- Military history of the United States

-

History of the United States

This article is part of a seriesTimeline Pre-Colonial period Colonial period 1776–1789 1789–1849 1849–1865 1865–1918 1918–1945 1945–1964 1964–1980 1980–1991 1991–present Topic Civil Rights (1896–1954) Civil Rights (1955–1968) Civil War Cultural history Demographic history Diplomatic history Economic history History of the South Military history Technological and industrial history Territorial evolution Women's history

United States Portal

The military history of the United States spans a period of over two centuries. During the course of those years, the United States evolved from a new nation fighting the British Empire for independence without a professional military (1775–1783), through a monumental American Civil War (1861–65) to the world's sole remaining superpower of the late 20th century and early 21st century.[1]

Overview

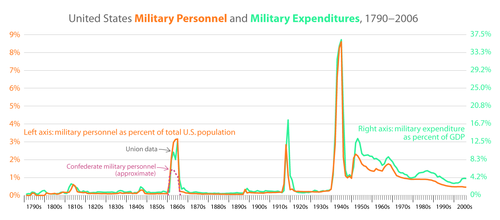

U.S. military personnel and expenditures, 1790–2006. Personnel is shown in orange (left axis); expenditures are in teal (right axis). The two axes are scaled to visually align for World War II, thus showing the difference between the cost per soldier before and after President Dwight D. Eisenhower's "New Look" policy of the early 1950s.[citation needed]

U.S. military personnel and expenditures, 1790–2006. Personnel is shown in orange (left axis); expenditures are in teal (right axis). The two axes are scaled to visually align for World War II, thus showing the difference between the cost per soldier before and after President Dwight D. Eisenhower's "New Look" policy of the early 1950s.[citation needed]

The Continental Congress in 1775 created the Continental Army and named General George Washington its commander. This newly formed army, along with state militia forces, and the French army and navy, defeated the British in 1783. The new Constitution in 1788 made the president the commander in chief, with authority for the Congress to levy taxes, and make the rules.[2]

As of 2011, the U.S. military consists of an Army, Navy, Air Force and Marine Corps under the command of the United States Department of Defense. There also is the United States Coast Guard, which is controlled by the Department of Homeland Security.

The President of the United States is the commander in chief of each branch of the armed forces. In addition, each state has a national guard commanded by the state's governor and coordinated by the National Guard Bureau. The President of the United States has the authority during national emergencies to assume control of individual state National Guard units.[3]

Timeline

Colonial wars (1620–1774)

The beginning of the United States military lies in civilian frontiersmen, armed for hunting and basic survival in the wilderness. These were organized into local militias for small military operations, mostly against Native American tribes but also to resist possible raids by the small military forces of neighboring European colonies. They relied on the British regular army and navy for any serious military operation.[4]

In major operations outside the locality involved, the militia was not employed as a fighting force. Instead the colony asked for (and paid) volunteers, many of whom were also militia members.[5]

In the early years of the British colonization of North America, military action in the thirteen colonies that would become the United States were the result of conflicts with Native Americans, such as in the Pequot War of 1637, King Philip's War in 1675, the Yamasee War in 1715 and Dummer's War in 1722.

Beginning in 1689, the colonies became involved in a series of wars between Great Britain and France for control of North America, the most important of which were Queen Anne's War, in which the British conquered French colony Acadia, and the final French and Indian War (1754–1763) when Britain was victorious over all the French colonies in North America. This final war was to give thousands of colonists, including Virginia colonel George Washington, military experience which they put to use during the American Revolution.[6]

War of Independence (1775–1783)

Detail from Washington and his Generals at Yorktown (c. 1781) by Charles Willson Peale. Lafayette (far left) is at Washington's right, the Comte de Rochambeau to his immediate left.

Detail from Washington and his Generals at Yorktown (c. 1781) by Charles Willson Peale. Lafayette (far left) is at Washington's right, the Comte de Rochambeau to his immediate left.

Ongoing political tensions between Great Britain and the thirteen colonies reached a crisis in 1774 when the British placed the province of Massachusetts under martial law after the Patriots protested illegal taxes. While shooting began at Lexington and Concord in 1775, the Continental Congress appointed George Washington as commander-in-chief of the newly created Continental Army, which was augmented throughout the war by colonial militia. General Washington was not the greatest battlefield tactician, but his overall strategy proved to be sound: keep the army intact, wear down British resolve, and avoid decisive battles except to exploit enemy mistakes.[7]

Washington's surprise crossing of the Delaware River in Dec. 1776 was a major comeback after the loss of New York City; his army defeated the British in two battles and recaptured New Jersey.

Washington's surprise crossing of the Delaware River in Dec. 1776 was a major comeback after the loss of New York City; his army defeated the British in two battles and recaptured New Jersey.

The British, for their part, lacked both a unified command and a clear strategy for winning. With the use of the Royal Navy, the British were able to capture coastal cities, but control of the countryside eluded them. A British invasion from Canada in 1777 ended with the disastrous surrender of a British army at Saratoga. With the coming in 1777 of General von Steuben, the training and discipline along Prussian lines began, and the Continental Army became a modern force. France and Spain then entered the war against Great Britain, ending its naval advantage and creating a world war.

A shift in focus to the southern American states resulted in a string of victories for the British, but guerrilla warfare and the tenacity of General Nathanael Greene's army prevented the British from making strategic headway. The main British army was surrounded by Washington's American and French forces at Yorktown in 1781, as the French fleet blocked a rescue by the Royal Navy. The American victory forced the British to sue for peace.

General George Washington (1732–1799) proved an excellent organizer and administrator, who worked successfully with Congress and the state governors, selecting and mentoring his senior officers, supporting and training his troops, and maintaining an idealistic Republican Army. His biggest challenge was logistics, since neither Congress nor the states had the funding to provide adequately for the equipment, munitions, clothing, paychecks, or even the food supply of the soldiers. As a battlefield tactician Washington was often outmaneuvered by his British counterparts. As a strategist, however, he had a better idea of how to win the war than they did. The British sent four invasion armies. Washington's strategy forced the first army out of Boston in 1776, and was responsible for the surrender of the second and third armies at Saratoga (1777) and Yorktown (1781). He limited the British control to New York and a few places while keeping Patriot control of the great majority of the population. The Loyalists, whom the British counted upon too heavily, comprised about 20% of the population but never were well organized. As the war ended, Washington watched proudly as the final British army quietly sailed out of New York City in November 1783, taking the Loyalist leadership with them. Washington astonished the world when instead of seizing power for himself, he retired quietly to his farm in Virginia.[8]

Since many Americans of the revolutionary generation had strong distrust of permanent (or "standing") armies, the Continental Army was quickly disbanded after the Revolution. General Washington, who throughout the war deferred to elected officials, averted a potential crisis and resigned as commander-in-chief to Congress after the war, establishing a tradition of civil control of the U.S. military.[9]

Early national period (1783–1812)

Following the American Revolution, the United States faced potential military conflict on the high seas as well as on the western frontier. The United States was a minor military power during this time, having only a modest army and navy. A traditional distrust of standing armies, combined with faith in the abilities of local militia, precluded the development of well-trained units and a professional officer corps. Jeffersonian leaders preferred a small army and navy, fearing that a large military establishment would involve the United States in excessive foreign wars, and potentially allow a domestic tyrant to seize power.[10]

In the Treaty of Paris after the Revolution, the British had ceded the lands between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River to the United States, without consulting the Shawnee, Cherokee, Choctaw and other smaller tribes who lived there. Because many of the tribes had fought as allies of the British, the United States compelled tribal leaders to sign away lands in postwar treaties, and began dividing up these lands for settlement. This provoked a war in the Northwest Territory in which the U.S. forces performed poorly; the Battle of the Wabash in 1791 was the most severe defeat ever suffered by the United States at the hands of American Indians. President Washington dispatched a newly trained army to the region, which decisively defeated the Indian confederacy at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794.[11]

When revolutionary France declared war on Great Britain in 1793, the United States sought to remain neutral, but the Jay Treaty, which was favorable to Great Britain, angered the French government, which viewed it as a violation of the 1778 Treaty of Alliance. French privateers began to seize U.S. vessels, which led to an undeclared "Quasi-War" between the two nations. Fought at sea from 1798 to 1800, the United States won a string of victories in the Caribbean. George Washington was called out of retirement to head a "provisional army" in case of invasion by France, but President John Adams managed to negotiate a truce, in which France agreed to terminate the prior alliance and cease its attacks.[12]

