- Education in the United States

-

Education in The United States of America

U.S. Department of Education Secretary

Deputy SecretaryArne Duncan

Anthony MillerNational education budget (2007) Budget $972 billion (public and private, all levels)[1] General Details Primary Languages English System Type Federal, state, private Literacy Male 99%[2] Female 99%[2] Enrollment Total 81.5 million Primary 37.9 million1 Secondary 26.1 million (2006–2007) Post Secondary 17.5 million 2 Attainment Secondary diploma 85% Post-secondary diploma 27% 1 Includes kindergarten

2 Includes graduate schoolEducation in the United States is mainly provided by the public sector, with control and funding coming from three levels: federal, state, and local. Child education is compulsory.

Public education is universally available. School curricula, funding, teaching, employment, and other policies are set through locally elected school boards with jurisdiction over school districts with many directives from state legislatures. School districts are usually separate from other local jurisdictions, with independent officials and budgets. Educational standards and standardized testing decisions are usually made by state governments.

The ages for compulsory education vary by state. It begins from ages five to eight and ends from ages fourteen to eighteen.[3]

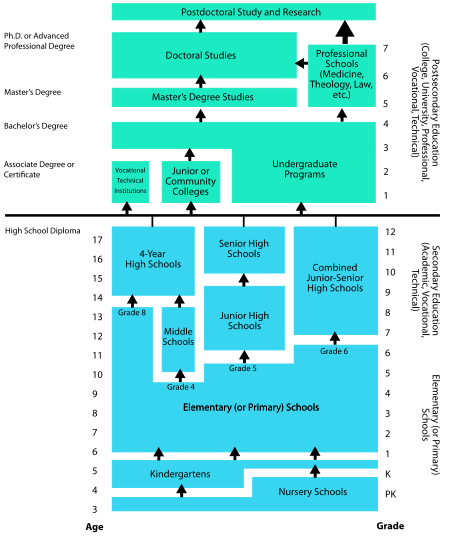

Compulsory education requirements can generally be satisfied by educating children in public schools, state-certified private schools, or an approved home school program. In most public and private schools, education is divided into three levels: elementary school, middle school (sometimes called junior high school), and high school (sometimes referred to as secondary education). In almost all schools at these levels, children are divided by age groups into grades, ranging from kindergarten (followed by first grade) for the youngest children in elementary school, up to twelfth grade, the final year of high school. The exact age range of students in these grade levels varies slightly from area to area.

Post-secondary education, better known as "college" in the United States, is generally governed separately from the elementary and high school system, and is described in a separate section below.

History

Main article: History of education in the United StatesStatistics

In the year 2000, there were 76.6 million students enrolled in schools from kindergarten through graduate schools. Of these, 72 percent aged 12 to 17 were judged academically "on track" for their age (enrolled in school at or above grade level). Of those enrolled in compulsory education, 5.2 million (10.4 percent) were attending private schools.

Among the country's adult population, over 85 percent have completed high school and 27 percent have received a bachelor's degree or higher. The average salary for college or university graduates is greater than $51,000, exceeding the national average of those without a high school diploma by more than $23,000, according to a 2005 study by the U.S. Census Bureau.[4] The 2010 unemployment rate for high school graduates was 10.8%; the rate for college graduates was 4.9%.[5]

The country has a reading literacy rate at 99% of the population over age 15,[6] while ranking below average in science and mathematics understanding compared to other developed countries.[7] In 2008, there was a 77% graduation rate from high school, below that of most developed countries.[8]

The poor performance has pushed public and private efforts such as the No Child Left Behind Act. In addition, the ratio of college-educated adults entering the workforce to general population (33%) is slightly below the mean of other developed countries (35%)[9] and rate of participation of the labor force in continuing education is high.[10] A 2000s study by Jon Miller of Michigan State University concluded that "A slightly higher proportion of American adults qualify as scientifically literate than European or Japanese adults".[11]

School grades

Most children enter the public education system around ages five or six. The American school year traditionally begins in August or September, after the traditional summer recess. Children are assigned into year groups known as grades, beginning with preschool, followed by kindergarten and culminating in twelfth grade. Children customarily advance together from one grade to the next as a single cohort or "class" upon reaching the end of each school year in May or June, although developmentally disabled children may be held back a grade and gifted children may skip ahead early to the next grade.[citation needed]

The American educational system comprises 12 grades of study over 12 calendar years of primary and secondary education before graduating and becoming eligible for college admission.[12] After pre-kindergarten and kindergarten, there are five years in [12] primary school (normally known as elementary school). After completing five grades, the student will enter junior high or middle school and then high school to get the high school diploma.[12]

The U.S. uses ordinal numbers for naming grades, unlike Canada and Australia where cardinal numbers are preferred. Thus, Americans are more likely to say "First Grade" rather than "Grade One". Typical ages and grade groupings in public and private schools may be found through the U.S. Department of Education.[13] Many different variations exist across the country.

Elementary school Preschool 4–5 Kindergarten 5–6 1st Grade 6–7 2nd Grade 7–8 3rd Grade 8–9 4th Grade 9–10 5th Grade 10-11 Middle school 6th Grade 11–12 7th Grade 12–13 8th Grade 13–14 High school 9th Grade (Freshman) 14-15 10th Grade (Sophomore) 15-16 11th Grade (Junior) 16-17 12th Grade (Senior) 17-18 Post-secondary education Tertiary education (College or University) Ages vary, but often 18–23

(Freshman, Sophomore, Junior and Senior years)Vocational education Ages vary Graduate education Ages vary Adult education Ages vary Students completing high school may apply to attend an undergraduate school. This may be a community college (one that offers two-year degrees, usually to prepare students to transfer to state universities), liberal arts college (one that concentrates on undergraduate education), or part of a larger research university.

The course of study is called the "major", which comprises the main or special subjects. However, students are not locked into a major upon admission—usually, a major is chosen by the second year of college, and changing majors is frequently possible depending on how the credits work out, unlike British tertiary education. Universities are either public (state-sponsored, such as Ohio State University or University of Georgia) or private such as Harvard or Swarthmore.

Students may choose to continue onto graduate school for a master's or Ph.D, or to a first professional degree program. A master's degree requires an additional two years of specialized study; a doctoral degree (Ph.D.) usually takes some years, although exactly how long depends on the time required to prepare the doctoral dissertation. First professional degrees have a more structured program than the typical Ph.D. program. The standard time required for a first professional degree is three or four years; for example, law school is a three-year program, while medical, dental, and veterinary schools are four-year programs.[citation needed]

Preschool

There are no mandatory public prekindergarten or crèche programs in the United States. The federal government funds the Head Start preschool program for children of low-income families, but most families are responsible for finding preschool or childcare.[citation needed]

In the large cities, there are sometimes preschools catering to the children of the wealthy. Because some wealthy families see these schools as the first step toward the Ivy League, there are even counselors who specialize in assisting parents and their toddlers through the preschool admissions process.[14] Increasingly, a growing body of preschools are adopting international standards such as the International Preschool Curriculum[15]

Student health

According to the National Association of School Nurses, 17% of students are considered obese and 32% are overweight.[16]

Elementary and secondary education

Schooling is compulsory for all children in the United States, but the age range for which school attendance is required varies from state to state. Most children begin elementary education with kindergarten (usually five to six years old) and finish secondary education with twelfth grade (usually eighteen years old). In some cases, pupils may be promoted beyond the next regular grade. Some states allow students to leave school between 14–17 with parental permission, before finishing high school; other states require students to stay in school until age 18[17]

Educational attainment in the United States, Age 25 and Over (2009)[18] Education Percentage High school graduate 86.68% Some college 55.60% Associates and/or Bachelor's degree 38.54% Master's degree 7.62% Doctorate or professional degree 2.94% Most parents send their children to either a public or private institution. According to government data, one-tenth of students are enrolled in private schools. Approximately 85% of students enter the public schools,[19] largely because they are tax-subsidized (tax burdens by school districts vary from area to area).

