- Confederate States of America

-

This article is about the historical state. For the 2004 mockumentary, see C.S.A.: The Confederate States of America.

Confederate States of America Unrecognized state[1][2] ↓ 1861–1865  →

→

Flag Great Seal Motto

Deo Vindice (Latin)

"Under God, our Vindicator"Anthem

(none official)

"God Save the South" (unofficial)

"The Bonnie Blue Flag" (popular)

"Dixie" (traditional)Capital Montgomery, Alabama

(until May 29, 1861)

Richmond, Virginia

(May 29, 1861 – April 3, 1865)

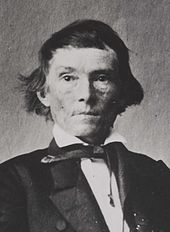

Danville, Virginia

(after April 3, 1865)Language(s) English (de facto) Government Confederal Republic President - 1861–1865 Jefferson Davis Vice President - 1861–1865 Alexander Stephens Legislature Congress - Upper house Senate - Lower house House of Representatives Historical era American Civil War - Confederacy formed February 4, 1861 - Constitution created March 11, 1861 - Battle of Fort Sumter April 12, 1861 - Siege of Vicksburg May 18, 1863 - Military collapse April 9, 1865 - Confederacy dissolved May 5, 1865 Area - 18601 1,995,392 km2 (770,425 sq mi) Population - 18601 est. 9,103,332 Density 4.6 /km2 (11.8 /sq mi) - slaves2 est. 3,521,110 Currency Confederate dollar

State CurrenciesPreceded by Succeeded by

United States

Republic of South Carolina

Republic of Mississippi

Republic of Florida

Alabama Republic

Republic of Georgia

Republic of Louisiana

Republic of Texas United States

1 Area and population values do not include Missouri and Kentucky nor the Confederate Territory of Arizona. Water area: 5.7%.

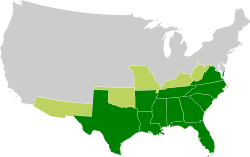

2 Slaves included in above population count 1860 CensusThe Confederate States of America (also called the Confederacy, the Confederate States, C.S.A. and The South) was a government set up from 1861 to 1865 by 11 Southern slave states of the United States of America that had declared their secession from the U.S. Secessionists argued that the United States Constitution was a compact among states which each state could abandon without consultation, each state having a right to secede. The U.S. government (The Union) rejected secession as illegal. Waiting until after its army was fired upon on April 12-13, 1861 at the Battle of Fort Sumter, the U.S. used military action to defeat the Confederacy. No foreign nation officially recognized the Confederate States of America as an independent country,[1][2] but they did allow their citizens to do business with the Confederacy.

With the attack on Fort Sumter, Lincoln called for 75,000 troops to recapture lost federal properties in the South, the same number of arms the disunionists confiscated from US forts and arsenals in six seceding states prior to his inauguration.[3] With the developing Federal policy of military action to suppress the rebellion, Arkansas, Tennessee, North Carolina, and Virginia also declared their secession and joined the Confederacy. All the main tribes of the Indian Territory (later Oklahoma) aligned with the Confederacy, but efforts to secure secession in Missouri, Kentucky, and Maryland failed in the face of federal military action and occupation of those states.

The Confederate government in Richmond had an uneasy relationship with its member states, with some historians arguing the Confederacy "died of states' rights" because of the reluctance of several states to put troops under the control of the Confederate States government.[4] Control over its claimed territory shrank steadily during the course of the American Civil War, as the Union secured of much of the seacoast and inland waterways. During four years of bloody campaigning, the leading Confederate General Robert E. Lee repelled all Union attempts to capture the Confederate capital at Richmond, Virginia, but the Confederates faced an insurmountable disadvantage in terms of men, supplies and public support.

The Confederacy effectively collapsed after Ulysses S. Grant captured Richmond, Virginia and Lee's army in April 1865. Congress was not sure that white Southerners had really given up slavery or their dreams of Confederate nationalism, so it began a decade-long process known as Reconstruction. It sent the Thirteenth Amendment to free slaves out to the states before Lincoln's assassination, expelled ex-Confederate leaders from office with Congressional Reconstruction, enacted civil rights and voting rights legislation, and imposed conditions on the readmission of the state delegations to Congress. The war left the South economically devastated by military action and by the practice of using up resources to fight the war. The region remained well below national levels of prosperity until after World War II.[5]

Contents

History

A “Revolution” in disunion

Main article: Origins of the American Civil WarThe Confederate States of America was created by secessionists in Southern slave states who refused to accept the results of the presidential election of 1860, in which the newly-formed, anti-slavery Republican Party won its first election. The secessionists, who mostly belonged to the Southern faction of the Democratic Party, had been talking of secession for years prior to 1860. They believed the South to be under attack by abolitionists and anti-slavery elements in the Republican Party. Southern interests in the United States had been protected by doughface presidents and congressmen, northern politicians with southern principles and patronage. The Supreme Court had been led by slaveholders, and its rulings had been favorable to its perpetuation. Nevertheless, during the campaign for president in 1860, secessionists threatened disunion at Lincoln’s election, most notably by William L. Yancey. However there were no plans underway to set up a new country.[6]

With election, Lincoln explained that as president he could be voted out in four years. All since Andrew Jackson had been. He would have little direct power over the South except for the appointment of local postmasters. But Secessionists warned that Republican postmasters would resume allowing the mail to carry newspapers or pamphlets advocating freedom for all Americans, meaning freedom for slaves. They pointed out so had John Brown, who had tried to foster widespread slave insurrection.[6]The arguments of the disunionists emphasized states rights and warned against a strong national government—themes that came to haunt the Confederacy, with some historians arguing that it "died of states rights."

Causes of secession

Historian Emory Thomas reconstructed the Confederacy's self image by studying the correspondence sent by the Confederate government in 1861–62 to foreign governments. He found that the C.S.A. had multiple self images:

The Southern nation was by turns a guileless people attacked by a voracious neighbor, an 'established' nation in some temporary difficulty, a collection of bucolic aristocrats making a romantic stand against the banalities of industrial democracy, a cabal of commercial farmers seeking to make a pawn of King Cotton, an apotheosis of nineteenth-century nationalism and revolutionary liberalism, or the ultimate statement of social and economic reaction."[7]By 1860, sectional disagreements between North and South revolved primarily around the maintenance or expansion of slavery. Historian Drew Gilpin Faust observed that "leaders of the secession movement across the South cited slavery as the most compelling reason for southern independence."[8] Although this may seem strange, given that the majority of white Southerners did not own slaves, virtually every single white Southerner supported slavery because they did not want to be at the bottom of the social ladder.[9] Related and intertwined secondary issues also fueled the dispute; these secondary differences included issues of free speech, runaway slaves, expansion into Cuba, and states' rights. The immediate spark for secession came from the victory of the Republican Party and the election of Abraham Lincoln in the 1860 elections. Civil War historian James M. McPherson wrote:

To southerners the election’s most ominous feature was the magnitude of Republican victory north of the 41st parallel. Lincoln won more than 60 percent of the vote in that region, losing scarcely two dozen counties. Three-quarters of the Republican congressmen and senators in the next Congress would represent this "Yankee" and antislavery portion of the free states. The New Orleans Crescent saw these facts as "full of portentous significance". "The idle canvas prattle about Northern conservatism may now be dismissed," agreed the Richmond Examiner. "A party founded on the single sentiment... of hatred of African slavery, is now the controlling power." No one could any longer "be deluded... that the Black Republican party is a moderate" party, pronounced the New Orleans Delta. "It is in fact, essentially, a revolutionary party."[10]In what later became known as the Cornerstone Speech, C.S. Vice President Alexander Stephens declared that the "cornerstone" of the new government "rest[ed] upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery—subordination to the superior race—is his natural and normal condition. This, our new government, is the first, in the history of the world, based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth".[11] In later years, however, Stephens made efforts to qualify his remarks, claiming they were extemporaneous, metaphorical, and never meant to literally reflect "the principles of the new Government on this subject."[12][13]

Four of the seceding states, the Deep South states of South Carolina,[14] Mississippi,[15] Georgia,[16] and Texas,[17] issued formal declarations of causes, each of which identified the threat to slaveholders’ rights as the cause of, or a major cause of, secession. Georgia also claimed a general Federal policy of favoring Northern over Southern economic interests. Texas mentioned slavery 21 times, but also listed the failure of the federal government to live up to its obligations, in the original annexation agreement, to protect settlers along the exposed western frontier.

