- Stephen Decatur

-

Stephen Decatur, Jr.

Born January 5, 1779

Sinepuxent, MarylandDied March 22, 1820 (aged 41)

Washington, D.C.Allegiance United States Service/branch United States Navy Years of service 1798–1820 Rank Commodore (USN) Commands held USS Argus,

USS Enterprise,

USS Chesapeake,

USS United States,

USS President,

USS Constitution,

USS GuerriereBattles/wars - Captured the Tripolian ketch, Mastico

- Battle of Tripoli Harbor

- Action of 11 October 1812

- USS United States vs. HMS Macedonian

- Capture of USS President

Awards Congressional Medal of Honor Other work Board of Navy Commissioners Stephen Decatur, Jr. /dɪˈkeɪtər/, (5 January 1779 – 22 March 1820) was an American naval officer notable for his many naval victories in the early 19th century. He was born on the eastern shore of Maryland, Worcester county, the son of a U.S. Naval Officer who served during the American Revolution. Shortly after attending college Decatur aptly followed in his father's footsteps and joined the U.S. Navy at the age of 19. [1] He was the youngest man to reach the rank of captain in the history of the United States Navy. [2] [3] Decatur's father, Stephan Decatur Sr., was also a Commodore in the U.S. Navy which brought the younger Stephen into the world of ships and sailing early on. Decatur supervised the construction of several U.S. naval vessels, one of which he would later take command of. He was affluent among Washington society and was personal friends with James Monroe and other Washington dignitaries. [4]

Decatur joined the U.S. Navy in 1798 as a midshipman [5] and served under three presidents, playing a major role in the development of the young American Navy. In almost every theater of operation Decatur's service was characterized with acts of heroism and exceptional performance in the many areas of military endeavor. His service in the Navy took him through the first and second Barbary Wars of north Africa, the Quasi-War with France, and the War of 1812 with Britain. During this period of time he served aboard and commanded many naval vessels and ultimately became a member of the Board of Navy Commissioners. He built a large home in Washington, known as Decatur House, on Lafayette Square, which later became the home to a number of famous Americans, and was the center of Washington society in the early 19th century. [6] He was renowned for his natural ability to lead and for his genuine concern for the seaman under his command. Decatur's distinguished career in the Navy would come to a premature end when he lost his life in a duel with a rival officer. [7][8] His numerous naval victories against Britain, France and the Barbary states established the United States as a world power comparable to Britain and France. Decatur subsequently emerged as a national hero in his own lifetime, becoming the first post revolutionary war hero where his name and legacy, like that of John Paul Jones, soon came to be identified with the United States Navy. [9] [10]

Early life

Stephen Decatur was born on January 5, 1779, in Sinepuxent, Maryland, to Stephen Decatur, Sr. and his wife Priscilla (Pine) Decatur. The family of Decatur was of French descent on Stephen's father's side while his mother's family was of Irish ancestry. [11] His parents had arrived from Philadelphia just three months before Stephen was born, having to flee that city during the American Revolution because of the British occupation, returning to the same residence they had once left for Philadelphia. [12] Decatur's father was Captain Stephen Decatur, Sr., an Officer in the young American navy during the American Revolution.

Decatur came to love the sea and sailing in a roundabout manner. When Stephen was eight years old he developed a severe case of whooping cough. In those days a known tonic for this condition was exposure to the salt-air of the sea. It was so decided that Stephen Jr. would accompany his father aboard a merchant ship on his next voyage to Europe. Sailing across the Atlantic and back proved to be an effective remedy and Decatur came home completely recovered. In the days following young Stephen's return he was jubilant about his adventure on the high sea and spoke of wanting to go sailing often. His parents had different aspirations, especially his mother who had hopes that Stephen would one day become an Episcopal clergyman, and tried to discourage the eight year old from such jaunty ambitions fearing they would distract Stephen from his studies. [13] [14]

At the direction of his father, Decatur attended the Protestant Episcopal Academy, [15] at the time an all boys school that specialized in Latin, mathematics and religion; however, Decatur had not applied himself adequately, and barely graduated from the academy. He then enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania in 1795 for one year [16] where he better applied himself and focused on his studies. At the university Decatur met and became friends with Charles Stewart and Richard Somers, who would later become naval officers themselves. [17]

Decatur found the classic studies prosaic and life at the University disagreeable, and at the age of 17, with his heart and mind set on ships and the sea, discontinued his studies there. Though his parents were not pleased with his decision they were apparently wise enough to now let the aspiring young man pursue his own course through life. [18] Through his father's influence Stephen gained employment at the shipbuilding firm of Gurney and Smith, business associates of his father, acting as supervisor to the early construction of the frigate United States. [19] [20] He was serving on board this vessel when it was launched on 10 May 10, 1797. [14]

He later served as a Midshipman on board this vessel under Commodore John Barry. [21] Stephen proved to be diligent in the performance of his duties there and quickly learned about ships, cargoes and the various duties expected of seamen, while at the same time he would study mathematics in his leisure time which he had previously neglected while at the University. He also had a talent for drawing ships and designing and building ship models and when time allowed would also pursue this hobby.[22] [23]

Pre-commission

In March of 1796, construction of new American frigates slowly progressed. However, because of a peace accord made with Algeria, construction on all six ships was halted. After some debate and at the insistence of George Washington, Congress passed an act on 20 April 1796 allowing the construction and funding to continue only on the three ships nearest to completion which at the time were USS United States, USS Constellation and the USS Constitution.[24]

In 1798, following in the footsteps of his father, Stephen Decatur, Sr., John Barry (naval officer) obtained Decatur's appointment as midshipman on the USS United States, under Barry’s command. Barry was a veteran and hero in the Revolutionary War and was Decatur’s good friend and mentor. Decatur accepted the appointment on May 1st.[25]

To ensure his son’s success in his naval career, Captain Decatur, Sr. hired a tutor, Talbot Hamilton, a former officer of the Royal Navy, to instruct his son in navigational and nautical sciences. While serving aboard the United States Decatur received what was the equivalent to formal naval training not only from Hamilton but through active service aboard a commissioned ship, which is something that distinguished the young midshipman from many of his contemporaries.[26] [27]

Decatur’s father was given command of USS Delaware, which sailed along with United States and searched for and pursued French privateers along the coast and at high sea. [28] Several French Merchantmen vessels were captured and in one encounter a ship was sunk with the French captain ending up in the water. Midshipman Decatur came to the periled captain's aid and pulled him from the water.[29]

Quasi-War

In the years leading up to the Quasi War, an undeclared naval war with France involving disputes over U.S. trading and shipping with Britain, the U.S. Congress passed the 'Act to provide for a Naval Armament' and on March 27, 1794. It was promptly signed by George Washington that same day. There was much opposition to the bill and it was amended and allowed to pass with the condition that work on the proposed ships would stop in the event that peace with Algiers was obtained. [30] From 1798 to 1800 Decatur saw service throughout this conflict. After the American Revolution came to a close there were few American ships capable of defending the American coastline, much less of protecting American merchant ships at sea and abroad. What few ships that were available were converted into merchant ships. Now that America had won independence and no longer had the protection of Britain it was at once faced with the task of protecting her own ships and interests which were now being threatened by France in particular along with the Barbary pirates of North Africa. [31] The French were outraged that America was still involved in trading with Britain, a country with whom they were at war and because of American refusal to pay a debt that was owed to the French crown, which had just been overthrown by the newly established French Republic. As a result France began intercepting American ships that were involved in trading with Britain.[32] [33] This provocation prompted president Adams to appoint Benjamin Stoddert as the first Secretary of the Navy who immediately ordered his senior commanders to "subdue, seize and take any armed vessel or vessels sailing under the authority or pretense of authority, from the French Republic." [33] At this time there were no America naval commanders that could measure up to Decatur's performance and distinction, moreover, America was not even ranked with European naval forces.[34]

On May 21, 1799, Decatur was promoted to Lieutenant after serving for more than a year as midshipman aboard the frigate United States. He received orders to sail to Philadelphia with the United States for repairs to incidental damage the vessel had incurred over the last year. While the ship was still undergoing repairs Decatur received orders to remain in Philadelphia to recruit and assemble a crew for the vessel. While there the Chief mate of an Indiaman vessel, using foul language, made several derogatory remarks about Decatur and the U.S. Navy. The incident was brought on over the chief mate losing some of his seaman to Decatur's recruiting efforts. Decatur remained calm and left the scene without further incident. Upon relating the matter to his father, Captain Stephen Decatur Sr., he stressed that the honor of the family and of the Navy had been insulted and that he should return and challenge the Chief mate to a duel. Before this was to occur however Lieutenant Somers was sent ahead with a letter from Decatur asking if an apology could be obtained from the mate. After refusing to apologize the Chief mate soon accepted Decatur's challenge. In the mean time the United States sailed south on the Delaware river to New Castle for final preparations. Also arriving was the Indiaman, also ready for sea. After anchoring his ship next to the American frigate the Chief mate came aboard the American ship to accept Decatur's challenge. Both duelists went ashore and secured a location for the duel. Decatur being an expert shot with a pistol had told his friend Lieutenant Charles Stewart that he believed his opponent not to be as able and would thus only wound his opponent in the hip, which is exactly how the duel turned out. The honor and courage of both duelists having been satisfied, the matter was resolved without the price of death.[35] [36]

