- Das Kapital

-

This article is about the book. For the album by Capital Inicial, see Das Kapital (album).

Capital: Critique of Political Economy

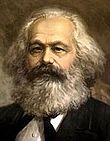

Author(s) Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels (editor) Original title Das Kapital, Kritik der politischen Ökonomie Country Germany Language German, subsequently into many languages Genre(s) Economics, Political theory Publisher Verlag von Otto Meisner Publication date 1867, 1885, 1894 Das Kapital, Kritik der politischen Ökonomie (German pronunciation: [das kapiˈtaːl]; Capital: Critique of Political Economy), by Karl Marx, is a critical analysis of capitalism as political economy, meant to reveal the economic laws of the capitalist mode of production, and how it was the precursor of the socialist mode of production.

Part of a series on Marxism  Social sciencesAlienation · Bourgeoisie

Social sciencesAlienation · Bourgeoisie

Base and superstructure

Class consciousness

Commodity fetishism

Exploitation · Human nature

Ideology · Proletariat

Private property

Reification · Cultural hegemony

Relations of production

Scientific socialism

ImmiserationCapitalist mode of production

Socialist mode of production

Capital accumulation

Commodity (Marxism)

Marxian economics

Communism

Economic determinism

Labour power · Law of value

Means of production

Mode of production

Perspectives on Capitalism

Productive forces

Surplus labour · Surplus value

Transformation problem

Wage labour · Crisis theoryHistoryCategoriesAll categorised articlesCommunism portal

Contents

Themes

In Capital: Critique of Political Economy (1867), Karl Marx proposes that the motivating force of capitalism is in the exploitation of labour, whose unpaid work is the ultimate source of profit and surplus value. The employer can claim right to the profits (new output value), because he or she owns the productive capital assets (means of production), which are legally protected by the State through property rights. In producing capital (money) rather than commodities (goods and services), the workers continually reproduce the economic conditions by which they labour. Capital proposes an explanation of the “laws of motion” of the capitalist economic system, from its origins to its future, by describing the dynamics of the accumulation of capital, the growth of wage labour, the transformation of the workplace, the concentration of capital, commercial competition, the banking system, the decline of the profit rate, land-rents, et cetera.

The critique of the political economy of capitalism proposes that:

- The commodity is the foundational “cell-form” (trade unit) of a capitalist society, which has commercial value for the owner of the means of production. Moreover, because commerce, as a human activity, implied no morality beyond that required to buy and sell goods and services, the growth of the market system made discrete entities of the economic, the moral, and the legal spheres of human activity in society; hence, subjective moral value is separate from objective economic value. Subsequently, political economy — the just distribution of wealth and “political arithmetick” about taxes — became three discrete fields of human activity: Economics, Law, and Ethics, politics and economics divorced.

- “The economic formation of society [is] a process of natural history", thus it is possible for a political economist to objectively study the scientific laws of capitalism, given that its expansion of the market system of commerce had objectified human economic relations; the use of money (cash nexus) voided religious and political illusions about its economic value, and replaced them with commodity fetishism, the belief that an object (commodity) has inherent economic value. Because societal economic formation is an historical process, no one person could control or direct it, thereby creating a global complex of social connections among capitalists; thus, the economic formation (individual commerce) of a society precedes the human administration of an economy (organised commerce).

- The structural contradictions of a capitalist economy, the gegensätzliche Bewegung, describe the contradictory movement originating from the two-fold character of labour; not the class struggle between labour and capital, the wage labourer and the owner of the means of production. These capitalist economy contradictions operate “behind the backs” of the capitalists and the workers, as a result of their activities, and yet remain beyond their perceptions as men and women and as social classes.[1]

- The economic crises (recession, depression, etc.) that are rooted in the contradictory character of the economic value of the commodity (cell-unit) of a capitalist society, are the conditions that propitiate proletarian revolution; which the Communist Manifesto (1848) collectively identified as a weapon, forged by the capitalists, which the working class “turned against the bourgeoisie, itself”.

