- Human rights in the United States

-

In 1776, Thomas Jefferson proposed a philosophy of human rights inherent to all people in the Declaration of Independence, asserting that "all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness." Historian Joseph J. Ellis calls the Declaration "the most quoted statement of human rights in recorded history".[1]

In 1776, Thomas Jefferson proposed a philosophy of human rights inherent to all people in the Declaration of Independence, asserting that "all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness." Historian Joseph J. Ellis calls the Declaration "the most quoted statement of human rights in recorded history".[1]

Human rights in the United States are legally protected by the Constitution of the United States and amendments,[2][3] conferred by treaty, and enacted legislatively through Congress, state legislatures, and plebiscites (state referenda). Federal courts in the United States have jurisdiction over international human rights laws as a federal question, arising under international law, which is part of the law of the United States.[4][page needed]

The first human rights organization in the Thirteen Colonies of British America, dedicated to the abolition of slavery, was formed by Anthony Benezet in 1775. A year later, the Declaration of Independence would advocate for civil liberties based on the self-evident truth “that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”[5] This view of human liberties postulates that fundamental rights are not granted by the government but are inalienable and inherent to each individual, anteceding government.[6]

Holding to these principles, the United States Constitution, adopted in 1787, created a republic that guaranteed several rights and civil liberties. Those rights and liberties were further codified in the Bill of Rights (the first ten amendments of the Constitution) and subsequently extended over time to more universal applicability through judicial rulings and law and reflecting the evolving norms of society — slavery being constitutionally abolished in 1865 and women's suffrage being established nationally in 1920.

In the 20th century, the United States took a leading role in the creation of the United Nations and in the drafting of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.[7] Much of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was modeled in part on the U.S. Bill of Rights.[8] Even as such, the United States is in violation of the Declaration, in as much that "everyone has the right to leave any country" because the government may prevent the entry and exit of anyone from the United States for foreign policy, national security, or child support rearage reasons by revoking their passport.[9]

In the 21st century, the US actively attempted to undermine the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court.[10]

Contents

Legal framework

Domestic legal protection structure

According to Human Rights: The Essential Reference, "the American Declaration of Independence was the first civic document that met a modern definition of human rights."[11] The Constitution recognizes a number of inalienable human rights, including freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, freedom of religion, the right to keep and bear arms, freedom from cruel and unusual punishment, and the right to a fair trial by jury.[12]

Constitutional amendments have been enacted as the needs of the society evolved. The Ninth Amendment and Fourteenth Amendment recognize that not all human rights have yet been enumerated. The Civil Rights Act and the Americans with Disabilities Act are examples of human rights that were enumerated by Congress well after the Constitution's writing. The scope of the legal protections of human rights afforded by the US government is defined by case law, particularly by the precedent of the Supreme Court of the United States.

Within the federal government, the debate about what may or may not prove to be an emerging human right is held in two forums, the United States Congress which may enumerate these or the Supreme Court which may articulate rights not recognized. Additionally the individual states, either through court action or legislation, have often protected human rights not recognized at federal level (for example Massachusetts being the first, of several, states to recognize same sex marriage.[13]

Effect of international treaties

In the context of human rights and treaties which recognize or create individual rights, there are self-executing and non-self-executing treaties. Non-self-executing treaties, those which ascribe rights which under the Constitution may be assigned by law, require legislative action to execute the contract (treaty) before it can become applicable to law.[14] There are also cases which explicitly require legislative approval according to the Constitution, such as cases which would potentially commit the U.S. to declare war or which require appropriation of funds.

Treaties regarding human rights, which create a duty to refrain from acting in a particular manner or confer specific rights, are generally held to be self-executing, requiring no further legislative action. In cases where legislative bodies refuse to recognize otherwise self-executing treaties by declaring them to be non-self-executing in an act of legislative non-recognition, constitutional scholars argue that such acts violate the separation of powers — in cases of controversy, the judiciary, not Congress, has the authority under Article III to apply treaty law to cases before the court. This is a key provision in cases where the Congress declares a human rights treaty to be non-self-executing, for example, by contending it does not add anything to human rights under U.S. domestic law. The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights is one such case, which, while ratified after more than two decades of inaction, was done so with reservations, understandings, and declarations.[15]

Equality

Racial

See also: Civil Rights Act of 1964 and African-American Civil Rights Movement Lyndon B. Johnson signs the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the first comprehensive legislation prohibiting discrimination on the basis of race and national origin in the workplace in a major industrialized country. Among the guests behind him is Martin Luther King, Jr.

Lyndon B. Johnson signs the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the first comprehensive legislation prohibiting discrimination on the basis of race and national origin in the workplace in a major industrialized country. Among the guests behind him is Martin Luther King, Jr.

The Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution guarantees that "the right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude."[16] In addition, Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits the denial of a citizen of the right to vote based on that citizen's "race, color, or previous condition of servitude".

The United States was the first major industrialized country to enact comprehensive legislation prohibiting discrimination on the basis of race and national origin in the workplace in the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (CRA),[17] while most of the world contains no such recourse for job discrimination.[18] The CRA is perhaps the most prominent civil rights legislation enacted in modern times, has served as a model for subsequent anti-discrimination laws and has greatly expanded civil rights protections in a wide variety of settings.[19] The United States' 1991 provision of recourse for victims of such discrimination for punitive damages and full back pay has virtually no parallel in the legal systems of any other nation.[18]

In addition to individual civil recourse, the United States possesses anti-discrimination government enforcement bodies, such as the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, while only the United Kingdom and Ireland possess faintly analogous bureaucracies.[18] Beginning in 1965, the United States also began a program of affirmative action which not only obliges employers not to discriminate, but also requires them to provide preferences for groups protected under the Civil Rights Act to increase their numbers where they are judged to be underrepresented.[20]

Such affirmative action programs are also applied in college admissions.[20] The United States also prohibits the imposition of any "voting qualification or prerequisite to voting, or standard, practice, or procedure ... to deny or abridge the right of any citizen of the United States to vote on account of race or color", which prevents the use of grandfather clauses, literacy tests, poll taxes and white primaries.

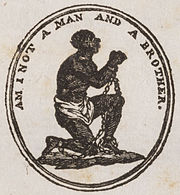

Abolitionist Anthony Benezet and others formed the first human rights nongovernmental organization in the U.S. This image was used as a symbol for their cause.[21][22]

Abolitionist Anthony Benezet and others formed the first human rights nongovernmental organization in the U.S. This image was used as a symbol for their cause.[21][22]

Prior to the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, slavery was legal in some states of the United States until 1865.[23] Influenced by the principles of the Religious Society of Friends, Anthony Benezet formed the Pennsylvania Abolition Society in 1775, believing that all ethnic groups were considered equal and that human slavery was incompatible with Christian beliefs. Benezet extended the recognition of human rights to Native Americans and he argued for a peaceful solution to the violence between the Native and European Americans. Benjamin Franklin became the president of Benezet's abolition society in the late 18th century. In addition, the Fourteenth Amendment was interpreted to permit what was termed Separate but equal treatment of minorities until the United States Supreme Court overturned this interpretation in 1954, which consequently overturned Jim Crow laws.[24][25] Native Americans did not have citizenship rights until the Dawes Act of 1887 and the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924.

