- Pennsylvania Station (New York City)

-

New York

Pennsylvania Station

Entrance, with Madison Square Garden and Penn Plaza in the background.Station statistics Address 8th Ave & 31st St, New York, NY 10001

7th Ave & 8th Ave between 31st St & 33rd StCoordinates 40°45′02″N 73°59′38″W / 40.750638°N 73.993899°WCoordinates: 40°45′02″N 73°59′38″W / 40.750638°N 73.993899°W Lines Amtrak: AdirondackCardinalCarolinianPennsylvanianSilver StarLong Island Rail Road: New Jersey Transit:ACESConnections New York City Subway (Both 34th Street – Penn Stations)

at IRT Broadway – Seventh Avenue Line

at IRT Broadway – Seventh Avenue Line

at IND Eighth Avenue Line

at IND Eighth Avenue Line

MTA NYC Bus: M4, M7, M20, M34 / M34A Select Bus Service, Q32

MTA NYC Bus: M4, M7, M20, M34 / M34A Select Bus Service, Q32

Atlantic Express: X23, X24

Atlantic Express: X23, X24

Megabus: M21, M22, M23, M24, M27

Megabus: M21, M22, M23, M24, M27

Greyhound Lines: BoltBus and NeOn

Greyhound Lines: BoltBus and NeOn

Eastern Shuttle

Eastern Shuttle

New York Airport Service: Thruway Motorcoach service to airports

New York Airport Service: Thruway Motorcoach service to airportsPlatforms 11 Tracks 21 Baggage check Available for Carolinian, Crescent, Lake Shore Limited, Northeast Regionals 66 and 67, Palmetto, Silver Meteor and Silver Star trains Other information Opened 1910 Rebuilt 1964 Accessible

Code NYP Owned by Amtrak Fare zone City Terminal Zone (LIRR)

Zone 1 (New Jersey Transit)Traffic Passengers (2010) 79,891 Average weekday[1]  1.2% (NJT)

1.2% (NJT)Passengers (2010) 8.378 million Annually[2]  7% (Amtrak)

7% (Amtrak)Passengers (2011) 231,140 Average weekday[3] (LIRR) Services Preceding station Amtrak Following station toward Washington, D.C.Acela Express Stamfordtoward Boston South StationVermonter Stamfordtoward St. Albanstoward Newport News or LynchburgNortheast Regional toward Boston South Station or Springfieldtoward ChicagoCardinal Terminus toward CharlotteCarolinian toward New OrleansCrescent toward HarrisburgKeystone Service toward PittsburghPennsylvanian toward SavannahPalmetto toward MiamiSilver Meteor Silver Star toward MontrealAdirondack toward Niagara Falls, NYEmpire Service toward RutlandEthan Allen Express toward TorontoMaple Leaf toward ChicagoLake Shore Limited LIRR Terminus Main Line

(City Terminal Zone)toward Long IslandNJ Transit Rail toward Atlantic CityACES Terminus toward TrentonNortheast Corridor Line toward Bay HeadNorth Jersey Coast Line toward HackettstownMontclair-Boonton Line Morristown Line toward GladstoneGladstone Branch Pennsylvania Station—commonly known as Penn Station—is the major intercity train station and a major commuter rail hub in New York City. It is one of the busiest rail stations in the world, and a hub for inbound and outbound railroad traffic in New York City. The New York City Subway system also has multiple lines that connect to the station. The station is in the underground levels of Pennsylvania Plaza, an urban complex between Seventh Avenue and Eighth Avenue and between 31st Street and 33rd Street in Midtown Manhattan, and is owned by Amtrak. Serving 300,000 passengers a day (compared to 140,000 across town at Grand Central Terminal) at a rate of up to a thousand every 90 seconds,[4] it is the busiest passenger transportation facility in the United States[5] and by far the busiest train station in North America.[6][7]

Penn Station is at the center of the Northeast Corridor, an electrified passenger rail line extending south to Washington, D.C., and north to Boston. Intercity trains are operated by Amtrak, while commuter rail services are operated by the Long Island Rail Road and New Jersey Transit. The station is also served by six New York City Subway routes.

Penn Station saw 8.4 million Amtrak passenger arrivals and departures in 2010, about double the traffic at the next busiest station, Union Station in Washington, D.C.[8] Penn Station's assigned IATA airport code is ZYP.[9] Its Amtrak and NJ Transit station code is NYP.