Barbary wars

The Berbers along the Barbary Coast (modern day Libya) sent pirates to capture merchant ships and hold the crews for ransom. The U.S. paid protection money until 1801, when President Thomas Jefferson refused to pay and sent in the Navy to challenge the Barbary States, the First Barbary War followed. After the U.S.S. Philadelphia was captured in 1803, Lieutenant Stephen Decatur led a raid which successfully burned the captured ship, preventing Tripoli from using or selling it. In 1805, after William Eaton captured the city of Derna, Tripoli agreed to a peace treaty. The other Barbary states continued to raid U.S. shipping, until the Second Barbary War in 1815 ended the practice.[13]

"We have met the enemy and they are ours." Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry's victory on Lake Erie in 1813 was an important turning point in the War of 1812. (Painting by William H. Powell, 1865)

"We have met the enemy and they are ours." Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry's victory on Lake Erie in 1813 was an important turning point in the War of 1812. (Painting by William H. Powell, 1865)

War of 1812

By far the largest military action in which the United States engaged during this era was the War of 1812. When the United Kingdom and France went to war again in 1803 with renewed vigor, the United States sought to remain neutral while pursuing overseas trade. This proved difficult, and the United States finally declared war on the United Kingdom in 1812, the first time the U.S. had officially declared war. Not hopeful of defeating the Royal Navy, the U.S. attacked the British Empire by invading British Canada, hoping to use captured territory as a bargaining chip. The invasion of Canada was a debacle, though concurrent wars with Native Americans on the western front (Tecumseh's War and the Creek War) were more successful. After defeating Napoleon in 1814, Britain sent large veteran armies to invade New York, raid Washington and capture the key control of the Mississippi River at New Orleans. The New York invasion was a fiasco after the much larger British army retreated to Canada. The raiders succeeded in burning of Washington on 25 August 1814, but were repulsed in their Chesapeake Bay Campaign at the Battle of Baltimore and the British commander killed. The major invasion in Louisiana was stooped by a one-sided military battle that killed the top three British generals and thousands of soldiers. The winner General Andrew Jackson became president as Americans basked in a victory over a much more powerful nation. The peace treaty proved successful, and the U.S. and Canada never again went to war. The losers were the Indians, who never gained the independent territory in the Midwest promised by Britain.[14]

War with Mexico (1846–48)

Main article: Mexican-American WarWith the rapid expansion of the farming population, Democrats looked to the west for new lands, an idea which became known as "Manifest Destiny". In the Texas Revolution (1835–36), the settlers declared independence and defeated the Mexican army, but Mexico was determined to reconquer the lost province sooner or later, and threatened war with the U.S. if it annexed Texas. The U.S., much larger and more powerful, did annex Texas in 1845 and war broke out in 1846 over boundary issues.[15][16]

In the Mexican-American War 1846–48, the U.S. Army under Generals Zachary Taylor and Winfield Scott and others, invaded and after a series of victorious battles (and no major defeats) seized New Mexico and California, and also blockaded the coast, invaded northern Mexico, and invaded central Mexico, capturing the national capital. The peace terms involved American purchase of the area from California to New Mexico for $10 million.[17]

American Civil War (1861–1865)

Dead soldiers lie where they fell at Antietam, the bloodiest day in American history. Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation after this battle.

Dead soldiers lie where they fell at Antietam, the bloodiest day in American history. Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation after this battle.

Sectional tensions had long existed between the states located north of the Mason-Dixon Line and those south of it, primarily centered on the "peculiar institution" of slavery and the ability of states to overrule the decisions of the national government. During the 1840s and 1850s, conflicts between the two sides became progressively more violent. After the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860 (who southerners thought would work to end slavery) states in the South seceded from the United States, beginning with South Carolina in late 1860. On April 12, 1861, forces of the South (known as the Confederate States of America or simply the Confederacy) opened fire on Fort Sumter, whose garrison was loyal to the Union.[18]

The American Civil War caught both sides unprepared. The Confederacy hoped to win by getting Britain and France to intervene, or else by wearing down the North's willingness to fight. The U.S. sought a quick victory focused on capturing the Confederate capital at Richmond, Virginia. The Confederates under Robert E. Lee tenaciously defended their capital until the very end. The war spilled across the continent, and even to the high seas. Most of the material and human resources of the South were used up, while the North prospered.

The American Civil War is sometimes called the "first modern war" due to the mobilization (and destruction) of the civilian base. It also is characterized by many technical innovations involving railroads, telegraphs, rifles, trench warfare, and ironclad warships with turret guns.[19]

Post-Civil War era (1865–1917)

Indian Wars (1865–1870)

Main article: Indian WarsAfter the Civil War, population expansion, railroad construction, and the disappearance of the buffalo herds, heightened military tensions on the Great Plains. Several tribes, especially the Sioux and Comanche, fiercely resisted confinement to reservations. The main role of the Army was to keep indigenous peoples on reservations as the United States carried out its plans for economic expansion. William Tecumseh Sherman and Philip Sheridan were in charge. A great victory for the Plains Nations was the Battle of the Little Big Horn in 1876, when Col. George Armstrong Custer and his regiment were all killed by a force consisting of many nations. [20]

Spanish-American War (1898)

Main article: Spanish-American WarThe Spanish-American War was a short decisive war marked by quick, overwhelming American victories at sea and on land against Spain. The Navy was well prepared and won laurels, even as politicians tried (and failed) to have it redeployed to defend East Coast cities against potential threats from the feeble Spanish fleet.[21] The Army performed well in combat in Cuba. However, it was too oriented to small posts in the West and not as well prepared for an overseas conflict.[22] It relied on volunteers and state militia units, which faced logistical, training and food problems in the staging areas in Florida.[23] The United States freed Cuba (after an occupation by the U.S. Army). By the peace treaty Spain ceded to the United States its colonies of Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines.[24] The Navy set up coaling stations there and in Hawaii (which voluntarily joined the U.S. in 1898). The U.S. Navy now had a major forward presence across the Pacific and (with the lease of Guantánamo Bay Naval Base in Cuba) a major base in the Caribbean guarding the approaches to the Gulf Coast and the Panama Canal.[25]

Philippine-American War (1899–1902)

The Philippine-American War (1899–1902), was an armed conflict between a group of Filipino revolutionaries and the American forces following the ceding of the Philippines to the United States after the defeat of Spanish forces in the Battle of Manila. The Army sent in 100,000 soldiers (mostly from the National Guard) under General Elwell Otis. Defeated in the field and losing its capital in March 1899, the poorly armed and poorly led rebels broke into armed bands. The insurgency collapsed in March 1901 when the leader Emilio Aguinaldo was captured by General Frederick Funston and his Macabebe allies. Casualties included 1037 Americans killed in action and 3340 who died from disease; 20,000 rebels were killed.[26]

Modernization

The Navy was modernized in the 1880s, and by the 1890s had adopted the naval power strategy of Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan--as indeed did every major navy. The old sailing ships were replaced by modern steel battleships, bringing them in line with the navies of Britain and Germany. In 1907, most of the Navy's battleships, with several support vessels, dubbed the Great White Fleet, were showcased in a 14-month circumnavigation of the world. Ordered by President Theodore Roosevelt, it was a mission designed to demonstrate the Navy's capability to extend to the global theater.[27]

Secretary of War Elihu Root (1899–1904) led the modernization of the Army. His goal of a uniformed chief of staff as general manager and a European-type general staff for planning was stymied by General Nelson A. Miles but did succeed in enlarging West Point and establishing the U.S. Army War College as well as the General Staff. Root changed the procedures for promotions and organized schools for the special branches of the service. He also devised the principle of rotating officers from staff to line. Root was concerned about the Army's role in governing the new territories acquired in 1898 and worked out the procedures for turning Cuba over to the Cubans, and wrote the charter of government for the Philippines.[28]

Rear Admiral Bradley A. Fiske was at the vanguard of new technology in naval guns and gunnery, thanks to his innovations in fire control 1890–1910. He immediately grasped the potential for air power, and called for the development of a torpedo plane. Fiske, as aide for operations in 1913–15 to Assistant Secretary Franklin D. Roosevelt, proposed a radical reorganization of the Navy to make it a war-fighting instrument. Fiske wanted to centralize authority in a chief of naval operations and an expert staff that would develop new strategies, oversee the construction of a larger fleet, coordinate war planning including force structure, mobilization plans, and industrial base, and insure that the US Navy possessed the best possible war machines. Eventually, the Navy adopted his reforms and by 1915 started to reorganize for possible involvement in the World War then underway.[29]

Banana Wars (1898–1935)

The Banana Wars is a term used to describe US intervention in Latin America from the end of the Spanish American War in 1898 until 1935. These wars include involvement in Cuba, Mexico, Panama with the Panama Canal Zone, Haiti (1915–1935), Dominican Republic (1916–1924) and Nicaragua (1912–1925) & (1926–1933). The U.S. Marine Corps began to specialize in long-term military occupation of these countries.

