- Capitalism

-

"Liberal market economy" redirects here. For the ideology behind this economic system, see Economic liberalism.

Part of a series on

ConceptsEconomic theoriesOriginsPeopleVariantsRelated topicsMovements Capitalism Portal

Capitalism Portal

Philosophy Portal

Philosophy Portal

Economics Portal

Economics Portal

Politics Portal

Politics Portal

Capitalism is an economic system that became dominant in the Western world following the demise of feudalism.[1] There is no consensus on the precise definition nor on how the term should be used as a historical category.[2] There is general agreement that elements of capitalism include private ownership of the means of production, creation of goods or services for profit, competitive markets, and wage labor.[3][4] The designation is applied to a variety of historical cases, varying in time, geography, politics and culture.[5]

Karl Marx provided a differentia specifica for capitalism: People sell their labouring-power to a buyer, not to satisfy the personal needs of the buyer, but to augment the buyer's capital.[6] Other theorists define capitalism as a system in which all the means of production are privately owned. Theorists such as Mises, Rand, and Rothbard define capitalism as a market system with no interference by states, or laissez faire.[citation needed] Some theorists define capitalism as a system governed by capital accumulation regardless of legal ownership titles.[citation needed]

Economists, political economists and historians have taken different perspectives on the analysis of capitalism. Economists usually emphasize the degree that government does not have control over markets (laissez faire), and on property rights.[7][8] Most political economists emphasize private property, power relations, wage labor, class and emphasize capitalism as a unique historical formation.[9] Capitalism is generally viewed as encouraging economic growth.[10] The extent to which different markets are free, as well as the rules defining private property, is a matter of politics and policy, and many states have what are termed mixed economies.[9]

Capitalism gradually spread throughout Europe, and in the 19th and 20th centuries, it provided the main means of industrialization throughout much of the world.[5] Capitalism, by some definitions, is currently the world's dominant economic model.[citation needed]

Contents

Etymology and early usage

Other terms sometimes used for capitalism:

- Capitalist mode of production

- Economic liberalism[11]

- Free-enterprise economy[1][12]

- Free market[12][13]

- Laissez-faire economy[14]

- Market economy[15]

- Market liberalism[16][17]

- Self-regulating market[12]

Capital evolved from capitale, a late Latin word based on proto-Indo-European caput, meaning "head" — also the origin of chattel and cattle in the sense of movable property (only much later to refer only to livestock). Capitale emerged in the 12th to 13th centuries in the sense of funds, stock of merchandise, sum of money, or money carrying interest.[18][19][20] By 1283 it was used in the sense of the capital assets of a trading firm. It was frequently interchanged with a number of other words — wealth, money, funds, goods, assets, property and so on.[18]

The term capitalist refers to an owner of capital rather than an economic system, but shows earlier recorded use than the term capitalism, dating back to the mid-seventeenth century. The Hollandische Mercurius uses it in 1633 and 1654 to refer to owners of capital.[18] In French, Étienne Clavier referred to capitalistes in 1788,[21] six years before its first recorded English usage by Arthur Young in his work Travels in France (1792).[20][22] David Ricardo, in his Principles of Political Economy and Taxation (1817), referred to "the capitalist" many times.[23]

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, an English poet, used capitalist in his work Table Talk (1823).[24] Pierre-Joseph Proudhon used the term capitalist in his first work, What is Property? (1840) to refer to the owners of capital. Benjamin Disraeli used the term capitalist in his 1845 work Sybil.[20] Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels used the term capitalist (Kapitalist) in The Communist Manifesto (1848) to refer to a private owner of capital.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), the term capitalism was first used by novelist William Makepeace Thackeray in 1854 in The Newcomes, where he meant "having ownership of capital".[20] Also according to the OED, Carl Adolph Douai, a German-American socialist and abolitionist, used the term private capitalism in 1863.

The initial usage of the term capitalism in its modern sense has been attributed to Louis Blanc in 1850 and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon in 1861.[25] Marx and Engels referred to the capitalistic system (kapitalistisches System)[26][27] and to the capitalist mode of production (kapitalistische Produktionsform) in Das Kapital (1867).[28] The use of the word "capitalism" in reference to an economic system appears twice in Volume I of Das Kapital, p. 124 (German edition), and in Theories of Surplus Value, tome II, p. 493 (German edition). Marx did not extensively use the form capitalism, but instead those of capitalist and capitalist mode of production, which appear more than 2600 times in the trilogy Das Kapital.

Marx's notion of the capitalist mode of production is characterised as a system of primarily private ownership of the means of production in a mainly market economy, with a legal framework on commerce and a physical infrastructure provided by the state. No legal framework was available to protect the labourers, so exploitation by the companies was rife.[29][page needed] Engels made more frequent use of the term capitalism; volumes II and III of Das Kapital, both edited by Engels after Marx's death, contain the word "capitalism" four and three times, respectively. The three combined volumes of Das Kapital (1867, 1885, 1894) contain the word capitalist more than 2,600 times.

An 1877 work entitled Better Times by Hugh Gabutt and an 1884 article in the Pall Mall Gazette also used the term capitalism.[20] A later use of the term capitalism to describe the production system was by the German economist Werner Sombart, in his 1902 book The Jews and Modern Capitalism (Die Juden und das Wirtschaftsleben). Sombart's close friend and colleague, Max Weber, also used capitalism in his 1904 book The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (Die protestantische Ethik und der Geist des Kapitalismus).

Economic elements

Capitalist economics developed out of the interactions of the following elements.

