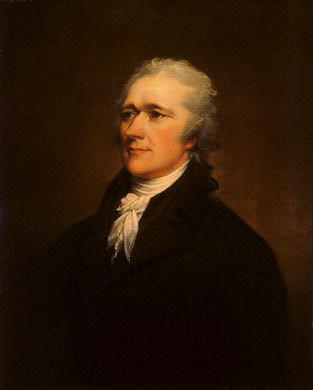

- Alexander Hamilton

Infobox US Cabinet official

name=Alexander Hamilton

order=1st

title=United States Secretary of the Treasury

term_start=September 11, 1789

term_end=January 31, 1795

president=George Washington

predecessor=(New office)

successor=Oliver Wolcott, Jr.

order3=Delegate fromNew York to the Constitutional Convention

term_start3=1787

term_end3=1787

order4=Delegate fromNew York County to theNew York State Legislature

term_start4=1787

term_end4=1788

order2=Delegate fromNew York to theCongress of the Confederation

term_start2=1788

term_end2=1789

order6=Delegate fromNew York to theCongress of the Confederation

term_start6=1782

term_end6=1783

order5=Delegate fromNew York to the Annapolis Convention

term_start5=1786

term_end5=1786

birth_date=January 11, 1755 or 1757

birth_place=Nevis ,Caribbean (nowSaint Kitts and Nevis )

death_date=July 12, 1804 (aged 49 or 47)

death_place=New York City ,New York

cause_of_death=Duel

party=Federalist

religion=Episcopalian at his death

spouse=Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton

profession=military officer ,lawyer ,financier ,political theorist

nickname =

allegiance=Province of New York (begin. 1775)State of New York (begin. 1776)United States of America (begin. 1777)

branch=New York Provincial Company of Artillery Continental Army United States Army

serviceyears=1775-1776 (Militia)

1776-1781

1798-1800

rank=Beginning:

)Highest:

)

commands=

unit=

battles=American Revolutionary War Battle of White Plains Battle of Trenton Battle of Princeton Battle of Monmouth Battle of Yorktown Quasi War

awards=

laterwork = President of the United States| Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757 – July 12, 1804) was the firstUnited States Secretary of the Treasury , a Founding Father,economist , andpolitical philosopher . He led calls for thePhiladelphia Convention , was one of America's firstConstitutional law yers, and cowrote the "Federalist Papers ", a primary source forConstitutional interpretation .Born on the

British West Indian island ofNevis , Hamilton was educated in theThirteen Colonies . During theAmerican Revolutionary War , he joined the American militia and was chosen artillery captain. Hamilton became senior [Chernow, p. 90.]aide-de-camp and confidant to GeneralGeorge Washington , and led three battalions at theSiege of Yorktown . He was elected to theContinental Congress , but resigned to practice law and to found theBank of New York . He served in theNew York Legislature , and was the only New Yorker who signed the Constitution. As Washington's Treasury Secretary, he influenced formative government policy widely. An admirer of British political systems, Hamilton emphasized strong central government andimplied powers , under which the newU.S. Congress funded thenational debt , assumed state debts, created a national bank, and established an import tariff andwhiskey tax .By 1792, a Hamilton coalition and a Jefferson–Madison coalition had arisen (the formative Federalist and

Democratic-Republican Parties), which differed strongly over Hamilton's domestic fiscal goals and his foreign policy of extensive trade and friendly relations with Britain. Exposed in an affair withMaria Reynolds , Hamilton resigned from the Treasury in 1795 to return to Constitutional law and advocacy of strong federalism. In 1798, theQuasi-War with France led Hamilton to argue for, organize, and become "de facto" commander of a national army.Hamilton's opposition to fellow Federalist

John Adams contributed to the success of Democratic-RepublicansThomas Jefferson andAaron Burr in the uniquely deadlockedelection of 1800 . With his party's defeat, Hamilton'snationalist andindustrializing ideas lost their former national prominence. In 1801, Hamilton founded the "New York Post " as the Federalistbroadsheet "New-York Evening Post". [Allan Nevins, "The Evening Post: Century of Journalism", Boni and Liveright, 1922, p. 17.] His intense rivalry with Vice President Burr eventually resulted in a duel, in which Hamilton was mortally wounded, dying the following day.Early years

By his own account, Hamilton was born in Charlestown, the capital of

Nevis in theBritish West Indies , out of wedlock to Rachel Faucett Lavien, of part FrenchHuguenot descent, and James A. Hamilton, fourth son of Scottishlaird Alexander Hamilton of Grange,Ayrshire . He was born on January 11 in either 1755 or 1757; most historians now say 1755, although disagreement remains. A young Hamilton claimed 1757 as his birth year when he first arrived in theThirteen Colonies ; but he is also recorded in probate papers, shortly after his mother's death, as being 13 years old, [From St. Croix records. Ramsing's 1930 Danish publication entered late among Hamilton literature.] indicating 1755. Explanations for this discrepancy include that he may have been trying to appear younger than his college classmates or to avoid standing out as older, that the probate document may be wrong, or he may have been passing as 13 to be more employable after his mother's death. [Chernow, Flexner, Mitchell's "Concise Life". McDonald, p. 366, n. 8, favors 1757, saying the probate clerk's alternate spelling of "Lavien" suggests unreliability; although he acknowledges most historians do not. ] He was often approximate about his age in later life.Hamilton's mother had been separated previously from Johann Michael Lavien of

St. Croix ; [Hamilton's spelling of "Lavien", which may be aSephardic version of "Levine"; Chernow, p. 10. The couple may have lived apart from one another under an order of legal separation, with Rachel as the guilty party, meaning remarriage was not permitted on St. Croix.] to escape an unhappy marriage, Rachel left her husband and first son forSt. Kitts in 1750, where she met James. [Chernow, p. 12.] They moved together to Rachel's birthplace of Nevis, where she had inherited property from her father.Chernow, p. 17.] Their two sons were James, Jr., and Alexander. Because Hamilton's parents were not legally married, theChurch of England denied him membership or education in the church school. Instead, he received "individual tutoring" and classes in a privateJewish school. [cite web|url=http://www.jewishpress.com/content.cfm?contentid=21464|author=Levine, Dr. Yitzchok|title=The Jews Of Nevis And Alexander Hamilton|publisher=Jewish Press|date=2007-05-02] Hamilton supplemented his education with a family library of thirty-four books, [Chernow, p. 24.] including Greek and Roman classics.A 1765 business assignment led Hamilton's father to move the family to

Christiansted , St. Croix; he then abandoned Rachel and the two sons. Rachel supported the family by keeping a small store in Christiansted. She contracted a severe fever and died on February 19, 1768, leaving Hamilton effectively orphaned. This may have had severe emotional consequences for him, even by the standards of an eighteenth-century childhood. [E.g., Flexner, "passim".] In probate court, Hamilton's half-brother obtained the few valuables Rachel had owned, including some household silver. Many items were auctioned off, but a friend purchased the family books and returned them to the studious young Hamilton. [Chernow, p. 25.] (Years later Hamilton received his half-brother's death notice and a small amount of money.) [Flexner, McDonald.]Hamilton then became a clerk at a local import-export firm, Beekman and Cruger, which traded with New England; he was left in charge of the firm for five months in 1771, while the owner was at sea. He and his older brother James were adopted briefly by a cousin, Peter Lytton, but when Lytton committed suicide, Hamilton was split from his brother. [Chernow, p. 26.] James apprenticed with a local carpenter, while Hamilton was adopted by Nevis merchant Thomas Stevens. Some evidence suggests Stevens may have been Hamilton's biological father: his son, Edward Stevens, became a close friend of Hamilton; the two boys looked much alike, were both fluent in French, and shared similar interests. [Chernow, pp. 27–30.]

