholic schools serve every area of Jersey City. High schools administered by the Archdiocese are Hudson Catholic Regional High School, St. Anthony High School, Saint Dominic Academy and St. Peter's Preparatory School.[88] St. Mary High School - Closed in June 2011 due to declining enrollment[89]

Catholic grade schools include Our Lady of Mercy Academy, Our Lady of Czestochowa School, Resurrection School, Sacred Heart School, St. Aloysius Elementary Academy, St. Anne School, St. Joseph School and St. Nicholas School.[90]

Other private schools

Other private high schools in Jersey City include First Christian Pentecostal Academy and Stevens Cooperative School. Kenmare High School is operated through the York Street Project as part of an effort to reduce rates of poverty in households headed by women, through a program that offers small class sizes, individualized learning and development of life skills.[91]

A number of other charter and private schools are also available. Genesis Educational Center[92] is a private Christian school located in downtown Jersey City for ages newborn through 8th grade. The Jersey City Art School is a private art school located in downtown Jersey City for all ages.[93]

Museums and libraries

see also: Hudson County Exhibitions

The Jersey City Free Public Library has five regional branches, some of which have permanent collections and host exhibitions. At the Main Library, the New Jersey Room contains historical archives and photos. The Miller Branch is home to the Afro-American Historical and Cultural Society Museum. The Five Corners Branch specializes in works related to music and the fine arts, and is a gallery space. The library system also supports a bookmobile and five neighborhood libraries.[94]

Liberty State Park is home to Central Railroad of New Jersey Terminal, the Interpretive Center, and Liberty Science Center, an interactive science and learning center. The center, which first opened in 1993 as New Jersey's first major state science museum, has science exhibits, the world's largest IMAX Dome theater, numerous educational resources, and the original Hoberman sphere.[95] From the park ferries travel to both Ellis Island and the Immigration Museum and Liberty Island, site of The Statue of Liberty.[96]

The Jersey City Museum shows contemporary work and sponsors community-oriented projects. The Museum of Russian Art specializes in Soviet Nonconformist Art.

Some stations of the Hudson Bergen Light Rail, including those at Exchange Place, Danforth Avenue, and Martin Luther King Drive station,[97] have educational public art exhibitions.

Commerce

Jersey City has several shopping districts, some of which are traditional main streets for their respective neighborhoods, such as Central, Danforth, and West Side avenues. Journal Square is a major commercial district. Newport Mall is a regional shopping area.[98] Portions of the city are part of an Urban Enterprise Zone. In addition to other benefits to encourage employment within the Zone, shoppers can take advantage of a reduced 3½% sales tax rate (versus the 7% rate charged statewide).[99]

Jersey City is home to the headquarters of Verisk Analytics.[100] and Lord Abbett, a privately held money management firm.[101] Companies such as Computershare, ICAP, ADP, and Fidelity Investments also conduct operations in the city.[102]

Media

Jersey City is located within the New York media market, most of its daily papers available for sale or delivery. The daily newspaper The Jersey Journal, located at its namesake Journal Square, covers Hudson County, its morning daily, Hudson Dispatch now defunct.[103] The Jersey City Reporter is part of the Hudson Reporter group of local weeklies. The Jersey City Independent is a web-only news outlet that covers politics and culture in the city. The River View Observer is another weekly published in the city and distributed throughout the county. Another county wide weekly, El Especialito, also serves the city.[104] The Daily News maintains extensive publishing and distribution facilities at Liberty Industrial Park.[105]

WFMU 91.1FM (WMFU 90.1FM in the Hudson Valley), the longest running freeform radio station in the US, moved to Jersey City in 1998.[106] WSNR is also licensed in the city.