Most notable of these conflicts was when U.S. forces occupied the Mexican city of Veracruz for over six months in 1914, in response to the April 9, 1914 "Tampico Affair", which involved the brief arrest of U.S. sailors by soldiers of the regime of Mexican President Victoriano Huerta. The incident came in the midst of poor diplomatic relations with the United States, related to the ongoing Mexican Revolution.

Moro Rebellion (1899–1913)

The Moro Rebellion was an armed insurgency between Muslim Filipino tribes in the southern Philippines between 1899 to 1913. Pacification was never complete as sporadic anti-government insurgency continues into the 21st century, with American advisors helping the Philippine government forces.[30]

World War I (1917–1918)

Main articles: Border War (1910–1918), American entry into World War I, and American Expeditionary ForcesThe United States originally wished to remain neutral when World War I broke out in August 1914. However, it insisted on its right as a neutral party to immunity from German submarine attack. The ships carried food and raw materials to Britain. In 1917 the Germans resumed submarine attacks, knowing that it would lead to American entry. However the U.S. had deliberately kept its army small and mobilization took a year. Meanwhile the U.S. sent more supplies and money to Britain and France, and started the first peacetime draft.[31] Economic mobilization was much slower than expected, so the decision was made to send divisions to Europe without their equipment, relying instead on British and French supplies.[32]

By summer 1918, a million American soldiers, or "doughboys" as they were often called, of the American Expeditionary Force were in Europe under the command of John J. Pershing, with 25,000 more arriving every week. The failure of Germany's spring offensive meant it had exhausted its manpower reserves and were unable to launch attacks or even defend its lines. Meanwhile, the German home front revolted and a new German government signed a conditional surrender, the Armistice, ending the war on November 11, 1918.[33]

Russian Revolution

The so-called Polar Bear Expedition was the involvement of U.S. troops, during the tail end of World War I and the Russian Revolution, in fighting the Bolsheviks in Arkhangelsk, Russia in 1918 and 1919.

The U.S. sponsored a major world conference to limit the naval armaments of world powers, including the U.S., Britain, Japan, and France, plus smaller nations.[34] Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes made the key proposal of each country to reduce its number of warships by a formula that was accepted. The conference enabled the great powers to reduce their navies and avoid conflict in the Pacific. The treaties remained in effect for ten years, but were not renewed as tensions escalated.[35]

1930s: Neutrality Acts

After the costly U.S. involvement in World War I, isolationism grew within the nation. Congress refused membership in the League of Nations, and in response to the growing turmoil in Europe and Asia, the gradually more restrictive Neutrality Acts were passed, which were intended to prevent the U.S. from supporting either side in a war. President Franklin D. Roosevelt sought to support Britain, however, and in 1940 signed the Lend-Lease Act, which permitted an expansion of the "cash and carry" arms trade to develop with Britain, which controlled the Atlantic sea lanes.

Roosevelt favored the Navy (he was in effective charge in World War I), and used relief programs such as the PWA to support Navy yards and build warships. For example in 1933 he authorized $238 million in PWA funds for thirty-two new ships. The Army Air Corps received only $11 million, which barely covered replacements and allowed no expansion.[36]

World War II (1939–1945)

See also: Military history of the Philippines during World War II, Air warfare of World War II#United States: The U.S. Air Force, and Special relationshipDuring the interwar period the United States again reduced its military, but mobilized to its largest levels in history during World War II. The global conflict started on 1 September 1939 and raged until 2 September 1945, involving most of the peoples of the world. It was the most extensive and costly war in history as well as the history of the United States (excepting personnel).

US involvement in World War II was initially limited to providing war material and financial support to Britain, the Soviet Union, and the Republic of China. The US entered officially on 8 December 1941 following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii the previous day. This attack was followed by attacks on US, Dutch and British possessions across the Pacific. On 11 December, the remaining Axis powers, Germany and Italy, declared war on the US, drawing the US firmly into the war and removing all doubts about the global nature of the conflict.

The loss of 8 battleships and 2000 sailors and airmen at Pearl Harbor forced the US to rely on its remaining aircraft carriers, which won a major victory over Japan at Midway just 6 months into the war, and its growing submarine fleet. The Navy and Marine Corps followed this up with an island hopping campaign across the central and South Pacific in 1943–45, reaching the outskirts of Japan in the Battle of Okinawa. During 1942 and 1943, the US deployed millions of men and thousands of planes and tanks to the UK, beginning with the strategic bombing of Nazi Germany and occupied Europe and leading up to the Allied invasions of occupied North Africa in November, 1942, Sicily and Italy in 1943, France in 1944, and the invasion of Germany in 1945, parallel with the Soviet invasion from the east. That led to the surrender of Nazi Germany in May 1945. In the Pacific, the US experienced much success in naval campaigns during 1944, but bloody battles at Iwo Jima and Okinawa in 1945 led the US to look for a way to end the war with minimal loss of American lives. The U.S. used atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki to shock the Japanese leadership, which (combined with the Soviet invasion of Manchuria) quickly caused the surrender of Japan.

Despite the crippling effects of the Great Depression, the United States was able to mobilize quickly, eventually becoming the dominant military power in most theaters of the war (excepting only eastern Europe and mainland China), and the industrial might of the US economy is widely cited as a major factor in the Allies' eventual victory in the war. Early in the war, the US military was perceived by some observers to be too "green" and untested to be of much use other than cannon fodder against experienced German and Japanese troops (especially as their first major action against German forces resulted in the humiliating defeat at the Battle of the Kasserine Pass), but the US eventually acquitted itself well and established a modern military tradition. Strategic and tactical lessons learned by the US, such as the importance of air superiority and the dominance of the aircraft carrier in naval actions, continue to guide US military doctrine more than 65 years later.

World War II holds a special place in the American psyche as the country's greatest triumph, and the soldiers of World War II are frequently referred to as "the greatest generation" for their sacrifices in the name of liberty. Over 16 million served (about 11% of the population), and over 400,000 died during the war. The U.S. emerged as one of the two undisputed superpowers along with the Soviet Union, and unlike the Soviet Union, the US homeland was virtually untouched by the ravages of war. During and following World War II, the United States and Britain developed an increasingly strong, if one-sided, defence and intelligence relationship. Manifestations of this include extensive basing of US forces in the UK, shared intelligence, shared military technology (e.g. nuclear technology) and shared procurement.

Cold War era (1945–1991)

Following the World War II, the United States emerged as a global superpower vis-a-vis the Soviet Union in the Cold War. In this period of some forty years, the United States provided foreign military aid and direct involvement in proxy wars against the Soviet Union. It was the principal foreign actor in the Korean War and Vietnam War during this era. Nuclear weapons were held in ready by the United States under a concept of mutually assured destruction with the Soviet Union.

Postwar Military Reorganization (1947)

The National Security Act of 1947, meeting the need for a military reorganization to complement the U.S. superpower role, combined and replaced the former Department of the Navy and War Department with a single cabinet-level Department of Defense. The act also created the National Security Council, the Central Intelligence Agency, and the Air Force.

Korean War (1950–1953)

The Korean War was a conflict between the United States and its United Nations allies and the communist powers under influence of the Soviet Union (also a UN member nation) and the People's Republic of China (which later also gained UN membership). The principal combatants were North and South Korea. Principal allies of South Korea included the United States, Canada, Australia, the United Kingdom, although many other nations sent troops under the aegis of the United Nations. Allies of North Korea included the People's Republic of China, which supplied military forces, and the Soviet Union, which supplied combat advisors and aircraft pilots, as well as arms, for the Chinese and North Korean troops.[37]

The war started badly for the US and UN. North Korean forces struck massively in the summer of 1950 and nearly drove the outnumbered US and ROK defenders into the sea. However the United Nations intervened, naming Douglas MacArthur commander of its forces, and UN-US-ROK forces held a perimeter around Pusan, gaining time for reinforcement. MacArthur, in a bold but risky move, ordered an amphibious invasion well behind the front lines at Inchon, cutting off and routing the North Koreans and quickly crossing the 38th Parallel into North Korea. As UN forces continued to advance toward the Yalu River on the border with Communist China, the Chinese crossed the Yalu River in October and launched a series of surprise attacks that sent the UN forces reeling back across the 38th Parallel. Truman originally wanted a Rollback strategy to unify Korea; after the Chinese successes he settled for a Containment policy to split the country.[38] MacArthur argued for rollback but was fired. Peace negotiations dragged on for two years until President Dwight D. Eisenhower threatened China with nuclear weapons; an armistice was quickly reached with the two Koreas remaining divided at the 38th parallel. North and South Korea are still today in a state of war, having never signed a peace treaty, and American forces remain stationed in South Korea as part of American foreign policy.[39]

Lebanon crisis of 1958

In the Lebanon crisis of 1958 that threatened civil war, Operation Blue Bat deployed several hundred Marines to bolster the pro-Western Lebanese government from July 15 to October 25, 1958.

