- Operation Eagle Claw

-

"Operation Rice Bowl" redirects here. It is not to be confused with the Catholic Relief Services program to end hunger and poverty.

Operation Eagle Claw Part of Iran Hostage Crisis

Overview of the wreckage at the Desert One base in Iran.Date 24–25 April 1980 Location Tabas, Iran Result U.S. rescue operation failed with casualties; collision of aircraft at Desert One. Belligerents  United States

United States Iran

IranCommanders and leaders  Jimmy Carter

Jimmy Carter

Maj. Gen. James B. Vaught

Maj. Gen. James B. Vaught

Col. James H. Kyle

Col. James H. Kyle

Col. Charles A. Beckwith

Col. Charles A. Beckwith Ruhollah Khomeini

Ruhollah Khomeini

Abolhassan Banisadr

Abolhassan BanisadrCasualties and losses 8 killed

4 wounded

1 helicopter and 1 transport aircraft destroyed

5 helicopters abandoned/capturednone Civilian casualties: 1 killed

44 capturedOperation Eagle Claw (or Operation Evening Light or Operation Rice Bowl)[1] was an American military operation ordered by President Jimmy Carter to attempt to put an end to the Iran hostage crisis by rescuing 52 Americans held captive at the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, Iran on 24 April 1980. The humiliating public debacle that ensued damaged American prestige worldwide and is believed by many, including Carter himself, to have played a major role in his defeat in the 1980 presidential election.[2]

The plan called for a minimum of six helicopters; eight were sent in.[3] Two helicopters could not navigate through a very fine sand cloud (a haboob) which forced one helicopter to crash land and the other to return to the aircraft carrier USS Nimitz (CVN-68). Six helicopters reached the initial rendezvous point, Desert One, but one of them had damaged its hydraulic systems. The spares were on one of the two helicopters that had aborted. From the early planning stages, it had been determined that if fewer than six operational helicopters were available, then the mission would be automatically aborted, even though only four were absolutely necessary for the operation.[3] In a move still debated,[4] the commanders on the scene requested to abort the mission; Carter gave his approval.

As the U.S. force prepared to leave Iran, one of the helicopters crashed into a C-130 Hercules transport aircraft containing fuel and a group of servicemen. The resulting fire destroyed the two aircraft involved[3] and resulted in the remaining helicopters being left behind and the deaths of eight American servicemen. Operation Eagle Claw was one of the first missions conducted by Delta Force.[5]

Contents

Planning and preparation

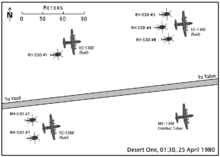

The operation was designed as a complex two-night mission. The first stage of the mission involved delivering a U.S. Army Delta Force rescue team to a small staging site inside Iran, near Tabas in Yazd Province (formerly in the south of the Khorasan province). The site, named Desert One, was to be used as a temporary airstrip for the three USAF special operations MC-130E Combat Talon I penetration/transport aircraft and three EC-130E Hercules, each of the latter equipped with a pair of collapsible fuel bladders containing 6,000 U.S. gallons of jet fuel. Desert One would then become a staging base for eight Navy RH-53D Sea Stallion minesweeper helicopters. The RH-53s, flown by US Marine Corps personnel off the aircraft carrier USS Nimitz (CVN-68) in the nearby Indian Ocean, would then transport the rescue team to Tehran. These operations were covered by Carrier Air Wing 8 (CVW-8) aboard Nimitz and CVW-14 aboard the USS Coral Sea (CV-43). For this operation, the aircraft bore special black-red-black identification stripes on their right wings.

