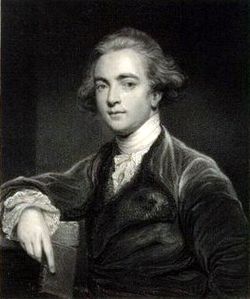

- William Jones (philologist)

-

For other people named William Jones, see William Jones (disambiguation).

Sir William Jones (28 September 1746 – 27 April 1794) was an English philologist and scholar of ancient India, particularly known for his proposition of the existence of a relationship among Indo-European languages. He was also the founder of the Asiatic Society.

Contents

Biography

Jones was born in London at Beaufort Buildings, Westminster; his father (also named William Jones) was a mathematician from Anglesey in Wales, noted for devising the use of the symbol pi. The young William Jones was a linguistic prodigy, learning Greek, Latin, Persian, Arabic, Hebrew and the basics of Chinese writing at an early age.[1] By the end of his life he knew thirteen languages thoroughly and another twenty-eight reasonably well, making him a hyperpolyglot.

Though his father died when he was only three, Jones was still able to go to Harrow in September 1753 and on to Oxford University. He graduated from University College, Oxford in 1768 and became M.A. in 1773. Too poor, even with his award, to pay the fees, he gained a job tutoring the seven-year-old Lord Althorp, son of Earl Spencer. He embarked on a career as a tutor and translator for the next six years. During this time he published Histoire de Nader Chah (1770), a French translation of a work originally written in Persian by Mirza Mehdi Khan Astarabadi. This was done at the request of King Christian VII of Denmark who had visited Jones - who by the age of 24 had already acquired a reputation as an orientalist. This would be the first of numerous works on Persia, Turkey, and the Middle East in general.

In 1770, he joined the Middle Temple and studied law for three years, which would eventually lead him to his life-work in India; after a spell as a circuit judge in Wales, and a fruitless attempt to resolve the issues of the American Revolution in concert with Benjamin Franklin in Paris, he was appointed puisne judge to the Supreme Court of Bengal on 4 March 1783, and on 20 March he was knighted. In April 1783 he married Anna Maria Shipley, the eldest daughter of Dr. Jonathan Shipley, Bishop of Landaff and Bishop of St Asaph. On 25 September 1783 he arrived in Calcutta.

In the Subcontinent he was entranced by Indian culture, an as-yet untouched field in European scholarship, and on 15 January 1784 he founded the Asiatic Society in Calcutta. Over the next ten years he would produce a flood of works on India, launching the modern study of the subcontinent in virtually every social science. He also wrote on the local laws, music, literature, botany, and geography, and made the first English translations of several important works of Indian literature. He died in Calcutta on 27 April 1794 at the age of 47 and is buried in South Park Street Cemetery[2].

Scholarly contributions

Of all his discoveries, Jones is best known today for making and propagating the observation that Sanskrit bore a certain resemblance to classical Greek and Latin. In The Sanscrit Language (1786) he suggested that all three languages had a common root, and that indeed they may all be further related, in turn, to Gothic and the Celtic languages, as well as to Persian.

His third annual discourse before the Asiatic Society on the history and culture of the Hindus (delivered on 2 February 1786 and published in 1788) with the famed "philologer" passage is often cited as the beginning of comparative linguistics and Indo-European studies. This is Jones' most quoted passage, establishing his tremendous find in the history of linguistics: [3]

The Sanscrit language, whatever be its antiquity, is of a wonderful structure; more perfect than the Greek, more copious than the Latin, and more exquisitely refined than either, yet bearing to both of them a stronger affinity, both in the roots of verbs and the forms of grammar, than could possibly have been produced by accident; so strong indeed, that no philologer could examine them all three, without believing them to have sprung from some common source, which, perhaps, no longer exists; there is a similar reason, though not quite so forcible, for supposing that both the Gothic and the Celtic, though blended with a very different idiom, had the same origin with the Sanscrit; and the old Persian might be added to the same family.

This common source came to be known as Proto-Indo-European.

As early as the mid-17th century Dutchman Marcus Zuerius van Boxhorn (1612–1653) and others had been aware that Ancient Persian belonged to the same language group as the European languages. Similarly, American colonist Jonathan Edwards Jr. published in 1787 a work where he demonstrated that the Algonquian languages across northeastern North America were related to each other, and so were the Iroquoian languages. Nevertheless, it was Jones' discovery that caught the imagination of later scholars and became the semi-mythical origin of modern historical and comparative linguistics.

In 1789 he was the first to translate the Abhijñānaśākuntalam, an Indian play (written in a mix of Sanskrit and Prakrit) into a Western language under the title of Sacontalá or The Fatal Ring; An Indian Drama by Cálidás (Kalidasa). He encouraged his colleague Charles Wilkins to make the first translation of the Bhagavad Gita into English.