There are more than 14,000 school districts in the country.[20]

More than $500 billion is spent each year on primary and secondary education.[20]

Most states require that their school districts within the state teach for 180 days a year.[21]

Parents may also choose to educate their own children at home; 1.7% of children are educated in this manner.[19]

Nearly 6.2 million students between the ages of 16 and 24 in 2007 dropped out of high school, including nearly three of 10 Hispanics.[22]

The issue of high-school drop-outs is considered important to address as the incarceration rate for African-American male high school dropouts is about 50 (fifty) times the national average.[23]

In 1971, the Supreme Court ruled unanimously that forced busing of students may be ordered to achieve racial desegregation.[24] This ruling resulted in a white flight from the inner cities which largely diluted the intent of the order. This flight had other, non-educational ramifications as well. Integration took place in most schools though de facto segregation often determined the composition of the student body. By the 1990s, most areas of the country have been released from mandatory busing.

In 2010, there were 3,823,142 teachers in public, charter, private, and Catholic elementary and secondary schools. They taught a total of 55,203,000 students, who attended one of 132,656 schools.[25]

States do not require proper reporting from their school districts to allow analysis of efficiency of return on investment. The Center for American Progress, called a "left-leaning think tank", commends Florida and Texas as the only two states that provides annual school-level productivity evaluations which report to the public how well school funds are being spent at the local level. This allows for comparison of school districts within a state.[26][27]

In 2010, American students rank 17th in the world. The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development says that this is due to focusing on the low end of performers. All of the recent gains have been made, deliberately, at the low end of the socioeconomic scale and among the lowest achievers. The country has been outrun, the study says, by other nations because the US has not done enough to encourage the highest achievers.[28]

About half the states encourage schools to recite the Pledge of Allegiance to the flag.[29]

Teachers worked from about 35 to 46 hours a week in a survey taken in 1993.[30]

Transporting students to and from school is a major concern for most school districts. School buses provide the largest mass transit program in the country; 8.8 billion trips per year. Non-school transit buses give 5.2 billion trips annually. 440,000 yellow school buses carry over 24 million students to and from school.[31]

School start times are computed with busing in mind. There are often three start times; for elementary, for middle/junior high, and for high school. One school district computed its cost per bus (without the driver) at $20,575 annually. It assumed a model where the average driver drove 80 miles per day. A driver was presumed to cost $.62 per mile (1.6 km). Elementary schools started at 7:30, middle schools/junior high school started at 8:15 and senior high schools at 9:00. While elementary school started earlier, they also get out earlier, at 2:25; middle schools at 3:10 and senior high schools at 3:55.[32] All school districts establish their own times and means of transportation within guidelines set forth by their own state.

Elementary school

Main article: Primary education in the United StatesHistorically, in the United States, local public control (and private alternatives) have allowed for some variation in the organization of schools. Elementary school includes kindergarten through fifth grade (or sometimes, to fourth grade, sixth grade or eighth grade). In elementary school, basic subjects are taught, and students often remain in one or two classrooms throughout the school day, with the exceptions of physical education ("P.E." or "gym"), library, music, and art classes. There are (as of 2001) about 3.6 million children in each grade in the United States.[33]

Typically, the curriculum in public elementary education is determined by individual school districts. The school district selects curriculum guides and textbooks that are reflective of a state's learning standards and benchmarks for a given grade level.[34] Learning Standards are the goals by which states and school districts must meet adequate yearly progress (AYP) as mandated by No Child Left Behind (NCLB). This description of school governance is simplistic at best, however, and school systems vary widely not only in the way curricular decisions are made but also in how teaching and learning take place. Some states and/or school districts impose more top-down mandates than others. In others, teachers play a significant role in curriculum design and there are few top-down mandates. Curricular decisions within private schools are made differently than they are in public schools, and in most cases without consideration of NCLB.

Public Elementary School teachers typically instruct between twenty and thirty students of diverse learning needs. A typical classroom will include children with a range of learning needs or abilities, from those identified as having special needs of the kinds listed in the Individuals with Disabilities Act IDEA to those that are cognitively, athletically or artistically gifted. At times, an individual school district identifies areas of need within the curriculum. Teachers and advisory administrators form committees to develop supplemental materials to support learning for diverse learners and to identify enrichment for textbooks. Many school districts post information about the curriculum and supplemental materials on websites for public access.[35]

Each local school district gives each teacher a book to give to the students for each subject, and brief overviews of what the teacher are expected to teach.[citation needed] In general, a student learns basic arithmetic and sometimes rudimentary algebra in mathematics, English proficiency (such as basic grammar, spelling, and vocabulary), and fundamentals of other subjects. Learning standards are identified for all areas of a curriculum by individual States, including those for mathematics, social studies, science, physical development, the fine arts, and reading.[34] While the concept of State Learning standards has been around for some time, No Child Left Behind has mandated that standards exist at the State level.

Elementary School teachers are trained with emphases on human cognitive and psychological development and the principles of curriculum development and instruction. Teachers typically earn either a Bachelors or Masters Degree in Early Childhood and Elementary Education. The teaching of social studies and science are often underdeveloped in elementary school programs. Some attribute this to the fact that elementary school teachers are trained as generalists; however, teachers attribute this to the priority placed on developing reading, writing and math proficiency in the elementary grades and to the large amount of time needed to do so. Reading, writing and math proficiency greatly affect performance in social studies, science and other content areas. Certification standards for teachers are determined by individual states, with individual colleges and universities determining the rigor of the college education provided for future teachers. Some states require content area tests, as well as instructional skills tests for teacher certification in that state.[36]

The broad topic of Social Studies may include key events, documents, understandings, and concepts in American history, and geography, and in some programs, state or local history and geography. Topics included under the broader term "science" vary from the physical sciences such as physics and chemistry, through the biological sciences such as biology, ecology, and physiology. Most States have predetermined the number of minutes that will be taught within a given content area. Because No Child Left Behind focuses on reading and math as primary targets for improvement, other instructional areas have received less attention.[37] There is much discussion within educational circles about the justification and impact of having curricula that place greater emphasis on those topics (reading, writing and math) that are specifically tested for improvement.[38]

Secondary education

Main article: Secondary education in the United StatesAs part of education in the United States, secondary education usually covers grades 6 through 9 or 10 through 12.

Junior and senior high school

Middle school and Junior high school include the grade levels intermediate between elementary school and senior high school. "Middle school" usually includes sixth, seventh and eighth grade; "Junior high" typically includes seventh through ninth grade. The range defined by either is often based on demographic factors, such as an increase or decrease in the relative numbers of younger or older students, with the aim of maintaining stable school populations.[39] At this time, students are given more independence, moving to different classrooms for different subjects, and being allowed to choose some of their class subjects (electives). Usually, starting in ninth grade, grades become part of a student’s official transcript. Future employers or colleges may want to see steady improvement in grades and a good attendance record on the official transcript. Therefore, students are encouraged to take much more responsibility for their education.[citation needed]

Senior high school is a school attended after junior high school. High school is often used instead of senior high school and distinguished from junior high school. High school usually runs either from 9th through 12th, or 10th through 12th grade. The students in these grades are commonly referred to as freshmen (grade 9), sophomores (grade 10), juniors (grade 11) and seniors (grade 12).