Following the 2008 presidential election, Barack Obama was sworn in as the first African-American president of the United States on January 20, 2009.[26] In his Inaugural Address, President Obama stated "A man whose father less than 60 years ago might not have been served at a local restaurant can now stand before you to take a most sacred oath....So let us mark this day with remembrance, of who we are and how far we have traveled".[26]

Gender

See also: Women's suffrage in the United StatesThe Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits the states and the federal government from denying any citizen the right to vote because of that citizen's sex.[27] While this does not necessarily guarantee all women the right to vote, as suffrage qualifications are determined by individual states, it does mean that states' suffrage qualifications may not prevent women from voting due to their gender.[27]

The United States was the first major industrialized country to enact comprehensive CRA legislation prohibiting discrimination on the basis of gender in the workplace[17] while most of the world contains no such recourse for job discrimination.[18] The United States' 1991 provision of recourse for discrimination victims for punitive damages and full back pay has virtually no parallel in the legal systems of any other nation.[18] In addition to individual civil recourse, the United States possesses anti-discrimination government enforcement bodies, such as the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, while only the United Kingdom and Ireland possess faintly analogous bureaucracies.[18] Beginning in 1965, the United States also began a program of affirmative action which not only obliges employers not to discriminate, but also requires them to provide preferences for groups protected under the CRA to increase their numbers where they are judged to be underrepresented.[20] Such affirmative action programs are also applied in college admissions.[20]

The United States was also the first country to legally define sexual harassment in the workplace.[28] Because sexual harassment is therefore a Civil Rights violation, individual legal rights of those harassed in the workplace are comparably stronger in the United States than in most European countries.[28] , Employment Discrimination Law Under Title VII, Oxford University Press US, 2008, ISBN 0-19-533898-7</ref> The Selective Service System does not require women to register for a possible military draft[29] and the United States military does not permit women to serve in some front-line combat units. The U.S does not allow women who work the same jobs as men to be paid the same amount, women only earn 77 cents for every dollar a man earns. [30]

Disability

See also: Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990The United States was the first country in the world to adopt sweeping antidiscrimination legislation for people with disabilities, the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA).[31] The ADA reflected a dramatic shift toward the employment of persons with disabilities to enhance the labor force participation of qualified persons with disabilities and in reducing their dependence on government entitlement programs.[32] The ADA amends the CRA and permits plaintiffs to recover punitive damages.[33] The ADA has been instrumental in the evolution of disability discrimination law in many countries, and has had such an enormous impact on foreign law development that its international impact may be even larger than its domestic impact.[34] Although ADA Title I was found to be unconstitutional, the Supreme Court has extended the protection to people with Acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS).[35]

It is important to note that federal benefits such as Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) and Supplemental Security Income (SSI) are often administratively viewed in the United States as being primarily or near-exclusively the entitlement only of impoverished U.S. people with disabilities, and not applicable to those with disabilities who make significantly above-poverty level income. This is proven in practice by the general fact that in the U.S., if a disabled person on SSI without significant employment income suddenly finds him or her self in a position of employment, with a salary or wage at or above the living wage threshold, s/he will often discover that the benefits to which s/he was previously entitled have been withdrawn by the state-based or federal government, because supposedly the new job "invalidates" the need for this assistance. The U.S. is the only industrialized country in the world to have this particular approach to physical disability assistance programming.

Sexual orientation

The Constitution of the United States explicitly recognizes certain individual rights. The 14th Amendment recognizes that some human rights may exist but are not yet recognized within constitutional law; for example, civil rights for people of color and disability rights were long unrecognized. There may exist additional gender-related civil rights that are presently not recognized by US law but it does not explicitly state any sexual orientation rights. Some states have recognized sexual orientation rights which are discussed below.

The United States Federal Government does not have any substantial body of law relating to marriage; these laws have developed separately within each state. The Full faith and credit clause of the US Constitution ordinarily guarantees the recognition of a marriage performed in one state by another. However, the Congress passed the Defense of Marriage Act of 1996,[36] which affirmed that no state (or other political subdivision within the United States) need recognize a marriage between persons of the same sex, even if the marriage was concluded or recognized in another state and the Federal Government may not recognize same-sex or polygamous marriages for any purpose, even if concluded or recognized by one of the states. The US Constitution denies the federal government any authority to limit state recognition of sexual orientation rights or protections. This federal law only limits the interstate recognition of individual state laws and does not limit state law in any way.

State laws

At an anti-Proposition 8 rally in New York City a protester compares the discrimination blacks experienced with the state of gay rights.

At an anti-Proposition 8 rally in New York City a protester compares the discrimination blacks experienced with the state of gay rights.

Wisconsin was the first state to pass a law explicitly prohibiting discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation.[37] In 1996, Hawaii ruled same-sex marriage is a Hawaiian constitutional right. Massachusetts, Connecticut, Iowa, Vermont, and New Hampshire are the only states that allow same-sex marriage. Same-sex marriage rights were established by the California Supreme Court in 2008, and over 18,000 same-sex couples were married. In November 2008 voters passed Proposition 8, amending the state constitution to deny same-sex couples marriage rights which was upheld in a May 2009 decision which also allowed existing same-sex marriages to stand.[38][39]

Privacy

Privacy is not explicitly stated in the United States Constitution. In the Griswold v. Connecticut case, the Supreme Court ruled that it is implied in the Constitution. In the Roe v. Wade case, the Supreme Court used privacy rights to overturn most laws against abortion in the United States. In the Cruzan v. Director, Missouri Department of Health case, the Supreme Court held that the patient had a right of privacy to terminate medical treatment. In Gonzales v. Oregon, the Supreme Court held that the Federal Controlled Substances Act can not prohibit physician-assisted suicide allowed by the Oregon Death with Dignity Act. The Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of criminalizing oral and anal sex in the Bowers v. Hardwick 478 U.S. 186 (1986) decision; however, it overturned the decision in the Lawrence v. Texas 539 U.S. 558 (2003) case and established the protection to sexual privacy.

Accused

The United States maintains a presumption of innocence in legal procedures. The Fourth, Fifth, Sixth Amendment to the United States Constitution and Eighth Amendment to the United States Constitution deals with the rights of criminal suspects. Later the protection was extended to civil cases as well[40] In the Gideon v. Wainwright case, the Supreme Court requires that indigent criminal defendants who are unable to afford their own attorney be provided counsel at trial. Since the Miranda v. Arizona case, the United States requires police departments to inform arrested persons of their rights, which is later called Miranda warning and typically begins with "You have the right to remain silent."

Freedoms

Freedom of religion

Main article: Freedom of religion in the United StatesThe establishment clause of the first amendment prohibits the establishment of a national religion by Congress or the preference of one religion over another. The clause was used to limit school praying, beginning with Engel v. Vitale, which ruled government-led prayer unconstitutional. Wallace v. Jaffree banned moments of silence allocated for praying. The Supreme Court also ruled clergy-led prayer at public high school graduations unconstitutional with Lee v. Weisman.

The free exercise clause guarantees the free exercise of religion. The Supreme Court's Lemon v. Kurtzman decision established the "Lemon test" exception, which details the requirements for legislation concerning religion. The Employment Division v. Smith decision, the Supreme Court maintained a "neutral law of general applicability" can be used to limit religion exercises. In the City of Boerne v. Flores decision, the Religious Freedom Restoration Act was struck down as exceeding congressional power; however, the decision's effect is limited by the Gonzales v. O Centro Espirita Beneficente Uniao do Vegetal decision, which requires states to express compelling interest in prohibiting illegal drug use in religious practices.

