- Complexity economics

-

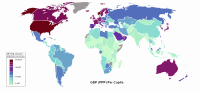

Economics  Economies by region

Economies by regionGeneral categories Microeconomics · Macroeconomics

History of economic thought

Methodology · Mainstream & heterodoxTechnical methods Mathematical economics

Game theory · Optimization

Computational · Econometrics

Experimental · National accountingFields and subfields Behavioral · Cultural · Evolutionary

Growth · Development · History

International · Economic systems

Monetary and Financial economics

Public and Welfare economics

Health · Education · Welfare

Population · Labour · Managerial

Business · Information

Industrial organization · Law

Agricultural · Natural resource

Environmental · Ecological

Urban · Rural · Regional · GeographyLists Business and Economics Portal Complexity economics is the application of complexity science to the problems of economics. It studies computer simulations to gain insight into economic dynamics, and avoids the assumption that the economy is a system in equilibrium.[1]

Contents

Models

The "nearly archetypal example" is an artificial stock market model created by the Santa Fe Institute in 1989.[2] The model shows two different outcomes, one where "agents do not search much for predictors and there is convergence on a homogeneous rational expectations outcome" and another where "all kinds of technical trading strategies appearing and remaining and periods of bubbles and crashes occurring".[2]

Another area has studied the prisoner's dilemma, such as in a network where agents play amongst their nearest neighbors or a network where the agents can make mistakes from time to time and "evolve strategies".[2] In these models, the results show a system which displays "a pattern of constantly changing distributions of the strategies".[2]

Features

Brian Arthur, Steven N. Durlauf, and David A. Lane describe several features of complex systems that deserve greater attention in economics.[3]

- Dispersed interaction—The economy has interaction between many dispersed, heterogeneous, agents. The action of any given agent depends upon the anticipated actions of other agents and on the aggregate state of the economy.

- No global controller—Controls are provided by mechanisms of competition and coordination between agents. Economic actions are mediated by legal institutions, assigned roles, and shifting associations. No global entity controls interactions. Traditionally, a fictitious auctioneer has appeared in some mathematical analyses of general equilibrium models, although nobody claimed any descriptive accuracy for such models. Traditionally, many mainstream models have imposed constraints, such as requiring that budgets be balanced, and such constraints are avoided in complexity economics.

- Cross-cutting hierarchical organization—The economy has many levels of organization and interaction. Units at any given level behaviors, actions, strategies, products typically serve as "building blocks" for constructing units at the next higher level. The overall organization is more than hierarchical, with many sorts of tangling interactions (associations, channels of communication) across levels.

- Ongoing adaptation—Behaviors, actions, strategies, and products are revised frequently as the individual agents accumulate experience.

- Novelty niches—Such niches are associated with new markets, new technologies, new behaviors, and new institutions. The very act of filling a niche may provide new niches. The result is ongoing novelty.

- Out-of-equilibrium dynamics—Because new niches, new potentials, new possibilities, are continually created, the economy functions without attaining any optimum or global equilibrium. Improvements occur regularly.

Contemporary trends in economics

Complexity economics has a complex relation to previous work in economics and other sciences, and to contemporary economics. Complexity economics has been applied to many fields.

Intellectual predecessors

Complexity economics[4][5][6][7][8][9] draws inspiration from behavioral economics, Marxian economics, institutional economics/evolutionary economics, Austrian economics and the work of Adam Smith.[10] It also draws inspiration from other fields, such as statistical mechanics in physics, and evolutionary biology.

Applications

The theory of complex dynamic systems has been applied in diverse fields in economics and other decision sciences. These applications include capital theory,[11][12] game theory,[13] the dynamics of opinions among agents composed of multiple selves,[14] and macroeconomics.[15] In voting theory, the methods of symbolic dynamics have been applied by Donald G. Saari.[16] Complexity economics has attracted the attention of historians of economics.[17]

Complexity economics as mainstream, but non-orthodox

According to Colander (2000), Colander, Holt & Rosser (2004), and Davis (2008) contemporary mainstream economics is evolving to be more "eclectic",[18][19] diverse,[20][21][22] and pluralistic.[23] Colander, Holt & Rosser (2004) state that contemporary mainstream economics is "moving away from a strict adherence to the holy trinity---rationality, selfishness, and equilibrium", citing complexity economics along with recursive economics and dynamical systems as contributions to these trends.[24] They classify complexity economics as now mainstream but non-orthodox.[25][26]

Criticism

In 1995-1997 publications, Scientific American journalist John Horgan "ridiculed" the movement as being the fourth C among the "failed fads" of "complexity, chaos, catastrophe, and cybernetics".[2] In 1997, Horgan wrote that the approach had "created some potent metaphors: the butterfly effect, fractals, artificial life, the edge of chaos, self organized criticality. But they have not told us anything about the world that is both concrete and truly surprising, either in a negative or in a positive sense".[2][27][28]

Rosser "granted" Horgan "that it is hard to identify a concrete and surprising discovery (rather than "mere metaphor") that has arisen due to the emergence of complexity analysis" in the discussion journal of the American Economic Association, the Journal of Economic Perspectives.[2] Surveying economic studies based on complexity science, Rosser wrote that the findings, rather than being surprising, confirmed "already-observed facts".[2] Rosser wrote that there has been "little work on empirical techniques for testing dispersed agent complexity models".[2] Nonetheless, Rosser wrote that "there is a strain of common perspective that has been accumulating as the four C's of cybernetics, catastrophe, chaos and complexity emerged, which may now be reaching a critical mass in terms of influencing the thinking of economists more broadly".[2]

See also

Notes

- ^ Beinhocker, Eric D. The Origin of Wealth: Evolution, Complexity, and the Radical Remaking of Economics. Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business School Press, 2006.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Rosser, J. Barkley, Jr. "On the Complexities of Complex Economic Dynamics" Journal of Economic Perspectives, V. 13, N. 4 (Fall 1999): 169-192.