Basic curricular structure

Generally, at the high school level, students take a broad variety of classes without special emphasis in any particular subject. Curricula vary widely in quality and rigidity; for example, some states consider 65 (on a 100-point scale) a passing grade, while others consider it to be as low as 60 or as high as 75.[citation needed] Students are required to take a certain minimum number of mandatory subjects, but may choose additional subjects ("electives") to fill out their required hours of learning.

The following minimum courses of study in mandatory subjects are required in nearly all U.S. high schools:

- Science (usually three years minimum, normally biology, chemistry and physics)

- Mathematics (usually four years minimum, normally including algebra, geometry, pre-calculus, statistics, and even calculus)

- English (usually four years minimum, including literature, humanities, composition, oral languages, etc.)

- Social sciences (usually three years minimum, including various history, government/economics courses)[40]

- Physical education (at least two years)

Many states require a "health" course in which students learn about anatomy, nutrition, first aid, sexuality, drug awareness and birth control. Anti-drug use programs are also usually part of health courses. In many cases, however, options are provided for students to "test out" of this requirement or complete independent study to meet it. Foreign language and some form of art education are also a mandatory part of the curriculum in some schools.

Electives

Common types of electives include:

- Computers (word processing, programming, graphic design)

- Athletics (cross country, football, baseball, basketball, track and field, swimming, tennis, gymnastics, water polo, soccer, softball, wrestling, cheerleading, volleyball, lacrosse, ice hockey, field hockey, crew, boxing, skiing/snowboarding, golf, mountain biking)

- Career and Technical Education (Agriculture/Agriscience, Business/Marketing, Family and Consumer Science, Health Occupations, and Technology Education, including Publishing (journalism/student newspaper, yearbook/annual, literary magazine))

- Performing Arts/Visual Arts, (choir, band, orchestra, drama, art, ceramics, photography, and dance)

- Foreign languages (Spanish and French are common; Chinese, Latin, Ancient Greek, German, Italian, Arabic, and Japanese are less common)[41]

- Junior Reserve Officers' Training Corps

Advanced courses

Many high schools provide Advanced Placement (AP) or International Baccalaureate (IB) courses. These are special forms of honors classes where the curriculum is more challenging and lessons more aggressively paced than standard courses. AP or IB courses are usually taken during the 11th or 12th grade of high school, but may be taken as early as 9th grade.

Most post-secondary institutions take AP or IB exam results into consideration in the admissions process. Because AP and IB courses are intended to be the equivalent of the first year of college courses, post-secondary institutions may grant unit credit, which enables students to graduate earlier. Other institutions use examinations for placement purposes only: students are exempted from introductory course work but may not receive credit towards a concentration, degree, or core requirement. Institutions vary in the selection of examinations they accept and the scores they require to grant credit or placement, with more elite institutions tending to accept fewer examinations and requiring higher scoring. The lack of AP, IB, and other advanced courses in impoverished inner-city high schools is often seen as a major cause of the greatly differing levels of post-secondary education these graduates go on to receive, compared with both public and private schools in wealthier neighborhoods.

Also, in states with well-developed community college systems, there are often mechanisms by which gifted students may seek permission from their school district to attend community college courses full-time during the summer, and part-time during the school year. The units earned this way can often be transferred to one's university, and can facilitate early graduation. Early college entrance programs are a step further, with students enrolling as freshmen at a younger-than-traditional age.

Home schooling

Main article: Homeschooling in the United StatesIn 2007, approximately 1.5 million children were homeschooled, up 74% from 1999 when the U.S. Department of Education first started keeping statistics. This was 2.9% of all children.[42]

Many select moral or religious reasons for homeschooling their children. The second main category is "unschooling," those who prefer a non-standard approach to education.[42]

Most homeschooling advocates are wary of the established educational institutions for various reasons. Some are religious conservatives who see nonreligious education as contrary to their moral or religious systems, or who wish to add religious instruction to the educational curriculum (and who may be unable to afford a church-operated private school, or where the only available school may teach views contrary to those of the parents). Others feel that they can more effectively tailor a curriculum to suit an individual student’s academic strengths and weaknesses, especially those with singular needs or disabilities. Still others feel that the negative social pressures of schools (such as bullying, drugs, crime, sex, and other school-related problems) are detrimental to a child’s proper development. Parents often form groups to help each other in the homeschooling process, and may even assign classes to different parents, similar to public and private schools.

Opposition to homeschooling comes from varied sources, including teachers' organizations and school districts. The National Education Association, the largest labor union in the United States, has been particularly vocal in the past.[43] Opponents' stated concerns fall into several broad categories, including fears of poor academic quality, loss of income for the schools, and religious or social extremism, or lack of socialization with others. At this time, over half of states have oversight into monitoring or measuring the academic progress of home schooled students, with all but ten requiring some form of notification to the state.[44]

Grading scale

In schools in the United States children are continually assessed throughout the school year by their teachers, and report cards are issued to parents at varying intervals. Generally the scores for individual assignments and tests are recorded for each student in a grade book, along with the maximum number of points for each assignment. At any time, the total number of points for a student when divided by the total number of possible points produces a percent grade, which can be translated to a letter grade. Letter grades are often but not always used on report cards at the end of a marking period, although the current grade may be available at other times (particularly when an electronic grade book connected to an online service is in use). Although grading scales usually differ from school to school, the most common grade scale is letter grades—"A" through "F"—derived from a scale of 0–100 or a percentile. In some areas, Texas or Virginia for example, the "D" grade (or that between 70–60) is considered a failing grade. In other jurisdictions, such as Hawaii, a "D" grade is considered passing in certain classes, and failing in others.

Example Grading Scale A B C D F, E, I, N, or U + – + – + – + – 100–97 96–93 92–90 89–87 86–83 82–80 79–77 76–73 72–70 69–67 66–63 62–60 Below 60 Percent Standardized testing

See also: Test (student assessment)Under the No Child Left Behind Act, all American states must test students in public schools statewide to ensure that they are achieving the desired level of minimum education,[45] such as on the Regents Examinations in New York, or the Florida Comprehensive Assessment Test (FCAT), and the Massachusetts Comprehensive Assessment System (MCAS); students being educated at home or in private schools are not included. The act also requires that students and schools show "adequate yearly progress." This means they must show some improvement each year. When a student fails to make adequate yearly progress, No Child Left Behind mandates that remediation through summer school and/or tutoring be made available to a student in need of extra help.

During high school, students (usually in 11th grade) may take one or more standardized tests depending on their postsecondary education preferences and their local graduation requirements. In theory, these tests evaluate the overall level of knowledge and learning aptitude of the students. The SAT and ACT are the most common standardized tests that students take when applying to college. A student may take the SAT, ACT, or both depending upon the post-secondary institutions the student plans to apply to for admission. Most competitive schools also require two or three SAT Subject Tests, (formerly known as SAT IIs), which are shorter exams that focus strictly on a particular subject matter. However, all these tests serve little to no purpose for students who do not move on to post-secondary education, so they can usually be skipped without affecting one's ability to graduate.

