- Culture of the United States

-

Enthusiastic crowds at the inaugural running of the United States Grand Prix at Indianapolis

Enthusiastic crowds at the inaugural running of the United States Grand Prix at IndianapolisThe Culture of the United States is a Western culture, having been originally influenced by European cultures. It has been developing since long before the United States became a country with its own unique social and cultural characteristics such as dialect, music, arts, social habits, cuisine, and folklore. Today, the United States of America is an ethnically and racially diverse country as a result of large-scale immigration from many different countries throughout its history.[1]

Its chief early influences came from English and Irish settlers of colonial America. British culture, due to colonial ties with Britain that spread the English language, legal system and other cultural inheritances, had a formative influence. Other important influences came from other parts of western Europe, especially Germany, France, and Italy.[citation needed]

Original elements also play a strong role, such as the invention of Jeffersonian Democracy.[2] Thomas Jefferson's Notes on the State of Virginia was perhaps the first influential domestic cultural critique by an American and a reactionary piece to the prevailing European consensus that America's domestic originality was degenerate.[2] Prevalent ideas and ideals which evolved domestically such as national holidays, uniquely American sports, military tradition, and innovations in the arts and entertainment give a strong sense of national pride among the population as a whole.[citation needed]

American culture includes both conservative and liberal elements, military and scientific competitiveness, political structures, risk taking and free expression, materialist and moral elements. Despite certain consistent ideological principles (e.g. individualism, egalitarianism, and faith in freedom and democracy), American culture has a variety of expressions due to its geographical scale and demographic diversity. The flexibility of U.S. culture and its highly symbolic nature lead some researchers to categorize American culture as a mythic identity;[3] others see it as American exceptionalism.

It also includes elements which evolved from Native Americans, and other ethnic subcultures; most prominently the culture of African Americans and different cultures from Latin America. Many cultural elements, especially popular culture, have been exported across the globe through modern mass media.

The United States has often been thought of as a melting pot, but recent developments tend towards cultural diversity, pluralism and the image of a salad bowl rather than a melting pot.[4][5] Due to the extent of American culture there are many integrated but unique social subcultures within the United States. The cultural affiliations an individual in the United States may have commonly depend on social class, political orientation and a multitude of demographic characteristics such as religious background, occupation and ethnic group membership.[1]

Culture of the

United StatesLanguages

Main article: Languages in the United StatesSee also: Language education in the United StatesAlthough the United States has no official language at the federal level, 30 states have passed legislation making English the official language and it is considered to be the de facto national language. According to the 2000 U.S. Census, more than 97% of Americans can speak English well, and for 81% it is the only language spoken at home. There are more than 300 languages besides English which can claim native speakers in the United States—some of which are spoken by the indigenous peoples (about 150 living languages) and others which were imported by immigrants.

Spanish has official status in the commonwealth of Puerto Rico and the state of New Mexico; Spanish is the primary spoken language in Puerto Rico and various smaller linguistic enclaves.[6] According to the 2000 census, there are nearly 30 million native speakers of Spanish in the United States. Bilingual speakers may use both English and Spanish reasonably well but code-switch according to their dialog partner or context. Some refer to this phenomenon as Spanglish.

Indigenous languages of the United States include the Native American languages, which are spoken on the country’s numerous Indian reservations and Native American cultural events such as pow wows; Hawaiian, which has official status in the state of Hawaii; Chamorro, which has official status in the commonwealths of Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands; Carolinian, which has official status in the commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands; and Samoan, which has official status in the commonwealth of American Samoa. American Sign Language, used mainly by the deaf, is also native to the country.

The national dialect is known as American English. There are four major regional dialects in the United States: northeastern, south, inland north, and midwestern. The Midwestern accent (considered the "standard accent" in the United States, and analogous in some respects to the received pronunciation elsewhere in the English-speaking world) extends from what were once the "Middle Colonies" across the Midwest to the Pacific states.[citation needed]

Native language statistics for the United States

The following information is an estimation as actual statistics constantly vary.

According to the CIA,[7] the following is the percentage of total population's native languages in the United States:

- English (82.1%)

- Spanish (10.7%)

- Other Indo-European languages (3.8%)

- Other Asian or Pacific Islander languages (2.7%)

- Other languages (0.7%)

Religion

Main article: Religion in the United States Completed in 1716, Mission Nuestra Señora de la Purísima Concepción de Acuña is one of numerous surviving colonial Spanish missions in the United States. These were primarily used to convert the Native Americans to Roman Catholicism.

Completed in 1716, Mission Nuestra Señora de la Purísima Concepción de Acuña is one of numerous surviving colonial Spanish missions in the United States. These were primarily used to convert the Native Americans to Roman Catholicism.

Surrounded by sleek modern skyscrapers, Saint Patrick's Cathedral stands as the last holdout of New York's Rockefeller Plaza

Surrounded by sleek modern skyscrapers, Saint Patrick's Cathedral stands as the last holdout of New York's Rockefeller Plaza

Among developed countries, the U.S. is one of the most religious (primarily Christian) in terms of its demographics. According to a 2002 study by the Pew Global Attitudes Project, the U.S. was the only developed nation in the survey where a majority of citizens reported that religion played a "very important" role in their lives, an attitude similar to that found in its neighbors in Latin America.[8] Today, governments at the national, state, and local levels are secular institution, with what is often called the "separation of church and state" prevailing. But like federal politics, the topic of religion in the United States can cause an emotionally heated debate over moral, ethical and legal issues affecting Americans of all faithes in everyday life, such as polarizing issues of abortion, gay marriage and what is considered obscenity.[citation needed]

Several of the original Thirteen Colonies were established by English and Irish settlers who wished to practice their own religion without discrimination or persecution: Pennsylvania was established by Quakers, Maryland by Roman Catholics and the Massachusetts Bay Colony by Puritans. The first bible printed in a European language in the Colonies was by German immigrant Christopher Sauer.[9] Nine of the thirteen colonies had official public religions. Yet by the time of the Philadelphia Convention of 1787, the United States became one of the first countries in the world to codify freedom of religion into law, although this originally applied only to the federal government, and not to state governments or their political subdivisions.[citation needed]

Modeling the provisions concerning religion within the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, the framers of the United States Constitution rejected any religious test for office, and the First Amendment specifically denied the central government any power to enact any law respecting either an establishment of religion, or prohibiting its free exercise. In following decades, the animating spirit behind the constitution's Establishment Clause led to the disestablishment of the official religions within the member states. The framers were mainly influenced by secular, Enlightenment ideals, but they also considered the pragmatic concerns of minority religious groups who did not want to be under the power or influence of a state religion that did not represent them.[10] Thomas Jefferson, author of the Declaration of Independence said "The priest has been hostile to liberty. He is always in alliance with the despot."[11]

Religious statistics for the United States

It should be noted the following information is an estimation as actual statistics constantly vary.

According to the CIA,[12] the following is the percentage of followers of different religions in the United States:

- Christian: (80.2%)

- Protestant (51.3%)

- Roman Catholic (23.9%)

- Mormon (1.7%)

- Other Christian (1.6%)

- Jewish (1.7%)

- Buddhist (0.7%)

- Muslim (0.6%)

- Other/Unspecified (2.5%)

- Unaffiliated (12.1%)

- None (4%)

Education

Main articles: Education in the United States and Educational attainment in the United StatesEducation in the United States is provided mainly by government, with control and funding coming from three levels: federal, state, and local. School attendance is mandatory and nearly universal at the elementary and high school levels (often known outside the United States as the primary and secondary levels).[citation needed]

Students have the options of having their education held in public schools, private schools, or home school. In most public and private schools, education is divided into three levels: elementary school, junior high school (also often called middle school), and high school. In almost all schools at these levels, children are divided by age groups into grades. Post-secondary education, better known as "college" or "university" in the United States, is generally governed separately from the elementary and high school system.

