- Indo-European languages

-

"Indo-European" redirects here. For other uses, see Indo-European (disambiguation).See also: List of Indo-European languages

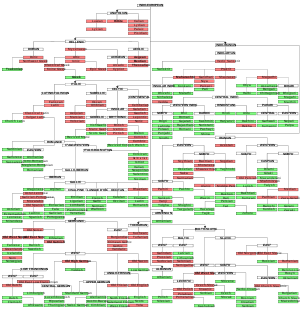

Indo-European Geographic

distribution:Before the 16th century, Europe, and South, Central and Southwest Asia; today worldwide. Linguistic classification: One of the world's major language families Proto-language: Proto-Indo-European Subdivisions: Anatolian (extinct)Hellenic (Greek)Tocharian (extinct)ISO 639-2 and 639-5: ine

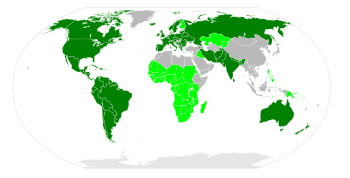

Countries with a majority of speakers of IE languagesCountries with an IE minority language with official statusThe Indo-European languages are a family (or phylum) of several hundred related languages and dialects,[1] including most major current languages of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and South Asia and also historically predominant in Anatolia. With written attestations appearing since the Bronze Age, in the form of the Anatolian languages and Mycenaean Greek, the Indo-European family is significant to the field of historical linguistics as possessing the longest recorded history after the Afroasiatic family.

Indo-European languages are spoken by almost three billion native speakers,[2] the largest number for any recognised language family. Of the twenty languages with the largest numbers of native speakers according to SIL Ethnologue, twelve are Indo-European: Spanish, English, Hindi, Portuguese, Bengali, Russian, German, Marathi, French, Italian, Punjabi, and Urdu, accounting for over 1.7 billion native speakers.[3] Several disputed proposals link Indo-European to other major language families.

Contents

History of Indo-European linguistics

Main article: Indo-European studiesSuggestions of similarities between Indian and European languages began to be made by European visitors to India in the 16th century. In 1583 Thomas Stephens, an English Jesuit missionary in Goa, noted similarities between Indian languages, specifically Konkani, and Greek and Latin. These observations were included in a letter to his brother which was not published until the twentieth century.[4]

The first account by a western European to mention the ancient language Sanskrit came from Filippo Sassetti (born in Florence, Italy in 1540), a merchant who traveled to the Indian subcontinent. Writing in 1585, he noted some word similarities between Sanskrit and Italian (these included devaḥ/dio "God", sarpaḥ/serpe "serpent", sapta/sette "seven", aṣṭa/otto "eight", nava/nove "nine").[4] However, neither Stephens' nor Sassetti's observations led to further scholarly inquiry.[4]

In 1647, Dutch linguist and scholar Marcus Zuerius van Boxhorn noted the similarity among Indo-European languages, and supposed that they derived from a primitive common language which he called "Scythian". He included in his hypothesis Dutch, Albanian, Greek, Latin, Persian, and German, later adding Slavic, Celtic and Baltic languages. However, Van Boxhorn's suggestions did not become widely known and did not stimulate further research.

Gaston Coeurdoux and others had made observations of the same type. Coeurdoux made a thorough comparison of Sanskrit, Latin and Greek conjugations in the late 1760s to suggest a relationship between them. Similarly, Mikhail Lomonosov compared different languages groups of the world including Slavic, Baltic ("Kurlandic"), Iranian ("Medic"), Finnish, Chinese, "Hottentot", and others. He emphatically expressed the antiquity of the linguistic stages accessible to comparative method in the drafts for his Russian Grammar (published 1755).[5]

The hypothesis reappeared in 1786 when Sir William Jones first lectured on the striking similarities between three of the oldest languages known in his time: Latin, Greek, and Sanskrit, to which he tentatively added Gothic, Celtic, and Old Persian,[6] though his classification contained some inaccuracies and omissions.[7][dead link]

It was Thomas Young who in 1813[8] first used the term Indo-European, which became the standard scientific term (except in Germany[9]) through the work of Franz Bopp, whose systematic comparison of these and other old languages supported the theory. Bopp's Comparative Grammar, appearing between 1833 and 1852, counts as the starting point of Indo-European studies as an academic discipline.