Freedom of expression

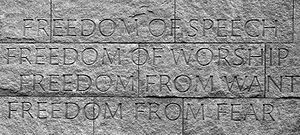

The Four Freedoms are derived from the 1941 State of the Union Address by United States President Franklin Roosevelt delivered to the 77th United States Congress on January 6, 1941. The theme was incorporated into the Atlantic Charter, and it became part of the charter of the United Nations[41] and appears in the preamble of the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights.

The Four Freedoms are derived from the 1941 State of the Union Address by United States President Franklin Roosevelt delivered to the 77th United States Congress on January 6, 1941. The theme was incorporated into the Atlantic Charter, and it became part of the charter of the United Nations[41] and appears in the preamble of the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights. Main articles: Freedom of speech in the United States and Censorship in the United States

Main articles: Freedom of speech in the United States and Censorship in the United StatesThe United States, like other liberal democracies, is supposed to be a constitutional republic based on founding documents that restrict the power of government to preserve the liberty of the people. The freedom of expression (including speech, media, and public assembly) is an important right and is given special protection, as declared by the First amendment of the constitution. According to Supreme Court precedent, the federal and lower governments may not apply prior restraint to expression, with certain exceptions, such as national security and obscenity.[42] There is no law punishing insults against the government, ethnic groups, or religious groups. Symbols of the government or its officials may be destroyed in protest, including the American flag. Legal limits on expression include:

- Solicitation, fraud, specific threats of violence, or disclosure of classified information.

- Advocating the overthrow of the U.S. government through speech or publication, or organizing political parties which advocate the overthrow of the U.S. government (the Smith Act).[43]

- Civil offenses involving defamation, fraud, or workplace harassment

- Copyright violations

- Federal Communications Commission rules governing the use of broadcast media.

- Crimes involving sexual obscenity in pornography and text only erotic stories.

- Ordinances requiring mass demonstrations on public property to register in advance.

- The use of free speech zones and protest free zones.

- Military censorship of blogs written by military personnel claiming some include sensitive information ineligible for release. Some critics view military officials as trying to suppress dissent from troops in the field.[44][45] The US Constitution specifically limits the human rights of active duty members, and this constitutional authority is used to limit speech rights by members in this and in other ways.

Some laws remain controversial due to concerns that they infringe on freedom of expression. These include the Digital Millennium Copyright Act[46] and the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act.[47]

Although Americans are supposed to enjoy the freedom to peacefully protest, protesters are sometimes mistreated, arrested or jailed. On February 19, 2011, Ray McGovern was dragged out of a speech by Hillary Clinton on Internet freedom, in which she said that people should be free to protest without fear of violence. McGovern, who was wearing a Veterans for Peace t-shirt, stood up during the speech and silently turned his back on Clinton. He was then assaulted by undercover and uniformed police, roughed up, handcuffed and jailed. He suffered bruises and lacerations in the attack which required medical treatment.[48] Protesters have also been arrested for protesting outside of designated “free speech zones”.[49] At the 2004 Republican National Convention in New York City, over 1,700 protesters were arrested.[50] On May 4, 1970, Ohio National Guardsmen opened fire on protesting students at Kent State University, killing four students. Investigators determined that 28 Guardsmen fired 61 to 67 shots. The Justice Department concluded that the Guardsmen were not in danger and that their claim that they fired in self-defense was untrue. The nearest student was almost 100 yards away at the time of the shooting.[51] On March 7, 1965, approximately 600 civil rights marchers were violently dispersed by state and local police near the Edmund Pettus Bridge outside of Selma, Alabama.[52]

In two high profile cases, grand juries have decided that Time magazine reporter Matthew Cooper and New York Times reporter Judith Miller must reveal their sources in cases involving CIA leaks. Time magazine exhausted its legal appeals, and Mr. Cooper eventually agreed to testify. Miller was jailed for 85 days before cooperating. U.S. District Chief Judge Thomas F. Hogan ruled that the First Amendment does not insulate Time magazine reporters from a requirement to testify before a criminal grand jury that's conducting the investigation into the possible illegal disclosure of classified information.

Approximately 30,000 government employees and contractors are currently employed to monitor telephone calls and other communications.[53]

Freedom of movement

Further information: Freedom of movement under United States lawAs per § 707(b) of the Foreign Relations Authorization Act, Fiscal Year 1979,[54] United States passports are required to enter and exit the country, and as per the Passport Act of 1926 and Haig v. Agee, the Presidential administration may deny or revoke passports for foreign policy or national security reasons at any time. Perhaps the most notable example of enforcement of this ability was the 1948 denial of a passport to U.S. Representative Leo Isacson, who sought to go to Paris to attend a conference as an observer for the American Council for a Democratic Greece, a Communist front organization, because of the group's role in opposing the Greek government in the Greek Civil War.[55][56]

The United States prevents U.S. citizens to travel to Cuba, citing national security reasons, as part of an embargo against Cuba that has been condemned as an illegal act by the United Nations General Assembly.[57] The current exception to the ban on travel to the island, permitted since April 2009, has been an easing of travel restrictions for Cuban-Americans visiting their relatives. Restrictions continue to remain in place for the rest of the American populace.[58]

On June 30, 2010, the American Civil Liberties Union filed a lawsuit on behalf of ten people who are either U.S. citizens or legal residents of the U.S., challenging the constitutionality of the government's "no-fly" list. The plaintiffs have not been told why they are on the list. Five of the plaintiffs have been stranded abroad. It is estimated that the "no-fly" list contained about 8,000 names at the time of the lawsuit.[59]

The Secretary of State can deny a passport to anyone imprisoned, on parole, or on supervised release for a conviction for international drug trafficking or sex tourism, or to anyone who is behind on their child support payments.[60]

The following case precedents are typically cited in defense of unencumbered travel within the United States:

"The use of the highway for the purpose of travel and transportation is not a mere privilege, but a common fundamental right of which the public and individuals cannot rightfully be deprived." Chicago Motor Coach v. Chicago, 169 NE 221.

"The right of the citizen to travel upon the public highways and to transport his property thereon, either by carriage or by automobile, is not a mere privilege which a city may prohibit or permit at will, but a common law right which he has under the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness." Thompson v. Smith, 154 SE 579.

"Undoubtedly the right of locomotion, the right to move from one place to another according to inclination, is an attribute of personal liberty, and the right, ordinarily, of free transit from or through the territory of any State is a right secured by the 14th amendment and by other provisions of the Constitution." Schactman v. Dulles, 96 App DC 287, 293.

"The right to travel is a well-established common right that does not owe its existence to the federal government. It is recognized by the courts as a natural right." Schactman v. Dulles 96 App DC 287, 225 F2d 938, at 941.

"The right to travel is a part of the liberty of which the citizen cannot be deprived without due process of law under the Fifth Amendment." Kent v. Dulles, 357 US 116, 125.

Freedom of association

Further information: Freedom of associationFreedom of association is the right of individuals to come together in groups for political action or to pursue common interests.