In the year 2000, there were 76.6 million students enrolled in schools from kindergarten through graduate schools. Of these, 72 percent aged 12 to 17 were judged academically "on track" for their age (enrolled in school at or above grade level). Of those enrolled in compulsory education, 5.2 million (10.4 percent) were attending private schools. Among the country's adult population, over 85 percent have completed high school and 27 percent have received a bachelor's degree or higher.[citation needed]

Race and ancestry

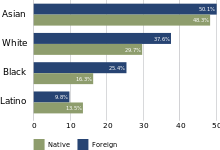

Main article: Race in the United StatesRace in the United States is based on physical characteristics and skin color and has played an essential part in shaping American society even before the nation's conception.[1] Until the civil rights movement of the 1960s, racial minorities in the United States faced discrimination and social as well as economic marginalization.[13] Today the U.S. Department of Commerce's Bureau of the Census recognizes four races, Native American or American Indian, African American, Asian and White (European American). According to the U.S. government, Hispanic Americans do not constitute a race, but rather an ethnic group. During the 2000 U.S. Census Whites made up 75.1% of the population with those being Hispanic or Latino constituting the nation's prevalent minority with 12.5% of the population. African Americans made up 12.3% of the total population, 3.6% were Asian American and 0.7% were Native American.[14]

The Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was ratified on December 6, 1865 which abolished slavery in the United States. The northern states had outlawed slavery in their territory in the late 18th and early 19th century although their industrial economies relied on the raw materials produced by slaves. Following the Reconstruction period in the 1870s, an apartheid regulation emerged in the Southern states named the Jim Crow laws that provided for legal segregation. Lynching was practiced throughout the U.S., including in the Northern states, until the 1930s, while continuing well into the civil rights movement in the South.[13] Chinese Americans were earlier marginalized as well during a significant proportion of U.S. history. Between 1882 and 1943 the United States instituted the Chinese Exclusion Act barring Chinese immigrants from entering the U.S. During the second world war roughly 120,000 Japanese Americans, 62% of whom were U.S. citizens,[15] were imprisoned in Japanese internment camps by the U.S. government following the attacks on Pearl Harbor, an American Military Base, by Japanese troops. Hispanic Americans also used to face segregation and other forms of discrimination. Although not proscribed by the law, they were regularly subject to second class citizen status.

Due to exclusion from or marginalization by earlier mainstream society, there emerged a unique sub-culture among the racial minorities in the United States. During the 1920s, Harlem, New York became home to the Harlem Renaissance. Music styles such as Jazz, Blues and Rap, Rock and roll as well as numerous folk-songs such as Blue Tail Fly (Jimmy Crack Corn) originated within the realms of African American culture, and was later on adopted by the mainstream.[13] Chinatowns can be found in many cities across the country and Asian cuisine has become a common staple in mainstream America. The Hispanic community has also had a dramatic impact on American culture. Today, Catholics are the largest religious denomination in the United States and out-number Protestants in the South-west and California.[16] Mariachi music and Mexican cuisine are commonly found throughout the Southwest, with some Latin dishes, such as burritos and tacos, found anywhere in the nation.

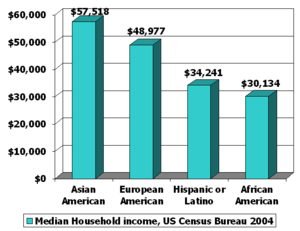

Economic variance and substantive segregation, is commonplace in the United States. Asian Americans have median household income and educational attainment exceeding that of other races. African Americans, Hispanics and Native Americans have considerably lower income and education than do White Americans.[17][18] In 2005 the median household income of Whites was 62.5% higher than that of African American, nearly one-quarter of whom live below the poverty line.[17] 46.9% of homicide victims in the United States are African American.[13][19]

According to a study,[citation needed] the mainstream media in American culture perpetuated,[citation needed] that black features are less attractive or desirable than white features. The concept that blackness was ugly degraded African Americans, manifesting itself as internalized racism.[20] In the 1960s, the Black is Beautiful cultural movement sought to dispel this notion.[21]

After the attacks by Muslim terrorists, on September 11, discrimination against Arabs and Muslims in the U.S. had risen significantly. The American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee (ADC) reported an increase in hate speech, cases of airline discrimination, hate crimes, police misconduct as well as racial profiling.[22] The USA PATRIOT Act, signed into effect by President Bush on October 26, 2001, has also raised concerns for violating civil liberties. Section 412 of the act provides the government with "sweeping new powers to detain foreign nationals and immigrants indefinitely with little or no due process at the discretion of the Attorney General."[22] Other sections also allow the government to conduct secret searches, seizures, and surveillance, and to freely interpret the definition of "terrorist activities".[citation needed]

Literature

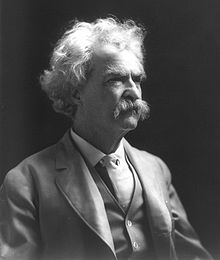

Mark Twain is regarded as among the greatest writers in American history.

Mark Twain is regarded as among the greatest writers in American history. Main article: Literature of the United States

Main article: Literature of the United StatesThe right to freedom of expression in the American constitution can be traced to German immigrant John Peter Zenger and his legal fight to make truthful publications in the Colonies a protected legal right, ultimately paving the way for the protected rights of American authors.[23][24]

In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, American art and literature took most of its cues from Europe. During its early history, America was a series of British colonies on the eastern coast of the present-day United States. Therefore, its literary tradition begins as linked to the broader tradition of English literature. However, unique American characteristics and the breadth of its production usually now cause it to be considered a separate path and tradition.[citation needed]

Writers such as Nathaniel Hawthorne, Edgar Allan Poe, and Henry David Thoreau established a distinctive American literary voice by the middle of the nineteenth century. Mark Twain and poet Walt Whitman were major figures in the century's second half; Emily Dickinson, virtually unknown during her lifetime, would be recognized as America's other essential poet. Eleven U.S. citizens have won the Nobel Prize in Literature, most recently Toni Morrison in 1993. Ernest Hemingway, the 1954 Nobel laureate, is often named as one of the most influential writers of the twentieth century.[25]

A work seen as capturing fundamental aspects of the national experience and character—such as Herman Melville's Moby-Dick (1851), Twain's The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1885), and F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby (1925)—may be dubbed the "Great American Novel". Popular literary genres such as the Western and hardboiled crime fiction were developed in the United States.

National Holidays

Fireworks light up the sky over the Washington Monument. Americans traditionally shoot fireworks throughout the night on the Fourth of July.

Fireworks light up the sky over the Washington Monument. Americans traditionally shoot fireworks throughout the night on the Fourth of July.

Martin Luther King Day memorializes the legacy of Dr. King, who is often regarded as the patriarch of the Civil Rights Movement. Dr. King is pictured above delivering his "I Have a Dream" speech.

Martin Luther King Day memorializes the legacy of Dr. King, who is often regarded as the patriarch of the Civil Rights Movement. Dr. King is pictured above delivering his "I Have a Dream" speech.

Inauguration Day is the only Federal holiday that is not annual but rather occurs only once every four years. The day begins with the inauguration ceremony and ends with a military parade.

Inauguration Day is the only Federal holiday that is not annual but rather occurs only once every four years. The day begins with the inauguration ceremony and ends with a military parade.

Halloween is often observed in the United States. It typically involves dressing up in costumes and an emphasis on the bizarre and frightening.

Halloween is often observed in the United States. It typically involves dressing up in costumes and an emphasis on the bizarre and frightening.

The United States observes holidays derived from events in American history, religious traditions, and national patriarchs.

Thanksgiving has become a traditional American holiday which evolved from the custom of English pilgrims to “give thanks” for their welfare. Today, Thanksgiving is generally celebrated as a family reunion with a large afternoon feast. European colonization has led to many traditional Christian holidays such as Easter, Lent, St. Patrick’s Day, and Christmas to be observed albeit celebrated in a secular manner by many Americans today.