The classical phase of Indo-European comparative linguistics leads from Franz Bopp's Comparative Grammar (1833) to August Schleicher's 1861 Compendium and up to Karl Brugmann's Grundriss, published in the 1880s. Brugmann's junggrammatische reevaluation of the field and Ferdinand de Saussure's development of the laryngeal theory may be considered the beginning of "modern" Indo-European studies. The generation of Indo-Europeanists active in the last third of the 20th century (such as Calvert Watkins, Jochem Schindler and Helmut Rix) developed a better understanding of morphology and, in the wake of Kuryłowicz's 1956 Apophonie, understanding of the ablaut.

Classification

Further information: List of languages by first written accountsThe various subgroups of the Indo-European language family include ten major branches, given in the chronological order of their earliest surviving written attestations:

- Anatolian, the earliest attested branch. Isolated terms in Old Assyrian sources from the 19th century BC, Hittite texts from about the 16th century BC; extinct by Late Antiquity.

- Hellenic, fragmentary records in Mycenaean Greek from the late 15th to the early 14th century BC; Homeric texts date to the 8th century BC. (See Proto-Greek, History of the Greek.)

- Indo-Iranian, descended from Proto-Indo-Iranian (dated to the late 3rd millennium BC).

- Iranian, attested from roughly 1000 BC in the form of Avestan. Epigraphically from 520 BC in the form of Old Persian (Behistun inscription).

- Indo-Aryan or Indic languages, attested from the late 15th to the early 14th century BC in Mitanni texts showing traces of Indo-Aryan. Epigraphically from the 3rd century BC in the form of Prakrit (Edicts of Ashoka). The Rigveda is assumed to preserve intact records via oral tradition dating from about the mid-2nd millennium BC in the form of Vedic Sanskrit.

- Dardic

- Nuristani

- Italic, including Latin and its descendants (the Romance), attested from the 7th century BC.

- Celtic, descended from Proto-Celtic. Tartessian dated from 8th century BC,[10][11] Gaulish inscriptions date as early as the 6th century BC; Celtiberian from the 2nd century BC; Old Irish manuscript tradition from about the 8th century AD, and there are inscriptions in Old Welsh from the same period.

- Germanic (from Proto-Germanic), earliest testimonies in runic inscriptions from around the 2nd century AD, earliest coherent texts in Gothic, 4th century AD. Old English manuscript tradition from about the 8th century AD.

- Armenian, alphabet writings known from the beginning of the 5th century AD.

- Tocharian, extant in two dialects (Turfanian and Kuchean), attested from roughly the 6th to the 9th century AD. Marginalized by the Old Turkic Uyghur Khaganate and probably extinct by the 10th century.

- Balto-Slavic, believed by most Indo-Europeanists[12] to form a phylogenetic unit, while a minority ascribes similarities to prolonged language contact.

- Slavic (from Proto-Slavic), attested from the 9th century AD (possibly earlier; see Slavic runes), earliest texts in Old Church Slavonic.

- Baltic, attested from the 14th century AD; for languages attested that late, they retain unusually many archaic features attributed to Proto-Indo-European (PIE).

- Albanian, attested from the 14th century AD; Proto-Albanian likely emerged from Paleo-Balkan predecessors.[13][14]

In addition to the classical ten branches listed above, several extinct and little-known languages have existed:

- Illyrian — related to Messapian.

- Venetic — close to Italic and possibly Continental Celtic.

- Liburnian — apparently grouped with Venetic.

- Messapian — not conclusively deciphered.

- Phrygian — language of ancient Phrygia, possibly close to Thracian, Greek, and Armenian[citation needed].

- Paionian — extinct language once spoken north of Macedon.

- Thracian — possibly including Dacian.

- Dacian — possibly very close to Thracian.

- Ancient Macedonian — proposed relationships to Greek, Illyrian, Thracian, and Phrygian.

- Ligurian language — possibly not Indo-European; possibly close to or part of Celtic.

- Lusitanian — possibly related to (or part of) Celtic, or Ligurian, or Italic.

Grouping

Further information: Language familiesHypothetical

Indo-European

phylogenetic cladesMembership of these languages in the Indo-European language family is determined by genetic relationships, meaning that all members are presumed to be descendants of a common ancestor, Proto-Indo-European. Membership in the various branches, groups and subgroups or Indo-European is also genetic, but here the defining factors are shared innovations among various languages, suggesting a common ancestor that split off from other Indo-European groups. For example, what makes the Germanic languages a branch of Indo-European is that much of their structure and phonology can so be stated in rules that apply to all of them. Many of their common features are presumed to be innovations that took place in Proto-Germanic, the source of all the Germanic languages.