Contents

Services

Amtrak

Main article: AmtrakAmtrak owns the station and uses it for the following services:

- Acela Express to Boston, Providence, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington

- Adirondack to Montréal

- Cardinal to Philadelphia, Washington, Cincinnati, and Chicago

- Carolinian to Philadelphia, Washington, Richmond, Raleigh, and Charlotte

- Crescent to Philadelphia, Washington, Greensboro, Atlanta, and New Orleans

- Empire Service to Yonkers, Croton-Harmon, Poughkeepsie, Rhinecliff, Hudson, Albany, Schenectady, Amsterdam, Utica, Rome, Syracuse, Rochester, Buffalo, and Niagara Falls

- Ethan Allen Express to Albany and Rutland

- Keystone Service to Philadelphia, Lancaster, and Harrisburg

- Lake Shore Limited to Albany, Syracuse, Rochester, Buffalo, Cleveland, Toledo, and Chicago

- Maple Leaf to Albany, Syracuse, Rochester, Buffalo, and Toronto

- Pennsylvanian to Philadelphia, Harrisburg, and Pittsburgh

- Northeast Regional to Boston, Providence, New Haven, Trenton, Philadelphia, Wilmington, Baltimore, Washington, Richmond, and Newport News

- Palmetto, Silver Meteor and Silver Star to Philadelphia, Washington, Savannah, Jacksonville, Tampa, and Miami

- Vermonter to New Haven, Springfield, and St. Albans

ClubAcela Lounge

ClubAcela is a private lounge located on the Amtrak concourse (8th Avenue side of the station). Prior to December 2000 it was known as the Metropolitan Lounge. Guests are provided with comfortable seating, complimentary non-alcoholic beverages, newspapers, television sets and a conference room. Access to ClubAcela is restricted to the following passenger types:[10]

- Amtrak Guest Rewards members with a valid Select Plus member card.

- Amtrak passengers with a same-day ticket (departing) or ticket receipt (arriving) in First class or sleeping car accommodations.

- Complimentary ClubAcela Single-Day Pass holders.

- Continental Airlines President's Club Members with a valid card or passengers with a same-day travel ticket on Continental Business First class.

- Private rail car owners/lessees. The PNR number must be given to a Club representative upon entry.

Metropolitan Transportation Authority

Main article: Metropolitan Transportation Authority (New York)Penn Station is a major public transit hub as a result of the MTA bus system, the NYTCA subway and Long Island commuter rail service. Penn offers offers these MTA services:

- Long Island Rail Road (to Woodside station and points east)

- New York City Subway

- From Penn Station:

- From Herald Square, one block east at Sixth Avenue:

- New York City Transit buses:

- M4 (Fifth and Madison Avenues/Broadway/Fort Washington Avenue): Northbound only to West 193rd Street-Fort Washington Avenue, Washington Heights (or the Cloisters Museum in Fort Tryon Park).

- M7 (Lenox, Columbus, Amsterdam, Sixth and Seventh Avenues): southbound to West 14th Street-6th Avenue, Greenwich Village, via 7th Avenue; or northbound to West 147th Street-Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard, Harlem, via 6th Avenue.

- M16 (34th Street Crosstown): Westbound to Port Authority Bus Terminal; or eastbound to Waterside Plaza, Kips Bay.

- M20 (Seventh and Eighth Avenues/Varick and Hudson Streets): Northbound to Lincoln Center via Eighth Avenue; or southbound to South Ferry via Seventh Avenue.

- M34 (34th Street Crosstown): Westbound to Jacob K. Javits Convention Center; or eastbound to FDR Drive.

- Q32 (Fifth and Madison Avenues): Northbound only, to 81st Street and Northern Boulevard in Jackson Heights, Queens.

New Jersey Transit

Main article: New Jersey Transit- Montclair-Boonton Line to Montclair, with connecting service to Hackettstown

- Morris and Essex Lines to Summit and Dover or Gladstone

- Northeast Corridor Line to Trenton

- North Jersey Coast Line to Long Branch, with connecting service to Bay Head

- Atlantic City Express Service (ACES) to Atlantic City.

Passengers can transfer at Secaucus Junction to Main Line, Bergen County Line, and Pascack Valley Line trains, as well as Meadowlands Rail Line event service.

Passengers can transfer at Newark (Penn Station) to Raritan Valley Line trains.

PATH

Main article: Port Authority Trans-HudsonPort Authority Trans-Hudson (PATH) service to Hoboken and Jersey City, New Jersey does not technically serve Penn Station, but is located only a block away, at 33rd Street and Sixth Avenue. It was once accessible via underground passageway, but this has been closed to the public for security reasons, and now the only access is via the surface streets.

Continental Airlines

Continental Airlines operates a ticketing counter in the Amtrak section.[11]

BoltBus

BoltBus is a discount bus company owned and operated through a 50/50 partnership between Greyhound and Peter Pan bus lines. They operate intercity bus service from two stops at Pennsylvania Station (New York City). The company is best known for its Bolt for a Buck $1 fare promotion.

Penn Station Bus Stop #1 (West 33rd Street and 7th Avenue)

- Service to Penn Station, Baltimore, Maryland

- Service to Metrorail Intermodal Station, Greenbelt, Maryland

- Service to Union Station, Washington, D.C.

- Service to 10th Street and H Street NW, Washington, D.C.