Extracurricular activities

A major characteristic of American schools is the high priority given to sports, clubs and activities by the community, the parents, the schools and the students themselves. Extracurricular activities are educational activities not falling within the scope of the regular curriculum but under the supervision of the school. These activities can extend to large amounts of time outside the normal school day; home-schooled students, however, are not normally allowed to participate. Student participation in sports programs, drill teams, bands, and spirit groups can amount to hours of practices and performances. Most states have organizations that develop rules for competition between groups. These organizations are usually forced to implement time limits on hours practiced as a prerequisite for participation. Many schools also have non-varsity sports teams, however these are usually afforded less resources and attention.

Sports programs and their related games, especially football and/or basketball, are major events for American students and for larger schools can be a major source of funds for school districts. Schools may sell "spirit" shirts to wear to games; school stadiums and gymnasiums are often filled to capacity, even for non-sporting competitions.[citation needed]

High school athletic competitions often generate intense interest in the community. Inner city schools serving poor students are heavily scouted by college and even professional coaches, with national attention given to which colleges outstanding high school students choose to attend. State high school championship tournaments football and basketball attract high levels of public interest.[citation needed]

In addition to sports, numerous non-athletic extracurricular activities are available in American schools, both public and private. Activities include Quizbowl, musical groups, marching bands, student government, school newspapers, science fairs, debate teams, and clubs focused on an academic area (such as the Spanish Club) or cultural interests (such as Key Club).[citation needed]

Education of students with special needs

Main article: Special education in the United StatesCommonly known as special classes, are taught by teachers with training in adapting curricula to meet the needs of students with special needs.

According to the National Association of School Nurses, 5% of students in 2009 have a seizure disorder, another 5% have ADHD and 10% have mental or emotional problems.[16]

Educating children with disabilities

The federal law, Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) requires states to ensure that all government-run schools provide services to meet the individual needs of students with special needs, as defined by the law.[46] All students with special needs are entitled to a free and appropriate public education (FAPE).

Schools meet with the parents or guardians to develop an Individualized Education Program that determines best placement for the child. Students must be placed in the least restrictive environment (LRE) that is appropriate for the student's needs. Government-run schools that fail to provide an appropriate placement for students with special needs can be taken to due process wherein parents may formally submit their grievances and demand appropriate services for the child. Schools may be eligible for state and federal funding for the (sometimes large) costs of providing the necessary facilities and services.[citation needed]

Criticism

At-risk students (those with educational needs that aren't associated with a disability) are often placed in classes with students with minor emotional and social disabilities.[47] Critics assert that placing at-risk students in the same classes as these disabled students may impede the educational progress of both the at-risk and the disabled students.[citation needed] Some research has refuted this claim, and has suggested this approach increases the academic and behavioral skills of the entire student population.[48]

See also: Special educationPublic and private schools

In the United States, state and local government have primary responsibility for education. The Federal Department of Education plays a role in standards setting and education finance, and some military primary and secondary schools are run by the Department of Defense.[49]

K-12 students in most areas have a choice between free tax-funded public schools, or privately-funded private schools.[citation needed]

Public school systems are supported by a combination of local, state, and federal government funding. Because a large portion of school revenues come from local property taxes, public schools vary widely in the resources they have available per student. Class size also varies from one district to another. Curriculum decisions in public schools are made largely at the local and state levels; the federal government has limited influence. In most districts, a locally elected school board runs schools. The school board appoints an official called the superintendent of schools to manage the schools in the district. The largest public school system in the United States is in New York City, where more than one million students are taught in 1,200 separate public schools. Because of its immense size – there are more students in the system than residents in eight US states – the New York City public school system is nationally influential in determining standards and materials, such as textbooks.

Admission to individual public schools is usually based on residency. To compensate for differences in school quality based on geography, school systems serving large cities and portions of large cities often have "magnet schools" that provide enrollment to a specified number of non-resident students in addition to serving all resident students. This special enrollment is usually decided by lottery with equal numbers of males and females chosen. Some magnet schools cater to gifted students or to students with special interests, such as the sciences or performing arts.[50]

Private schools in the United States include parochial schools (affiliated with religious denominations), non-profit independent schools, and for-profit private schools. Private schools charge varying rates depending on geographic location, the school's expenses, and the availability of funding from sources, other than tuition. For example, some churches partially subsidize private schools for their members. Some people have argued that when their child attends a private school, they should be able to take the funds that the public school no longer needs and apply that money towards private school tuition in the form of vouchers. This is the basis of the school choice movement.[citation needed]

5,072,451 students attended 33,740 private elementary and secondary schools in 2007. 74.5% of these were Caucasian, non-Hispanic, 9.8% were African American, 9.6% were Hispanic. 5.4% were Asian or Pacific Islander, and .6% were American Indian. Average school size was 150.3 students. There were 456,266 teachers. The number of students per teacher was about 11. 65% of seniors in private schools in 2006-7 went on to attend a 4-year college.[51]

Private schools have various missions: some cater to college-bound students seeking a competitive edge in the college admissions process; others are for gifted students, students with learning disabilities or other special needs, or students with specific religious affiliations. Some cater to families seeking a small school, with a nurturing, supportive environment. Unlike public school systems, private schools have no legal obligation to accept any interested student. Admission to some private schools is often highly selective. Private schools also have the ability to permanently expel persistently unruly students, a disciplinary option not legally available to public school systems. Private schools offer the advantages of smaller classes, under twenty students in a typical elementary classroom, for example; a higher teacher/student ratio across the school day, greater individualized attention and in the more competitive schools, expert college placement services. Unless specifically designed to do so, private schools usually cannot offer the services required by students with serious or multiple learning, emotional, or behavioral issues. Although reputed to pay lower salaries than public school systems, private schools often attract teachers by offering high-quality professional development opportunities, including tuition grants for advanced degrees. According to elite private schools themselves, this investment in faculty development helps maintain the high quality program that they offer.

An August 17, 2000 article by the Chicago Sun-Times refers to the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Chicago Office of Catholic Schools as the largest private school system in the United States.[52]

College and university

Main article: Higher education in the United States Alumni Hall at Saint Anselm College

Alumni Hall at Saint Anselm College

Post-secondary education in the United States is known as college or university and commonly consists of four years of study at an institution of higher learning. There are 4,352 colleges, universities, and junior colleges in the country.[53] In 2008, 36% of enrolled students graduated from college in four years. 57% completed their undergraduate requirements in six years, at the same college they first enrolled in.[54] The U.S. ranks 10th among industrial countries for percentage of adults with college degrees.[5]

Like high school, the four undergraduate grades are commonly called freshman, sophomore, junior, and senior years (alternatively called first year, second year, etc.). Students traditionally apply for admission into colleges. Schools differ in their competitiveness and reputation; generally, the most prestigious schools are private, rather than public. Admissions criteria involve the rigor and grades earned in high school courses taken, the students' GPA, class ranking, and standardized test scores (Such as the SAT or the ACT tests). Most colleges also consider more subjective factors such as a commitment to extracurricular activities, a personal essay, and an interview. While colleges will rarely list that they require a certain standardized test score, class ranking, or GPA for admission, each college usually has a rough threshold below which admission is unlikely.[citation needed]

Once admitted, students engage in undergraduate study, which consists of satisfying university and class requirements to achieve a bachelor's degree in a field of concentration known as a major. (Some students enroll in double majors or "minor" in another field of study.) The most common method consists of four years of study leading to a Bachelor of Arts (B.A.), a Bachelor of Science (B.S.), or sometimes another bachelor's degree such as Bachelor of Fine Arts (B.F.A.), Bachelor of Social Work (B.S.W.), Bachelor of Engineering (B.Eng.,) or Bachelor of Philosophy (B.Phil.) Five-Year Professional Architecture programs offer the Bachelor of Architecture Degree (B.Arch.)