Notable landmarks

- See Etymologies of place names in Hudson County, New Jersey

- See Historic districts in Hudson County, New Jersey

- See List of cemeteries in Hudson County, New Jersey

- See List of bridges, tunnels, and cuts in Hudson County, New Jersey

- See List of Registered Historic Places in Hudson County, New Jersey

- Statue of Liberty National Monument, Ellis Island and Liberty Island

- Liberty Science Center

- The Katyń Memorial by well-known Polish-American artist Andrzej Pitynski on Exchange Place is the first memorial of its kind to be raised on American soil to honor the dead of the Katyń Forest Massacre.[107]

- The Colgate Clock, promoted by Colgate-Palmolive as the largest in the world, sits in Jersey City and faces Lower New York Bay and Lower Manhattan (it is clearly visible from Battery Park in lower Manhattan). The clock, which is 50 feet (15 m) in diameter with a minute hand weighing 2,200 pounds, was erected in 1924 to replace a smaller one that was relocated to a plant in Jeffersonville, Indiana.[108]

Notable residents

See also

- Timeline of Jersey City area railroads

- Historic Jersey City & Harsimus Cemetery

- Hudson River Waterfront Walkway

- Hackensack RiverWalk

- Demographics of New Jersey

- St. Mark Coptic Orthodox Church

- Gateway Region

- Gold Coast, New Jersey

- Bergen Township

References

- ^ Kaulessar, Ricardo (April 15, 2005). "Why do people call Jersey City ‘Chilltown’?". Jersey City Reporter. http://hudsonreporter.com/view/full_story/2404239/article-Why-do-people-call-Jersey-City--Chilltown--Residents-shed-light-on-origin-of-rap-nickname?. Retrieved February 19, 2010.

- ^ "Jersey City: "Wall Street West"". BusinessWeek. October 29, 2001. http://www.businessweek.com/magazine/content/01_44/b3755057.htm. Retrieved February 19, 2010.

- ^ 2011 New Jersey Mayors Directory, New Jersey Department of Community Affairs. Accessed September 4, 2011.

- ^ Department of Business Administration, City of Jersey City. Retrieved July 26, 2010.

- ^ a b GCT-PH1. Population, Housing Units, Area, and Density: 2000 for Hudson County, New Jersey -- County Subdivision and Place, United States Census Bureau. Accessed September 5, 2011.

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Jersey City, Geographic Names Information System. Retrieved January 4, 2008.

- ^ a b c Hayes, Melissa. "2010 Census road tour stops in Jersey City", NJ.com/The Jersey Journal, January 5, 2010

- ^ Look Up a ZIP Code, United States Postal Service. Accessed September 5, 2011.

- ^ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. http://factfinder.census.gov. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ^ A Cure for the Common Codes: New Jersey, Missouri Census Data Center. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. http://geonames.usgs.gov. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ^ Strunsky, Steve (December 9, 2001). "CITIES; Bright Lights, Big Retail". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2001/12/09/nyregion/cities-bright-lights-big-retail.html.

- ^ Holusha, John. "Commercial Property / The Jersey Riverfront; On the Hudson's West Bank, Optimistic Developers", The New York Times, October 11, 1998. Accessed May 25, 2007. "'That simply is out of the question in midtown,' he said, adding that some formerly fringe areas in Midtown South that had previously been available were filled up as well. Given that the buildings on the New Jersey waterfront are new and equipped with the latest technology and just a few stops on the PATH trains from Manhattan, they become an attractive alternative. 'It's the sixth borough', he said."

- ^ Belson, Ken (May 21, 2007). "In Stamford, a Plan to Rebuild an Area and Build an Advantage". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2007/05/21/nyregion/21stamford.html.

- ^ Jersey City Past and Present: Pavonia, New Jersey City University. Accessed May 10, 2006.

- ^ A Virtual Tour of New Netherland, New Netherland Institute. Accessed May 10, 2006.

- ^ Ellis, Edward Robb (1966). The Epic of New York City. Old Town Books. p. 38.

- ^ Jersey City's Oldest House, Jersey City History. Retrieved September 11, 2007.

- ^ Zinsli, Christopher. "Jersey City's Underground Railroad history: Thousands of former slaves sought freedom by passing through Jersey City", Hudson Reporter, March 23, 2007. Accessed September 5, 2011. "New Jersey alone had as many as four main routes, all of which converged in Jersey City.... As the last stop in New Jersey before fugitive slaves reached New York, Jersey City played an integral role - by some estimates, more than 60,000 escaped slaves traveled through Jersey City."