Tree versus wave model

See also: Language changeTo the evolutionary history of a language family, a genetic "tree model" is considered appropriate especially if communities do not remain in effective contact as their languages diverge. Exempted from this concept are shared innovations acquired by borrowing (or other means of convergence), that cannot be considered genetic. In this case the so-called "wave model" applies, featuring borrowings and no clear underlying genetic tree. It has been asserted, for example, that many of the more striking features shared by Italic languages (Latin, Oscan, Umbrian, etc.) might well be areal features. More certainly, very similar-looking alterations in the systems of long vowels in the West Germanic languages greatly postdate any possible notion of a proto-language innovation (and cannot readily be regarded as "areal", either, since English and continental West Germanic were not a linguistic area). In a similar vein, there are many similar innovations in Germanic and Balto-Slavic that are far more likely to be areal features than traceable to a common proto-language, such as the uniform development of a high vowel (*u in the case of Germanic, *i/u in the case of Baltic and Slavic) before the PIE syllabic resonants *ṛ,* ḷ, *ṃ, *ṇ, unique to these two groups among IE languages, which is in agreement with the wave model. The Balkan sprachbund even features areal convergence among members of very different branches.

Using an extension to the Ringe-Warnow model of language evolution, early IE was confirmed to have featured limited contact between distinct lineages, while only the Germanic subfamily exhibited a less treelike behaviour as it acquired some characteristics from neighbours early in its evolution rather than from its direct ancestors. The internal diversification of especially West Germanic is cited to have been radically non-treelike.[15]

Proposed subgroupings

Specialists have postulated the existence of such subfamilies (subgroups) as Italo-Celtic, Graeco-Armenian, Graeco-Aryan, and Germanic with Balto-Slavic. The vogue for such subgroups waxes and wanes; Italo-Celtic for example used to be a standard subgroup of Indo-European, but it is now little honored, in part because much of the evidence on which it was based has turned out to have been misinterpreted.[16]

Subgroupings of the Indo-European languages are commonly held to reflect genetic relationships and linguistic change. The generic differentiation of Proto-Indo-European into dialects and languages happened hand in hand with language contact and the spread of innovations over different territories.

Rather than being entirely genetic, the grouping of satem languages is commonly inferred as an innovative change that occurred just once, and subsequently spread over a large cohesive territory or PIE continuum that affected all but the peripheral areas.[17] Kortlandt proposes the ancestors of Balts and Slavs took part in satemization and were then drawn into the western Indo-European sphere.[18]

Shared features of Phrygian and Greek[19] and of Thracian and Armenian[20] group together with the Indo-Iranian family of Indo-European languages.[21] Some fundamental shared features, like the aorist (a verb form denoting action without reference to duration or completion) having the perfect active particle -s fixed to the stem, link this group closer to Anatolian languages[22] and Tocharian. Shared features with Balto-Slavic languages, on the other hand (especially present and preterit formations), might be due to later contacts.[23]

The Indo-Hittite hypothesis proposes the Indo-European language family to consist of two main branches: one represented by the Anatolian languages and another branch encompassing all other Indo-European languages. Features that separate Anatolian from all other branches of Indo-European (such as the gender or the verb system) have been interpreted alternately as archaic debris or as innovations due to prolonged isolation. Points proffered in favour of the Indo-Hittite hypothesis are the (non-universal) Indo-European agricultural terminology in Anatolia[24] and the preservation of laryngeals.[25] However, in general this hypothesis is considered to attribute too much weight to the Anatolian evidence. According to another view the Anatolian subgroup left the Indo-European parent language comparatively late, approximately at the same time as Indo-Iranian and later than the Greek or Armenian divisions. A third view, especially prevalent in the so-called French school of Indo-European studies, holds that extant similarities in non-satem languages in general - including Anatolian - might be due to their peripheral location in the Indo-European language area and early separation, rather than indicating a special ancestral relationship.[26] Hans J. Holm, based on lexical calculations, arrives at a picture roughly replicating the general scholarly opinion and refuting the Indo-Hittite hypothesis.[27]

Satem and centum languages

Main article: Centum-Satem isoglossThe division of the Indo-European languages into a Satem vs. a Centum group was devised by von Bradke in the late 19th century and is said by some[who?] to be outdated because of being based on just one phonological feature.

Suggested macrofamilies

Some linguists propose that Indo-European languages form part of a hypothetical Nostratic macrofamily, and attempt to relate Indo-European to other language families, such as South Caucasian, Uralic (the Indo-Uralic proposal), Dravidian, and Afroasiatic. This theory, like the similar Eurasiatic theory of Joseph Greenberg, and the Proto-Pontic postulation of John Colarusso, remains highly controversial, however, and is not accepted by most linguists in the field. Objections to such groupings are not based on any theoretical claim about the likely historical existence or non-existence of such macrofamilies; it is entirely reasonable to suppose that they might have existed. The serious difficulty lies in identifying the details of actual relationships between language families; it is very hard to find concrete evidence that transcends chance resemblance, or is not equally likely explained as being due to borrowing (including Wanderwörter, which can travel very long distances). Since the signal-to-noise ratio in historical linguistics declines steadily over time, at great enough time-depths it becomes open to reasonable doubt that it can even be possible to distinguish between signal and noise.