Hamilton continued clerking, remained an avid reader, developed an interest in writing, and began to long for a life off his small island. A letter of Hamilton's was first published in the "Royal Danish-American Gazette", describing a hurricane that had devastated Christiansted on August 30, 1772. The impressed community began a collection for a subscription fund to educate the young Hamilton on the mainland of North America. He arrived, by way of Boston, at a

grammar school inElizabethtown, New Jersey , in the autumn of 1772.Education

In 1773, Hamilton attended a college-preparatory program with Francis Barber at Elizabethtown, New Jersey. There he came under the influence of a leading intellectual and revolutionary,

William Livingston . [Adair and Harvey.] Hamilton may have applied to the College of New Jersey (nowPrinceton University ) but been refused the opportunity for accelerated study; [The original source for this is a posthumous collection of anecdotes byHercules Mulligan , who said thatJohn Witherspoon refused Hamilton's demand to advance from class to class at his own speed; Mulligan's collection has been found unreliable by some biographers, including Mitchell and Flexner. Elkins and McKitrick comment that Witherspoon had just overseen similar programs forJames Madison , who collapsed from overwork, and Joseph Ross, who died young.] he decided to attend King's College inNew York City (nowColumbia University ). While studying there, Hamilton and several classmates were members of a campus literary group that foreran Columbia'sPhilolexian Society . [Chernow, p. 53.] [cite web|url=http://www.columbia.edu/cu/philo/content/about.htm|title=Philolexian History|accessdate=2008-06-30|publisher=Philolexian Society ]When Church of England clergyman

Samuel Seabury published a series of pamphlets promoting theTory cause the following year, Hamilton struck back with his first political writings, "A Full Vindication of the measures of Congress" and "The Farmer Refuted". He published two additional pieces attacking theQuebec Act [Morison and Commager, p. 160; Miller p. 19.] as well as fourteen anonymous installments of "The Monitor" for Holt's "New York Journal". Although Hamilton was a supporter of the Revolutionary cause at this prewar stage, he did not approve of mob reprisals against loyalists. One generally accepted account details how Hamilton saved his college president, Tory sympathizerMyles Cooper , from anangry mob , by speaking to the crowd long enough for Cooper to escape the danger. [McDonald, p. 14; Mitchell, I, p. 75; Chernow, p. 63. Flexner, p. 78, noting that Cooper's poem about the incident did not mention Hamilton, suggests that Hamilton was on a side of the building invisible to Cooper.]During the Revolutionary War

Early military career

In 1775, after the first engagement of American troops with the British in Boston, Hamilton joined a New York volunteer

militia company called the Hearts of Oak, which included other King's College students. He drilled with the company before classes, in the graveyard of nearbySt. Paul's Chapel . Hamilton studiedmilitary history and tactics on his own, and achieved the rank oflieutenant . Under fire from the HMS "Asia", he led a successful raid for British cannon in the Battery, the capture of which resulted in the Hearts of Oak becoming anartillery company thereafter. Through his connections with influential New York patriots likeAlexander McDougall andJohn Jay , he raised theNew York Provincial Company of Artillery of sixty men in 1776, and was elected captain. It took part in the campaign of 1776 around New York City, particularly at theBattle of White Plains ; at theBattle of Trenton , it was stationed at the high point of town, the meeting of the present Warren and Broad Streets, to keep the Hessians pinned in the Trenton Barracks. [Stryker, p. 158]Washington's staff

Hamilton was invited to become an aide to

Nathaniel Greene and other generals; however, he declined these invitations in the hopes of obtaining a place on Washington's staff. Hamilton did receive such an invitation, and joined as Washington's aide in March 1777 with the rank ofLieutenant Colonel . Hamilton served for four years, in effect, as Washington's Chief of Staff. [Chernow p 90] He handled the "letters to Congress, state governors, and the most powerful generals in the Continental Army". [Chernow p. 90] He drafted many of Washington's orders and letters at the latter's direction, and was eventually allowed to "issue orders from Washington over his own signature". [Chernow p. 90] Hamilton was involved in a wide variety of high-level duties, including intelligence,diplomacy , and negotiation withgeneral officers as Washington'semissary . [ Lodge 1: 15–20; Miller 23–26] The important duties with which he was entrusted attest to Washington's deep confidence in his abilities and character, then and afterward. At the points in their relationship where there was little personal attachment, there was still always a reciprocal confidence and respect.During the war Hamilton became close friends with several fellow officers, including

John Laurens and the Marquis de Lafayette. Jonathan Katz argues that Hamilton's letters to Laurens reveal at least a homosocial attachment and perhaps, in coded allusions to Greek history and mythology, a relationship modern readers would label homosexual. Ron Chernow implies this in discussing Laurens; Thomas Flexner portrays a similar homosocial relationship with Lafayette. These biographers may well be over-reading the literary conventions of the late eighteenth century, an age of sentiment. ["Gay American History" 1976; Flexner, "Young Hamilton", chiefly p. 316. For Chernow, and the criticism see Trees, Andrew S. "The Importance of Being Alexander Hamilton." (a review of Chernow) "Reviews in American History" 2005 33(1): 8–14 ]Marriage

In spring 1779, Hamilton asked his friend John Laurens to find him a wife in South Carolina: [Mitchell vol 1 p. 199] :

"She must be young—handsome (I lay most stress upon a good shape) Sensible (a little learning will do) —well bred... chaste and tender (I am an enthusiast in my notions of fidelity and fondness); of some good nature—a great deal of generosity (she must neither love money nor scolding, for I dislike equally a and an economist)—In politics, I am indifferent what side she may be of—I think I have arguments that will safely convert her to mine—As to religion a moderate stock will satisfy me—She must believe in God and hate a saint. But as to fortune, the larger stock of that the better."

Hamilton found his own bride on December 14, 1780 when he married Elizabeth Schuyler, daughter of General

Philip Schuyler , and thus joined one of the richest and most political families in the state of New York. The marriage took place atSchuyler Mansion inAlbany, New York .Hamilton grew extremely close to Eliza's sister, Angelica Church, who was married to John Barker Church, a

Member of Parliament in Great Britain. [ Chernow, p. 133] Some historians argue that the two may have had an affair, although, due to extensive editing of much Hamilton-Church correspondence by Hamilton's later descendants, it is impossible to know for sure. [ Chernow, p. 133–4]Command and the Battle of Yorktown

While on Washington's staff, Hamilton had long been seeking a command position in an active combat situation. As the war drew ever nearer to a close, he knew that opportunities for military glory were slipping away. In February 1781, Hamilton was mildly reprimanded by Washington, and used this as an excuse for resigning his staff position. Immediately following his resignation from Washington's staff, Hamilton began to ask Washington and others incessantly for a field command. This continued until early July of 1781, when Hamilton submitted a letter to Washington with his commission enclosed, "thus tacitly threatening to resign if he didn't get his desired command". [Chernow p. 159]

On July 31, 1781, Washington relented, and Hamilton was given command of a New York

light infantry battalion. In the planning for the assault on Yorktown, Hamilton was given command of threebattalion s which were to fight in conjunction with French troops in takingRedoubt s #9 and #10 of the British fortifications at Yorktown. Hamilton and his battalions fought bravely and took Redoubt #10 withbayonets , as planned. The French also fought bravely, took heavy casualties, and successfully took Redoubt #9. This action forced the British surrender at Yorktown of an entire army, effectively ending the British effort to reclaim the Thirteen Colonies. [Mitchell, p. 254–60; Morison and Commager, p. 160]Under the Confederation

Hamilton enters Congress

While on Washington's staff, Hamilton became frustrated with the decentralized nature of the wartime Continental Congress, particularly its dependence upon the states for financial support: it had no power to collect taxes, or to demand money from the states; this had caused serious problems in Army supplies and pay. Congress had given up printing unsupported paper money back in September 1779; it obtained what money it had from subsidies from the King of France, aid requested from the several states (which were often unable or unwilling to contribute), and loans from Europe against these uncertain revenues. [Kohn; Brant, p. 45; Rakove, p. 324.] After Yorktown, Hamilton resigned his commission. He was elected to the

Congress of the Confederation as a New York representative beginning on November 1782; [Syrett III, 117; he was elected in July 1782 for a one year term beginning the "first Monday in November next", arrived in Philadelphia between Nov. 18 and 25, and resigned July 1783.] he supported such Congressmen as superintendent of finance Robert Morris, his assistantGouverneur Morris (no relation),James Wilson , andJames Madison , who had already been trying to provide the Congress with an independent source of revenue it lacked under theArticles of Confederation .An amendment to the Articles had been proposed by

Thomas Burke , in February 1781, to give Congress the power to collect a 5% impost or duty on all imports, but this required ratification by all states; securing its passage as law proved impossible after it was rejected by Rhode Island in November 1782. Madison joined Hamilton in convincing Congress to send a delegation to persuade Rhode Island to change its mind. Their report recommending the delegation also argued that the federal government needed not just some level of financial autonomy, but also the ability to make laws that supersede those of the individual states. Hamilton transmitted a letter arguing that Congress already had the power to tax, since it had the power to fix the sums due from the several states; but Virginia's rescission of its own ratification ended Rhode Island negotiations. [Brant, p. 100; Chernow, p. 176.]Congress and the Army

While Hamilton was in Congress, discontented soldiers began to be a danger to the young United States. Most of the army was then posted at