On July 1, 1799, the United States was now refitted and repaired and commenced its mission to sail along and patrol the south Atlantic coast in search of French ships who were preying on American merchant vessels, especially in the West Indies. After its mission the ship was brought to Norfolk, Virginia, for other minor repairs and then set sail for Newport, Rhode Island arriving September 12. While berthed here Barry received orders to prepare for a voyage to transport two U.S. envoys to Spain and on December 3rd sailed in the United States for Lisbon, with England scheduled as the first stop. On this voyage the ship had encountered gale force winds and at the insistence of the two envoys were dropped off at the nearest port in England.[37] After returning home and arriving at the Delaware River on April 3, 1800, it was discovered that the United States had incurred damage from the storms she had weathered at sea. Consequently the vessel was taken up the Delaware river to Chester, Pennsylvania, for repairs.[38] Not wanting to remain with the United States during the months of her repairs and outfitting for her next mission Decatur obtained a transfer to the brig USS Norfolk[39] under the command of Thomas Calvert. In May the Norfolk sailed to the West Indies to patrol its waters looking for French privateers and men-of-war. During the few months that followed 25 armed enemy craft were captured or destroyed. During one engagement Captain Calvert was severely wounded. With orders to receive merchantmen bound for America the Norfolk continued on to Cartegena with orders to escort the ships back to the United States, protecting them from the pirates and privateers that preyed in these waters.[40]

Decatur soon transferred back to the United States which by June of 1800 was repaired and with extra guns and sails and improved structure the refurbished ship made her way down the Delaware River. Aboard ship at this time were Decatur's former classmates Lieutenant Charles Stewart and Midshipman Richard Somers along with Lieutenant James Barron.[41]

Following the Quasi-War, the U.S. Navy underwent a significant reduction of active ships and officers; Decatur was one of the few selected to remain commissioned. By the time hostilities with France came to a close, America had a renewed appreciation for the value of a navy. By 1801 the American Navy consisted of forty-two Naval vessels, three of which were the President, the Constellation and the Chesapeake.[42]

See main Article: Quasi-War First Barbary War

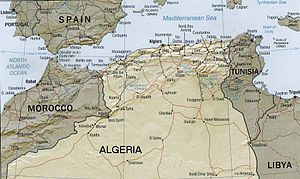

The first Barbary war of 1801 was in response to the frequent piracy of American vessels in the Mediterranean Sea and the capture and enslavement of American crews for huge ransoms. President Jefferson, known for his aversion to standing armies and the navy, acted contrary to such sentiment and began his presidency by expanding U.S. naval forces rather than pay huge annual tributes to the lawless Barbary states. On May 13, at the beginning of the war, Decatur was assigned duty aboard the frigate USS Essex to serve as the first lieutenant. The Essex, bearing 32 guns, was commanded by William Bainbridge and was attached to Commodore Richard Dale's squadron [43] which also included the Philadelphia, the President and the Enterprise. Departing for the Mediterranean on June 1, 1801, this squadron was the first American naval force to cross the Atlantic.[44] [45]

On July 1, after encountering and being forestalled by adverse winds, the squadron sailed into the Mediterranean with the mission to confront the Barbary pirates operating out of North Africa who were routinely attacking American shipping, stealing cargoes and often holding crews for huge ransoms. Arriving at Gibraltar Commodore Dale learned that Tripoli had already declared war. At this time there were two Tripolian warships of sizable consequence berthed in Gibraltar's harbor, but their captains claimed that they had no knowledge of the war. Dale assumed they were about to embark on the Atlantic to prey on American merchant ships. With orders to sail for Algiers, Tunis and Tripoli, Dale ordered that the Philadelphia be left behind to guard the Tripolian vessels.[46] [47]

In September of 1802 Decatur served aboard a 36-gun frigate, the USS New York, as 1st Lieutenant under Commodore James Barron in the Mediterranean. While enroute to Tripoli the five ship squadron Decatur was attached to encountered gale force winds, lasting more than a week, which forced the squadron to put up in Malta. While there Decatur and another U.S. Naval office were involved in a personal confrontation with a British officer stationed there which resulted in Decatur returning to the United States to take command of the newly built USS Argus. [48] Sailing from America to Gibraltar in the Argus, he then relinquished command of the ship and gave it to Lieutenant Isaac Hull. Decatur was then given command of the USS Enterprise, a 12-gun schooner. [49]

On December 23, 1803, the USS Enterprise along with the USS Constitution confronted the Tripolian ketch Mastico sailing under Turkish colors, armed with only two guns and sailing without passports on its way to Constantinople from Tripoli. On board were a small number of Tripolian soldiers. After a brief sortie Decatur and his crew captured the ship, killing or wounding what few men were there defending the vessel. After its capture the small ship was taken to Syracuse, condemned by Preble as a legitimate prize of war and was given a new name, the Intrepid, whose command was then given to Decatur. [50][51] [52]

Burning of the USS Philadelphia

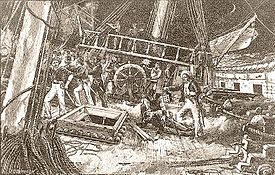

In command of the captured and newly named ship, the Intrepid, Decatur used this vessel to capture and set afire the USS Philadelphia in 16 February 1804, which had been captured by Tripolian forces after it ran aground on an uncharted reef near Tripoli's harbor on 31 October 1803, then under the command of Commodore William Bainbridge. In an elaborate plan put together by Commodores Preble and Bainbridge, [53] Deactur, with eighty volunteers from the Intrepid and the Syren [Note 1] sailed for Tripoli with their plan to enter the harbor with the Intrepid without suspicion for use to board and set ablaze the frigate USS Philadelphia. The Syren, commanded by Lieutenant Charles Stewart, accompanied the Intrepid to offer supporting fire during and after the assault. Before entering the harbor, eight sailors from the Syren boarded the Intrepid, including Thomas Macdonough who had recently served aboard the Philadelphia and knew the ship's layout intimately.[55]

On 16 February 1804, at seven o'clock in the evening under the dim light of a new moon the Intrepid, slowly sailed into Tripoli harbor, while the men hidden below were in position and prepared to board the captured Philadelphia. Decatur's vessel was made to look like a common merchant ship from Malta and was outfitted with British colors. To further evade suspicion, on board was one Salvador Catalono from Sicily who spoke Arabic. As Decatur's ship came closer to the Philadelphia Catalano called out to the harbor personnel in Arabic that their ship had lost its anchors during a recent storm and was seeking refuge at Tripoli for repairs. [56] By 9:30 Decatur's ship was within 200 yards of the Philadelphia, whose lower yards were now resting on the deck with her foremast missing, as Bainbridge had ordered it cut away and had jettisoned some of her guns in a futile effort to refloat the ship by lightening her load. [57] [58] After obtaining permission, Decatur docked and tied the Intrepid next to the captured Philadelphia. The men were divided into groups, each one assigned to secure given areas of the Philadelphia, with the explicit instructions refraining the use of firearms unless it proved absolutely necessary. [59]

As Decatur approached the berthed Philadelphia he encountered a light wind that made his approach tedious. He had to casually position his ship close enough to the Philadelphia to allow his men to board while not creating any suspicion. When the two vessels were finally close enough, Decatur surprised the few Tripolians on board at which point he shouted the order "board!", signaling to the hidden crew below to emerge and storm the captured ship. [60] Without losing a single man, Decatur and 60 of his men, dressed as Maltese sailors or Arab seamen and armed with swords and boarding pikes, boarded and reclaimed the Philadelphia in less then 10 minutes, killing at least 20 of the Tripolian crew, capturing one, and forcing the rest to flee by jumping overboard. Only one of Decatur's men was slightly wounded by a saber blade. There was hope that the small boarding crew could launch the captured ship, but the vessel was in no condition to set sail for the open sea. Commodore Preble's order to Decatur was to destroy the ship where she berthed. With the ship now secure, Decatur's crew began placing combustibles about the ship with orders to set her ablaze. After making sure the fire was large enough to sustain itself, Decatur abandoned the ship and was the last American and the last man to set foot on the Philadelphia. [61] [62] As the flames intensified the guns aboard Philadelphia, all loaded and ready for battle, became heated and began discharging, some firing into the town and shore batteries, while the ropes securing the ship burned off, allowing the vessel to drift into the rocks at the western entrance of the harbor.[63]

