- University

-

For other uses, see University (disambiguation).See also: College

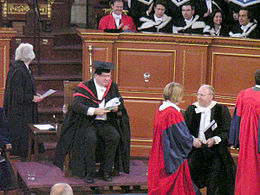

Degree ceremony at the University of Oxford. The Pro-Vice-Chancellor in MA gown and hood, Proctor in official dress and new Doctors of Philosophy in scarlet full dress. Behind them, a bedel, a Doctor and Bachelors of Arts and Medicine graduate.

Degree ceremony at the University of Oxford. The Pro-Vice-Chancellor in MA gown and hood, Proctor in official dress and new Doctors of Philosophy in scarlet full dress. Behind them, a bedel, a Doctor and Bachelors of Arts and Medicine graduate.

A university is an institution of higher education and research, which grants academic degrees in a variety of subjects. A university is an organisation that provides both undergraduate education and postgraduate education. The word university is derived from the Latin universitas magistrorum et scholarium, which roughly means "community of teachers and scholars."[1]

Contents

History

Definition

The original Latin word "universitas" was used at the time of emergence of urban town life and medieval guilds, to describe specialised "associations of students and teachers with collective legal rights usually guaranteed by charters issued by princes, prelates, or the towns in which they were located."[2] The original Latin word referred to degree-granting institutions of learning in Western Europe, where this form of legal organisation was prevalent, and from where the institution spread around the world. For non-related educational institutions of antiquity which did not stand in the tradition of the university and to which the term is only loosely and retrospectively applied, see ancient higher-learning institutions.

Academic freedom

An important idea in the definition of a university is the notion of academic freedom. The first documentary evidence of this comes from early in the life of the first university. The University of Bologna adopted an academic charter, the Constitutio Habita,[3] in 1158 or 1155,[4] which guaranteed the right of a traveling scholar to unhindered passage in the interests of education. Today this is claimed as the origin of "academic freedom".[5] This is now widely recognised internationally - on 18 September 1988 430 university rectors signed the Magna Charta Universitatum,[6] marking the 900th anniversary of Bologna's foundation. The number of universities signing the Magna Charta Universitatum continues to grow, drawing from all parts of the world.

Medieval universities

Main articles: Medieval university and List of medieval universities Area above the Old University of Bologna buildings, founded in 1088

Area above the Old University of Bologna buildings, founded in 1088

Prior to their formal establishment, many medieval universities were run for hundreds of years as Christian cathedral schools or monastic schools (Scholae monasticae), in which monks and nuns taught classes; evidence of these immediate forerunners of the later university at many places dates back to the 6th century AD.[7] The earliest universities were developed under the aegis of the Latin Church, usually from cathedral schools or by papal bull as studia generalia (n.b. The development of cathedral schools into universities actually appears to be quite rare, with the University of Paris being an exception — see Leff, Paris and Oxford Universities), later they were also founded by Kings (University of Naples Federico II, Charles University in Prague, Jagiellonian University in Kraków) or municipal administrations (University of Cologne, University of Erfurt). In the early medieval period, most new universities were founded from pre-existing schools, usually when these schools were deemed to have become primarily sites of higher education. Many historians state that universities and cathedral schools were a continuation of the interest in learning promoted by monasteries.[8]

The first universities with formally established guilds in Europe were the University of Bologna (1088), the University of Paris (c. 1150, later associated with the Sorbonne), the University of Oxford (1167), the University of Palencia (1208), the University of Cambridge (1209), the University of Salamanca (1218), the University of Montpellier (1220), the University of Padua (1222), the University of Naples Federico II (1224), the University of Toulouse (1229).,[9][10] the University of Siena (1240).

The University of Bologna began as a law school teaching the ius gentium or Roman law of peoples which was in demand across Europe for those defending the right of incipient nations against empire and church. Bologna’s special claim to Alma Mater Studiorum[clarification needed] is based on its autonomy, its awarding of degrees, and other structural arrangements, making it the oldest continuously operating institution[4] independent of kings, emperors or any kind of direct religious authority.[11][12]

The conventional date of 1088, or 1087 according to some,[13] records when a certain Irnerius commences teaching Emperor Justinian’s 6th century codification of Roman law, the Corpus Iuris Civilis, recently discovered at Pisa. Lay students arrived in the city from many lands entering into a contract to gain this knowledge, organising themselves into ‘Learning Nations’ of Hungarians, Greeks, North Africans, Arabs, Franks, Germans, Iberians etc. The students “had all the power … and dominated the masters”.[14][15]

In Europe, young men proceeded to university when they had completed their study of the trivium–the preparatory arts of grammar, rhetoric and dialectic or logic–and the quadrivium: arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy. (See Degrees of the University of Oxford for the history of how the trivium and quadrivium developed in relation to degrees, especially in anglophone universities).