Evolution

Proto-Indo-European

Main article: Proto-Indo-European languageThe Proto-Indo-European language (PIE) is the common ancestor of the Indo-European languages, spoken by the Proto-Indo-Europeans. From the 1960s, knowledge of Anatolian became certain enough to establish its relationship to PIE. Using the method of internal reconstruction an earlier stage, called Pre-Proto-Indo-European, has been proposed.

PIE was an inflected language, in which the grammatical relationships between words were signaled through inflectional morphemes (usually endings). The roots of PIE are basic morphemes carrying a lexical meaning. By addition of suffixes, they form stems, and by addition of desinences (usually endings), these form grammatically inflected words (nouns or verbs). The hypothetical Indo-European verb system is complex and, like the noun, exhibits a system of ablaut.

Diversification

The diversification of the parent language into the attested branches of daughter languages is historically unattested. The timeline of the evolution of the various daughter languages, on the other hand, is mostly undisputed, quite regardless of the question of Indo-European origins.

- 2500 BC–2000 BC: The breakup into the proto-languages of the attested dialects is complete. Proto-Greek is spoken in the Balkans, Proto-Indo-Iranian north of the Caspian in the emerging Andronovo culture. The Bronze Age reaches Central Europe with the Beaker culture, likely composed of various Centum dialects. The Tarim mummies possibly correspond to proto-Tocharians.

- 2000 BC–1500 BC: Catacomb culture north of the Black Sea. The chariot is invented, leading to the split and rapid spread of Iranian and Indo-Aryan from the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex over much of Central Asia, Northern India, Iran and Eastern Anatolia. Proto-Anatolian is split into Hittite and Luwian. The pre-Proto-Celtic Unetice culture has an active metal industry (Nebra skydisk).

- 1500 BC–1000 BC: The Nordic Bronze Age develops pre-Proto-Germanic, and the (pre)-Proto-Celtic Urnfield and Hallstatt cultures emerge in Central Europe, introducing the Iron Age. Migration of the Proto-Italic speakers into the Italian peninsula (Bagnolo stele). Redaction of the Rigveda and rise of the Vedic civilization in the Punjab. The Mycenaean civilization gives way to the Greek Dark Ages.

- 1000 BC–500 BC: The Celtic languages spread over Central and Western Europe. Baltic languages are spoken in a huge area from present-day Poland to the Ural Mountains.[28] Proto Germanic. Homer and the beginning of Classical Antiquity. The Vedic Civilization gives way to the Mahajanapadas. Siddhartha Gautama preaches Buddhism. Zoroaster composes the Gathas, rise of the Achaemenid Empire, replacing the Elamites and Babylonia. Separation of Proto-Italic into Osco-Umbrian and Latin-Faliscan. Genesis of the Greek and Old Italic alphabets. A variety of Paleo-Balkan languages are spoken in Southern Europe.

- 500 BC–1 BC/AD: Classical Antiquity: spread of Greek and Latin throughout the Mediterranean, and during the Hellenistic period (Indo-Greeks) to Central Asia and the Hindukush. Kushan Empire, Mauryan Empire. Proto-Germanic. The Anatolian languages are extinct.

- 1 BC/AD 500: Late Antiquity, Gupta period; attestation of Armenian. Proto-Slavic. The Roman Empire and then the Migration period marginalize the Celtic languages to the British Isles.

- 500–1000: Early Middle Ages. The Viking Age forms an Old Norse koine spanning Scandinavia, the British Isles and Iceland. The Islamic conquest and the Turkic expansion results in the Arabization and Turkification of significant areas where Indo-European languages were spoken. Tocharian is extinct in the course of the Turkic expansion while Northeastern Iranian (Scytho-Sarmatian) is reduced to small refugia. Slavic languages spread over wide areas in eastern and southeastern Europe, largely replacing Romance in the Balkans (with the exception of Romanian) and whatever was left of the paleo-Balkan languages (with the exception of Albanian).

- 1000–1500: Late Middle Ages: Attestation of Albanian and Baltic.