After flying in under radar and landing at Desert One, the C-130s would off-load men and equipment and refuel the arriving helicopters, which would, in turn, undertake the rescue operation. The helicopters would fly the ground troops to the Desert Two "hide site" near Tehran the same night, where the helicopters would be concealed. The next night, the rescue force would be transported in trucks to the embassy by CIA agents, overpower the guards, and escort the hostages across Roosevelt Boulevard (the main road in front of the embassy) to Shahid Shiroudi Stadium, where the helicopters would retrieve the entire contingent. The Joint Task Force commander was U.S. Army Major General James B. Vaught, while the fixed-wing and overall air mission commander was Colonel James H. Kyle, the helicopter commander Marine Lieutenant Colonel Edward R. Seiffert, and Delta Force commander Col. Charlie Beckwith.

The Tehran CIA Special Activities Division paramilitary team, led by retired Special Forces officer Richard J. Meadows, had two assignments: to obtain information about the hostages and the embassy grounds, and to transport the rescuers from Desert Two to the embassy grounds in pre-staged vehicles. In reality, the most important information came from an embassy cook who was released by the Iranians. He was discovered on a flight from Tehran at the last minute by another CIA officer, and confirmed that the hostages were centrally located in the embassy compound – this was a key piece of information long sought by the planners.

The assault on the embassy was to occur after eliminating electrical power in the area to disrupt any military response by the Iranians. AC-130 gunships were to orbit overhead to provide supporting fire. The helicopters were to transport the rescuers and hostages from Shahid Shiroudi Stadium to Manzariyeh Air Base outside of Tehran (34°58′58″N 50°48′20″E / 34.98278°N 50.80556°E). There a Ranger force would seize the airfield to permit C-141 transports to land in advance of the rescue to transport the contingent from Iran under the protection of fighter planes.

On 1 April, three weeks before the operation, a USAF combat control team officer, Major John T. Carney Jr., was flown in a Twin Otter to the Desert One site by two CIA officers for a clandestine survey of an airstrip. Despite their casual approach to the mission, he successfully surveyed the airstrip, installed remotely operated infrared lights and a strobe to outline a landing pattern for pilots, and took soil samples to determine the load-bearing properties of the desert surface. At that time, the floor was hard-packed sand, but in the intervening three weeks, an ankle-deep layer of powdery sand was deposited by sandstorms.[6]

Execution of the mission

Only the delivery of the rescue force, equipment and fuel by the MC-130E Combat Talons (call signs Dragon 1 to 3) and EC-130Es (Republic 4 to 6), all flown by Combat Talon crews, went according to plan. The special operations transports took off from their staging base at Masirah Island near Oman and were refueled in-flight by KC-135 tankers just off the coast of Iran.

Dragon 1 landed at 22:45 local time after the hidden lights were activated. The landing was made under blacked-out conditions using the same improvised infrared landing light system as that installed by Carney on the airstrip, visible only through night vision goggles. The heavily loaded Dragon 1 required four passes to determine that there were no obstructions on the airstrip[7] and that it could squeeze into its small confines. The landing resulted in substantial wing damage to the Talon that later required it be rebuilt "from the ground up", but no one was hurt and the Talon remained flyable. Dragon 1 off-loaded Kyle, a USAF combat control team (CCT) led by Carney, Beckwith and part of his 120 Delta operators, 12 Rangers of a roadblock team, and 15 Iranian and American Persian-speakers, most of whom would act as truck drivers. The CCT immediately established a parallel landing zone north of the dirt road and set out TACAN beacons to guide the helicopters. The second and third MC-130s landed and discharged the remainder of the Delta Force operators, after which Dragon 1 and 2 took off at 23:15 to make room for the EC-130s and the eight RH-53D Sea Stallion helicopters (Bluebeard 1 to 8).