Newburgh, New York . The army was paying for much of their own supplies, and they had not been paid in eight months. Furthermore, the Continental officers had been promised, in May 1778, afterValley Forge , a pension of half their pay when they were discharged. [Martin and Lender, p. 109, 160. At first for seven years, increased to life after Arnold's treason.] It was at this time that a group of officers organized under the leadership of GeneralHenry Knox sent a delegation to lobby Congress, led by Capt. Alexander MacDougall (see above). The officers had three demands: the Army's pay, their own pensions, andcommutation of those pensions into a lump-sum payment.Several Congressmen, including Hamilton and the Morrises, attempted to use this

Newburgh conspiracy as leverage to secure independent support for funding for the federal government in Congress and from the states. They encouraged MacDougall to continue his aggressive approach, threatening unknown consequences if their demands were not granted, and defeated proposals which would have resolved the crisis without establishing general federal taxation: that the states assume the debt to the army, or that an impost be established dedicated to the sole purpose of paying that debt.Kohn, Ellis 2004, pp. 141–4.] Late in January 1783, Hamilton suggested using the Army's claims to prevail upon the states for the proposed national funding system. [Kohn, p. 196, Congressional minutes of January 28, 1783.] In February, the Morrises and Hamilton contacted Knox to suggest he and the officers defy civil authority, at least by not disbanding if the army were not satisfied; Hamilton wrote Washington to suggest that he covertly "take direction" of the officers' efforts to secure redress, to secure continental funding but keep the army within the limits of moderation. [Quotation from Hamilton's letter of Feb. 13, 1783; Syrett, III, pp. 253–5. For interpretation, see Chernow, p. 177; cf. Martin and Lender pp. 189–90.] Washington wrote Hamilton back, declining to introduce the army; [Washington to Hamilton, 4th and March 12, 1783; Kohn, Martin and Lender pp. 189–90.] after the crisis was over, he warned of the dangers of using the army as leverage to gain support for the national funding plan. [Chernow, pp. 177–180, citing cite web|url=http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/etcbin/ot2www-washington?specfile=/texts/english/washington/fitzpatrick/search/gw.o2w&act=surround&offset=32820924&tag=Writings+of+Washington,+Vol.+26:+*To+ALEXANDER+HAMILTON&id=gw260334|author=Washington, George|title=To Alexander Hamilton|date=1783-04-04|accessdate=2008-05-20] On March 15, Washington defused the Newburgh situation by giving a speech to the officers. Congress ordered the Army officially disbanded in April 1783. In the same month, Congress passed a new measure for a twenty-five year impost, which Hamilton voted against, [Rakove, pp. 322, 325.] and which again required the consent of all the states; it also approved a commutation of the officers' pensions to five years of full pay. Rhode Island again opposed these provisions, and Hamilton's robust assertions of national prerogatives in his previous letter offended many.Vague|date=September 2008 [Brant, p. 108] The Continental Congress was never able to secure full ratification for back pay, pensions, or their own independent sources of funding.In June 1783, a different group of disgruntled soldiers from Lancaster, Pennsylvania sent Congress a petition demanding their back pay. When they began to march toward Philadelphia, Congress charged Hamilton and two others to intercept the mob. [Chernow, p. 180.] Hamilton requested militia from Pennsylvania's Supreme Executive Council, but was turned down. Hamilton instructed Assistant Secretary of War William Jackson to intercept the men. Jackson was unsuccessful. The mob arrived in Philadelphia, and proceeded to harangue Congress for their pay. The President of Congress, John Dickinson, feared the Pennsylvania state militia was unreliable, and refused their help. Hamilton argued that Congress ought to adjourn to Princeton, New Jersey. Congress agreed, and relocated there. [Chernow, p. 182.]

Frustrated with the weakness of the central government, Hamilton drafted a call to revise the Articles of Confederation while in Princeton. This resolution contained many features of the future U.S. Constitution, including a strong federal government with the ability to collect taxes and raise an army. It also included the separation of powers into the Executive, Legislative and Judicial branches. [Chernow, p. 183.]

Return to New York

Hamilton resigned from Congress, and in July 1783 was admitted to the New York Bar after several months of self-directed education. [Chernow, p. 160] He soon began a law practice in New York City. He specialized in defending Tories and British subjects, as in "

Rutgers v. Waddington ", in which he defeated a claim for damages done to a brewery by the Englishmen who held it during the military occupation of New York. He pleaded that the Mayor's Court should interpret state law to be consistent with the 1783 Treaty of Paris, which had ended the Revolutionary War. [Chernow, pp. 197–9, McDonald p. 64–9]In 1784, he founded the

Bank of New York , now the oldest ongoing banking organization in the United States. Hamilton was one of the men who restored King's College, which had been suspended since theBattle of Long Island in 1776 and severely damaged during the War, as Columbia College. His public career resumed when he attended the Annapolis Convention as a delegate in 1786. While there, he drafted its resolution for a Constitutional convention, and in doing so brought his longtime desire to have a more powerful, more financially independent federal government one step closer to reality.Constitution and the "Federalist Papers"

In 1787, Hamilton served as assemblyman from

New York County in theNew York State Legislature and was the first delegate chosen to the Constitutional Convention. In spite of the fact that Hamilton had been a leader in calling for a new Constitutional Convention, his direct influence at the Convention itself was quite limited. Governor George Clinton's faction in the New York legislature had chosen New York's other two delegates, John Lansing andRobert Yates , and both of them opposed Hamilton's goal of a strong national government. Thus, while the other two members of the New York delegation were present, they decided New York's vote; and when they left the convention in protest, Hamilton remained with no vote (two representatives were required for any state to cast a vote).Early in the Convention he made a speech proposing what many considered a very

monarchical government for the United States. Though regarded as one of his most eloquent speeches, it had little effect upon the deliberations of the convention. He proposed to have an elected President and electedSenators who would serve for life contingent upon "good behavior", [Chernow, p. 232.] and subject to removal for corruption or abuse. Hamilton's plan attempted to incorporate the "liberties of a republic" [Chernow, p. 232.] while "guarding against both anarchy and tyranny", [Chernow, p. 232.] yet his plan was probably the least trusting in the wisdom of the people. The deliberations of the convention were intended to be secret, so as to promote a free and vigorous flow of ideas during the Convention. However, some notes were kept, and due to Hamilton's argument for lifelong terms, and his proposal of measures that some contemporaries saw as too similar to previous monarchist forms of government, Hamilton acquired the reputation in some circles of a monarchist sympathizer.During the convention, Hamilton constructed a draft for the Constitution on the basis of the convention debates, but he never actually presented it. This draft had most of the features of the actual Constitution, including such details as the

three-fifths clause . In this draft, the Senate was to be elected in proportion to population, being two-fifths the size of the House, and the President and Senators were to be elected through complex multi-stage elections, in which chosenelector s would elect smaller bodies of electors; they would hold office for life, but were removable for misconduct. The President would have an absoluteveto . The Supreme Court was to have immediate jurisdiction over alllaw suits involving the United States, and State governors were to be appointed by the federal government. [Mitchell, p. 397 ff.]At the end of the Convention, Hamilton was still not content with the final form of the Constitution, but signed off on it anyway as a vast improvement over the Articles of Confederation, and urged his fellow delegates to do so also. [Irving Brant, "Fourth President", p. 195.] Since the other two members of the New York delegation, Lansing and Yates, had already withdrawn, Hamilton was the only New York signatory to the United States Constitution. He then took a highly active part in the successful campaign for the document's ratification in New York in 1788, which was a crucial step in its national ratification. Hamilton recruited John Jay and James Madison to write a defense of the proposed Constitution, now known as the "

Federalist Papers ", and made the largest contribution to that effort, writing 51 of 85 essays published (Madison wrote 29, Jay only five). Hamilton's essays and arguments were influential in New York state, and elsewhere, during the debates over ratification. The "Federalist Papers" are more often cited than any other primary source by jurists, lawyers, historians and political scientists as the major contemporary interpretation of the Constitution.. [Lupu, Ira C.; "The Most-Cited Federalist Papers." "Constitutional Commentary" (1998) pp. 403+; using Supreme Court citations, the five most cited wereFederalist No. 42 (Madison) (33 decisions),Federalist No. 78 (Hamilton) (30 decisions),Federalist No. 81 (Hamilton) (27 decisions),Federalist No. 51 (Madison) (26 decisions),Federalist No. 32 (Hamilton) (25 decisions).]In 1788, Hamilton served yet another term in what proved to be the last time the

Continental Congress met under theArticles of Confederation . He remained involved in the politics of New York: the ratification of the Constitution had been a success for two of the family cliques which constituted New York State politics, against a third, that led by George Clinton; the Legislature of 1789 had a majority of those two factions, one led by Hamilton's father-in-law, the other by the Livingston family. They had agreed to each select one of New York's first Senators:Phillip Schuyler was to be one, andJames Duane , whose wife was a Livingston, was to be the other. Hamilton, however, persuaded the Legislature to elect Schuyler and his friendRufus King , instead. The Livingstons responded by breaking the alliance and supporting the Clintons instead; this new coalition was to be the basis for the Democratic-Republican Party in New York. When Phillip Schuyler's term ended in 1791, they began by electing, in his place, the attorney-general of New York, oneAaron Burr . Hamilton blamed Burr for this result, and ill characterizations of Burr appear in his correspondence thereafter, although they did work together from time to time on various projects, including Hamilton's army of 1798 and theManhattan Water Company . [Lomask, pp. 139–40, 216–17, 220.]ecretary of the Treasury: 1789–1795

President George Washington appointed Hamilton as the first

Secretary of the Treasury on September 11, 1789. He left office on the last day of January 1795; much of the structure of the Government of the United States was worked out in those five years, beginning with the structure and function of the Cabinet itself.Forrest McDonald argues that Hamilton saw his office, like the BritishChancellor of the Exchequer , as that of a Prime Minister; Hamilton would oversee his colleagues under the elective reign of George Washington. Washington did request Hamilton's advice and assistance on matters outside the purview of theTreasury Department .Within one year, Hamilton submitted five reports:

*First Report on the Public Credit : Communicated to the House of Representatives, January 14, 1790.