Universities became popular all over Europe, as rulers and city governments began to create them to satisfy a European thirst for knowledge, and the belief that society would benefit from the scholarly expertise generated from these institutions. Princes and leaders of city governments perceived the potential benefit of having a scholarly expertise develop with the ability to address difficult problems and achieve desired ends. The emergence of humanism was essential to this understanding of the possible utility of universities as well as the revival of interest in knowledge gained from ancient Greek texts.[16]

The rediscovery of Aristotle's works - more than 3000 pages of it would eventually be translated - fuelled a spirit of inquiry into natural processes that had already begun to emerge in the 12th century. Some scholars believe that these works represented one of the most important document discoveries in Western intellectual history.[17] Richard Dales, for instance, calls the discovery of Aristotle's works “a turning point in the history of Western thought."[18] After Aristotle re-emerged, a community of scholars, primarily communicating in Latin, accelerated the process and practice of attempting to reconcile the thoughts of Greek antiquity, and especially ideas related to understanding the natural world, with those of the church. The efforts of this “scholasticism” were focused on applying Aristotelian logic and thoughts about natural processes to biblical passages and attempting to prove the viability of those passages through reason. This became the primary mission of lecturers, and the expectation of students.

The university culture developed differently in northern Europe than it did in the south, although the northern (primarily Germany, France and Great Britain) and southern universities (primarily Italy) did have many elements in common. Latin was the language of the university, used for all texts, lectures, disputations and examinations. Professors lectured on the books of Aristotle for logic, natural philosophy, and metaphysics; while Hippocrates, Galen, and Avicenna were used for medicine. Outside of these commonalities, great differences separated north and south, primarily in subject matter. Italian universities focused on law and medicine, while the northern universities focused on the arts and theology. There were distinct differences in the quality of instruction in these areas which were congruent with their focus, so scholars would travel north or south based on their interests and means. There was also a difference in the types of degrees awarded at these universities. English, French and German universities usually awarded bachelor's degrees, with the exception of degrees in theology, for which the doctorate was more common. Italian universities awarded primarily doctorates. The distinction can be attributed to the intent of the degree holder after graduation – in the north the focus tended to be on acquiring teaching positions, while in the south students often went on to professional positions.[19] The structure of Northern Universities tended to be modeled after the system of faculty governance developed at the University of Paris. Southern universities tended to be patterned after the student-controlled model begun at the University of Bologna.[20]

Although the university is widely regarded as "the European institution par excellence" in terms of its origins and characteristics,[21] some scholars have argued that early medieval universities were influenced by the religious Madrasah schools in Al-Andalus, the Emirate of Sicily, and the Middle East (during the Crusades).[22] Other scholars oppose this view[23] and argue that there is no actual evidence of the transmission of Arab scholarly methods discernible in medieval universities.[24]

Early Modern universities

See also: List of early modern universities in Europe and List of colonial universities in Latin AmericaDuring the Early Modern period (approximately late 1400s to 1800), the universities of Europe would see a tremendous amount of growth, productivity and innovative research. At the end of the Middle Ages, about 400 years after the first university was founded, there were twenty-nine universities spread throughout Europe. In the 15th century, twenty-eight new ones were created, with another eighteen added between 1500 and 1625.[25] This pace continued until by the end of the 18th century there were approximately 143 universities in Europe and Eastern Europe, with the highest concentrations in the German Empire (34), Italian countries (26), France (25), and Spain (23) – this was close to a 500% increase over the number of universities toward the end of the Middle Ages. This number does not include the numerous universities that disappeared, or institutions that merged with other universities during this time.[26] It should be noted that the identification of a university was not necessarily obvious during the Early Modern period, as the term is applied to a burgeoning number of institutions. In fact, the term “university” was not always used to designate a higher education institution. In Mediterranean countries, the term studium generale was still often used, while “Academy” was common in Northern European countries.[27]