While Intrepid was under fire from the Tripolians who were now gathering along the shore and in small boats, the larger Syren was nearby returning support fire at the Tripolian shore batteries and gunboats. Decatur and his men left the burning vessel in Tripoli's harbor and set sail for the open sea, barely escaping in the confusion, and with the cover of night helping to obscure the sighting of enemy gun fire the Intrepid made her way back to Syracuse, arriving February 18. [64] [65] After learning of Decatur's daring capture and destruction of the Philadelphia Vice Admiral Lord Horatio Nelson of Britain who at the time was blockading the French port at Toulon, claimed that it was "...the most bold and daring act of the Age." [66] [67] Decatur's daring and successful burning of the Philadelphia made him an immediate national hero. [68] [69] Appreciation for the efforts of Preble and Decatur were not limited to their peers and countrymen. At Naples Decatur was praised and dubbed with the title 'Terror of the foe' . Upon hearing the news of their victory in Tripoli the Pope publicly declared "...the United States, though in their infancy, had done more to humble the anti-Christian barbarians on the African coast, than all the European states had done for a long period of time." [70] Upon his return to Syracuse Decatur resumed command of the Enterprise. [71]

Second attack on Tripoli

With the significant victory achieved at Tripoli with the burning of the Philadelphia, Preble now had reason to believe that bringing Tripoli to peaceful terms was in sight. Preble planned another attack on Tripoli and amassed a squadron, assigning a division of nine gunboats to Decatur. Preble in command his squadron consisted of the Constitution and the brigs Syren, Argus and Scourge and the schooners Nautilus, Vixen and Enterprise, towing gunboats and ketches, made their way into the West end of Tripoli harbor and began the bombarding of Tripoli on August 3, 1804. [72] The Kingdom of Sicily at this time was also at war with Tripoli and offered two gunboats to assist in the coming attack. [73] Preble divided his squadron of gunboats into two divisions, putting Decatur in command of the second division. At 1:30 Preble raised his signal flag to begin the attack on Tripoli. It was elaborate and well planned, brigs, schooners and bomb ketches, coming into the attack at various stages. [74] Bashaw Murad Reis of Tripoli was expecting the attack and had his gunboats lined up and waiting at various locations within the harbor. [75] [76]

The Tripolians inflicted considerable damage on some of the attacking vessels, Decatur's ship struck with a 24 pound shot through her hull. Before the battle ended the USS John Adams, commanded by Isaac Chauncey, appeared on the scene. The vessel had on board Decatur's official documents promoting him to the rank of captain. The John Adams also brought news that, upon the loss of the Philadelphia, the government was sending four frigates, the President, the Congress, the Constellation and the Essex to Tripoli with enough force to convince the Bey of Tripoli that peace was his only viable alternative. Because Preble's command was not high enough for this advent the John Adams also brought the news that he would have to surrender command to Commodore Barron.[77]

The fighting between the squadrons and the bombarding of Tripoli lasted three hours with Preble's squadrons emerging victorious. [78] Decatur's success and his promotion however were overshadowed by an unexpected turn of events. During the fighting, Decatur's younger brother, James Decatur, in command of a gunboat, was mortally wounded by a Tripolian captain during a boarding assault from the crew of a vessel pretending to surrender. [79] [80] Midshipman Brown, who was next in command after James, managed to break away with their vessel and immediately approached Decatur's gunboat bringing the news of the assault and of his brother's death. Decatur had just captured his first Tripolian vessel. Upon receiving the news Decatur turned command of his captured prize over to Lieutenant Jonathan Thorn and immediately set out on his own vessel to avenge his brother's treacherous death. [81] [82]After catching up with and pulling alongside the Tripolian ship involved, Decatur was the first to board the enemy vessel, with Midshipman Macdonough at his heels along with nine volunteer crew members. Decatur and his crew were outnumbered 5 to 1 but were organized and kept their form, fighting furiously side by side. [83] Finally, with little trouble, Decatur was now able to single out the captain and the man responsible for James' death and immediately engaged the man. He was a large and formidable man in Muslim garb and armed with a boarding pike he thrust his weapon at Decatur's chest. Armed with a cutlass Decatur deflected the lunge, breaking his own weapon at the hilt. [84] During the fight Decatur was almost killed by another Tripolian crew member, but his life was spared by the already wounded Daniel Frazier,[85] [86] [Note 2] a crewman who threw himself over Decatur just in time, receiving a blow intended for Decatur to his own head. The struggle continued, with the Tripolian captain, being larger and stronger than Decatur, gaining the upper hand. Armed with a dagger the Tripolian attempted to stab Decatur in the heart, but while wresting the arm of his adversary, Decatur managed to take hold of his pistol and fired a shot point-blank, immediately killing his formidable foe. When the fighting was over, 21 Tripolians were dead with only three taken alive. [89][90]

Later James Decatur's body was taken aboard the Constitution where he was joined by his brother Stephen who stayed with him until he had died. The next day, after a funeral and military ceremony that was conducted by Preble, Stephen Decatur would see his brother remains committed to the depths of the Mediterranean.[91]

When a good number of days passed without the reinforcements of ships promised by president Jefferson, the attack on Tripoli was renewed by Preble on August 24th. As the days passed Tripoli showed no signs of surrender which now prompted Preble to devise another plan. Using the 'Intrepid', the same ship that captured the Philadelphia, it was loaded with barrels of gunpowder and other ordnance and sent sailing into a group of Tripolian vessels defending the harbor. The attack on the Harbor and Tripoli proved successful and ultimately caused the Bashaw of Tripoli to consider surrender and the return of American prisoners held captive, including Commodore Bainbridge of the Philadelphia, who had been held prisoner since October of 1803 when that ship was captured after running aground near Tripoli harbor. On June 4, 1805, the Bashaw of Tripoli finally surrendered and signed a peace treaty with the United States.[92]

See main Article: First Barbary War Command of USS Constitution

Shortly after Decatur's recapture and destruction of the Philadelphia Decatur was given command of the frigate USS Constitution, commanding from October 28 to November 9, 1804. [93] [94] Upon the day of Decatur's return with the Intrepid, Commodore Preble wrote to Secretary of the Navy Benjamin Stoddert recommending to President Jefferson that Decatur be promoted to captain. Consequently in 1804 Decatur was promoted to this rank at the age twenty-five, largely for his daring capture and destruction of the Philadelphia in Tripoli's harbor, making him the youngest man ever to hold the rank.[95] [96] [97]

On September 10, 1804, Commodore Barron arrived at Tripoli with two ships, the President and the Constellation whereupon Commodore Preble relinquished command of his blockading squadron to him. Before returning to the United States he sailed to Malta in the Constitution on September 14, so it could be caulked and refitted. From there he sailed to Syracuse in the Argus where on September 24, he ordered Decatur to sail this vessel back to Malta to take command of the Constitution. From here Decatur sailed the Constitution back to Tripoli to join the Constellation and the Congress, the blockading force stationed there now under the command of Commodore Barron. On November 6, he relinquished command of the Constitution to Commodore John Rodgers, his senior, in exchange for the smaller vessel Congress. In need of new sails and other repairs Rodgers sailed the Constitution to Lisbon on November 27, where it remained for approximately six weeks. [98] [99]

Marriage

On March 8, 1806, Decatur married Susan Wheeler, the daughter of the Mayor of Norfolk, Virginia, Luke Wheeler, who was well known for her beauty and intelligence among Norfolk and Washington society. They had met at a dinner and ball held by the Mayor for a Tunisian ambassador who was in the United States negotiating peace terms for his country's recent defeat at Tunis under the silent guns of John Rodgers and Stephen Decatur. [100] [101] Before marrying Susan Decatur had already made vows to serve in the U.S. Navy and maintained that to abandon his service to his country for personal reasons would make him unworthy of her hand. Susan was once pursued by Vice President Aaron Burr and Jérôme Bonaparte, brother to Napoleon both of whom she had turned down. For several months after their marriage the couple resided with Susan's parents in Norfolk after which time Stephen received orders sending him to Newport to supervise the building of gunboats.[102][103][104] For reasons not clear to historians the couple would never have any children during their fourteen years of marriage. [105]

Supervision of shipbuilding

In the Spring of 1806 Decatur was given command of a squadron of gunboats stationed in the Chesapeake Bay at Norfolk, Virginia, the home of his future wife, Susan Wheeler. He had long requested such an assignment, however; one of his colleges believed that his request was also motivated by a desire to be close to Wheeler. While stationed here Decatur took the opportunity to court Miss Wheeler, whom he would soon marry that year. After their marriage in March, Decatur lived with his wife's family in Norfolk until June when Secretary of the Navy Robert Smith gave him orders to supervise the building of four gunboats at Newport, Rhode Island and four others in Connecticut which he would later take command of. Having drawn many illustrations of and designed and built many models of ships, along with having experience as a ship builder and designer from when he was employed at 'Gurney and Smith' in 1797 while overseeing the construction of the frigate the United States, Decatur was a natural choice for this new position. Decatur and his wife Susan lived together all through this period.[106][107][108]