Independence Day (colloquially known as the Fourth of July) celebrates the anniversary of the country’s Declaration of Independence from Great Britain. It is generally observed by parades throughout the day and the shooting of fireworks at night.

Halloween is thought to have evolved from the ancient Celtic festival of Samhain which was introduced in the American colonies by Irish settlers. It has become a holiday that is celebrated by children and teens who traditionally dress up in costumes and go door to door trick-or-treating for candy. It also brings about an emphasis on eerie and frightening urban legends and movies. The celebration of Halloween has become continuously popular among university students in the U.S. Both University of Wisconsin-Madison and Ohio University in Athens, Ohio are known across the country for their Halloween street fairs.[citation needed]

Additionally, Mardi Gras, which evolved from the Catholic tradition of Carnival, is observed notably in New Orleans, St. Louis, and Mobile, Alabama as well as numerous other towns.

Federally recognized holidays are as follows:

Date Official Name Remarks January 1 New Year's Day Celebrates beginning of the Gregorian calendar year. Festivities include counting down to midnight (12:00 am) on the preceding night, New Year's Eve. Traditional end of holiday season. Third Monday in January Birthday of Martin Luther King, Jr., or Martin Luther King, Jr. Day Honors Martin Luther King, Jr., Civil Rights leader, who was actually born on January 15, 1929; combined with other holidays in several states. First January 20 following a Presidential election Inauguration Day Observed only by federal government employees in Washington D.C., and the border counties of Maryland and Virginia, in order to relieve the traffic congestion that occurs with this major event. Swearing-in of President of the United States and Vice President of the United States. Celebrated every fourth year. Note: Takes place on January 21 if the 20th is a Sunday (although the President is still privately inaugurated on the 20th). If Inauguration Day falls on a Saturday or a Sunday, the preceding Friday or following Monday is not a Federal Holiday Third Monday in February Washington's Birthday Washington's Birthday was first declared a federal holiday by an 1879 act of Congress. The Uniform Holidays Act, 1968, shifted the date of the commemoration of Washington's Birthday from February 22 to the third Monday in February. Many people now refer to this holiday as "Presidents' Day" and consider it a day honoring all American presidents. However, neither the Uniform Holidays Act nor any subsequent law changed the name of the holiday from Washington's Birthday to Presidents' Day.[26] Last Monday in May Memorial Day Honors the nation's war dead from the Civil War onwards; marks the unofficial beginning of the summer season. (traditionally May 30, shifted by the Uniform Holidays Act 1968) July 4 Independence Day Celebrates Declaration of Independence, also called the Fourth of July. First Monday in September Labor Day Celebrates the achievements of workers and the labor movement; marks the unofficial end of the summer season. Second Monday in October Columbus Day Honors Christopher Columbus, traditional discoverer of the Americas. In some areas it is also a celebration of Italian culture and heritage. (traditionally October 12); celebrated as American Indian Heritage Day and Fraternal Day in Alabama;[27] celebrated as Native American Day in South Dakota.[28] In Hawaii, it is celebrated as Discoverer's Day, though is not an official state holiday.[29] November 11 Veterans Day Honors all veterans of the United States armed forces. A traditional observation is a moment of silence at 11:00 am remembering those killed in war. (Commemorates the 1918 armistice, which began at "the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month.") Fourth Thursday in November Thanksgiving Day Traditionally celebrates the giving of thanks for the autumn harvest. Traditionally includes the consumption of a turkey dinner. Traditional start of the holiday season. December 25 Christmas Celebrates the Nativity of Jesus. Some people consider aspects of this religious holiday, such as giving gifts and decorating a Christmas tree, to be secular rather than explicitly Christian. - Federal Holidays Calendars[30] from the U.S. Office of Personnel Management.

Cuisine

Main article: Cuisine of the United StatesThe cuisine of the United States is extremely diverse, owing to the vastness of the continent, the relatively large population (1/3 of a billion people) and the number of native and immigrant influences. Mainstream American culinary arts are similar to those in other Western countries. Wheat is the primary cereal grain. Traditional American cuisine uses ingredients such as turkey, white-tailed deer venison, potatoes, sweet potatoes, corn, squash, and maple syrup, indigenous foods employed by American Indians and early European settlers. Slow-cooked pork and beef barbecue, crab cakes, potato chips, cotton candy and chocolate chip cookies are distinctively American styles.[citation needed]

The types of food served at home vary greatly and depend upon the region of the country and the family's own cultural heritage. Recent immigrants tend to eat food similar to that of their country of origin, and Americanized versions of these cultural foods, such as American Chinese cuisine or Italian-American cuisine often eventually appear; an example is Vietnamese cuisine, Korean cuisine and Thai cuisine. German cuisine has a profound impact on American cuisine, especially mid-western cuisine, with potatoes, noodles, roasts, stews and cakes/pastries being the most iconic ingredients in both cuisines.[5] Dishes such as the hamburger, pot roast, baked ham and hot dogs are examples of American dishes derived from German cuisine.[31][32] Different regions of the United States have their own cuisine and styles of cooking. The state of Louisiana, for example, is known for its Cajun and Creole cooking. Cajun and Creole cooking are influenced by French, Acadian, and Haitian cooking, although the dishes themselves are original and unique. Examples include Crawfish Etouffee, Red Beans and Rice, Seafood or Chicken Gumbo, Jambalaya, and Boudin. Italian, German, Hungarian and Chinese influences, traditional Native American, Caribbean, Mexican and Greek dishes have also diffused into the general American repertoire. It is not uncommon for a "middle class" family from "middle America" to eat, for example, restaurant pizza, home-made pizza, enchiladas con carne, chicken paprikas, beef stroganof and bratwurst with sauerkraut for dinner throughout a single week.

Soul food, developed by African slaves, is popular around the South and among many African Americans elsewhere. Syncretic cuisines such as Louisiana creole, Cajun, Pennsylvania Dutch, and Tex-Mex are regionally important. Iconic American dishes such as apple pie, fried chicken, pizza, hamburgers, and hot dogs derive from the recipes of various immigrants and domestic innovations. So-called French fries, Mexican dishes such as burritos and tacos, and pasta dishes freely adapted from Italian sources are consumed.[33]

Americans generally prefer coffee to tea, with more than half the adult population drinking at least one cup a day.[34] Marketing by U.S. industries is largely responsible for making orange juice and milk (now often fat-reduced) ubiquitous breakfast beverages.[35] During the 1980s and 1990s, Americans' caloric intake rose 24%;[33] frequent dining at fast food outlets is associated with what health officials call the American "obesity epidemic." Highly sweetened soft drinks are popular; sugared beverages account for 9% of the average American's daily caloric intake.[36]

Representative American Foods

-

Traditional Thanksgiving dinner with Turkey, dressing, sweet potatoes, and cranberry sauce.

-

A cream-based New England chowder, traditionally made with potatoes and clams.

-

A Caesar salad containing croutons, parmesan cheese, lemon juice, olive oil, Worcestershire, and pepper.

-

Creole Jambalaya with shrimp, ham, tomato, and Andouille sausage.

-

Chicken Fried Steak (alternatively known as Country Fried Steak.)

-

A submarine sandwich which includes a variety of Italian luncheon meats.

-

A hot dog sausage topped with beef chili, white onions and mustard.

-

A meatloaf with a tomato sauce topping.

Social class and work

Main article: Social class in the United StatesThough most Americans today identify themselves as middle class, American society and its culture are considerably fragmented.[1][37][38] Social class, generally described as a combination of educational attainment, income and occupational prestige, is one of the greatest cultural influences in America.[1] Nearly all cultural aspects of mundane interactions and consumer behavior in the U.S. are guided by a person's location within the country's social structure.