Dominican Intervention

Main article: Operation Power PackOn April 28, 1965, 400 Marines were landed in Santo Domingo to evacuate the American Embassy and foreign nationals after dissident Dominican armed forces attempted to overthrow the ruling civilian junta. By mid-May, peak strength of 23,850 U.S. soldiers, Marines, and Airmen were in the Dominican Republic and some 38 naval ships were positioned offshore. They evacuated nearly 6,500 men, women, and children of 46 nations, and distributed more than 8 million tons of food.

Vietnam War (1955–1975)

The Vietnam War a war fought between 1957 and 1975 on the ground in South Vietnam and bordering areas of Cambodia and Laos (see Secret War) and in the strategic bombing (see Operation Rolling Thunder) of North Vietnam. American advisors came in the late 1950s to help the RVN (Republic of Vietnam) combat Communist insurgents known as "Viet Cong." Major American military involvement began in 1964, after Congress provided President Lyndon B. Johnson with blanket approval for presidential use of force in the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution.

Fighting on one side was a coalition of forces including the Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam or the "RVN"), the United States, supplemented by South Korea, Thailand, Australia, New Zealand, and the Philippines. The allies fought against the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) as well as the National Liberation Front (NLF, also known as Viet communists Viet Cong), or "VC", a guerrilla force within South Vietnam. The NVA received substantial military and economic aid from the Soviet Union and China, turning Vietnam into a proxy war.

The U.S. framed the war as part of its policy of containment of Communism in south Asia, but American forces were frustrated by an inability to engage the enemy in decisive battles, corruption and incompetence in the Army of the Republic of Vietnam, and ever increasing protests at home. The Tet Offensive in 1968, although a major military defeat for the NLF with half their forces eliminated, marked the psychological turning point in the war. With President Richard M. Nixon opposed to containment and more interested in achieving détente with both the Soviet Union and China, American policy shifted to "Vietnamization," – providing very large supplies of arms and letting the Vietnamese fight it out themselves. After more than 57,000 dead and many more wounded, American forces withdrew in 1973 with no clear victory, and in 1975 South Vietnam was finally conquered by communist North Vietnam and unified.[40]

Memories and lessons from the war are still a major factor in American politics. One side views the war as a necessary part of the Containment policy, which allowed the enemy to choose the time and place of warfare. Others note the U.S. made major strategic gains as the Communists were defeated in Indonesia, and by 1972 both Moscow and Beijing were competing for American support, at the expense of their allies in Hanoi. Critics see the conflict as a "quagmire"--an endless waste of American blood and treasure in a conflict that did not concern US interests. Fears of another quagmire have been major factors in foreign policy debates ever since.[41] The draft became extremely unpopular, and President Nixon ended it in 1973,[42] forcing the military (the Army especially) to rely entirely upon volunteers. That raised the issue of how well the professional military reflected overall American society and values; the soldiers typically took the position that their service represented the highest and best American values.[43]

See also United States Air Force in Thailand.

Tehran hostage rescue

During and Iran hostage crisis, Operation Eagle Claw was an attempt to rescue the hostages. It failed because of inappropriate equipment, incomplete and unrealistic planning, and the lack of joint service training. The fiasco led directly to the creation of SOCOM.

Grenada

In October, 1983, a violent power struggle threatened American lives in the small Caribbean nation of Grenada. Neighboring nations asked the U.S. to intervene. The invasion was a hurriedly devised grouping of paratroopers, Marines, Rangers, and special operations forces in Operation Urgent Fury. Over a thousand Americans quickly seized the entire island, taking hundreds of military and civilian prisoners, especially Cubans.[44][45]

Beirut

In 1983 fighting between Palestinian refugees and Lebanese factions reignited that nation's long-running civil war. A UN agreement brought an international force of peacekeepers to occupy Beirut and guarantee security. US Marines landed in August 1982 along with Italian and French forces. On October 23, 1983, a suicide bomber driving a truck filled with 6 tons of TNT crashed through a fence and destroyed the Marine barracks, killing 241 Marines; seconds later, a second bomber leveled a French barracks, killing 58. Subsequently the US Navy engaged in bombing of militia positions inside Lebanon. While US President Ronald Reagan was initially defiant, political pressure at home eventually forced the withdrawal of the Marines in February 1984.

The attack on the US Marine barracks resulted in the single largest loss of life for the USMC since World War II.[citation needed]

In 2003, a judge for the United States District Court for the District of Columbia ruled that the Islamic Republic of Iran was responsible for the attack.[46]

Libya

Code-named "Operation El Dorado Canyon", comprised the joint United States Air Force, Navy and Marine Corps air-strikes against Libya on April 15, 1986. The attack was carried out in response to the 1986 Berlin discotheque bombing.

Panama

On December 20, 1989 the United States invaded Panama, mainly from U.S. bases within the then-Canal Zone, to oust dictator and international drug trafficker Manuel Noriega. American forces quickly overwhelmed the Panamanian Defense Forces, Noriega was captured on January 3, 1990 and imprisoned in the U.S. and a new government was installed.[47]

Post–Cold War era (1991–2001)

Persian Gulf War (1990–1991)

The Persian Gulf War was a conflict between Iraq and a coalition force of 34 nations led by the United States. The lead up to the war began with the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in August 1990 which was met with immediate economic sanctions by the United Nations against Iraq. The coalition commenced hostilities in January 1991, resulting in a decisive victory for the U.S. led coalition forces, which drove Iraqi forces out of Kuwait with minimal coalition deaths. Despite the low death toll, over 180,000 US veterans would later be classified as "permanently disabled" according to the US Department of Veterans Affairs (National Gulf War Resource Center; see also Gulf War Syndrome). The main battles were aerial and ground combat within Iraq, Kuwait and bordering areas of Saudi Arabia. Land combat did not expand outside of the immediate Iraq/Kuwait/Saudi border region, although the coalition bombed cities and strategic targets across Iraq, and Iraq fired missiles on Israeli and Saudi cities.[48]

Before the war, many observers believed the US and its allies could win but might suffer substantial casualties (certainly more than any conflict since Vietnam), and that the tank battles across the harsh desert might rival those of North Africa during World War II. After nearly 50 years of proxy wars, and constant fears of another war in Europe between NATO and the Warsaw Pact, some thought the Persian Gulf War might finally answer the question of which military philosophy would have reigned supreme. Iraqi forces were battle-hardened after 8 years of war with Iran, and they were well-equipped with late model Soviet tanks and jet fighters, but the anti-aircraft weapons were crippled; in comparison, the US had no large-scale combat experience since its withdrawal from Vietnam nearly 20 years earlier, and major changes in US doctrine, equipment and technology since then had never been tested under fire.

However, the battle was one-sided almost from the beginning. The reasons for this are the subject of continuing study by military strategists and academics. There is general agreement that US technological superiority was a crucial factor but the speed and scale of the Iraqi collapse has also been attributed to poor strategic and tactical leadership and low morale among Iraqi troops, which resulted from a history of incompetent leadership. After devastating initial strikes against Iraqi air defenses and command and control facilities on 17 January 1991, coalition forces achieved total air superiority almost immediately. The Iraqi air force was destroyed within a few days, with some planes fleeing to Iran where they were interned for the duration of the conflict. The overwhelming technological advantages of the US, such as stealth aircraft and infrared sights, quickly turned the air war into a "turkey shoot". The heat signature of any tank which started its engine made an easy target. Air defense radars were quickly destroyed by radar-seeking missiles fired from wild weasel aircraft. Grainy video clips, shot from the nose cameras of missiles as they zeroed in on impossibly small targets, were a staple of US news coverage and revealed to the world a new kind of war, compared by some to a video game. Over 6 weeks of relentless pounding by planes and helicopters, the Iraqi army was almost completely beaten but did not retreat, under orders from Iraqi President Saddam Hussein, and by the time the ground forces invaded on 24 February, many Iraqi troops quickly surrendered to forces much smaller than their own; in one instance, Iraqi forces attempted to surrender to a television camera crew that was advancing with coalition forces.