The propagation of universities was not necessarily a steady progression, as the seventeenth century was rife with events that adversely effected university expansion. Many wars, and especially the Thirty Years' War, disrupted the university landscape throughout Europe at different times. War, plague, famine, regicide, and changes in religious power and structure often adversely affected the societies that provided support for universities. Internal strife within the universities themselves, such as student brawling and absentee professors, acted to destabilize these institutions as well. Universities were also reluctant to give up older curricula, and the continued reliance on the works of Aristotle defied contemporary advancements in science and the arts.[28] This era was also affected by the rise of the nation-state. As universities increasingly came under state control, or formed under the auspices of the state, the faculty governance model (begun by the University of Paris) became more and more prominent. Although the older student-controlled universities still existed, they slowly started to move toward this structural organization. Control of universities still tended to be independent, although university leadership was increasingly appointed by the state.[29]

Although the structural model provided by the University of Paris, where student members are controlled by faculty “masters,” provided a standard for universities, the application of this model took at least three different forms. There were universities that had a system of faculties whose teaching was centralized around a very specific curriculum; this model tended to train specialists. There was a collegiate or tutorial model based on the system at University of Oxford where teaching and organization was decentralized and knowledge was more of a generalist nature. There were also universities that combined these models, using the collegiate model but having a centralized organization.[30]

Early Modern universities initially continued the curriculum and research of the Middle Ages: natural philosophy, logic, medicine, theology, mathematics, astronomy (and astrology), law, grammar and rhetoric. Aristotle was prevalent throughout the curriculum, while medicine also depended on Galen and Arabic scholarship. The importance of humanism for changing this state-of-affairs cannot be underestimated.[31] Once humanist professors joined the university faculty, they began to transform the study of grammar and rhetoric through the studia humanitatis. Humanist professors focused on the ability of students to write and speak with distinction, to translate and interpret classical texts, and to live honorable lives.[32] Other scholars within the university were affected by the humanist approaches to learning and their linguistic expertise in relation to ancient texts, as well as the ideology that advocated the ultimate importance of those texts.[33] Professors of medicine such as Niccolò Leoniceno, Thomas Linacre and William Cop were often trained in and taught from a humanist perspective as well as translated important ancient medical texts. The critical mindset imparted by humanism was imperative for changes in universities and scholarship. For instance, Andreas Vesalius was educated in a humanist fashion before producing a translation of Galen, whose ideas he verified through his own dissections. In law, Andreas Alciatus infused the Corpus Juris with a humanist perspective, while Jacques Cujas humanist writings were paramount to his reputation as a jurist. Philipp Melanchthon cited the works of Erasmus as a highly influential guide for connecting theology back to original texts, which was important for the reform at Protestant universities.[34] Galileo Galilei, who taught at the Universities of Pisa and Padua, and Martin Luther, who taught at the University of Wittenberg (as did Melanchthon), also had humanist training. The task of the humanists was to slowly permeate the university; to increase the humanist presence in professorships and chairs, syllabi and textbooks so that published works would demonstrate the humanistic ideal of science and scholarship.[35]

Although the initial focus of the humanist scholars in the university was the discovery, exposition and insertion of ancient texts and languages into the university, and the ideas of those texts into society generally, their influence was ultimately quite progressive. The emergence of classical texts brought new ideas and lead to a more creative university climate (as the notable list of scholars above attests to). A focus on knowledge coming from self, from the human, has a direct implication for new forms of scholarship and instruction, and was the foundation for what is commonly known as the humanities. This disposition toward knowledge manifested in not simply the translation and propagation of ancient texts, but also their adaptation and expansion. For instance, Vesalius was imperative for advocating the use of Galen, but he also invigorated this text with experimentation, disagreements and further research.[36] The propagation of these texts, especially within the universities, was greatly aided by the emergence of the printing press and the beginning of the use of the vernacular, which allowed for the printing of relatively large texts at reasonable prices.[37]

Examining the influence of humanism on scholars in medicine, mathematics, astronomy and physics may suggest that humanism and universities were a strong impetus for the scientific revolution. Although the connection between humanism and the scientific discovery may very well have begun within the confines of the university, the connection has been commonly perceived as having been severed by the changing nature of science during the scientific revolution. Historians such as Richard Westfall have argued that the overt traditionalism of universities inhibited attempts to re-conceptualize nature and knowledge and caused an indelible tension between universities and scientists.[38] This resistance to changes in science may have been a significant factor in driving many scientists away from the university and toward private benefactors, usually in princely courts, and associations with newly forming scientific societies.[39]