- 1500–2000: Early Modern period to present: Colonialism results in the spread of Indo-European languages to every continent, most notably Romance (North, Central and South America, French Canada, North and Sub-Saharan Africa, West Asia), West Germanic (English in North America, Sub-Saharan Africa, East Asia and Australia; to a lesser extent Dutch and German), and Russian to Central Asia and North Asia.

Sound changes

Main article: Indo-European sound lawsAs the Proto-Indo-European language broke up, its sound system diverged as well, changing according to various sound laws evidenced in the daughter languages. Notable cases of such sound laws include Grimm's law in Proto-Germanic, loss of prevocalic *p- in Proto-Celtic, loss of intervocalic *s- in Proto-Greek, Brugmann's law in Proto-Indo-Iranian, as well as satemization (discussed above). Grassmann's law and Bartholomae's law may or may not have operated at the common Indo-European stage.

Comparison of conjugations

The following table presents a comparison of conjugations of the thematic present indicative of the verbal root *bʰer- of the English verb to bear and its reflexes in various early attested IE languages and their modern descendants or relatives, showing that all languages had in the early stage an inflectional verb system.

Proto-Indo-European

(*bʰer- 'to carry')I (1st. Sg.) *bʰéroh₂ You (2nd. Sg.) *bʰéresi He/She/It (3rd. Sg.) *bʰéreti We (1st. Du.) *bʰérowos You (2nd. Du.) *bʰéreth₁es They (3rd. Du.) *bʰéretes We (1st. Pl.) *bʰéromos You (2nd. Pl.) *bʰérete They (3rd. Pl.) *bʰéronti Major Subgroup Hellenic Indo-Iranian Italic Celtic Armenian Germanic Balto-Slavic Albanian Indo-Aryan Iranian Baltic Slavic Ancient Representative Ancient Greek Vedic Sanskrit Avestan Latin Old Irish Classical Arm. Gothic Old Prussian Old Church Sl. Old Albanian I (1st. Sg.) phérō bhárāmi ferō biru; berim berem baíra /bɛra/ berǫ You (2nd. Sg.) phéreis bhárasi fers biri; berir beres baíris bereši He/She/It (3rd. Sg.) phérei bhárati fert berid berē baíriþ beretъ We (1st. Du.) — bhárāvas — — — baíros berevě You (2nd. Du.) phéreton bhárathas — — — baírats bereta They (3rd. Du.) phéreton bháratas — — — — berete We (1st. Pl.) phéromen bhárāmas ferimus bermai beremk` baíram beremъ You (2nd. Pl.) phérete bháratha fertis beirthe berēk` baíriþ berete They (3rd. Pl.) phérousi bháranti ferunt berait beren baírand berǫtъ Modern Representative Modern Greek Hindi-Urdu Persian French Irish Armenian (Eastern; Western) German Lithuanian Czech Albanian I (1st. Sg.) férno (maiṃ) bharūṃ (mi)baram (je) {con}fère beirim berum em; g'perem (ich) {ge}bäre beru (unë) mbart You (2nd. Sg.) férnis (tū) bhare (mi)bari (tu) {con}fères beirir berum es; g'peres (du) {ge}bierst bereš (ti) mbart He/She/It (3rd. Sg.) férni (vah) bhare (mi)barad (il) {con}fère beireann; %beiridh berum ē; g'perē (sie) {ge}biert bere (ai/ajo) mbart We (1st. Pl.) férnoume (ham) bhareṃ (mi)barim (nous) {con}ferons beirimid; beiream berum enk`; g'perenk` (wir) {ge}bären berem(e) (ne) mbartim You (2nd. Pl.) férnete (tum) bharo (mi)barid (vous) {con}ferez beireann sibh; %beirthaoi berum ek`; g'perek` (ihr) {ge}bärt berete (ju) mbartni They (3rd. Pl.) férnoun (ve) bhareṃ (mi)barand (ils) {con}fèrent beirid berum en; g'peren (sie) {ge}bären berou (ata/ato) mbartin While similarities are still visible between the modern descendants and relatives of these ancient languages, the differences have increased over time. Some IE languages have moved from synthetic verb systems to largely periphrastic systems. The pronouns of periphrastic forms are in brackets when they appear. Some of these verbs have undergone a change in meaning as well.

- In Modern Irish beir usually only carries the meaning to bear in the sense of bearing a child, its common meanings are to catch, grab.

- The Hindi verb bharnā, the continuation of the Sanskrit verb, can have a variety of meanings, but the most common is "to fill". The forms given in the table, although etymologically derived from the present indicative, now have the meaning of subjunctive. The present indicative is conjugated periphrastically, using a participle (etymologically the Sanskrit present participle bharant-) and an auxiliary: maiṃ bhartā hūṃ, tū bhartā hai, vah bhartā hai, ham bharte haiṃ, tum bharte ho, ve bharte haiṃ (masculine forms).