Chesapeake-Leopard affair

After overseeing the completion of gunboats Decatur returned to Norfolk in March of 1807 and was given command of the Naval Yard at Gosport. While commissioned there he received a letter from the residing British consul to turn over three deserters from the British ship Melampus who had enlisted in the American Navy through Lieutenant Sinclair, who was recruiting crew members for the Chesapeake, which was at this time in Washington being outfitted for its coming voyage to the Mediterranean. [109] [110] Since the recruiting party was not under the command of Decatur, he refused to intervene. Sinclair also declined to take any action, claiming that he did not have the authority or any such orders from a superior officer. The matter was then referred to the British minister at Washington, a Mr. Erskine, who in turn referred the matter to the Navy Department through Commodore Barron, demanding that the three deserters be surrendered to British authority. It was soon discovered that the deserters were Americans who were forcibly impressed into the British Navy, and since the existing American treaty with Britain only pertained to criminal fugitives of justice, not deserters in the military, Barron accordingly also refused to turn them over. [111]

Soon thereafter the Chesapeake left Norfolk, and after stopping briefly at Washington for further preparations, set sail for the Mediterranean on June 22nd. In little time she was pursued by HMS Leopard which at the time was part of a British squadron in Lynnhaven Bay. Upon closing with the Chesapeake, Barron was hailed by the captain of the Leopard and informed that a letter would be sent on board with a demand from Vice-Admiral Humphreys that the Chesapeake be searched for deserters. Barron found the demand extraordinary and when he refused to surrender any of his crew, the Leopard soon opened fire on the Chesapeake. Having just put to sea, the Chesapeake was not prepared to do battle and was unable to return fire. Inside twenty minutes, three of her crew were killed and eighteen wounded. Barron struck the colors [Note 3] and surrendered his ship, whereupon she was boarded and the alleged deserters were taken into British custody. Not having any other designs on the Chesapeake, Humphreys allowed Barron to proceed with his ship at his own discretion, where he had little choice but to return home with the battered vessel, reaching Hampton Roads on June 23 with twenty-two shots through her hull, crippled fore- and mainmasts and more than three feet of water in her hold. [112] News of the incident soon reached President Jefferson, the Department of the Navy, and the general population in America. As commander at Gosport, Decatur in particular was outraged over the incident as he was the one who was first confronted with the matter. The incident soon came to be referred to as the Chesapeake-Leopard Affair, [113] [114] [115] an event whose controversy would lead to a duel between Barron and Decatur some years later, as Decatur served on Barron's court-martial and later was one of the most outspoken critics of questionable handling of the Chesapeake. [116] [117]

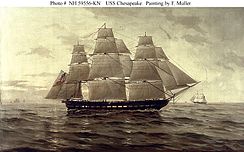

Command of USS Chesapeake

On June 26, 1807 Decatur was appointed command of the USS Chesapeake, a 44-gun frigate, along with command of all gunboats at Norfolk.[118] The Chesapeake had just returned to Norfolk after repairs to damage incurred during the Chesapeake–Leopard Affair. Commodore Barron had just been relieved of command following his court martial over the incident. Decatur was a member of that court martial which had ruled Barron guilty of 'unpreparedness' barring him from command for five years. [119] Consequently Barron's previous orders to sail for the Mediterranean were canceled and the Chesapeake was instead assigned to Commodore Decatur with a squadron of gunboats to patrol the New England coast enforcing the Embargo Act throughout 1809. Unable to command Barron left the country for Copenhagen and remained there through the War of 1812. [120]

Before Decatur assumed command of the Chesapeake he learned from observers and then informed the Navy Secretary that the British ships Bellona and HMS Triumph were lightening their ballasts to prepare for a blockade at Norfolk.[121]

During this segment of his life Decatur's father, Stephen Decatur Sr., died in November of 1808 at the relatively young age of 57, with his mother's death following the next year. Both parents were laid to rest at St. Peter's Chruchyard in Philadelphia. [122]

Command of USS United States

In May of 1810 Decatur was appointed commander of the USS United States, a heavy frigate with 54 guns. This was the same vessel that he supervised the building of while employed at Gurney and Smith, and the same ship, then under the command of John Barry, on which he had commenced his naval career as Midshipman in 1798. The frigate had just been commissioned and was outfitted and supplied for service at sea. After taking command of the United States, now the rallying point of the young American Navy, Decatur sailed to most of the naval ports on the eastern seaboard and was well received at each stop. [123] [124] On May 21, 1811 he sailed the United States from Norfolk along with the USS Hornet on assignment to patrol the coast, returning to Norfolk on November 23 of that year. In 1812 he sailed with the Argus and the Congress but were soon recalled upon receiving news about the outbreak of war with Britain. There Decatur joined Captain John Rodgers commander of the President and his squadron. On this cruise Rodgers failed to accomplish his mission of intercepting the fleet of English West-Indiamen. On August 31, Decatur sailed the United States to Boston. On October 8 he sailed a second cruise with Rodgers' squadron. [125]

War of 1812

The desire for expansion into the Northwest Territory, the capture and impressment of American citizens into the Royal Navy along with British alliance with and recruitment of American Indian tribes against America were all events that led into the War of 1812.[126][127] Intended to avoid war, the Embargo Act only compounded matters that led to war. Finally on June 18, 1812, the United States declared war on Great Britain.[128] [129] By 1814 Britain had committed nearly 100 warships along the American coast and other points. Consequently the war was fought mostly in the naval theater where Decatur and other naval officers played major roles in the success of the United States efforts during this time.[130]

Upon the onset of the war President James Madison ordered several naval vessels to be dispatched to patrol the American coastline. The U.S. flagship, President, with 44 guns, the Essex, with 32, with the Hornet bearing 18 guns were joined in lower New York harbor by the United States with its 44 guns, commanded by Decatur, the Congress, bearing 38 guns, and the Argus with 16 guns. Secretary of State James Monroe [Note 4] had originally considered a plan that would simply use U.S. Naval vessels as mere barriers that would sit idle in various ports guarding their entrances. However through much protest and appeal from Naval officers the plan to confine America's naval vessels to port never materialized. [131]

Three days after the United States declared war against Britain a squadron under the command of Commodore John Rodgers in the President, along with Commodore Stephen Decatur of the United States, the Argus, Essex and the Hornet, departed from the harbor at New York City. [132] As soon as Rodgers received news of the declaration of war, fearing that the order to confine naval ships to port would be reconsidered by Congress, he and his squadron earnestly departed New York bay within the hour. The squadron patrolled the waters off the American upper east coast until the end of August, their first objective being a British fleet reported to have recently departed from the West Indies. [133]

United States captures Macedonian

Rodgers' squadron again sailed on October 8, 1812, this time from Boston, Massachusetts. Three days later, after capturing Mandarin, Decatur separated from Rodgers and his squadron and with the United States continued to cruise eastward. At dawn on October 25, five hundred miles south of the Azores, lookouts on board reported seeing a sail 12 miles to windward. As the ship slowly rose over the horizon, Captain Decatur made out the fine, familiar lines of HMS Macedonian, a British frigate bearing 38 guns. [134]

The Macedonian and the United States had been berthed next to one another in 1810, in port at Norfolk, Virginia. The British captain John Carden bet a fur beaver hat that if the two ever met in battle, the Macedonian would emerge victorious.[135] However, the engagement in a heavy swell proved otherwise as the United States pounded the [136] Macedonian into a dismasted wreck from long range. During the engagement Decatur was standing on a box of shot when he was knocked down almost unconscious when a flying splinter struck him in the chest. Wounded, he soon recovered and was on his feet in command again.[137] Because of the greater range of the guns aboard the United States Decatur and his crew got off seventy broadsides, with the Macedonian only getting off thirty, and consequently emerged from the battle relatively unscathed.[138] The Macedonian had no option but surrender, and thus was taken as a prize by Decatur. Eager to present the nation with a prize, Decatur and his crew spent two weeks repairing and refitting the captured British frigate to prepare it for its journey across the Atlantic to the United States.[139]

Blockade at New London

After undergoing routine repairs at New York the United States was part of a small squadron that included the newly captured and renamed USS Macedonian and the Sloop of War USS Hornet embarking on May 24, 1813. On June 1, the three vessels encountered a powerful British squadron on patrol and were forced to flee and take refuge at the port in New London, Connecticut and were kept blocked there until the end of the war.[140] [141]

Decatur attempted to sneak out of New London harbor at night in an effort to elude the British blockading squadron. On the evening of December 18 while attempting to leave the Thames River, Decatur saw blue lights burning near the mouth of the river in sight of the British blockaders. Convinced that these were signals to betray his plans he abandoned the project. In a letter to the Navy Secretary, dated December 20th, Decatur charged that traitors in the New London area were in collusion with the British to capture United States, the Hornet and the Macedonian. Whether the signals were given by an English spy or an American citizen is not certain. Republicans immediately blamed the Federalists who were adamantly against the war from the beginning, and so here earned themselves the name 'Blue-light Federalists'.[142]