*Operations of the Act Laying Duties on Imports : Communicated to the House of Representatives, April 23, 1790.

*Second Report on Public Credit : Report on a National Bank. Communicated to the House of Representatives, December 14, 1790.

*Report on the Establishment of a Mint : Communicated to the House of Representatives, January 28, 1791.

*Report on Manufactures : Communicated to the House of Representatives, December 5, 1791.Report on Public Credit

In the Report on Public Credit, the Secretary made a controversial proposal that would have the federal government assume state debts incurred during the Revolution. This would, in effect, give the federal government much more power by placing the country's most serious financial obligation in the hands of the federal, rather than the state governments.

The primary criticism of the plan was spearheaded by Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson and Representative

James Madison . Some states, like Jefferson's Virginia, had paid almost half of their debts, and felt that their taxpayers should not be assessed again to bail out the less provident. They further argued that the plan passed beyond the scope of the new Constitutional government.Madison objected to Hamilton's proposal to cut the rate of interest and postpone payments on federal debt, as not being payment in full; he also objected to the speculative profits being made. Much of the national debt had been bonds issued to Continental veterans, in place of wages which the Continental Congress did not have the money to pay; as these continued to go unpaid, many of these bonds had been pawned for a small fraction of their value. Madison proposed to pay in full, but to divide payment between the original recipient and the present possessor. Others, like

Samuel Livermore of New Hampshire, wished to curb speculation, and save taxation, by paying only part of the bond. The disagreements between Madison and Hamilton extended to other proposals Hamilton made to Congress, and drew in Jefferson when he returned from France. Hamilton's supporters became known as Federalists and Jefferson's as Republicans. As Madison put it: :"I deserted Colonel Hamilton, or rather Colonel H. deserted me; in a word, the divergence between us took place from his wishing to administration, or rather to administer the Government into what he thought it ought to be..." [Max Farrand, ed., The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787 (RFC), 4 vols. (New Haven, Conn., 1937), 3:533–34]Hamilton eventually secured passage of his assumption plan by striking a deal with Jefferson and Madison. According to the terms, Hamilton was to use his influence to place the permanent national capital on the

Potomac River , and Jefferson and Madison were to encourage their friends to back Hamilton's assumption plan. In the end, Hamilton's assumption, together with his proposals for funding the debt, overcame legislative opposition and narrowly passed the House on July 26, 1790. [cite book |title=Alexander Hamilton and the Growth of the New Nation |last=Miller |first=John |year=2003 |publisher=Transaction Publishers|location=New Brunswick, USA and London, UK|isbn=0765805510 |page=251]Founding the U.S. Mint

Hamilton helped found the

United States Mint ; the first national bank; a "System of Cutters", forming theRevenue Cutter Service , (now theUnited States Coast Guard ) and an elaborate system of duties, tariffs, and excises. The complete Hamiltonian program replaced the chaotic financial system of the confederation era, in five years, with a modern apparatus which gave the new government financial stability, and gave investors sufficient confidence to invest in government bonds.ources of revenue

One of the principal sources of revenue Hamilton prevailed upon Congress to approve was an

excise tax onwhiskey . Strong opposition to the whiskey tax by cottage producers in remote, rural regions erupted into theWhiskey Rebellion in 1794; inWestern Pennsylvania and westernVirginia , whiskey was commonly made (and used as a form of currency) by most of the community. In response to the rebellion, believing compliance with the laws was vital to the establishment of federal authority, he accompanied to the rebellion's site President Washington, General Henry "Light Horse Harry" Lee, and more federal troops than were ever assembled in one place during the War for Independence. This overwhelming display of force intimidated the leaders of the insurrection, ending the rebellion virtually without bloodshed. [Morison and Commager, I 309–11]Manufacturing and industry

Hamilton's next report was his "Report on Manufactures". Congress shelved the report without much debate, except for Madison's objection to Hamilton's formulation of the General Welfare clause, which Hamilton construed liberally as a legal basis for his extensive programs. It has been often quoted by

protectionist s since. [Morrison and Commager, I, p. 290]In 1791, while still Secretary of the Treasury, Hamilton worked in a private capacity to help found the

Society for the Establishment of Useful Manufactures , a private corporation that would use the power of theGreat Falls of the Passaic River to operate mills. Although the company did not succeed in its original purpose, it leased the land around the falls to other mill ventures and continued to operate for over a century and a half.Emergence of parties

During Hamilton's tenure as Treasury Secretary, political factions began to emerge. A Congressional caucus, led by James Madison and

William Giles , began as an opposition group to Hamilton's financial programs; Jefferson joined this group when he returned from France. Hamilton and his allies began to call themselves "Federalists". The opposition group, now referred to as theDemocratic-Republican Party , was then known by several names, including "Republicans", [cite web | title = James Madison to Thomas Jefferson, March 2, 1794 | url = http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=mjm&fileName=05/mjm05.db&recNum=591 | accessdate = 2006-10-14 "I see by a paper of last evening that even in New York a meeting of the people has taken place, at the instance of the Republican party, and that a committee is appointed for the like purpose." See also: Smith, p. 832.] "republicans", [ [http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?ammem/mtj:@field%28DOCID+@lit%28tj060237%29%29 Thomas Jefferson to President Washington, May 23, 1792] "The republican party, who wish to preserve the government in its present form, are fewer in number. They are fewer even when joined by the two, three, or half dozen anti-federalists,..."] "Jeffersonians", and "Democrats".The Federalists assembled a nationwide coalition in order to garner support for the Administration, including the expansive financial programs Hamilton had made Administration policy; the Democratic-Republicans built their own national coalition to oppose these Federalist programs. Both sides gained the support of local political factions; each side developed its own partisan newspapers.

Noah Webster ,John Fenno , and eventuallyWilliam Cobbett were prominent editors for the Federalists.Benjamin Franklin Bache andPhilip Freneau edited major publications for the Democratic-Republicans. Newspapers of both parties were characterized by frequent personal attacks and information of questionable veracity.In 1801, Hamilton established a daily newspaper the "New-York Evening Post" under editor

William Coleman . It is the oldest continually-published daily newspaper in the U.S., and is now known as the "New York Post ". [Michael & Edward Emery, "The Press and America", 7th edition, Simon & Schuster, 1992, p. 74]Revolutionary wars

When France and Britain went to war in January 1793, all four members of the Cabinet were consulted on what to do (they unanimously agreed to remain neutral); and both Hamilton and Jefferson were major architects in working out the specific provisions which maintained and enforced that neutrality. [Thomas, Charles Marion: "American neutrality in 1793; a study in cabinet government", Columbia, 1931. This is a survey of the process before Jefferson resigned at the end of 1793.]

During Hamilton's last year in office, policy toward Britain became a major point of contention between the two parties. Hamilton and the Federalists wished for more trade with Britain, which would provide more revenue from tariffs; the Democratic-Republicans preferred an embargo to compel Britain to respect the rights of the United States and give up the forts which they still held on American soil, contrary to the Treaty of Paris. [Jerald A. Combs. [http://www.anb.org/articles/02/02-00195.html John Jay] , "American National Biography Online", February 2000. Retrieved on May 14, 2008.]