A product is any good produced for exchange on a market. "Commodities" refers to standard products, especially raw materials such as grains and metals, that are not associated with particular producers or brands and trade on organized exchanges.

There are two types of products: capital goods and consumer goods. Capital goods (i.e., raw materials, tools, industrial machines, vehicles and factories) are used to produce consumer goods (e.g., televisions, cars, computers, houses) to be sold to others. The three inputs required for production are labor, land (i.e., natural resources, which exist prior to human beings) and capital goods. Capitalism entails the private ownership of the latter two — natural resources and capital goods — by a class of owners called capitalists, either individually, collectively or through a state apparatus that operates for a profit or serves the interests of capital owners.

Money was primarily a standardized medium of exchange, and final means of payment, that serves to measure the value all goods and commodities in a standard of value. It eliminates the cumbersome system of barter by separating the transactions involved in the exchange of products, thus greatly facilitating specialization and trade through encouraging the exchange of commodities. Capitalism involves the further abstraction of money into other exchangeable assets and the accumulation of money through ownership, exchange, interest and various other financial instruments. However, besides serving as a medium of exchange for labour, goods and services, money is also a store of value, similar to precious metals.

Labour includes all physical and mental human resources, including entrepreneurial capacity and management skills, which are needed to produce products and services. Production is the act of making products or services by applying labour power to the means of production.[30][31]

Types of capitalism

Economics  Economies by region

Economies by regionGeneral categories Microeconomics · Macroeconomics

History of economic thought

Methodology · Mainstream & heterodoxTechnical methods Mathematical economics

Game theory · Optimization

Computational · Econometrics

Experimental · National accountingFields and subfields Behavioral · Cultural · Evolutionary

Growth · Development · History

International · Economic systems

Monetary and Financial economics

Public and Welfare economics

Health · Education · Welfare

Population · Labour · Managerial

Business · Information

Industrial organization · Law

Agricultural · Natural resource

Environmental · Ecological

Urban · Rural · Regional · GeographyLists Business and Economics Portal There are many variants of capitalism in existence. All these forms of capitalism are based on production for profit, at least a moderate degree of market allocation and capital accumulation. The dominant forms of capitalism are listed here.

Mercantilism

A nationalist form of early capitalism where national business interests are tied to state interests, and consequently, the state apparatus is utilized to advance national business interests abroad. Mercantilism holds that the wealth of a nation is increased through a positive balance of trade with other nations.

Free-market capitalism

Free market capitalism consists of a free-price system where supply and demand are allowed to reach their point of equilibrium without intervention by the government. Productive enterprises are privately owned, and the role of the state is limited to protecting property rights.

Social market economy

Main article: Social marketA social market economy is a nominally free-market system where government intervention in price formation is kept to a minimum but the state provides significant social security, unemployment benefits and recognition of labor rights through national collective bargaining laws. The social market is based on private ownership of businesses.

State capitalism

State capitalism consists of state ownership of profit-seeking enterprises that operate in a capitalist manner in a market economy. Examples include corporatized government agencies or partial state ownership of shares in publicly listed firms. The term state capitalism has also been used to refer to an economy consisting of mainly private enterprises that are subjected to comprehensive national economic planning by the government, wherein the state intervenes in the economy to protect specific capitalist businesses (although this is usually referred to as state monopoly capitalism or corporate capitalism). Many socialists and anti-Stalinist leftists argue that the Soviet Union was state capitalist instead of socialist, since the state owned all the means of production, functioned as an enormous corporation, and exploited the working class.

Corporate capitalism

Corporate capitalism is a free or mixed market characterized by the dominance of hierarchical, bureaucratic corporations, which are legally required to pursue profit. State monopoly capitalism refers to a form of corporate capitalism where the state is used to benefit, protect from competition and promote the interests of dominant or established corporations.[citation needed]

Mixed economy

A largely market-based economy consisting of both public ownership and private ownership of the means of production. In practice, a mixed economy will be heavily slanted toward one extreme; most capitalist economies are defined as "mixed economies" to some degree and are characterized by the dominance of private ownership.[citation needed]

Other

Other variants of capitalism include:

- Crony capitalism

- Finance capitalism

- Financial capitalism

History

Economic trade for profit has existed since the second millennium BC.[32] However, capitalism in its modern form is usually traced to the Mercantilism of the 16th-18th Centuries.

Mercantilism

The period between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries is commonly described as mercantilism.[33] This period, the Age of Discovery, was associated with geographic exploration being exploited by merchant overseas traders, especially from England and the Low Countries; the European colonization of the Americas; and the rapid growth in overseas trade. Mercantilism was a system of trade for profit, although commodities were still largely produced by non-capitalist production methods.[5]

While some scholars see mercantilism as the earliest stage of capitalism, others argue that capitalism did not emerge until later. For example, Karl Polanyi, noted that "mercantilism, with all its tendency toward commercialization, never attacked the safeguards which protected [the] two basic elements of production—labor and land—from becoming the elements of commerce"; thus mercantilist attitudes towards economic regulation were closer to feudalist attitudes, "they disagreed only on the methods of regulation."