Freedom of association in the U.S. is restricted by the Smith Act, which bans political parties which advocate the violent overthrow of the U.S. government.[43]

Between 1956 and 1971, the FBI attempted to "expose, disrupt, misdirect, discredit, or otherwise neutralize" radical groups through the COINTELPRO program.[61]

In 2008, the Maryland State Police admitted that they had added the names of Iraq War protesters and death penalty opponents to a terrorist database. They also admitted that other "protest groups" were added to the terrorist database, but did not specify which groups. It was also discovered that undercover troopers used aliases to infiltrate organizational meetings, rallies and group e-mail lists. Police admitted there was "no evidence whatsoever of any involvement in violent crime" by those classified as terrorists.[62]

National security exceptions

Further information: National Security Strategy of the United StatesThe United States government has declared martial law,[63] suspended (or claimed exceptions to) some rights on national security grounds, typically in wartime and conflicts such as the United States Civil War,[63][64] Cold War or the War against Terror.[64] 70,000 Americans of Japanese ancestry were legally interned during World War II under Executive Order 9066. In some instances the federal courts have allowed these exceptions, while in others the courts have decided that the national security interest was insufficient. Presidents Lincoln, Wilson, and F.D. Roosevelt ignored such judicial decisions.[64]

Historical restrictions

Sedition laws have sometimes placed restrictions on freedom of expression. The Alien and Sedition Acts, passed by President John Adams during an undeclared naval conflict with France, allowed the government to punish "false" statements about the government and to deport "dangerous" immigrants. The Federalist Party used these acts to harass supporters of the Democratic-Republican Party. While Woodrow Wilson was president, another broad sedition law called the Sedition Act of 1918, was passed during World War I. It also caused the arrest and ten year sentencing of Socialist Party of America Presidential candidate Eugene V. Debs for speaking out against the atrocities of World War I, although he would later be released early by President Warren G. Harding. Countless others, labeled as "subverts" (especially the Wobblies), were investigated by the Woodrow Wilson Administration.

Presidents have claimed the power to imprison summarily, under military jurisdiction, those suspected of being combatants for states or groups at war against the United States. Abraham Lincoln invoked this power in the American Civil War to imprison Maryland secessionists. In that case, the Supreme Court concluded that only Congress could suspend the writ of habeas corpus, and the government released the detainees. During World War II, the United States interned thousands of Japanese-Americans on alleged fears that Japan might use them as saboteurs.

The Fourth Amendment of the United States Constitution forbids unreasonable search and seizure without a warrant, but some administrations have claimed exceptions to this rule to investigate alleged conspiracies against the government. During the Cold War, the Federal Bureau of Investigation established COINTELPRO to infiltrate and disrupt left-wing organizations, including those that supported the rights of black Americans.

National security, as well as other concerns like unemployment, has sometimes led the United States to toughen its generally liberal immigration policy. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 all but banned Chinese immigrants, who were accused of crowding out American workers.

Nationwide Suspicious Activity Reporting Initiative

The federal government has set up a data collection and storage network that keeps a wide variety of data on tens of thousands of Americans who have not been accused of committing a crime. Operated primarily under the direction of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the program is known as the Nationwide Suspicious Activity Reporting Initiative or SAR. Reports of suspicious behavior noticed by local law enforcement or by private citizens are forwarded to the program, and profiles are constructed of the persons under suspicion.[65] see also Fusion Center.

Labor rights

Main article: Labor rightsLabor rights in the United States have been linked to basic constitutional rights.[66] Comporting with the notion of creating an economy based upon highly skilled and high wage labor employed in a capital-intensive dynamic growth economy, the United States enacted laws mandating the right to a safe workplace, Workers compensation, Unemployment insurance, fair labor standards, collective bargaining rights, Social Security, along with laws prohibiting child labor and guaranteeing a minimum wage.[67] While U.S. workers tend to work longer hours than other industrialized nations, lower taxes and more benefits give them a larger disposable income than those of most industrialized nations, however the advantage of lower taxes have been challenged. See: Disposable and discretionary income. U.S. workers are among the most productive in the world.[68] During the 19th and 20th centuries, safer conditions and workers' rights were gradually mandated by law.[69] In 1935, the National Labor Relations Act recognized and protected "the rights of most workers in the private sector to organize labor unions, to engage in collective bargaining, and to take part in strikes and other forms of concerted activity in support of their demands." However, many states hold to the principle of at-will employment, which says an employee can be fired for any or no reason, without warning and without recourse, unless violation of State or Federal civil rights laws can be proven.

Health care

See also: Health care in the United StatesThe Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted by the United Nations in 1948, states that “everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of oneself and one’s family, including food, clothing, housing, and medical care.”[70] In addition, the Principles of Medical Ethics of the American Medical Association require medical doctors to respect the human rights of the patient, including that of providing medical treatment when it is needed.[71] Americans' rights in health care are regulated by the US Patients' Bill of Rights.[citation needed]

Unlike most other industrialized nations, the United States does not offer most of its citizens subsidized health care. The United States Medicaid program provides subsidized coverage to some categories of individuals and families with low incomes and resources, including children, pregnant women, and very low-income people with disabilities (higher-earning people with disabilities do not qualify for Medicaid, although they do qualify for Medicare). However, according to Medicaid's own documents, "the Medicaid program does not provide health care services, even for very poor persons, unless they are in one of the designated eligibility groups."[72]

Nonetheless, some states offer subsidized health insurance to broader populations. Coverage is subsidized for persons age 65 and over, or who meet other special criteria through Medicare. Every person with a permanent disability, both young and old, is inherently entitled to Medicare health benefits — a fact not all disabled US citizens are aware of. However, just like every other Medicare recipient, a disabled person finds that his or her Medicare benefits only cover up to 80% of anything in the U.S. medical system, and that the other 20% must be paid by other means (typically supplemental, privately-held insurance plans, or cash out of the person's own pocket). Therefore, even the Medicare program is not truly national health insurance or universal health care the way most of the rest of the industrialized world understands it.

The Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act of 1986, an unfunded mandate, mandates that no person may ever be denied emergency services regardless of ability to pay, citizenship, or immigration status.[73] The Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act has been criticized by the American College of Emergency Physicians as an unfunded mandate.[74][75]

46.6 million residents, or 15.9 percent, were without health insurance coverage in 2005.[76] This number includes about ten million non-citizens, millions more who would be eligible for Medicaid but have never applied, and 18 million with annual household incomes above $50,000.[77] According to a study led by the Johns Hopkins Children's Center, uninsured children who are hospitalized are 60% more likely to die than children who are covered by health insurance.[78]

Justice system

The Fourth, Fifth, Sixth and Eighteenth Amendments of the Bill of Rights, along with the Fourteenth Amendment, ensure that criminal defendants have significant procedural rights that are unsurpassed by any other justice system.[79] The Fourteenth Amendment's incorporation of due process rights adds these constitutional protections to the state and local levels of law enforcement.[79] Similarly, the United States possesses a system of judicial review over government action more powerful than any other in the world.[80]

Death penalty

Further information: Capital punishment in the United States and Capital punishment debateCapital punishment is controversial. Death penalty opponents regard the death penalty as inhumane[81] and criticize it for its irreversibility[82] and assert that it lacks a deterrent effect,[83] as have several studies[84][85] and debunking studies which claim to show a deterrent effect.[86] According to Amnesty International, "the death penalty is the ultimate, irreversible denial of human rights."[82]

The 1972 US Supreme Court case Furman v. Georgia 408 U.S. 238 (1972) held that arbitrary imposition of the death penalty at the states' discretion constituted cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth Amendment to the United States Constitution. In California v. Anderson 64 Cal.2d 633, 414 P.2d 366 (Cal. 1972), the Supreme Court of California classified capital punishment as cruel and unusual and outlawed the use of capital punishment in California, until it was reinstated in 1976 after the federal supreme court rulings Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S. 153 (1976), Jurek v. Texas, 428 U.S. 262 (1976), and Proffitt v. Florida, 428 U.S. 242 (1976).[87] As of January 25, 2008, the death penalty has been abolished in the District of Columbia and fourteen states, mainly in the Northeast and Midwest.[88]

The UN special rapporteur recommended to a committee of the UN General Assembly that the United States be found to be in violation of Article 6 the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights in regards to the death penalty in 1998, and called for an immediate capital punishment moratorium.[89] The recommendation of the special rapporteur is not legally binding under international law, and in this case the UN did not act upon the lawyer's recommendation.

