- Military of the Confederate States of America

-

The Military of the Confederate States of America comprised three branches:

- Confederate States Army - The Confederate States Army (CS Army) the land-based military operations. The CS Army was established in two phases with provisional and permanent organizations, which existed concurrently.

- The Provisional Army of the Confederate States (PACS) was authorized by Act of Congress on February 23, 1862, and began organizing on April 27.

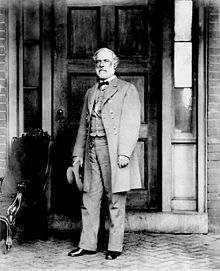

- The Army of the Confederate States of America (ACSA) was the regular army, organized by Act of Congress on March 6, 1861.[1] It was authorized to include 15,015 men, including 744 officers, but this level was never achieved. The men serving in the highest rank as Confederate States Generals, such as Samuel Cooper and Robert E. Lee, were enrolled in the ACSA to ensure that they outranked all militia officers.

- Confederate States State Militias were organized and commanded by the state governments, similar to those authorized by the United States Militia Act of 1792.

- Confederate Home Guard - a somewhat loosely organized though nevertheless legitimate organization that was under the vague direction and authority of the Confederate States of America, working in coordination with the Confederate Army, and was tasked with both the defense of the Confederate home front during the American Civil War, as well as to help track down and capture Confederate Army deserters.

- Confederate States Navy - responsible for Confederate naval operations during the American Civil War. The two major tasks of the Confederate Navy during the whole of its existence were the protection of Southern harbors and coastlines from outside invasion, and making the war costly for the North by attacking merchant ships and breaking the Union Blockade.

- Confederate States Marine Corps - a branch of the Confederate States Navy, was established by an act of the Congress of the Confederate States on March 16, 1861. The CSMC's manpower was initially authorized at 45 officers and 944 enlisted men, and was increased on September 24, 1862 to 1026 enlisted men. The organization of the Marines began at Montgomery, Alabama and was completed at Richmond, Virginia when the capital of the Confederate States of America was moved to that location. The CSMC headquarters and main training facilities remained in Richmond, Virginia throughout the war, located at Camp Beall on Drewry's Bull and at the Gosport Shipyard in Norfolk, Virginia.[2]

Members of all the Confederate States military forces, to include the Army, the Navy and the Marine Corps were often referred to as "Confederates", and members of the CS Army were referred to as "Confederate soldiers".

Contents

Command and Control

Control and operation of the Confederate States Army was administered by the Confederate States War Department, which was established by the Confederate Provisional Congress in an act on February 21, 1861. The Confederate Congress gave control over military operations, and authority for mustering state forces and volunteers to the President of the Confederate States of America on February 28, 1861 and March 6, 1861. By May 8, a provision authorizing enlistments for war was enacted, and by August 8, 1861 the Confederate States, after being invaded [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] [11] and attacked by the United States of America, called for 400,000 volunteers to serve for one or three years. By April 1862, the Confederate States of America found it necessary to pass a conscription act, which drafted men into PACS.

The Confederate military leadership included many veterans from the United States Army and United States Navy who had resigned their Federal commissions and had won appointment to senior positions in the Confederate armed forces. Many had served in the Mexican-American War (including Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis), but others had little or no military experience (such as Leonidas Polk, who had attended West Point.) The Confederate officer corps was composed in part of young men from slave-owning families, but many came from non-owners. The Confederacy appointed junior and field grade officers by election from the enlisted ranks. Although no Army service academy was established for the Confederacy, many colleges of the South (such as The Citadel and Virginia Military Institute) maintained cadet corps that were seen as a training ground for Confederate military leadership. A naval academy was established at Drewry’s Bluff, Virginia[12] in 1863, but no midshipmen had graduated by the time the Confederacy collapsed.