Unable to get his squadron out of the harbor, Decatur decided to write a letter to Captain Thomas Hardy offering to negotiate a resolve of the situation at a prearranged meeting. He proposed that matched ships from either side meet and, in effect, have a duel, to settle their otherwise idle situation. The letter was sent under Flag of truce but was in violation of orders, as after the loss of the Chesepeake, Navy Secretary Jones forbade commanders from "... giving or receiving a Challenge, to or from, an Enemy's vessel.". The next day Hardy gave answer to Decatur's proposal and agreed to have Statira engage the Macedonian "...as they are sister ships, carrying the same number of guns, and weight of metal." After further deliberation Decatur wanted assurance that the Macedonian would not be recaptured should the ship emerge victorious, as he suspected it would be. After several communications it was ascertained that neither side could trust the other and so the proposal floundered, never coming to fruition.[143]

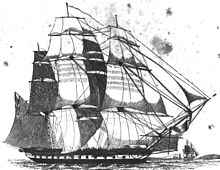

Command of the USS President

In May of 1814, Decatur transferred his commodore's pennant to the USS President, a frigate with 54 guns. [144] By December 1, 1814, Secretary of the Navy William Jones, a staunch proponent of coastal defense, appointed Decatur to lead a four-ship squadron comprising the USS President, which would be the flagship of his new squadron, along with the USS Hornet, a sloop bearing 20 guns, USS Peacock bearing 22 and the USS Tom Bowline bearing 12 guns. In January 1815, Decatur's squadron was assigned a mission in the East Indies, however, the British had established a strict blockade in the squadron's port of New York, therefore restricting any cruises. [145] On January 14th a severe snowstorm developed forcing the British squadron away from the coast, but by the next day the storm had subsided, allowing the British fleet to take up positions to the northwest in anticipation of the American fleet trying to escape. The next day the President emerged from the west [145] and Decatur attempted to break through the blockade alone in the President and make for the appointed rendezvous at Tristan da Cunha but encountered the British West Indies Squadron composed of Razee, HMS Majestic bearing 56 guns, under the command of Captain John Hayes, along with the frigates HMS Endymion, bearing 40 guns, commanded by Captain Henry Hope), HMS Pomone, bearing 38 guns, commanded by Captain John Richard Lumley) and HMS Tenedos, bearing 38 guns, commanded by Captain Hyde Parker. [146] Decatur had made arrangements for 'pilot boats' to mark the way for clear passage out to see, but due to a plotting error the pilot boats took up the wrong positions and consequently the President was accidentally run aground.[147]

After an hour and a half of twisting and hogging, with Decatur's ship procuring hull damage and a sprung mast, the ship finally broke free. Decatur continued the attempt to evade his pursuers and set course along the southerly coast of Long Island but with hull damage, lacked the speed and maneuverability to keep a safe distance from their pursuers. Endymion was the first to come up and after a fierce fight, Decatur managed to disable the British frigate, but receiving more damage to the President in the process.[148]

Due to the damage sustained, Decatur's frigate was finally overtaken by Pomone and Tenedos, causing him to surrender his command. However, his hail of surrender was not heard by Pomone, firing two broadsides into the President until she hauled down a light to signify surrender. As Decatur himself termed it, "...my ship crippled, and more than a four-fold force opposed to me, without a chance of escape left, I deemed it my duty to surrender". Decatur's command suffered 24 men killed and 55 wounded, a fifth of his crew, including Decatur himself who was wounded by a large flying splinter.[149] [147]

Soon the Majestic caught up with the British fleet now prevailing upon the President. Upon surrendering Decatur, now dressed in full dress uniform, boarded the Majestic and surrendered his sword to Captain Hayes. Hayes in a gesture of admiration returned the sword to Decatur saying that he was "...proud in returning the sword of an officer, who had defended his ship so nobly". Before taking possession of the President Hayes allowed Decatur to return to his ship to perform burial services for the officers and seamen who had died in the engagement. He was also allowed to write a letter to his wife. [150] Decatur along with surviving crew were taken prisoner and were help captive in a Bermuda prison, arriving January 26, and were held there until February 1815. Upon arrival at the prison in Bermuda the British naval officers extended various courtesies and provisions that they felt were due to a man of Decatur's stature. The senior naval officer at the prison took the earliest opportunity to parole Decatur to New London and on February 8, with news of the cessation of hostilities, Decatur traveled aboard New York City, where he convalesced in a boarding house.

At War's end Decatur received a sword as a reward and thanks from Congress for his service in Tripoli and was also awarded the Congressional Gold Medal for distinguished service in the War of 1812.[152]

See main Article: War of 1812 Second Barbary War

Now that war (of 1812) with Britain was over the United States could concentrate on pressing matters in the Mediterranean, at Algiers. As had occurred during the First Barbary War American merchant ships and crews were once again being seized and held for large ransoms. On February 23, 1815, President Madison urged Congress to declare war. Congress approved the act and on March 2, declared war against Algiers. Madison had chosen Benjamin Williams Crowninshield as the new Secretary of the Navy, replacing William Jones.[153]

Two squadrons were then assembled, one at New York, under the command of Stephen Decatur, one at Boston, under the command of Commodore William Bainbridge. Decatur's squadron of ten ships was ready first and set sail for Algiers on May 20. Decatur was in command of the flagship Guerriere. Aboard was William Shaler who had just been appointed by Madison as the counsul-general for the Barbary States, acting as joint commissioner with Commodores Decatur and Bainbridge. [154] Shaler was in possession of a letter authorizing them to negotiate terms of peace with the Algierian government. [155] Because of Decatur's great successes in the War of 1812 and for his knowledge of and past experience at the Algerian port, Crowninshield chose him to command the lead ship in the naval squadron to Algiers. [156]

The US was demanding the release of Americans held captive as slaves, an end of annual payments of tribute, and finally to procure favorable prize agreements. [157] Decatur was prepared to negotiate peace or resort to military measures. Eager to know the Dey's decision, Decatur dispatched the president's letter which ultimately prompted the Dey to abandon his practice of piracy and kidnapping and come to terms with the United States.[158] [159]

Command of USS Guerriere

On May 20, 1815, Commodore Decatur received instructions from President James Madison to take command of the frigate USS Guerriere and lead a squadron of ten ships to the Mediterranean Sea to conduct the Second Barbary War, which would put an end to the international practice of paying tribute to the Barbary pirate states. His squadron arrived at Gibraltar on June 14. [160]

Before committing himself to the Mediterranean Decatur learned from the American consuls at Cadiz and Tangier of any squadrons passing by along the Atlantic coast or through the straight of Gibraltar. To avoid making known the presence of an American squadron, Decatur did not enter the ports but instead dispatched a messenger in a small boat to communicate with the consuls. [161] He learned from observers there that a squadron under the command of the notorious Rais Hamidu had passed by into the Mediterranean, most likely off Cape de gat. Decatur's squadron arrived at Gibraltar on 15 June 1815. This attracted much attention and prompted the departure of several dispatch vessels to warn Hammida of the squadron's arrival. Decatur's visit was brief with the consul and lasted only for as long as it took to communicate with a short letter to the Secretary of the Navy informing him of earlier weather problems and that he was about to "proceed in search of the enemy forthwith", where he at once set off in search of Hammida hoping to take him by surprise. [162] [163]

On June 17 while sailing in the Gurriere for Algiers, Decatur's fleet encountered near Cape Palos the frigate Mashouda, commanded by Hammida and the Algerian brig Estedio, which were also en route to Algeria . After overtaking the Algerian ship Mashouda, Decatur fired two broadsides, crippling the ship, killing 30 of the crew, including Hammida himself, and taking more than 400 prisoners. [164]

Capturing the flagship of the Algerian fleet at the Battle off Cape Gata Decatur was able to secure sufficient levying power to bargain with the Dey of Algiers. Upon arrival, Decatur exhibited an early use of gunboat diplomacy on behalf of American interests as a reminder that this was the only alternative if the Dey decided to decline signing a treaty. Consequently a new treaty was agreed upon within 48 hours of Decatur's arrival, confirming the success of his objectives. [165]

After bringing the government in Algiers to terms, Decatur's squadron set sail to Tunis and Tripoli to demand reimbursement for proceeds withheld by those governments during the War of 1812. With a similar show of force exhibited at Algiers Decatur received all of his demands and promptly sailed home victorious. Upon his arrival Decatur boasted to the Secretary of the Navy that the settlement had "...been dictated at the mouths of our cannon." [166] [167] For this campaign, he became known as "the Conqueror of the Barbary Pirates".[168]

See main Article: Second Barbary War Domestic life

After his victory in the Mediterranean over the Barbary states who had terrorized and enslaved Christian merchants for centuries, Decatur returned to the United States, arriving at New York on November 12, 1815, with the brig Enterprise, along with Bainbridge of the Guerriere who arrived three days later'. He was met with a wide reception from dignitaries and countrymen. [169] Among the more notable salutations was a letter Decatur received from the Secretary of State James Monroe that related the following tidings of appreciation:

-

- "I take much interest in informing you that the result of this expedition, so glorious to your country and honorable to yourself and the officers and men under your command, has been very satisfactory to the President." - JM [170]

