- Evolutionary economics

-

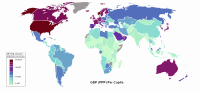

Economics  Economies by region

Economies by regionGeneral categories Microeconomics · Macroeconomics

History of economic thought

Methodology · Mainstream & heterodoxTechnical methods Mathematical economics

Game theory · Optimization

Computational · Econometrics

Experimental · National accountingFields and subfields Behavioral · Cultural · Evolutionary

Growth · Development · History

International · Economic systems

Monetary and Financial economics

Public and Welfare economics

Health · Education · Welfare

Population · Labour · Managerial

Business · Information

Industrial organization · Law

Agricultural · Natural resource

Environmental · Ecological

Urban · Rural · Regional · GeographyLists Business and Economics Portal Evolutionary economics is part of mainstream economics as well as heterodox school of economic thought that is inspired by evolutionary biology. Much like mainstream economics, it stresses complex interdependencies, competition, growth, structural change, and resource constraints but differs in the approaches which are used to analyze these phenomena.[1]

Evolutionary economics deals with the study of processes that transform economy for firms, institutions, industries, employment, production, trade and growth within, through the actions of diverse agents from experience and interactions, using evolutionary methodology.

Evolutionary economics analyses the unleashing of a process of technological and institutional innovation by generating and testing a diversity of ideas which discover and accumulate more survival value for the costs incurred than competing alternatives. The evidence suggests that it could be adaptive efficiency that defines economic efficiency.

Mainstream economic reasoning begins with the postulates of scarcity and rational agents (that is, agents modeled as maximizing their individual welfare), with the "rational choice" for any agent being a straightforward exercise in mathematical optimization. There has been renewed interest in treating economic systems as evolutionary systems in the developing field of Complexity economics.

Evolutionary economics does not take the characteristics of either the objects of choice or of the decision-maker as fixed. Rather its focus is on the non-equilibrium processes that transform the economy from within and their implications. The processes in turn emerge from actions of diverse agents with bounded rationality who may learn from experience and interactions and whose differences contribute to the change. The subject draws more recently on evolutionary game theory[2] and on the evolutionary methodology of Charles Darwin and the non-equilibrium economics principle of circular and cumulative causation. It is naturalistic in purging earlier notions of economic change as teleological or necessarily improving the human condition.[3]

Contents

Predecessors

In the mid-19th century was presented[by whom?] a schema of stages of historical development, by introducing the notion that "human nature" was not constant and was not determinative of the nature of the social system; on the contrary, he made it a principle that human behavior was a function of the social and economic system in which it occurred.

Karl Marx based his theory of economic development on the premise of evolving economic systems; specifically, over the course of history superior economic systems would replace inferior ones. Inferior systems were beset by internal contradictions and inefficiencies that make them impossible to survive over the long term. In Marx's scheme, feudalism was replaced by capitalism, which would eventually be superseded by communism.[4]

At approximately the same time, Charles Darwin developed a general framework for comprehending any process whereby small, random variations could accumulate and predominate over time into large-scale changes that resulted in the emergence of wholly novel forms ("speciation").

This was followed shortly after by the work of the American pragmatic philosophers (James, Peirce, Dewey) and the founding of two new disciplines, psychology and anthropology, both of which were oriented toward cataloging and developing explanatory frameworks for the variety of behavior patterns (both individual and collective) that were becoming increasingly obvious to all systematic observers. The state of the world converged with the state of the evidence to make almost inevitable the development of a more "modern" framework for the analysis of substantive economic issues.

Thorstein Veblen (1898) coined the term "evolutionary economics" in English. He began his career in the midst of this period of intellectual ferment, and as a young scholar came into direct contact with some of the leading figures of the various movements that were to shape the style and substance of social sciences into the next century and beyond. Veblen saw the need for taking account of cultural variation in his approach; no universal "human nature" could possibly be invoked to explain the variety of norms and behaviors that the new science of anthropology showed to be the rule, rather than the exception. He emphasised the conflict between "industrial" and "pecuniary" values and in the hands of later writers this was interpreted as the "ceremonial / instrumental dichotomy" (Hodgson 2004); Veblen saw that every culture is materially-based and dependent on tools and skills to support the "life process", while at the same time, every culture appeared to have a stratified structure of status ("invidious distinctions") that ran entirely contrary to the imperatives of the "instrumental" (read: "technological") aspects of group life. The "ceremonial" was related to the past, and conformed to and supported the tribal legends; "instrumental" was oriented toward the technological imperative to judge value by the ability to control future consequences. The "Veblenian dichotomy" was a specialized variant of the "instrumental theory of value" due to John Dewey, with whom Veblen was to make contact briefly at the University of Chicago.

Arguably the most important works by Veblen include, but are not restricted to, his most famous works (Theory of the Leisure Class; Theory of Business Enterprise), but his monograph Imperial Germany and the Industrial Revolution and the 1898 essay entitled Why is Economics not an Evolutionary Science have both been influential in shaping the research agenda for following generations of social scientists. TOLC and TOBE together constitute an alternative construction on the neoclassical marginalist theories of consumption and production, respectively. Both are founded on his dichotomy, which is at its core a valuational principle. The ceremonial patterns of activity are not bound to any past, but to one that generated a specific set of advantages and prejudices that underlie the current institutions. "Instrumental" judgments create benefits according to a new criterion, and therefore are inherently subversive. This line of analysis was more fully and explicitly developed by Clarence E. Ayres of the University of Texas at Austin from the 1920s.