Penn Station Bus Stop #2 (West 34th Street and 8th Avenue)

- Service to South Station (Gate #9), Boston, Massachusetts

- Service to Cherry Hill Mall, Cherry Hill, New Jersey

- Service to 30th Street Station, 30th Street between Market & Chestnut Streets, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Vamoose Bus

Vamoose Bus is a privately owned company providing transportation from their stop outside of Penn Station to the Washington DC area.

Penn Station bus stop (West 31st Street and 7th Avenue)

- Service to Bethesda Station, Bethesda, MD

- Service to Rosslyn Station, Arlington, VA

- Service to Lorton VRE Station, Lorton, VA

History

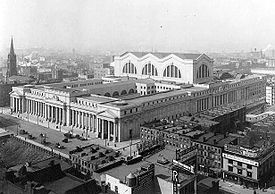

Pennsylvania Station is named for the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR), its builder and original tenant, and shares its name with several stations in other cities. The current facility is the substantially remodeled underground remnant of a much grander structure designed by McKim, Mead, and White and completed in 1910. The original Pennsylvania Station was an outstanding masterpiece of the Beaux-Arts style and one of the architectural jewels of New York City. The station's air rights were optioned in the 1950s. The option was executed soon after. The option called for the demolition of the head-house and train shed, to be replaced by an office complex and a new sports complex. The tracks of the station, which were well below street level, would remain untouched. Demolition began in October 1963. The Pennsylvania Plaza complex, including the fourth and current Madison Square Garden, was completed in 1968.

Planning and construction

Main article: New York Tunnel ExtensionUntil the early 20th century, PRR's rail network terminated on the western side of the Hudson River (once known locally as the North River) at Exchange Place in Jersey City, New Jersey. Manhattan-bound passengers boarded ferries to cross the Hudson River for the final stretch of their journey. The rival New York Central Railroad's line ran down Manhattan from the north under Park Avenue and terminated at Grand Central Terminal at 42nd St.

The Pennsylvania Railroad considered building a rail bridge across the Hudson, but the state required such a bridge to be a joint project with other New Jersey railroads, who were not interested.[12][13] The alternative was to tunnel under the river, but steam locomotives probably could not use such a tunnel, and in any case the New York State Legislature had prohibited steam locomotives in Manhattan after 1 July 1908.[14] The development of the electric locomotive at the turn of the 20th century, however, made feasible the construction of a tunnel. On December 12, 1901 PRR president Alexander Cassatt announced the railroad's plan to enter New York City by tunneling under the Hudson and building a grand station on the West Side of Manhattan south of 34th Street.

Beginning in June 1903, the North River Tunnels, two single-track tunnels, were bored from the west under the Hudson River and four single-track tunnels were bored from the east under the East River. This second set of tunnels linked the new station to Queens and the Long Island Rail Road, which came under PRR control (see East River Tunnels), and Sunnyside Yard in Queens, where trains would be maintained and assembled. Electrification was initially 600 volts DC–third rail, later changed to 11,000 volts AC–overhead catenary, when electrification of PRR's mainline was eventually extended to Washington, D. C. in the early 1930s.[12]

The tunnel technology was so innovative that in 1907 the PRR shipped an actual 23-foot (7.0 m) diameter section of the new East River Tunnels to the Jamestown Exposition near Norfolk, Virginia, to celebrate the 300th anniversary of the founding of the colony at Jamestown. The same tube, with an inscription indicating that it had been displayed at the Exposition, was later installed under water and remains in use today. Construction was completed on the Hudson River tunnels on October 9, 1906, and on the East River tunnels March 18, 1908. Meanwhile, ground was broken for Pennsylvania Station on May 1, 1904. By the time of its completion and the inauguration of regular through train service on Sunday, November 27, 1910, the total project cost to the Pennsylvania Railroad for the station and associated tunnels was $114 million (approximately $2.5 billion in 2007 dollars), according to an Interstate Commerce Commission report.[15]:156-7

The railroad paid tribute to Cassatt, who did not live to see the completion of his great edifice:

Alexander Johnston CassattPresident, Pennsylvania Railroad Company 1899–1906

Whose Foresight, Courage and Ability achieved the extension of the Pennsylvania Railroad into New York City—Inscription on statue of Alexander Cassatt in Pennsylvania Station (1910)[12]Occupying two complete city blocks from Seventh Avenue to Eighth Avenue and from 31st to 33rd Streets, Pennsylvania Station when completed covered an area of 8 acres (3.2 ha) and was one of the first rail terminals to separate arriving from departing passengers on two different concourses.[15]:151

Original structure (1910–1963)