In order to avoid war, Washington sent Chief Justice

John Jay , late in 1794, to negotiate with the British; Hamilton helped to draw up his instructions. The result wasJay's Treaty , which, as the State Department says, "addressed few U.S. interests, and ultimately granted Britain additional rights". [ [http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ho/time/nr/14318.htm John Jay’s Treaty, 1794–95] U.S. State Dept. website.] The treaty was extremely unpopular, and the Democratic-Republicans opposed it for its failure to redress previous grievances, and for its failure to address British violations of American neutrality during the war.Several European nations had formed a

League of Armed Neutrality against incursions on their neutral rights; the Cabinet was also consulted on whether the United States should join it, and decided not to, but kept that decision secret. Jay, in London, threatened to join the League if U.S. rights were not respected, but this was ignored because Hamilton had revealed this decision in private to George Hammond, the British Minister to the United States, without telling Jay—or anyone else; it was unknown until Hammond's dispatches were read in the 1920s. This "amazing revelation" may have had limited effect on the negotiations; Jay did threaten to join the League at one point, but the British had other reasons not to view the League as a serious threat. [Samuel Flagg Bemis, "Jay's Treaty" (quoted); Elkins and McKitrick p. 411 "f".]Retirement from federal service

Hamilton's conduct as Secretary was repeatedly investigated in Congress; some of the most serious charges emerged in the spring of 1794. In addition to the Reynolds affair, mentioned below, an incident from 1790 then came to light: Congress had appropriated money to pay the European creditors of the United States, and Hamilton had diverted part of the sum to domestic expenditure. Hamilton claimed that he had been authorized to act by Washington, but could provide no evidence. When Washington was consulted, he could not remember the transaction, but was certain that he would have made the condition that the change be consistent with legislation. Hamilton wrote an irate letter to Washington; he was very angry not to trusted unconditionally. [Flexner, "Washington", IV, 153–4'] Hamilton resigned as Secretary of the Treasury on December 1, 1794, immediately before Congress met again; his resignation was effective on January 31, 1795. [Chernow, p. 479, "ANB" Hamilton.]

Affair

In 1791, Hamilton became involved in an affair with

Maria Reynolds that badly damaged his reputation. Reynolds' husband, James,blackmailed Hamilton for money, threatening to inform Hamilton's wife. When James Reynolds was arrested for counterfeiting, he contacted several prominent members of the Democratic-Republican Party, most notablyJames Monroe andAaron Burr , touting that he could expose a top level official for corruption. When they interviewed Hamilton with their suspicions (presuming that James Reynolds could implicate Hamilton in an abuse of his position in Washington's Cabinet), Hamilton insisted he was innocent of any misconduct in public office and admitted to an affair with Maria Reynolds. Since this was not germane to Hamilton's conduct in office, Hamilton's interviewers did not publish about Reynolds. When rumors began spreading after his retirement, Hamilton published a confession of his affair, shocking his family and supporters by not merely confessing but also by narrating the affair in detail, thus injuring Hamilton's reputation for the rest of his life.At first Hamilton accused Monroe of making his affair public, and challenged him to a duel. Aaron Burr stepped in and persuaded Hamilton that Monroe was innocent of the accusation. His well-known vitriolic temper led Hamilton to challenge several others to duels in his career.

1796 presidential election

Hamilton's resignation as Secretary of the Treasury in 1795 did not remove him from public life. With the resumption of his law practice, he remained close to Washington as an adviser and friend. Hamilton influenced Washington in the composition of his Farewell Address; Washington and members of his Cabinet often consulted with him.

In the election of 1796, under the Constitution as it stood then, each of the presidential Electors had two votes, which they were to cast for different men. The one with most votes would be President, the second, Vice President. This system was not designed for parties, which had been thought disreputable and factious. The Federalists planned to deal with this by having all their Electors vote for

John Adams , the Vice President, and all but a few forThomas Pinckney ofSouth Carolina , then on his way home from a successful embassage to Spain. Jefferson chose Aaron Burr as his vice presidential running mate.Hamilton, however, disliked Adams and saw an opportunity. He urged all the Northern Electors to vote for Adams and Pinckney, lest Jefferson get in. He cooperated with

Edward Rutledge to have South Carolina's Electors vote for Jefferson and Pinckney. If all this worked, Pinckney would have more votes than Adams; Pinckney would be President, and Adams would remain Vice President. It did not work. The Federalists found out about it (even the French minister to the United States knew), and Northern Federalists voted for Adams but "not" for Pinckney, in sufficient numbers that Pinckney came in third and Jefferson became Vice President. [Elkins and McKitrick; "Age of Federalism".pp. 523–8, 859; Rutledge had his own plan, to have Pinckney win with "Jefferson" as Vice President.] Adams resented this, since he felt his service to the nation was much more extensive than Pinckney's. [Elkins and McKitrick, p. 515] Adams also resented Hamilton's influence with Washington and considered him overambitious and scandalous in his private life; Hamilton compared Adams unfavorably with Washington and thought him too emotionally unstable to be President.Quasi-War

During the

Quasi-War of 1798–1800, and with Washington's strong endorsement, Adams reluctantly appointed Hamilton amajor general of the army (essentially placing him in command since Washington could not leave Mt. Vernon). If full scale war broke out with France, Hamilton argued that the army should conquer the North American colonies of France's ally, Spain, bordering the United States.To fund this army, Hamilton had been writing incessantly to

Oliver Wolcott , his successor at the Treasury;William Loughton Smith , of the House Ways and Means Committee; and SenatorTheodore Sedgwick of Massachusetts. He directed them to pass a direct tax to fund the war. Smith was to resign in July of 1797, as Hamilton scolded him for slowness, and told Wolcott to tax houses instead of land. [ Newman, p. 72–3]The eventual program included a

Stamp Act , like that of the British before the Revolution, and an array of taxes on land, houses, and slaves, calculated at different rates in different states, and requiring difficult and intricate assessment of houses. This provoked resistance in south-eastern Pennsylania, led primarily by men who had marched with Washington against the Whiskey Rebellion, such asJohn Fries . [Newman, pp. 44, 76–8]Hamilton aided in all areas of the Army's development, and officially served as the Senior Officer of the United States Army as a Major General from December 14, 1799 to June 15, 1800. The army was to guard against invasion from France. Hamilton also suggested that its strategy should involve marching into the possessions of Spain, then allied with France, and potentially even taking Louisiana and Mexico. His correspondence further suggests that when he returned in military glory, he dreamed of setting up a properly energetic government, without any Jeffersonians. Adams, however, derailed all plans for war by opening negotiations with France. [Morison and Commager, p. 327] Adams had also held it right to retain Washington's cabinet, except for cause; he found, in 1800 (after Washington's death), that they were obeying Hamilton rather than himself, and fired several of them. ["ANB"

James McHenry ; he also firedTimothy Pickering .]1800 presidential election

In the 1800 election, Hamilton worked to defeat not only the rival Democratic-Republican candidates, but also his party's own nominee, John Adams. In New York, which Burr had won for Jefferson in May, Hamilton proposed a rerun of the election under different rules [The May 1800 election chose the New York Legislature, which would in turn choose Electors; Burr had won this by making it a referendum on the Presidency, and by persuading better qualified candidates to run, who declared their candidacy only after the Federalists had announced their ticket. Hamilton asked Jay and the lame-duck legislature to pass a law declaring a special Federal election, in which each district would choose an Elector. He also supplied a map, with as many Federal districts as possible.] with carefully drawn districts, each choosing an Elector, so that the Federalists would split the electoral vote of New York. John Jay, a Federalist, who had given up the Supreme Court to be Governor of New York, wrote on the back of the letter the words "Proposing a measure for party purposes which it would not become me to adopt", and declined to reply. [Monaghan, p. 419–421.]

John Adams was running this time with Pinckney's elder brother

Charles Cotesworth Pinckney . On the other hand, Hamilton touredNew England , again urging Northern Electors to hold firm for this Pinckney, in the renewed hope to make Pinckney President; and he again intrigued in South Carolina. This time, the important reaction was from the Jeffersonian Electors, all of whom voted both for Jefferson and Burr to ensure that no such deal would result in electing a Federalist. (Burr had received only one vote from Virginia in 1796.)In September, Hamilton wrote a pamphlet ("Letter from Alexander Hamilton, Concerning the Public Conduct and Character of John Adams, Esq. President of the United States") which was highly critical of Adams, although it closed with a tepid endorsement. He mailed this to two hundred leading Federalists; when a copy fell into Democratic-Republican hands, they printed it. This hurt Adams's 1800 reelection campaign and split the Federalist Party, virtually assuring the victory of the Democratic-Republican Party, led by Jefferson, in the election of 1800; it destroyed Hamilton's position among the Federalists. [Elkins and McKitrick, like other historians, speak of Hamilton's self-destructive tendencies in this connection.]