- German is not directly descended from Gothic, but the Gothic forms are a close approximation of what the early West Germanic forms of c. 400 AD would have looked like. The cognate of Germanic beranan (English bear) survives in German only in the compound gebären, meaning "bear (a child)".

- The Latin verb ferre is irregular, and not a good representative of a normal thematic verb. In French, other verbs now mean "to carry" and ferre only survives in compounds such as souffrir "to suffer" (from Latin sub- and ferre) and conferer "to confer" (from Latin "con-" and "ferre).

- In Modern Greek, phero φέρω (modern transliteration fero) "to bear" is still used but only in specific contexts not in everyday language. The form that is (very) common today is pherno φέρνω (modern transliteration ferno) meaning "to bring". Additionally, the perfective form of pherno (used for the subjunctive voice and also for the future tense) is also phero.

- In Modern Russian брать (brat) carries the meaning to take. Бремя (bremia) means burden, as something heavy to bear, and derivative беременность (beremennost) means pregnancy.

Comparison of cognates

Main article: Indo-European vocabularySee also

- Grammatical conjugation

- The Horse, The Wheel and Language (book)

- Indo-European copula

- Indo-European sound laws

- Indo-European studies

- Indo-European vocabulary

- Language family

- List of Indo-European languages

- Proto-Indo-European language

- Proto-Indo-European root

Citations and notes

- ^ It includes 449 languages and dialects, according to the 2005 Ethnologue estimate, about half (219) belonging to the Indo-Aryan subbranch.

- ^ "Ethnologue list of language families". Ethnologue.com. http://www.ethnologue.com/ethno_docs/distribution.asp?by=family. Retrieved 2010-08-07.

- ^ "Ethnologue list of languages by number of speakers". Ethnologue.com. http://www.ethnologue.com/ethno_docs/distribution.asp?by=size. Retrieved 2010-08-07.

- ^ a b c Auroux, Sylvain (2000). History of the Language Sciences. Berlin, New York: Walter de Gruyter. p. 1156. ISBN 3110167352. http://books.google.com/?id=yasNy365EywC&pg=PA1156&vq=stephens+sassetti&dq=3110167352.

- ^ M. V. Lomonosov. In: Complete Edition, Moscow, 1952, vol. 7, pp 652–659: Представимъ долготу времени, которою сіи языки раздѣлились. ... Польской и россійской языкъ коль давно раздѣлились! Подумай же, когда курляндской! Подумай же, когда латинской, греч., нѣм., росс. О глубокая древность! [Imagine the depth of time when these languages separated! ... Polish and Russian separated so long ago! Now think how long ago [this happened to] Kurlandic! Think when [this happened to] Latin, Greek, German, and Russian! Oh, great antiquity!]

- ^ "cited on page 14-15." (PDF). http://www.billposer.org/Papers/iephm.pdf. Retrieved 2010-08-07.

- ^ Roger Blench Archaeology and Language: methods and issues. In: A Companion To Archaeology. J. Bintliff ed. 52-74. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 2004. (He erroneously included Egyptian, Japanese, and Chinese in the Indo-European languages, while omitting Hindi.)

- ^ In London Quarterly Review X/2 1813.; cf. Szemerényi 1999:12, footnote 6

- ^ In German it is indogermanisch 'Indo-Germanic' which indicates the east-west extension. That term was first recorded in use in French original as indo-germanique, in 1810 by Conrad Malte-Brun, a French geographer of Danish descent.

- ^ Koch, John T (2010). Celtic from the West Chapter 9: Paradigm Shift? Interpreting Tartessian as Celtic. Oxbow Books, Oxford, UK. pp. 187–295. ISBN 978-1-84217-410-4.

- ^ Koch, John T (2011). Tartessian 2: The Inscription of Mesas do Castelinho ro and the Verbal Complex. Preliminaries to Historical Phonology. Oxbow Books, Oxford, UK. pp. 1–198. ISBN 978-1-907029-07-3. http://www.oxbowbooks.com/bookinfo.cfm/ID/91450//Location/Oxbow.

- ^ such as Schleicher 1861, Szemerényi 1957, Collinge 1985, and Beekes 1995

- ^ Of the Albanian Language. William Martin Leake, London, 1814.