Texas further stated:

We hold as undeniable truths that the governments of the various States, and of the confederacy itself, were established exclusively by the white race, for themselves and their posterity; that the African race had no agency in their establishment; that they were rightfully held and regarded as an inferior and dependent race, and in that condition only could their existence in this country be rendered beneficial or tolerable.And again:

That in this free government all white men are and of right ought to be entitled to equal civil and political rights [emphasis in the original]; that the servitude of the African race, as existing in these States, is mutually beneficial to both bond and free, and is abundantly authorized and justified by the experience of mankind, and the revealed will of the Almighty Creator, as recognized by all Christian nations; while the destruction of the existing relations between the two races, as advocated by our sectional enemies, would bring inevitable calamities upon both and desolation upon the fifteen slave-holding states.[17]Secessionists and conventions

The Fire-Eaters, calling for immediate secession, were opposed by two elements. "Cooperationists" in the Deep South would delay secession until several states went together, maybe in a Southern Convention. Under the influence of men such as Texas Governor Sam Houston, delay had the effect of sustaining the Union.[18] "Unionists", especially in the Border South, often former Whigs, appealed to sentimental attachment to the United States. Their favorite was John Bell of Tennessee.

-

William Yancy, AL Fire-eater

”The Orator of Secession” -

William Henry Gist, SC Gov.

called Secessionist Convention

Secessionists were active politically. Governor William Henry Gist of South Carolina corresponded secretly with other Deep South governors, and most governors exchanged clandestine commissioners.[19] Charleston’s 1860 Association published over 200,000 pamphlets to persuade the youth of the South. The top three were South Carolina’s John Townsend’s “The Doom of Slavery”, “The South Alone Should Govern the South”, and James D.B. De Bow’s “The Interest of Slavery of the Southern Non-slaveholder.[20]

Developments in South Carolina started a chain of events. The foreman of a jury refused the legitimacy of federal courts, so Federal Judge Andrew Magrath ruled that U.S. judicial authority in South Carolina was vacated. A mass meeting in Charleston celebrating the Charleston and Savannah railroad and state cooperation led to the South Carolina legislature to call for a Secession Convention. U.S. Senator James Chesnut, Jr. resigned, and U.S. Senator James Henry Hammond followed.[21]

Elections for Secessionist conventions were heated to “an almost raving pitch, no one dared dissent” Even once respected voices, including the Chief Justice of South Carolina, John Belton O’Neall, lost election to the Secession Convention on a Cooperationist ticket. Across the South mobs lynched Yankees and (in Texas) Germans suspected of loyalty to the United States.[22] Generally, seceding conventions which followed did not call for a referendum to ratify, although Texas, Arkansas, and Tennessee did, also Virginia’s second convention. Missouri and Kentucky declared neutrality.

Inauguration and response

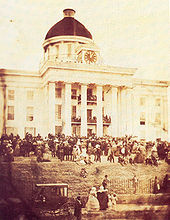

The first secession state conventions from the Deep South sent representatives to meet at the Montgomery Convention in Montgomery, Alabama on February 4, 1861. There the fundamental documents of government were promulgated, a provisional government was established, and a representative Congress met for the Confederate States of America.[23]

The new Confederate President Jefferson Davis, a former "Cooperationist" who had insisted on delaying secession until a united South could move together, issued a call for 100,000 states' militia to defend the new-born nation.[23] Previously John B. Floyd, U.S. Secretary of War under President James Buchanan, had moved arms south out of northern U.S. armories. To economize War Department expenditures, Floyd and Congressional elements persuaded Buchanan not to put the armaments for southern forts into place. These were now appropriated to the Confederacy along with bullion and coining dies at the U.S. mints in Charlotte, North Carolina; Dahlonega, Georgia; and New Orleans.[23]

In his first Inaugural Address, Abraham Lincoln tried to contain the expansion of the Confederacy. To quiet the rising calls for session in additional slave-holding states, he assured the Border States that slavery would be preserved in the states where it existed, and he entertained a proposed Thirteenth "Corwin Amendment" under consideration to explicitly protect slavery in the Constitution.[24]

The newly inaugurated Confederate Administration pursued a policy of national territorial integrity, continuing earlier state efforts in 1860 and early 1861 to remove U.S. government presence from within their boundaries. These efforts included taking possession of U.S. courts, custom houses, post offices, and most notably, arsenals and forts. But at the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter, Lincoln called up 75,000 of the states’ militia to muster under his command. The stated purpose was to re-occupy U.S. properties throughout the South, as the U.S. Congress had not authorized their abandonment. The resistance at Fort Sumter signaled his change of policy from that of the Buchanan Administration. Lincoln's response ignited a firestorm of emotion. The people both North and South demanded war, and young men rushed to their colors. Four more states (Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Arkansas) declared secessions, while Kentucky tried to remain neutral.[23]

Secession

Secessionists argued that the United States Constitution was a compact among states that could be abandoned at any time without consultation and that each state had a right to secede. After intense debates and statewide votes, seven Deep South cotton states passed secession ordinances by February 1861 (before Abraham Lincoln took office as president), while secession efforts failed in the other eight slave states.

Delegates from the seven formed the C.S.A. in February 1861, selecting Jefferson Davis as temporary president until elections could be held in 1862. Talk of reunion and compromise went nowhere, because the Confederates insisted on independence which the Union strongly rejected. Davis began raising a 100,000 man army.[25]

States

Seven states declared their secession from the United States before Lincoln took office on March 4, 1861:

1. South Carolina (December 20, 1860)[26][27]

2. Mississippi (January 9, 1861)[28]

3. Florida (January 10, 1861)[29]

4. Alabama (January 11, 1861)[30]5. Georgia (January 19, 1861)[31]

6. Louisiana (January 26, 1861)[32]

7. Texas (February 1, 1861)[33]After the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter April 12, 1861, and Lincoln's subsequent call for troops on April 15, four more states declared their secession:[34]

8. Virginia (April 17, 1861; referendum May 23, 1861)[35]

9. Arkansas (May 6, 1861)[36]10. Tennessee (May 7, 1861; referendum June 8, 1861)[37][38]

11. North Carolina (May 20, 1861)[39]Confederate States

in the

American Civil WarSouth Carolina

Mississippi

Florida

Alabama

Georgia

Louisiana

Texas

Virginia

Arkansas

North Carolina

TennesseeDual governments Border states Delaware

Maryland

West VirginiaTerritories Kentucky declared neutrality but after Confederate troops moved in it asked for Union troops to drive them out. Confederates tried to set up their own state government, but it was driven out and never controlled Kentucky. The Union had a rump government in Virginia, and when its western counties rejected the Confederacy the Unionists government approved the creation of West Virginia, which was admitted to the U.S. as a state.

In Missouri, a pro-CSA remnant of the General Assembly met on October 31, 1861, and although lacking a quorum in either house, passed an ordinance of secession.[40][41] However, this occurred after a standing constitutional convention declared the legislature and governor void after Federal troops marched on and took over the capital. The Confederate government was driven out of Missouri and never was in control of the state. Missouri never seceded and was not covered by the Emancipation Proclamation. The standing State constitutional convention repealed slavery in Missouri before Federal constitutional amendments passed.

The Confederacy recognized the pro-Confederate claimants in both Kentucky and Missouri and laid claim to those states based on their authority, with representatives from both states seated in the Confederate Congress. Later versions of Confederate flags had 13 stars, reflecting the Confederacy's claims to Kentucky and Missouri, and the large numbers of soldiers they provided.

On April 27, 1861, President Lincoln, in response to the destruction of railroad bridges and telegraph lines by southern sympathizers in Maryland (surrounding Washington, D.C., on three sides), authorized General Scott to suspend the writ of habeas corpus along the railroad line from Philadelphia to Baltimore to Washington.[42]

Delaware, also a slave state, never considered secession, nor did Washington, D.C. Although the slave states of Maryland and Delaware did not secede, citizens from those states did exhibit divided loyalties. Only Delaware among the slave states did not produce a full regiment to fight for the Confederacy. Delaware achieved the distinction of providing more soldiers by percentage than any other state, and overwhelmingly they fought for the Union.