On the Federalist side, Governor

Arthur Fenner of Rhode Island denounced these "jockeying tricks" to make Pinckney President, and one Rhode Island Elector voted for Adams and Jay. Jefferson and Burr tied for first and second; and Pinckney came in fourth. [Elkins and McKitrick, p. 734–40]Jefferson had beaten Adams, but both he and his running mate, Aaron Burr, received 73 votes in the Electoral College. With Jefferson and Burr tied, the United States House of Representatives had to choose between the two men. (As a result of this election, the Twelfth Amendment was proposed and ratified, adopting the method under which presidential elections are held today.) Several Federalists who opposed Jefferson supported Burr, and for the first 35 ballots, Jefferson was denied a majority. Before the 36th ballot, Hamilton threw his weight behind Jefferson, supporting the arrangement reached by James A. Bayard of Delaware, in which five Federalist Representatives from Maryland and Vermont abstained from voting, allowing those states' delegations to go for Jefferson, ending the impasse and electing Jefferson

President rather than Burr. Even though Hamilton did not like Jefferson and disagreed with him on many issues, he was quoted as saying, "At least Jefferson was honest." Hamilton felt that Burr was dangerous. Burr then becameVice President of the United States . When it became clear that he would not be asked to run again with Jefferson, Burr sought the New York governorship in 1804 with Federalist support, against the JeffersonianMorgan Lewis , but was defeated by forces including Hamilton. ["ANB" "Aaron Burr"]Duel with Aaron Burr and death

Soon after the gubernatorial election in New York—in which Morgan Lewis, greatly assisted by Hamilton, defeated

Aaron Burr —the "Albany Register" published Charles D. Cooper's letter, citing Hamilton's opposition to Burr and alleging that Hamilton expressed "a still more despicable opinion" of the Vice President at an upstate New York dinner party. [Kennedy, "Burr, Hamilton, and Jefferson", p. 72.] Burr, sensing an attack on his honor, and surely still stung by the political defeat, demanded an apology. Hamilton refused on the grounds that he could not recall the instance.Following an exchange of three testy letters, and despite the attempts of friends to avert a confrontation, a duel was nevertheless scheduled for July 11, 1804, along the west bank of the

Hudson River on a rocky ledge inWeehawken, New Jersey , a common dueling site at which Hamilton's eldest son, Philip, had been killed three years earlier.At dawn, the duel began, and Vice President Aaron Burr shot Hamilton. Hamilton's shot broke a tree branch directly above Burr's head. A letter that he wrote the night before the duel states, "I have resolved, if our interview [duel] is conducted in the usual manner, and it pleases God to give me the opportunity, to reserve and throw away my first fire, and I have thoughts even of reserving my second fire", thus asserting an intention to miss Burr. The circumstances of the duel, and Hamilton's actual intentions, are still disputed. Neither of the seconds, Pendleton or Van Ness, could determine who fired first. Soon after, they measured and triangulated the shooting, but could not determine from which angle Hamilton fired. Burr's shot, however, hit Hamilton in the lower abdomen above the right hip. The bullet ricocheted off Hamilton's second or third false rib, fracturing it and caused considerable damage to his internal organs, particularly his

liver and diaphragm before becoming lodged in his first or second lumbar vertebra. Chernow considers the circumstances to have indicated Burr to have fired second, and taken deliberate aim. [Chernow, Ron "Alexander Hamilton" ]If a duelist decided not to aim at his opponent there was a well-known procedure, available to everyone involved, for doing so. According to Freeman, Hamilton apparently did not follow this procedure; if he had, Burr might have followed suit, and Hamilton's death may have been avoided. It was a matter of honor among gentlemen to follow these rules. Because of the high incidence of

septicemia and death resulting from torso wounds, a high percentage of duels employed this procedure of throwing away fire.cite journal|author=Freeman, Joanne B|url=http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0043-5597%28199604%293%3A53%3A2%3C289%3ADAPRTB%3E2.0.CO%3B2-S|title=Dueling as Politics: Reinterpreting the Burr-Hamilton Duel|journal=The William and Mary Quarterly, Third Series|volume=53|issue=2|month=April 1996|pages=289–318|format=subscription|publisher=Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture] Years later, when told that Hamilton may have misled him at the duel, the ever-laconic Burr replied, "Contemptible, if true." [Joseph Wheelan, "Jefferson's Vendetta: The Pursuit of Aaron Burr and the Judiciary", New York, Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2005, ISBN 0786714379, p. 90]Hamilton was ferried back to New York. After final visits from his family and friends and considerable suffering, Hamilton died on the following afternoon, July 12, 1804.

Gouverneur Morris , a political ally of Hamilton's, gave the eulogy at his funeral and secretly established a fund to support his widow and children. Hamilton was buried in theTrinity Churchyard Cemetery inManhattan .Legacy

From the start, Hamilton set a precedent as a Cabinet member by formulating federal programs, writing them in the form of reports, pushing for their approval by appearing in person to argue them on the floor of the United States Congress, and then implementing them. Hamilton and the other Cabinet members were vital to Washington, as there was no president before him (under the Constitution) to set precedents for him to follow in national situations such as seditions and foreign affairs.

Another of Hamilton's legacies was his pro-federal interpretation of the U.S. Constitution. Though the Constitution was drafted in a way that was somewhat ambiguous as to the balance of power between national and state governments, Hamilton consistently took the side of greater federal power at the expense of states. As Secretary of the Treasury, he established—against the intense opposition of Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson—the country's first national bank. Hamilton justified the creation of this bank, and other increased federal powers, with Congress's constitutional powers to issue currency, to regulate interstate commerce, and anything else that would be "necessary and proper". Jefferson, on the other hand, took a stricter view of the Constitution: parsing the text carefully, he found no specific authorization for a national bank. This controversy was eventually settled by the

Supreme Court of the United States in "McCulloch v. Maryland ", which in essence adopted Hamilton's view, granting the federal government broad freedom to select the best means to execute its constitutionally enumerated powers, specifically the doctrine ofimplied powers .Hamilton's policies as Secretary of the Treasury have had an immeasurable effect on the United States Government and still continue to influence it. In 1962 during the

Cuban Missile Crisis , theU.S. Navy was still using inter-ship communication protocols written by Hamilton for the original U.S. Coast Guard. His constitutional interpretation, specifically of thenecessary-and-proper clause , set precedents for federal authority that are still used by the courts and are considered an authority on constitutional interpretation. The prominent French diplomat Charles Maurice de Talleyrand, who spent 1794 in the United States, wrote "I consider Napoleon, Fox, and Hamilton the three greatest men of our epoch, and if I were forced to decide between the three, I would give without hesitation the first place to Hamilton", adding that Hamilton had intuited the problems of European conservatives. Talleyrand, who helped demolish theFirst French Republic , would have preferred to have a coalition of European monarchies curtail the solitary republicanism of the United States, which would permit the peaceful recreation of the French colonial empire of Louis XIV; he found himself and Hamilton in general agreement. [Adams, 238–243, Talleyrand's words, as Adams quotes them, are from "Études sur la République": "Je considère Napoleon, Fox, et Hamilton comme les trois plus grands hommes de notre époque, et si je devais me prononcer entre les trois, je donnerais sans hesiter la première place à Hamilton. Il avait deviné l'Europe." .]Opinions of Hamilton have run the gamut: both John Adams and Thomas Jefferson viewed him as unprincipled and dangerously aristocratic. He was sufficiently admired by the time of the

American Civil War that his portrait began to appear on US currency, and now appears on the $10 bill; after the Civil War, a time of high tariffs, he was highly praised. [Brant, "Fourth President", p. 201 says "apotheosis"; but he may, in context, be writing of historians, such asJames Ford Rhodes .]Herbert Croly ,Henry Cabot Lodge , andTheodore Roosevelt directed attention to him at the end of the nineteenth century in the interest of an active federal government, whether or not supported by tariffs. Several nineteenth and twentieth century Republicans entered politics by writing laudatory biographies of Hamilton. [Flexner, Introduction; for example,Arthur H. Vandenburg wrote "The Greatest American" in 1922, when he was still a newspaper editor, likewiseHenry Cabot Lodge 's "Alexander Hamilton" was written when he was a junior professor; for the effect on his career of his "advocacy of his party's views", see "American National Biography", [http://www.anb.org/articles/06/06-00671.html?a=1&n=Vandenberg&ia=-at&ib=-bib&d=10&ss=0&q=2 Arthur H. Vandenburg] . ]Hamilton's portrait began to appear during the

American Civil War on the $2, $5, $10, and $50 notes. His face continues to appear on the front of the ten dollar bill. Hamilton also appears on the $500 Series EE Savings Bond. The source of the face on the $10 bill isJohn Trumbull 's 1805 portrait of Hamilton, in the portrait collection ofNew York City Hall . ["The New York Times". December 6, 2006. "In New York, Taking Years Off the Old, Famous Faces Adorning City Hall." [http://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/06/nyregion/06portraits.html?ref=nyregion] ] On the south side of the Treasury Building inWashington, D.C. is a statue of Hamilton.Hamilton's upper

Manhattan home is preserved asHamilton Grange National Memorial , with a statue of Hamilton at the entrance. The historic structure, already removed from its original location many years ago, is being moved again—from its current position, sandwiched between two masonry buildings, to a spot in a nearby park on land that was once part of the Hamilton estate. [ [http://www.nps.gov/hagr/ Hamilton Grange National Memorial (U.S. National Park Service) ] ] It is expected to re-open to the public in 2009.Multiple towns throughout the United States have been named after Hamilton.