The soldiers of the Confederate armed forces consisted mainly of white males with an average age between sixteen and twenty-eight.[citation needed] The Confederacy adopted conscription in 1862. Many thousands of slaves served as laborers, cooks, and pioneers. Some freed blacks and men of color served in local state militia units of the Confederacy, primarily in Louisiana and South Carolina, but their officers deployed them for "local defense, not combat."[13] Depleted by casualties and desertions, the military suffered chronic manpower shortages. In the spring of 1865 the Confederate Congress, influenced by the public support by General Lee, approved the recruitment of black infantry units. Contrary to Lee’s and Davis’ recommendations, the Congress refused “to guarantee the freedom of black volunteers.” No more than two hundred troops were ever raised.[14]

Military leaders

Military leaders of the Confederacy (with their state or country of birth and highest rank[15]) included:

- Robert E. Lee (Virginia) - General and General-in-Chief (1865)

- Albert Sidney Johnston (Kentucky) - General

- Joseph E. Johnston (Virginia) - General

- Braxton Bragg (North Carolina) - General

- P.G.T. Beauregard (Louisiana) - General

- Richard S. Ewell (Virginia) - Lieutenant General

- James Longstreet (South Carolina) - Lieutenant General

- Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson (Virginia)- Lieutenant General

- George Edward Pickett (Virginia) - General

- John Hunt Morgan (Kentucky) - Brigadier General

- A.P. Hill (Virginia) - Lieutenant General

- John Bell Hood (Kentucky) - Lieutenant General

- Wade Hampton III (South Carolina) - Lieutenant General

- Nathan Bedford Forrest (Tennessee) - Lieutenant General

- John Singleton Mosby, the "Grey Ghost of the Confederacy" (Virginia) - Colonel

- J.E.B. Stuart (Virginia) - Major General

- Edward Porter Alexander (Georgia) - Brigadier General

- Franklin Buchanan (Maryland) - Admiral

- Raphael Semmes (Maryland) - Rear Admiral (Brigadier General)

- Josiah Tattnall (Georgia) - Commodore

- Stand Watie (Georgia) - Brigadier General (last to surrender)

- Leonidas Polk (North Carolina) - Lieutenant General

- Sterling Price (Virginia) - Major General

- Jubal Anderson Early (Virginia) - Lieutenant General

- Richard Taylor (Kentucky) - Lieutenant General (Son of U.S. President Zachary Taylor)

- Lloyd J. Beall (South Carolina) - Colonel - Commandant of the Confederate States Marine Corps

- William Lamb (Virginia) - Colonel - Commandant of Fort Fisher

- Stephen Dodson Ramseur (North Carolina) Major General

- Camille Armand Jules Marie, Prince de Polignac (France) Major General

- John Austin Wharton (Tennessee) Major General

- Thomas L. Rosser (Virginia) Major General

- Patrick Cleburne (Ireland) Brigadier General

- Heros von Borcke (prussia) Lieutenant Colonel

For more details on this topic, see History of Confederate States Army Generals.African Americans in the Confederate Military

Main article: Military history of African Americans in the U.S. Civil War"Nearly 40% of the Confederacy's population were unfree ... the work required to sustain the same society during war naturally fell disproportionately on black shoulders as well. By drawing so many white men into the army, indeed, the war multiplied the importance of the black work force."[16] Even Georgia's Governor Joseph E. Brown noted that "the country and the army are mainly dependent upon slave labor for support." [17] Slave labor was used in a wide variety of support roles, from infrastructure and mining, to teamster and medical roles such as hospital attendants and nurses.[18]

The idea of arming slaves for use as soldiers was speculated on from the onset of the war, but not seriously considered by Davis or others in his administration.[19] Though an acrimonious and controversial debate was raised by a letter from Patrick Cleburne[20] urging the Confederacy to raise black soldiers by offering emancipation, it wouldn't be until Robert E. Lee wrote the Confederate Congress urging them that the idea would take serious traction. On March 13, 1865, the Confederate Congress passed General Order 14, and President Davis signed the order into law. The order was issued March 23, but only a few black companies were raised. Two companies were armed and drilled in the streets of Richmond, Virginia, shortly before the besieged southern capital fell.