- ^ a b c "The Story of New Jersey's Civil Boundaries: 1606–1968", John P. Snyder, Bureau of Geology and Topography; Trenton, New Jersey; 1969. p. 146-147.

- ^ "Municipal Incorporations of the State of New Jersey (according to Counties)" prepared by the Division of Local Government, Department of the Treasury (New Jersey); December 1, 1958, p. 78 – Extinct List.

- ^ "Federal Bureau of Investigation – Press Room – Headline Archives". Fbi.gov. July 30, 1916. http://www.fbi.gov/page2/july04/blacktom073004.htm. Retrieved June 10, 2010.

- ^ Alexander, Jack (October 26, 1940). "King Hanky-Panky of Jersey City". The Saturday Evening Post: p. 122

- ^ a b "Hague's End". TIME. May 23, 1949.

- ^ a b Grundy, J. Owen (1975). The History of Jersey City (1609–1976). Jersey City: Walter E. Knight.

- ^ "Hudson County's Degradation. Where Official Corruption Runs Riot is Not Concealed." The New York Times, October 22, 1893

- ^ Strum, Charles. "Another Milepost on the Long Trail of Corruption in Hudson County" The New York Times; December 19, 1991

- ^ Strunsky, Steve. "Why Can't Hudson County Get Any Respect?; Despite Soaring Towers, Rising Property Values and Even a Light Rail, the Region Struggles to Polish Its Image" The New York Times, January 14, 2001

- ^ " A City Whose Time Has Come Again" The New York Times, April 30, 2000.

- ^ Hudson-Bergen Light Rail schedule (PDF)

- ^ Healy, Jerramiah. "Renaissance on the Waterfront and Beyond: Jersey City's Reach for the Stars". New Jersey State League of Municipalities.

- ^ Campbell Gibson (June 1998). "Population of the 100 Largest Cities and Other Urban Places in The United States: 1790 TO 1990". U.S. Census Bureau. http://www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/twps0027.html. Retrieved March 6, 2007.

- ^ Wm. C. Hunt, Chief Statistician for Population. "Fourteenth Census of The United States: 1920; Population: New Jersey; Number of inhabitants, by counties and minor civil divisions" (ZIP). U.S. Census Bureau. http://www2.census.gov/prod2/decennial/documents/41084506no553.zip. Retrieved March 21, 2007.

- ^ "New Jersey Resident Population by Municipality: 1930–1990". Archived from the original on March 22, 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20070322215919/http://www.wnjpin.net/OneStopCareerCenter/LaborMarketInformation/lmi01/poptrd6.htm. Retrieved March 3, 2007.

- ^ a b c d Census 2000 Demographic Profile Highlights: Jersey City city, New Jersey, United States Census Bureau. Accessed September 5, 2011.

- ^ The Counties and Most Populous Cities and Townships in 2010 in New Jersey: 2000 and 2010, United States Census Bureau. Accessed November 7, 2011.

- ^ The Counties and Most Populous Cities and Townships in 2010 in New Jersey: 2000 and 2010, United States Census Bureau. Accessed September 3, 2011. HTML version of original Excel spreadsheet.

- ^ Hunger, Matt (June 16, 2011). "Jersey City Hires Outside Firm to Help Challenge 2010 Census Count". Jersey City Independent. http://www.jerseycityindependent.com/2011/06/16/jersey-city-hires-outside-firm-to-help-challenge-2010-census-count/. Retrieved 2011-06-06.

- ^ MacDonald, Terrence (June 16, 2011), "Jersey City paying consultant $25,000 to challenge Census count", The Jersey Journal, http://www.nj.com/hudson/index.ssf/2011/06/jersey_city_paying_consultant.html, retrieved 2011-06-18

- ^ Hunger, Matt (September 2, 2011), "Firm’s Preliminary Findings Say 2010 Census Count Missed 19,000 Housing Units in Jersey City", Jersey City Independent, http://www.jerseycityindependent.com/2011/09/01/firms-preliminary-findings-say-2010-census-count-missed-19000-units-in-jersey-city/, retrieved 2011-09-02

- ^ Cities with 100,000 or More Population in 2000 ranked by Population, 2000 in Rank Order, United States Census Bureau. Accessed September 5, 2011.