Family

Hamilton's widow, Elizabeth (known as Eliza or Betsy), survived him for fifty years, until 1854; Hamilton had referred to her as "best of wives and best of women". An extremely religious woman, Eliza spent much of her life working to help widows and orphans. After Hamilton's death, Eliza sold the country house, the Grange, that she and Hamilton had built together from 1800 to 1802. She co-founded New York's first private orphanage, the New York Orphan Asylum Society. Despite the Reynolds affair, Alexander and Eliza were very close, and as a widow she always strove to guard his reputation and enhance his standing in American history.

Hamilton and Elizabeth had eight children, including two named Phillip. The elder Philip, Hamilton's first child (born January 22, 1782), was killed in 1801 in a duel with George I. Eacker, whom he had publicly insulted in a Manhattan theater. The second Philip, Hamilton's last child, was born on June 2, 1802, after the first Philip was killed. Their other children were Angelica, born September 25, 1784; Alexander, born May 16, 1796; James Alexander (April 14, 1788 – September 1878); [ [http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?res=9E05E2DE123CE03BBC4E51DFBF668383669FDE James Alexander Hamilton obituary, "The New York Times". September 26, 1878] .] John Church, born August 22, 1792; William Stephen, born August 4, 1797; and Eliza, born November 26, 1799.Fact|date=March 2008

On slavery

Modern scholarly views on Hamilton's attitude to slavery have been described as viewing Hamilton as anything from a "steadfast abolitionist" to a "hypocrite"; one middle view is that he was deeply ambivalent. [Quotes describing the historiography from Weston, who disagrees with both, finding Hamilton ambivalent.]

Hamilton's first polemic against King George's ministers contains a paragraph which speaks of the evils which "slavery" to the British would bring upon the Americans. One biographer sees this as an attack on actual slavery; [McDonald] such hostility was quite common in 1776. [McManus; "Many national leaders including Washington, Franklin, Jefferson, Madison, Hamilton, John Adams, John Jay, Gouverneur Morris, and Rufus King, saw slavery as an immense problem, a curse, a blight, or a national disease." David Brion Davis, "Inhuman Bondage" p.156; Morison and Commager quote Patrick Henry's regrets at being unable to give up the comforts of slave-owning. ]

During the Revolutionary War, there was a series of proposals to arm slaves, free them, and compensate their masters. [The first of these projects was made in August 1776, by

Jonathan Dickinson Sargeant , see "Arming slaves" pp. 192–3, 206; Rhode Island had formed the First Rhode Island regiment in 1777. which fought theBattle of Rhode Island ; and there were other black units. Sidney Kaplan: The Black Presence in the Era of the American Revolution", p. 64 ff] Freeing any enlisted slaves had also become customary by then both for the British, who did not compensate their American masters, and for the Continental Army; some states were to require it before the end of the war. [McManus, pp. 153–58. ] In 1779, Hamilton's friendJohn Laurens suggested such a unit be formed under his command, to relieve besiegedCharleston, South Carolina ; Hamilton wrote a letter to the Continental Congress to create up to four battalions of slaves for combat duty, and free them. Congress recommended that South Carolina (and Georgia) acquire up to three thousand slaves, if they saw fit; they did not, even though the South Carolina governor and Congressional delegation had supported the plan in Philadelphia. [ Mitchell 1:175–77, 550 n.92; citing the Journals of the Continental Congress for [http://rs6.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?ammem/hlaw:@field(DOCID+@lit(jc01380)) March 29, 1779] ; Wallace p 455. Congress offered to compensate their masters after the war. ]Hamilton argued that blacks' natural faculties were as good as those of free whites, and he forestalled objections by citing

Frederick the Great and others as praising obedience and lack of cultivation in soldiers; he also argued that if the Americans did not do this, the British would (as they had elsewhere). One of his biographers has cited this incident as evidence that Hamilton and Laurens saw the Revolution and the struggle against slavery as inseparable. [letter to Jay of [http://press-pubs.uchicago.edu/founders/documents/v1ch15s24.html March 14, 1779] ; Chernow p.121. McManus, p. 154–7 ] Hamilton later attacked his political opponents as demanding freedom for themselves and refusing to allow it to blacks. [ McDonald, p. 34; Flexner, p. 257–8, ]In January 1785, he attended the second meeting of the

New York Manumission Society (NYMS).John Jay was president and Hamilton was secretary; he later became president. [McManus, p. 168.] He was also a member of the committee of the society which put a bill through the New York Legislature banning the "export" of slaves from New York; [Chernow, p. 216] three months later, Hamilton returned a fugitive slave toHenry Laurens of South Carolina. [Littlefield, p. 126, citing Syrett: 3:605–8. The mention in Wills, p. 209, that Hamilton arranged, a decade later, as Secretary of the Treasury, to recapture one of Washington's slaves is a chronological error; it was his successor, Oliver Wolcott, of Connecticut.]Hamilton never supported forced emigration for freed slaves; it has been argued from this that he would be comfortable with a multiracial society, and this distinguished him from his contemporaries. [Horton, p. 22] In international affairs, he supported

Toussaint L'Ouverture 's black government inHaiti after the revolt that overthrew French control, as he had supported aid to the slaveowners in 1791—both measures hurt France. [ Horton; Kennedy p. 97–98; Littlefield. Wills, p. 35, 40 ] He may have owned household slaves himself (the evidence for this is indirect; one biographer interprets it as referring to paid employees), [McDonald] and he did buy and sell them on behalf of others. He supported agag rule to keep divisive discussions of slavery out of Congress, and he supported the compromise by which the United States could not abolish the slave trade for twenty years. [Flexner, p. 39] When the Quakers of New York petitioned the First Congress (under the Constitution) for the abolition of the slave trade, and Benjamin Franklin and the Pennsylvania Abolition Society petitioned for the abolition of slavery, the NYMS did not act. [McDonald, p. 177]On economics

Alexander Hamilton is sometimes considered the "

patron saint " of the American School of economic philosophy that, according to one historian, dominated economic policy after 1861. [Lind, Michael. "Hamilton's Republic" (1997) pages xiv–xv, 229–30.] He firmly supported government intervention in favor of business, after the manner ofJean-Baptiste Colbert , as early as the fall of 1781. [Chernow, 170; citing "Continentalist" V, Syrett: 3:77; published April 1782, but written Fall 1781.]Hamilton opposed the British ideas of

free trade which he believed skewed benefits to colonial/imperial powers, in favor of U.S.protectionism which he believed would help develop the fledgling nation's emerging economy.Henry C. Carey was inspired by his writings. Some sayWho|date=September 2008 he influenced the ideas and work of GermanFriedrich List .Hamilton's religion

In his early life, he was an orthodox and conventional, though not deeply pious, Presbyterian. From 1777 to 1792, he appears to have been completely indifferent, and made jokes about God at the Constitutional Convention. During the French Revolution, he had an "opportunistic religiosity", using Christianity for political ends and insisting that Christianity and Jefferson's democracy were incompatible. After his misfortunes of 1801, he asserted the truth of the Christian revelation. He proposed a Christian Constitutional Society in 1802, to take hold of "some strong feeling of the mind" to elect "fit" men" to office; but Hamilton wrote also of "Christian welfare societies" for the poor. He was not a member of any denomination, but led his family in the Episcopal service the Sunday before the duel. After he was shot, Hamilton requested communion first from

Benjamin Moore , the Episcopal Bishop of New York, who initially declined to administer the Sacrament chiefly because he did not wish to sanction the practice of dueling. Hamilton then requested communion from Presbyterian pastorJohn Mason , who declined on the grounds that Presbyterians did not reserve the Sacrament. After Hamilton spoke of his belief in God's mercy, and of his desire to renounce dueling, Bishop Moore reversed his decision, and administered communion to Hamilton. [This entire paragraph, including the quote on religiosity, is from Adair and Harvey: " [http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0043-5597%28195504%293%3A12%3A2%3C308%3AWAHACS%3E2.0.CO%3B2-4 Christian Statesman?] " "passim". Hamilton's early faith is a deduction: Livingstone and Knox would have chosen to sponsor only an orthodox young man. Quotes on the Christian Constitutional Society are from Hamilton's letter to James A. Bayard of April 1802, as quoted by Adair and Harvey; they see this as a great change from the military preparations and Sedition Act of 1798. For Bishop Moore, see also Chernow, p. 707; McDonald, p. 3 on Hamilton's secular ambition, although he adds that Hamilton's faith "had not entirely departed" him before the crisis of 1801. (p. 356). ]Memorial at colleges