Bluebeard 6 was grounded and abandoned in the desert when its Marine pilots interpreted a sensor indication as a cracked rotor blade. Its crew was picked up by Bluebeard 8. Then, the remaining helicopters ran into an unexpected weather phenomenon known as a haboob (fine particles of sand suspended to a milky consistency in the air following dissipation of a thunderstorm). Bluebeard 5 flew into the haboob, but abandoned the mission and returned to the Nimitz when erratic flight control instrumentation made navigating without visual reference points impossible, just 25 minutes from clear air. The scattered formation reached Desert One, 50 to 90 minutes behind schedule. Bluebeard 2 arrived at Desert One with a malfunctioning second-stage hydraulics system (which powers the number-one automatic flight control system and a portion of the primary flight controls) leaving one hydraulics system to control the aircraft. (Bluebeards 2 and 8, which were later abandoned, now serve with the Iranian Navy.)

Soon after the first crews landed and began securing Desert One, a tanker truck apparently smuggling fuel was blown up nearby by a shoulder-fired rocket as it tried to escape the site. The passenger in the tanker truck was killed, but the truck's driver managed to escape in an accompanying pickup truck; when the tanker truck was evaluated to be engaged in clandestine smuggling, the driver was not considered to pose a security threat to the mission.[8] The resulting fire illuminated the nighttime landscape for many miles around, and actually provided a visual guide to Desert One for the disoriented and dehydrated incoming helicopter crews. A civilian Iranian bus with a driver and 43 passengers traveling on the same road, which served as the runway for the aircraft, was forced to halt at approximately the same time and detained aboard Republic 3[clarification needed].[9]

With only five Sea Stallions remaining to transport the men and equipment to Desert Two, which Beckwith considered was the abort threshold for the mission, the various commanders reached a stalemate. Helicopter commander Seiffert refused to use Bluebeard 2 on the mission, while Beckwith refused to reduce the size of his rescue force. Beckwith failed to incorporate intelligence from a Canadian diplomatic source into a "bump plan"[clarification needed]; additionally, he anticipated losing additional helicopters at later stages, especially as they were notorious for failing on cold starts and they were to be shut down for almost 24 hours at Desert Two. Kyle recommended to Vaught that the mission be aborted. The recommendation was passed on by satellite radio up to the President. After two and a half hours on the ground, the abort order was received.

Debacle

Fuel consumption calculations showed that the extra 90 minutes idling on the ground had made fuel critical for one of the EC-130s. When it became clear that only six helicopters would arrive at Desert One, Kyle had authorized the EC-130s to transfer 1,000 U.S. gallons from the bladders to their own main fuel tanks, but Republic 4 had already expended all of its bladder fuel refueling three of the helicopters and had none to transfer. To make it to the tanker refueling track without running out of fuel, it had to leave immediately, and was already loaded with part of the Delta force. In addition, RH-53 Bluebeard 4 needed additional fuel, requiring it be moved to the opposite side of the road.

To accomplish both actions, Sea Stallion Bluebeard 3 had to be moved from directly behind the EC-130. The helicopter could not be moved by ground taxi,[10] and had to be moved by "air taxi" (flying a short distance at low speed and altitude). An Air Force CCT marshaller attempted to direct the maneuver from in front of the helicopter, but was blasted by desert sand churned up by the rotor. As the marshaller attempted to back away, the pilot of Bluebeard 3 perceived he was drifting backward (engulfed in a dust cloud, the pilot only had the CCT marshaller as a point of reference) and thus attempted to "correct" this situation by applying forward stick in order to maintain the same distance from the rearward moving marshaller. The RH-53 struck the vertical stabilizer of the EC-130 with its main rotor and crashed into the wing root of the EC-130.[11]

In the ensuing explosion and fire, eight servicemen died: five USAF aircrew in the C-130, and three USMC aircrew aboard the RH-53, with only the helicopter pilot and co-pilot (both badly burned) surviving. During the following frantic evacuation by the C-130s, the helicopter crews attempted to retrieve their classified mission documents and destroy the helicopters, but Colonel Beckwith ordered them to get on the C-130s or be left behind. The helicopter crews boarded the C-130s. Five RH-53 helicopters were left behind mostly intact, some damaged by shrapnel. The Iranians gained at least four of them.