The original structure was made of pink granite and was marked by an imposing, sober colonnade of Doric columns. The colonnades embodied the sophisticated integration of multiple functions and circulation of people and goods. McKim, Mead and White's Pennsylvania Station combined frank glass-and-steel train sheds and a magnificently proportioned concourse with a breathtaking monumental entrance to New York City. From the street, twin carriageways, modelled after Berlin's Brandenburg Gate, led to the two railroads that the building served, the Pennsylvania and the Long Island Rail Road. Its enormous main waiting room, inspired by the Roman Baths of Caracalla, approximated the scale of St. Peter's nave in Rome, expressed here in a steel framework clad in plaster that imitated the lower wall portions of travertine. It was the largest indoor space in New York City and, indeed, one of the largest public spaces in the world. Covering more than 7 acres (2.8 ha), it was, said the Baltimore Sun in April, 2007, “As grand a corporate statement in stone, glass and sculpture as one could imagine”.[16] In her 2007 book, Conquering Gotham: a Gilded Age Epic – The Construction of Penn Station and Its Tunnels, historian Jill Jonnes called the original edifice a “great Doric temple to transportation”.[17]

During the more than half-century timespan of the original station under owner Pennsylvania Railroad (1910–1963), scores of intercity passenger trains arrived and departed daily, serving distant places such as Chicago and St. Louis on “Pennsy” rails, and beyond on connecting railroads to Miami, Florida, and the west. In addition to the Long Island Rail Road, other lines using Pennsylvania Station during that era were the New Haven and the Lehigh Valley Railroads. For a few years during World War I and the early 1920s, arch rival Baltimore and Ohio Railroad passenger trains to Washington, Chicago, and St. Louis also used Pennsylvania Station, initially by order of the United States Railroad Administration (USRA), until the Pennsylvania Railroad terminated the B&O's access in 1926.[18] The station saw its heaviest usage during World War II, but by the late-1950s intercity rail passenger volumes declined dramatically with the coming of the Jet Age and the Interstate Highway System.

The Pennsylvania Railroad began looking to divest itself of the cost of operation of the underused structure, optioning the air rights of Penn Station in the 1950s. Plans for the new Penn Plaza and Madison Square Garden were announced in 1962. In exchange for the air-rights to Penn Station, the Pennsylvania Railroad would get a brand-new, air-conditioned, smaller station located completely below street level at no cost, and a 25% stake in the new Madison Square Garden Complex.

The demolition of the original structure — although considered by some to be justified as progressive at a time of declining rail passenger service — created international outrage.[16] As dismantling of the grand old structure began, The New York Times editorially lamented:

"Until the first blow fell, no one was convinced that Penn Station really would be demolished, or that New York would permit this monumental act of vandalism against one of the largest and finest landmarks of its age of Roman elegance.[19]"

Its destruction left a deep and lasting wound in the architectural consciousness of the city. A famous photograph of a smashed caryatid in the landfill of the New Jersey Meadowlands struck a guilty chord. Pennsylvania Station's demolition is considered to have been the catalyst for the enactment of the city's first architectural preservation statutes. The sculpture on the building, including the angel in the landfill, was created by Adolph Alexander Weinman. One of the sculpted clock surrounds, whose figures were modeled using model Audrey Munson, still survives as the Eagle Scout Memorial Fountain in Kansas City, Missouri. There is also a caryatid at the sculpture garden at the Brooklyn Museum, and 14 of the 22 original eagle ornaments still exist.[20] Ottawa's Union Station, built a year after Penn Station (in 1912), is another replica of the Baths of Caracalla. This train station's departures hall now provides a good idea of what the interior of Penn Station looked like (at half the scale). Chicago's Union Station is similar as well.

- Pennsylvania Station (1910-1963)

Demolition of station building; construction of Madison Square Garden

After a renovation covered some of the grand columns with plastic and blocked off the spacious central hallway with a new ticket office, Lewis Mumford wrote critically in The New Yorker in 1958 that “nothing further that could be done to the station could damage it”. History was to prove him wrong. Under the presidency of Pennsylvania Railroad's Stuart T. Saunders (who later headed ill-fated Penn Central Transportation), demolition of the above-ground components of this structure (the platforms are below street level) began in October 1963. Although the demolition did not disrupt the essential day-to-day operations, it made way for present-day Madison Square Garden, along with two office towers. A 1968 advertisement depicted architect Charles Luckman's model of the final plan for the Madison Square Garden Center complex, which would replace the original Pennsylvania Station.[21]

A point made in the defense of the demolition of the old Penn Station at the time was that the cost of maintaining the old structure had become prohibitive. The question of whether it made sense to preserve a building, intended to be a cost-effective and functional piece of the city's infrastructure, simply as a monument to the past was raised in defense of the plans to demolish it. As a New York Times editorial critical of the demolition noted at the time, a "civilization gets what it wants, is willing to pay for, and ultimately deserves."[19] Modern architects rushed to save the ornate building, although it was contrary to their own styles. They called the station a treasure and chanted "Don't Amputate – Renovate" at rallies.[22]

Only three eagles salvaged from the station are known to remain in New York City: two in front of the Penn Plaza / Madison Square Garden complex, and one at The Cooper Union, Weinman's alma mater. Cooper's eagle used to reside in the courtyard of the Albert Nerken School of Engineering at 51 Astor Place,[23] but was relocated in the summer of 2009, along with the engineering school, to a new academic building at 41 Cooper Square. This eagle is no longer viewable from the street, as it is located on the building's green roof.[24] Three are on Long Island: two at the United States Merchant Marine Academy in Kings Point and one at the Long Island Rail Road station in Hicksville, New York. Four reside on the Market Street Bridge in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, across from that city's 30th Street Station. One is positioned near the end zone at the football field of Hampden-Sydney College near Farmville, Virginia. Yet another is located on the grounds of the National Zoo in Washington, DC.