Alexander Hamilton served as one of the first trustees of the

Hamilton-Oneida Academy when the school opened in 1793. When the academy received a college charter in 1812 the school was formally renamedHamilton College . There is a prominent statue of Alexander Hamilton in front of the school's chapel (commonly referred to as the "Al-Ham" statue) and theBurke Library has an extensive collection of Hamilton's personal documents.Columbia College, Hamilton's alma mater, whose students formed his militia artillery company and fired some of the first shots against the British, has official memorials to Hamilton. The college's main classroom building for the humanities is Hamilton Hall, and a large statue of Hamilton stands in front of it. The university press has published his complete works in a multivolume

letterpress edition.The main administration building of the

Coast Guard Academy is named Hamilton Hall to commemorate Hamilton's creation of theUnited States Revenue Cutter Service , one of the entities that was combined to form theUnited States Coast Guard .References

:"The long tradition of Hamilton biography has, almost without exception, been laudatory in the extreme. Facts have been exaggerated, moved around, omitted, misunderstood and imaginatively created. The effect has been to produce a spotless champion...Those little satisfied with this reading of American history have struck back by depicting Hamilton as a devil devoted to undermining all that was most characteristic and noble in American life." James Thomas Flexner, "The Young Hamilton", pp. 3-4.

econdary sources

*

Henry Adams , "History of the United States of America under the Administrations of Thomas Jefferson", Library of America 1986, ISBN 0521324831

*Stanley Elkins and Eric McKitrick: "Age of Federalism" (New York, Oxford University Press, 1993). [http://www.questia.com/library/book/the-age-of-federalism-by-stanley-elkins-eric-mckitrick.jsp online edition]

*Samuel Eliot Morison andHenry Steele Commager : "Growth of the American Republic" (New York, Oxford University Press, 1969; other eds as cited).Biographies

*Brookhiser, Richard. "Alexander Hamilton, American". Free Press, (1999) (ISBN 0-684-83919-9).

*Chernow, Ron. "Alexander Hamilton". Penguin Books, (2004) (ISBN 1-59420-009-2). full length detailed biography

*Ellis, Joseph J. "" (2002), won Pulitzer Prize.

*Ellis, Joseph J. "His Excellency: George Washington". (2004).

*Flexner, James Thomas. "The Young Hamilton: A Biography". Fordham University Press, (1997) (ISBN 0-8232-1790-6).

*Fleming, Thomas. "Duel: Alexander Hamilton, Aaron Burr, and the Future of America". (2000) (ISBN 0-465-01737-1).

*McDonald, Forrest. "Alexander Hamilton: A Biography"(1982) (ISBN 0-393-30048-X), biography focused on intellectual history esp on AH's republicanism.

*Miller, John C. "Alexander Hamilton: Portrait in Paradox" (1959), full-length scholarly biography; [http://www.questia.com/library/book/alexander-hamilton-portrait-in-paradox-by-john-c-miller.jsp online edition]

*Mitchell, Broadus. "Alexander Hamilton" (2 vols, 1957–62), the most detailed scholarly biography; also published in abridged edition

*Randall, Willard Sterne. Alexander Hamilton: A Life. HarperCollins, (2003) (ISBN 0-06-019549-5). Popular.

*Don Winslow Alexander Hamilton: In Worlds Unknown (Script and Film New York Historical Society)pecialized studies

*Douglass Adair and Marvin Harvey: " [http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0043-5597%28195504%293%3A12%3A2%3C308%3AWAHACS%3E2.0.CO%3B2-4 Was Alexander Hamilton a Christian Statesman?] " "The William and Mary Quarterly", 3rd Ser., Vol. 12, No. 2, Alexander Hamilton: 1755–1804. (Apr., 1955), pp. 308–329.

JSTOR URL.

*"Arming slaves: from classical times to the modern age", Christopher Leslie Brown and Philip D. Morgan, eds. esp. 180–208 on the American Revolution, by Morgan and A. J. O'Shaubhnessy.

* Douglas Ambrose and Robert W. T. Martin, eds. "The Many Faces of Alexander Hamilton: The Life & Legacy of America's Most Elusive Founding Father " (2006).

*Brant, Irving: "The Fourth President: a Life of James Madison". Bobbs-Merill, 1970. A one-volume recasting of Brant's six-volume life.

*Burns, Eric. "Infamous Scribblers: The Founding Fathers and the Rowdy Beginnings of American Journalism." (2007).

* Chan, Michael D. "Alexander Hamilton on Slavery." "Review of Politics" 66 (Spring 2004): 207–31.

* Fatovic, Clement. "Constitutionalism and Presidential Prerogative: Jeffersonian and Hamiltonian Perspectives." "American Journal of Political Science" 2004 48(3): 429–444. Issn: 0092-5853 Fulltext in Swetswise, Ingenta, Jstor, Ebsco .

* Flaumenhaft; Harvey. "The Effective Republic: Administration and Constitution in the Thought of Alexander Hamilton" Duke University Press, 1992.

* Flexner, James Thomas. "George Washington." Little Brown, 1965–72. Four volumes, with various subtitles, cited as "Flexner, "Washington". Vol. IV ISBN 0316286028.

* Levine, Dr. Yitzchok. [http://www.jewishpress.com/content.cfm?contentid=21464&sContentid=1 "The Jews Of Nevis And Alexander Hamilton."] "Glimpses Into American Jewish History", The Jewish Press. May 2, 2007.

* Harper, John Lamberton. "American Machiavelli: Alexander Hamilton and the Origins of U.S. Foreign Policy." (2004).

* Horton, James Oliver. "Alexander Hamilton: Slavery and Race in a Revolutionary Generation" "New-York Journal of American History" 2004 65(3): 16–24. ISSN 1551-5486 [http://66.102.7.104/search?q=cache:88cftz6zXJYJ:www.alexanderhamiltonexhibition.org/about/Horton%2520-%2520Hamiltsvery_Race.pdf+james+horton+%22alexander+hamilton%22+slavery&hl=en&gl=us&ct=clnk&cd=1 online version] .

* Katz, Jonathan. "Gay American History: Lesbians and Gay Men in the U.S.A." Thomas Y. Crowell Company. 1976. ISBN 978-0690011647.

* Kennedy, Roger G. ; "Burr, Hamilton, and Jefferson: A Study in Character" Oxford University Press (2000).

*Knott, Stephen F. "Alexander Hamilton and the Persistence of Myth" University Press of Kansas, (2002) ISBN 0-7006-1157-6.

*Richard H. Kohn, " [http://www.jstor.org/stable/1918650 The Inside History of the Newburgh Conspiracy: America and the Coup d'Etat] "; "The William and Mary Quarterly, Third Series", Vol. 27, No. 2 (Apr., 1970), pp. 188–220.JSTOR link. A review of the evidence on Newburgh, source for most more recent coverage. Despite the title, Kohn is doubtful that a "coup d'état" was ever seriously attempted.

*Harold Larsen: " [http://www.jstor.org/stable/1925345.pdf Alexander Hamilton: The Fact and Fiction of His Early Years] " The William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd Ser., Vol. 9, No. 2. (Apr., 1952), pp. 139–151.JSTOR link.

* Littlefield, Daniel C. "John Jay, the Revolutionary Generation, and Slavery." "New York History" 2000 81(1): 91–132. ISSN 0146-437X.

*Milton Lomask , "Aaron Burr, the Years from Princeton to Vice President, 1756-1805". Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1979. ISBN 0374100160 First volume of two, but this contains Hamilton's lifetime.

* Martin, Robert W. T. "Reforming Republicanism: Alexander Hamilton's Theory of Republican Citizenship and Press Liberty." "Journal of the Early Republic" 2005 25(1): 21–46. Issn: 0275-1275 Fulltext online in Project Muse and Ebsco.

*McManus, Edgar J. "History of Negro Slavery in New York". Syracuse University Press, 1966.

*Mitchell, Broadus: "The man who 'discovered' Alexander Hamilton". "Proceedings of the New Jersey Historical Society" 1951. 69:88–115.

*Stryker, William S [cudder] .: "The Battles of Trenton and Princeton"; Houghton Mifflin, 1898.