Since the reinstatement of the death penalty in 1976 there have been 1077 executions in the United States (as of May 23, 2007).[90] There were 53 executions in 2006.[91] Texas overwhelmingly leads the United States in executions, with 379 executions from 1976 to 2006;[92] the second-highest ranking state is Virginia, with 98 executions.[93]

A ruling on March 1, 2005 by the Supreme Court in Roper v. Simmons prohibits the execution of people who committed their crimes when they were under the age of 18.[94] Between 1990 and 2005, Amnesty International recorded 19 executions in the United States for crime committed by a juvenile.[95]

It is the official policy of the European Union and a number of non-EU nations to achieve global abolition of the death penalty. For this reason the EU is vocal in its criticism of the death penalty in the US and has submitted amicus curiae briefs in a number of important US court cases related to capital punishment.[96] The American Bar Association also sponsors a project aimed at abolishing the death penalty in the United States,[97] stating as among the reasons for their opposition that the US continues to execute minors and the mentally retarded, and fails to protect adequately the rights of the innocent.[98]

Some opponents criticize the over-representation of blacks on death row as evidence of the unequal racial application of the death penalty. This over-representation is not limited to capital offenses, in 1992 although blacks account for 12% of the US population, about 34 percent of prison inmates were from this group.[99] In McCleskey v. Kemp, it was alleged the capital sentencing process was administered in a racially discriminatory manner in violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

In 2003, Amnesty International reported those who kill whites are more likely to be executed than those who kill blacks, citing of the 845 people executed since 1977, 80 percent were put to death for killing whites and 13 percent were executed for killing blacks, even though blacks and whites are murdered in almost equal numbers.[100]

Prison system

See also: Incarceration in the United States and Cutter v. WilkinsonThe United States is seen by social critics,[101] including international and domestic human rights groups and civil rights organizations, as a state that violates fundamental human rights, because of disproportionately heavy, in comparison with other countries, reliance on crime control, individual behavior control (civil liberties), and societal control of disadvantaged groups through a harsh police and criminal justice system. The U.S. penal system is implemented on the federal, and in particular on the state and local levels. This social policy has resulted in a high rate of incarceration, which affects Americans from the lowest socioeconomic backgrounds and racial minorities the hardest.[102][103]

Some have criticized the United States for having an extremely large prison population, where there have been reported abuses.[104] As of 2004 the United States had the highest percentage of people in prison of any nation. There were more than 2.2 million in prisons or jails, or 737 per 100,000 population, or roughly 1 out of every 136 Americans. According to The National Council on Crime and Delinquency, since 1990 the incarceration of youth in adult jails has increased 208%.[105] In some states youth - juvenile is defined as young as 13 years old. The researchers for this report found that Juveniles often were incarcerated to await trial for up to two years and subjected to the same treatment of mainstream inmates. The incarcerated adolescent is often subjected to a highly traumatic environment during this developmental stage. The long term effects are often irreversible and detrimental.[106] "Human Rights Watch believes the extraordinary rate of incarceration in the United States wreaks havoc on individuals, families and communities, and saps the strength of the nation as a whole."[107]

Examples of mistreatment claimed include prisoners left naked and exposed in harsh weather or cold air;[108] "routine" use of rubber bullets[109] and pepper spray;,[108][109][109] solitary confinement of violent prisoners in soundproofed cells for 23 or 24 hours a day;[108][110] and a range of injuries from serious injury to fatal gunshot wounds, with force at one California prison "often vastly disproportionate to the actual need or risk that prison staff faced."[109] Such behaviors are illegal, and "professional standards clearly limit staff use of force to that which is necessary to control prisoner disorder."[109]

Human Rights Watch raised concerns with prisoner rape and medical care for inmates.[111] In a survey of 1,788 male inmates in Midwestern prisons by Prison Journal, about 21% claimed they had been coerced or pressured into sexual activity during their incarceration and 7% claimed that they had been raped in their current facility.[112] Tolerance of serious sexual abuse and rape in United States prisons are consistently reported as widespread.[citation needed] It has been fought against by organizations such as Stop Prisoner Rape.

The United States has been criticized for having a high amount of non-violent and victim-less offenders incarcerated,[107][113][114] as half of all persons incarcerated under State jurisdiction are for non-violent offences and 20 percent are incarcerated for drug offences, mostly for possession of cannabis.[115][116]

The United States is the only country in the world allowing sentencing of young adolescents to life imprisonment without the possibility of parole. There are currently 73 Americans serving such sentences for crimes they committed at the age of 13 or 14. In December 2006 the United Nations took up a resolution calling for the abolition of this kind of punishment for children and young teenagers. 185 countries voted for the resolution and only the United States against.[117]

Police brutality

In a 1999 report, Amnesty International said it had "documented patterns of ill-treatment across the U.S., including police beatings, unjustified shootings and the use of dangerous restraint techniques."[118] According to a 1998 Human Rights Watch report, incidents of police use of excessive force had occurred in cities throughout the U.S., and this behavior goes largely unchecked.[119] An article in USA Today reports that in 2006, 96% of cases referred to the U.S. Justice Department for prosecution by investigative agencies were declined. In 2005, 98% were declined.[120] In 2001, the New York Times reported that the U.S. government is unable or unwilling to collect statistics showing the precise number of people killed by the police or the prevalence of the use of excessive force.[121] Since 1999, at least 148 people have died in the United States and Canada after being shocked with Tasers by police officers, according to a 2005 ACLU report.[122] In one case, a handcuffed suspect was tasered nine times by a police officer before dying, and six of those taserings occurred within less than three minutes. The officer was fired and faced the possibility of criminal charges.[123]

War on Terrorism

See also: War on Terrorism and Criticism of the War on TerrorismInhumane treatment and torture of captured non-citizens

See also: Torture and the United States and CIA prison systemInternational and U.S. law prohibits torture and other ill-treatment of any person in custody in all circumstances.[124] However, the United States Government has categorized a large number of people as unlawful combatants, a United States classification used mainly as an excuse to bypass international law, which denies the privileges of prisoner of war (POW) designation of the Geneva Conventions.[125]

Certain practices of the United States military and Central Intelligence Agency have been condemned by some sources domestically and internationally as torture.[126][127] A fierce debate regarding non-standard interrogation techniques[128] exists within the US civilian and military intelligence community, with no general consensus as to what practices under what conditions are acceptable.