In 1861, a Unionist legislature in Wheeling, Virginia, seceded from Virginia, eventually claiming 50 counties for a new state. However, 24 of those counties had voted in favor of Virginia's secession, and control of these counties, as well as some counties that had voted against secession, remained contested until the end of the war.[43] West Virginia joined the United States in 1863 with a constitution that gradually abolished slavery. According to military historian Russell F. Weigley, "Most of West Virginia went through the Civil War not as an asset to the Union but as a troublesome battleground..."[44]

Confederate declarations of martial law checked attempts to secede from the Confederate States of America by some counties in East Tennessee.[45][46]

Territories

Main articles: Confederate Arizona, New Mexico Territory in the American Civil War, and Indian Territory in the American Civil WarCitizens at Mesilla and Tucson in the southern part of New Mexico Territory (modern day New Mexico and Arizona) formed a secession convention, which voted to join the Confederacy on March 16, 1861, and appointed Lewis Owings as the new territorial governor.

Elias C. Boudinot

Elias C. Boudinot

Arkansas secessionist leader

LtCol. under Stand Watie

represented Cherokee OK Terr.In July, the Mesilla government appealed to Confederate troops in El Paso, Texas, under Lieutenant Colonel John Baylor for help in removing the Union Army under Major Isaac Lynde that had taken up position nearby. The Confederates defeated Lynde's forces at the Battle of Mesilla on July 27, 1861. After the battle, Baylor established a territorial government for the Confederate Arizona Territory and named himself governor. The Confederacy proclaimed the portion of the New Mexico Territory south of the 34th parallel as the Confederate Arizona Territory on February 14, 1862,[47] with Mesilla serving as the territorial capital.[48]

In 1862 the Confederate General Henry Hopkins Sibley led a New Mexico Campaign to take the northern half of New Mexico. Although Confederates briefly occupied the territorial capital of Santa Fe, they suffered defeat at Glorieta Pass in March and retreated, never to return. The Union regained military control of the area, and on February 24, 1863, set up the U.S. Arizona Territory with Fort Whipple as the capital.

Confederate supporters also claimed portions of modern-day Oklahoma as Confederate territory after the Union abandoned and evacuated the federal forts and installations in the territory. The five tribal governments of the Indian Territory – which became Oklahoma in 1907 – mainly supported the Confederacy, providing troops and one general officer. On July 12, 1861, the newly formed Confederate States government signed a treaty with both the Choctaw and Chickasaw Indian nations in the Indian Territory.[49][50] After 1863 the tribal governments sent representatives to the Confederate Congress: Elias Cornelius Boudinot representing the Cherokee and Samuel Benton Callahan representing the Seminole and Creek people. The Cherokee, in their declaration of causes, gave as reasons for aligning with the Confederacy the similar institutions and interests of the Cherokee Nation and the Southern states, alleged violations of the Constitution by the North, claimed that the North waged war against Southern commercial and political freedom and for the abolition of slavery in general and in the Indian Territory in particular, and that the North intended to seize Indian lands as had happened in the past.[51]

Capitals

Montgomery, Alabama served as the capital of the Confederate States of America from February 4 until May 29, 1861. The naming of Richmond, Virginia as the new capital took place on May 30, 1861.

Shortly before the end of the war, the Confederate government evacuated Richmond, planning to relocate farther south. Little came of these plans before Lee's surrender at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865. Danville, Virginia, served as the last capital of the Confederate States of America, from April 3 to April 10, 1865.

Diplomacy

United States, a foreign power

During the four years of its existence, the Confederate States of America asserted its independence and appointed dozens of diplomatic agents abroad. The United States government, by contrast, regarded the Southern states as states in rebellion and refused any formal recognition of their status. Thus, even before the Battle of Fort Sumter, U.S. Secretary of State William H. Seward issued formal instructions in April 1861 to Charles Francis Adams, the newly appointed minister to Great Britain:

You will indulge in no expressions of harshness or disrespect, or even impatience concerning the seceding States, their agents, or their people. But you will, on the contrary, all the while remember that those States are now, as they always heretofore have been, and, notwithstanding their temporary self-delusion, they must always continue to be, equal and honored members of this Federal Union, and that their citizens throughout all political misunderstandings and alienations, still are and always must be our kindred and countrymen.[52]However, if the British seemed inclined to recognize the Confederacy, or even waver in that regard, they would receive a sharp warning, with a strong hint of war:

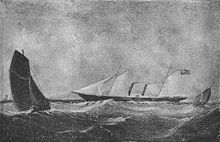

British Mail Packet, an ocean-going side-wheeler like the RMS Trent which caused a diplomatic crisis for the United States and Britain when Confederate diplomats were seized[53] [if Britain is] tolerating the application of the so-called seceding States, or wavering about it, you will not leave them to suppose for a moment that they can grant that application and remain friends with the United States. You may even assure them promptly, in that case, that if they determine to recognize, they may at the same time prepare to enter into alliance with the enemies of this republic.[52]

[if Britain is] tolerating the application of the so-called seceding States, or wavering about it, you will not leave them to suppose for a moment that they can grant that application and remain friends with the United States. You may even assure them promptly, in that case, that if they determine to recognize, they may at the same time prepare to enter into alliance with the enemies of this republic.[52]The Union government never declared war, but conducted its military efforts under a presidential proclamation issued April 15, 1861, calling for troops to recapture forts and suppress a rebellion.[54][55] Mid-war negotiations between the two sides occurred without formal political recognition, though the laws of war governed military relationships.

Following the Battle of Fort Sumter, the Confederate Congress asserted on May 6, 1861:

... war exists between the Confederate States and the Government of the United States, and the States and Territories thereof, excepting the States of Maryland, North Carolina, Tennessee, Kentucky, Arkansas, Missouri, and Delaware, and the Territories of Arizona, and New Mexico, and the Indian Territory south of Kansas...[56]Four years after the war, in 1869, the United States Supreme Court in Texas v. White ruled Texas' declaration of secession was legally null and void. The court's opinion was authored by Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase. The court did allow some possibility of separation from the Union "through revolution or through consent of the States."[57][58]

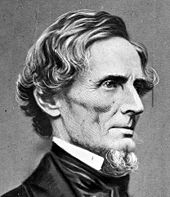

Jefferson Davis, former President of the Confederacy, and Alexander Stephens, its former Vice-President, both penned arguments in favor of secession's legality, most notably Davis' The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government.

International diplomacy

Once the war with the United States began, the Confederacy pinned its hopes for survival on military intervention by Britain and France. The United States realized this as well and made it clear that diplomatic recognition of the Confederacy meant war with the United States – and the cutting off of food shipments into Britain. The Confederates who had believed that "cotton is king" – that is, Britain had to support the Confederacy to obtain cotton – proved mistaken. The British had ample stocks to last over a year, and had been developing alternative sources of cotton (most notably India and Egypt) and were not about to go to war with the U.S. to try to get more cotton.[59][60]

The Confederate government sent repeated delegations to Europe; historians give them low marks for their poor diplomacy.[61] James M. Mason went to London and John Slidell traveled to Paris, but neither was officially received. Each did succeed in holding unofficial private meetings with high British and French officials but neither secured official recognition for the Confederacy. Britain and the United States came dangerously close to war during the Trent Affair (when the U.S. Navy seized two Confederate agents traveling on a British ship in late 1861), and it seemed possible that the Confederacy would see its much desired recognition. When Lincoln released the two, however, tensions cooled, and in the end the episode did not aid the Confederate cause.

Throughout the early years of the war, British foreign secretary Lord John Russell, Napoleon III of France, and, to a lesser extent, British Prime Minister Lord Palmerston, showed interest in the idea of recognition of the Confederacy, or at least of offering a mediation. Recognition meant certain war with the United States, and war would have meant loss of American grain, loss of exports to the United States, loss of huge investments in American securities, invasion of Canada, much higher taxes, many lives lost and a threat to British trade. Intervention was considered by the British government following the Second Battle of Bull Run, but the Union victory at the Battle of Antietam and Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation, combined with internal opposition, caused Britain to back away; the British government did allow blockade runners to be built in Britain and operated by British seamen.No country appointed any diplomat to the Confederacy, but several maintained their consuls in the South whom they had appointed before the outbreak of war.[62] In 1861, Ernst Raven applied to Richmond for approval as the Saxe-Coburg-Gotha consul, but he held citizenship in Texas and officials in Saxe-Coburg-Gotha never saw his request; they strongly supported the Union.[63] In 1863, the Confederacy expelled all foreign consuls (all of them European diplomats) for advising their subjects to refuse to serve in the Confederate army.[64]

No nation ever sent an ambassador or an official delegation to Richmond. However, they applied principles of international law that recognized the Union and Confederate sides as belligerents. Both Confederate and Union agents were allowed to work openly in British territories. For example, in Hamilton, Bermuda a Confederate agent openly worked to help blockade runners. Some state governments in northern Mexico negotiated local agreements to cover trade on the Texas border.[65]

Pope Pius IX caused a controversy during the war by writing a letter to Jefferson Davis in which he addressed Davis as the "Honorable President of the Confederate States of America." In doing so, the Pope appeared to informally (on a personal level) recognize that the CSA was a separate country. The Holy See never released a formal statement supporting or recognizing the Confederacy, however.