After just 100 hours of ground combat, and with all of Kuwait and much of southern Iraq under coalition control, US President George H. W. Bush ordered a cease-fire and negotiations began resulting in an agreement for cessation of hostilities. Some US politicians were disappointed by this move, believing Bush should have pressed on to Baghdad and removed Hussein from power; there is little doubt that coalition forces could have accomplished this if they had desired. Still, the political ramifications of removing Hussein would have broadened the scope of the conflict greatly, and many coalition nations refused to participate in such an action, believing it would create a power vacuum and destabilize the region.[49]

Following the Persian Gulf War, to protect minority populations, the US, Britain, and France declared and maintained no-fly zones in northern and southern Iraq, which the Iraqi military frequently tested. The no-fly zones persisted until the 2003 invasion of Iraq, although France withdrew from participation in patrolling the no-fly zones in 1996, citing a lack of humanitarian purpose for the operation.

Somalia

Main article: Operation Restore HopeUS troops participated in a UN peacekeeping mission in Somalia beginning in 1992. By 1993 the US troops were augmented with Rangers and special forces with the aim of capturing warlord Mohamed Farrah Aidid, whose forces had massacred peacekeepers from Pakistan. During a raid in downtown Mogadishu, US troops became trapped overnight by a general uprising in the Battle of Mogadishu. 18 American soldiers were killed, and a US television crew filmed graphic images of the body of one soldier being dragged through the streets by an angry mob. Somali guerrillas paid a staggering toll at an estimated 1,000–5,000 total casualties during the conflict. After much public disapproval, American forces were quickly withdrawn by President Bill Clinton. The incident profoundly affected US thinking about peacekeeping and intervention. The book Black Hawk Down was written about the battle, and was the basis for the later movie of the same name.[50]

Haiti

Operation Uphold Democracy (September 19, 1994 – March 31, 1995) was an intervention designed to remove the military regime installed by the 1991 Haitian coup d'état, which overthrew the elected President Jean-Bertrand Aristide. The operation was effectively authorized by the 31 July 1994 United Nations Security Council Resolution 940.[51]

Yugoslavia

During the war in Yugoslavia in the early 1990s, the US operated in Bosnia and Herzegovina as part of the NATO-led multinational implementation force (IFOR) in Operation Joint Endeavour . The USA was one of the NATO member countries who bombed Yugoslavia between March 24 and June 9, 1999 during the Kosovo War and later contributed to the multinational force KFOR.[52]

War on Terrorism (2001–present)

The War on Terrorism is a global effort by the governments of several countries (primarily the United States and its principal allies) to neutralize international terrorist groups (primarily radical Islamist terrorist groups, including al-Qaeda) and ensure that rogue nations no longer support terrorist activities. It has been adopted as a response to the September 11, 2001 attacks on the United States.

Afghanistan

The invasion of Afghanistan (Operation Enduring Freedom – Afghanistan) to depose that country's Taliban government and destroy training camps associated with al-Qaida is understood to have been the opening, and in many ways defining, campaign of the broader War on Terrorism. The emphasis on Special Operations Forces (SOF), political negotiation with autonomous military units, and the use of proxy militaries marked a significant change from prior U.S. military approaches.[53]

Philippines

In January 2002, the U.S. sent more than 1,200 troops (later raised to 2,000) to assist the Armed Forces of the Philippines in combating terrorist groups linked to al-Qaida, such as Abu Sayyaf, under Operation Enduring Freedom - Philippines. Operations are taking place mostly in the Sulu Archipelago, where terrorists and other groups are active. The majority of troops provide logistics; however, a sizable portion are Special Forces troops that are training and assisting in combat operations against the terrorist groups.

Iraq

After the lengthy Iraq disarmament crisis culminated with an American demand that Iraqi President Saddam Hussein leave Iraq, which was refused, a coalition led by the United States and the United Kingdom fought the Iraqi army in the 2003 invasion of Iraq. Approximately 250,000 United States troops, with support from 45,000 British, 2,000 Australian and 200 Polish combat forces, entered Iraq primarily through their staging area in Kuwait. (Turkey had refused to permit its territory to be used for an invasion from the north.) Coalition forces also supported Iraqi Kurdish militia, estimated to number upwards of 50,000. After approximately three weeks of fighting, Hussein and the Ba'ath Party were forcibly removed, followed by 9 years of military occupation by the United States.

Libyan intervention

As a result of the 2011 Libyan uprising, the United Nations enacted United Nations Security Council Resolution 1973, which imposed a no-fly zone over Libya, and the protection of civilians from the loyalist forces of Muammar Gaddafi. The United States, along with several other nations, committed a coalition force against Gaddafi's forces. On 19 March, the first U.S. action was taken when 114 Tomahawk missiles launched by US and UK warships destroyed shoreline air defenses of the Gaddafi regime.[54] The U.S. continued to play a major role in Operation Unified Protector, the NATO-directed mission that eventually incorporated all of the military coalition's actions in the theatre. Throughout the war, however, the Obama administration maintained that the U.S. was playing a supporting role only and was following the UN mandate to protect civilians, while the real conflict was between Gaddafi's loyalists and Libyan rebels fighting to depose him.[55][56] This doctrine was occasionally derided by some of Obama's detractors as "leading from behind", though others argued that it was a sensible approach that avoided some of the perceived pitfalls of the Iraq War strategy.[57]

After the Battle of Tripoli saw Gaddafi's grip on power broken, the U.S. sent at least four uniformed personnel to help protect and rebuild the battle-damaged U.S. Embassy in the Libyan capital, breaking an earlier promise it had made not to place "boots on the ground" in Libya.[58]

During the conflict, Libya was also a theatre of drone activity. Obama authorised the use of armed USAF drones by NATO forces one month into the military intervention,[59] and a General Atomics MQ-1 Predator participated in airstrikes that destroyed part of Gaddafi's convoy as it attempted to flee the fall of Sirte on 20 October 2011. Gaddafi, who survived the NATO attack but was found wounded by Misratan fighters hours later, died later that morning. It was unclear whether he succumbed to his injuries, was killed in a separate firefight, or was shot or beaten to death while in custody.[60][61]

See also

- United States Armed Forces

- United States and weapons of mass destruction

- United States Department of Defense

- Awards and decorations of the United States military

- United States casualties of war

History of minorities in the United States Armed Forces

Related lists

- Timeline of United States military operations

- United States military deployments

- List of conflicts in the United States

- List of military operations

- List of United States military leaders by rank

References

- ^ John Whiteclay Chambers, ed., The Oxford Guide to American Military History (1999)

- ^ Jeremy Black, America as a Military Power: From the American Revolution to the Civil War (2002)

- ^ Fred Anderson, ed. The Oxford Companion to American Military History (2000)

- ^ Spencer C. Tucker, James Arnold, and Roberta Wiener eds. The Encyclopedia of North American Colonial Conflicts to 1775: A Political, Social, and Military History (2008) excerpt and text search

- ^ James Titus, The Old Dominion at War: Society, Politics and Warfare in Late Colonial Virginia (1991)

- ^ Fred Anderson, The War That Made America: A Short History of the French and Indian War (2006)

- ^ Don Higginbotham, The war of American independence: military attitudes, policies, and practice, 1763–1789 (1983)

- ^ Lesson Plan on "What Made George Washington a Good Military Leader?" NEH EDSITEMENT

- ^ Edward G. Lengel, General George Washington: A Military Life (2007)

- ^ Richard H. Kohn, Eagle and Sword: The Federalists and the Creation of the Military Establishment in America, 1783–1802 (1975)

- ^ William B. Kessel and Robert Wooster, eds. Encyclopedia of Native American wars and warfare (2005) pp 50, 123, 186, 280

- ^ Michael A. Palmer, Stoddert's war: naval operations during the quasi-war with France (1999)

- ^ Frank Lambert, The Barbary Wars: American Independence in the Atlantic World (2007)

- ^ Walter R. Borneman, 1812: The War That Forged a Nation (2005) is an American perspective; Mark Zuehlke, For Honour's Sake: The War of 1812 and the Brokering of an Uneasy Peace (2006) provides a Canadian perspective.