- ^ Cities with 100,000 or More Population in 2000 ranked by Population per Square Mile, 2000 in Rank Order, United States Census Bureau. Accessed September 5, 2011.

- ^ Jersey City, New Jersey, City-Data. Retrieved January 24, 2008.

- ^ Wright, E. Assata. "Three deaths raise concerns". The Union City Reporter. July 31, 2001

- ^ Clapper, Tara. "Top 100 Racially-Diverse Cities List Includes New York and New Jersey Cities", Home Space, accessed January 19, 2011.

- ^ http://www.kisii.com/

- ^ www.bcnychurchplanting.org/uploaded_files/Egyptian%20Profile.pdf

- ^ www.getnj.com/jerseycity/jclittleindia.shtml

- ^ Cullen, Deanna. “Growing influence”, The Union City Reporter, February 13, 2011, pages 1 and 15

- ^ Marriott, Michel. "In Jersey City, Indians Protest Violence", The New York Times, October 12, 1987. Accessed October 6, 2008. "But in recent weeks, Indians here say, the violence has taken on a new and uglier cast. One Jersey City Indian was beaten to death in Hoboken. Another remains in a coma after being discovered beaten unconscious on a busy street corner here earlier this month. And in a crudely handwritten letter, partially printed in The Jersey Journal, someone wrote, We will go to any extreme to get Indians to move out of Jersey City. The note was signed The Dotbusters."

- ^ http://www.jerseycityindependent.com/2010/05/14/council-report-a-new-ba-litter-patrol-dustup-police-and-fire-contracts-and-more/

- ^ 2005 New Jersey Legislative District Data Book, Rutgers University Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy, April 2005, p. 139.

- ^ a b "JC Ward map". Jerseycityindependent.com. January 6, 2009. http://www.jerseycityindependent.com/2009/01/06/jersey-city-ward-map/. Retrieved June 10, 2010.

- ^ "Legislative Roster: 2010-2011 Session". New Jersey Legislature. http://www.njleg.state.nj.us/members/roster.asp. Retrieved 2010-02-08.

- ^ Hester, Sr., Tom. "Bayonne Democratic chief Jason O'Donnell named to Assembly seat". newjerseynewsroom.com. http://www.newjerseynewsroom.com/state/bayonne-democratic-chief-jason-odonnell-named-to-assembly-seat. Retrieved February 15, 2011.

- ^ "Legislative Roster: 2010-2011 Session". New Jersey Legislature. http://www.njleg.state.nj.us/members/roster.asp. Retrieved 2010-02-08.

- ^ "Legislative Roster: 2010-2011 Session". New Jersey Legislature. http://www.njleg.state.nj.us/members/roster.asp. Retrieved 2010-07-05.

- ^ Thomas A. Degise, Hudson County Executive, Hudson County, New Jersey. Accessed January 5, 2011.

- ^ Freeholder District 1, Hudson County, New Jersey. Accessed January 15, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f Bichao, Sergio (June 03, 2008). "Hudson County results". nj.com. http://www.nj.com/elections/index.ssf/2008/06/hudson_county_results.html. Retrieved 2011-01-15.

- ^ a b c d e Freeholder Biographies, Hudson County, New Jersey. Accessed January 15, 2011.

- ^ Freeholder District 2, Hudson County, New Jersey. Accessed January 15, 2011.

- ^ Freeholder District 3, Hudson County, New Jersey. Accessed January 15, 2011.

- ^ Freeholder District 4, Hudson County, New Jersey. Accessed January 15, 2011.

- ^ Freeholder District 5, Hudson County, New Jersey. Accessed January 15, 2011.

- ^ Freeholder District 8, Hudson County, New Jersey. Accessed January 15, 2011.

- ^ Hudson County New Jersey Street Map. Hagstrom Map Company, Inc. 2008. ISBN 0-8809-7763-9.