Professional degrees such as law, medicine, pharmacy, and dentistry, are offered as graduate study after earning at least three years of undergraduate schooling or after earning a bachelor's degree depending on the program. These professional fields do not require a specific undergraduate major, though medicine, pharmacy, and dentistry have set prerequisite courses that must be taken before enrollment.[citation needed]

Alexander Hall at Princeton University

Alexander Hall at Princeton University

Some students choose to attend a community college for two years prior to further study at another college or university. In most states, community colleges are operated either by a division of the state university or by local special districts subject to guidance from a state agency. Community colleges may award Associate of Arts (AA) or Associate of Science (AS) degree after two years. Those seeking to continue their education may transfer to a four-year college or university (after applying through a similar admissions process as those applying directly to the four-year institution, see articulation). Some community colleges have automatic enrollment agreements with a local four-year college, where the community college provides the first two years of study and the university provides the remaining years of study, sometimes all on one campus. The community college awards the associate's degree, and the university awards the bachelor's and master's degrees.[citation needed]

Graduate study, conducted after obtaining an initial degree and sometimes after several years of professional work, leads to a more advanced degree such as a master's degree, which could be a Master of Arts (MA), Master of Science (MS), Master of Business Administration (MBA), or other less common master's degrees such as Master of Education (MEd), and Master of Fine Arts (MFA). Some students pursue a graduate degree that is in between a master's degree and a doctoral degree called a Specialist in Education (Ed.S.).

After additional years of study and sometimes in conjunction with the completion of a master's degree and/or Ed.S. degree, students may earn a Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) or other doctoral degree, such as Doctor of Arts, Doctor of Education, Doctor of Theology, Doctor of Medicine, Doctor of Pharmacy, Doctor of Physical Therapy, Doctor of Osteopathy, Doctor of Podiatry Medicine, Doctor of Veterinary Medicine, Doctor of Psychology, or Juris Doctor. Some programs, such as medicine and psychology, have formal apprenticeship procedures post-graduation, such as residencies and internships, which must be completed after graduation and before one is considered fully trained. Other professional programs like law and business have no formal apprenticeship requirements after graduation (although law school graduates must take the bar exam to legally practice law in nearly all states).

Entrance into graduate programs usually depends upon a student's undergraduate academic performance or professional experience as well as their score on a standardized entrance exam like the Graduate Record Examination (GRE-graduate schools in general), the Medical College Admission Test (MCAT), or the Law School Admission Test (LSAT). Many graduate and law schools do not require experience after earning a bachelor's degree to enter their programs; however, business school candidates are usually required to gain a few years of professional work experience before applying. 8.9 percent of students receive postgraduate degrees. Most, after obtaining their bachelor's degree, proceed directly into the workforce.[55]

Cost

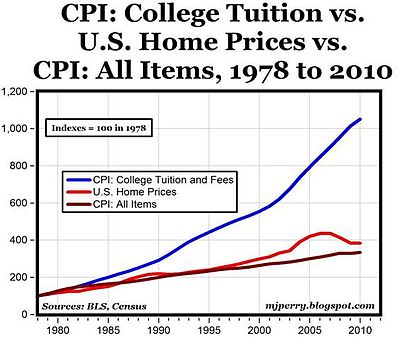

See also: College tuition in the United States Study comparing college revenue per student by tuition and state funding in 2008 dollars.[56]

Study comparing college revenue per student by tuition and state funding in 2008 dollars.[56]

The vast majority of students (up to 70 percent)[citation needed] lack the financial resources to pay tuition up front and must rely on student loans and scholarships from their university, the federal government, or a private lender. All but a few charity institutions cover all of the students' tuition, although scholarships (both merit-based and need-based) are widely available. Generally, private universities charge much higher tuition than their public counterparts, which rely on state funds to make up the difference. Because each state supports its own university system with state taxes, most public universities charge much higher rates for out-of-state students.[citation needed]

Annual undergraduate tuition varies widely from state to state, and many additional fees apply. In 2009, average annual tuition at a public university (for residents of the state) was $7,020.[54] Tuition for public school students from outside the state is generally comparable to private school prices, although students can often qualify for state residency after their first year. Private schools are typically much higher, although prices vary widely from "no-frills" private schools to highly specialized technical institutes. Depending upon the type of school and program, annual graduate program tuition can vary from $15,000 to as high as $50,000. Note that these prices do not include living expenses (rent, room/board, etc.) or additional fees that schools add on such as "activities fees" or health insurance. These fees, especially room and board, can range from $6,000 to $12,000 per academic year (assuming a single student without children).[57]

The mean annual Total Cost (including all costs associated with a full-time post-secondary schooling, such as tuition and fees, books and supplies, room and board), as reported by collegeboard.com for 2010:[57]

- Public University (4 years): $27,967 (per year)

- Private University (4 years): $40,476 (per year)

Total, four year schooling:

- Public University: $81,356

- Private University: $161,904

College costs are rising at the same time that state appropriations for aid are shrinking. This has led to debate over funding at both the state and local levels. From 2002 to 2004 alone, tuition rates at public schools increased over 14 percent, largely due to dwindling state funding. An increase of 6 percent occurred over the same period for private schools.[57] Between 1982 and 2007, college tuition and fees rose three times as fast as median family income, in constant dollars.[58]

From the US Census Bureau, the median salary of an individual who has only a high school diploma is $27,967; The median salary of an individual who has a bachelor's degree is $47,345.[59] Certain degrees, such as in engineering, typically result in salaries far exceeding high school graduates, whereas degrees in teaching and social work fall below.[citation needed]

The debt of the average college graduate for student loans in 2010 was $23,200.[60]

A 2010 study indicates that the "return on investment" for graduating from the top 1000 colleges exceeds 4% over a high school degree.[61]

To combat costs colleges have hired adjunct professors to teach. In 2008 these teachers cost about $1,800 per 3-credit class as opposed to $8,000 per class for a tenured professor. Two-thirds of college instructors were adjuncts. There are differences of opinion whether these adjuncts teach better or worse than regular professors. There is a suspicion that student evaluation of adjuncts, along with their subsequent continued employment, can lead to grade inflation.[62]

The status ladder

American college and university faculty, staff, alumni, students, and applicants monitor rankings produced by magazines such as U.S. News and World Report, Academic Ranking of World Universities, test preparation services such as The Princeton Review or another university itself such as the Top American Research Universities by the University of Florida's The Center.[63] These rankings are based on factors like brand recognition, selectivity in admissions, generosity of alumni donors, and volume of faculty research. In global university rankings, the US dominates more than half the top 50 places (27) and has a total of 72 institutions in the top 200 table under the Times Higher Education World University Rankings.[64] It has more than twice as many universities represented in the top 200 as its nearest rival, the United Kingdom, which has 29. A small percentage of students who apply to these schools gain admission.[65] Included among the top 20 institutions identified by ARWU in 2009 are six of the eight schools in the Ivy League; 4 of the 10 schools in the University of California system; the private Universities of Stanford, Chicago, and Johns Hopkins; the public Universities of Washington and Wisconsin; and the Massachusetts and California Institutes of Technology.[66]

Also renowned within the United States are the so-called "Little Ivies" and a number of prestigious liberal arts colleges. Certain public universities (sometimes referred to as "Public Ivies") are also recognized for their outstanding record in scholarship. Some of these institutions currently place among the elite in certain measurements of graduate education and research, especially among engineering and medical schools.[67][68]

Each state in the United States maintains its own public university system, which is always non-profit. The State University of New York and the California State University are the largest public higher education systems in the United States; SUNY is the largest system that includes community colleges, while CSU is the largest without. Most areas also have private institutions, which may be for-profit or non-profit. Unlike many other nations, there are no public universities at the national level outside of the military service academies.