The Secretary of the Navy, Benjamin W. Crowninshield, was equally gracious and thankful. Since a vacancy was about to occur in the board of Navy commissioners with the retirement of Commodore Isaac Hull, the Secretary was most anxious to offer the position to Decatur, which he gladly accepted. Upon his appointment Decatur made his journey to Washington, where he was again received with cordial receptions from various dignitaries and countrymen. He served on the Board of Navy Commissioners from 1816 to 1820. One of his more notable decisions as a commissioner involved his strong objection to the reinstatement of James Barron upon his return to the United States after being barred from command for five years for his questionable handling of the Chesapeake, an action that would soon lead to Barron challenging him to a duel. [171] [172]

During his tenure as a Commissioner, Decatur also became active in the Washington social scene. At one of his social gatherings, Decatur uttered an after-dinner toast that would become famous: "Our Country! In her intercourse with foreign nations may she always be in the right; but right or wrong, our country!" [173][174] Carl Schurz would later distill this phrase more famously as, "My country, right or wrong; if right, to be kept right; and if wrong, to be set right." [175]

Home in Washington

Now that Decatur was Naval Commissioner he had settled into a routine life in Washington working at the Navy Department during the day with many evenings spent as an honorary guest at social gatherings as both he and his wife were the toast of Washington society. [176] In 1818, Decatur built a three story red brick house in Washington, DC, on the Lafayette Square, designed by the famous English architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe, considered the father of American Architecture, the same man who designed the U.S. Capital building and Saint John's Church. [177] Decatur specified that his house had to be suitable for "impressive entertainments". The house was the first private residence to be built near the White House. The Decatur House is now a museum that exhibits a large collection of Decatur memorabilia and is managed by the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Located on President's Square (Lafayette Square), in Washington, DC it was built in grand style to accommodate large social gatherings which in the wake of Decatur's many naval victories, were an almost routine affair in the lives of Decatur and his wife. [178]

Duel between Perry and Heath

In October of 1818 Decatur, having been asked by Oliver Hazard Perry, a very close friend, arrived at New York to act as his 'second' in a duel between Perry and Captain John Heath, the commander of the Marines on the USS Java. The two officers were involved in a personal disagreement while aboard that ship that resulted in Heath challenging Perry to a duel . Perry had written to Decatur nearly a year previous, revealing that he had no intention of firing any shot at Heath. After the two duelists and their seconds assembled the duel took place and after one shot was fired, Heath had missed his opponent, while Perry keeping his word, returned no fire. At this point Decatur approached Heath with Perry's letter in hand relating to Heath that Perry all along had no intention of returning fire. Asking Heath if his honor had thus been satisfied, Heath admitted that it had. Decatur was relieved to finally see the matter resolved with no lose of life or limb to either of his friends, urging both to now put the matter behind them. [179] [180] [181]

Untimely death

Decatur's life and distinguished service in the U.S. Navy came to an unfortunate end when in 1820, Commodore James Barron challenged Decatur to a duel, relating in part to comments Decatur had made over Barron's conduct in the Chesapeake-Leopard Affair of 1807. Because of Barron's loss of the Chesapeake to the British he faced a court martial and was barred from command for a term of five years. Decatur had served on the court-martial that had found Barron guilty of 'unpreparedness'. Barron had just returned to the United States from Copenhagen after being away for six years and was seeking reinstatement. [182] He was met with much criticism among fellow naval officers, among them Decatur was one of the most outspoken. Decatur, who was now on the board of naval commissioners, strongly opposed Barron's reinstatement and was notably critical about the prospect with other naval officers and government officials. As a result Barron became embittered towards Decatur and challenged him to a duel. [183] [184] Barron's challenge to Decatur occurred during a period when duels between officers were so common that it was creating a shortage of experienced officers forcing the War Department to threaten to discharge those who attempted to pursue the practice. [185]

Barron's second was Captain Jesse Elliott, known for his jaunty mannerism and antagonism to Decatur. Decatur had first asked his friend Thomas Macdonough to be his second, but Macdonough who had always opposed dueling accordingly declined his request.[186] Decatur then turned to his supposed friend Commodore William Bainbridge to act as his second, to which Bainbridge consented. However, Decatur made a poor choice: Bainbridge, who was five years his senior, had long been jealous of the younger and more famous Decatur. [187]

The seconds met on March 8th to establish the time, place and the rules of which the duel was to occur. The arrangements were exact. The duel was to take place at nine o'clock in the morning on March 22, at Bladensburg, Maryland near Washington -- and at a distance of only eight paces. Decatur, an expert pistol shot, planned only to wound Barron in the hip. [188]

Decatur did not tell his wife Susan about the forthcoming duel but instead wrote to her father asking that he come to Washington to stay with her, using language that suggested that he was facing a duel and that he might lose his life. [189] On the morning of the 22nd the dueling party assembled. The conference between the two seconds lasted three-quarters of an hour. [190] Just before the duel, Barron spoke to Decatur of conciliation; however, the men's seconds did not attempt to halt the proceedings. [191]

The duel was arranged by Bainbridge with Elliott in a way that made the wounding or death of both duelists very likely. Both subjects would be standing in close proximity of each other, face to face; There would be no back-to-back pacing away and turning to fire, a procedure that often resulted in the missing of one's opponent. Upon taking their places the duelists were instructed by Bainbridge, "I shall give the word quickly -- 'Present, one, two, three' -- You are neither to fire before the word 'one', nor after the word 'three'. Now in their positions, each duelist raised his pistol, cocked the flintlock and while taking aim stood in silence. Bainbridge called out, 'One', Decatur and Barron both firing before the count of 'two'. Decatur's shot hit Barron in the lower abdomen which ricocheted into his thigh. Barron's shot hit Decatur in the pelvic area, severing arteries. Both of the duelists fell almost at the same instant. Decatur, mortally wounded and clutching his side, exclaimed, "Oh, Lord, I am a dead man". Lying wounded Commodore Barron (who, ultimately survived) declared that the duel was carried out properly and honorably and told Decatur that he forgave him from the bottom of his heart. [192] [193]

By now other men who had known about the duel were arriving at the scene, including Decatur's friend and mentor, the senior office John Rodgers. Lying in excruciating pain, Decatur was carefully lifted by the surgeons and placed in Rodgers' carriage and was carried back to his home on Lafayette Square. Before they departed Decatur called out to Barron that he should also be taken along, but Rodgers and the surgeons calmly shook their heads in disapproval. Barron cried back "God bless you, Decatur" -- and with a weak voice Decatur called back "Farewell, farewell, Barron" Upon arrival at his home Decatur was taken in to the front room just left of the front entrance, still conscious. Before allowing himself to be carried in he insisted that his wife and nieces be taken upstairs, sparing them the sight of his grave condition. [194] A Dr. Thomas Simms arrived from his home nearby to give his assistance to the naval physicians, however, for reasons not entirely clear to historians, Decatur refused to have the ball extracted from his wound. [Note 5] At this point Decatur requested that his will be brought forward so as to receive his signature, granting his wife with all his worldly possessions, with directives as to whom would be the executors of his will. [196] Decatur died at approximately 10:30 p.m. that night. While wounded, he is said to have cried out, "I did not know that any man could suffer such pain!"[197]

Washington society and the nation were shocked upon learning that Decatur had been killed at the age of forty-one in a duel with a rival navy captain. Stephen Decatur's funeral was attended by Washington's elite, including President James Monroe and the justices of the Supreme Court, as well as most of Congress. Over 10,000 citizens of Washington and the surrounding area attended to pay their last respects to a national hero. The Marines led Decatur's funeral procession some of whom would soon be in the firing party, while its band played a mournful dirge. The pall bearers were Commodores Rodgers, Chauncey, Tingey, Porter and Macdonough and captains Ballard and Cassin and Lieutenant Macpherson. [198] Following along were Naval Officers and Seamen. At the funeral service a grieving seamen unexpectantly came forward and proclaimed, "He was the friend of the flag, the sailor's friend; the navy has lost its mainmast". [199] Stephen Decatur died childless. Though he left his widow $75,000, a fortune at the time, she died penniless in 1860.

Decatur's remains were temporarily placed in the tomb of Joel Barlow at Washington, but later moved to Philadelphia, where they were interred at St. Peter's Church, along side his mother and father.[200]

After the funeral rumors circulated of a last minute conversation between the duelists that could have avoided the deadly outcome of the duel, moreover, that the seconds involved might have been planning for such an outcome and accordingly made no real attempts to stop the duel. Decatur's wife Susan held an even more damning view of the matter and spent much of her remaining life pursing justice for what she termed "the assains" involved.[201]

Although he died at a relatively young age, Decatur helped in the direction the nation would go and played a significant role establishing the new nation’s identity.[202]

Legacy

The first USS Decatur, 1839 For his heroism in the Barbary Wars and the War of 1812 Decatur emerged as an icon of American Naval history and was roundly admired by most of his contemporaries as well as the citizenry.