- ^ "The Thracian language". The Linguist List. http://linguistlist.org/forms/langs/LLDescription.cfm?code=txh. Retrieved 2008-01-27. "An ancient language of Southern Balkans, belonging to the Satem group of Indo-European. This language is the most likely ancestor of modern Albanian (which is also a Satem language), though the evidence is scanty. 1st Millennium BC – 500 AD."

- ^ Nakhleh, Luay; Ringe, Don & Warnow, Tandy (2005). "Perfect Phylogenetic Networks: A New Methodology for Reconstructing the Evolutionary History of Natural Languages". Language: Journal of the Linguistic Society of America 81 (2): 382–420. doi:10.1353/lan.2005.0078. http://www.cs.rice.edu/~nakhleh/Papers/NRWlanguage.pdf

- ^ Mallory J.P., D. Q. Adams (Hrsg.): Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture, Fitzroy Dearborn, London, 1997

- ^ Britannica 15th edition, vol.22, 1981, p.588, 594

- ^ "Frederik Kortlandt-The spread of the Indo-Europeans, 1989" (PDF). http://www.kortlandt.nl/publications/art111e.pdf. Retrieved 2010-08-07.

- ^ Lubotsky - The Old Phrygian Areyastis-inscription, Kadmos 27, 9-26, 1988

- ^ Kortlandt - The Thraco-Armenian consonant shift, Linguistique Balkanique 31, 71-74, 1988

- ^ Renfrew, Colin (1987). Archaeology & Language. The Puzzle of the Indo-European Origins. London: Jonathan Cape. ISBN 0-224-02495-7.

- ^ Encyclopaedia Britannica, vol.22, Helen Hemingway Benton Publisher, Chicago, (15th ed.) 1981, p.593

- ^ George S. Lane, Douglas Q. Adams, Britannica 15th edition 22:667, "The Tocharian problem"

- ^ The supposed autochthony of Hittites, the Indo-Hittite hypothesis and migration of agricultural "Indo-European" societies became intrinsically linked together by C. Renfrew. (Renfrew, C 2001a The Anatolian origins of Proto-Indo-European and the autochthony of the Hittites. In R. Drews ed., Greater Anatolia and the Indo-Hittite language. family: 36-63. Washington, DC: Institute for the Study of Man).

- ^ Britannica 15th edition, 22 p. 586 "Indo-European languages, The parent language, Laryngeal theory" - W.C.; p. 589, 593 "Anatolian languages" - Philo H.J. Houwink ten Cate, H. Craig Melchert and Theo P.J. van den Hout

- ^ Britannica 15th edition, 22 p. 594, "Indo-Hittite hypothesis"

- ^ Holm, Hans J. (2008). "The Distribution of Data in Word Lists and its Impact on the Subgrouping of Languages". In Preisach, Christine; Burkhardt, Hans; Schmidt-Thieme, Lars et al.. Data Analysis, Machine Learning, and Applications. Proc. of the 31st Annual Conference of the German Classification Society (GfKl), University of Freiburg, March 7–9, 2007. Studies in Classification, Data Analysis, and Knowledge Organization. Heidelberg-Berlin: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 9783540782391. http://www.hjholm.de/. "The result is a partly new chain of separation for the main Indo-European branches, which fits well to the grammatical facts, as well as to the geographical distribution of these branches. In particular it clearly demonstrates that the Anatolian languages did not part as first ones and thereby refutes the Indo-Hittite hypothesis."

- ^ "Indo-European Languages: Balto-Slavic Family". Utexas.edu. 2008-11-10. http://www.utexas.edu/cola/centers/lrc/iedocctr/ie-lg/Balto-Slavic.html. Retrieved 2010-08-07.

References

- Anthony, David W. (2007). The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691058873. http://books.google.com/books?id=rOG5VcYxhiEC&dq.

- Auroux, Sylvain (2000). History of the Language Sciences. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 3110167352.

- Fortson, Benjamin W. (2004). Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction. Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell. ISBN 1405103159.

- Houwink ten Cate, H. J.; Melchert, H. Craig & van den Hout, Theo P. J. (1981). "Indo-European languages, The parent language, Laryngeal theory". Encyclopædia Britannica. 22 (15th ed.). Chicago: Helen Hemingway Benton.

- Holm, Hans J. (2008). "The Distribution of Data in Word Lists and its Impact on the Subgrouping of Languages". In Preisach, Christine; Burkhardt, Hans; Schmidt-Thieme, Lars et al.. Data Analysis, Machine Learning, and Applications. Proceedings of the 31st Annual Conference of the German Classification Society (GfKl), University of Freiburg, March 7–9, 2007. Heidelberg-Berlin: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 9783540782391.

- Kortlandt, Frederik (1990). "The Spread of the Indo-Europeans". Journal of Indo-European Studies 18 (1–2): 131–140.