The C-130s carried the remaining forces back to the intermediate airfield at Masirah Island, where two C-141 medical evacuation aircraft from the Night Two staging base at Wadi Abu Shihat, Egypt (referred to as Wadi Kena by the US Forces due to its location near Qena) 26°33′18″N 33°07′58″E / 26.555058°N 33.132877°E picked up the injured personnel, helicopter crews, Rangers and Delta Force members, and returned to Wadi Kena. The injured were then transported to Ramstein Air Base, Germany. The Tehran CIA team left Iran, unaware that their presence had been compromised.

Aftermath

The White House announced the failed rescue operation at 1:00AM the following day. The embassy hostages were subsequently scattered across Iran to make a second rescue attempt impossible. Iranian Army investigators found nine bodies, eight Americans and one Iranian civilian (which Iran used to criticize the White House's announcement that "there were no Iranian casualties"[citation needed]). 44 Iranian civilians were interviewed[clarification needed] and gave eyewitness accounts of the operation.[8]

The failure of the various services to work together cohesively eventually forced the establishment of a new multi-service organization several years later. The United States Special Operations Command (USSOCOM) became operational on 16 April 1987. Each service now has its own Special Operations Forces under the overall control of USSOCOM. For example, the Army has its own Army Special Operations Command (USASOC), which controls the Army Special Operations Forces (ARSOF). The Air Force special ops units that supplied the MC-130 elements of the rescue attempt were awarded the AF Outstanding Unit Award for both that year and the next, had the initial squadron of nine HH-53 Pave Low helicopters transferred from Military Airlift Command to its jurisdiction for long-range low-level night flying operations, and became co-hosts at its home base of Hurlburt Field with the Air Force Special Operations Command (AFSOC).

The lack of well-trained Army helicopter pilots who were capable of the low-level night flying needed for modern special forces missions prompted the creation of the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment (SOAR) (Night Stalkers). In addition to the creation of the 160th SOAR, the DOD now trains many helicopter pilots of the USAF,USN,USMC and USA in lowlevel penetration, in-flight refueling and use of Night-vision goggles. H-47,H-53,H-60 and V-22 aircraft all include special operations capabilities and in-flight refueling.

Planning for a second rescue mission attempt was authorized under the name Project Honey Badger shortly after the first failed. Plans and exercises were conducted, but the manpower and aircraft requirements grew to involve nearly a battalion of troops, more than fifty helicopters, and such contingencies as transporting a 12-ton bulldozer to rapidly clear a blocked runway. Even though numerous rehearsal exercises were successful, the failure of the helicopters during the first attempt resulted in development of a subsequent concept involving only fixed-wing STOL aircraft capable of flying from the United States to Iran using aerial refueling, then recovering[clarification needed] aboard an aircraft carrier for medical treatment of wounded.

The concept, called Operation Credible Sport, was developed, but never implemented. It called for a modified Hercules, the YMC-130H, outfitted with rocket thrusters fore and aft to allow an extremely short landing and take-off in Amjadieh Stadium. Three aircraft were modified under a rushed secret program. The first fully modified aircraft crashed during a demonstration at Duke Field at Eglin Air Force Base on 29 October 1980, when its landing braking rockets were fired too soon. The misfire caused a hard touchdown that tore off the starboard wing and started a fire. All on board survived without injury. The impending change of administration in the White House forced the abandonment of this project.[12]

Despite the failure of Credible Sport, the Honey Badger exercises continued until after the 1980 U.S. presidential election, when they became moot. Even so, numerous special operations techniques and applications were developed which became part of the emerging Special Operations Command repertoire.