- ^ Lynch, Kevin (June 1960). Images of the City. MIT. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-262-62001-7. http://books.google.com/?id=_phRPWsSpAgC&pg=PA26&lpg=PA26&dq=hudson+boulevard+bergen&q=hudson%20boulevard%20bergen.

- ^ Gabrielan, Randall (1999), Jersey City in Vintage Postcards, Arcadia Publishing, ISBN 978-0-7385-4954-5, http://books.google.nl/books?id=i6R71oZI6-gC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Jersey+City:+In+Vintage+Postcards&hl=nl&ei=MA2cTZH_D9CgOoPEtI0H&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CD0Q6AEwAA#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ^ Christine Lagorio (January 11, 2005). "Village Voice 01/011/2005". Villagevoice.com. http://www.villagevoice.com/2005-01-11/nyc-life/close-up-on-the-jersey-city-waterfront/. Retrieved June 10, 2010.

- ^ "The New Jersey Suburbs How New York is Extending on the West Side of the Hudson". New York Times. April 22, 1872. http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?res=F40617F73C5D1A7493C0AB178FD85F468784F9. Retrieved 2011-02-20.

- ^ Goldberger, Paul (Aungust 2, 2004). "Shanghai on the Hudson". The New Yorker. http://www.newyorker.com/archive/2004/08/02/040802crsk_skyline

- ^ Model of urban future: Jersey City?, USA Today, April 15, 2007.

- ^ http://www.bikesatwork.com/carfree/carfree-census-database.html

- ^ Ellis Island and Liberty Island Ferry Map

- ^ Statue of Liberty & Ellis Island information at Star Cruises; Accessed August 31, 2010

- ^ "Hornblower Cruises". Statuecruises.com. http://statuecruises.com/ferry-service/welcome.aspx. Retrieved June 10, 2010.

- ^ "Jersey City Public Transportation Information". Jctransit.com. http://jctransit.com/Ferry/Default.aspx. Retrieved June 10, 2010.

- ^ Hudson County Bus / Rail Connections, New Jersey Transit, backed up by the Internet Archive as of May 25, 2009. Accessed September 5, 2011.

- ^ "Newport Helistop Heliport". RunwayFinder. http://www.runwayfinder.com/airport/91nj/. Retrieved June 10, 2010.

- ^ "Easy Riders JC". Easy Riders JC. http://www.EasyRidersJC.com. Retrieved June 10, 2010.

- ^ Abbott Districts, New Jersey Department of Education. Retrieved March 31, 2008.

- ^ Top Public High Schools in New Jersey[dead link], New Jersey Monthly, September 2006

- ^ Top 1000 High Schools in The United States[dead link], Newsweek August 5, 2005.

- ^ High Schools, Hudson County Schools of Technology. Accessed November 16, 2011.

- ^ "Alexander D. Sullivan School at Jersey City Board of Education". Jcboe.org. http://www.jcboe.org/schools/ps-30.aspx. Retrieved June 10, 2010.

- ^ Staff. "State approves 2 new Jersey City charter schools", The Jersey Journal, January 19, 2011. Accessed November 16, 2011.

- ^ Hudson County High Schools, Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Newark. Accessed September 2, 2011.

- ^ Persaud, Vishal. "Announcement St. Mary High School in Jersey City will close in June has some parents, students and staff stunned", The Jersey Journal, February 9, 2011. Accessed September 2, 2011. "Parents, students and staff at St. Mary High School in Jersey City remained stunned yesterday by Monday's news that the school is closing at the end of June.... St. Mary will graduate 72 seniors in June, which would have put the school's enrollment at 93 among the remaining classes. Ten years ago, St. Mary had 381 students, Lalicato said. At its peak in the mid-1980s, the school had more than 450 students."

- ^ Hudson County Elementary Schools, Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Newark. Accessed September 2, 2011.

- ^ Who We Are: Kenmare High School, The York Street Project. Accessed September 2, 2011.

- ^ "Genesis Educational Center". Riversidecares.org. http://www.riversidecares.org. Retrieved June 10, 2010.