Other historians find incongruity in the proposition that the very place where the vast number of the scholars that influenced the scientific revolution received their education should also be the place that inhibits their research and the advancement of science. In fact, more than 80% of the European scientists between 1450-1650 included in the Dictionary of Scientific Biography were university trained, of which approximately 45% held university posts.[40] It was the case that the academic foundations remaining from the Middle Ages were stable, and they did provide for an environment that fostered considerable growth and development. There was considerable reluctance on the part of universities to relinquish the symmetry and comprehensiveness provided by the Aristotelian system, which was effective as a coherent system for understanding and interpreting the world. However, university professors still utilized some autonomy, at least in the sciences, to choose epistemological foundations and methods. For instance, Melanchthon and his disciples at University of Wittenberg were instrumental for integrating Copernican mathematical constructs into astronomical debate and instruction.[41] Another example was the short-lived but fairly rapid adoption of Cartesian epistemology and methodology in European universities, and the debates surrounding that adoption, which led to more mechanistic approaches to scientific problems as well as demonstrated an openness to change. There are many examples which belie the commonly perceived intransigence of universities.[42] Although universities may have been slow to accept new sciences and methodologies as they emerged, when they did accept new ideas it helped to convey legitimacy and respectability, and supported the scientific changes through providing a stable environment for instruction and material resources.[43]

Regardless of the way the tension between universities, individual scientists, and the scientific revolution itself is perceived, there was a discernible impact on the way that university education was constructed. Aristotelian epistemology provided a coherent framework not simply for knowledge and knowledge construction, but also for the training of scholars within the higher education setting. The creation of new scientific constructs during the scientific revolution, and the epistemological challenges that were inherent within this creation, initiated the idea of both the autonomy of science and the hierarchy of the disciplines. Instead of entering higher education to become a “general scholar” immersed in becoming proficient in the entire curriculum, there emerged a type of scholar that put science first and viewed it as a vocation in itself. The divergence between those focused on science and those still entrenched in the idea of a general scholar exacerbated the epistemological tensions that were already beginning to emerge.[44]

The epistemological tensions between scientists and universities were also heightened by the economic realities of research during this time, as individual scientists, associations and universities were vying for limited resources. There was also competition from the formation of new colleges funded by private benefactors and designed to provide free education to the public, or established by local governments to provide a knowledge hungry populace with an alternative to traditional universities.[45] Even when universities supported new scientific endeavors, and the university provided foundational training and authority for the research and conclusions, they could not compete with the resources available through private benefactors.[46]

By the end of the early modern period, the structure and orientation of higher education had changed in ways that are eminently recognizable for the modern context. Aristotle was no longer a force providing the epistemological and methodological focus for universities and a more mechanistic orientation was emerging. The hierarchical place of theological knowledge had for the most part been displaced and the humanities had become a fixture, and a new openness was beginning to take hold in the construction and dissemination of knowledge that were to become imperative for the formation of the modern state.

Modern universities

Main articles: History of European research universities and List of modern universities in Europe (1801–1945)By the 18th century, universities published their own research journals and by the 19th century, the German and the French university models had arisen. The German, or Humboldtian model, was conceived by Wilhelm von Humboldt and based on Friedrich Schleiermacher’s liberal ideas pertaining to the importance of freedom, seminars, and laboratories in universities.[citation needed] The French university model involved strict discipline and control over every aspect of the university.

Until the 19th century, religion played a significant role in university curriculum; however, the role of religion in research universities decreased in the 19th century, and by the end of the 19th century, the German university model had spread around the world. Universities concentrated on science in the 19th and 20th centuries and became increasingly accessible to the masses. In Britain, the move from Industrial Revolution to modernity saw the arrival of new civic universities with an emphasis on science and engineering, a movement initiated in 1960 by Sir Keith Murray (chairman of the University Grants Committee) and Sir Samuel Curran, with the formation of the University of Strathclyde.[47] The British also established universities worldwide, and higher education became available to the masses not only in Europe. In a general sense, the basic structure and aims of universities have remained constant over the years.[48]

In 1963, the Robbins Report on universities in the United Kingdom concluded that such institutions should have four main "objectives essential to any properly balanced system: instruction in skills; the promotion of the general powers of the mind so as to produce not mere specialists but rather cultivated men and women; to maintain research in balance with teaching, since teaching should not be separated from the advancement of learning and the search for truth; and to transmit a common culture and common standards of citizenship."[49]

National universities

A national university is generally a university created or run by a national state but at the same time represent a state autonomic institutions which functions as a completely independent body inside of the same state. Some national universities are closely associated with national cultural or political aspirations, for instance the National University of Ireland in the early days of Irish independence collected a large amount of information on the Irish language and Irish culture. Reforms in Argentina were the result of the University Revolution of 1918 and its posterior reforms by incorporating values that sought for a more equal and laic higher education system.