- In honor to Stephen Decatur, five U.S. Navy ships have been named USS Decatur.

- At the urging of Franklin D. Roosevelt, the U.S. Post office Department issued a series of five stamps honoring the U.S. Navy and various naval heroes, Decatur being one of the few chosen, appearing on the 2-cent issue, along with fellow officer Macdonough.[203]

- An engraved portrait of Decatur appears on Stephen Decatur as depicted on a 1886 Silver Certificate on series 1886 $20 silver certificates.

- Stephen Decatur's home in Washington, D.C. is a museum owned by the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

- At least 46 communities in the United States have been named after Stephen Decatur

See also

- Naval History

- History of the United States Navy

- List of naval battles

- List of United States Navy people

- List of sailing frigates of the United States Navy

- Naval tactics in the Age of Sail

- Naval artillery in the Age of Sail

- Thomas Jefferson and the First Barbary War

- List of United States Navy ships

- List of Pirates

United States Navy portal Bibliography

- Mackenzie, Alexander Slidell (1846). Life of Stephen Decatur: a commodore in the Navy of the United States.

C. C. Little and J. Brown, 1846. pp. 443. Url

- Cooper, James Fenimore (1856). History of the Navy of the United States of America.

Stringer & Townsend, New York. pp. 508. OCLC 197401914. Url

- Waldo, Samuel Putnam (1821). The life and character of Stephen Decatur.

P. B. Goodsell, Hartford, Conn., 1821. pp. 312.

- Allison, Robert J. (2005). Stephen Decatur American Naval Hero, 1779–1820.

University of Massachusetts Press. pp. 253. ISBN 1-55849-492-8., Url

- Guttridge, Leonard F (2005). Our Country, Right Or Wrong: The Life of Stephen Decatur.

Tom Doherty Associates, LLC, New York, NY, 2006. pp. 304. ISBN 13:978-0-7653-0702-6.

- Allen, Gardner Weld (1905). Our Navy and the Barbary Corsairs.

Houghton Mifflin & Co., Boston, New York & Chicago. p. 354. -- url

- Allen, Gardner Weld (1909). Our naval war with France.

Houghton Mifflin & Co., Boston, New York and Chicago. p. 323. Url

- Leiner, Frederic C. (2007). The End of Barbary Terror, America's 1815 War against the Pirates of North Africa.

Oxford University Press, 2007. ISBN 9780195325409. -- Url

- Hickey, Donald R. (1989). The War of 1812, A Forgotten Conflict.

University of Illinois Press, Chicago and Urbana. ISBN 0-252-01613-0. url-1, url-2

- Hale, Edward Everett (1896). Illustrious Americans, Their Lives and Great Achievements.

International Publishing Company, Philadelphia, PA., and Chicago, ILL,

Entered 1896, by W. E. SCULL, in the office of the Librarian of Congress, Washington, DC. ISBN 9781162227023.

Illustrious Americans, Hale, 1896

- Tucker, Spencer (2004). Stephen Decatur: a life most bold and daring.

Naval Institute Press, 2004, Annapolis, Maryland. pp. 245. ISBN 1-55750-999-9. Url

- Whipple, Addison Beecher Colvin (2001). To the Shores of Tripoli:

the birth of the U.S. Navy and Marines.

Naval Institute Press, 2001. pp. 357. ISBN 10: 1-55750-966-2. Url

- Abbot, Willis John (1886). The Naval History of the United States.

Peter Fenelon Collier, New York. Url

- Lewis, Charles Lee (1924). Famous American Naval Officers.

L.C.Page & Company, Inc.. pp. 444. ISBN 0-8369-2170-4. Url

- Lewis, Charles Lee (1937). The Romantic Decatur.

Ayer Publishing, 1937. pp. 296. ISBN 0-8369-5898-5. Url

- Hill, Frederic Stanhope (1905). Twenty-six historic ships.

G.P. Putnam's Sons, New York and London. pp. 515. Url

- Macdonough, Rodney (1909). Life of Commodore Thomas Macdonough, U. S. Navy.

The Fort Hill press, Boston, Mass., 1909. pp. 303. Url

- Shaler, William; American Consul General at Algiers (1826). Sketches of Algiers.

Cummings, Hillard and Company, Boston, 1826. pp. 296. Url

- Canney, Donald L. (2001). Sailing warships of the US Navy.

Chatham Publishing / Naval Institute Press. pp. 224. ISBN 1-55750-990-5. Url

- Borneman, Walter R. (2004). 1812: the war that forged a nation.

Harper Colins, New York. pp. 349. ISBN 0-06-053112-6. Url

- Roosevelt, Theodore (1883). The naval war of 1812:.

G.P. Putnam's sons, New York. pp. 541. Url Url2

- Toll, Ian W. (2006). Six frigates: the epic history of the founding of the U.S. Navy.

W. W. Norton & Company, New York. pp. 592. ISBN 13:978-0-393-05847-5. Url

- Maclay, Edgar Stanton (1894). A history of the United States Navy, from 1775 to 1893.

D. Appleton & Company, New York. pp. 647. Url

- Hagan, Kenneth J. (1992). This People's Navy: The Making of American Sea Power.

The Free Press, New York. pp. 468. ISBN 0-02-913471-4. Url

- Bradford, James C. (1955). Quarterdeck and bridge: two centuries of American naval leaders.

Naval Institute Press, 1997. pp. 263. ISBN 1-55750-073-8. Url

- Hollis, Ira N. (1900). The frigate Constitution the central figure of the Navy under sail.

Houghton, Mifflin and Company, Boston and New York; The Riverside Press, Cambridge. pp. 455. Url

- Harris, Gardner W. (1837). The life and services of Commodore William Bainbridge, United States navy. New York:

Carey Lea & Blanchard. pp. 254. Url1 Url2

References

- ^ Waldo, 1821 Chapter I, Introductory

- ^ Mackenzie, 1846, pp.120-121

- ^ Allison, 2005 pp.1-17

- ^ Guttridge, 2005 p.226

- ^ "Commodore Stephen Decatur, USN, (1779-1820)".

Naval History & Heritage Command,

DEPARTMENT OF THE NAVY

. http://www.history.navy.mil/photos/pers-us/uspers-d/s-decatr.htm. Retrieved 4 June 2011. - ^ Guttridge, 2005 p.83