- In a capitalist economy, technological improvement and its consequent increased production augment the amount of material wealth (use value) in society, whilst simultaneously diminishing the economic value of the same wealth, thereby diminishing the rate of profit — a paradox characteristic of economic crisis in a capitalist economy; “poverty in the midst of plenty” consequent to over-production and under-consumption.

After decades of economic study and preparatory work (especially regarding the theory of surplus value) the first volume appeared in 1867: The production process of capital. After Marx's death in 1883, Friedrich Engels introduced, from manuscripts and the first volume; Volume II: The circulation process of capital in 1885; and Volume III: The overall process of capitalist production in 1894. These three volumes are collectively known as Das Kapital.

Capital: Critique of Political Economy

Capital Volume I

Main article: Capital, Volume ICapital, Volume I (1867), by Karl Marx, is a critical analysis of capitalism as political economy, meant to reveal the economic laws of the capitalist mode of production, how it was the precursor of the socialist mode of production, and of the class struggle rooted in the capitalist social relations of production. The first of three volumes of Das Kapital, Kritik der politischen Ökonomie (Capital: Critique of Political Economy) was published on 14 September 1867, and was the sole volume published in Marx’s lifetime.

Capital Volume II

Main article: Capital, Volume IICapital, Volume 2, subtitled The Process of Circulation of Capital, was prepared by Friedrich Engels from notes left by Karl Marx and published in 1885. It is divided into three parts:[1] The Metamorphoses of Capital and Their Circuits The Turnover of Capital The Reproduction and Circulation of the Aggregate Social Capital In Volume II, the main ideas behind the marketplace are to be found: how value and surplus-value are realized. Its dramatis personae, not so much the worker and the industrialist (as in Volume I), but rather the money owner (and money lender), the wholesale merchant, the trader and the entrepreneur or 'functioning capitalist.' Moreover, workers appear in Volume II, essentially as buyers of consumer goods and, therefore, as sellers of the commodity labour power, rather than producers of value and surplus-value (although, this latter quality, established in Volume I, remains the solid foundation on which the whole of the unfolding analysis is based). Reading Volume II is of monumental significance to understanding the theoretical construction of Marx's whole argument. Marx himself quite precisely clarified this place, in a letter sent to Engels on 30 April 1868: 'In Book 1. . . we content ourselves with the assumption that if in the self-expansion process €100 becomes €110, the latter will find already in existence in the market the elements into which it will change once more. But now we investigate the conditions under which these elements are found at hand, namely the social intertwining of the different capitals, of the component parts of capital and of revenue (= s).' This intertwining, conceived as a movement of commodities and of money, enabled Marx to work out at least the essential elements, if not the definitive form of a coherent theory of the trade cycle, based upon the inevitability of periodic disequilibrium between supply and demand under the capitalist mode of production (Mandel, 1978, Intro to Vol. II of Capital). Volume II of Capital has indeed been not only a 'sealed book', but also a forgotten one. To a large extent, it remains so to this very day. Part 3 is the point of departure for a topic given its Marxist treatment later in detail by, among others, Rosa Luxemburg.

Capital Volume III

Main article: Capital, Volume IIICapital, Volume 3, subtitled The Process of Capitalist Production as a Whole, was prepared by Friedrich Engels from notes left by Karl Marx and published in 1894. It is in seven parts:

- The conversion of Surplus Value into Profit and the rate of Surplus Value into the rate of Profit

- Conversion of Profit into Average Profit

- The Law of the Tendency of the Rate of Profit to Fall

- Conversion of Commodity Capital and Money Capital into Commercial Capital and Money-Dealing Capital (Merchant's Capital)

- Division of Profit Into Interest and Profit of Enterprise, Interest Bearing Capital.

- Transformation of Surplus-Profit into Ground Rent.

- Revenues and Their Sources

The work is best known today for part 3, which in summary says that as the organic fixed capital requirements of production rise as a result of advancements in production generally, the rate of profit tends to fall. This result, which orthodox Marxists believe is a principal contradictory characteristic leading to an inevitable collapse of the capitalist order, was held by Marx and Engels to, as a result of various contradictions in the capitalist mode of production, result in crises whose resolution necessitates the emergence of an entirely new mode of production as the culmination of the same historical dialectic that led to the emergence of capitalism from prior forms.