Jones is also indirectly responsible for some of the sensibility of the poetry of the English Romantic movement (particularly that of Lord Byron and Samuel Taylor Coleridge), as his translations of "eastern" poetical works were a source for that style.

His book on Hitopadesa can be found here

Latin chess poem

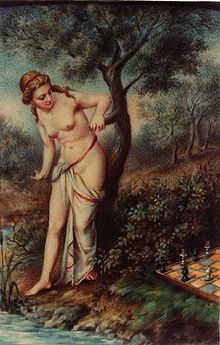

In 1763, at the age of 17, Jones wrote the poem Caissa in Latin hexameters, based on a 658-line poem called "Scacchia, Ludus" published in 1527 by Marco Girolamo Vida, giving a mythical origin of chess that has become well known in the chess world. He also published an English language version of the poem.

In the poem the nymph Caissa initially repels the advances of Mars, the god of war. Spurned, Mars seeks the aid of the god of sport, who creates the game of chess as a gift for Mars to win Caissa's favour. Mars wins her over with the game.

Caissa has been since been characterised as the "goddess" of chess, her name being used in several contexts in modern chess playing.

Schopenhauer's citation

On page two of his main work of 1819, Schopenhauer referred to one of Sir William Jones's publications. Schopenhauer was trying to support the doctrine that "everything that exists for knowledge, and hence the whole of this world, is only object in relation to the subject, perception of the perceiver, in a word, representation."[4] He quoted Sir William Jones's original English:

…how early this basic truth was recognized by the sages of India, since it appears as the fundamental tenet of the Vedânta philosophy ascribed to Vyasa, is proved by Sir William Jones in the last of his essays: "On the Philosophy of the Asiatics" (Asiatic Researches, vol. IV, p. 164): "The fundamental tenet of the Vedânta school consisted not in denying the existence of matter, that is solidity, impenetrability, and extended figure (to deny which would be lunacy), but in correcting the popular notion of it, and in contending that it has no essence independent of mental perception; that existence and perceptibility are convertible terms."

Schopenhauer used Jones's authority to relate the basic principle of his philosophy to what was, according to Jones, the most important underlying proposition of Vedânta. He referred to Sir William Jones's writings in a few other places in his works, but this was the most extensive citation.

References

- ^ Edward Said, Orientalism New York: Random House, page 77.

- ^ The South Park Street Cemetery, Calcutta, published by the Association for the Preservation of Historical Cemeteries in India, 5th ed., 2009

- ^ Jones, Sir William (1824). Discourses delivered before the Asiatic Society: and miscellaneous papers, on the religion, poetry, literature, etc., of the nations of India. Printed for C. S. Arnold. p. 28.

- ^ The World as Will and Representation, § 1

Resources

- Campbell, Lyle. (1997). American Indian languages: The historical linguistics of Native America. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509427-1.

- Cannon, Garland H. (1964). Oriental Jones: A biography of Sir William Jones, 1746-1794. Bombay: Asia Pub. House Indian Council for Cultural Relations.

- Cannon, Garland H. (1979). Sir William Jones: A bibliography of primary and secondary sources. Amsterdam: Benjamins. ISBN 90-272-0998-7.

- Cannon, Garland H.; & Brine, Kevin. (1995). Objects of enquiry: Life, contributions and influence of Sir William Jones. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-1517-6.

- Franklin, Michael J. (1995). Sir William Jones. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. ISBN 0-7083-1295-0.

- Jones, William, Sir. (1970). The letters of Sir William Jones. Cannon, Garland H. (Ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-812404-X.

- Mukherjee, S. N. (1968). Sir William Jones: A study in eighteenth-century British attitudes to India. London, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-05777-9.

- Poser, William J. and Lyle Campbell (1992). Indo-european practice and historical methodology, Proceedings of the Eighteenth Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society, pp. 214–236.

- The 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica, 11th ed. Sir William Jones

External links

- Urs App: William Jones's Ancient Theology. Sino-Platonic Papers Nr. 191 (September 2009) (PDF 3.7 Mb PDF, 125 p.; includes third, sixth, and ninth anniversary discourses)

- The Third Anniversary Discourse, On The Hindus

- Caissa or The Game at Chess; a Poem.

Categories:- English linguists

- Historical linguists

- Indo-Europeanists

- English philologists

- English anthropologists

- Sanskrit scholars

- English Indologists

- English orientalists

- Alumni of University College, Oxford

- People from Westminster

- Translators of Kālidāsa

- 1746 births

- 1794 deaths

- Members of the Middle Temple

- Founders of Indian schools and colleges

- Fellows of the Royal Society

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.