Moreover Polanyi argued that the hallmark of capitalism is the establishment of generalized markets for what he referred to as the "fictitious commodities": land, labor, and money. Accordingly, "not until 1834 was a competitive labor market established in England, hence industrial capitalism as a social system cannot be said to have existed before that date."[34]

Evidence of long-distance merchant-driven trade motivated by profit has been found as early as the second millennium BC, with the Old Assyrian merchants.[32] The earliest forms of mercantilism date back to the Roman Empire. When the Roman Empire expanded, the mercantilist economy expanded throughout Europe. After the collapse of the Roman Empire, most of the European economy became controlled by local feudal powers, and mercantilism collapsed there. However, mercantilism persisted in Arabia. Due to its proximity to neighboring countries, the Arabs established trade routes to Egypt, Persia, and Byzantium. As Islam spread in the seventh century, mercantilism spread rapidly to Spain, Portugal, Northern Africa, and Asia. Mercantilism finally revived in Europe in the fourteenth century, as mercantilism spread from Spain and Portugal.[35]

Among the major tenets of mercantilist theory was bullionism, a doctrine stressing the importance of accumulating precious metals. Mercantilists argued that a state should export more goods than it imported so that foreigners would have to pay the difference in precious metals. Mercantilists asserted that only raw materials that could not be extracted at home should be imported; and promoted government subsidies, such as the granting of monopolies and protective tariffs, were necessary to encourage home production of manufactured goods.

European merchants, backed by state controls, subsidies, and monopolies, made most of their profits from the buying and selling of goods. In the words of Francis Bacon, the purpose of mercantilism was "the opening and well-balancing of trade; the cherishing of manufacturers; the banishing of idleness; the repressing of waste and excess by sumptuary laws; the improvement and husbanding of the soil; the regulation of prices…"[36]

Similar practices of economic regimentation had begun earlier in the medieval towns. However, under mercantilism, given the contemporaneous rise of absolutism, the state superseded the local guilds as the regulator of the economy. During that time the guilds essentially functioned like cartels that monopolized the quantity of craftsmen to earn above-market wages.[37]

At the period from the eighteenth century, the commercial stage of capitalism originated from the start of the British East India Company and the Dutch East India Company.[38][39] These companies were characterized by their colonial and expansionary powers given to them by nation-states.[38] During this era, merchants, who had traded under the previous stage of mercantilism, invested capital in the East India Companies and other colonies, seeking a return on investment. In his "History of Economic Analysis," Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter reduced mercantilist propositions to three main concerns: exchange controls, export monopolism and balance of trade.[40]

Industrialism

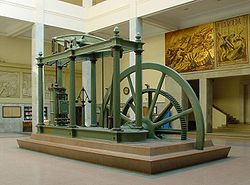

A Watt steam engine. The steam engine fuelled primarily by coal propelled the Industrial Revolution in Great Britain.[41]

A Watt steam engine. The steam engine fuelled primarily by coal propelled the Industrial Revolution in Great Britain.[41]

A new group of economic theorists, led by David Hume[42] and Adam Smith, in the mid 18th century, challenged fundamental mercantilist doctrines as the belief that the amount of the world’s wealth remained constant and that a state could only increase its wealth at the expense of another state.

During the Industrial Revolution, the industrialist replaced the merchant as a dominant actor in the capitalist system and effected the decline of the traditional handicraft skills of artisans, guilds, and journeymen. Also during this period, the surplus generated by the rise of commercial agriculture encouraged increased mechanization of agriculture. Industrial capitalism marked the development of the factory system of manufacturing, characterized by a complex division of labor between and within work process and the routine of work tasks; and finally established the global domination of the capitalist mode of production.[33]

Britain also abandoned its protectionist policy, as embraced by mercantilism. In the 19th century, Richard Cobden and John Bright, who based their beliefs on the Manchester School, initiated a movement to lower tariffs.[43] In the 1840s, Britain adopted a less protectionist policy, with the repeal of the Corn Laws and the Navigation Acts.[33] Britain reduced tariffs and quotas, in line with Adam Smith and David Ricardo's advocacy for free trade.

Karl Polanyi argued that capitalism did not emerge until the progressive commodification of land, money, and labor culminating in the establishment of a generalized labor market in Britain in the 1830s. For Polanyi, "the extension of the market to the elements of industry – land, labor and money – was the inevitable consequence of the introduction of the factory system in a commercial society."[44] Other sources argued that mercantilism fell after the repeal of the Navigation Acts in 1849.[43][45][46]

Keynesianism and neoliberalism

In the period following the global depression of the 1930s, the state played an increasingly prominent role in the capitalistic system throughout much of the world.

After World War II, a broad array of new analytical tools in the social sciences were developed to explain the social and economic trends of the period, including the concepts of post-industrial society and the welfare state.[33] This era was greatly influenced by Keynesian economic stabilization policies. The postwar boom ended in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and the situation was worsened by the rise of stagflation.[47]

Exceptionally high inflation combined with slow output growth, rising unemployment, and eventually recession to cause a loss of credibility in the Keynesian welfare-statist mode of regulation. Under the influence of Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman, Western states embraced policy prescriptions inspired by laissez-faire capitalism and classical liberalism.

In particular, monetarism, a theoretical alternative to Keynesianism that is more compatible with laissez-faire, gained increasing prominence in the capitalist world, especially under the leadership of Ronald Reagan in the US and Margaret Thatcher in the UK in the 1980s. Public and political interest began shifting away from the so-called collectivist concerns of Keynes's managed capitalism to a focus on individual choice, called "remarketized capitalism." [48] In the eyes of many economic and political commentators, the collapse of the Soviet Union brought further evidence of the superiority of market capitalism over communism.