- ^ Robert W. Merry, A Country of Vast Designs: James K. Polk, the Mexican War and the Conquest of the American Continent (2009) excerpt and text search

- ^ Justin Harvey Smith, The War with Mexico, Vol 1. (2 vol 1919), full text online; Smith, The War with Mexico, Vol 2. (1919). full text online of Pulitzer prize winning history.

- ^ K. Jack Bauer, The Mexican War, 1846–1848(1974); David S. Heidler, and Jeanne T. Heidler, The Mexican War. (2005)

- ^ Louis P. Masur, The Civil War: A Concise History (2011)

- ^ Benjamin Bacon, Sinews of War: How Technology, Industry, and Transportation Won the Civil War (1997)

- ^ Utley (1973)

- ^ Jim Leeke, Manila And Santiago: The New Steel Navy in the Spanish-American War (2009)

- ^ Graham A. Cosmas, An Army for Empire: The United States Army in the Spanish-American War (1998)

- ^ Richard W. Stewart, "Emergence to World Power 1898–1902" Ch. 15, in "American Military History, Volume I: The United States Army and the Forging of a Nation, 1775–1917", (2004)

- ^ {{cite web |url=http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/database/article_display.cfm?HHID=191 |title=The Philippines |author= |date=22 May 2011 |work=Digital History |publisher=[[Universtiy of Houston|accessdate=22 May 2011|quote=In December, Spain ceded the Philippines to the Untied States for $20 million. }}

- ^ William Braisted, United States Navy in the Pacific, 1897–1909 (2008)

- ^ Brian McAllister Linn, The Philippine War 1899–1902 (University Press of Kansas, 2000). ISBN 0-7006-0990-3

- ^ Henry J. Hendrix, Theodore Roosevelt's Naval Diplomacy: The U.S. Navy and the Birth of the American Century (2009)

- ^ James E. Hewes, Jr. From Root to McNamara: Army Organization and Administration, 1900–1963 (1975)

- ^ Paolo Coletta, Admiral Bradley A. Fiske and the American Navy (1979)

- ^ Charles Byler, "Pacifying the Moros: American Military Government in the Southern Philippines, 1899–1913" Military Review (May–June 2005) pp 41–45. online

- ^ Kendrick A. Clements, "Woodrow Wilson and World War I," Presidential Studies Quarterly 34:1 (2004). pp 62+. online edition

- ^ Anne Venzon, ed., The United States in the First World War: An Encyclopedia (1995)

- ^ Edward M. Coffman, The War to End All Wars: The American Military Experience in World War I (1998)

- ^ Germany and the Soviet Unions were not invited.

- ^ Emily O. Goldman, Sunken treaties (1994)

- ^ Jeffery S. Underwood, The wings of democracy: the influence of air power on the Roosevelt Administration, 1933-1941 (1991) pp 34-5

- ^ Allan R. Millett, "A Reader's Guide To The Korean War," Journal of Military History (1997) Vol. 61 No. 3; p. 583+ online version

- ^ James I. Matray, "Truman's Plan for Victory: National Self-Determination and the Thirty-Eighth Parallel Decision in Korea," Journal of American History, Sept. 1979, Vol. 66 Issue 2, pp 314–333, in JSTOR

- ^ Stanley Sandler, ed., The Korean War: An Encyclopedia (Garland, 1995)

- ^ Robert D. Schulzinger, Time for War: The United States and Vietnam, 1941–1975. (1997) online edition

- ^ Patrick Hagopian, The Vietnam War in American Memory: Veterans, Memorials, and the Politics of Healing (2009) excerpt and text search

- ^ George Q. Flynn, The draft, 1940–1973 (1993)

- ^ Bernard Rostker, I want you!: the evolution of the All-Volunteer Force (2006)

- ^ Vijay Tiwathia, The Grenada war: anatomy of a low-intensity conflict (1987)

- ^ Mark Adkin, Urgent Fury: The Battle for Grenada: The Truth Behind the Largest U.S. Military Operation Since Vietnam (1989)

- ^ CNN. http://www.cnn.com/2003/LAW/05/30/iran.barracks.bombing.[dead link]

- ^ Thomas Donnelly, Margaret Roth and Caleb Baker, Operation Just Cause: The Storming of Panama (1991)

- ^ Rick Atkinson, Crusade: The Untold Story of the Persian Gulf War (1994)

- ^ Marc J. O'Reilly, Unexceptional: America's Empire in the Persian Gulf, 1941–2007 (2008) p 173

- ^ John L. Hirsch and Robert B. Oakley, Somalia and Operation Restore Hope: Reflections on Peacemaking and Peacekeeping (1995)

- ^ John R. Ballard, Upholding democracy: the United States military campaign in Haiti, 1994–1997 (1998)

- ^ Richard C. Holbrooke, To End a War (1999) excerpt and text search

- ^ Christopher N. Koontz, Enduring Voices: Oral Histories of the U.S. Army Experience in Afghanistan, 2003–2005 (2008) online

- ^ "U.S. Steps Up Assault on Libya, Firing Four More Tomahawk Missiles at Air Defense Systems". FOX News. 20 March 2011. http://www.foxnews.com/world/2011/03/20/explosions-gunfire-heard-tripoli-allies-continue-military-strikes-libya/. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "Obama Says No Conflict in U.S. Policy, UN Libya Mandate". Bloomberg. 21 March 2011. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2011-03-21/obama-says-no-conflict-in-u-s-policy-un-libya-mandate-1-.html. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ Clemons, Steve (22 August 2011). "Libya: Huge Win for Libyans, A Win for Obama, Challenges Next". The Atlantic. http://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2011/08/libya-huge-win-for-libyans-a-win-for-obama-challenges-next/243913/. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ Hounshell, Blake (22 August 2011). "Was Libya worth it?". Foreign Policy. http://blog.foreignpolicy.com/posts/2011/08/22/was_libya_worth_it. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ Fishel, Justin (12 September 2011). "U.S. Boots on the Ground in Libya, Pentagon Confirms". FOX News. http://www.foxnews.com/politics/2011/09/12/us-boots-on-ground-in-libya-pentagon-confirms/. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ Hopkins, Nick (21 April 2011). "Drones can be used by Nato forces in Libya, says Obama". The Guardian. http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/apr/21/nato-wants-drones-target-misrata. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "U.S. Drone Involved in Final Qaddafi Strike, as Obama Heralds Regime's 'End'". FOX News. 20 October 2011. http://www.foxnews.com/politics/2011/10/20/obama-qaddafi-death-ends-long-and-painful-chapter-in-libya/. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "Gaddafi killed in hometown, Libya eyes future". Reuters. 21 October 2011. http://www.reuters.com/article/2011/10/21/libya-idUSL5E7LK68Y20111021. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

Further reading

Surveys

- Anderson, Fred, ed. The Oxford Companion to American Military History (2000)

- Boyne, Walter J. Beyond the Wild Blue: A History of the U.S. Air Force, 1947–2007 (2007) excerpt and text search, popular

- Chambers, ed. John Whiteclay. The Oxford Guide to American Military History (1999) ISBN 0-19-507198-0

- Futrell, Robert Frank. Ideas, Concepts, Doctrine: A History of Basic Thinking in the United States Air Force (2 vol. 1979)

- Doughty, Robert. American Military History and the Evolution of Western Warfare, (1996) ISBN 0-669-41683-5

- Hearn, Chester G. Air Force: An Illustrated History: The U.S. Air Force from 1910 to the 21st Century (2008), popular excerpt and text search

- Howarth, Stephen. To Shining Sea: A History of the United States Navy, 1775–1998 (1999) excerpt and text search; a standard history

- Love, Robert W. History of the U.S. Navy, 1775–1941 (1992) and History of the U.S. Navy, 1942–1991 (1992) vol 1 excerpt and text search; vol 2 excerpt and text search; a standard history

- Matloff, Maurice, ed. American Military History (1996) full text online; standard textbook used in ROTC

- Millett, Allan R., and Peter Maslowski. For the common defense: a military history of the United States of America (1984)

- Millett, Allan R. Semper Fidelis. A History of the United States Marine Corps (1991)

- Murray, Stuart. Atlas of American Military History (2005) ISBN 0-8160-5578-5

- Sweeney, Jerry K., and Kevin B. Byrne, eds. A Handbook of American Military History: From the Revolutionary War to the Present, (1997) ISBN 0-8133-2871-3

- Weigley, Russell Frank. The American Way of War: A History of United States Military Strategy and Policy, (1977) excerpt and text search

Pre 1775

- Anderson, Fred. The War That Made America: A Short History of the French and Indian War (2006) excerpt and text search

- Grenier, John. The First Way of War: American War Making on the Frontier, 1607–1814 (Cambridge University Press, 2005).