President Carter continued to attempt to secure the release of the hostages before the end of his presidency. Despite extensive last-minute negotiations, he did not succeed. On 20 January 1981, minutes after Carter's term in office ended, the 52 U.S. captives held at the U.S. embassy in Iran were released, ending the 444-day Iran hostage crisis.[13]

Retired Chief of Naval Operations Admiral James L. Holloway III led the official investigation in 1980 into the causes of the failure of the operation on behalf of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. The Holloway Report primarily cited deficiencies in mission planning, command and control, and inter-service operability, and provided a catalyst to reorganize the Department of Defense, and the Goldwater-Nichols Act of 1986.[14]

A memorial honoring the eight Americans who lost their lives during the rescue attempt is located in the Arlington National Cemetery.[15]

Iranian response

Some hardline Iranians claimed that United States' failure on this mission was a form of divine intervention. They especially note the similarity of this incident to the story of Abraha in attacking the Kaaba in the Year of the Elephant. This event is referred to in Qur'an, sura 105, Al-Fil, and is discussed in its related tafsir. Many Iranian writers and journalists also compared the two events.[16][17][18][19]

Units involved in the operation

Units known to have participated:

United States Air Force

- 1st Special Operations Wing: 1st (MC-130), 8th (MC-130), and 16th Special Operations Squadrons (AC-130)

- SF-121 Personnel involved (1 per aircraft)are still classified.

- RED HORSE units, and numerous support organizations

- 1st Combat Communications Squadron

United States Army

- 1st Special Forces Operational Detachment-Delta (“Delta Force”), including Col. Charlie Beckwith, Maj. Peter Schoomaker, Maj. William G. Boykin, and MSG Eric L. Haney

- 75th Ranger Regiment

- United States Army Special Forces

- USS Nimitz (CVN-68) with Carrier Air Wing 8 and escorts (USS California (CGN-36), USS South Carolina (CGN-37), USS Texas (CGN-39) and USS Reeves (CG-24))

- USS Wichita (AOR-1)

- USS Coral Sea (CV-43) and escorts, USS Cook (FF-1083)[20] with Carrier Air Wing 14

- USS Okinawa (LPH-3)

- USS St. Louis (LKA-116), USS Frederick (LST-1184) Amphibious Support.

- Marine Aviation Weapons Tactics Squadron 1 (MAWTS-1)

- Helicopter Mine Countermeasures Squadron 16 (HM-16) aboard Nimitz

See also

References

- Citations

- ^ AFSOC.af.mil

- ^ "Jimmy Carter: Iran hostage rescue should have worked". USA Today. 17 September 2010. http://www.usatoday.com/news/washington/2010-09-17-iran-hostages-jimmy-carter_N.htm.

- ^ a b c The Desert One Debacle

- ^ Operation Eagle Claw, 1980: A Case Study In Crisis Management and Military Planning

- ^ Gabriel, Richard A. (1985). Military Incompetence: Why the American Military Doesn't Win, Hill and Wang, ISBN 0-374-52137-9, pp. 106–116. Overall, the Holloway Commission blamed the ad hoc nature of the task force and an excessive degree of security, both of which intensified command-and-control problems.

- ^ Bottoms, Mike (2007). "Carney receives Simons Award" (pdf). Tip of the Spear. United States Special Operations Command Public Affairs Office. pp. 26–31. http://www.specialoperations.net/Spear/tipspear.pdf. Retrieved 11 November 2010. The "box four and one" pattern acted like a gun sight, with the distant fifth light at the end of the runway lined up in the center of the near four lights positioned at the approach end. The box provided a touchdown area and the far light marked the end of the rollout area.

- ^ This was done by use of a Forward looking infrared (FLIR) pass before attempting to land.

- ^ a b Bowden, Mark (2006). Guests Of The Ayatollah: The First Battle In America's War With Militant Islam. Atlantic Monthly Press. ISBN 0-87113-925-1.

- ^ It was originally planned to simulate a head-on accident between the tanker and the bus, flying the bus passengers out of Iran aboard Dragon 3 and then returning them to Manzaniyeh on the second night.

- ^ Either because of a deflated nose gear tire, because of the layer of soft sand, or both. It had originally been positioned behind the EC-130 by a flight technique in which its nose gear was held off the ground while it rolled on its main gear.