Globalization

Although international trade has been associated with the development of capitalism for over five hundred years, some thinkers argue that a number of trends associated with globalization have acted to increase the mobility of people and capital since the last quarter of the 20th century, combining to circumscribe the room to maneuver of states in choosing non-capitalist models of development. Today, these trends have bolstered the argument that capitalism should now be viewed as a truly world system.[33] However, other thinkers argue that globalization, even in its quantitative degree, is no greater now than during earlier periods of capitalist trade.[49]

Neoclassical economic theory

Neoclassical economics explain capitalism as made up of individuals, enterprises, markets and government. According to their theories, individuals engage in a capitalist economy as consumers, labourers, and investors. As labourers, individuals may decide which jobs to prepare for, and in which markets to look for work. As investors they decide how much of their income to save and how to invest their savings. These savings, which become investments, provide much of the money that businesses need to grow.

Business firms decide what to produce and where this production should occur. They also purchase inputs (materials, labour, and capital). Businesses try to influence consumer purchase decisions through marketing and advertisement, as well as the creation of new and improved products. Driving the capitalist economy is the search for profits (revenues minus expenses). This is known as the profit motive, and it helps ensure that companies produce the goods and services that consumers desire and are able to buy. To be profitable, firms must sell a quantity of their product at a certain price to yield a profit. A business may lose money if sales fall too low or if its costs become too high. The profit motive encourages firms to operate more efficiently. By using less materials, labour or capital, a firm can cut its production costs, which can lead to increased profits.

An economy grows when the total value of goods and services produced rises. This growth requires investment in infrastructure, capital and other resources necessary in production. In a capitalist system, businesses decide when and how much they want to invest.

Income in a capitalist economy depends primarily on what skills are in demand and what skills are being supplied. Skills that are in scarce supply are worth more in the market and can attract higher incomes. Competition among workers for jobs — and among employers for skilled workers — help determine wage rates. Firms need to pay high enough wages to attract the appropriate workers; when jobs are scarce, workers may accept lower wages than they would when jobs are plentiful. Trade union and governments influence wages in capitalist systems. Unions act to represent their members in negotiations with employers over such things as wage rates and acceptable working conditions.

The market

The price (P) of a product is determined by a balance between production at each price (supply, S) and the desires of those with purchasing power at each price (demand, D). This results in a market equilibrium, with a given quantity (Q) sold of the product. A rise in demand would result in an increase in price and an increase in output.

The price (P) of a product is determined by a balance between production at each price (supply, S) and the desires of those with purchasing power at each price (demand, D). This results in a market equilibrium, with a given quantity (Q) sold of the product. A rise in demand would result in an increase in price and an increase in output.

Supply is the amount of a good or service produced by a firm and which is available for sale. Demand is the amount that people are willing to buy at a specific price. Prices tend to rise when demand exceeds supply, and fall when supply exceeds demand. In theory, the market is able to coordinate itself when a new equilibrium price and quantity is reached.

Competition arises when more than one producer is trying to sell the same or similar products to the same buyers. In capitalist theory, competition leads to innovation and more affordable prices. Without competition, a monopoly or cartel may develop. A monopoly occurs when a firm supplies the total output in the market; the firm can therefore limit output and raise prices because it has no fear of competition. A cartel is a group of firms that act together in a monopolistic manner to control output and raise prices.

Role of government

In a capitalist system, the government does not prohibit private property or prevent individuals from working where they please. The government does not prevent firms from determining what wages they will pay and what prices they will charge for their products. Many countries, however, have minimum wage laws and minimum safety standards.

Under some versions of capitalism, the government carries out a number of economic functions, such as issuing money, supervising public utilities and enforcing private contracts. Many countries have competition laws that prohibit monopolies and cartels from forming. Despite anti-monopoly laws, large corporations can form near-monopolies in some industries. Such firms can temporarily drop prices and accept losses to prevent competition from entering the market, and then raise them again once the threat of entry is reduced. In many countries, public utilities (e.g. electricity, heating fuel, communications) are able to operate as a monopoly under government regulation, due to high economies of scale.

Government agencies regulate the standards of service in many industries, such as airlines and broadcasting, as well as financing a wide range of programs. In addition, the government regulates the flow of capital and uses financial tools such as the interest rate to control factors such as inflation and unemployment.[50]

Democracy, the state, and legal frameworks

Private property

The relationship between the state, its formal mechanisms, and capitalist societies has been debated in many fields of social and political theory, with active discussion since the 19th century. Hernando de Soto is a contemporary economist who has argued that an important characteristic of capitalism is the functioning state protection of property rights in a formal property system where ownership and transactions are clearly recorded.[51]

According to de Soto, this is the process by which physical assets are transformed into capital, which in turn may be used in many more ways and much more efficiently in the market economy. A number of Marxian economists have argued that the Enclosure Acts in England, and similar legislation elsewhere, were an integral part of capitalist primitive accumulation and that specific legal frameworks of private land ownership have been integral to the development of capitalism.[52][53]

Institutions

New institutional economics, a field pioneered by Douglass North, stresses the need of a legal framework in order for capitalism to function optimally, and focuses on the relationship between the historical development of capitalism and the creation and maintenance of political and economic institutions.[54] In new institutional economics and other fields focusing on public policy, economists seek to judge when and whether governmental intervention (such as taxes, welfare, and government regulation) can result in potential gains in efficiency. According to Gregory Mankiw, a New Keynesian economist, governmental intervention can improve on market outcomes under conditions of "market failure", or situations in which the market on its own does not allocate resources efficiently.[55]

Market failure occurs when an externality is present and a market will either under-produce a product with a positive externalization or overproduce a product that generates a negative externalization. Air pollution, for instance, is a negative externalization that cannot be incorporated into markets as the world’s air is not owned and then sold for use to polluters. So, too much pollution could be emitted and people not involved in the production pay the cost of the pollution instead of the firm that initially emitted the air pollution. Critics of market failure theory, like Ronald Coase, Harold Demsetz, and James M. Buchanan argue that government programs and policies also fall short of absolute perfection. Market failures are often small, and government failures are sometimes large. It is therefore the case that imperfect markets are often better than imperfect governmental alternatives. While all nations currently have some kind of market regulations, the desirable degree of regulation is disputed.