Distinct lifestyles, consumption patterns and values are associated with different classes. Early sociologist-economist Thorstein Veblen, for example, noted that those at the very top of the social ladder engage in conspicuous leisure as well as conspicuous consumption. Upper middle class persons commonly identify education and being cultured as prime values. Persons in this particular social class tend to speak in a more direct manner that projects authority, knowledge and thus credibility. They often tend to engage in the consumption of so-called mass luxuries, such as designer label clothing. A strong preference for natural materials and organic foods as well as a strong health consciousness tend to be prominent features of the upper middle class. Middle class individuals in general value expanding one's horizon, partially because they are more educated and can afford greater leisure and travels. Working class individuals take great pride in doing what they consider to be "real work," and keep very close-knit kin networks that serve as a safeguard against frequent economic instability.[1][38][39] Working class Americans as well as many of those in the middle class may also face occupation alienation. In contrast to upper middle class professionals who are mostly hired to conceptualize, supervise and share their thoughts, many Americans have little autonomy or creative latitude in the workplace.[40] As a result white collar professionals tend to be significantly more satisfied with their work.[1][40] More recently those in the center of the income strata, who may still identify as middle class, have faced increasing economic insecurity,[41] supporting the idea of a working class majority.[39]

Political behavior is affected by class; more affluent individuals are more likely to vote, and education and income affect whether individuals tend to vote for the Democratic or Republican party. Income also had a significant impact on health as those with higher incomes had better access to health care facilities, higher life expectancy, lower infant mortality rate and increased health consciousness.[citation needed] This is particularly noticeable with black voters who are often socially conservative, yet overwhelmingly vote Democratic.[42][43][44]

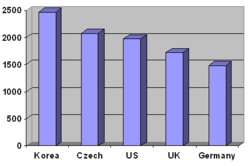

In the United States occupation is one of the prime factors of social class and is closely linked to an individual’s identity. The average work week in the U.S. for those employed full-time was 42.9 hours long with 30% of the population working more than 40 hours a week.[46] The Average American worker earned $16.64 an hour in the first two quarters of 2006.[47] Overall Americans worked more than their counterparts in other developed post-industrial nations. While the average worker in Denmark enjoyed 30 days of vacation annually, the average American had 16 annual vacation days.[48] In 2000 the average American worked 1,978 hours per year, 500 hours more than the average German, yet 100 hours less than the average Czech. Overall the U.S. labor force was the most productive in the world (overall, not by hour worked), largely due to its workers working more than those in any other post-industrial country (excluding South Korea).[45] Americans generally hold working and being productive in high regard; being busy as and working extensively may also serve as the means to obtain esteem.[39]

Housing

Immediately after World War II, Americans began living in increasing numbers in the suburbs, belts around major cities with higher density than rural areas, but much lower than urban areas. This move has been attributed to many factors such as the automobile, the availability of large tracts of land, the convenience of more and longer paved roads, the increasing violence in urban centers (see white flight), and the cheapness of housing. These new single-family houses were usually one or two stories tall, and often were part of large contracts of homes built by a single developer. The resulting low-density development has been given the pejorative label "urban sprawl." This is changing, however. "White flight" is reversing, with many Yuppies and upper-middle-class, empty nest Baby Boomers returning to urban living, usually in condominiums, such as in New York City's Lower East Side, and Chicago's South Loop. The result has been the displacement of many poorer, inner-city residents. (see gentrification). American cities with housing prices near the national median have also been losing the middle income neighborhoods, those with median income between 80% and 120% of the metropolitan area's median household income. Here, the more affluent members of the middle class, who are also often referred to as being professional or upper middle class, have left in search of larger homes in more exclusive suburbs. This trend is largely attributed to the so called "Middle class squeeze," which has caused a starker distinction between the statistical middle class and the more privileged members of the middle class.[49] In more expensive areas such as California, however, another trend has been taking place where an influx of more affluent middle class households has displaced those in the actual middle of society and converted former middle-middle class neighborhoods into upper middle class neighborhoods.[49]

The population of rural areas has been declining over time as more and more people migrate to cities for work and entertainment. The great exodus from the farms came in the 1940s; in recent years fewer than 2% of the population lives on farms (though others live in the countryside and commute to work). Electricity and telephone, and sometimes cable and Internet services are available to all but the most remote regions. As in the cities, children attend school up to and including high school and only help with farming during the summer months or after school.[citation needed]

About half of Americans now live in what is known as the suburbs. The suburban nuclear family has been identified as part of the "American dream": a married couple with children owning a house in the suburbs. This archetype is reinforced by mass media, religious practices, and government policies and is based on traditions from Anglo-Saxon cultures. One of the biggest differences in suburban living as compared to urban living is the housing occupied by the families. The suburbs are filled with single-family homes separated from retail districts, industrial areas, and sometimes even public schools. However, many American suburbs are incorporating these districts on smaller scales, attracting more people to these communities.

Housing in urban areas may include more apartments and semi-attached homes than in the suburbs or small towns. Aside from housing, the major difference from suburban living is the density and diversity of many different subcultures, as well as retail and manufacturing buildings mixed with housing in urban areas.

Technology, gadgets, and automobiles

Further information: United States technological and industrial history and Passenger vehicles in the United StatesAmericans, by and large, are often fascinated by new technology and new gadgets. There are many within the United States that share the attitude that through technology, many of the evils in the society can be solved.[citation needed] Many of the new technological innovations in the modern world were either first invented in the United States and/or first widely adopted by Americans. Examples include: the lightbulb, the airplane, the transistor, nuclear power, the personal computer, video games and online shopping, as well as the development of the Internet.

Automobiles play a large role in American culture, whether it is in the lives of private individuals or in the areas of arts and entertainment. The rise of suburbs and the need for workers to commute to cities brought about the popularization of automobiles. In 2001, 90% of Americans drove to work in cars.[50] Lower energy and land costs favor the production of relatively large, powerful cars. The culture in the 1950s and 1960s often catered to the automobile with motels and drive-in restaurants. Americans tend to view obtaining a driver's license as a rite of passage. Outside of relatively few urban areas, it is considered a necessity for most Americans to own and drive cars. New York City is the only locality in the United States where more than half of all households do not own a car.[50]

Race relations

Main Articles: Racism, Race relations in the United States and Race in the United States.

The origins of racism and inequality dates back to slavery, as Afro-Americans are mostly descendants of African slaves imported to the Americas, including the USA. Slavery was partially abolished by the Emancipation Proclamation issued by president Abraham Lincoln in 1862 for slaves in the Southeastern United States during the Civil War and the defeat of the secessionist Confederate States of America. Slavery was rendered illegal by the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Jim Crow Laws prevented full use of citizenship until the 20th century. The Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed official or legal segregation in public places or limited access to minorities. A large majority of Americans of all races disapprove of racism. Nevertheless, some Americans whom self-identify themselves white, black, Latino, Asian, American Indian, and Pacific Islander, continue to hold negative racial/ethnic stereotypes about each other based on a social group of people they belong to.

Gender relations

Courtship, cohabitation, and adolescent sexuality

Main article: Adolescent sexuality in the United StatesCouples often meet through religious institutions, work, school, or friends. "Dating services," services that are geared to assist people in finding partners, are popular both on and offline. The trend over the past few decades has been for more and more couples deciding to cohabit before, or instead of, getting married. The 2000 Census reported 9.7 million different-sex partners living together and about 1.3 million same-sex partners living together. Some states now have domestic partner statutes and judge-made palimony doctrines that confer some legal support for unmarried couples.[citation needed]

Adolescent sex is common; in 2010 most Americans first had intercourse in their late teens.[51] While few teens have had sex at age 15, by age 18 slightly more than half of females and nearly two-thirds of males have had intercourse.[52] More than half of sexually active teens have had sexual partners they were dating.[53][54] Risky sexual behaviors that involve "anything intercourse related" are "rampant" among teenagers.[55] Teen pregnancies in the United States decreased 28% between 1990 and 2000 from 117 pregnancies per every 1,000 teens to 84 per 1,000.[56] The U.S. is rated, based on 2002 numbers, 84 out of 170 countries based on teenage fertility rate, according to the World Health Organization.[57]

In 2006, approximately one out of every four sexually active person 15–24, had contracted a sexually transmitted disease each year, particularly pappilomavirus, Trichomoniasis, and chlamydia .[58]

Marriage and divorce

Main articles: Marriage in the United States and Divorce in the United StatesSee also: Cohabitation in the United StatesMarriage laws are established by individual states. Same-sex marriage is currently legal in New York, Massachusetts, Iowa, Vermont, Maine, New Hampshire, Connecticut, and Washington D.C.. New Jersey, California, Oregon, Washington, and Nevada allow same-sex couples access to most state-level marriage benefits with civil unions or domestic partnerships; Hawaii, Maryland, Illinois, Wisconsin and Colorado offer some benefits to couples in domestic partnerships. The typical wedding involves a couple proclaiming their commitment to one another in front of their close relatives and friends, often presided over by a religious figure such as a minister, priest, or rabbi, depending upon the faith of the couple. In traditional Christian ceremonies, the bride's father will "give away" (hand off) the bride to the groom. Secular weddings are also common, often presided over by a judge, Justice of the Peace, or other municipal official.