- Grenier, John. "Recent Trends in the Historiography on Warfare in the Colonial Period (1607–1765)," History Compass April 2010 Volume 8, Issue 4, pages 358–367, DOI: 10.1111/j.1478-0542.2009.00657.x

- Hirsch, Adam J. The Collision of Military Cultures in Seventeenth-Century New England," Journal of American History, 74 (1988): 1187–1212. in JSTOR

- Starkey, A. European and Native American Warfare, 1675–1815 (University of Oklahoma Press, 1998)

- Steele, Ian. Warpaths: Invasions of North America (Oxford University Press, 1994).

- Tucker, Spencer C., James Arnold, and Roberta Wiener eds. The Encyclopedia of North American Colonial Conflicts to 1775: A Political, Social, and Military History (2008) excerpt and text search

1775–1800

- Alden, John R. A History of the American Revolution (1989), general survey; strong on military (ISBN 0-306-80366-6)

- Black, Jeremy. America as a Military Power: From the American Revolution to the Civil War (2002) online edition

- Carp, E. Wayne. "Early American Military History: A Review of Recent Work", Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 94 (1986), pp. 259–84.

- Fremont-Barnes, Gregory, and Richard A. Ryerson, eds. The Encyclopedia of the American Revolutionary War: A Political, Social, and Military History (ABC-CLIO, 2006) 5 volume paper and online editions; 1000 entries by 150 experts, covering all topics

- Higginbotham, Don. The War of American Independence: Military Attitudes, Policies, and Practice, 1763–1789 (1971, 1983). an analytical history of the war online via ACLS Humanities E-Book.

- Lancaster, Bruce. The American Revolution (American Heritage Library) (ISBN 0-8281-0281-3) (1985), heavily illustrated

- Middlekauff, Robert. The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763–1789 (2nd ed 2007) online edition

1800–1860

- Bauer K. Jack. The Mexican War, 1846–1848. (1974), good on military action.

- Black, Jeremy. America as a Military Power: From the American Revolution to the Civil War (2002) online edition

- Crawford, Mark et al. eds. Encyclopedia of the Mexican War (1999) (ISBN 1-57607-059-X)

- Frazier, Donald S. ed. The U.S. and Mexico at War, (1998), 584; an encyclopedia with 600 articles by 200 scholars

- Heidler, Donald & Jeanne T. Heidler (eds) Encyclopedia of the War of 1812 (2nd ed 2004) 636pp; most comprehensive guide to this war; 500 entries by 70 scholars from several countries

- Heidler, David S. and Heidler, Jeanne T. The War of 1812. (2002). 217 pp. short survey

- Heidler, David S. and Heidler, Jeanne T. The Mexican War. (2005). 225 pp. basic survey, with some key primary sources

- Hickey, Donald R. Don't Give Up the Ship! Myths of the War of 1812. (2006)

- Hickey, Donald R. The War of 1812: A Forgotten Conflict. (1990), standard scholarly history

- Johnson, Timothy D. Winfield Scott: The Quest for Military Glory (1998)

- McCaffrey, James M. Army of Manifest Destiny: The American Soldier in the Mexican War, 1846–1848 (1994)excerpt and text search

- Quimby, Robert S., The US Army in the War of 1812: an operational and command study (1997) online version

- Roosevelt, Theodore. The Naval War of 1812 (1882) full text online, by the future president

- Smith, Justin H. The War with Mexico 2 vol (1919); Pulitzer Prize; 2:233-52; online vol 1; online vol 2 Pulitzer Prize winner.

- Winders, Richard Price. Mr. Polk's Army (1997) excerpt and text search, focus on the soldiers

Civil War

- Beringer, Richard E., Archer Jones, and Herman Hattaway. The Elements of Confederate Defeat: Nationalism, War Aims, and Religion (1988)

- Carter, Alice E. and Richard Jensen. The Civil War on the Web: A Guide to the Very Best Sites (2nd ed. 2003) excerpt and text search

- Catton, Bruce. Centennial History of the Civil War (3 vols. 1961–65); Catton has many very-well-written books on the war

- Current, Richard N., et al. eds. Encyclopedia of the Confederacy (1993) (4 Volume set; also 1 vol abridged version)

- Donald, David et al. The Civil War and Reconstruction (2001); 700 pages

- Faust, Patricia L., ed. Historical Times Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Civil War (1986) (ISBN 0-06-181261-7) 2000 short entries

- Fellman, Michael et al. This Terrible War: The Civil War and its Aftermath (2nd ed. 2007), 544 pages

- Heidler, David Stephen, ed. Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History (2002), 1600 entries in 2700 pages in 5 vol or 1-vol editions

- McPherson, James M. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (1988), 900 pages; excerpt and text search; also complete online edition, Pulitzer Prize; comprehensive history

- Nevins, Allan. Ordeal of the Union, an 8-volume set (1947–1971). the most detailed political, economic and military narrative; by Pulitzer Prize winner

- vol 1. Fruits of Manifest Destiny, 1847–1852; 2. A House Dividing, 1852–1857; 3. Douglas, Buchanan, and Party Chaos, 1857–1859; 4. Prologue to Civil War, 1859–1861; 5. The Improvised War, 1861–1862; 6. War Becomes Revolution, 1862–1863; 7. The Organized War, 1863–1864; 8. The Organized War to Victory, 1864–1865

- Rhodes, James Ford. History of the Civil War, 1861–1865 (1918), old, accurate survey; won Pulitzer prize

- Shannon, Fred. The Organization and Administration of the Union Army 1861–1865 (2 vol 1928) vol 1 excerpt and text search; vol 2 excerpt and text search

- Symonds, Craig L. and William J. Clipson. A Battlefield Atlas of the Civil War (1993) schematic maps that are easy to understand

1865–1917

- Abrahamson, James L. America Arms for a New Century: The Making of a Great Military Power (1981), examines reformers and modernizers

- Coffman, Edward M. The Old Army: A Portrait of the American Army in Peacetime, 1784–1898 (1986).

- Cosmas, Graham A. An Army for Empire: The United States Army and the Spanish–American War (1971), looks at organization, not combat

- Holmes, James R. Theodore Roosevelt and World Order: Police Power in International Relations. (2006).

- Trask, David F. The War with Spain in 1898 (1996), 654pp excerpt and text search, the most detailed scholarly coverage

- Utley, Robert M. Frontier Regulars; the United States Army and the Indian, 1866–1891 (1973)

World War I

- Chambers, John W., II. To Raise an Army: The Draft Comes to Modern America (1987)

- Coffman, Edward M. The War to End All Wars: The American Military Experience in World War I (1998), a standard history

- Freidel, Frank. Over There (1964), well illustrated history by scholar

- Hurley, Alfred F. Billy Mitchell, Crusader for Air Power (1975)

- Kennedy, David M. Over Here: The First World War and American Society (1982)

- Koistinen, Paul. Mobilizing for Modern War: The Political Economy of American Warfare, 1865–1919 (2004)

- Venzon, Anne ed. The United States in the First World War: An Encyclopedia (1995)

Interwar

- Coffman, Edward M. The Regulars: The American Army, 1898–1941 (2007) excerpt and text search

- Koistinen, Paul A. C. Planning War, Pursuing Peace: The Political Economy of American Warfare, 1920–1939 (1998) excerpt and text search

World War II

- Ambrose, Stephen. The Supreme Commander: The War Years of Dwight D. Eisenhower (1999) excerpt and text search

- James, D. Clayton. The Years of Macarthur 1941–1945 (1975), vol 2. of standard scholarly biography

- Koistinen, Paul A. C. Arsenal of World War II: the political economy of American warfare, 1940–1945? (2004)

- Larrabee, Eric. Commander in Chief: Franklin Delano Roosevelt, His Lieutenants, and Their War (2004), chapters on all the key American war leaders excerpt and text search

- Morison, Two-Ocean War: A Short History of the United States Navy in the Second World War (2007)

- Perret, Geoffrey. There's a War to Be Won: The United States Army in World War II (1997)

- Perret, Geoffrey. Winged Victory: The Army Air Forces in World War II (1997)

- Pogue, Forrest. George C. Marshall: Ordeal and Hope, 1939–1942 (1999); George C. Marshall: Organizer of Victory, 1943–1945 (1999); standard scholarly biography

- Potter, E. B. Nimitz. (1976).