Democracy

The relationship between democracy and capitalism is a contentious area in theory and popular political movements. The extension of universal adult male suffrage in 19th century Britain occurred along with the development of industrial capitalism, and democracy became widespread at the same time as capitalism, leading many theorists to posit a causal relationship between them, or that each affects the other. However, in the 20th century, according to some authors, capitalism also accompanied a variety of political formations quite distinct from liberal democracies, including fascist regimes, absolute monarchies, and single-party states,.[33]

While some thinkers argue that capitalist development more-or-less inevitably eventually leads to the emergence of democracy, others dispute this claim. Research on the democratic peace theory indicates that capitalist democracies rarely make war with one another[56] and have little internal violence. However critics of the democratic peace theory note that democratic capitalist states may fight infrequently and or never with other democratic capitalist states because of political similarity or stability rather than because they are democratic or capitalist.

Some commentators argue that though economic growth under capitalism has led to democratization in the past, it may not do so in the future, as authoritarian regimes have been able to manage economic growth without making concessions to greater political freedom.[57][58] States that have highly capitalistic economic systems have thrived under authoritarian or oppressive political systems. Singapore, which maintains a highly open market economy and attracts lots of foreign investment, does not protect civil liberties such as freedom of speech and expression. The private (capitalist) sector in the People's Republic of China has grown exponentially and thrived since its inception, despite having an authoritarian government. Augusto Pinochet's rule in Chile led to economic growth by using authoritarian means to create a safe environment for investment and capitalism.

In response to criticism of the system, some proponents of capitalism have argued that its advantages are supported by empirical research. Indices of Economic Freedom show a correlation between nations with more economic freedom (as defined by the indices) and higher scores on variables such as income and life expectancy, including the poor, in these nations.

Advocacy for capitalism

Economic growth

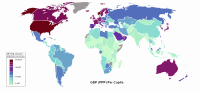

World's GDP per capita shows exponential growth since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution.[59]

World's GDP per capita shows exponential growth since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution.[59]

Many theorists and policymakers in predominantly capitalist nations have emphasized capitalism's ability to promote economic growth, as measured by Gross Domestic Product (GDP), capacity utilization or standard of living. This argument was central, for example, to Adam Smith's advocacy of letting a free market control production and price, and allocate resources. Many theorists have noted that this increase in global GDP over time coincides with the emergence of the modern world capitalist system.[60][61]

In years 1000–1820 world economy grew sixfold, 50 % per person. After capitalism had started to spread more widely, in years 1820–1998 world economy grew 50-fold, i.e., 9-fold per person.[62] In most capitalist economic regions such as Europe, the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, the economy grew 19-fold per person even though these countries already had a higher starting level, and in Japan, which was poor in 1820, to 31-fold, whereas in the rest of the world the growth was only 5-fold per person.[62]

Proponents argue that increasing GDP (per capita) is empirically shown to bring about improved standards of living, such as better availability of food, housing, clothing, and health care.[63] The decrease in the number of hours worked per week and the decreased participation of children and the elderly in the workforce have been attributed to capitalism.[64][65]

Proponents also believe that a capitalist economy offers far more opportunities for individuals to raise their income through new professions or business ventures than do other economic forms. To their thinking, this potential is much greater than in either traditional feudal or tribal societies or in socialist societies.

Political freedom

Milton Friedman stated that the economic freedom of capitalism is a requisite of political freedom. Friedman stated that centralized operations of economic activity is always accompanied by political repression. In his view, transactions in a market economy are voluntary, and the wide diversity that voluntary activity permits is a fundamental threat to repressive political leaders and greatly diminish power to coerce. Friedman's view was also shared by Friedrich Hayek and John Maynard Keynes, both of whom believed that capitalism is vital for freedom to survive and thrive.[66][67]

Self-organization

Austrian School economists have argued that capitalism can organize itself into a complex system without an external guidance or planning mechanism. Friedrich Hayek considered the phenomenon of self-organization as underpinning capitalism. Prices serve as a signal as to the urgent and unfilled wants of people, and the promise of profits gives entrepreneurs incentive to use their knowledge and resources to satisfy those wants. Thus the activities of millions of people, each seeking his own interest, are coordinated.[68]

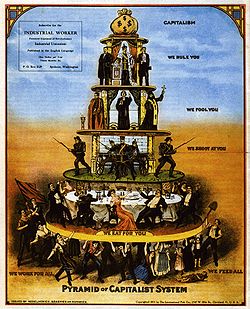

Criticisms of capitalism

Critics of capitalism associate it with: unfair distribution of wealth and power; a tendency toward market monopoly or oligopoly (and government by oligarchy); imperialism, counter-revolutionary wars and various forms of economic and cultural exploitation; repression of workers and trade unionists; social alienation; economic inequality; unemployment; and economic instability.

Notable critics of capitalism have included: socialists, anarchists, communists, national socialists, social democrats, technocrats, some types of conservatives, Luddites, Narodniks, Shakers and some types of nationalists.