Divorce is the province of state governments, so divorce law varies from state to state. Prior to the 1970s, divorcing spouses had to allege that the other spouse was guilty of a crime or sin like abandonment or adultery; when spouses simply could not get along, lawyers were forced to manufacture "uncontested" divorces. The no-fault divorce revolution began in 1969 in California; South Dakota was the last state to allow no-fault divorce, in 1985. No-fault divorce on the grounds of "irreconcilable differences" is now available in all states. However, many states have recently required separation periods prior to a formal divorce decree. State law provides for child support where children are involved, and sometimes for alimony. "Married adults now divorce two-and-a-half times as often as adults did 20 years ago and four times as often as they did 50 years ago... between 40% and 60% of new marriages will eventually end in divorce. The probability within... the first five years is 20%, and the probability of its ending within the first 10 years is 33%... Perhaps 25% of children ages 16 and under live with a stepparent."[59] The median length for a marriage in the U.S. today is 11 years with 90% of all divorces being settled out of court.

Gender roles

Since the 1970s, traditional gender roles of male and female have been increasingly challenged by both legal and social means. Today, there are far fewer roles that are legally restricted by one's sex. The military remains a notable exception, where women may not be put into direct combat by law. Asymmetrical warfare, however, has put women into situations which are direct combat operations in all but name.[citation needed]

Most social roles are not gender-restricted by law, though there are still cultural inhibitions surrounding certain roles. More and more women have entered the workplace, and in the year 2000 made up 46.6% of the labor force, up from 18.3% in 1900. Most men, however, have not taken up the traditional full-time homemaker role; likewise, few men have taken traditionally feminine jobs such as receptionist or nurse (although nursing was traditionally a male role before the American Civil War).[citation needed]

Death rituals

It is customary for Americans to hold a wake in a funeral home within a couple days of the death of a loved one. The body of the deceased may be embalmed and dressed in fine clothing if there will be an open-casket viewing. Traditional Jewish and Muslim practice include a ritual bath and no embalming. Friends, relatives and acquaintances gather, often from distant parts of the country, to "pay their last respects" to the deceased. Flowers are brought to the coffin and sometimes eulogies, elegies, personal anecdotes or group prayers are recited. Otherwise, the attendees sit, stand or kneel in quiet contemplation or prayer. Kissing the corpse on the forehead is typical among Italian Americans[60] and others. Condolences are also offered to the widow or widower and other close relatives.

A funeral may be held immediately afterwards or the next day. The funeral ceremony varies according to religion and culture. American Catholics typically hold a funeral mass in a church, which sometimes takes the form of a Requiem mass. Jewish Americans may hold a service in a synagogue or temple. Pallbearers carry the coffin of the deceased to the hearse, which then proceeds in a procession to the place of final repose, usually a cemetery. The unique Jazz funeral of New Orleans features joyous and raucous music and dancing during the procession.

Mount Auburn Cemetery (founded in 1831) is known as "America's first garden cemetery."[61] American cemeteries created since are distinctive for their park-like setting. Rows of graves are covered by lawns and are interspersed with trees and flowers. Headstones, mausoleums, statuary or simple plaques typically mark off the individual graves. Cremation is another common practice in the United States, though it is frowned upon by various religions. The ashes of the deceased are usually placed in an urn, which may be kept in a private house, or they are interred. Sometimes the ashes are released into the atmosphere. The "sprinkling" or "scattering" of the ashes may be part of an informal ceremony, often taking place at a scenic natural feature (a cliff, lake or mountain) that was favored by the deceased.

A so-called death industry has developed in the United States that has replaced earlier, more informal traditions. Before the popularity of funeral homes, people usually held wakes in private houses.[citation needed]

Household arrangements

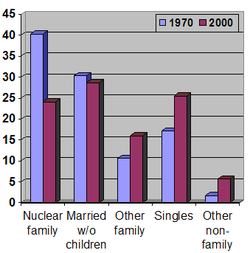

Further information: American family structure American family structure has no particular household arrangement being prevalent enough to be identified as the average.[62]

American family structure has no particular household arrangement being prevalent enough to be identified as the average.[62]

Today, family arrangements in the United States reflect the diverse and dynamic nature of contemporary American society. Although for a relatively brief period of time in the 20th century most families adhered to the nuclear family concept (two-married adults with a biological child), single-parent families, childless/childfree couples, and fused families now constitute the majority of families.[citation needed]

Most Americans will marry and get divorced at least once during their life; thus, most individuals will live in a variety of family arrangements. A person may grow up in a single-parent family, go on to marry and live in childless couple arrangement, then get divorced, live as a single for a couple of years, re-marry, have children and live in a nuclear family arrangement.[1][62]

"The nuclear family... is the idealized version of what most people think when they think of "family..." The old definition of what a family is... the nuclear family- no longer seems adequate to cover the wide diversity of household arrangements we see today, according to many social scientists (Edwards 1991; Stacey 1996). Thus has arisen the term postmodern family, which is meant to describe the great variability in family forms, including single-parent families and child-free couples."- Brian K. Williams, Stacey C. Sawyer, Carl M. Wahlstrom, Marriages, Families & Intinamte Relationships, 2005.[62]

Other changes to the landscape of American family arrangements include dual-income earner households and delayed independence among American youths. Whereas most families in the 1950s and 1960s relied on one income earner, most commonly the husband, the vast majority of family households now have two-income earners.[citation needed]

Another change is the increasing age at which young Americans leave their parental home. Traditionally, a person past "college age" who lived with their parent(s) was viewed negatively, but today it is not uncommon for children to live with their parents until their mid-twenties. This trend can be mostly attributed to rising living costs that far exceed those in decades past. Thus, many young adults now remain with their parents well past their mid-20s. This topic was a cover article of TIME magazine in 2005.[citation needed]

Exceptions to the custom of leaving home in one's mid-20s can occur especially among Italian and Hispanic Americans, and in expensive urban real estate markets such as New York City,[63] California,[64] and Honolulu,[65] where monthly rents commonly exceed $1000 a month.

Year Families (69.7%) Non-families (31.2%) Married couples (52.5%) Single Parents Other blood relatives Singles (25.5%) Other non-family Nuclear family Without children Male Female 2000 24.1% 28.7% 9.9% 7% 10.7% 14.8% 5.7% 1970 40.3% 30.3% 5.2% 5.5% 5.6% 11.5% 1.7% Single-parent households are households consisting of a single adult (most often a woman) and one or more children. In the single-parent household, one parent typically raises the children with little to no help from the other. This parent is the sole "breadwinner" of the family and thus these households are particularly vulnerable economically. They have higher rates of poverty, and children of these households are more likely to have educational problems.[citation needed]

Regional variations

Semi-distinct cultural regions of the United States include New England, the Mid-Atlantic States, the Southern United States, the Midwestern United States and the Western United States-an area that can be further subdivided, on the basis of the local culture into the Pacific States and the Mountain States.