Abuse of prisoners is considered a crime in the United States Uniform Code of Military Justice. According to a January 2006 Human Rights First report, there were 45 suspected or confirmed homicides while in US custody in Iraq and Afghanistan; "Certainly 8, as many as 12, people were tortured to death."[129]

Abu Ghraib prison abuse

See also: Abu Ghraib torture and prisoner abuseIn 2004, photos showing humiliation and abuse of prisoners were leaked from Abu Ghraib prison, causing a political and media scandal in the US. Forced humiliation of the detainees included, but is not limited to nudity, rape, human piling of nude detainees, masturbation, eating food out of toilets, crawling on hand and knees while American soldiers were sitting on their back sometimes requiring them to bark like dogs, and hooking up electrical wires to fingers, toes, and penises.[130] Bertrand Ramcharan, acting UN High Commissioner for Human Rights stated that while the removal of Saddam Hussein represented "a major contribution to human rights in Iraq" and that the United States had condemned the conduct at Abu Ghraib and pledged to bring violators to justice, "willful killing, torture and inhuman treatment" represented a grave breach of international law and "might be designated as war crimes by a competent tribunal."[131]

In addition to the acts of humiliation, there were more violent claims, such as American soldiers sodomizing detainees (including an event involving an underage boy), an incident where a phosphoric light was broken and the chemicals poured on a detainee, repeated beatings, and threats of death.[130] Six military personnel were charged with prisoner abuse in the Abu Ghraib torture and prisoner abuse scandal. The harshest sentence was handed out to Charles Graner, who received a 10 year sentence to be served in a military prison and a demotion to private; the other offenders received lesser sentences.[132]

In their report The Road to Abu Ghraib, Human Rights Watch describe how:

The severest abuses at Abu Ghraib occurred in the immediate aftermath of a decision by Secretary Rumsfeld to step up the hunt for "actionable intelligence" among Iraqi prisoners. The officer who oversaw intelligence gathering at Guantanamo was brought in to overhaul interrogation practices in Iraq, and teams of interrogators from Guantanamo were sent to Abu Ghraib. The commanding general in Iraq issued orders to "manipulate an internee's emotions and weaknesses." Military police were ordered by military intelligence to "set physical and mental conditions for favorable interrogation of witnesses." The captain who oversaw interrogations at the Afghan detention center where two prisoners died in detention posted "Interrogation Rules of Engagement" at Abu Ghraib, authorizing coercive methods (with prior written approval of the military commander) such as the use of military guard dogs to instill fear that violate the Geneva Conventions and the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman Degrading Treatment or Punishment.[133]

Enhanced interrogation and waterboarding

See also: Waterboarding and Enhanced interrogation techniquesOn February 6, 2008, the CIA director General Michael Hayden stated that the CIA had used waterboarding on three prisoners during 2002 and 2003, namely Khalid Shaikh Mohammed, Abu Zubayda and Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri.[134][135]

The June 21, 2004 issue of Newsweek stated that the Bybee memo, a 2002 legal memorandum drafted by former OLC lawyer John Yoo that described what sort of interrogation tactics against suspected terrorists or terrorist affiliates the Bush administration would consider legal, was "prompted by CIA questions about what to do with a top Qaeda captive, Abu Zubaydah, who had turned uncooperative ... and was drafted after White House meetings convened by George W. Bush's chief counsel, Alberto Gonzales, along with Defense Department general counsel William Haynes and David Addington, Vice President Dick Cheney's counsel, who discussed specific interrogation techniques", citing "a source familiar with the discussions". Amongst the methods they found acceptable was waterboarding.[136]

In November 2005, ABC News reported that former CIA agents claimed that the CIA engaged in a modern form of waterboarding, along with five other "enhanced interrogation techniques," against suspected members of al Qaeda.

UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Louise Arbour, stated on the subject of waterboarding "I would have no problems with describing this practice as falling under the prohibition of torture", and that violators of the UN Convention Against Torture should be prosecuted under the principle of universal jurisdiction.[137]

Bent Sørensen, Senior Medical Consultant to the International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims and former member of the United Nations Committee Against Torture has said:

It’s a clear-cut case: Waterboarding can without any reservation be labeled as torture. It fulfils all of the four central criteria that according to the United Nations Convention Against Torture (UNCAT) defines an act of torture. First, when water is forced into your lungs in this fashion, in addition to the pain you are likely to experience an immediate and extreme fear of death. You may even suffer a heart attack from the stress or damage to the lungs and brain from inhalation of water and oxygen deprivation. In other words there is no doubt that waterboarding causes severe physical and/or mental suffering – one central element in the UNCAT’s definition of torture. In addition the CIA’s waterboarding clearly fulfills the three additional definition criteria stated in the Convention for a deed to be labeled torture, since it is 1) done intentionally, 2) for a specific purpose and 3) by a representative of a state – in this case the US.[138]

Lt. Gen. Michael D. Maples, the director of the Defense Intelligence Agency, concurred by stating, in a hearing before the Senate Armed Services Committee, that he believes waterboarding violates Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions.[139]

The CIA director testified that waterboarding has not been used since 2003.[140]

In April 2009, the Obama administration released four memos in which government lawyers from the Bush administration approved tough interrogation methods used against 28 terror suspects. The rough tactics range from waterboarding (simulated drowning) to keeping suspects naked and denying them solid food.[141]

These memos were accompanied by the Justice Department's release of four Bush-era legal opinions covering (in graphic and extensive detail) the interrogation of 14 high-value terror detainees using harsh techniques beyond waterboarding. These additional techniques include keeping detainees in a painful standing position for long periods (Used often, once for 180 hours),[142] using a plastic neck collar to slam detainees into walls, keeping the detainee's cell cold for long periods, beating and kicking the detainee, insects placed in a confinement box (the suspect had a fear of insects), sleep-deprivation, prolonged shackling, and threats to a detainee's family. One of the memos also authorized a method for combining multiple techniques.[141][143]

Details from the memos also included the number of times that techniques such as waterboarding were used. A footnote said that one detainee was waterboarded 83 times in one month, while another was waterboarded 183 times in a month.[144] [145] This may have gone beyond even what was allowed by the CIA's own directives, which limit waterboarding to 12 times a day.[145] The Fox News website carried reports from an un-named US official who claimed that these were the number of pourings, not the number of sessions.[146]

Physicians for Human Rights has accused the Bush administration of conducting illegal human experiments and unethical medical research during interrogations of suspected terrorists.[147] The group has suggested this activity was a violation of the standards set by the Nuremberg Trials.[148]

Guantánamo Bay

The United States maintains a detention center at its military base at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba where numerous enemy combatants of the war on terror are held. The detention center has been the source of various controversies regarding the legality of the center and the treatment of detainees.[149][150] Amnesty International has called the situation "a human rights scandal" in a series of reports.[151] 775 detainees have been brought to Guantánamo. Of these, many have been released without charge. As of May 2011, 171 detainees remain at Guantanamo.[152] The United States assumed territorial control over Guantánamo Bay under the 1903 Cuban-American Treaty, which granted the United States a perpetual lease of the area.[153] United States, by virtue of its complete jurisdiction and control, maintains "de facto" sovereignty over this territory, while Cuba retained ultimate sovereignty over the territory. The current government of Cuba regards the U.S. presence in Guantánamo as illegal and insists the Cuban-American Treaty was obtained by threat of force in violation of international law.[154]

A delegation of UN Special Rapporteurs to Guantanamo Bay claimed that interrogation techniques used in the detention center amount to degrading treatment in violation of the ICCPR and the Convention Against Torture.[155]

In 2005 Amnesty International expressed alarm at the erosion in civil liberties since the 9/11 attacks. According to Amnesty International:

- The Guantánamo Bay detention camp has become a symbol of the United States administration’s refusal to put human rights and the rule of law at the heart of its response to the atrocities of 11 September 2001. It has become synonymous with the United States executive’s pursuit of unfettered power, and has become firmly associated with the systematic denial of human dignity and resort to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment that has marked the USA’s detentions and interrogations in the "war on terror".[156]