Marxists have advocated a revolutionary overthrow of capitalism that would lead to socialism, before eventually transforming into communism. Many socialists consider capitalism to be irrational, in that production and the direction of the economy are unplanned, creating many inconsistencies and internal contradictions.[69] Labor historians and scholars such as Immanuel Wallerstein have argued that unfree labor — by slaves, indentured servants, prisoners, and other coerced persons — is compatible with capitalist relations.[70]

Many aspects of capitalism have come under attack from the anti-globalization movement, which is primarily opposed to corporate capitalism. Environmentalists have argued that capitalism requires continual economic growth, and that it will inevitably deplete the finite natural resources of the Earth.[71]

Many religions have criticized or opposed specific elements of capitalism. Traditional Judaism, Christianity, and Islam forbid lending money at interest, although alternative methods of banking have been developed. Some Christians have criticized capitalism for its materialist aspects[72] and its inability to account for the wellbeing of all people.[73][74]

See also

Notes

- ^ a b Capitalism. Encyclopedia Britannica. 2006.

- ^ Critical Issues in History. Lanham, Md: Rowman and Littlefield, 1999, p. 1

- ^ Heilbroner, Robert L. Capitalism. New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, Secound Edition (2008): http://www.dictionaryofeconomics.com/article?id=pde2008_C000053&edition=current&q=state%20capitalism&topicid=&result_number=2

- ^ Tormey, Simon. Anti-Capitalism. One World Publications, 2004. p. 10

- ^ a b c Scott, John (2005). Industrialism: A Dictionary of Sociology. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Marx, K. Capital, Progress Publishers (1954) [1977], Vol. I, Ch. 25, p580. Also Kerr Edition (1906), p678.

- ^ Tucker, Irvin B. (1997). Macroeconomics for Today. pp. 553.

- ^ Case, Karl E. (2004). Principles of Macroeconomics. Prentice Hall.

- ^ a b Stilwell, Frank. “Political Economy: the Contest of Economic Ideas.” First Edition. Oxford University Press. Melbourne, Australia. 2002.

- ^ "Economic systems". Encyclopedia Britannica 2007 Ultimate Reference Suite. (Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, 2009)

- ^ Werhane, P.H. (1994). "Adam Smith and His Legacy for Modern Capitalism". The Review of Metaphysics (Philosophy Education Society, Inc.) 47 (3).

- ^ a b c "free enterprise." Roget's 21st Century Thesaurus, Third Edition. Philip Lief Group 2008.

- ^ Mutualist.org. "...based on voluntary cooperation, free exchange, or mutual aid."

- ^ Barrons Dictionary of Finance and Investment Terms. 1995. p. 74

- ^ "Market economy", Merriam-Webster Unabridged Dictionary

- ^ "About Cato". Cato.org. http://www.cato.org/about.php. Retrieved 6 November 2008.

- ^ "The Achievements of Nineteenth-Century Classical Liberalism". http://www.cato.org/university/module10.html.

Although the term "liberalism" retains its original meaning in most of the world, it has unfortunately come to have a very different meaning in late twentieth-century America. Hence terms such as "market liberalism," "classical liberalism," or "libertarianism" are often used in its place in America.

- ^ a b c Braudel p.232

- ^ Etymology of "Cattle"

- ^ a b c d e James Augustus Henry Murray. "Capital". A New English Dictionary on Historical Principles. Oxford English Press. Vol 2. page 93.

- ^ e.g. "L'Angleterre a-t-elle l'heureux privilège de n'avoir ni Agioteurs, ni Banquiers, ni Faiseurs de services, ni Capitalistes?" in [Etienne Clavier] (1788) De la foi publique envers les créanciers de l'état: lettres à M. Linguet sur le n ° CXVI de ses annales p.19

- ^ Arthur Young. Travels in France

- ^ Ricardo, David. Principles of Political Economy and Taxation. 1821. John Murray Publisher, 3rd edition.

- ^ Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Tabel The Complete Works of Samuel Taylor Coleridge. page 267.

- ^ Braudel, Fernand. The Wheels of Commerce: Civilization and Capitalism 15–18 Century, Harper and Row, 1979, p.237

- ^ Karl Marx. Chapter 16: Absolute and Relative Surplus-Value. Das Kapital.

Die Verlängrung des Arbeitstags über den Punkt hinaus, wo der Arbeiter nur ein Äquivalent für den Wert seiner Arbeitskraft produziert hätte, und die Aneignung dieser Mehrarbeit durch das Kapital – das ist die Produktion des absoluten Mehrwerts. Sie bildet die allgemeine Grundlage des kapitalistischen Systems und den Ausgangspunkt der Produktion des relativen Mehrwerts.

The prolongation of the working-day beyond the point at which the labourer would have produced just an equivalent for the value of his labour-power, and the appropriation of that surplus-labour by capital, this is production of absolute surplus-value. It forms the general groundwork of the capitalist system, and the starting-point for the production of relative surplus-value.

- ^ Karl Marx. Chapter Twenty-Five: The General Law of Capitalist Accumulation. Das Kapital.

- Die Erhöhung des Arbeitspreises bleibt also eingebannt in Grenzen, die die Grundlagen des kapitalistischen Systems nicht nur unangetastet lassen, sondern auch seine Reproduktion auf wachsender Stufenleiter sichern.

- Die allgemeinen Grundlagen des kapitalistischen Systems einmal gegeben, tritt im Verlauf der Akkumulation jedesmal ein Punkt ein, wo die Entwicklung der Produktivität der gesellschaftlichen Arbeit der mächtigste Hebel der Akkumulation wird.