The western coast of the continental U.S. consisting of California, Oregon, and the state of Washington is also sometimes referred to as the Left Coast, indicating its left-leaning political orientation and tendency towards liberal norms, folkways and values.

Southern United States are informally called "the Bible Belt" due to socially conservative evangelical Protestantism which is a significant part of the region's culture and Christian church attendance across the denominations is generally higher their than the nation's average. This region is usually contrasted with the mainline Protestantism and Catholicism of the northeastern United States, the religiously diverse Midwest and Great Lakes, the Mormon Corridor in Utah and southern Idaho, and the relatively secular western United States. The percentage of non-religious people is the highest in the northeastern state of Vermont at 34%, compared to the Bible Belt state of Alabama, where it is 6%.[66]

Strong cultural differences have a long history in the U.S. with the southern slave society in the antebellum period serving as a prime example. Not only social, but also economic tensions between the Northern and Southern states were so severe that they eventually caused the South to declare itself an independent nation, the Confederate States of America; thus provoking the American civil war.[13] One example of regional variations is the attitude towards the discussion of sex, often sexual discussions would have less restrictions in the Northeastern United States, but yet is seen as taboo in the Southern United States.

In his 1989 book, "Albion's Seed" (ISBN 0195069056), David Hackett Fischer makes a strong case for the theory that the United States is made up today of four distinct regional cultures. The book's focus is on the folkways of four groups of settlers from the British Isles that emigrated from distinct regions of Britain and Ireland to the British American colonies during the 17th and 18th centuries. Fischer's thesis is that the culture and folkways of each of these groups persisted, albeit with some modification over time, providing the basis for the four modern regional cultures of the United States.

According to Fischer, the foundation of American culture was formed from four mass migrations from four different regions of the British Isles by four distinct socio-religious groups. New England's earliest settlement period occurred between 1629 and 1640 when Puritans, mostly from East Anglia in England, settled there, forming the New England regional culture. The next mass migration was of southern English cavaliers and their Irish and Scottish domestic servants to the Chesapeake Bay region between 1640 and 1675. This facilitated the development of the Southern American culture. Then, between 1675 and 1725, thousands of Irish, English and German Quakers, led by William Penn, settled in the Delaware Valley. This settlement resulted in the formation of what is today considered the "General American" culture, although, according to Fischer, it is really just a regional American culture, even if it does today encompass most of the U.S. from the mid-Atlantic states to the Pacific Coast. Finally, Irish, Scottish and English settlers from the borderlands of Britain and Ireland migrated to Appalachia between 1717 and 1775. They formed the regional culture of the Upland South, which has since spread west to such areas as West Texas and parts of the U.S. Southwest.

Fischer suggests that the U.S. today is not a country with one General American culture and three or more regional sub-cultures. He asserts that the country is composed of just regional cultures, and that understanding that helps one to understand many things about modern American life. Fischer also makes the point that the development of these regional cultures derived not only from where exactly the settlers first came, but when they came. Fischer asserts that during different periods to time, a population of people will have very distinct beliefs, fears, hopes and prejudices, and that various groups of settlers brought these feelings to the New World where they more or less froze in time in America, even if they eventually changed in their place of origin.

Drugs and Alcohol

"Just Say No" paraphernalia at the Reagan Library display

"Just Say No" paraphernalia at the Reagan Library display Further information: History of United States drug prohibition

Further information: History of United States drug prohibitionAmerican attitudes towards drugs and alcoholic beverages have evolved considerably throughout the country's history. In the 19th century, alcohol was readily available and consumed, and no laws restricted the use of other drugs. Attitudes on drug addiction started to change, resulting in the Harrison Act which eventually became proscriptive.

A movement to ban alcoholic beverages, called the Temperance movement, emerged in the late 19th century. Several American Protestant religious groups, as well as women's groups such as the Women's Christian Temperance Union, supported the movement. In 1919, Prohibitionists succeeded in amending the Constitution to prohibit the sale of alcohol. Although the Prohibition period did result in lowering alcohol consumption overall, banning alcohol outright proved to be unworkable, as the previously legitimate distillery industry was replaced by criminal gangs which trafficked in alcohol. Prohibition was repealed in 1931. States and localities retained the right to remain "dry", and to this day, a handful still do.

During the Vietnam War era, attitudes swung well away from prohibition. Commentators noted that an 18 year old could be drafted to war but could not buy a beer.

Since 1980, the trend has been toward greater restrictions on alcohol and drug use. The focus this time, however, has been to criminalize behaviors associated with alcohol, rather than attempt to prohibit consumption outright. New York was the first state to enact tough drunk-driving laws in 1980; since then all other states have followed suit. A "Just Say No to Drugs" movement replaced the more libertine ethos of the 1960s. As a result, since the late half of the 1980s to about the year 2000, all states made the legal drinking age (to purchase alcoholic beverages) at 21.[citation needed]

Sports

Main article: Sports in the United StatesA typical Baseball diamond as seen from the stadium. Traditionally the game is played for nine innings but can be prolonged if there is a tie.

The opening of College football season is a major part of American culture and tradition. Massive marching bands accompanied by cheerleaders and colorguard are almost universal at American Football games, especially during halftime. Although high school bands tend to be much smaller, it is rare for a game not to feature a marching band at halftime.

The opening of College football season is a major part of American culture and tradition. Massive marching bands accompanied by cheerleaders and colorguard are almost universal at American Football games, especially during halftime. Although high school bands tend to be much smaller, it is rare for a game not to feature a marching band at halftime. Bowling is a popular pastime for Americans of all ages.

Bowling is a popular pastime for Americans of all ages.

Baseball is the oldest of the major American team sports. Professional baseball dates from 1869 and had no close rivals in popularity until the 1960s. Though baseball is no longer the most popular sport,[67] it is still referred to as the "national pastime". Also unlike the professional levels of the other popular spectator sports in the U.S., Major League Baseball teams play almost every day from April to October. American football, known in the United States as simply football, now attracts more television viewers than baseball, however, the National Football League season lasts from September to December, ending with the playoffs and Super Bowl in January and February.

Basketball is another major sport, represented professionally by the National Basketball Association. It was invented in Springfield, Massachusetts 1891, by Canadian-born physical education teacher James Naismith. College basketball is also popular thanks in large part to the NCAA Tournament in March, also known as March Madness.

Football, known in many anglophone countries as American Football, is considered to be the most popular sport in the United States.[68] The 32-team National Football League (NFL) is the most popular professional American football league. Its championship game, the Super Bowl has often been the highest rated television show, with an audience of over 100 million viewers annually.[citation needed]

Ice hockey is the fourth leading professional team sport. Always a mainstay of Great Lakes and New England-area culture, the sport gained tenuous footholds in regions like the American South since the early 1990s, as the National Hockey League pursued a policy of expansion.[69]

College football throughout the autumn months, and basketball also attract audiences of millions. Some communities, particularly in rural areas, place great emphasis on their local high school football team. American football games usually include cheerleaders and marching bands which aim to raise school spirit and entertain the crowd at half-time.

Boxing and horse racing were once[when?] the most watched individual sports, but they have been eclipsed by golf and auto racing, particularly NASCAR.[citation needed] Tennis and many outdoor sports are also popular.

What is known in the rest of the world as "football" is called soccer in the United States. Though not a leading professional sport, it is played widely at the youth and amateur levels. A recent addition as an American pastime, it gained popularity in the later half of the twentieth century. The creation of professional leagues such as MLS, and the success of US national teams has fueled its growth to sport that is now widely played throughout all age groups.

Sports and community culture

Homecoming is an annual tradition of the United States. People, towns, high schools and colleges come together, usually in late September or early October, to welcome back former residents and alumni. It is built around a central event, such as a banquet, a parade, and most often, a game of American football, or, on occasion, basketball, or ice hockey. When celebrated by schools, the activities vary. However, they usually consist of a football game played on the school's home football field, activities for students and alumni, a parade featuring the school's marching band and sports teams, and the coronation of a Homecoming Queen.