Intellectual influences

The purpose of Capital: Critique of Political Economy (1867) was a scientific foundation for the politics of the modern labour movement; the analyses were meant “to bring a science, by criticism, to the point where it can be dialectically represented” and so “reveal the law of motion of modern society” to describe how the capitalist mode of production was the precursor of the socialist mode of production. The argument is a critique of the classical economics of Adam Smith, David Ricardo, John Stuart Mill, and Benjamin Franklin, drawing on the dialectical method that G.W.F. Hegel developed in The Science of Logic and The Phenomenology of Spirit; other intellectual influences upon Capital were the French socialists Charles Fourier, Comte de Saint-Simon, and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon; and the Greek philosophers, especially Aristotle.

At university, Marx wrote a dissertation comparing the philosophy of nature in the works of the pre-Socratic philosophers Democritus (ca. 460–370 BC) and Epicurus (341–270 BC); from which academic speculation proposes is the derivation of the logical architecture of Capital: Critique of Political Economy, because exchange value, the “syllogisms” (C-M-C' and M-C-M') for simple commodity circulation, and the circulation of value as capital, derive from the Politics and the Nicomachean Ethics, by Aristotle. Moreover, the description of machinery, under capitalist relations of production, as “self-acting automata” derives from Aristotle’s speculations about inanimate instruments capable of obeying commands as the condition for the abolition of slavery. In the nineteenth century, Karl Marx’s research of the available politico-economic literature required twelve years, usually in the British Library, London.

Capital, Volume IV

At the time of his death (1883) Karl Marx had prepared the manuscript for Capital, Volume IV, a critical history of theories of surplus value of his time, the nineteenth century. The philosopher Karl Kautsky (1854–1938) published a partial edition of Marx’s surplus-value critique, and later published a full, three-volume edition as Theorien über den Mehrwert (Theories of Surplus Value, 1905–1910); the first volume was published in English as A History of Economic Theories (1952).[2]

Publication

Capital, Volume I (1867) was published in Marx’s lifetime, but he died, in 1883, before completing the manuscripts for Capital, Volume II (1885) and Capital, Volume III (1894), which friend and collaborator Friedrich Engels edited and published as the work of Karl Marx. The first translated publication of Capital: Critique of Political Economy was in Imperial Russia, in March 1872. It was the first foreign publication, the English edition appeared in 1887.[3] Despite Tsarist censorship proscribing “the harmful doctrines of socialism and communism”, the Russian censors considered Capital as a “strictly scientific work” of political economy the content of which did not apply to monarchic Russia, where “capitalist exploitation” had never occurred, and was officially dismissed, given that “that very few people in Russia will read it, and even fewer will understand it”; nonetheless, Karl Marx acknowledged that Russia was the country where Capital “was read and valued more than anywhere.” The Russian edition was the fastest selling. 3,000 copies were sold in 1 year while the German edition took 5 years to sell 1,000 (15 times slower). [4]

Translations

The foreign editions of Capital: Critique of Political Economy (1867), by Karl Marx, include a Russian translation by the revolutionary Mikhail Bakunin (1814–1876). An English translation by Samuel Moore and Edward Aveling was reissued in the 1970s by Progress Publishers in Moscow; recent English translations are by David McLellan and Ben Fowkes.

See also

- Accumulation by dispossession

- Analytical Marxism

- Étienne Balibar

- Eduard Bernstein

- G.A. Cohen

- Capital (economics)

- Capital accumulation

- Capitalism

- Commodity fetishism

- Cost of capital

- Crisis theory

- Culture of capitalism

- History of theory of capitalism

- Immiseration thesis

- Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism

Online editions

- Capital, Volume I: The Process of Production of Capital

- Capital, Volume I in audio format, from LibriVox.