Kenneth Boulding was one of the advocates of the evolutionary methods in social science, as is evident from Kenneth Boulding's Evolutionary Perspective. Kenneth Arrow, Ronald Coase and Douglass North are some of the Bank of Sweden Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel winners who are known for their sympathy to the field.

More narrowly the works Jack Downie[5] and Edith Penrose[6] offer many insights for those thinking about evolution at the level of the firm in an industry.

Schumpeter's "Entwicklung"

Joseph Schumpeter, who lived in the first half of 20th century, was the author of the book The Theory of Economic Development (1911, transl. 1934). It is important to note that for the word development he used in his native language, the German word "Entwicklung", which can be translated as development or evolution. The translators of the day used the word "development" from the French "développement", as opposed to "evolution" as this was used by Darwin. (Schumpeter, in his later writings in English as a professor at Harvard, used the word "evolution".) The current term in common use is economic development.[citation needed]

In Schumpeter's book he proposed an idea radical for its time: the evolutionary perspective. He based his theory on the assumption of usual macroeconomic equilibrium, which is something like "the normal mode of economic affairs". This equilibrium is being perpetually destroyed by entrepreneurs who try to introduce innovations. A successful introduction of an innovation disturbs the normal flow of economic life, because it forces some of the already existing technologies and means of production to lose their positions within the economy.[citation needed]

Present state of discussion

One of the major contributions to the emerging field of evolutionary economics has been the publication of 'An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change' by Richard Nelson and Sidney Winter. These authors have focused mostly on the issue of changes in technology and routines, suggesting a framework for their analysis. If the change occurs constantly in the economy, then some kind of evolutionary process must be in act, and there has been a proposal that this process is Darwinian in nature. Then, mechanisms that provide selection, generate variation and establish self-replication, must be identified.

Milton Friedman proposed that markets act as major selection vehicles. As firms compete, unsuccessful rivals fail to capture an appropriate market share, go bankrupt and have to exit[7]. The variety of competing firms is both in their products and practices, that are matched against markets. Both products and practices are determined by routines that firms use: standardized patterns of actions implemented constantly. By imitating these routines, firms propagate them and thus establish inheritance of successful practices.[8][9]

A key contribution to the current discussion is Esben Andersen's book Schumpeter's Evolutionary Economics (2009).

See also

- Behavioral economics

- Complexity economics

- Creative destruction

- Cultural economics

- Darwinism

- EAEPE

- Ecological model of competition

- Economics

- Evolutionary socialism

- Hypergamy

- Institutional economics

- Natural selection

- Population dynamics

- Social Darwinism

- Innovation system

- Non-equilibrium economics

- Universal Darwinism

Notes

- ^ Geoffrey M. Hodgson (1993) Economics and Evolution: Bringing Life Back Into Economics, Cambridge and University of Michigan Press. Description and chapter-link preview.

- ^ Daniel Friedman (1998). "On Economic Applications of Evolutionary Game Theory," Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 8(1), pp. 15-43.

- ^ Ulrich Witt (2008). "evolutionary economics." The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd Edition, v. 3, pp. 67-68 Abstract.

- ^ Gregory and Stuart. (2005) Comparing Economic Systems in the Twenty-First Century, Seventh Edition, South-Western College Publishing, ISBN 0-618-26181-8

- ^ Jack Downie (1958) The Competitive Process

- ^ E. Penrose (1959) The Theory of the Growth of the Firm

- ^ Mazzucato, M. (2000), Firm Size, Innovation and Market Structure: The Evolution of Market Concentration and Instability, Edward Elgar, Northampton, MA, ISBN 1-84064-346-3, 138 pages.

- ^ Friedman, Milton (1953). Essays in Positive Economics, University of Chicago Press. Chapter preview links.

- ^ Page 251: Jon Elster, Explaining Technical Change : a Case Study in the Philosophy of Science, Second ed.

References

- Aldrich, Howard E., Geoffrey M. Hodgson, David L. Hull, Thorbjørn Knudsen, Joel Mokyr and Viktor J. Vanberg (2008) ‘In Defence of Generalized Darwinism’, Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 18(5), October, pp. 577–96.

- Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (2004) The Evolution of Institutional Economics: Agency, Structure and Darwinism in American Institutionalism (London and New York: Routledge).

- Richard R. Nelson and Sidney G. Winter. (1982). An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change. Harvard University Press.

- Sidney G. Winter (1987). "natural selection and evolution," The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, v. 3, pp. 614–17.

- Veblen, Thorstein B. (1898) ‘Why Is Economics Not an Evolutionary Science?’, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 12(3), July, pp. 373–97.

Journals

- Journal of Evolutionary Economics. Description and article-preview links.

External links

- Evolutionary economics at the Open Directory Project

- "Evolutionary Economics et al." by Prof. Esben S. Andersen - Aalborg University, Denmark

- Evolutionary Economics by J.P. Birchall

Categories:- Heterodox economics

- Dichotomies

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.