Amnesty International also condemned the Guantánamo facility as "the gulag of our times", which raised heated conversation in the United States. The purported legal status of "unlawful combatants" in those nations currently holding detainees under that name has been the subject of criticism by other nations and international human rights institutions including Human Rights Watch and the International Committee of the Red Cross. The ICRC, in response to the US-led military campaign in Afghanistan, published a paper on the subject.[157] HRW cites two sergeants and a captain accusing U.S. troops of torturing prisoners in Iraq and Afghanistan.[158]

However, former Republican governor Mike Huckabee, for example, has stated that the conditions in Guantánamo are better than most US prisons.[159]

The US government argues that even if detainees were entitled to POW status, they would not have the right to lawyers, access to the courts to challenge their detention, or the opportunity to be released prior to the end of hostilities and that nothing in the Third Geneva Convention provides POWs such rights, and POWs in past wars have generally not been given these rights.[160] The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld on June 29, 2006 that they were entitled to the minimal protections listed under Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions.[161] Following this, on July 7, 2006, the Department of Defense issued an internal memo stating that prisoners would in the future be entitled to protection under Common Article 3.[162][163][164]

Extraordinary rendition

United States citizens and foreign nationals are occasionally captured and abducted outside of the United States and transferred to secret US administered detention facilities, sometimes being held incommunicado for periods of months or years, a process known as extraordinary rendition.

According to The New Yorker, "The most common destinations for rendered suspects are Egypt, Morocco, Syria, and Jordan, all of which have been cited for human-rights violations by the State Department, and are known to torture suspects."[165]

Notable cases

In November 2001, Yaser Esam Hamdi, a U.S. citizen, was captured by Afghan Northern Alliance forces in Konduz, Afghanistan, amongst hundreds of surrendering Taliban fighters and was transferred into U.S. custody. The U.S. government alleged that Hamdi was there fighting for the Taliban, while Hamdi, through his father, has claimed that he was merely there as a relief worker and was mistakenly captured. Hamdi was transferred into CIA custody and transferred to the Guantanamo Bay Naval Base, but when it was discovered that he was a U.S. citizen, he was transferred to naval brig in Norfolk, Virginia and then he was transferred brig in Charleston, South Carolina. The Bush Administration identified him as an unlawful combatant and denied him access to an attorney or the court system, despite his Fifth Amendment right to due process. In 2002 Hamdi's father filed a habeas corpus petition, the Judge ruled in Hamdi's favor and required he be allowed a public defender; however, on appeal the decision was reversed. In 2004, in the case of Hamdi v. Rumsfeld the U.S. Supreme court reversed the dismissal of a habeas corpus petition and ruled detainees who are U.S. citizens must have the ability to challenge their detention before an impartial judge.

In December 2004, Khalid El-Masri, a German citizen, was apprehended by Macedonian authorities when traveling to Skopje because his name was similar to Khalid al-Masri, an alleged mentor to the al-Qaeda Hamburg cell. After being held in a motel in Macedonia for over three weeks he was transferred to the CIA and extradited to Afghanistan. While held in Afghanistan, El-Masri claims he was sodomized, beaten, and repeatedly interrorgated about alleged terrorist ties.[166] After being in custody for five months, Condoleezza Rice learned of his detention and ordered his release. El-Masri was released at night on a desolate road in Albania, without apology, or funds to return home. He was intercepted by Albanian guards, who believed him to be a terrorist due to his haggard and unkept appearance. He was subsequently reunited with his wife who had returned to her family in Lebanon, with their children, because she thought her husband had abandoned them. Using isotope analysis, scientists at the Bavarian archive for geology in Munich analyzed his hair and verified that he was malnourished during his disappearance.[167]

In 2007, U.S. President Bush signed an Executive order banning the use of torture in the CIA's interrogation program.[168]

Extrajudicial killings

On 30 April 2011, United States forces, authorised by the President of the United States, carried out the extrajudicial killing of Al-qaeda leader Osama Bin Laden on Pakistani territory.[169]

International comparison

According to Canadian historian Michael Ignatieff, during and after the Cold War, the United States placed greater emphasis than other nations on human rights as part of its foreign policy, awarded foreign aid to facilitate human rights progress, and annually assessed the human rights records of other national governments.[7]

Support

The U.S. Department of State publishes a yearly report "Supporting Human Rights and Democracy: The U.S. Record" in compliance with a 2002 law which requires the Department to report on actions taken by the U.S. Government to encourage respect for human rights.[170] It also publishes a yearly "Country Reports on Human Rights Practices.".[171] In 2006 the United States created a "Human Rights Defenders Fund" and "Freedom Awards."[172] The "Ambassadorial Roundtable Series", created in 2006, are informal discussions between newly-confirmed U.S. Ambassadors and human rights and democracy non-governmental organizations.[173] The United States also support democracy and human rights through several other tools.[174]

The "Human Rights and Democracy Achievement Award" recognizes the exceptional achievement of officers of foreign affairs agencies posted abroad.

- In 2006 the award went to Joshua Morris of the embassy in Mauritania who recognized necessary democracy and human rights improvements in Mauritania and made democracy promotion one of his primary responsibilities. He persuaded the Government of Mauritania to re-open voter registration lists to an additional 85,000 citizens, which includes a significant number of Afro-Mauritanian minority individuals. He also organized and managed the largest youth-focused democracy project in Mauritania in 5 years.

- Nathaniel Jensen of the embassy in Vietnam was runner-up. He successfully advanced the human rights agenda on several fronts, including organizing the resumption of a bilateral Human Rights Dialogue, pushing for the release of Vietnam’s prisoners of concern, and dedicating himself to improving religion freedom in northern Vietnam.[175]

Under legislation by congress, the United States declared that countries utilizing child soldiers may no longer be eligible for US military assistance, in an attempt to end this practice.[176]

Treaties ratified

The U.S. has signed and ratified the following human rights treaties:

- International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) (ratified with 5 reservations, 5 understandings, and 4 declarations.)[177]

- Optional protocol on the involvement of children in armed conflict

- International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination

- Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment

- Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees[178]

- Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the Sale of Children, Child Prostitution and Child Pornography[179]

Non-binding documents voted for:

International Bill of Rights

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) are the legal treaties that enshrine the rights which are outlined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Together, and along with the first and second optional protocols of the ICCPR they constitute the International bill of rights[181][182] The US has not ratified the ICESCR or either of the optional protocols of the ICCPR.

The US's ratification of the ICCPR was done with five reservations – or limits – on the treaty, 5 understandings and 4 declarations. Among these is the rejection of sections of the treaty which prohibit capital punishment.[183][184] Included in the Senate's ratification was the declaration that "the provisions of Article 1 through 27 of the Covenant are not self-executing",[185] and in a Senate Executive Report stated that the declaration was meant to "clarify that the Covenant will not create a private cause of action in U.S. Courts."[186] This way of ratifying the treaty was criticized as incompatible with the Supremacy Clause by Louis Henkin.[187]

As a reservation that is "incompatible with the object and purpose" of a treaty is void as a matter of international law, Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, art. 19, 1155 U.N.T.S. 331 (entered into force Jan. 27, 1980) (specifying conditions under which signatory States can offer "reservations"), there is some issue as to whether the non-self-execution declaration is even legal under domestic law. At any rate, the United States is but a signatory in name only.

International Criminal Court

Further information: United States and the International Criminal CourtThe U.S. has not ratified the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC), which was drafted for prosecuting individuals above the authority of national courts in the event of accusations of genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and crime of aggression. Nations that have accepted the Rome Statute can defer to the jurisdiction of the ICC or must surrender their jurisdiction when ordered.