Confederacy at war

Armed forces

Main article: Military of the Confederate States of AmericaThe military armed forces of the Confederacy comprised three branches: Army, Navy and Marine Corps.

The Confederate military leadership included many veterans from the United States Army and United States Navy who had resigned their Federal commissions and had won appointment to senior positions in the Confederate armed forces. Many had served in the Mexican-American War (including Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis), but some such as Leonidas Polk (who had attended West Point but did not graduate) had little or no experience.

The Confederate officer corps consisted of men from both slave-owning and non-slave-owning families. The Confederacy appointed junior and field grade officers by election from the enlisted ranks. Although no Army service academy was established for the Confederacy, many colleges of the South (such as The Citadel and Virginia Military Institute) maintained cadet corps that were seen as a training ground for Confederate military leadership. A naval academy was established at Drewry’s Bluff, Virginia[66] in 1863, but no midshipmen graduated before the Confederacy's end.

The soldiers of the Confederate armed forces consisted mainly of white males aged between 16 and 28.[citation needed] The Confederacy adopted conscription in 1862. Many thousands of slaves served as laborers, cooks, and pioneers. Some freed blacks and men of color served in local state militia units of the Confederacy, primarily in Louisiana and South Carolina, but their officers deployed them for "local defense, not combat." [67] Depleted by casualties and desertions, the military suffered chronic manpower shortages. In the spring of 1865, the Confederate Congress, influenced by the public support by General Lee, approved the recruitment of black infantry units. Contrary to Lee’s and Davis’s recommendations, the Congress refused “to guarantee the freedom of black volunteers.” No more than two hundred black troops were ever raised.[68]

Victories: 1861

The American Civil War broke out in April 1861 with the Battle of Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina. Federal troops of the U.S. had retreated to Fort Sumter soon after South Carolina declared its secession on 20 December 1860.

U.S. President Buchanan had attempted to re-supply Sumter by sending the Star of the West, but Confederate forces led by cadets from The Citadel, fired upon the ship on Jan. 9, 1861, driving it away. U.S. President Abraham Lincoln also attempted to resupply Sumter. Lincoln notified South Carolina Governor Francis W. Pickens that "an attempt will be made to supply Fort Sumter with provisions only, and that if such attempt be not resisted, no effort to throw in men, arms, or ammunition will be made without further notice, [except] in case of an attack on the fort." However, suspecting just such an attempt to reinforce the fort, the Confederate cabinet decided at a meeting in Montgomery to capture Fort Sumter before the relief fleet arrived.

On April 12, 1861, Confederate troops, following orders from Jefferson Davis and his Secretary of War, fired upon the federal troops occupying Fort Sumter, forcing their surrender. Nobody was killed in the battle, though two Union soldiers did die from an accidental explosion during the surrender ceremonies. After the war, Confederate Vice President Alexander H. Stephens maintained that Lincoln's attempt to resupply Sumter was a disguised reinforcement and had provoked the war.[69] Following the Battle of Fort Sumter, Lincoln called for the states to send troops to recapture Sumter and all other federal property that had been seized in the seven seceding states[70] Lincoln issued this call before Congress could convene on the matter, and the original request from the War Department called for volunteers for only three months of duty. Lincoln's call for troops resulted in four border states deciding to secede rather than provide troops that would be marching into neighboring Southern states. Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee and North Carolina joined the Confederacy, bringing the total to 11 states. Once Virginia had joined, the Confederate States moved their capital from Montgomery, Alabama, to Richmond, Virginia. All but two major battles (Antietam and Gettysburg) took place in Confederate territory.

Incursions: 1862

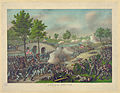

-

Union dead buried at Antietam,

war aim for Union to relent[71]

By 1862, the Union had taken control of New Orleans, and had gained control of the contested northernmost slave states (Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland, Delaware and West Virginia). Two major Confederate incursions into Union territory in 1862, Lee's invasion of Maryland and Braxton Bragg's invasion of Kentucky were decisively repulsed, and both armies barely escaped capture.

Nevins (1960) argues that 1862 was the high water mark of the Confederacy, and that the failures of the two invasions were the same: lack of manpower, lack of supplies—there were hardly any new shoes or boots—and exhaustion after long marches. Weak national leadership meant that Davis's favorites like Bragg remained in command of an army he could not handle, and the disorganized overall direction stood in sharp contrast to the much improved organization in Washington.

With another 10,000 men Lee and Bragg might have prevailed, but their goal of gaining new soldiers failed because the border states did not respond to their pleas.[72]

Anaconda: 1863–1864

By 1863 the Union held control of most of Tennessee; with the fall of Vicksburg, Mississippi, on July 4 of that year, the Union gained complete control over the Mississippi River, cutting off the westernmost portions of the Confederacy (Arkansas, Louisiana, Texas, and the Oklahoma and Arizona Territories).

In 1864, the Union took Mobile, Alabama, the last major port on the Gulf Coast, and by September 1864 Atlanta fell to Union troops, paving the way for the March to the Sea by William Tecumseh Sherman's forces; he reached Savannah by the end of the year, then moved north into the Carolinas, devastating a wide swath of the Confederate heartland. The major defeat at the Battle of Nashville in December destroyed the main Confederate forces in the west.

Collapse: 1865

Senior Confederate officials met with Lincoln and his aides in February, but rejected Lincoln's invitation to return to the Union (which came with a suggestion the Union would buy the slaves). It was independence or nothing, but Lee's army was wracked by desertions and could barely hold on in the trenches around Richmond.

-

Armory, Richmond, Va

industry destroyed

When the Union broke through Lee's lines at Petersburg, the main strong point that controlled the capital, Richmond fell immediately. Lee raced west to escape, but was caught and surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox, Virginia on April 9, 1865, marking the end of the Confederacy.

Some high officials escaped to Europe but Union patrols captured President Davis on May 10; all remaining Confederate forces surrendered by June 1865. The U.S. Army took control of the Confederate areas and there was no post-surrender insurgency or guerrilla warfare against the army, but there was a great deal of local violence, feuding and revenge killings.[73]

Historian Gary Gallagher concludes: "The Confederacy capitulated in the spring of 1865 because northern armies had demonstrated their ability to crush organized southern military resistance....Civilians who had maintained faith in their defenders despite material hardship and social disruption similarly recognized that the end had come.... Most Confederates knew that as a people they had expended blood and treasure in profusion before ultimately collapsing in the face of northern power sternly applied."[74]

"Died of states' rights"

Historian Frank Lawrence Owsley argued that the Confederacy "died of states' rights."[4][75] According to Owsley, strong-willed governors and state legislatures in the South refused to give the central government the soldiers and money it needed because they feared that Richmond would encroach on the rights of the states. Georgia's governor Joseph Brown warned that he saw the signs of a deep-laid conspiracy on the part of Jefferson Davis to destroy states' rights and individual liberty. Brown declaimed: "Almost every act of usurpation of power, or of bad faith, has been conceived, brought forth and nurtured in secret session." He saw granting the Confederate government the power to draft soldiers as the "essence of military despotism."[76]

-

Joseph E. Brown, Ga Governor -

Pendleton Murrah, Tx Governor -

A. Stephens, Vice President

In 1863 governor Pendleton Murrah of Texas insisted that his State needed Texas troops for self-defense (against Native Americans or against a threatened Union advance), and refused to send them East.[77] Zebulon Vance, the governor of North Carolina, had a reputation for hostility to Davis and to his demands. North Carolina showed intense opposition to conscription, resulting in very poor results for recruiting. Governor Vance's faith in states' rights drove him into a stubborn opposition.[78]

Historian George Rable wrote:

For Alexander Stephens, any accommodation would only weaken the republic, and he therefore had no choice but to break publicly with the Confederate administration and the president. In an extraordinary three-hour speech to the legislature on the evening of March 16 [1864], the vice-president carefully outlined his position. Allowing Davis to make "arbitrary arrests" and to draft state officials conferred on him more power than the English Parliament had ever bestowed on the king. History proved the dangers of such unchecked authority.....The Confederate government intended to suppress the peace meetings in North Carolina, he warned, and "put a muzzle upon certain presses" (i.e., the Raleigh Standard) in order to control elections in that state.[79]

Echoing Patrick Henry's "give me liberty or give me death" Stephens warned the Southerners they should never view liberty as "subordinate to independence" because the cry of "independence first and liberty second" was a "fatal delusion". As Rable concludes, "For Stephens, the essence of patriotism, the heart of the Confederate cause, rested on an unyielding commitment to traditional rights. In his idealist vision of politics, military necessity, pragmatism, and compromise meant nothing".[80]

Despite political differences within the Confederacy, no political parties were formed. Historian William C. Cooper Jr. wrote that "at the birth of their new nation, Confederates, in the language of the Founding Fathers, denounced the legitimacy of parties. Anti-partyism became an article of political faith. Almost nobody, even Davis’s most fervent antagonists, advocated parties."[81] This lack of a functioning two party system, according to historian David M. Potter, caused "real and direct damage" to the Confederate war effort since it prevented the formulation of any effective alternatives to the Davis administration's policies in conducting the war.[82]

The survival of the Confederacy depended on a strong base of civilians and soldiers devoted to victory. The soldiers performed well, though increasing numbers deserted in the last year of fighting, and the Confederacy never succeeded in replacing casualties as the Union could. The civilians, although enthusiastic in 1861–62, seem to have lost faith in the future of the Confederacy by 1864, and instead looked to protect their homes and communities. As Rable explains, "As the Confederacy shrank, citizens' sense of the cause more than ever narrowed to their own states and communities. This contraction of civic vision was more than a crabbed libertarianism; it represented an increasingly widespread disillusionment with the Confederate experiment."[83]

Government and politics

Constitution

Main article: Confederate States ConstitutionThe Southern leaders met in Montgomery, Alabama, to write their constitution. Much of the Confederate States Constitution replicated the United States Constitution verbatim, but it contained several explicit protections of the institution of slavery including provisions for the recognition and protection of negro slavery in any new state admitted to the Confederacy. It maintained the existing ban on international slave-trading while protecting the existing internal trade of slaves among slaveholding states.

In certain areas, the Confederate Constitution gave greater powers to the states (or curtailed the powers of the central government more) than the U.S. Constitution of the time did, but in other areas, the states actually lost rights they had under the U.S. Constitution. Although the Confederate Constitution, like the U.S. Constitution, contained a commerce clause, the Confederate version prohibited the central government from using revenues collected in one state for funding internal improvements in another state. The Confederate Constitution's equivalent to the U.S. Constitution's general welfare clause prohibited protective tariffs (but allowed tariffs for providing domestic revenue), and spoke of "carry[ing] on the Government of the Confederate States" rather than providing for the "general welfare". State legislatures had the power to impeach officials of the Confederate government in some cases. On the other hand, the Confederate Constitution contained a Necessary and Proper Clause and a Supremacy Clause that essentially duplicated the respective clauses of the U.S. Constitution. The Confederate Constitution also incorporated each of the 12 amendments to the U.S. Constitution that had been ratified up to that point.

The Confederate Constitution did not specifically include a provision allowing states to secede; the Preamble spoke of each state "acting in its sovereign and independent character" but also of the formation of a "permanent federal government". During the debates on drafting the Confederate Constitution, one proposal would have allowed states to secede from the Confederacy. The proposal was tabled with only the South Carolina delegates voting in favor of considering the motion.[84] The Confederate Constitution also explicitly denied States the power to bar slaveholders from other parts of the Confederacy from bringing their slaves into any state of the Confederacy or to interfere with the property rights of slave owners traveling between different parts of the Confederacy. In contrast with the language of the United States Constitution, the Confederate Constitution overtly asked God's blessing ("...invoking the favor and guidance of Almighty God...").

Executive

Confederate Executive, 1861 - 1865

Table of departments, officers and termsOffice Name Term President Jefferson Davis 1861–1865 Vice President Alexander Stephens 1861–1865 Secretary of State Robert Toombs 1861 Robert M.T. Hunter 1861–1862 Judah P. Benjamin 1862–1865 Secretary of the Treasury Christopher Memminger 1861–1864 George Trenholm 1864–1865 John H. Reagan 1865 Secretary of War Leroy Pope Walker 1861 Judah P. Benjamin 1861–1862 George W. Randolph 1862 James Seddon 1862–1865 John C. Breckinridge 1865 Secretary of the Navy Stephen Mallory 1861–1865 Postmaster General John H. Reagan 1861–1865 Attorney General Judah P. Benjamin 1861 Thomas Bragg 1861–1862 Thomas H. Watts 1862–1863 George Davis 1864–1865

First Cabinet: J. Benjamin, S. Mallory, C. Memminger, A. Stephens, L. Walker, Jeff Davis, J.H. Reagan and R. Toombs. The Constitution provided for a President of the Confederate States of America, elected to serve a six-year term but without the possibility of re-election. Unlike the Union Constitution, the Confederate Constitution gave the president the ability to subject a bill to a line item veto, a power also held by some state governors.

The Confederate Congress could overturn either the general or the line item vetoes with the same two-thirds majorities that are required in the U.S. Congress. In addition, appropriations not specifically requested by the executive branch required passage by a two-thirds vote in both houses of Congress. The only person to serve as president was Jefferson Davis, due to the Confederacy being defeated before the completion of his term.

Legislative

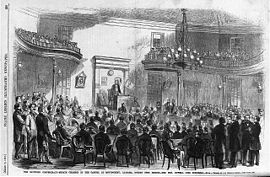

Main article: Confederate Congress Provisional Congress, Montgomery, AL

Provisional Congress, Montgomery, AL

As its legislative branch, the Confederate States of America instituted the Confederate Congress. Like the United States Congress, the Confederate Congress consisted of two houses:

- the Confederate Senate, whose membership included two senators from each state (and chosen by the state legislature)

- the Confederate House of Representatives, with members popularly elected by properly enfranchised residents of the individual states

Provisional Congress

For the first year, the unicameral Provisional Confederate Congress functioned as the Confederacy's legislative branch.President of the Provisional Congress

- Howell Cobb, Sr. of Georgia, February 4, 1861 – February 17, 1862

Presidents pro tempore of the Provisional Congress

- Robert Woodward Barnwell of South Carolina, February 4, 1861

- Thomas Stanhope Bocock of Virginia, December 10–21, 1861 and January 7–8, 1862

- Josiah Abigail Patterson Campbell of Mississippi, December 23–24, 1861 and January 6, 1862

Sessions of the Confederate Congress

Tribal Representatives to Confederate Congress

- Elias Cornelius Boudinot 1862–65, Cherokee

- Samuel Benton Callahan Unknown years, Creek, Seminole

- Burton Allen Holder 1864–1865, Chickasaw

- Robert McDonald Jones 1863–65, Choctaw

Judicial

The Confederate Constitution outlined a judicial branch of the government, but the ongoing war and resistance from states-rights advocates, particularly on the question of whether it would have appellate jurisdiction over the state courts, prevented the creation or seating of the "Supreme Court of the Confederate States"; the state courts generally continued to operate as they had done, simply recognizing the C.S.A. as the national government.[85]

-

Jesse J. Finley, Fl District -

Henry R. Jackson Ga District -

Asa Biggs, NC District -

Andrew Magrath, SC District

Confederate district courts were authorized by Article III, Section 1, of the Confederate Constitution,[86] and President Davis appointed judges within the individual states of the Confederate States of America.[86] In many cases, the same U.S. Federal District Judges were appointed as Confederate States District Judges. Confederate district courts began reopening in the spring of 1861 handling many of the same type cases as had been done before. Prize cases, in which Union ships were captured by the Confederate Navy or raiders and sold through court proceedings, were heard until the blockade of southern ports made this impossible. After a Sequestration Act was passed by the Confederate Congress, the Confederate district courts heard many cases in which enemy aliens (typically Northern absentee landlords owning property in the South) had their property sequestered (i.e., seized) by Confederate Receivers. When the matter came before the Confederate court, the property owner could not appear because he was unable to travel across the front lines between Union and Confederate forces. Thus, the C.S. District Attorney won the case by default, the property was typically sold, and the money used to further the Southern war effort. Eventually, because there was no Confederate Supreme Court, sharp attorneys like South Carolina's Edward McCrady began filing appeals. This prevented their clients' property from being sold until a supreme court could be constituted to hear the appeal, which never occurred.[86] Where Federal troops gained control over parts of the Confederacy and re-established civilian government, U.S. district courts sometimes resumed jurisdiction.[87]

Supreme Court – not established.

