- Crowding out (economics)

-

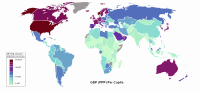

Economics  Economies by region

Economies by regionGeneral categories Microeconomics · Macroeconomics

History of economic thought

Methodology · Mainstream & heterodoxTechnical methods Mathematical economics

Game theory · Optimization

Computational · Econometrics

Experimental · National accountingFields and subfields Behavioral · Cultural · Evolutionary

Growth · Development · History

International · Economic systems

Monetary and Financial economics

Public and Welfare economics

Health · Education · Welfare

Population · Labour · Managerial

Business · Information

Industrial organization · Law

Agricultural · Natural resource

Environmental · Ecological

Urban · Rural · Regional · GeographyLists Business and Economics Portal In economics, crowding out is a reduction in private investment that occurs because of an increase in government borrowing. If an increase in government spending and/or a decrease in tax revenues leads to a deficit that is financed by increased borrowing, then the borrowing can increase interest rates, leading to a reduction in private investment. There is some controversy in modern macroeconomics on the subject, as different schools of economic thought differ on how households and financial markets would react to more government borrowing under various circumstances.

Usually when economists use the term "crowding out" they are referring to the government spending using up financial and other resources that would otherwise be used by private enterprise. However, some commentators and other economists use "crowding out" to refer to government providing a service or good that would otherwise be a business opportunity for private industry.

The macroeconomic theory behind crowding out provides some useful intuition for those trying to gain a tight grasp of the concept. What happens is that an increase in the demand for loanable funds by the government (e.g. due to a deficit) shifts the loanable funds demand curve rightwards and upwards, increasing the real interest rate. A higher real interest rate increases the opportunity cost of borrowing money, decreasing the amount of interest-sensitive expenditures such as investment and consumption. Hence, the government has "crowded out" investment.

Contents

Crowding out resources

If increased borrowing leads to higher interest rates by creating a greater demand for money and loanable funds and hence a higher "price" (ceteris paribus), the private sector, which is sensitive to interest rates, will likely reduce investment due to a lower rate of return. This is the investment that is crowded out. The weakening of fixed investment and other interest-sensitive expenditure counteracts to varying extents the expansionary effect of government deficits. More importantly, a fall in fixed investment by business can hurt long-term economic growth of the supply side, i.e., the growth of potential output.

Thus, the situation in which borrowing may lead to crowding out is that companies would like to expand productive capacity, but, because of high interest rates, cannot borrow funds with which to do so. According to American economist Jared Bernstein, writing in 2011, this scenario is "not a plausible story with excess capacity, the Fed funds [interest] rate at zero, and companies sitting on cash that they could invest with if they saw good reasons to do so."[1] Another American economist, Paul Krugman, pointed out that, after the beginning of the recession in 2008, the federal government's borrowing increased by hundreds of billions of dollars, leading to warnings about crowding out, but instead interest rates had actually fallen.[2] When aggregate demand is low, government spending tends to expand the market for private-sector products through the fiscal multiplier and thus stimulates – or "crowds in" – fixed investment (via the "accelerator effect"). This accelerator effect is most important when business suffers from unused industrial capacity, i.e., during a serious recession or a depression.

Crowding out can, in principle, be avoided if the deficit is financed by simply printing money, but this carries concerns of accelerating inflation.

Chartalist and Post-Keynesian economists critique crowding out because government bonds sales have the actual effect of lowering short-term interest rates, not raising them, since the rate for short-term debt is always set by central banks. Additionally, private credit is not constrained by any "amount of funds" or "money supply" or similar concept. Rather, banks lend to any credit-worthy customer, constrained by their capitalization level and risk regulations. The resulting loan creates a deposit simultaneously, increasing the amount of endogenous money at that time.

Crowding out is most serious when an economy is already at potential output or full employment. Then the government's expansionary fiscal policy encourages increased prices, which lead to an increased demand for money. This in turn leads to higher interest rates (ceteris paribus) and crowds out interest-sensitive spending. At potential output, businesses are in no need of markets, so that there is no room for an accelerator effect. More directly, if the economy stays at full employment gross domestic product, any increase in government purchases shifts resources away from the private sector. This phenomenon is sometimes called "real" crowding out.

The negative effects on long-term economic growth that occur when private fixed investment are crowded out can be moderated if the government uses its deficit to finance productive investment in education, basic research, and the like. The situation is made worse, of course, if the government wastes borrowed money.