Intergovernmental universities

Universities created by bilateral or multilateral treaty between states are intergovernmental. Such as Academy of European Law offering training in European law to lawyers, judges, barristers, solicitors, in-house counsel and academics. EUCLID (Pôle Universitaire Euclide, Euclid University) is chartered as a university and umbrella organization dedicated to sustainable development in signatory countries and United Nations University efforts to resolve the pressing global problems that are the concern of the United Nations, its Peoples and Member States.

Organization

Although each institution is organized differently, nearly all universities have a board of trustees; a president, chancellor, or rector; at least one vice president, vice-chancellor, or vice-rector; and deans of various divisions. Universities are generally divided into a number of academic departments, schools or faculties. Public university systems are ruled over by government-run higher education boards. They review financial requests and budget proposals and then allocate funds for each university in the system. They also approve new programs of instruction and cancel or make changes in existing programs. In addition, they plan for the further coordinated growth and development of the various institutions of higher education in the state or country. However, many public universities in the world have a considerable degree of financial, research and pedagogical autonomy. Private universities are privately funded and generally have a broader independence from state policies. However, they may have less independence from business corporations depending on the source of their finances.

Universities around the world

The funding and organization of universities varies widely between different countries around the world. In some countries universities are predominantly funded by the state, while in others funding may come from donors or from fees which students attending the university must pay. In some countries the vast majority of students attend university in their local town, while in other countries universities attract students from all over the world, and may provide university accommodation for their students.[50]

Classification

The definition of a university varies widely even within some countries. For example, there is no nationally standardized definition of the term in the United States although the term has traditionally been used to designate research institutions and was once reserved for research doctorate-granting institutions.[51] Some states, such as Massachusetts, will only grant a school "university status" if it grants at least two doctoral degrees.[52] In the United Kingdom, the Privy Council is responsible for approving the use of the word "university" in the title of an institution, under the terms of the Further and Higher Education Act 1992.[53] In India, a new tag deemed universities was created a few years ago, by the cabinet minister Arjun Singh during his tenure as the Minister for Human Resource Development. Through this provision many universities sprung up in India, which are commercial in nature and have been established just to exploit the demand of higher education.[54]

Colloquial usage

Colloquially, the term university may be used to describe a phase in one's life: "When I was at university..." (in the United States and Ireland, college is often used instead: "When I was in college..."; see the college article for further discussion). In Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands and the German-speaking countries university is often contracted to uni.[citation needed] In New Zealand and in South Africa it is sometimes called "varsity" (although this has become uncommon in New Zealand in recent years), which was also common usage in the UK in the 19th century.[citation needed]

Cost

Main article: Tuition paymentsMany students look to get 'student grants' to cover the cost of university. The cost may rise for students, as a result of decreased funding given to universities.

Religious and political control of universities

In some countries, in some political systems, universities are controlled by political or religious authorities who forbid certain fields of study or impose certain other fields. Sometimes national or racial limitations exist in the students that can be admitted, the faculty and staff that can be employed, and the research that can be conducted (e.g. in Nazi Germany).

See also

- Alternative university

- Catholic University

- College and university rankings

- Corporate university

- International university

- G. I. American Universities

- Land-grant university

- List of academic disciplines

- Lists of universities and colleges

- Nation (university)

- Pontifical university

- School and university in literature

- University student retention

- University system

- Urban university

Notes

- ^ Google eBook of '''''Encyclopedia Britannica'''''. Books.google.com. 2006-09-22. http://books.google.com/?id=5vgGE8_CGOEC&pg=PA748&lpg=PA748&dq=community+of+teachers+and+scholars+universitas+magistrorum+et+scholarium. Retrieved 2010-05-28.

- ^ Marcia L. Colish, Medieval Foundations of the Western Intellectual Tradition, 400-1400, (New Haven: Yale Univ. Pr., 1997), p. 267.

- ^ Malagola, C. (1888), Statuti delle Università e dei Collegi dello Studio Bolognese. Bologna: Zanichelli.

- ^ a b Rüegg, W. (2003), Mythologies and Historiogaphy of the Beginnings, pp 4-34 in H. De Ridder-Symoens, editor, A History of the University in Europe; Vol 1, Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Watson, P. (2005), Ideas. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, page 373

- ^ "Magna Charta delle Università Europee". .unibo.it. http://www2.unibo.it/avl/charta/charta.htm. Retrieved 2010-05-28.