District Courts – judges

- Alabama William G. Jones 1861–1865

- Arkansas Daniel Ringo 1861–1865

- Florida Jesse J. Finley 1861–1862

- Georgia Henry R. Jackson 1861, Edward J. Harden 1861–1865

- Louisiana Edwin Warren Moise 1861–1865

- Mississippi Alexander Mosby Clayton 1861–1865

- North Carolina Asa Biggs 1861–1865

- South Carolina Andrew G. Magrath 1861–1864, Benjamin F. Perry 1865

- Tennessee West H. Humphreys 1861–1865

- Texas-East William Pinckney Hill 1861–1865

- Texas-West Thomas J. Devine 1861–1865

- Virginia-East James D. Halyburton 1861–1865

- Virginia-West John W. Brockenbrough 1861–1865

Post Office

When the Confederacy was formed and its seceding states broke from the Union, it was at once confronted with the arduous task of providing its citizens with a mail delivery system, and in the midst of the American Civil War the newly formed Confederacy created and established the Confederate Post Office. One of the first undertakings in establishing the Post Office was the appointment of John H. Reagan to the position of Postmaster General, by Jefferson Davis in 1861, making him the first Postmaster General of the Confederate Post Office as well as a member of Davis' presidential cabinet. Through Reagan's resourcefulness and remarkable industry, he had his department assembled, organized and in operation before the other Presidential cabinet members had their departments fully operational.[88][89]

Jefferson Davis

The 1st stamp, Issue of 1861When the Civil War began, the U.S. Post Office still delivered mail from the seceded states for a brief period of time. Mail that was postmarked after the date of a state’s admission into the Confederacy through May 31, 1861 and bearing US (Union) Postage was still delivered.[90] After this time, private express companies still managed to carry some of the mail across enemy lines. Later mail that crossed lines had to be sent by 'Flag of Truce' and was only allowed to pass at two specific points: Mail sent from the South to Northern states was received, opened and inspected at Fortress Monroe on the Virginia coast before being passed on into the U.S. mail stream. Mail sent from the North to any of the seceded states passed at City Point, also in Virginia, where it was also inspected before being sent on.[91][92]

With the chaos of the war, a working postal system was more important than ever for the Confederacy. The Civil War had divided family members and friends and consequently letter writing naturally increased dramatically across the entire divided nation, especially to and from the men who were away serving in an army. Mail delivery was also important for the Confederacy for a myriad of business and military reasons. Because of the Union blockade, basic supplies were always in demand and so getting mailed correspondence out of the country to suppliers was imperative to the successful operation of the Confederacy. Volumes of material have been written about the Blockade runners who evaded Union ships on blockade patrol, usually at night, and who moved cargo and mail in and out of the Confederate States throughout the course of the war. Of particular interest to students and historians of the American Civil War is Prisoner of War mail and Blockade mail as these items were often involved with a variety of military and other war time activities. The postal history of the Confederacy along with surviving Confederate mail has helped historians document the various people, places and events that were involved in the American Civil War as it unfolded.[93]

Civil liberties

The Confederacy actively used the army to arrest people suspected of loyalty to the United States. Historian Mark Neely found 4,108 names of men arrested and estimated a much larger total.[94] The Confederacy arrested pro-Union civilians in the South at about the same rate as the Union arrested pro-Confederate civilians in the North. Neely concludes:

The Confederate citizen was not any freer than the Union citizen – and perhaps no less likely to be arrested by military authorities. In fact, the Confederate citizen may have been in some ways less free than his Northern counterpart. For example, freedom to travel within the Confederate states was severely limited by a domestic passport system.[95]Economy

Main article: Economy of the Confederate States of AmericaNational production

The Confederacy started its existence as an agrarian economy with exports, to a world market, of cotton, and, to a lesser extent, tobacco and sugarcane. Local food production included grains, hogs, cattle, and gardens.

The 11 states produced $155 million in manufactured goods in 1860, chiefly from local grist-mills, and lumber, processed tobacco, cotton goods and naval stores such as turpentine. By the 1830s, the 11 states produced more cotton than all of the other countries in the world combined.

The Confederacy adopted a low tariff of 15 per cent, but imposed it on all imports from other countries, including the Union states.[96] The tariff mattered little; the Union blockade minimized commercial traffic through the Confederacy's ports, and very few people paid taxes on goods smuggled from the Union states. The government collected about $3.5 million in tariff revenue from the start of their war against the Union to late 1864. The lack of adequate financial resources led the Confederacy to finance the war through printing money, which led to high inflation.

The requirements of its military encouraged the Confederate government to take a dirigiste-style approach to industrialization.[97] But such efforts faced setbacks: Union raids and in particular Sherman's scorched-earth campaigning destroyed much economic infrastructure.[98]

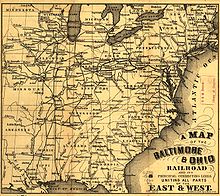

Transportation systems

Main article: Confederate railroads in the American Civil WarIn peacetime, the vast system of navigable rivers allowed for cheap and easy transportation of farm products. The railroad system, built as a supplement, tied plantation areas to the nearest river or seaport. The vast geography of the Confederacy made logistics difficult for the Union, and the Union armies assigned many of their soldiers to garrison captured areas and to protect rail lines. Nevertheless, the Union Navy had seized most of the navigable rivers by 1862, making its own logistics easy and Confederate movements difficult. After the fall of Vicksburg in July 1863, it became impossible for Confederate units to cross the Mississippi: Union gunboats constantly patrolled the river. The South thus lost the use of its western regions.

locomotive "Fred Leach" on the

Orange and Alexandria Railroad[99]At the end of 1860, the Southern rail network was disjointed and plagued by break of gauge as well as lack of interchange.[100] In addition, most rail lines lead from coastal or river ports to inland cities, with few lateral railroads. This made travel between adjacent states by rail difficult.

The outbreak of war had a depressing effect on the economic fortunes of the railroad system in Confederate territory. The hoarding of the cotton crop in an attempt to entice European intervention left railroads bereft of their main source of income.[101] Many had to lay off employees, and in particular, let go skilled technicians and engineers.[102] For the early years of the war, the Confederate government had a hands-off approach to the railroads. Only in mid-1863 did the Confederate government initiate an overall policy, and it was confined solely to aiding the war effort.[103] With the legislation of impressment the same year, railroads and their rolling stock came under the de facto control of the military.

In the last year before the end of the war, the Confederate railroad system stood permanently on the verge of collapse. There was no new equipment and raids on both sides systematically destroyed key bridges, as well as locomotives and freight cars. Spare parts were cannibalized; feeder lines were torn up to get replacement rails for trunk lines, and the heavy use of rolling stock wore them out.[104]

Financial instruments

Both the individual Confederate states and later the Confederate government printed Confederate States of America dollars as paper currency in various denominations, much of it signed by the Treasurer Edward C. Elmore. During the course of the war these severely depreciated and eventually became worthless. Many bills still exist, although in recent years copies have proliferated.

The Confederate government initially financed the war effort mostly through tariffs on imports, export taxes, and voluntary donations of coins and bullion. However, after the imposition of a self-embargo on cotton sales to Europe in 1861, these sources of revenue dried up and the Confederacy increasingly turned to issuing debt and printing money to pay for war expanses. The Confederate States politicians were worried about angering the general population with hard taxes. A tax increase might disillusion many Southerners, so the Confederacy resorted to printing more money. As a result inflation increased and remained a problem for the southern states throughout the rest of the war.[105]

The Treasury also issued paper bonds in large numbers, and the Post Office produced a considerable number of postage stamps; both stamps and bonds (and especially bond coupons) remain readily available. The philatelic market regards as far more valuable the stamps placed on envelopes that were actually used during the war.