Crowding out of another sort (often referred to as international crowding out) may occur due to the prevalence of floating exchange rates, as demonstrated by the Mundell-Fleming model. Government borrowing leads to higher interest rates, which attract inflows of money on the capital account from foreign financial markets into the domestic currency (i.e., into assets denominated in that currency). Under floating exchange rates, that leads to appreciation of the exchange rate and thus the "crowding out" of domestic exports (which become more expensive to those using foreign currency). This counteracts the demand-promoting effects of government deficits but has no obvious negative effect on long-term economic growth.

Crowding out demand

In terms of health economics, "crowding-out" refers to the phenomenon whereby new or expanded programs meant to cover the uninsured have the effect of prompting those already enrolled in private insurance to switch to the new program. This effect was seen, for example, in expansions to Medicaid and the State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) in the late 1990s.[citation needed]

Therefore, high takeup rates for new or expanded programs do not merely represent the previously uninsured, but also represent those who may have been forced to shift their health insurance from the private to the public sector. As a result of these shifts, it can be projected that healthcare improvements as a result of policy change may not be as robust. In the context of the CHIP debate, this assumption was challenged by projections produced by the Congressional Budget Office, which "scored" all versions of the CHIP reauthorization and included in those scores the best assumptions available regarding the impacts of increased funding for these programs. CBO assumed that many already eligible children would become enrolled as a result of the new funding and policies in CHIP reauthorization, but that some would be eligible for private insurance.[3] The vast majority, even in states with enrollments of those above twice the poverty line (around $40,000 for a family of four), did not have access to age-appropriate health insurance for their children. New Jersey, supposedly the model for profligacy in SCHIP with eligibility that stretched to 350% of the federal poverty level, testified that it could identify 14% crowd-out in its CHIP program.[4]

In the context of CHIP and Medicaid, many children are eligible but not enrolled. Thus, in comparison to Medicare, which allows for near "auto-enrollment" for those over 64, children's caregivers may be required to fill out 17-page forms, produce multiple consecutive pay stubs, re-apply at more than yearly intervals and even conduct face-to-face interviews to prove the eligibility of the child.[5] These anti-crowd-out procedures can fracture care for children, sever the connection to their medical home and lead to worse health outcomes.[6]

Some strategies to combat the effect of crowding out are to instate waiting periods, to limit eligibility to the uninsured, to subsidize employer-based insurance, or to apply a premium to families at higher levels of income eligibility. At this point, every CHIP program requires premiums at higher income eligibility and many undertake all of these strategies to encourage enrollment of those without insurance. However, crowding out may not be entirely negative, and may reflect the fact that the insurance that many low-wage employees receive is inadequate, and the state program would present an improvement to healthcare access.

History

The idea of the crowding out effect, though not the term itself, has been discussed since at least the 18th century. In his pamphlet Great-Britain’s True System (1757), English economic popularizer Malachy Postlethwayt wrote (p. 69):[7]

The national Debts first drew out of private Hands, most of the Money which should, and otherwise would have been lent out to our skilful and industrious Merchants and Tradesmen: this made it difficult for such to borrow any Money upon personal Security, and this Difficulty soon made it unsafe to lend any upon such Security; which of Course destroyed all private Credit; thereby greatly injured our Commerce in general . . .

See also

- Motivation crowding theory

- Treasury View

Notes

- ^ Bernstein, Jared (May 25, 2011). "Cut and Grow? I Say No.". http://jaredbernsteinblog.com/cut-and-grow-i-say-no/. Retrieved 2011-05-28.

- ^ Krugman, Paul (August 20, 2011), "Fancy Theorists of the World Unite", The New York Times, http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/08/20/fancy-theorists-of-the-world-unite/, retrieved 2011-08-22

- ^ http://www.cbo.gov/doc.cfm?index=9963

- ^ http://energycommerce.house.gov/cmte_mtgs/110-he-hrg.012908.Kohler-testimony.pdf

- ^ http://www.ajph.org/cgi/content/full/95/2/292

- ^ http://content.healthaffairs.org/cgi/content/full/23/3/233?maxtoshow=&HITS=10&hits=10&RESULTFORMAT.

- ^ Michael Hudson, “How economic theory came to ignore the role of debt”, real-world economics review, issue no. 57, 6 September 2011, pp. 2–24, comments, cited at bottom of page 5

References

- Olivier J. Blanchard, 2008. "crowding out," The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd Ed., Abstract.

- Roger W. Spencer & William P. Yohe, 1970. "The 'Crowding Out' of Private Expenditures by Fiscal Policy Actions", Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, October, pp. 12-24 (press+).

- Susan M. Evens, Crowding Out: Theories and Evidence (Adelaide 1977).

Categories:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.