- ^ Riché, Pierre (1978): "Education and Culture in the Barbarian West: From the Sixth through the Eighth Century", Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, ISBN 0-87249-376-8, pp. 126-7, 282-98

- ^ Johnson, P. (2000). The Renaissance : a short history. Modern Library chronicles (Modern Library ed.). New York: Modern Library, p. 9.

- ^ "The Origin Of Universities". Cwrl.utexas.edu. http://www.cwrl.utexas.edu/~bump/OriginUniversities.html. Retrieved 2010-05-28.

- ^ and University of Coimbra founded in Lisbon and was based there in 1290-1308, 1338-54, and 1377-1537.Medieval Universities And the Origin of the College

- ^ Makdisi, G. (1981), Rise of Colleges: Institutions of Learning in Islam and the West. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- ^ Daun, H. and Arjmand, R. (2005), Islamic Education, pp 377-388 in J. Zajda, editor, International Handbook of Globalisation, Education and Policy Research. Netherlands: Springer.

- ^ Huff, T. (2003), The Rise of Early Modern Science. Cambridge University Press, p. 122

- ^ Kerr, C. (2001), The Uses of the University. P Harvard University Press.p.16 and 145

- ^ Rüegg, W. (2003), Mythologies and Historiogaphy of the Beginnings, pp 4-34 in H. De Ridder-Symoens, editor, A History of the University in Europe; Vol 1, Cambridge University Press.p. 12

- ^ Grendler, P. F. (2004). "The universities of the Renaissance and Reformation". Renaissance Quarterly, 57, pp. 2.

- ^ Rubenstein, R. E. (2003). Aristotle's children: how Christians, Muslims, and Jews rediscovered ancient wisdom and illuminated the dark ages (1st ed.). Orlando, Fla: Harcourt, pp. 16-17.

- ^ Dales, R. C. (1990). Medieval discussions of the eternity of the world (Vol. 18). Brill Archive, p. 144.

- ^ Grendler, P. F. (2004). "The universities of the Renaissance and Reformation". Renaissance Quarterly, 57, pp. 2-8.

- ^ Scott, J. C. (2006). The mission of the university: Medieval to Postmodern transformations. Journal of Higher Education, 77(1), p. 6.

- ^ Rüegg, Walter: "Foreword. The University as a European Institution", in: A History of the University in Europe. Vol. 1: Universities in the Middle Ages, Cambridge University Press, 1992, ISBN 0-521-36105-2, pp. XIX–XX

- ^ Makdisi, George (April–June 1989). "Scholasticism and Humanism in Classical Islam and the Christian West". Journal of the American Oriental Society (Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 109, No. 2) 109 (2): 175–182 [175–77]. doi:10.2307/604423. JSTOR 604423; Makdisi, John A. (June 1999). "The Islamic Origins of the Common Law". North Carolina Law Review 77 (5): 1635–1739; Goddard, Hugh (2000). A History of Christian-Muslim Relations. Edinburgh University Press. p. 99. ISBN 074861009X

- ^ George Makdisi: "Madrasa and University in the Middle Ages", Studia Islamica, No. 32 (1970), pp. 255-264 (264):

Toby Huff, Rise of Early Modern Science: Islam, China and the West, 2nd ed., Cambridge 2003, ISBN 0521529948, p. 133-139, 149-159, 179-189; Encyclopaedia of Islam has an entry on the "madrasa" but lacks notably one for a medieval Muslim "university" (Pedersen, J.; Rahman, Munibur; Hillenbrand, R. "Madrasa." Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Edited by: P. Bearman , Th. Bianquis , C.E. Bosworth , E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs. Brill, 2010, retrieved 21 March 2010)Thus the university, as a form of social organization, was peculiar to medieval Europe. Later, it was exported to all parts of the world, including the Muslim East; and it has remained with us down to the present day. But back in the middle ages, outside of Europe, there was nothing anything quite like it anywhere. - ^ Norman Daniel: Review of "The Rise of Colleges. Institutions of Learning in Islam and the West by George Makdisi", Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 104, No. 3 (Jul. - September, 1984), pp. 586-588 (587)

- ^ Grendler, P. F. (2004). The universities of the Renaissance and Reformation. Renaissance Quarterly, 57, pp. 1-3.

- ^ Frijhoff, W. (1996). Patterns. In H. D. Ridder-Symoens (Ed.), Universities in early modern Europe, 1500-1800, A history of the university in Europe. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press, p. 75.

- ^ Frijhoff, W. (1996). Patterns. In H. D. Ridder-Symoens (Ed.), Universities in early modern Europe, 1500-1800, A history of the university in Europe. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press, p. 47.