- Wir sahen im vierten Abschnitt bei Analyse der Produktion des relativen Mehrwerts: innerhalb des kapitalistischen Systems vollziehn sich alle Methoden zur Steigerung der gesellschaftlichen Produktivkraft der Arbeit auf Kosten des individuellen Arbeiters;

- ^ Saunders, Peter (1995). Capitalism. University of Minnesota Press. p. 1

- ^ Karl Marx. Das Kapital.

- ^ Ragan, Christopher T.S., and Richard G. Lipsey. Microeconomics. Twelfth Canadian Edition ed. Toronto: Pearson Education Canada, 2008. Print.

- ^ Robbins, Richard H. Global problems and the culture of capitalism. Boston: Allyn & Bacon, 2007. Print.

- ^ a b Warburton, David, Macroeconomics from the beginning: The General Theory, Ancient Markets, and the Rate of Interest. Paris: Recherches et Publications, 2003.p49

- ^ a b c d e f Burnham, Peter (2003). Capitalism: The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Politics. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Polanyi, Karl. The Great Transformation. Beacon Press, Boston.1944.p87

- ^ The Rise of Capitalism

- ^ Quoted in Sir George Clark, The Seventeenth Century (New York: Oxford University Press, 1961), p. 24.

- ^ Mancur Olson, The rise and decline of nations: economic growth, stagflation, and social rigidities (New Haven & London 1982).

- ^ a b Banaji, Jairus (2007). "Islam, the Mediterranean and the rise of capitalism". Journal Historical Materialism (Brill Publishers) 15: 47–74. doi:10.1163/156920607X171591.

- ^ Economic system :: Market systems. Encyclopedia Britannica. 2006. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/178493/economic-system/61117/Market-systems#toc242146.

- ^ Schumpeter, J.A. (1954) History of Economic Analysis

- ^ Watt steam engine image: located in the lobby of into the Superior Technical School of Industrial Engineers of a the UPM (Madrid)

- ^ Hume, David (1752). Political Discourses. Edinburgh: A. Kincaid & A. Donaldson.

- ^ a b "laissez-faire". http://www.bartleby.com/65/la/laissezf.html.

- ^ Polanyi, Karl. The Great Transformation, Beacon Press. Boston. 1944. p.78

- ^ "Navigation Acts". http://www.bartleby.com/65/na/NavigatA.html.

- ^ LaHaye, Laura (1993). "Mercantilism". Concise Encyclepedia of Economics. Fortune Encyclopedia of Economics. http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/Mercantilism.html.

- ^ Barnes, Trevor J. (2004). Reading economic geography. Blackwell Publishing. pp. 127. ISBN 063123554X.

- ^ Fulcher, James. Capitalism. 1st ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

- ^ Henwood, Doug (1 October 2003). After the New Economy. New Press. ISBN 1-56584-770-9.

- ^ "Capitalism." World Book Encyclopedia. 1988. 194. Print.

- ^ Hernando de Soto. "The mystery of capital". http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2001/03/desoto.htm. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- ^ Karl Marx. "Capital, v. 1. Part VIII: primitive accumulation". http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1867-c1/ch27.htm. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- ^ N. F. R. Crafts (April 1978). "Enclosure and labor supply revisited". Explorations in economic history 15 (15): 172–183. doi:10.1016/0014-4983(78)90019-0..we the say yes

- ^ North, Douglass C. (1990). Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Principles of Economics. Harvard University. 1997. pp. 10.

- ^ For the influence of capitalism on peace, see Mousseau, M. (2009) "The Social Market Roots of Democratic Peace", International Security 33 (4)

- ^ Mesquita, Bruce Bueno de (2005-09). "Development and Democracy". Foreign Affairs. http://www.foreignaffairs.org/20050901faessay84507/bruce-bueno-de-mesquita-george-w-downs/development-and-democracy.html. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- ^ Single, Joseph T. (2004-09). "Why Democracies Excel". New York Times. http://www10.nytimes.com/cfr/international/20040901facomment_v83n4_siegle-weinstein-halperin.html?_r=5&oref=slogin&oref=slogin&oref=slogin&oref=slogin. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- ^ Angus Maddison (2001). The World Economy: A Millennial Perspective. Paris: OECD. ISBN 92-64-18998-X.

- ^ Robert E. Lucas Jr.. "The Industrial Revolution: Past and Future". Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis 2003 Annual Report. http://www.minneapolisfed.org/pubs/region/04-05/essay.cfm. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- ^ J. Bradford DeLong. "Estimating World GDP, One Million B.C. – Present". http://www.j-bradford-delong.net/TCEH/1998_Draft/World_GDP/Estimating_World_GDP.html. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- ^ a b Martin Wolf, Why Globalization works, p. 43-45

- ^ Clark Nardinelli. "Industrial Revolution and the Standard of Living". http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/IndustrialRevolutionandtheStandardofLiving.html. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- ^ Barro, Robert J. (1997). Macroeconomics. MIT Press. ISBN 0262024365.

- ^ Woods, Thomas E. (5 April 2004). "Morality and Economic Law: Toward a Reconciliation". Ludwig von Mises Institute. http://www.mises.org/article.aspx?Id=1481. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- ^ Friedrich Hayek (1944). The Road to Serfdom. University Of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-32061-8.

- ^ Bellamy, Richard (2003). The Cambridge History of Twentieth-Century Political Thought. Cambridge University Press. pp. 60. ISBN 0-521-56354-2.