The furor over the demolition of such a well-known landmark, and its replacement by what continues to be widely deplored as a mediocre slab, are often cited as catalysts for the architectural preservation movement in the United States. New laws were passed to restrict such demolition. Within the decade, Grand Central Terminal was protected under the city's new landmarks preservation act, a protection upheld by the courts in 1978 after a challenge by Grand Central's owner, Penn Central.

The outcry over the loss of Penn Station prompted activists to question the “development scheme” mentality cultivated by New York's “master builder”, Robert Moses. Public protests and a rejection of his plan by the city government meant an end to Moses's plans for a Lower Manhattan Expressway.

In the longer run, the sense that something irreplaceable had been lost contributed to the erosion of confidence in Modernism itself and its sweeping forms of urban renewal. Interest in historic preservation was strengthened. Comparing the new and the old Penn Station, renowned Yale architectural historian Vincent Scully once wrote, “One entered the city like a god; one scuttles in now like a rat.” This feeling, shared by many New Yorkers, has led to movements for a new Penn Station that could somehow atone for the loss of an architectural treasure.[25]

Recent history and present day

The current Penn Station, on the site of the old one and using the same platforms, is arranged into "Amtrak", "NJ Transit" and "LIRR" concourses. Each one is maintained and styled differently by its respective operator. The NJ Transit concourse near Seventh Avenue is the newest and opened in 2002 out of existing retail and Amtrak backoffice space.[26][27] A new entrance to this concourse from West 31st Street opened in September 2009.[28] Previously, NJ Transit passengers could use only the Amtrak concourse to reach their trains. The main LIRR concourse runs below West 33rd Street between Seventh and Eighth Avenues. Significant renovations were made to this concourse over a three year period ending in 1994.[29] The LIRR's West End Concourse, west of Eighth Avenue, opened in 1986.[30] Parts of the Amtrak concourse (in particular, the shopping areas) maintain the original 1960s styling and have not been renovated since the new Penn Station was built; however, there have been renovations to other parts (the waiting rooms).

Tracks 1–12 are used only by Amtrak and NJ Transit trains, and the Amtrak and NJ Transit concourses both have gates to these tracks on the south side of the station. The LIRR has the exclusive use of Tracks 17–21 on the north side of the station and shares Tracks 13–16 with Amtrak and NJ Transit. Except for the shared tracks, a passenger can not reach the LIRR tracks directly from the Amtrak and NJ Transit concourses. Since Amtrak and NJ Transit share tracks, passengers from a NJ Transit train can wind up in the Amtrak concourse, and vice versa.

As of April 3, 2011 the public timetables show 212 weekday LIRR departures, 164 weekday NJ Transit departures, 51 Amtrak departures west to New Jersey and beyond (plus the triweekly Cardinal), 13 Amtrak departures north up the Hudson, and 21 Amtrak departures eastward.

In the 1990s, the current Pennsylvania Station was renovated by Amtrak, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, and New Jersey Transit, to improve the appearance of the waiting and concession areas, sharpen the station information systems (audio and visual) and remove much of the grime. Recalling the erstwhile grandeur of the bygone Penn Station, an old four-sided clock from the original depot was installed at the 34th Street Long Island Rail Road entrance. The walkway from that entrance's escalator also has a mural depicting elements of the old Penn Station's architecture.

After the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, passenger flow through the Penn Station Complex was curtailed. The taxiway under Madison Square Garden, which ran from 31st St north to 33rd St half way between 7th and 8th Avenues, was closed off with concrete Jersey barriers. A covered walkway from the taxiway was constructed to guide arriving passengers to a new taxi-stand on 31st Street.

Despite the improvements, Penn Station continues to be criticized as a low-ceilinged "catacomb" lacking charm, especially when compared to New York's much larger and ornate Grand Central Terminal. The New York Times, in a November 2007, editorial supporting development of an enlarged railroad terminal, said that "Amtrak's beleaguered customers…now scurry through underground rooms bereft of light or character".[31]

Future

Moynihan Station

Hope for a grander railroad station lies one block west. Across Eighth Avenue from Penn Station sits the James Farley Post Office. Under pressure from veteran U.S. Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, plans were publicized in 1999 to move entrances and concourses of Penn Station under this building, which fills an entire city block. When completed, the station inside the building would be named Moynihan Station, in honor of the late Senator.[32]

Initial design proposals were laid out by David Childs of Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill. In a protracted series of events typical of many large, complicated projects, plans to redevelop Penn Station have stretched further and further into the future. In July 2005, announcements were made that Childs' plan had been scrapped and a new one was unveiled. This second plan was similar to but much more modest than the original. It is the result of a collaboration between the architectural firms of James Carpenter and Hellmuth, Obata and Kassabaum (HOK). Later in 2005, Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill reacquired the project and released a third design, which is a compromise. As of June 2006, the design resembles the interior of BCE Place and does not require the demolition of part of the facade of the Farley Building.