Prospective students applying to attend four of the five military academies require, with limited exceptions, nomination by a member of Congress. Like acceptance to "top tier" universities, competition for these limited nominations is intense and must be accompanied by superior scholastic achievement and evidence of "leadership potential." The one academy that has never used congressional nomination, the United States Coast Guard Academy, is regularly cited as one of the country's most selective higher education institutions.[citation needed]

Aside from these aforementioned schools, academic reputations vary widely among the 'middle-tier' of American schools, (and even among academic departments within each of these schools.) Most public and private institutions fall into this 'middle' range. Some institutions feature honors colleges or other rigorous programs that challenge academically exceptional students, who might otherwise attend a 'top-tier' college.[69][70][71][72] Aware of the status attached to the perception of the college that they attend, students often apply to a range of schools. Some apply to a relatively prestigious school with a low acceptance rate, gambling on the chance of acceptance, and also apply to a "safety school",[73] to which they will (almost) certainly gain admission.

Lower status institutions include community colleges. These are primarily two-year public institutions, which individual states usually require to accept all local residents who seek admission, and offer associate's degrees or vocational certificate programs. Many community colleges have relationships with four-year state universities and colleges or even private universities that enable their students to transfer to these universities for a four-year degree after completing a two-year program at the community college.[citation needed]

Regardless of perceived prestige, many institutions feature at least one distinguished academic department, and most post-secondary American students attend one of the 2,400 four-year colleges and universities or 1,700 two-year colleges not included among the twenty-five or so 'top-tier' institutions.[74]

Criticism

A college economics professor has blamed "credential inflation" for the admission of so many unqualified students into college. He reports that the number of new jobs requiring college degrees is less than the number of college graduates.[5] The same professor reports that the more money that a state spends on higher education, the slower the economy grows, the opposite of long held notions.[5]

Reading and writing habits

Libraries have been considered important to educational goals.[75] Library books are more readily available to Americans than to people in Germany, Britain, France, the Netherlands, Austria and all the Mediterranean nations. The average American borrowed more library books in 2001 than his or her peers in Germany, Austria, Norway, Ireland, Luxembourg, France and throughout the Mediterranean.[76] Americans buy more books than people in Europe.[76]

There are more newspapers per capita in the US than anywhere in Europe outside Scandinavia, Switzerland and Luxembourg.[76]

Americans write relatively high number of books per capita.[76]

Contemporary education issues

See also: Education reformMajor educational issues in the United States center on curriculum, funding, and control. Of critical importance, because of its enormous implications on education and funding, is the No Child Left Behind Act.[45]

Tracking

See also: Tracking (education)Tracking is the practice of dividing students at the primary or secondary school level into separate classes, depending if the student is high, average, or low achievers. It also offers different curriculum paths for students headed for college and for those who are bound directly for the workplace or technical schools.[citation needed]

Curriculum issues

Curricula in the United States vary widely from district to district. Not only do schools offer a range of topics and quality, but private schools may include religious classes as mandatory for attendance. This raises the question of government funding vouchers in states with anti-Catholic Blaine Amendments in their constitution. This has produced camps of argument over the standardization of curricula and to what degree. These same groups often are advocates of standardized testing, which is mandated by the No Child Left Behind Act.

There is debate over which subjects should receive the most focus, with astronomy and geography among those cited as not being taught enough in schools.[77][78][79]

English in the classroom

A large issue facing curricula today is the use of the English language in teaching. English is spoken by over 95% of the nation, and there is a strong national tradition of upholding English as the de facto official language[citation needed]. Some 9.7 million children aged 5 to 17 primarily speak a language other than English at home. Of those, about 1.3 million children do not speak English well or at all.[80]

Attainment

Forty-four percent of college faculty believe that incoming students aren't ready for writing at the college level. Ninety percent of high school teachers believe exiting students are well-prepared.[81][82][83][84]

Drop out rates are a concern in American four year colleges. In New York, 54 percent of students entering four-year colleges in 1997 had a degree six years later — and even fewer Hispanics and blacks did.[85] 33 percent of the freshmen who enter the University of Massachusetts Boston graduate within six years. Less than 41 percent graduate from the University of Montana, and 44 percent from the University of New Mexico.[86]

Since the 1980s the number of educated Americans has continued to grow, but at a slower rate. Some have attributed this to an increase in the foreign born portion of the workforce. However, the decreasing growth of the educational workforce has instead been primarily due to slowing down in educational attainment of people schooled in the United States.[87]

Evolution in Kansas

In 1999 the School Board of the state of Kansas caused controversy when it decided to eliminate teaching of evolution in its state assessment tests.[88] Scientists from around the country demurred.[89] Many religious and family values groups, on the other hand, claimed that evolution is simply a theory in the colloquial sense,[90] and as such creationist ideas should therefore be taught alongside it as an alternative viewpoint.[91] A majority supported teaching intelligent design and/or creationism in public schools.[92]

Violence and drug use

Violence is a problem in high schools, depending on the size and level of the school. Between 1996 and September 2003, at least 46 students and teachers were killed in 27 incidents involving the use of firearms. Information from the National Center for Education Statistics shows that, in 2001, students between the ages of 12 and 18 were the victims of 2 million crimes in US schools. 62% of the crimes were thefts. Between July 1999 and June 2000, 24 murders and 8 suicides took place in American schools.

Also in 2001, 47% of American high school students drank alcohol at least once; 5% drank right on school territory. 24% of high school students smoked marijuana, 5% smoking right at school. 29% of students who smoke marijuana obtain the drug at school.[93]

Sex education

Main article: Sex education in the United StatesAlmost all students in the U.S. receive some form of sex education at least once between grades 7 and 12; many schools begin addressing some topics as early as grades 4 or 5.[94] However, what students learn varies widely, because curriculum decisions are so decentralized. Many states have laws governing what is taught in sex education classes or allowing parents to opt out. Some state laws leave curriculum decisions to individual school districts.[95] For example, a 1999 study by the Guttmacher Institute found that most U.S. sex education courses in grades 7 through 12 cover puberty, HIV, STDs, abstinence, implications of teenage pregnancy, and how to resist peer pressure. Other studied topics, such as methods of birth control and infection prevention, sexual orientation, sexual abuse, and factual and ethical information about abortion, varied more widely.[96]

However, according to a 2004 survey, a majority of the 1001 parent groups polled wants complete sex education in the schools. The American people are heavily divided over the issue. Over 80% of polled parents agreed with the statement "Sex education in school makes it easier for me to talk to my child about sexual issues," while under 17% agreed with the statement that their children were being exposed to "subjects I don't think my child should be discussing." 10 percent believed that their children's sexual education class forced them to discuss sexual issues "too early." On the other hand, 49 percent of the respondents (the largest group) were "somewhat confident" that the values taught in their children's sex ed classes were similar to those taught at home, and 23 percent were less confident still. (The margin of error was plus or minus 4.7 percent.)[97]