- ^ Thigpen 2001, p. 226

- ^ James Bancroft. "The Hostage Rescue Attempt In Iran, 24–25 April 1980". http://rescueattempt.tripod.com/id1.html. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ^ "Iran Hostage Crisis ends – History.com This Day in History – January 20, 1981". History.com. http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/1/20. Retrieved 8 June 2010.

- ^ "The Holloway Report" (PDF). http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB63/doc8.pdf. Accessed 31 March 2007.

- ^ The eight were: USAF members Majors Harold L. Lewis, Richard L. Bakke, and Lyn D. McIntosh, Captain Charles T. McMillan II, and Technical Sergeant Joel C. Mayo; and Marine Corps members Staff Sergeant Dewey L. Johnson, Sergeant John D. Harvey, and Corporal George N. Holmes, Jr.

- ^ Tabas Event and the Magical Helps, 1984, by Ministry of Islamic Thoughts and Guidance, Iran, in Arabic.

- ^ "Tabas, An implementation of the Elephant Surah, 1991". http://www.nlai.ir/Default.aspx?tabid=1667. by Imam Khomeini following muslim university students group. 191 pages, in Persian.

- ^ "The Loss of US In Tabas, April 26, 2003". http://www.hawzah.net/hawzah/magazines/magart.aspx?magazinenumberid=4670&id=35829. in Persian. Accessed 19 July 2009.

- ^ "Tabas Desert, A Repetition of the Elephant Surah, April 25, 2009". http://yazdanparast.ws/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=401:1388-02-05-09-26-47&catid=66:1388-01-31-13-54-43. in Persian. Accessed 19 July 2009.

- ^ DD214 Decorations/Sailor Present.

- Bibliography

- Kamps, Charles (2006). "Operation Eagle Claw: The Iran Hostage Rescue Mission". Air & Space Power Journal. http://www.airpower.maxwell.af.mil/apjinternational/apj-s/2006/3tri06/kampseng.html.

- Olausson, Lars, Lockheed Hercules Production List 1954–2005, Såtenäs, Sweden, annually, no ISBN.

- Kyle, Col. James H., USAF (Ret.) (1990). The Guts to Try. New York: Orion Books. ISBN 0-517-57714-3.

- Lenahan, Rod (1998). Crippled Eagle: A Historical Perspective Of U.S. Special Operations 1976–1996. Narwhal Press. ISBN 1-886391-22-x.

- Beckwith, Col. Charlie A., US Army (Ret.) (2000). Delta Force: The Army's Elite Counter Terrorist Unit. Avon. ISBN 0-380-80939-7.

- Haney, Eric (2002). Inside Delta Force: The Story Of America's Elite Counter Terrorist Unit. Random House. ISBN 0-385-33603-9.

- Bowden, Mark (May 2006). "The Desert One Debacle". The Atlantic Monthly. http://www.theatlantic.com/doc/200605/iran-hostage.

- Bowden, Mark (2006). Guests Of The Ayatollah: The First Battle In America's War With Militant Islam. Atlantic Monthly Press. ISBN 0-87113-925-1.

- Online

- USAF College of Aerospace Doctrine, Research and Education. Air & Power Course: Operation Eagle Claw. United States of America: US Air Force.[dead link]

External links

- "The Desert One Debacle" – The Atlantic, May 2006

- Modern Warfare: Special Operations, Operation Eagle Claw – The first part of a series of articles on Kuro5hin

- Pictorial overview

- Airman magazine – Interviews with surviving participants link is broken

- The Holloway Report – The official DoD investigation into the incident

Categories:- Conflicts in 1980

- Iran–United States relations

- History of Iran

- Military history of the United States (1900–1999)

- Operations involving American special forces

- Battles involving the United States

- Battles involving Iran

- United States Army Rangers

- United States Marine Corps in the 20th century

- 1980 in Iran

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.