- ^ Grendler, P. F. (2004). The universities of the Renaissance and Reformation. Renaissance Quarterly, 57, p. 23.

- ^ Scott, J. C. (2006). The mission of the university: Medieval to Postmodern transformations. Journal of Higher Education, 77(1), pp. 10-13.

- ^ Frijhoff, W. (1996). Patterns. In H. D. Ridder-Symoens (Ed.), Universities in early modern Europe, 1500-1800, A history of the university in Europe. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press, p. 65.

- ^ Ruegg, W. (1992). Epilogue: the rise of humanism. In H. D. Ridder-Symoens (Ed.), Universities in the Middle Ages, A history of the university in Europe. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Grendler, P. F. (2002). The universities of the Italian renaissance. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, p. 223.

- ^ Grendler, P. F. (2002). The universities of the Italian renaissance. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, p. 197.

- ^ Ruegg, W. (1996). Themes. In H. D. Ridder-Symoens (Ed.), Universities in Early Modern Europe, 1500-1800, A history of the university in Europe. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press, pp. 33-39.

- ^ Grendler, P. F. (2004). The universities of the Renaissance and Reformation. Renaissance Quarterly, 57, pp. 12-13.

- ^ Bylebyl, J. J. (2009). Disputation and description in the renaissance pulse controversy. In A. Wear, R. K. French, & I. M. Lonie (Eds.), The medical renaissance of the sixteenth century (1st ed., pp. 223-245). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Füssel, S. (2005). Gutenberg and the Impact of Printing (English ed.). Aldershot, Hampshire: Ashgate Pub., p. 145.

- ^ Westfall, R. S. (1977). The construction of modern science: mechanisms and mechanics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 105.

- ^ Ornstein, M. (1928). The role of scientific societies in the seventeenth century. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- ^ Gascoigne, J. (1990). A reappraisal of the role of the universities in the Scientific Revolution. In D. C. Lindberg & R. S. Westman (Eds.), Reappraisals of the Scientific Revolution, pp. 208-209.

- ^ Westman, R. S. (1975). The Melanchthon circle:, rheticus, and the Wittenberg interpretation of the Copernicantheory. Isis, 66(2), 164-193.

- ^ Gascoigne, J. (1990). A reappraisal of the role of the universities in the Scientific Revolution. In D. C. Lindberg & R. S. Westman (Eds.), Reappraisals of the Scientific Revolution, pp. 210-229.

- ^ Gascoigne, J. (1990). A reappraisal of the role of the universities in the Scientific Revolution. In D. C. Lindberg & R. S. Westman (Eds.), Reappraisals of the Scientific Revolution, pp. 245-248.

- ^ Feingold, M. (1991). Tradition vs novelty: universities and scientific societies in the early modern period. In P. Barker & R. Ariew (Eds.), Revolution and continuity: essays in the history and philosophy of early modern science, Studies in philosophy and the history of philosophy. Washington, D.C: Catholic University of America Press, pp. 53-54.

- ^ Feingold, M. (1991). Tradition vs novelty: universities and scientific societies in the early modern period. In P. Barker & R. Ariew (Eds.), Revolution and continuity: essays in the history and philosophy of early modern science, Studies in philosophy and the history of philosophy. Washington, D.C: Catholic University of America Press, pp. 46-50.

- ^ see, for instance, Baldwin, M. (1995). The snakestone experiments: an early modern medical debate. Isis, 86(3), 394-418.

- ^ "Oxford Dictionary of National Biography". Oxforddnb.com. http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/69524. Retrieved 2010-05-28.

- ^ "Modern University Management". http://modernuniversitymanagement.com.

- ^ Anderson, Robert (March 2010). "The 'Idea of a University' today" (in English). History & Policy. United Kingdom: History & Policy. http://www.historyandpolicy.org/papers/policy-paper-98.html. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- ^ "Basic Classification Technical Details". Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. http://www.carnegiefoundation.org/classifications/index.asp?key=798. Retrieved 2007-03-20.

- ^ US Department of State: Types of Graduate schools

- ^ "Massachusetts Board of Education: Degree-granting regulations for independent institutions of higher education" (PDF). http://www.mass.edu/forinstitutions/academic/documents/610CMR.pdf. Retrieved 2010-05-28.

- ^ "Higher Education". Privy Council Office. Archived from the original on 2009-02-23. http://web.archive.org/web/20090223084511/http://www.privy-council.org.uk/output/Page27.asp. Retrieved 2007-12-06.