Textbook review and adoption

In many localities in the United States, the curriculum taught in public schools is influenced by the textbooks used by the teachers. In some states, textbooks are selected for all students at the state level. Since states such as California and Texas represent a considerable market for textbook publishers, these states can exert influence over the content of the books.[98]

In 2010, the Texas Board of Education adopted new Social Studies standards that could potentially impact the content of textbooks purchased in other parts of the country. The deliberations that resulted in the new standards were partisan in nature and are said to reflect a conservative leaning in the view of United States history.[99]

As of January 2009, the four largest college textbook publishers in the United States were:

- Pearson Education (including such imprints as Addison-Wesley and Prentice Hall)

- Cengage Learning (formerly Thomson Learning)

- McGraw-Hill

- Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

Other US textbook publishers include:

- John Wiley & Sons

- Jones and Bartlett Publishers

- F. A. Davis Company

- W. W. Norton & Company

- SAGE Publications

- Flat World Knowledge

- Bookboon.com

Funding

Funding for K–12 schools

According to a 2005 report from the OECD, the United States is tied for first place with Switzerland when it comes to annual spending per student on its public schools, with each of those two countries spending more than $11,000 (in U.S. currency).[100] However, the United States is ranked 37th in the world in education spending as a percentage of gross domestic product. All but seven of the leading countries are in the third world; ranked high because of a low GDP.[101] U.S. public schools lag behind the schools of other developed countries in the areas of reading, math, and science.[102]

According to a 2007 article in The Washington Post, the Washington D.C. public school district spends $12,979 per student per year. This is the third highest level of funding per student out of the 100 biggest school districts in the U.S. According to the article, however, these schools are ranked last in the amount of funding spent on teachers and instruction, and first on the amount spent on administration. The school district has produced outcomes that are lower than the national average. In reading and math, the district's students score the lowest among 11 major school districts – even when poor children are compared with other poor children. 33% of poor fourth graders in the U.S. lack basic skills in math, but in Washington D.C., it's 62%.[103] In 2004, the U.S. Congress set up a voucher program for low income minority students in Washington D.C. to attend private schools. The vouchers were $7,500 per student per year. The parents said their children were receiving a much better education from the private schools. In 2007, Washington D.C. non-voting delegate Eleanor Holmes Norton said she wanted the voucher program to be eliminated, and that the public schools needed more money.[104] Secretary of Education Arne Duncan supports retaining vouchers for the district only, as do some DC parent groups.[105][106]

According to a 2006 study by the Goldwater Institute, Arizona's public schools spend 50% more per student than Arizona's private schools. The study also says that while teachers constitute 72% of the employees at private schools, they make up less than half of the staff at public schools. According to the study, if Arizona's public schools wanted to be like private schools, they would have to hire approximately 25,000 more teachers, and eliminate 21,210 administration employees.[107]

During the 2006–2007 school year, a private school in Chicago founded by Marva Collins to teach low income minority students charged $5,500 for tuition, and parents said that the school did a much better job than the Chicago public school system.[108] However, Collins' school was forced to close in 2008 due to lack of sufficient enrollment and funding.[109] Meanwhile, during the 2007–2008 year, Chicago public school officials claimed that their budget of $11,300 per student was not enough.[110]

In 1985 in Kansas City, Missouri, a judge ordered the school district to raise taxes and spend more money on public education. Spending was increased so much, that the school district was spending more money per student than any of the country's other 280 largest school districts with a charge to "dream" of the possibilities and to make them happen. Although this very high level of spending continued for more than a decade, there was no improvement in the school district's academic performance.[111][112]

Public school defenders answer that both of these examples are misleading, as the task of educating students is easier in private schools, which can expel or refuse to accept students who lag behind their peers in academic achievement or behavior, while public schools have no such recourse and must continue to attempt to educate these students. For this reason, comparisons of the cost of education in public schools to that of private schools is misleading; private school education can be accomplished with less funding because in most cases they educate those students who are easiest to teach.[113]

But not in all cases. For example, Marva Collins created her low cost private school specifically for the purpose of teaching low income African American children whom the public school system had labeled as being "learning disabled".[114] One article about Marva Collins' school stated, "Working with students having the worst of backgrounds, those who were working far below grade level, and even those who had been labeled as 'unteachable,' Marva was able to overcome the obstacles. News of third grade students reading at ninth grade level, four-year-olds learning to read in a few months, outstanding test scores, disappearance of behavioral problems, second-graders studying Shakespeare, and other incredible reports, astounded the public." [115]

According to a 1999 article by William J. Bennett, former U.S. Secretary of Education, increased levels of spending on public education have not made the schools better. Among many other things, the article cites the following statistics:[116]

- Between 1960 and 1995, U.S. public school spending per student, adjusted for inflation, increased by 212%.

- In 1994, less than half of all U.S. public school employees were teachers.

- Out of 21 industrialized countries, U.S. 12th graders ranked 19th in math, 16th in science, and last in advanced physics.

A 2008 report[117] by The Heritage Foundation provides the following chart based on data[118][119] from the US Department of Education indicating no real improvement in reading scores, while per student expenditure more than doubles from $4,060 in 1970 to $9,266 in 2005 ($20,436.03 adjusted for inflation since 1970).[120][121]

Other commentators have suggested that the public school system has exhibited signs of success. SAT scores have risen consistently over the past decades, despite the fact that the pool of students taking the test has increased from an academic elite to a much more representative sampling of the population. Commentators have suggested that this increase in scores, coming as it does at a time when more students have started to take the test and the public schooling system has faced ever-increasing challenge, suggests that the US educational system is much more effective than is commonly believed, and that the negative cast common in public perception is due to negative propaganda disseminated by elements with a personal interest in discrediting or weakening public education.[122]

Funding for schools in the United States is complex. One current controversy stems much from the No Child Left Behind Act. The Act gives the Department of Education the right to withhold funding if it believes a school, district, or even a state is not complying and is making no effort to comply. However, federal funding accounts for little of the overall funding schools receive. The vast majority comes from the state government and in some cases from local property taxes. Various groups, many of whom are teachers, constantly push for more funding. They point to many different situations, such as the fact that in many schools funding for classroom supplies is so inadequate that teachers, especially those at the elementary level, must supplement their supplies with purchases of their own.[123]

Property taxes as a primary source of funding for public education have become highly controversial, for a number of reasons. First, if a state's population and land values escalate rapidly, many longtime residents may find themselves paying property taxes much higher than anticipated. In response to this phenomenon, California's citizens passed Proposition 13 in 1978, which severely restricted the ability of the Legislature to expand the state's educational system to keep up with growth. Some states, such as Michigan, have investigated or implemented alternate schemes for funding education that may sidestep the problems of funding based mainly on property taxes by providing funding based on sales or income tax. These schemes also have failings, negatively impacting funding in a slow economy.[124]

One of the biggest debates in funding public schools is funding by local taxes or state taxes. The federal government supplies around 8.5% of the public school system funds, according to a 2005 report by the National Center for Education Statistics. The remaining split between state and local governments averages 48.7 percent from states and 42.8 percent from local sources. However, the division varies widely. In Hawaii local funds make up 1.7 percent, while state sources account for nearly 90.1 percent.[125]

The most expensive school in the United States was constructed by the Los Angeles Unified School District in 2010. It cost $578 million; served 4,200 K–12 students.[126]

Judicial intervention

The reliance on local funding sources has led to a long history of court challenges about how states fund their schools. These challenges have relied on interpretations of state constitutions after a U.S. Supreme Court ruling that school funding was not a matter of the U.S. Constitution (San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez, 411 U.S. 1 (1973)). The state court cases, beginning with the California case of Serrano v. Priest, 5 Cal.3d 584 (1971), were initially concerned with equity in funding, which was defined in terms of variations in spending across local school districts. More recently, state court cases have begun to consider what has been called 'adequacy.' These cases have questioned whether the total amount of spending was sufficient to meet state constitutional requirements. Perhaps the most famous adequacy case is Abbott v. Burke, 100 N.J. 269, 495 A.2d 376 (1985), which has involved state court supervision over several decades and has led to some of the highest spending of any U.S. districts in the so-called Abbott districts. The background and results of these cases are analyzed in a book by Eric Hanushek and Alfred Lindseth. [127] That analysis concludes that funding differences are not closely related to student outcomes and thus that the outcomes of the court cases have not led to improved policies.