Supply

Much like the Continental Army in the American Revolution, state governments were supposed to supply their soldiers. The supply situation for most Confederate Armies was dismal even when victorious. The lack of central authority and effective transportation infrastructure, especially the railroads, combined the frequent unwillingness or inability of Southern state governments to provide adequate funding, were key factors in the Army's demise. Individual commanders had to "beg, borrow or steal" food and ammunition from whatever sources were available, including captured Union depots and encampments, and private citizens regardless of their loyalties. Lee's campaign against Gettysburg and southern Pennsylvania (a rich agricultural region) was driven in part by his desperate need of supplies, namely food. Not surprisingly, in addition to slowing the Confederate advance such foraging aroused anger in the North and led many Northerners to support General Sherman's total warfare tactics as retaliation. Scorched earth policies especially in Georgia, South Carolina and the Virginian Shenandoah Valley proved far more devastating than anything Pennsylvania had suffered and further reduced the capacity of the increasingly effectively blockaded Confederacy to feed even its civilian population, let alone its Army. At many points during the war, and especially near the end, Confederate Armies were described as starving and, indeed, many died from lack of food and related illnesses. Towards more desperate stages of the war, the lack of food became a principal driving force for desertion.

Uniforms

See article :Uniforms of the Confederate Military

The Uniforms of the Confederate States military forces were the uniforms used by the Confederate Army and Navy during the American Civil War from 1861 to 1865. The uniform varied greatly due to a variety of reasons, such as location, limitations on the supply of cloth and other materials, and the cost of materials during the war.

Confederate forces were often poorly supplied with uniforms, especially late in the conflict. Servicemen sometimes wore combinations of uniform pieces combined with captured Union uniforms and items of personal clothing. They sometimes went without shoes altogether, and broad felt or straw hats were worn as often as kepis or naval caps.

Statistics

Total Servicemembers - 1,050,000 (Exact number is unknown. Posted figure is median of estimated range from 600,000 – 1,500,000)

Battle Deaths (Death figures are based on incomplete returns) - 74,524

Other Deaths (In Theater) - 59,297

Died in Union prisons - 26,000 to 31,000

Non-mortal Woundings - Unknown

At the end of the war 174,223 men surrendered to the Union Army.[21]

See also

- Conclusion of the American Civil War

- List of Confederate Regular Army officers

- Confederate Government Civil War units

- Confederate Air Force

References

- ^ Eicher, pg. 23

- ^ Sharf, pp.769-772

- ^ Johnson, p.19

- ^ Henderson, p.83

- ^ Abraham Lincoln and the American Civil War, accessed Oct 13, 2008

- ^ Evans, Vol III, p.38

- ^ DiLorenzo, p.257

- ^ DiLorenzo, p.135

- ^ Johnston (1961), p.19

- ^ George B. McClellan, accessed Oct 15, 2008

- ^ Stonewall Jackson, accessed Oct 13, 2008

- ^ 1862blackCSN

- ^ Rubin pg. 104

- ^ Levine pg. 146-147

- ^ Eicher, Civil War High Commands

- ^ Levine, Confederate Emancipation. pg 62

- ^ Journal of the Senate at an Extra Session of the General Assembly of the State of Georgia,, Convened under the Proclamation of the Governor, March 25th, 1863, p. 6

- ^ Levine, Confederate Emancipation p.62-63

- ^ ibid. p. 17-18

- ^ Official Records, Series I, Vol. LII, Part 2, pp. 586-92.

- ^ http://www1.va.gov/opa/fact/amwars.asp

External links

- A brief history of American Civil War

- The McGavock Confederate Cemetery at Franklin, TN

- Confederate offices Index of Politicians by Office Held or Sought

- Civil War Research & Discussion Group -*Confederate States of Am. Army and Navy Uniforms, 1861

- The Countryman, 1862-1866, published weekly by Turnwold, Ga., edited by J.A. Turner

- The Federal and the Confederate Constitution Compared

- The Making of the Confederate Constitution, by A. L. Hull, 1905.

- Confederate Currency

- Photographs of the original Confederate Constitution and other Civil War documents owned by the Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library at the University of Georgia Libraries.

- Photographic History of the Civil War, 10 vols., 1912.

- DocSouth: Documenting the American South - numerous online text, image, and audio collections.

- Confederate States of America: A Register of Its Records in the Library of Congress

- Confederate and State Uniform Regulations

Categories:- Military history of the Confederate States of America

- Confederate States Army - The Confederate States Army (CS Army) the land-based military operations. The CS Army was established in two phases with provisional and permanent organizations, which existed concurrently.

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.