- ^ Waldo, 1821, pp.289-293

- ^ Mackenzie, 1846, pp.320-325

- ^ Waldo, 1821 p.13

- ^ Abbot, W. John, 1886 p.70

- ^ Waldo, 1821 pp.19-23

- ^ Waldo, 1821 p.40

- ^ Lewis, 1937 pp.5-6

- ^ a b Bradford, 1914 p.42

- ^ Mackenzie, 1846, pp.9-16

- ^ Tucker, 1937 p.39

- ^ Allison, 2005 pp.9-17

- ^ Lewis, 1937 p.7

- ^ Guttridge, 2005 p.26

- ^ MacKenzie, 1846 p.17

- ^ Tucker, 2004, pp.10-11

- ^ Lewis, 1937 p.7

- ^ Tucker, 1937 p.5

- ^ Allen, 1905 p.58

- ^ Tucker, 2004, pp.10-11

- ^ Mackenzie, 1846, p.25

- ^ Allison, 2005 p.17

- ^ MacKenzie, 1846 p.23

- ^ Lewis, 1924 p.42

- ^ Allen, 1909, p.42

- ^ Waldo, 1821 pp.30-31

- ^ Mackenzie, 1846, pp.21-25

- ^ a b Guttridge, 2005 p.30

- ^ Waldo, 1821 p.25

- ^ Lewis, 1937 p..191-192

- ^ Tucker, 1937 pp.19-20

- ^ MacKenzie, 1846 p.40

- ^ Lewis, 1937 pp.190-191

- ^ Lewis, 1937 pp.28-30

- ^ Lewis, 1937 p.30

- ^ Lewis, 1937 p.22

- ^ Lewis, 1937 p.20

- ^ Harris, 1837 pp.63-64

- ^ Guttridge, 2005 pp.45-46

- ^ Lewis, 1937 p.45

- ^ Tucker, 1937 p.27

- ^ Lewis, 1937 p.46

- ^ Mackenzie, 1846 pp.53-55

- ^ Mackenzie, 1846, p.47

- ^ MacKenzie, 1846 p.65

- ^ Lewis, 1937 p.32

- ^ Allen, 1905, p.160

- ^ Harris, 1837 pp.87-88

- ^ Lewis, 1937 p.43

- ^ Tucker, 1937p.45

- ^ Toll, 2006 p.209

- ^ Cooper, 1856 p.171

- ^ Tucker, 1937 p.40

- ^ Allen, 1905 p.169

- ^ MacKenzie, 1846 p.74

- ^ Lewis, 1937, p.44

- ^ MacKenzie, 1846 pp.331-335

- ^ MacKenzie, 1846 p.79

- ^ Mackenzie, 1846, p.68

- ^ Mackenzie, 1846, p.80

- ^ Tucker, 2004, p.57

- ^ Allen, 1905, p.281

- ^ Mackenzie, 1846, pp.64-80

- ^ Lewis, 1937 p.43

- ^ MacKenzie, 1846 p.122

- ^ MacKenzie, 1846 p.82

- ^ Guttridge, 2005 pp.68-70

- ^ Whipple, 2001 p.150

- ^ MacKenzie, 1846 p.88

- ^ Whipple, 2001, pp.150-154

- ^ Abbot, W. John, 1886 pp.203-204

- ^ Lewis, 1937, pp.69-70

- ^ MacKenzie, 1846 p.110

- ^ Waldo, 1821 p.120

- ^ Harris, 1837 p.108

- ^ Lewis, 1937 p.63

- ^ MacKenzie, 1846 p.91

- ^ Abbot, W. John, 1886 p.205

- ^ Lewis, 1924 p.49

- ^ Lewis, 1924 p.66

- ^ Allen, 1909, p.191

- ^ Lewis, 1937 p.272

- ^ Allen, 1905, p.192

- ^ Lewis, 1937 p.64

- ^ Toll, 2006 p.235

- ^ Lewis, 1937, pp.66-69

- ^ Guttridge, 2005 p.75

- ^ Bradford, 1914 p.45

- ^ Hollis, 1900 p.116

- ^ Leiner, 2007 p.42

- ^ Lewis, 1937, pp.50-51

- ^ MacKenzie, 1846, pp.120-121

- ^ MacKenzie, 1846 pp.119-120

- ^ Hollis, 1900 p.116-177

- ^ Waldo, 1821 p.155

- ^ MacKenzie, 1846 pp.132-134

- ^ Mackenzie, 1846, p.144

- ^ Guttridge, 2005 pp.83-84

- ^ Lewis, 1937 p.89

- ^ Tucker, 1937 p.174

- ^ Tucker, 1937 p.11

- ^ Lewis, 1937 p.89

- ^ Leiner, 2007 p.26

- ^ Mackenzie, 1846 pp.145

- ^ Cooper, 1856 p.224

- ^ Cooper, 1856 p.228

- ^ Borneman, 2004 p.23

- ^ MacKenzie, 1846 pp.146-147

- ^ Tucker, 1937 p.88

- ^ Borneman, 2004 pp.19-22

- ^ Toll, 2006 p.470

- ^ MacKenzie, 1846 p.141

- ^ Mackenzie, 1846 p.151

- ^ MacKenzie, 1846 p.149

- ^ Guttridge, 2005 pp.217-219

- ^ Guttridge, 2005 p.101

- ^ Mackenzie, 1846 pp.151-152

- ^ Waldo, 1821 pp.163-166

- ^ Hill, 1905 p.201

- ^ Hill, 1905 p.202

- ^ Hale, 1896, pp.144-149

- ^ Tucker, 1937, pp.105-106

- ^ Guttridge, 2005 p.129

- ^ Waldo, 1821 p.170

- ^ Maclay, 1894 p.1

- ^ Hickey, 1989 p.92

- ^ Roosevelt, 1883 pp.72-73

- ^ Abbot, W. John, 1886 p.291

- ^ Heidler, 2004 p.149

- ^ Abbot, W. John, 1886 p.324

- ^ Tucker, 1937 p.11

- ^ Maclay, 1894 p.68

- ^ Hickey, 1989 p.94

- ^ Canney, 2001 p.60

- ^ Waldo, 1821, p.224

- ^ Cooper, 1856 p.11

- ^ Hickey, 1989 pp.257-259

- ^ Toll, 2006 p.425

- ^ Tucker, 1937 p.144

- ^ a b Roosevelt, 1883 p.401

- ^ Maclay, 1894 p.71

- ^ a b Roosevelt, 1883 pp.401-405

- ^ Roosevelt, 1883 p.402

- ^ Hickey, 1989, p.216

- ^ MacKenzie, 1846 pp.226-228

- ^ MacKenzie, 1846 pp.231-232

- ^ "Captain Stephen Decatur".

DEPARTMENT OF THE NAVY -- NAVAL HISTORICAL CENTER. http://www.history.navy.mil/bios/decatur.htm. Retrieved 2 June 2011. - ^ Leiner, 2007 p.40

- ^ Harris, 1938 pp.198-199

- ^ Allen, 1905, p.281

- ^ Leiner, 2007 pp.39-41

- ^ Mackenzie, 1846, pp.244-245

- ^ Cooper, 1856 p.443

- ^ Cooper, 1856 pp.442-443

- ^ Waldo, 1821 p.248

- ^ Maclay, 1894 pp.90-91

- ^ Allen, 1905 pp.281-282

- ^ Leiner, 2007 pp.92-93

- ^ Waldo, 1821 p.248

- ^ Waldo, 1821 p.250

- ^ Hagan, 1992 p.92

- ^ Guttridge, 2005 p.190

- ^ U.S. Naval Institute

- ^ Tucker, 2004 p.168

- ^ MacKenzie, 1846 p.291

- ^ Mackenzie, 1846, p.291

- ^ Waldo, 1821 p.286

- ^ Mackenzie, 1846, p.295

- ^ Guttridge, 2005 Review, back cover

- ^ Allison, 2005 prologue, pp.2-3

- ^ Tucker, 1937 p.174

- ^ "Decatur House on Lafayette Square".

THE WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION

. http://www.whitehousehistory.org/decatur-house/history_decatur-house.html. Retrieved 30 July 2011. - ^ Tucker, 1937 p.174

- ^ Lewis, 1937 p.198

- ^ MacKenzie, 1846 p.304

- ^ Tucker, 1937 p.175

- ^ Guttridge, 2005 p.217

- ^ Toll, 2006 p.470

- ^ Lewis, 1937 p.94

- ^ Hickey, 1989, p.222

- ^ Tucker, 1937 p.180

- ^ Mackenzie, 1846, p.316

- ^ Tucker, 2004 p.179

- ^ Tucker, 1937 p.179

- ^ Guttridge, 2005 pp.257-260

- ^ Mackenzie, 1846, p.440

- ^ Guttridge, 2005 pp.257-261

- ^ Mackenzie, 1846, p.441

- ^ Allison, 2005 p.214

- ^ Guttridge, 2005 p.262

- ^ Guttridge, 2005 p.262

- ^ Mackenzie, 1846, p.3

- ^ Rodney MacDonough, 1909 p.243

- ^ Mackenzie, 1846, pp.331-335

- ^ Mackenzie, 1846, p.442

- ^ Guttridge, 2005 pp.268-269

- ^ Allison, 2005 pp.1-10

Notes

- ^ Some sources spell the name as 'Siren' . [54]

- ^ Some sources claim the man could have been Ruben James. [87] [88]

- ^ Striking colors, i.e.Lowering the ship's flag, was an international signal of surrender.

- ^ Monroe was later appointed Secretary of War in September 1814.

- ^ Among the current sources only Guttridge mentions Decatur's refusal to have the ball extracted, not citing any reason. [195]

Further reading

- De Kay, James Tertius. A Rage for Glory: The Life of Commodore Stephen Decatur, USN. Free Press, 2004. ISBN 0-7432-4245-9.

- London, Joshua E. Victory in Tripoli: How America's War with the Barbary Pirates Established the U.S. Navy and Shaped a Nation. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2005. ISBN 0-471-44415-4

- Oren, Michael B. Power, Faith, and Fantasy: America in the Middle East, 1776 to the Present. New York: W.W. Norton, 2007 ISBN 0-393-05826-3

- Miller, Nathan. The US Navy: An Illustrated History (New York: American Heritage, 1977)

- Lowe, Corinne. Knight of the Sea: The Story of Stephen Decatur. Harcourt, Brace. 1941. 286pp.

- Lardas, Mark. Decatur's Bold and Daring Act, The Philadelphia in Tripoli 1804; Osprey Raid Series #22; Osprey Publishing (2011). ISBN 978-1-84908-374-4

External links

- Naval History Bibliography

DEPARTMENT OF THE NAVY -- NAVAL HISTORICAL CENTER - Commodore Stephen Decatur, USN, (1779-1820),

DEPARTMENT OF THE NAVY -- Naval Historical Center - Stephen Decatur grave site

- Biography of Decatur from the Naval Historical Center, Washington, D.C.

- The Stephen Decatur House Museum: Washington, DC

- Decatur House: A Home of the Rich and Powerful, a National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) lesson plan

- Correspondence, between the late Commodore Stephen Decatur and Commodore James Barron which led to the unfortunate meeting of the twenty-second of March

- "Stephen Decatur". Find a Grave. http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=269. Retrieved 2008-03-31.

- Reference map of former Barbary States (Morocco, Algeria, Tunis and Libya)

- DOCUMENTS, OFFICIAL AND UNOFFICIAL, RELATING TO THE CASE OF THE CAPTURE AND DESTRUCTION OF THE FRIGATE PHILADELPHIA, AT TRIPOLI

Categories:- 1779 births