Funding for college

At the college and university level student loan funding is split in half; half is managed by the Department of Education directly, called the Federal Direct Student Loan Program (FDSLP). The other half is managed by commercial entities such as banks, credit unions, and financial services firms such as Sallie Mae, under the Federal Family Education Loan Program (FFELP). Some schools accept only FFELP loans; others accept only FDSLP. Still others accept both, and a few schools will not accept either, in which case students must seek out private alternatives for student loans.[128]

Charter schools

Main article: Charter schoolThe charter-school movement was born in 1990. Charter schools have spread rapidly in the United States, members, parents, teachers, and students" to allow for the "expression of diverse teaching philosophies and cultural and social life styles." [129]

Affirmative action

In 2003 a Supreme Court decision concerning affirmative action in universities allowed educational institutions to consider race as a factor in admitting students, but ruled that strict point systems are unconstitutional.[130] Opponents of racial affirmative action argue that the program actually benefits middle- and upper-class people of color at the expense of lower class European Americans and Asian Americans.[131] Prominent African American academics Henry Louis Gates and Lani Guinier, while favoring affirmative action, have argued that in practice, it has led to recent black immigrants and their children being greatly overrepresented at elite institutions, at the expense of the historic African American community made up of descendants of slaves.[132] In 2006, Jian Li, a Chinese undergraduate at Yale University, filed a civil rights complaint with the Office for Civil Rights against Princeton University, claiming that his race played a role in their decision to reject his application for admission.[133]

See also: Affirmative action in the United StatesControl

There is some debate about where control for education actually lies. Education is not mentioned in the constitution of the United States. In the current situation, the state and national governments have a power-sharing arrangement, with the states exercising most of the control. Like other arrangements between the two, the federal government uses the threat of decreased funding to enforce laws pertaining to education.[49] Furthermore, within each state there are different types of control. Some states have a statewide school system, while others delegate power to county, city or township-level school boards. However, under the Bush administration, initiatives such as the No Child Left Behind Act have attempted to assert more central control in a heavily decentralized system.

Many cities have their own school boards everywhere in the United States. With the exception of cities, outside the northeast U.S. school boards are generally constituted at the county level.

The U.S. federal government exercises its control through the U.S. Department of Education. Educational accreditation decisions are made by voluntary regional associations. Schools in the 50 states, the District of Columbia, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Guam, and the Northern Mariana Islands, teach in English, while schools in the commonwealth of Puerto Rico teach in Spanish. Nonprofit private schools are widespread, are largely independent of the government, and include secular as well as parochial schools.

International comparison

In the OECD's Programme for International Student Assessment 2003, which emphasizes problem solving, American 15 year olds ranked 24th of 38 in mathematics, 19th of 38 in science, 12th of 38 in reading, and 26th of 38 in problem solving.[134] In the 2006 assessment, the U.S. ranked 35th out of 57 in mathematics and 29th out of 57 in science. Reading scores could not be reported due to printing errors in the instructions of the U.S. test booklets. U.S. scores were behind those of most other developed nations.[135]

However, the picture changes when low achievers in the U.S. are broken out by race. White and Asian students in the United States are generally among the best-performing pupils in the world; black and Hispanic students in the U.S. have very high rates of low achievement.[136][137]

US fourth and eighth graders tested above average on the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study tests, which emphasizes traditional learning.[138]

Educational attainment

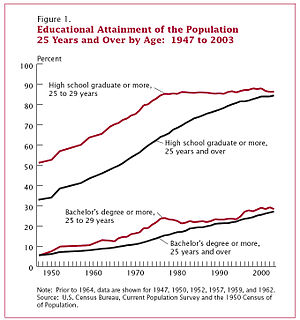

Main article: Educational attainment in the United States This graph shows the educational attainment since 1947.[139]

This graph shows the educational attainment since 1947.[139]

The rise of the high school movement in the beginning of the 20th century was unique in the United States, such that, high schools were implemented with property-tax funded tuition, openness, non-exclusivity, and were decentralized.

The academic curriculum was designed to provide the students with a terminal degree. The students obtained general knowledge (such as mathematics, chemistry, English composition, etc.) applicable to the high geographic and social mobility in the United States. The provision of the high schools accelerated with the rise of the second industrial revolution. The increase in white collar and skilled blue-collar work in manufacturing was reflected in the demand for high school education.

In the 21st century, the educational attainment of the US population is similar to that of many other industrialized countries with the vast majority of the population having completed secondary education and a rising number of college graduates that outnumber high school dropouts. As a whole, the population of the United States is becoming increasingly more educated.[citation needed] Post-secondary education is valued very highly by American society and is one of the main determinants of class and status.[citation needed] As with income, however, there are significant discrepancies in terms of race, age, household configuration and geography.[139] Overall the households and demographics featuring the highest educational attainment in the United States are also among those with the highest household income and wealth. Thus, while the population of the US is becoming increasingly educated on all levels, a direct link between income and educational attainment remains.[139]

In 2007, Americans stood second only to Canada in the percentage of 35 to 64 year olds holding at least two-year degrees. Among 25 to 34 year olds, the country stands tenth. The nation stands 15 out of 29 rated nations for college completion rates, slightly above Mexico and Turkey.[58]

The U.S. Department of Education’s 2003 statistics suggest that 14% of the population – or 32 million adults – have very low literacy skills.[140]

A five-year, $14 million study of U.S. adult literacy involving lengthy interviews of U.S. adults, the most comprehensive study of literacy ever commissioned by the U.S. government,[141] was released in September 1993. It involved lengthy interviews of over 26,700 adults statistically balanced for age, gender, ethnicity, education level, and location (urban, suburban, or rural) in 12 states across the U.S. and was designed to represent the U.S. population as a whole. This government study showed that 21% to 23% of adult Americans were not "able to locate information in text", could not "make low-level inferences using printed materials", and were unable to "integrate easily identifiable pieces of information."[141]

According to a 2003 study by the US government, around 23% of Americans in California lack basic prose literacy skills.[142]

Health and safety

Many schools have nurses either full-time or part time to administer to students and to ensure that medication is taken as directed by their physician.[143]

For some high school grades and many elementary schools as well, a police officer, titled a "resource officer", or SRO (Security Resource Officer), is on site to screen students for firearms and to help avoid disruptions.[144][145][citation needed]

See also

- Academic grading in the United States

- ACT and SAT