- ^ Walberg, Herbert (2001). Education and Capitalism. Hoover Institution Press. pp. 87–89. ISBN 0-8179-3972-5.

- ^ Brander, James A. Government policy toward business. 4th ed. Mississauga, Ontario: John Wiley & Sons Canada, Ltd., 2006. Print.

- ^ That unfree labor is acceptable to capital was argued during the 1980s by Tom Brass. See Towards a Comparative Political Economy of Unfree Labor (Cass, 1999). Marcel van der Linden. ""Labour History as the History of Multitudes", Labour/Le Travail, 52, Fall 2003, p. 235-244". http://www.historycooperative.org/journals/llt/52/linden.html. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- ^ McMurty, John (1999). The Cancer Stage of Capitalism. PLUTO PRESS. ISBN 0745313477.

- ^ "III. The Social Doctrine of the Church". The Vatican. http://www.vatican.va/archive/ENG0015/__P8C.HTM#-2FX. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- ^ Thomas Gubleton, archbishop of Detroit speaking in "Capitalism: A love story"[citation needed]

- ^ priest Peter Dougherty, speaking in "Capitalism: A love story"[citation needed]

References

- Bacher, Christian (2007) Capitalism, Ethics and the Paradoxon of Self-exploitation Grin Verlag. p. 2

- De George, Richard T. (1986) Business ethics p. 104

- Lash, Scott and Urry, John (2000). Capitalism. In Nicholas Abercrombie, S. Hill & BS Turner (Eds.), The Penguin dictionary of sociology (4th ed.) (pp. 36–40).

- Obrinsky, Mark (1983). Profit Theory and Capitalism. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 1. http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=4995059.

- Wolf, Eric (1982) Europe and the People Without History

- Wood, Ellen Meiksins (2002) The Origins of Capitalism: A Longer View London: Verso

- Thomas K. McCraw, "The Current Crisis and the Essence of Capitalism", The Montreal Review (August, 2011)

Further reading

- Abu-Lughod, Janet L. Before European Hegemony The World System A.D. 1250–1350. New York: Oxford UP, USA, 1991.

- Ackerman, Frank; Lisa Heinzerling (24 August 2005). Priceless: On Knowing the Price of Everything and the Value of Nothing. New Press. pp. 277. ISBN 1565849817.

- Buchanan, James M.. Politics Without Romance.

- Braudel, Fernand. Civilization and Capitalism: 15th – 18 Century.

- Bottomore, Tom (1985). Theories of Modern Capitalism.

- H. Doucouliagos and M. Ulubasoglu (2006). "Democracy and Economic Growth: A meta-analysis". School of Accounting, Economics and Finance Deakin University Australia.

- Coase, Ronald (1974). The Lighthouse in Economics.

- Demsetz, Harold (1969). Information and Efficiency.

- Fulcher, James (2004). Capitalism.

- Friedman, Milton (1952). Capitalism and Freedom.

- Galbraith, J.K. (1952). American Capitalism.

- Böhm-Bawerk, Eugen von (1890). Capital and Interest: A Critical History of Economical Theory. London: Macmillan and Co..

- Harvey, David (1990). The Political-Economic Transformation of Late Twentieth Century Capitalism.. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 0-631-16294-1.

- Hayek, Friedrich A. (1975). The Pure Theory of Capital. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-32081-2.

- Hayek, Friedrich A. (1963). Capitalism and the Historians. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Heilbroner, Robert L. (1966). The Limits of American Capitalism.

- Heilbroner, Robert L. (1985). The Nature and Logic of Capitalism.

- Heilbroner, Robert L. (1987). Economics Explained.

- Cryan, Dan (2009). Capitalism: A Graphic Guide.

- Josephson, Matthew, The Money Lords; the great finance capitalists, 1925–1950, New York, Weybright and Talley, 1972.

- Luxemburg, Rosa (1913). The Accumulation of Capital.

- Marx, Karl (1886). Capital: A Critical Analysis of Capitalist Production.

- Mises, Ludwig von (1998). Human Action: A Treatise on Economics. Scholars Edition.

- Rand, Ayn (1986). Capitalism: The Unknown Ideal. Signet.

- Reisman, George (1996). Capitalism: A Treatise on Economics. Ottawa, Illinois: Jameson Books. ISBN 0-915463-73-3.

- Resnick, Stephen (1987). Knowledge & Class: a Marxian critique of political economy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Rostow, W. W. (1960). The Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Schumpeter, J. A. (1983). Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy.

- Scott, Bruce (2009). The Concept of Capitalism. Springer. pp. 76. ISBN 3642031099.

- China GDP – Dr. Fengbo Zhang introduced the Western economics, GDP and SNA system to China, replaced Soviet Union's MPS system.

- Scott, John (1997). Corporate Business and Capitalist Classes.

- Seldon, Arthur (2007). Capitalism: A Condensed Version. London: Institute of Economic Affairs.

- Sennett, Richard (2006). The Culture of the New Capitalism.

- Smith, Adam (1776). An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations.

- De Soto, Hernando (2000). The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-01614-6.

- Strange, Susan (1986). Casino Capitalism.

- Wallerstein, Immanuel. The Modern World System.

- Weber, Max (1926). The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism.

External links

Categories:- Capitalism

- Capitalist systems

- Economic systems

- Economic ideologies

- Economies

- Economic liberalism

- Ideologies

- Social philosophy

- Political economy

- Individualism

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.