At the time of their secession, the states (and later the Confederate government) took over the national mints in their territories: the Charlotte Mint in North Carolina, the Dahlonega Mint in Georgia, and the New Orleans Mint in Louisiana. During 1861, the first two produced small amounts of gold coinage, the latter half dollars. Since the mints used the current dies on hand, these issues remain indistinguishable from those minted by the Union.

However the four half dollars with a Confederate (rather than U.S.) reverse, mentioned below, used an obverse die that had a small crack. Thus "regular" 1861-O halves with this crack probably were among the 962,633 pieces struck under Confederate authority.[106]

In 1861 plans also originated to produce Confederate coins. The New Orleans Mint produced dies and four specimen half dollars, but a lack of bullion prevented any further minting. A jeweler in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, manufactured a dozen pennies under an agreement, but did not deliver them for fear of arrest. Over the years copies of both denominations have appeared. More details and pictures of the original issues appear in A Guide Book of United States Coins.

Devastation by 1865

By the end of the war deterioration of the Southern infrastructure was widespread. The number of civilian deaths is unknown. Most of the war was fought in Virginia and Tennessee, but every Southern state was affected as well as Maryland, West Virginia, Kentucky Missouri, and Indian Territory. Texas and Florida saw the least military action. Much of the damage was caused by military action, but most was caused by lack of repairs and upkeep, and by deliberately using up resources. Historians have recently estimated how much of the devastation was caused by military action.[107] Of 645 counties in 9 Confederate states (excluding Texas and Florida), there was Union military action in 56% of them, containing 63% of the 1860 white population and 64% of the slaves in 1860; however by the time the action took place some people had fled to safer areas, so the exact population exposed to war is unknown.

-

Navy Yard, Norfolk Va

The 11 Confederate states in the 1860 census had 297 towns and cities with 835,000 people; of these 162 with 681,000 people were at one point occupied by Union forces. Eleven were destroyed or severely damaged by war action, including Atlanta (with an 1860 population of 9,600), Charleston, Columbia, and Richmond (with prewar populations of 40,500, 8,100, and 37,900, respectively); the eleven contained 115,900 people in the 1860 census, or 14% of the urban South. Historians have not estimated what their actual population was when Union forces arrived. The number of people (as of 1860) who lived in the destroyed towns represented just over 1% of the Confederacy's 1860 population. In addition, 45 court houses were burned (out of 830). The South's agriculture was not highly mechanized. The value of farm implements and machinery in the 1860 Census was $81 million; by 1870, there was 40% less, worth just $48 million. Many old tools had broken through heavy use; new tools were rarely available; even repairs were difficult.[108]

The economic losses affected everyone. Banks and insurance companies were mostly bankrupt. Confederate currency and bonds were worthless. The billions of dollars invested in slaves vanished. However, most debts were left behind. Most farms were intact but most had lost their horses, mules and cattle; fences and barns were in disrepair. Prices for cotton had plunged. The rebuilding would take years and require outside investment because the devastation was so thorough. One historian has summarized the collapse of the transportation infrastructure needed for economic recovery:[109]

- "One of the greatest calamities which confronted Southerners was the havoc wrought on the transportation system. Roads were impassable or nonexistent, and bridges were destroyed or washed away. The important river traffic was at a standstill: levees were broken, channels were blocked, the few steamboats which had not been captured or destroyed were in a state of disrepair, wharves had decayed or were missing, and trained personnel were dead or dispersed. Horses, mules, oxen, carriages, wagons, and carts had nearly all fallen prey at one time or another to the contending armies. The railroads were paralyzed, with most of the companies bankrupt. These lines had been the special target of the enemy. On one stretch of 114 miles in Alabama, every bridge and trestle was destroyed, cross-ties rotten, buildings burned, water-tanks gone, ditches filled up, and tracks grown up in weeds and bushes. . . . Communication centers like Columbia and Atlanta were in ruins; shops and foundries were wrecked or in disrepair. Even those areas bypassed by battle had been pirated for equipment needed on the battlefront, and the wear and tear of wartime usage without adequate repairs or replacements reduced all to a state of disintegration."

Flags

National flags

Main article: Flags of the Confederate States of AmericaThe first official flag of the Confederate States of America—called the "Stars and Bars" – originally had seven stars, representing the first seven states that initially formed the Confederacy. As more states seceded, more stars were added, until the total was 13 (two stars were added for the divided states of Kentucky and Missouri). However, during the Battle of Bull Run (or First Manassas) it sometimes proved difficult to distinguish the Stars and Bars from the Union flag. To rectify the situation, a separate "Battle Flag" was designed for use by troops in the field. Also known as the "Southern Cross", many variations sprang from the original square configuration. Although it was never officially adopted by the Confederate government, the popularity of the Southern Cross among both soldiers and the civilian population was a primary reason why it was made the main color feature when a new national flag was adopted in 1863. This new standard—known as the "Stainless Banner" – consisted of a lengthened white field area with a Battle Flag canton. This flag too had its problems when used in military operations as, on a windless day, it could easily be mistaken for a flag of truce or surrender. Thus, in 1865, a modified version of the Stainless Banner was adopted. This final national flag of the Confederacy kept the Battle Flag canton, but shortened the white field and added a vertical red bar to the fly end.

Because of its depiction in the 20th-century[citation needed] and popular media, many people consider the rectangular battle flag design as being synonymous with "the Confederate Flag", even though most were square, and none were ever adopted as Confederate national flags. The generic version of the banner familiar today was used as the Confederate Naval Jack and the Battle Flag of the Army of Tennessee as well as other units.

States and flags

Member State Flag Ordinance of Secession Date of Admission Under predominant

Union controlReadmitted to

representation

in CongressSouth Carolina

Dec. 20, 1860 Feb. 8, 1861 1865 July 9, 1868 Mississippi

Jan. 9, 1861 Feb. 8, 1861 1863 Feb. 23, 1870 Florida

Jan. 10, 1861 Feb. 8, 1861 1865 June 25, 1868 Alabama

Jan. 11, 1861 Feb. 8, 1861 1865 July 13, 1868 Georgia

Jan. 19, 1861 Feb. 8, 1861 1865 1st Date July 21, 1868;

2nd Date July 15, 1870Louisiana

Jan. 26, 1861 Feb. 8, 1861 1863 July 9, 1868 Texas

Feb. 1, 1861 March 2, 1861 1865 March 30, 1870 Virginia

April 17, 1861 May 7, 1861 1865;

(1862/63 for West Virginia)Jan. 26, 1870 Arkansas

May 6, 1861 May 18, 1861 1864 June 22, 1868 North Carolina

May 20, 1861 May 21, 1861 1865 July 4, 1868 Tennessee

June 8, 1861 July 2, 1861 1863 July 24, 1866 Missouri (exiled government)

Oct. 31, 1861 Nov. 28, 1861 1861 Unionist govt. appointed by Missouri Constitutional Convention 1861 Kentucky (Russellville Convention)

Nov. 20, 1861 Dec. 10, 1861 1861 Elected Union and unelected rump Confederate governments from 1861 Geography

The Confederate States of America claimed a total of 2,919 miles (4,698 km) of coastline, thus a large part of its territory lay on the seacoast with level and often sandy or marshy ground. Most of the interior portion consisted of arable farmland, though much was also hilly and mountainous, and the far western territories were deserts. The lower reaches of the Mississippi River bisected the country, with the western half often referred to as the Trans-Mississippi. The highest point (excluding Arizona and New Mexico) was Guadalupe Peak in Texas at 8,750 feet (2,667 m).

Climate

Much of the area claimed by the Confederate States of America had a humid subtropical climate with mild winters and long, hot, humid summers. The climate and terrain varied from vast swamps (such as those in Florida and Louisiana) to semi-arid steppes and arid deserts west of longitude 100 degrees west. The subtropical climate made winters mild but allowed infectious diseases to flourish. Consequently, on both sides more soldiers died from disease than were killed in combat,[110] a fact hardly atypical of pre–World War I conflicts.

Rural/urban configuration

The area claimed by the Confederate States of America consisted overwhelmingly of rural land. Few urban areas had populations of more than 1,000 – the typical county seat had a population of fewer than 500 people. Cities were rare. Of the twenty largest U.S. cities in the 1860 census, only New Orleans lay in Confederate territory [111] – and the Union captured New Orleans in 1862. Only 13 Confederate-controlled cities ranked among the top 100 U.S. cities in 1860, most of them ports whose economic activities vanished or suffered severely in the Union blockade. The population of Richmond swelled after it became the Confederate capital, reaching an estimated 128,000 in 1864.[112] Other large Southern cities (Baltimore, St. Louis, Louisville, and Washington, D.C. as well as Wheeling, West Virginia, and Alexandria, Virginia) never came under the control of the Confederate government.