- ^ "The Jersey City Art School". Jcartschool.com. http://www.jcartschool.com. Retrieved June 10, 2010.

- ^ Net Ops. "JC Free Public Library". Jclibrary.org. http://www.jclibrary.org/. Retrieved June 10, 2010.

- ^ LSP[dead link]

- ^ LSP Ferry Service[dead link]

- ^ "MLK Station". Subwaynut.com. http://www.subwaynut.com/hblr/mlk_drive/index.php. Retrieved June 10, 2010.

- ^ "JC Shopping Districts". Jerseycityonline.com. http://www.jerseycityonline.com/jersey_city_shopping_districts.htm. Retrieved June 10, 2010.

- ^ Geographic & Urban Redevelopment Tax Credit Programs: Urban Enterprise Zone Employee Tax Credit, State of New Jersey, backed up by the Internet Archive as of May 25, 2009. Accessed September 5, 2011.

- ^ Todd, Susan. "Verisk Analytics of Jersey City raises $1.9B in stock offering", The Star-Ledger, October 8, 2009. Accessed October 8, 2009.

- ^ Lord Abbett: Contact Us, accessed April 2, 2011.

- ^ Major Employer's List, Hudson County Economic Development Corporation, accessed March 18, 2011.

- ^ Staff. "Owners Warn That Hudson County Newspaper Could Be Closed", The New York Times, January 3, 2002. Accessed September 5, 2011.

- ^ "El Especial". El Especial. http://www.elespecial.com/. Retrieved June 10, 2010.

- ^ "City data Jersey City Economy". City-data.com. http://www.city-data.com/city/Jersey-City-New-Jersey.html. Retrieved June 10, 2010.

- ^ WFMU. "About WFMU FAQ". Wfmu.org. http://wfmu.org/about.shtml. Retrieved June 10, 2010.

- ^ Stoltzfus, Duane (June 6, 1991). "Statue Erected as Memorial to Victims of Katyn Massacre". The Record.

- ^ Lyons, Richard (July 9, 1989). "Jersey City Landmark; Now It's Time to Move the Colgate Clock". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/1989/07/09/realestate/postings-jersey-city-landmark-now-it-s-time-to-move-the-colgate-clock.html?pagewanted=1. Retrieved January 30, 2010.

External links

Municipalities and communities of Hudson County, New Jersey Cities Bayonne | Hoboken | Jersey City | Union City

Borough Towns Guttenberg | Harrison | Kearny | Secaucus | West New York

Townships  State of New Jersey

State of New JerseyTopics Regions - Atlantic Coastal Plain

- Central Jersey

- Delaware River Region

- Delaware Valley

- Gateway Region

- Gold Coast

- Highlands

- Jersey Shore

- Meadowlands

- New York metro area

- North Hudson

- North Jersey

- Pascack Valley

- Piedmont

- Pine Barrens

- Raritan Bayshore

- Ridge-and-Valley Appalachians

- Southern Shore Region

- Skylands Region

- South Jersey

- Tri‑State Region

- West Hudson

Counties Major cities Mayors of cities with populations exceeding 100,000 in New Jersey - Jerramiah Healy

(Jersey City)

- Joey Torres

(Paterson)

- Chris Bollwage

(Elizabeth)

State capital: Tony Mack (Trenton)

State capital: Tony Mack (Trenton)

Other states: AL • AK • AZ • AR • CA • CO • CT • DE • FL • GA • HI • ID • IL • IN • IA • KS • KY • LA • ME • MD • MA • MI • MN • MS • MO • MT • NE • NV • NH • NJ • NM • NY • NC • ND • OH • OK • OR • PA • RI • SC • SD • TN • TX • UT • VT • VA • WA • WV • WI • WYCategories:- Populated places in Hudson County, New Jersey

- Faulkner Act Mayor-Council

- Jersey City, New Jersey

- New Jersey Meadowlands District

- New Jersey Urban Enterprise Zones

- Populated places established in 1633

- County seats in New Jersey

- Cities in New Jersey

- Populated places on the Hudson River

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.