- ^ — Peter Drucker. "‘Deemed’ status distributed freely during Arjun Singh’s tenure - LearnHub News". Learnhub.com. http://learnhub.com/news/1254-. Retrieved 2010-07-29.

References

- Aronowitz, Stanley (2000). The Knowledge Factory: Dismantling the Corporate University and Creating True Higher Learning. Boston: Beacon Press. ISBN 978-0807031223.

- Barrow, Clyde W. (1990). Universities and the Capitalist State: Corporate Liberalism and the Reconstruction of American Higher Education, 1894-1928. Madison, Wis: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0299124007.

- Diamond, Sigmund (1992). Compromised Campus: The Collaboration of Universities with the Intelligence Community, 1945-1955. New York, NY: Oxford Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0195053821.

- Pedersen, Olaf (1997). The First Universities: Studium Generale and the Origins of University Education in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0521594318.

- Ridder-Symoens, Hilde de, ed (1992). A History of the University in Europe. Volume 1: Universities in the Middle Ages. Rüegg, Walter (general ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-36105-2.

- Ridder-Symoens, Hilde de, ed (1996). A History of the University in Europe. Volume 2: Universities in Early Modern Europe (1500-1800). Rüegg, Walter (general ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-36106-0.

- Rüegg, Walter, ed (2004). A History of the University in Europe. Volume 3: Universities in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries (1800-1945). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-36107-9.

External links

Schools by educational stage Academy · College · Community college · Graduate school · Institute of technology · Junior college · University · Upper division college · Vocational universityby funding / eligibility Academy (England) · Charter school · Comprehensive school · For-profit education · Free education · Free school (England) · Independent school · Independent school (United Kingdom) · Preparatory school (United Kingdom) · Private school · Selective school · State or public schoolby style of education Adult education · Alternative school · Boarding school · Day school · Folk high school · Free skool · Homeschool · International school · K-12 · Madrasah · Magnet school · Montessori school · Parochial school · Virtual schoolby scope Topics in education Categories:- Educational stages

- Higher education

- Types of university or college

- Universities and colleges

- Youth

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.

Synonyms:

Look at other dictionaries:

University — U ni*ver si*ty, n.; pl. {Universities}. [OE. universite, L. universitas all together, the whole, the universe, a number of persons associated into one body, a society, corporation, fr. universus all together, universal: cf. F. universit[ e]. See… … The Collaborative International Dictionary of English

University — University, FL U.S. Census Designated Place in Florida Population (2000): 30736 Housing Units (2000): 15494 Land area (2000): 3.870401 sq. miles (10.024292 sq. km) Water area (2000): 0.011633 sq. miles (0.030129 sq. km) Total area (2000):… … StarDict's U.S. Gazetteer Places

University, FL — U.S. Census Designated Place in Florida Population (2000): 30736 Housing Units (2000): 15494 Land area (2000): 3.870401 sq. miles (10.024292 sq. km) Water area (2000): 0.011633 sq. miles (0.030129 sq. km) Total area (2000): 3.882034 sq. miles (10 … StarDict's U.S. Gazetteer Places

university — [yo͞o΄nə vʉr′sə tē] n. pl. universities [ME universite < MFr université < ML universitas < L, the whole, universe, society, guild < universus: see UNIVERSE] 1. an educational institution of the highest level, typically, in the U.S.,… … English World dictionary

university — c.1300, institution of higher learning, also body of persons constituting a university, from Anglo Fr. université, O.Fr. universitei (13c.), from M.L. universitatem (nom. universitas), in L.L. corporation, society, from L., the whole, aggregate,… … Etymology dictionary

university — index institute Burton s Legal Thesaurus. William C. Burton. 2006 … Law dictionary

university — ► NOUN (pl. universities) ▪ a high level educational institution in which students study for degrees and academic research is done. ORIGIN Latin universitas the whole , later guild , from universus (see UNIVERSE(Cf. ↑universe)) … English terms dictionary

university — universitarian /yooh neuh verr si tair ee euhn/, n., adj. /yooh neuh verr si tee/, n., pl. universities. an institution of learning of the highest level, having a college of liberal arts and a program of graduate studies together with several… … Universalium

university — n. 1) to establish, found a university 2) to go to a university/to go to university (BE) (she goes to a good university) 3) a free, open; people s university 4) an Ivy League (US); redbrick (GB); state (US) university 5) at; in a university (to… … Combinatory dictionary

university — noun ADJECTIVE ▪ elite, leading, major, prestigious, top ▪ ancient (esp. BrE) ▪ modern, new, red bri … Collocations dictionary