- Capital, Volume I 1906 edition, downloadable text and pdf from Google Books

- Capital, Volume II: The Process of Circulation of Capital

- Capital, Volume III: The Process of Capitalist Production as a Whole

- "Capital, Volume IV": Theories of Surplus Value

Synopses

- Reading Marx's Capital -- Series of video lectures by professor David Harvey

- (PDF) Fredrick Engels' Synopsis of Capital. I. Marxists. 1868. pp. 54. http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/download/Engels_Synopsis_of_Capital.pdf. (The first 4 parts (chapters) of the eventual 7 of Volume I)

- (PDF) Otto Ruhle's Abridgement of Karl Marx's Capital : A Critique of Political Economy. Workers' Liberty. pp. 48. http://www.workersliberty.org/system/files/fscache/FB/9B/FB9B4414.

Footnotes

- ^ Marx, Karl. Capital: The Process of Capitalist Production. 3d German edition (tr.), p. 53.

- ^ Columbia Encyclopedia, Fifth Edition (1994) p. 1707.

- ^ Ostler, Nicholas. Empires of the Word: A Language History of the World. HarperCollins: London and New York, 2005.

- ^ A People's Tragedy: The Russian Revolution 1891-1924 (London 1996) p. 139

Further reading

- Althusser, Louis and Balibar, Étienne. Reading Capital. London: Verso, 2009.

- Louis Althusser (1969) How to Read Marx's Capital from Marxism Today, October 1969, 302-305. Originally appeared (in French) in Humanité on April 21, 1969.

- Bottomore, Tom, ed. A Dictionary of Marxist Thought. Oxford: Blackwell, 1998.

- Fine, Ben. Marx's Capital. 5th ed. London: Pluto, 2010.

- Harvey, David. A Companion to Marx's Capital. London: Verso, 2010.

- Harvey, David. The Limits of Capital. London: Verso, 2006.

- Mandel, Ernest. Marxist Economic Theory. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1970.

- Capital: An Abridged Edition, Karl Marx (Author), David McLellan (Editor), 2008, Oxford Paperbacks; Abridged edition, Oxford, UK. ISBN 978-0-199535-70-5

- Postone, Moishe. Time, Labor, and Social Domination: A Reinterpretation of Marx's Critical Theory. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

- Wheen, Francis. Marx's Das Kapital--A Biography. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0802143945.

External links

- Annotations, Explanations and Clarifications to Capital. Will help with understanding the early concepts.

- Wage Labour and Capital. An earlier document that deals with many of the ideas later expanded in Das Kapital.

- First in a series of accessible columns on Capital by Joseph Choonara in Socialist Worker

- Reading Marx’s Capital with David Harvey A university open course, consisting of a close reading of the text of Marx's Capital Volume I in 13 video lectures.

The works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels Marx Scorpion and Felix (1837), Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right (1843), On the Jewish Question (1843), Notes on James Mill (1844), Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844 (1844), Theses on Feuerbach (1845), The Poverty of Philosophy (1847), Wage-Labor and Capital (1847), The Class Struggles in France, 1848–1850 (1850), The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon (1852), Grundrisse (1857), Preface to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (1859), Theories of Surplus Value, 3 volumes (1862), Value, Price and Profit (1865), Capital, Volume I (Das Kapital) (1867), The Civil War in France (1871), Critique of the Gotha Program (1875), Notes on Wagner (1880), Mathematical manuscripts of Karl Marx (1968)Marx and Engels The German Ideology (1845), The Holy Family (1845), Manifesto of the Communist Party (1848), Writings on the U.S. Civil War (1861), Capital, Volume II [posthumous to Marx, published by Engels] (1885), Capital, Volume III [posthumous to Marx, published by Engels] (1894)Engels The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844 (1844), The Peasant War in Germany (1850), Revolution and Counter-Revolution in Germany (1852), Anti-Dühring (1878), Socialism: Utopian and Scientific (1880), Dialectics of Nature (1883), The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State (1884), Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy (1886)Categories:- 1867 books

- 1885 books

- 1894 books

- Books about capitalism

- Economics books

- Marxism

- Political books

- Unfinished books

- Communist books

- Books by Karl Marx

- Books in political philosophy

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.