Science and technology

Further information: Science and technology in the United States The Washington Post on Monday, July 21, 1969 stating "'The Eagle Has Landed'—Two Men Walk on the Moon".

The Washington Post on Monday, July 21, 1969 stating "'The Eagle Has Landed'—Two Men Walk on the Moon".

There is a fondness for scientific advancement and technological innovation in American culture, resulting in the flow of many modern innovations. The great American inventors include Robert Fulton (the steamboat); Samuel Morse (the telegraph); Eli Whitney (the cotton gin, interchangeable parts); Cyrus McCormick (the reaper); and Thomas Alva Edison (with more than a thousand inventions credited to his name).

This propensity for application of scientific ideas continued throughout the 20th century with innovations that held strong international benefits. The twentieth century saw the arrival of the Space Age, the Information Age, and a renaissance in the health sciences. This culminated in cultural milestones such as the Apollo moon landings, the creation of the Personal Computer, and the sequencing effort called the Human Genome Project.

Throughout its history, American culture has made significant gains through the open immigration of accomplished scientists. Accomplished scientists include: Scottish scientist Alexander Graham Bell, who developed and patented the telephone and many other inventions in 1872; German scientist Charles Steinmetz, who developed new alternating-current electrical systems in 1889; Russian scientist Vladimir Zworykin, who invented the motion camera in 1919; Serb scientist Nikola Tesla who invented the brushless electrical motor based on rotating magnetic fields in 1884. With the rise of the Nazi party in Germany, a large number of scientists fled Germany and immigrated to the country, one of them being theoretical physicist Albert Einstein in the year 1933.

In the years during and following WWII, several innovative scientists immigrated to the U.S. from Europe, such as Enrico Fermi, who came from Italy in 1938 and led the work that produced the world's first self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction. Post-war Europe saw many of its scientists, such as rocket scientist Wernher von Braun, recruited by the United States as part of Operation Paperclip.

Visual arts

Main article: Visual arts of the United States Armory Show in New York City, 1913

Armory Show in New York City, 1913

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, American artists primarily painted landscapes and portraits in a realistic style. A parallel development taking shape in rural America was the American craft movement, which began as a reaction to the Industrial Revolution. Developments in modern art in Europe came to America from exhibitions in New York City such as the Armory Show in 1913. After World War II, New York emerged as a center of the art world.[citation needed] Painting in the United States today covers a vast range of styles.

Architecture

Main article: Architecture of the United StatesArchitecture in the United States is regionally diverse and has been shaped by many external forces, not only English. U.S. architecture can therefore be said to be eclectic, something unsurprising in such a multicultural society.[70] In the absence of a single large-scale architectural influence from indigenous peoples such as those in Mexico or Peru, generations of designers have incorporated influences from around the world. Currently, the overriding theme of American Architecture is modernity: an example of which are the skyscrapers of the 20th century.

Early Neoclassicism accompanied the Founding Father's idealization of European Enlightenment, making it the predominant architectural style for public buildings and large manors. However, in recent years, the suburbanization and mass migration to the Sun Belt has allowed architecture to reflect a Mediterranean style as well.[citation needed]

Sculpture

Main article: Sculpture of the United StatesThe history of sculpture in the United States reflects the country's 18th century foundation in Roman republican civic values as well as Protestant Christianity.[citation needed]

Popular culture

Ray Browne, a leading scholar of American studies, said "Popular culture is the way of life in which and by which most people in any society live. In a democracy like the United States, it is the voice of the people."[71]

Fashion

An "aloha shirt," popular in Hawaii and temperate western states Main article: Fashion in the United States

Main article: Fashion in the United StatesApart from professional business attire, fashion in the United States is eclectic and predominantly informal. While Americans' diverse cultural roots are reflected in their clothing, particularly those of recent immigrants, cowboy hats and boots and leather motorcycle jackets are emblematic of specifically American styles. Blue jeans were popularized as work clothes in the 1850s by merchant Levi Strauss, a German immigrant in San Francisco, and adopted by many American teenagers a century later. They are worn in every state by people of all ages and social classes. Along with mass-marketed informal wear in general, blue jeans are arguably U.S. culture's primary contribution to global fashion.[72]

Theater

Main article: Theater in the United StatesTheater of the United States is based in the Western tradition.[citation needed]

Film and television

Main articles: Television in the United States and Cinema of the United StatesThe cinema and television are major mass media in the United States.

Music

Main article: Music in the United StatesAmerican music can be heard all over the world.

Dance

Main article: Dance in the United StatesThere is great variety in dance in the United States.

Volunteerism

De Tocqueville first noted, in 1835, the American attitude towards helping others in need. A 2010 Charities Aid Foundation study found that Americans were the fifth most willing to donate time and money in the world at 55%.[73]

Group affiliations

The Knights of Columbus exhibiting their group identity.

The Knights of Columbus exhibiting their group identity.

As the United States is a diverse nation, it is home to numerous organization and social groups and individuals may derive their group affiliated identity from a variety of sources. Many Americans, especially white collar professionals belong to professional organizations such as the APA, ASA or ATFLC, although books like Bowling Alone indicate that Americans affiliate with these sorts of groups less often than they did in the 1950s and 1960s. Today, Americans derive a great deal of their identity through their work and professional affiliation, especially among individuals higher on the economic ladder. Recently professional identification has led to many clerical and low-level employees giving their occupations new, more respectable titles, such as "Sanitation service engineer" instead of "Janitor."[1]

Additionally many Americans belong to non-profit organizations and religious establishments and may volunteer their services to such organizations. The Rotary Club, the Knights of Columbus or even the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals are examples of such non-profit and mostly volunteer-run organizations. Ethnicity plays another important role in providing some Americans with group identity,[13] especially among those who recently immigrated.[5] Many American cities are home to ethnic enclaves such as a Chinatown and Little Italies remain in some cities. Local patriotism may be also provide group identity. For example, a person may be particularly proud to be from California or New York City, and may display clothing from local sports team.

Political lobbies such as the AARP, ADL, NAACP, NOW and GLAAD (examples being civil rights activist organizations) not only provide individuals with a sentiment of intra-group allegiance but also increase their political representation in the nation's political system. Combined, profession, ethnicity, religious, and other group affiliations have provided Americans with a multitude of options from which to derive their group based identity.[1]

Firearms

Main article: Gun politics in the United StatesMain article: Gun culture Navy Junior ROTC cadets from Hamilton High School, Ohio, practice marksmanship at the Fire Arms Training Simulator at the Naval Station Great Lakes.

Navy Junior ROTC cadets from Hamilton High School, Ohio, practice marksmanship at the Fire Arms Training Simulator at the Naval Station Great Lakes.

In contrast to many other developed nations, firearms laws in the United States are permissive and private gun ownership is common, with about 40% of households containing at least one firearm. In fact, there are more privately-owned firearms in the United States than in any other country, both per capita and in total.[74] Rates of gun ownership vary significantly by region and by state, with gun ownership most common in Alaska, the Plains States, the Mountain States, and the South, and least prevalent in Hawaii, the island territories, and the Northeast megalopolis.[75] Hunting, plinking and target shooting are popular pastimes, although ownership of firearms for purely utilitarian purposes such as self-defense is common as well. Ownership of handguns, while not uncommon, is less common than ownership of long guns. Gun ownership is more prevalent among men than among women, with men being approximately four times more likely than women to report owning a gun.[76]

Views on justice and the death penalty

Further information: Capital punishment in the United StatesCapital punishment has often been a contentious social issue in the United States; while historically, a large majority of the American public has favored it in cases of murder, the extent of this support has varied over time, and there has long been strong opposition from some sectors of the population. While public support today is substantially lower than it was in the 1980s and '90s (in 1994 it reached an all-time high of 80%), it has been largely static over the past decade.[77] 65% of Americans believe the death penalty is justified, although support is lower when respondents are given a choice of the death penalty or life imprisonment with no possibility of parole.[78] 50% of those cited appeal to fairness, or revenge, as being their reason for supporting the death penalty and 11% cited deterrence as a motivation. 29% were opposed to the death penalty.[79]

Capital punishment can be used in the U.S. for capital crimes in some states. Currently the use of the death penalty is determined mostly by individual states. As of March 2011, the following U.S. states have fully abolished the death penalty: Alaska, Hawaii, Illinois, Iowa, Maine, Michigan, Minnesota, New Jersey, New Mexico, North Dakota, Rhode Island, Vermont, West Virginia and Wisconsin.