- ^ Arthur, Brian; Durlauf, Steven; Lane, David A (1997). "Introduction: Process and Emergence in the Economy". The Economy as an Evolving Complex System II. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley. http://www.santafe.edu/~wbarthur/Papers/ADLIntro.html. Retrieved 2008-08-26

- ^ Goodwin, Richard M. Chaotic Economic Dynamics. Oxford: Clarendon Press (1990)

- ^ Rosser, J. Barkley, Jr. From Catastrophe to Chaos: A General Theory of Economic Discontinuities Boston/Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

- ^ Benhabib, Jess (editor) Cycles and Chaos in Economic Equilibrium, Princeton University Press (1992).

- ^ Waldrop, M. Mitchell. Complexity: The Emerging Science at the Edge of Order and Chaos. New York:Touchstone (1992)

- ^ Saari, Donald. "Complexity of Simple Economics", Notices of the AMS. V. 42, N. 2 (Feb. 1995): 222-230

- ^ Ormerod, Paul (1998). Butterfly Economics: A New General Theory of Social and Economic Behavior. New York: Pantheon.

- ^ Complexity and the History of Economic Thought. Retrieved June 30, 2010: http://sandcat.middlebury.edu/econ/repec/mdl/ancoec/0804.pdf

- ^ Rosser, J. Barkley, Jr. "Reswitching as a Cusp Catastrophe", Journal of Economic Theory, V. 31 (1983): 182-193

- ^ Ahmad, Syed Capital in Economic Theory: Neo-classical, Cambridge, and Chaos. Brookfield: Edward Elgar (1991)

- ^ Sato, Yuzuru, Eizo Akiyama and J. Doyne Farmer. "Chaos in learning a simple two-person game", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, V. 99, N. 7 (2 Apr. 2002): 4748-4751

- ^ Krause, Ulrich. "Collective Dynamics of Faustian Agents", in Economic Theory and Economic Thought: Essays in honour of Ian Steedman (ed. by John Vint et al.) Routledge: 2010.

- ^ Flaschel, Peter and Christian R. Proano (2009). "The J2 Status of 'Chaos' in Period Macroeconomics Models"</A>, Studies in Nonlinear Dynamics & Econometrics, V. 13, N. 2. http://www.bepress.com/snde/vol13/iss2/art2/

- ^ Saari, Donald G. Chaotic Elections: A Mathematician Looks at Voting. American Mathematical Society (2001).

- ^ Bausor, Randall. "Qualitative dynamics in economics and fluid mechanics: a comparison of recent applications", in Natural Images in Economic Thought: Markets Read in Tooth and Claw (ed. by Philip Mirowski). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (1994).

- ^ "Economists today are not neoclassical according to any reasonable definition of the term. They are far more eclectic, and concerned with different issues than were the economists of the early 1900s, whom the term was originally designed to describe." Colander (2000, p. 130)

- ^ "Modern economics involves a broader world view and is far more eclectic than the neoclassical terminology allows." Colander (2000, p. 133)

- ^ "In our view, the interesting story in economics over the past decades is the increasing variance of acceptable views..." Colander, Holt & Rosser (2004, p. 487)

- ^ "In work at the edge, ideas that previously had been considered central to economics are being modified and broadened, and the process is changing the very nature of economics." Colander, Holt & Rosser (2004, p. 487)

- ^ "When certain members of the existing elite become open to new ideas, that openness allows new ideas to expand, develop, and integrate into the profession... These alternative channels allow the mainstream to expand, and to evolve to include a wider range of approaches and understandings... This, we believe, is already occurring in economics." Colander, Holt & Rosser (2004, pp. 488–489)

- ^ "despite an increasing pluralism on the mainstream economics research frontier..." Davis (2008, p. 353)

- ^ Colander, Holt & Rosser (2004, p. 485)

- ^ "The second (Santa Fe) conference saw a very different outcome and atmosphere than the first. No longer were mainstream economists defensively adhering to general equilibrium orthodoxy... By 1997, the mainstream accepted many of the methods and approaches that were associated with the complexity approach." Colander, Holt & Rosser (2004, p. 497) Colander, Holt & Rosser (2004, pp. 490–492) distinguish between orthodox and mainstream economics.

- ^ Davis (2008, p. 354)

- ^ Horgan, John, "From Complexity to Perplexity," Scientific American, June 1995, 272:6, 104 09.

- ^ Horgan, John, The End of Science: Facing the Limits of Knowledge in the Twilight of the Scientific Age. Paperback ed, New York: Broadway Books, 1997.

References

- Colander, David (2000). "The Death of Neoclassical Economics". Journal of the History of Economic Thought 22 (2): 127–143. doi:10.1080/10427710050025330.

- Colander, David; Holt, Richard P. F.; Rosser, Barkley J., Jr. (Oct. 2004). "The Changing Face of Mainstream Economics". Review of Political Economy 16 (4): 485–499. doi:10.1080/0953825042000256702. http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/content~db=all~content=a713997792~frm=titlelink.

- Davis, John B. (2008). "The turn in recent economics and return of orthodoxy". Cambridge Journal of Economics 32 (3): 349–366. doi:10.1093/cje/bem048. http://cje.oxfordjournals.org/content/32/3/349.abstract.

External links

- Santa Fe Institute A center of complexity science

- What Should Policymakers Know About Economic Complexity (PDF) Summary of complexity economics

Categories:- Economic theories

- Complex systems theory

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.