Amtrak was to be the major tenant of the new building, leaving the old station for use by the NYC commuter rail passengers. Signs of construction appeared in November 2005, with plywood barriers installed on the sidewalks and orange nets covering main facade on 8th Avenue.[33]

Amtrak, however, subsequently decided not to move from its present location, leaving New Jersey Transit as the Moynihan Station's anchor tenant. NJ Transit has been negotiating a 99-year lease on the Farley Post Office.[34][35] In the meantime, Cablevision, owner of Madison Square Garden, considered relocation of the Garden to the west flank of the Farley Building. Such a project would lead to Vornado Realty Trust building an office complex on the current Garden site.[36]

Redevelopment of Penn Station thus continues to languish as various design concepts are debated and altered. A revised version proposed in 2007 would reportedly add 1,000,000 ft² (90,000 m²) of retail space to the new Moynihan train station and office complex, prompting the New York Times to complain that this latest plan "could easily shortchange the public's interests in favor of the private developers…The last thing New York needs is another dreadful Pennsylvania Station that only serves developers and Madison Square Garden."[31]

New York Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver has called for greater integration of the project with the larger Midtown renovation plan proposed by developers and Cablevision.[37][38]

A FAQ for New Jersey Transit's Trans-Hudson Express tunnel suggests that Pennsylvania Station, Moynihan Station, and a proposed rail station under 34th street will be considered to be separate entities.[39] The proximity and connection of those entities would make the Moynihan and 34th St. Stations de facto expansions of Penn Station. Daniel Patrick Moynihan's daughter, Maura Moynihan, has stated that she considers the Farley Building and current Madison Square Garden to be potential sites for two Moynihan Stations: a Moynihan-East and a Moynihan-West.[40]

On April 3, 2008, Madison Square Garden executives announced plans to renovate and modernize the current arena in time for the Knicks and Rangers 2011–12 seasons. This announcement came a week after they declared that they have abandoned plans to move the Garden to the Farley Post Office site. Hank J. Ratner, the vice chairman of Madison Square Garden said, “We're all for the development of Moynihan Station at the Farley building, as the project was originally conceived. We're not going to be moving."[41]

On February 16, 2010, $83.4 million from the federal government's TIGER program was awarded to the Moynihan Station project, which together with $169 million from other sources allows the first phase of construction to be fully funded. New construction plans include two new entrances from West of Eighth Avenue through the Farley Building, doubled length and width of the West End Concourse, thirteen new "vertical access points" (escalators, elevators and stairs) to the platforms, doubled width of the 33rd Street Connector between Penn and the West End Concourse, and other critical infrastructure improvements including platform ventilation and catenary work.[42] On July 30, 2010, the New York state government approved the plans; as a result, construction was expected to begin in October 2010, with completion of the first phase, including expansion of the west concourse, new entrances and improved ventilation scheduled for 2016.[43][44] On October 18, 2010, the ceremonial groundbreaking of the first phase of the project occurred, with numerous government officials in attendance.[44]

Gallery

- Pennsylvania Station in the 21st century

-

Long Island Rail Road (LIRR) underground concourse

-

Rush hour at the New Jersey Transit concourse

-

West Side Yard between Penn Station and the Hudson River

See also

- Atlantic Terminal

- Hoboken Terminal

- James Farley Post Office

- Pennsylvania Plaza

- Pennsylvania Station (Newark)

- Pennsylvania Tunnel and Terminal Railroad

- Transportation in New York City

References

- ^ Average weekday ridership

- ^ "Amtrak Fact Sheet, FY2010, State of New York" (PDF). Amtrak. November 2010. http://www.amtrak.com/pdf/factsheets/NEWYORK10.pdf. Retrieved 2011-01-06.

- ^ Average weekday, 2010 LIRR Annual Ridership and Marketing Report

- ^ Jackson, Kenneth T., ed. Encyclopedia of New York City, pp. 498 and 891.

- ^ Empire State Development. "About Moynihan Station." Accessed 2011-03-07.

- ^ Betts, Mary Beth (1995). "Pennsylvania Station". In Kenneth T. Jackson. The Encyclopedia of New York City. New Haven, CT & London & New York: Yale University Press & The New-York Historical Society. pp. 890–891.

- ^ Grynbaum, Micheal M. (October 18, 2010). "The Joys and Woes of Penn Station at 100". New York Times. http://cityroom.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/10/18/the-joys-and-woes-of-penn-station-at-100/?scp=2&sq=Penn%20Station%20busiest&st=cse. Retrieved 2011-02-16.