Other aspects

America is one of a few countries that does not primarily use the metric system; though many products are dual-labelled, the United States customary units system is dominant.

See also

- America 24/7 (book)

- American dream

- American middle class

- Americana

- Body contact and personal space in the United States

- Broadway theatre

- Culture of the Southern United States

- Folklore of the United States

- Etiquette in the United States

- Philanthropy in the United States

- Protestant work ethic

- Work and Travel USA (organization)

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Thompson, William; Joseph Hickey (2005). Society in Focus. Boston, MA: Pearson. ISBN 0-205-41365-X.

- ^ a b "Mr. Jefferson and the giant moose: natural history in early America", Lee Alan Dugatkin. University of Chicago Press, 2009. ISBN 0226169146, 9780226169149. University of Chicago Press, 2009. Chapter x.

- ^ McDonald, James (2010) Interplay:Communication, Memory, and Media in the United States. Goettingen: Cuvillier, p. 120. ISBN 3-86955-322-7.

- ^ Clack, George, et al. (September 1997). "Chapter 1". One from Many, Portrait of the USA. United States Information Agency. http://usinfo.state.gov/usa/infousa/facts/factover/ch1.htm.

- ^ a b c Adams, J.Q.; Pearlie Strother-Adams (2001). Dealing with Diversity. Chicago, IL: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company. ISBN 0-7872-8145-X.

- ^ "Selected Social Characteristics in the United States: 2007". United States Census Bureau. http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/ADPTable?_bm=y&-geo_id=01000US&-qr_name=ACS_2007_1YR_G00_DP2&-context=adp&-ds_name=ACS_2007_1YR_G00_&-tree_id=306&-_lang=en&-redoLog=false&-format=-. Retrieved 2008-10-09.

- ^ United States, CIA World Factbook.

- ^ "U.S. Stands Alone in its Embrace of Religion". Pew Global Attitudes Project. http://pewglobal.org/reports/display.php?ReportID=167. Retrieved January 1, 2007.

- ^ "1795–1895. One hundred years of American commerce", Chauncey Mitchell Depew. D.O. Haynes, 1895. p. 309.

- ^ Marsden, George M. 1990. Religion and American Culture. Orlando: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, pp.45–46.

- ^ Jefferson, Thomas (1904). The writings of Thomas Jefferson. Thomas Jefferson Memorial Association of the United States. pp. 119.

- ^ "CIA Fact Book". CIA World Fact Book. 2002. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/us.html. Retrieved 2007-12-30.

- ^ a b c d e f Hine, Darlene; William C. Hine, Stanley Harrold (2006). The African American Odyssey. Boston, MA: Pearson. ISBN 0-12-182217-3.

- ^ "U.S. Census Bureau, Race and Hispanic or Latino during the 2000 Census". http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/QTTable?_bm=y&-geo_id=01000US&-qr_name=DEC_2000_SF1_U_QTP3&-ds_name=DEC_2000_SF1_U. Retrieved 2006-12-15.

- ^ Semiannual Report of the War Relocation Authority, for the period January 1 to June 30, 1946, not dated. Papers of Dillon S. Myer. Scanned image at trumanlibrary.org. Accessed September 18, 2006.

- ^ "Religion in the U.S. by state". USA Today. http://www.usatoday.com/graphics/news/gra/gnoreligion/flash.htm. Retrieved 2006-12-14.

- ^ a b "U.S. Census Bureau, Income newsbrief 2004". Archived from the original on 2006-12-11. http://web.archive.org/web/20061211105333/http://www.census.gov/Press-Release/www/releases/archives/income_wealth/005647.html. Retrieved 2006-12-15.

- ^ "U.S. Census Bureau, educational attainment in the U.S. 2003" (PDF). http://www.census.gov/prod/2004pubs/p20-550.pdf. Retrieved 2006-12-15.

- ^ "U.S. Department of Justice, Crime and Race". Archived from the original on 2006-12-12. http://web.archive.org/web/20061212100248/http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/homicide/race.htm. Retrieved 2006-12-15.

- ^ Key Issues in Postcolonial Feminism: A Western Perspective by Chris Weedon, Cardiff University

In her novel The Bluest Eye (1981), Toni Morrison depicts the effects of the legacy of 19th century racism for poor black people in the United States. The novel tells of how the daughter of a poor black family, Pecola Breedlove, internalizes white standards of beauty to the point where she goes mad. Her fervent wish for blue eyes comes to stand for her wish to escape the poor, unloving, racist environment in which she lives.

- ^ Some notes on the black cultural movement

- ^ a b ADC.org

- ^ "Famous American Trials: John Peter Zenger Trial 1735", Doug Linder. University of Missouri-Kansas City. 2001. Accessed September 9, 2010.

- ^ "American history told by contemporaries..., Volume 2", John Gould Curtis. The Macmillan company, 1919. p. 192.

- ^ Meyers, Jeffrey (1999). Hemingway: A Biography. New York: Da Capo, p. 139. ISBN 0-306-80890-0.

- ^ Law.cornell.edu

- ^ "Section 1-3-8". http://www.legislature.state.al.us/codeofalabama/1975/1-3-8.htm.

- ^ "Holidays Observed". http://www.state.sd.us/puc/misc/holidays.htm.

- ^ The.honoluluadvertiser.com

- ^ OPM.gov

- ^ "History of the hot dog". Archived from the original on 2006-10-18. http://web.archive.org/web/20061018070129/http://www.hot-dog.org/hd/hd_history.htm. Retrieved 2006-11-13.

- ^ "History of the Hamburger". http://www.ahamburgertoday.com/archives/2005/08/the_history_of.php. Retrieved 2006-11-13.

- ^ a b Klapthor, James N. (2003-08-23). "What, When, and Where Americans Eat in 2003". Institute of Food Technologists. http://www.ift.org/cms/?pid=1000496. Retrieved 2007-06-19.

- ^ "Coffee Today". Coffee Country. PBS. May 2003. http://www.pbs.org/frontlineworld/stories/guatemala.mexico/facts.html#02. Retrieved 2007-06-19.

- ^ Smith, Andrew F. (2004). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Food and Drink in America. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 131–32. ISBN 0-19-515437-1. Levenstein, Harvey (2003). Revolution at the Table: The Transformation of the American Diet. Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press, pp. 154–55. ISBN 0-520-23439-1. Pirovano, Tom (2007). "Health & Wellness Trends—The Speculation Is Over". AC Nielsen. http://us.acnielsen.com/pubs/2006_q1_ci_health.shtml. Retrieved 2007-06-12.

- ^ "Fast Food, Central Nervous System Insulin Resistance, and Obesity". Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. American Heart Association. 2005. http://atvb.ahajournals.org/cgi/content/full/25/12/2451#R3-101329. Retrieved 2007-06-09. "Let's Eat Out: Americans Weigh Taste, Convenience, and Nutrition" (PDF). U.S. Dept. of Agriculture. http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/eib19/eib19_reportsummary.pdf. Retrieved 2007-06-09.

- ^ "Middle class according to The Drum Major Institute for public policy". http://www.pbs.org/now/politics/middleclassoverview.html. Retrieved 2006-07-25.

- ^ a b Fussel, Paul (1983). Class: A Guide through the American Status System. New York, NY: Touchstone. ISBN 0-671-79225-3.

- ^ a b c Ehrenreich, Barbara (1989). Fear of Falling: The Inner Life of the Middle Class. New York, NY: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-0973331.