The cities of the Confederacy included most prominently in order of size of population:

# City 1860 population 1860 U.S. rank Return to U.S. control 1. New Orleans, Louisiana 168,675 6 1862 2. Charleston, South Carolina 40,522 22 1865 3. Richmond, Virginia 37,910 25 1865 4. Mobile, Alabama 29,258 27 1865 5. Memphis, Tennessee 22,623 38 1862 6. Savannah, Georgia 22,619 41 1864 7. Petersburg, Virginia 18,266 50 1865 8. Nashville, Tennessee 16,988 54 1862 9. Norfolk, Virginia 14,620 61 1862 10. Augusta, Georgia 12,493 77 1865 11. Columbus, Georgia 9,621 97 1865 12. Atlanta, Georgia 9,554 99 1864 13. Wilmington, North Carolina 9,553 100 1865 (See also Atlanta in the Civil War, Charleston, South Carolina, in the Civil War, Nashville in the Civil War, New Orleans in the Civil War, Wilmington, North Carolina, in the American Civil War, and Richmond in the Civil War).

Demographics

The United States Census of 1860 [113] gives a picture of the overall 1860 population of the areas that joined the Confederacy. Note that population-numbers exclude non-assimilated Indian tribes.

State Total

PopulationTotal

# of

SlavesTotal

# of

HouseholdsTotal

Free

PopulationTotal #[114]

Slaveholders% of Free

Population

Owning

Slaves[115]Slaves

as % of

PopulationTotal

free

coloredAlabama 964,201 435,080 96,603 529,121 33,730 6% 45% 2,690 Arkansas 435,450 111,115 57,244 324,335 11,481 4% 26% 144 Florida 140,424 61,745 15,090 78,679 5,152 7% 44% 932 Georgia 1,057,286 462,198 109,919 595,088 41,084 7% 44% 3,500 Louisiana 708,002 331,726 74,725 376,276 22,033 6% 47% 18,647 Mississippi 791,305 436,631 63,015 354,674 30,943 9% 55% 773 North Carolina 992,622 331,059 125,090 661,563 34,658 5% 33% 30,463 South Carolina 703,708 402,406 58,642 301,302 26,701 9% 57% 9,914 Tennessee 1,109,801 275,719 149,335 834,082 36,844 4% 25% 7,300 Texas 604,215 182,566 76,781 421,649 21,878 5% 30% 355 Virginia 1,596,318 490,865 201,523 1,105,453 52,128 5% 31% 58,042 Total 9,103,332 3,521,110 1,027,967 5,582,222 316,632 6% 39% 132,760 (Figures for Virginia include the future West Virginia.)

Age structure 0–14 years 15–59 years 60 years and over Total White males 43% 52% 4% White females 44% 52% 4% Male slaves 44% 51% 4% Female slaves 45% 51% 3% Free black males 45% 50% 5% Free black females 40% 54% 6% Total population 44% 52% 4% (Rows may not total to 100% due to rounding)

In 1860 the areas that later formed the 11 Confederate States (and including the future West Virginia) had 132,760 (1.46%) free blacks. Males made up 49.2% of the total population and females 50.8% (whites: 48.60% male, 51.40% female; slaves: 50.15% male, 49.85% female; free blacks: 47.43% male, 52.57% female).[116]

Military leaders

Military leaders of the Confederacy (with their state or country of birth and highest rank)[117] included:

- Robert E. Lee (Virginia) – General and General-in-Chief (1865)

- Albert Sidney Johnston (Kentucky) – General

- Joseph E. Johnston (Virginia) – General

- Braxton Bragg (North Carolina) – General

- P.G.T. Beauregard (Louisiana) – General

- Richard S. Ewell (Virginia) – Lieutenant General

- Francis Marion Cockrell (Missouri) – Brigadier General for CSA. Following the Civil War, he received a Presidential Pardon and served as U.S. Senator from Missouri for 30 years.

- James Longstreet (South Carolina) – Lieutenant General

- Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson (Virginia now West Virginia) – Lieutenant General

- John Hunt Morgan (Kentucky) – Brigadier General

- A.P. Hill (Virginia) – Lieutenant General

- John Bell Hood (Kentucky) – Lieutenant General (temporary General)

- Wade Hampton III (South Carolina) – Lieutenant General

- Nathan Bedford Forrest (Tennessee) – Lieutenant General

- John Singleton Mosby, the "Grey Ghost of the Confederacy" (Virginia) – Colonel

- J.E.B. Stuart (Virginia) – Major General

- Edward Porter Alexander (Georgia) – Brigadier General

- Franklin Buchanan (Maryland) – Admiral

- Raphael Semmes (Maryland) – Rear Admiral

- Stand Watie (Georgia) – Brigadier General (last to surrender)

- Leonidas Polk (North Carolina) – Lieutenant General

- Sterling Price (Missouri) – Major General

- Jubal Anderson Early (Virginia) – Lieutenant General

- Richard Taylor (Kentucky) – Lieutenant General (Son of U.S. President Zachary Taylor)

- Stephen Dodson Ramseur (North Carolina) – Major General

- Camille Armand Jules Marie, Prince de Polignac – (France) Major General

- John Austin Wharton (Tennessee) – Major General

- Thomas L. Rosser (Virginia) – Major General

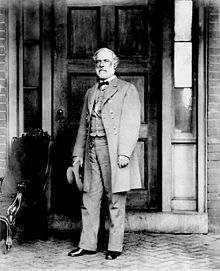

General Robert E. Lee: for many, the face of the Confederate army

General Robert E. Lee: for many, the face of the Confederate army

- Patrick Cleburne (Ireland) – Major General

- William N. Pendleton (Virginia) – Brigadier General

- Heros von Borcke (Prussia) – Lieutenant Colonel

For more details on this topic, see History of Confederate States Army Generals.See also

- Conclusion of the American Civil War

- Confederate Post Office

- Confederate war finance

- Confederate Seal

- History of the Southern United States

- Prisoner of war prisons and camps

- Postage stamps and postal history of the Confederate States

- Golden Circle (proposed country)

- Confederate Patent Office

- Confederate colonies

- Confederados

- For the 2004 film: C.S.A.: The Confederate States of America

Notes

- ^ a b "Preventing Diplomatic Recognition of the Confederacy, 1861–1865". U.S. Department of State. http://history.state.gov/milestones/1861-1865/Confederacy.

- ^ a b McPherson, James M. (2007). This mighty scourge: perspectives on the Civil War. Oxford University Press US. p. 65. ISBN 9780195313666. http://books.google.com/?id=bJEINL6bakYC&pg=PA65&lpg=PA65&dq=confederacy+recognition.

- ^ Freehling, William W., “The Road To Disunion: Secessionists Triumphant”, Vol. II, 2007, ISBN 978-0-19-505815-4 p.485–6

- ^ a b Frank L. Owsley, State Rights in the Confederacy (Chicago, 1925).

- ^ Cooper, William J.; Terrill, Tom E. (2009). The American South: a history. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. xix. ISBN 0-7425-6095-3.

- ^ a b Freehling, William W. (1990). The Road to Disunion: Volume II, Secessionists Triumphant. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-505815-4. p. 398

- ^ Emory M. Thomas, The Confederate Nation: 1861–1865 (1979), pp. 83–84

- ^ Faust, Drew Gilpin (1988). The creation of Confederate nationalism : ideology and identity in the Civil War South. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. p. 59. ISBN 0807115096.

- ^ Murrin, John (2001). Liberty, Equality, Power. p. 1000. ISBN 0-495-09176-6.

- ^ McPherson pp. 232–233.

- ^ McPherson pg. 244. The text of Alexander Stephens' "Cornerstone Speech".

- ^ Davis, William C. (1994). A government of our own : the making of the Confederacy. New York: Free Press. pp. 294–295. ISBN 978-0-02-907735-1.

- ^ "What I Really Said in the Cornerstone Speech".Stephens, Alexander Hamilton; Avary, Myrta Lockett. (1998). Recollections of Alexander H. Stephens : his diary kept when a prisoner at Fort Warren, Boston Harbor, 1865, giving incidents and reflections of his prison life and some letters and reminiscence. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-2268-6.

- ^ The text of the Declaration of the Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union.