- ^ Amtrak National Facts, Bureau of Transportation Statistics, accessed November 8, 2009. In 2008, Penn Station saw 8,739,345 boardings.

- ^ Full list of US Airports Three Letter Codes – N, accessed August 1, 2006

- ^ Amtrak ClubAcela access eligibility and rules Retrieved 11 April 22:45 GMT

- ^ "Continental Ticket Offices." Continental Airlines. February 1, 2009.

- ^ a b c Donovan, Frank P. Jr. (1949). Railroads of America. Milwaukee: Kalmbach Publishing.

- ^ * Keys, C. M. (July 1910). "Cassatt and His Vision: Half a Billion Dollars Spent in Ten Years to Improve a Single Railroad – The End of a Forty-Year Effort to Cross the Hudson". The World's Work: A History of Our Time XX: 13187–13204. http://books.google.com/books?id=HsrkfU461xAC&pg=PA13187. Retrieved 2009-07-10.

- ^ Klein, Aaron E (January 1988). History of the New York Central. Greenwich, Connecticut: Bison Books. pp. 128. ISBN 0-517-460858. http://search.barnesandnoble.com/booksearch/isbninquiry.asp?box=0-517-460858&pos=-1&ISBN=0517460858.

- ^ a b Droege, John A. (1916). Passenger Terminals and Trains. New York: McGraw-Hill. http://books.google.com/books?id=Au5_AAAAMAAJ&dq=droege%20Passenger%20Terminals%20and%20Trains&pg=PA156&f=false.

- ^ a b Rasmussen, Frederick N. (April 21, 2007). "From the Gilded Age, a monument to transit". The Baltimore Sun.

- ^ Jonnes, Jill (2007). Conquering Gotham: a Gilded Age Epic – The Construction of Penn Station and Its Tunnels. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 9780670031580.

- ^ Harwood, Herbert H. Jr. (1990). Royal Blue Line. Sykesville, Md.: Greenberg Publishing. ISBN 0-89778-155-4.

- ^ a b "Farewell to Penn Station". The New York Times. October 30, 1963. http://www.nyc-architecture.com/GON/GON004.htm. Retrieved 2010-07-13. (The editorial goes on to say that “we will probably be judged not by the monuments we build but by those we have destroyed”).

- ^ Lee, Jennifer (September 11, 2009). "New Aerie for a Penn Station Eagle". New York Times City Room Blog. The New York Times. http://cityroom.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/09/11/new-aerie-for-a-penn-station-eagle/. Retrieved December 20, 2010.

- ^ nyc-architecture.com. "Madison Square Garden a New International Landmark." 1968 advertisement. New York Architecture Images: Madison Square Garden Center.

- ^ Gray, Christopher (May 20, 2001). "'The Destruction of Penn Station'; A 1960's Protest That Tried to Save a Piece of the Past". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2001/05/20/realestate/streetscapes-destruction-penn-station-1960-s-protest-that-tried-save-piece-past.html. Retrieved 2010-01-16.

- ^ von Meistersinger, Toby (September 4, 2007). "Keep an Eagle Eye Out for Penn Station Eagles". Gothamist. http://gothamist.com/2007/09/04/penn_station_eagles_in.php. Retrieved 2010-01-28.

- ^ "News Briefs: Cooper Union Eagle Takes Flight". At Cooper Union (Summer 2009): 4. http://cooper.edu/assets/pdfs/atCU/ACUs09briefs.pdf. Retrieved 2009-11-24.

- ^ “That it was torn down in 1963, mindlessly, has been with the city for a long while, how could we do that? We now have an opportunity to recreate the building.”Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Moynihan to Help Recreate NYC Pennsylvania Station, Reuters, Aug. 27, 2002.

- ^ "Commissioner Fox Unveils New 7th Avenue Concourse at Penn Station N.Y." (Press release). NJ Transit. September 18, 2002. http://www.njtransit.com/tm/tm_servlet.srv?hdnPageAction=PressReleaseTo&PRESS_RELEASE_ID=535. Retrieved 2010-01-16.

- ^ Lautenberg, Saundra and Baumann, Lynne M. (2000). "New Jersey Transit's East End Concourse."

- ^ Fahim, Kareem (November 6, 2006). "New Penn Station Entrance Is Planned by N.J. Transit". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2006/11/10/nyregion/10transit.html. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ^ Schaer, Sidney C. (October 23, 1994). "As LIRR Renovation Ends, Who's Laughing Now?". Newsday.

- ^ Washington, Ruby (December 12, 1986). "New Concourse Opens at Pennsylvania Station". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/1986/12/23/nyregion/new-concourse-opens-at-pennsylvania-station.html. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ^ a b "A Station Worthy of New York". The New York Times. November 2, 2007. http://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/02/opinion/02fri3.html. Retrieved 2007-11-26.