- Lubotsky, A. (1988). "The Old Phrygian Areyastis-inscription". Kadmos 27: 9–26.

- Kortlandt, Frederik (1988). "The Thraco-Armenian consonant shift". Linguistique Balkanique 31: 71–74.

- Lane, George S.; Adams, Douglas Q. (1981). "The Tocharian problem". Encyclopædia Britannica. 22 (15th ed.). Chicago: Helen Hemingway Benton.

- Renfrew, C. (2001). "The Anatolian origins of Proto-Indo-European and the autochthony of the Hittites". In Drews, R.. Greater Anatolia and the Indo-Hittite language family. Washington, DC: Institute for the Study of Man. ISBN 0941694771.

- Szemerényi, Oswald; Jones, David; Jones, Irene (1999). Introduction to Indo-European Linguistics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198238703

Further reading

- Beekes, Robert S. P. (1995). Comparative Indo-European Linguistics. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Chakrabarti, Byomkes (1994). A comparative study of Santali and Bengali. Calcutta: K.P. Bagchi & Co.. ISBN 8170741289.

- Collinge, N. E. (1985). The Laws of Indo-European. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Mallory, J.P. (1989). In Search of the Indo-Europeans. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27616-1.

- Renfrew, Colin (1987). Archaeology & Language. The Puzzle of the Indo-European Origins. London: Jonathan Cape. ISBN 0-224-02495-7.

- Meillet, Antoine. Esquisse d’une grammaire comparée de l’arménien classique, 1903.

- Ramat, Paolo; Ramat, Anna Giacalone (1998). The Indo-European languages. Routledge.

- Schleicher, August, A Compendium of the Comparative Grammar of the Indo-European Languages (1861/62).

- Strazny, Philip (Ed). (2000). Dictionary of Historical and Comparative Linguistics (1 ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-1579582180.

- Szemerényi, Oswald (1957). "The problem of Balto-Slav unity". Kratylos 2: 97–123.

- Watkins, Calvert (2000). The American Heritage Dictionary of Indo-European Roots. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-618-08250-6.

- Remys, Edmund, General distinguishing features of various Indo-European languages and their relationship to Lithuanian. Berlin, New York: Indogermanische Forschungen, Vol. 112, 2007.

- P. Chantraine (1968), Dictionnaire étymologique de la langue grecque, Klincksieck, Paris.

External links

Databases

- Dyen, Isidore; Kruskal, Joseph; Black, Paul (1997). "Comparative Indo-European". wordgumbo. http://www.wordgumbo.com/ie/cmp/. Retrieved 13 December 2009.

- "Indo-European". LLOW Languages of the World. http://languageserver.uni-graz.at/ls/group?id=4. Retrieved 14 December 2009.

- "Indo-European Documentation Center". Linguistics Research Center, University of Texas at Austin. 2009. http://www.utexas.edu/cola/centers/lrc/iedocctr/ie.html. Retrieved 14 December 2009.

- Lewis, M. Paul, ed (2009). "Language Family Trees: Indo-European". Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Online version (Sixteenth ed.). Dallas, Tex.: SIL International. http://www.ethnologue.com/show_family.asp?subid=2-16.

- "The Linguist List Multitree Portal for Indo-European". Eastern Michigan University. 1989–2007. http://multitree.org/codes/ieur. Retrieved 14 December 2009.

- "Thesaurus Indogermanischer Text- und Sprachmaterialien: TITUS" (in German). TITUS, University of Frankfurt. 2003. http://titus.uni-frankfurt.de/indexe.htm. Retrieved 13 December 2009.

Lexica

- "Indo-European Etymological Dictionary (IEED)". Leiden, Netherlands: Department of Comparative Indo-European Linguistics, Leiden University. http://www.indoeuropean.nl. Retrieved 14 December 2009.

- "Indo-European Roots Index". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (Fourth ed.). Internet Archive: Wayback Machine. August 22, 2008 [2000]. http://web.archive.org/web/20080726143746/www.bartleby.com/61/IEroots.html. Retrieved 9 December 2009.

- Köbler, Gerhard (2000). "Indogermanisches Wörterbuch" (in German). Gerhard Köbler. http://www.koeblergerhard.de/idgwbhin.html. Retrieved 14 December 2009.

- Schalin, Johan (2009). "Lexicon of Early Indo-European Loanwords Preserved in Finnish". Johan Schalin. http://www.iki.fi/jschalin/?cat=10. Retrieved 9 December 2009.

Categories:- Indo-European languages

- Language families

- Indo-European

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.