The US rejected the Rome Statute after its attempts to include the nation of origin as a party in international proceedings failed, and after certain requests were not met, including recognition of gender issues, "rigorous" qualifications for judges, viable definitions of crimes, protection of national security information that might be sought by the court, and jurisdiction of the UN Security Council to halt court proceedings in special cases.[188] Since the passage of the statute, the US has actively encouraged nations around the world to sign "bilateral immunity agreements" prohibiting the surrender of US personnel before the ICC[189] and actively attempted to undermine the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court.[10] The US Congress also passed a law, American Service-Members' Protection Act (ASPA) authorizing the use of military force to free any US personnel that are brought before the court rather than its own court system.[190][191] Human Rights Watch criticized the United States for removing itself from the Statute[192]

Judge Richard Goldstone, the first chief prosecutor at The Hague war crimes tribunal on the former Yugoslavia, echoed these sentiments saying:

I think it is a very backwards step. It is unprecedented which I think to an extent smacks of pettiness in the sense that it is not going to affect in any way the establishment of the international criminal court...The US have really isolated themselves and are putting themselves into bed with the likes of China, the Yemen and other undemocratic countries.[192]

While the US has maintained that it will "bring to justice those who commit genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes," its primary objections to the Rome Statute have revolved around the issues of jurisdiction and process. A US ambassador for War Crimes Issues to the UN Security Council said to the US Senate Foreign Relations Committee that because the Rome Statute requires only one nation to submit to the ICC, and that this nation can be the country in which an alleged crime was committed rather than defendant’s country of origin, U.S military personnel and US foreign peaceworkers in more than 100 countries could be tried in international court without the consent of the US. The ambassador states that "most atrocities are committed internally and most internal conflicts are between warring parties of the same nationality, the worst offenders of international humanitarian law can choose never to join the treaty and be fully insulated from its reach absent a Security Council referral. Yet multinational peacekeeping forces operating in a country that has joined the treaty can be exposed to the court's jurisdiction even if the country of the individual peacekeeper has not joined the treaty."[188]

Other treaties not signed or signed but not ratified

Where the signature is subject to ratification, acceptance or approval, the signature does not establish the consent to be bound. However, it is a means of authentication and expresses the willingness of the signatory state to continue the treaty-making process. The signature qualifies the signatory state to proceed to ratification, acceptance or approval. It also creates an obligation to refrain, in good faith, from acts that would defeat the object and the purpose of the treaty.[193]

The U.S. has not ratified the following international human rights treaties:[178]

- First Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR)

- Second Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, aiming at the abolition of the death penalty

- Optional Protocol to CEDAW

- Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture

- Convention relating to the Status of Refugees (1951)

- Convention Relating to the Status of Stateless Persons (1954)

- Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness (1961)

- International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families

The US has signed but not ratified the following treaties:

- Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) (signed but not ratified)

- Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) (signed but not ratified)

- International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (signed but not ratified)

Non-binding documents voted against:

- Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in September 2007.[194]

Inter-American human rights system

The US is a signatory to the 1948 American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man and has signed but not ratified the 1969 American Convention on Human Rights. It is a member of Inter-American Convention on the Granting of Political Rights to Women (1948). It does not accept the adjudicatory jurisdiction of the Costa Rica-based Inter-American Court of Human Rights.[195][196]

The US has not ratified any of the other regional human rights treaties of the Organization of American States,[178] which include:

- Protocol to the American Convention on Human Rights to Abolish the Death Penalty (1990)

- Additional Protocol to the American Convention on Human Rights in the Area of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights

- Inter-American Convention to Prevent and Punish Torture (1985)

- Inter-American Convention on the Prevention, Punishment and Eradication of Violence Against Women (1994)

- Inter-American Convention on Forced Disappearance of Persons (1994)

- Inter-American Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Persons with Disabilities

Coverage of violations in the media

Studies have found that the New York Times coverage of worldwide human rights violations is seriously biased, predominantly focusing on the human rights violations in nations where there is clear U.S. involvement, while having relatively little coverage of the human rights violations in other nations.[197][198] Amnesty International's Secretary General Irene Khan explains, "If we focus on the U.S. it's because we believe that the U.S. is a country whose enormous influence and power has to be used constructively ... When countries like the U.S. are seen to undermine or ignore human rights, it sends a very powerful message to others."[199]

Further assessments

According to Freedom in the World, an annual report by US based think-tank Freedom House, which rates political rights and civil liberties, in 2007, the United States was ranked "Free" (the highest possible rating), together with 92 other countries.

The Polity data series, which rate regime and authority characteristics, covering the years 1800-2004, has ranked the United States with the highest possible rating since 1871.[200]

According to the Economist Magazine's Democracy Index, the US ranks 17 out of 167 nations.

According to the annual Worldwide Press Freedom Index published by Reporters Without Borders, due to wartime restrictions the United States was ranked 53rd from the top in 2006 (out of 168), 44th in 2005.[201] 22nd in 2004,[202] 31st in 2003[203] and 17th in 2002.[204]

According to the annual Corruption Perceptions Index, which was published by Transparency International, the United States was ranked 20th from the top least corrupt in 2006 (out of 163), 17th in 2005, 18th in 2003, and 16th in 2002.

According to the annual Privacy International index of 2007, the United States was ranked an "endemic surveillance society", scoring only 1.5 out of 5 privacy points.[205]

According to the Gallup International Millennium Survey, the United States ranked 23rd in citizens' perception of human rights observance when its citizens were asked, "In general, do you think that human rights are being fully respected, partially respected or are they not being respected at all in your country?"[206]

Other issues

In the aftermath of the devastation caused by Hurricane Katrina, criticism by some groups commenting on human rights issues was made regarding the recovery and reconstruction issues[207][208] The American Civil Liberties Union and the National Prison Project documented mistreatment of the prison population during the flooding,[209][210] while United Nations Special Rapporteur Doudou Diène delivered a 2008 report on such issues.[211] The United States was elected in 2009 to sit on the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC),[212] which the U.S. State Department had previously asserted had lost its credibility by its prior stances[213] and lack of safeguards against severe human rights violators taking a seat.[214] In 2006 and 2007, the UNHCR and Martin Scheinin were critical of the United States regard permitting executions by lethal injection, housing children in adult jails, subjecting prisoners to prolonged isolation in supermax prisons, using enhanced interrogation techniques and domestic poverty gaps.[215][216][217][218]

See also

Criticism of the US Human rights record

- Human Rights Record of the United States, Report prepared by the People's Republic of China

US Human rights abuses

-

- Human experimentation in the United States

Organizations involved in US human rights

People involved in US human rights

Notable comments on Human Rights

-

- Four Freedoms, A speech made by U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt

- Moynihan's law

References

- ^ Ellis, Joseph J. (1998) [1996]. American Sphinx: The Character of Thomas Jefferson. Vintage Books. p. 63. ISBN 0679764410.

- ^ Lauren, Paul Gordon (2007). "A Human Rights Lens on U.S. History: Human Rights at Home and Human Rights Abroad". In Soohoo, Cynthia; Albisa, Catherine; Davis, Martha F.. Bringing Human Rights Home: Portraits of the Movement. III. Praeger Publishers. p. 4. ISBN 0275988244.

- ^ Brennan, William, J., ed. Schwartz, Bernard, The Burger Court: counter-revolution or confirmation?, Oxford University Press US, 1998,ISBN 0-19-512259-3, page 10