- ^ Bagli, Charles V. (July 18, 2005). "Team Chosen for Project to Develop Transit Hub". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2005/07/18/nyregion/18penn.html. Retrieved 2010-01-16.

- ^ The New Penn Station: When Will It Arrive?, accessed June 11, 2006

- ^ "Moynihan Station Development Corporation and NJ Transit Agree to Partner in Moynihan Station" (Press release). Empire State Development Corporation. November 21, 2005. http://www.empire.state.ny.us/press/press_display.asp?id=682. Retrieved 2010-01-16.

- ^ Magnet, Alec (November 22, 2005). "New Jersey Transit To Be Anchor Rail Tenant of Proposed Station". New York Sun. http://www.nysun.com/new-york/new-jersey-transit-to-be-anchor-rail-tenant/23355/. Retrieved 2010-01-16.

- ^ Corley, Colleen (February 15, 2006). "Online High Expectations for Madison Square Garden's Rumored $750M Move". Commercial Property News. http://www.cpexecutive.com/cpn/regions/article_display.jsp?vnu_content_id=1002033602. Retrieved 2010-01-16.[dead link]

- ^ Cuza, Bobby (October 11, 2006). "Sheldon Silver May Axe Moynihan Station Project". NY1. http://www.ny1.com/1-all-boroughs-news-content/top_stories/?SecID=1000&ArID=63381. Retrieved 2010-01-16.

- ^ Lombino, David (October 11, 2006). "Fate of Moynihan Rail Station Will Be Handed Over to Silver". The New York Sun. http://www.nysun.com/new-york/fate-of-moynihan-rail-station-will-be-handed-over/41333/. Retrieved 2010-01-16.

- ^ www.accesstotheregionscore.com

- ^ Moynihan, Maura (June 13, 2007). "Honor my father & build Moynihan Station". Daily News (New York). http://www.nydailynews.com/opinions/2007/06/13/2007-06-13_honor_my_father__build_moynihan_station.html. Retrieved 2010-01-16.

- ^ Bagli, Charles V. (April 4, 2009). "Garden Unfurls Its Plan for a Major Renovation". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/04/nyregion/04madison.html. Retrieved 2010-01-16.

- ^ Michaelson, Juliette (February 16, 2010). "Moynihan Station Awarded Federal Grant". Friends of Moynihan Station. http://www.moynihanstation.org/newsite/TIGER_statement_Friends_of_Moynihan_Station.pdf. Retrieved 2010-02-17.

- ^ "New York gets green light for Moynihan Station project's first phase". Progressive Railroading. July 30, 2010. http://www.progressiverailroading.com/news/article.asp?id=23911. Retrieved 2010-07-30.

- ^ a b "New York Penn Station expansion to finally see light of day". Trains. 2010-10-18. http://trn.trains.com/en/Railroad%20News/News%20Wire/2010/10/New%20York%20Penn%20Station%20expansion%20to%20finally%20see%20light%20of%20day.aspx. Retrieved 2010-10-20.

Bibliography

- Diehl, Lorraine B. (1985). The Late, Great Pennsylvania Station. Lexington, MA: Stephen Greene Press. ISBN 0-8289-0603-3.

- Johnston, Bob (January 2010). "Penn Station: How do they do it?". Trains 70 (1): 22–29. Includes track diagram.

External links

- Amtrak – Stations – Pennsylvania Station

- Official LIRR station information page for Penn Station

- Station timetable for Penn Station

- NJT rail station information page for Pennsylvania Station (New York City)

- DepartureVision real time train information for Pennsylvania Station (New York City)

- Diagram of New York Penn Station

- "New Penn Station" - Municipal Art Society of New York

- Photos and commentary documenting the demolition, by Norman McGrath

- Remnants of the old Penn Station

- American Society of Civil Engineers paper 1157: The New York tunnel extension of the Pennsylvania Railroad describes

- A short featuring 3D model of old New York Penn Station.

- Seventh Avenue and 32nd Street entrance from Google Maps Street View

- Eighth Avenue and 31st Street entrance from Google Maps Street View

- Eighth Avenue and 33rd Street entrance from Google Maps Street View

Major railroad stations of New York City and vicinity Active terminals Major transfer stations Historical terminals Categories:- Buildings and structures completed in 1910

- Pennsylvania Plaza

- Amtrak stations in New York

- Demolished railway stations in the United States

- Destroyed landmarks in the United States

- Former buildings and structures of New York City

- Beaux-Arts architecture in New York

- Railway stations opened in 1910

- Transportation in Manhattan

- Long Island Rail Road stations

- McKim, Mead, and White buildings

- New Jersey Transit stations

- Stations along Pennsylvania Railroad lines

- Stations along New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad lines

- Railroad terminals in New York City

- Union stations in the United States

- Transit centers in the United States

- Transit hubs serving New Jersey

- Eighth Avenue (Manhattan)

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.