- Sherrod, Robert Lee. History of Marine Corps Aviation in World War II (1987)

- Spector, Ronald. Eagle Against the Sun: The American War With Japan (1985)

- Weigley, Russell. Eisenhower's Lieutenants: The Campaigns of France and Germany, 1944–45 (1990)

- Weinberg, Gerhard L. A World at Arms: A Global History of World War II (1994). Global history of the war; strong on diplomacy of FDR and other main leaders

Cold War

- Atkins, Stephen E. Historical Encyclopedia of Atomic Energy. (2000). 491 pp.

- Bacevich, Andrew J., ed. The Long War: A New History of U.S. National Security Policy Since World War II (2007) excerpt and text search

- Bundy, McGeorge. Danger and Survival: Choices About the Bomb in the First Fifty Years (1988).

- Friedman, Norman. The Fifty Year War: Conflict and Strategy in the Cold War. (2000) excerpt and text search

- Gaddis, John Lewis. Strategies of Containment: A Critical Appraisal of Postwar American National Security Policy (1982) online edition; also excerpt and text search

- Goldfischer, David. The Best Defense: Policy Alternatives for U.S. Nuclear Security from the 1950s to the 1990s. (1993). 283 pp.

- Isenberg, Michael T. Shield of the Republic: The United States Navy in an Era of Cold War and Violent Peace 1945–1962 (1993)

- Lewis, Adrian R. The American Culture of War: The History of U.S. Military Force from World War II to Operation Iraqi Freedom (2006) excerpt and text search

- Williamson, Samuel R., Jr. and Reardon, Steven L. The Origins of U.S. Nuclear Strategy, 1945–1953. (1993). 224 pp.

Korea and Vietnam

- Brune, Lester H. ed. The Korean War: Handbook of the Literature and Research (1996) online edition

- Anderson, David L. Columbia Guide to the Vietnam War (2004).

- Herring, George C. America's Longest War: The United States and Vietnam, 1950–1975 (4th ed 2001), most widely used short history.

- Kutler, Stanley ed. Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War (1996). essays by experts

- Lewy, Guenter. America in Vietnam (1978), defends U.S. actions.

- Schulzinger, Robert D. Time for War: The United States and Vietnam, 1941–1975. (1997) online edition

- Tucker, Spencer. ed. Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War (1998) 3 vol. reference set; also one-volume abridgement (2001).

- Tucker, Spencer. Vietnam. (1999) 226pp. online edition

- Tucker, Spencer, ed. Encyclopedia of the Korean War (2002)

- The Pentagon Papers (Gravel ed. 5 vol 1971); combination of narrative and secret documents compiled by Pentagon. excerpts

Since 1990

External links

- Instances of Use of United States Forces Abroad, 1798–1993 by Ellen C. Collier, Specialist in U.S. Foreign Policy, Foreign Affairs and National Defense Division

- United States Military Campaigns, Conflicts, Expeditions and Wars Compiled by Larry Van Horn, U.S. Navy Retired

- Statistics of US foreign policy since 1945

- Military History wiki

- American Wars: A Photo Gallery

History of the United States Timeline Topics African American · Asian American · Demographic · Diplomatic · Economic · Education · Immigration · Jewish · Mexican American · Merchant Marine · Military · Musical · Religious · Southern · Stamps · Technological and industrial · Territorial acquisitions · Territorial evolution · Women Category ·

Category ·  Portal

PortalLeadership Commander-in-chief: President of the United States · Secretary of Defense · Deputy Secretary of Defense · Joint Chiefs of Staff (Chairman) · United States Congress: Committees on Armed Services: (Senate · House) · Active duty four-star officers · Highest ranking officers in history · National Security Act of 1947 · Goldwater–Nichols Act

Organization BranchesReserve componentsNorthern · Central · European · Pacific · Southern · Africa · Special Operations · Strategic · Transportation

Structure United States Code (Title 10 · Title 14 · Title 32) · The Pentagon · Installations (A · MC · N · AF · CG) · Budget · Units: (A · MC · N · AF · CG) · Logistics · Media

Operations and history Current deployments · Conflicts · Wars · Timeline · History: (A · MC · N · AF · CG) · Colonial · WWII · Civil affairs · African Americans · Asian Americans · Jewish Americans · Sikh Americans · Historiography: (A: 1/2 · MC · N · AF) · Art: (A · AF)

Personnel TrainingOtherOath: (Enlistment · Office) · Creeds & Codes: (Code of Conduct · NCO · A · MC · N · AF · CG) · Service numbers: (A · MC · N · AF · CG) · Military Occupational Specialty/Rating/Air Force Specialty Code · Pay · Uniform Code of Military Justice · Judge Advocate General's Corps · Military Health System/TRICARE · Separation · Veterans Affairs · Conscription · Chiefs of Chaplains: (A · MC · N · AF · CG)

Equipment LandSeaAirAircraft (WWI · active) · Aircraft designation · Missiles · Helicopter arms

OtherLegend: A = Army, MC = Marine Corps, N = Navy, AF = Air Force, CG = Coast Guard, PHS = Public Health Service, NOAA = National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, MSC = Military Sealift Command United States (Outline) History Pre-Columbian era · Colonial era (Thirteen Colonies · Colonial American military history) · American Revolution (War) · Federalist Era · War of 1812 · Territorial acquisitions · Territorial evolution · Mexican–American War · Civil War · Reconstruction era · Indian Wars · Gilded Age · African-American Civil Rights Movement (1896–1954) · Spanish–American War · Imperialism · World War I · Roaring Twenties · Great Depression · World War II (Home front) · Cold War · Korean War · Space Race · African-American Civil Rights Movement (1955–1968) · Feminist Movement · Vietnam War · Post-Cold War (1991–present) · War on Terror (War in Afghanistan · Iraq War) · Timeline of modern American conservatismTopicsDemographic · Discoveries · Economic (Debt Ceiling) · Inventions (before 1890 · 1890–1945 · 1946–1991 · after 1991) · Military · Postal · Technological and industrialFederal

governmentLegislature - Congress

Senate

· Vice President

· President pro tem

House of Representatives

· Speaker

Judiciary - Supreme Court

Federal courts

Courts of appeal

District courtsExecutive - President

Executive Office

Cabinet / Executive departments

Civil service

Independent agencies

Law enforcement

Public policy

Intelligence

Central Intelligence Agency

Defense Intelligence Agency

National Security Agency

Federal Bureau of InvestigationPolitics Divisions · Elections (Electoral College) · Foreign policy · Foreign relations · Ideologies · Local governments · Parties (Democratic Party · Republican Party · Third parties) · Political status of Puerto Rico · Red states and blue states · Scandals · State governments · Uncle SamGeography Cities, towns, and villages · Counties · Extreme points · Islands · Mountains (Peaks · Appalachian · Rocky) · National Park System · Regions (Great Plains · Mid-Atlantic · Midwestern · New England · Northwestern · Southern · Southwestern · Pacific · Western) · Rivers (Colorado · Columbia · Mississippi · Missouri · Ohio · Rio Grande) · States · Territory · Water supply and sanitationEconomy Agriculture · Banking · Communications · Companies · Dollar · Energy · Federal Budget · Federal Reserve System · Financial position · Insurance · Mining · Public debt · Taxation · Tourism · Trade · Transportation · Wall StreetSociety TopicsCrime · Demographics · Education · Family structure · Health care · Health insurance · Incarceration · Languages (American English · Spanish · French) · Media · People · Public holidays · Religion · SportsArchitecture · Art · Cinema · Cuisine · Dance · Fashion · Flag · Folklore · Literature · Music · Philosophy · Radio · Television · TheaterIssues Book ·

Book ·  Category ·

Category ·  Portal ·

Portal ·  WikiProject

WikiProjectMilitary history of North America Sovereign states Antigua and Barbuda · Bahamas · Barbados · Belize · Canada · Costa Rica · Cuba · Dominica · Dominican Republic · El Salvador · Grenada · Guatemala · Haiti · Honduras · Jamaica · Mexico · Nicaragua · Panama · Saint Kitts and Nevis · Saint Lucia · Saint Vincent and the Grenadines · Trinidad and Tobago · United States

Dependencies and

other territoriesAnguilla · Aruba · Bermuda · Bonaire · British Virgin Islands · Cayman Islands · Curaçao · Greenland · Guadeloupe · Martinique · Montserrat · Puerto Rico · Saint Barthélemy · Saint Martin · Saint Pierre and Miquelon · Saba · Sint Eustatius · Sint Maarten · Turks and Caicos Islands · United States Virgin Islands

Categories:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.