- Military history of Canada

-

Military history of Canada

This article is part of a series Conflicts Beaver Wars

French and Indian Wars

American Civil War

War of 1812

Fenian raids

Wolseley Expedition

North-West Rebellion

Boer War

First World War

Russian Civil War

Spanish Civil War

Second World War

Cold War

Korean War

Vietnam War

Gulf War

Afghanistan War

Iraq War

Intervention in LibyaHistory of.. Militia · Crown & Forces

Army · Navy · Air ForceLists Conflicts · Operations

Peacekeeping · BibliographyCanadian Forces portal The military history of Canada comprises hundreds of years of armed actions in the territory encompassing modern Canada, and the role of the Canadian military in conflicts and peacekeeping worldwide. For thousands of years, the area that would become Canada was the site of sporadic intertribal wars among Aboriginal people. Although not without conflict, European/Canadian (c. late 15th - early 16th centuries) interactions with First Nations and Inuit populations were relatively peaceful. The Inuit had more limited interaction with European settlers during that early period.[1]

Starting in the 17th and 18th century, Canada was the site of four colonial wars between New France and New England which spanned almost seventy years, as each allied with various First Nation groups. In 1763, after the final colonial war - the French and Indian War - the British emerged victorious and the Canadien civilians, whom the British hoped to assimilate, were declared "British Subjects". After the passing of the Quebec Act in 1774, giving Canadiens their first charter of rights under the new regime, new challenges soon arose when the northern colonies chose not to join the American Revolution and remained loyal to the British crown. The victorious Americans looked to extend their republic and launched invasions in 1775 and in 1812. On both occasions, the Americans were rebuffed by British and local forces; however, this threat would remain well into the 19th century and partially facilitated Canadian Confederation in 1867.

After Confederation, and amid much controversy, a full-fledged Canadian military was created. Canada, however, remained a British colony, and Canadian forces joined their British counterparts in the Second Boer War, and the First World War. While independence followed the Statute of Westminster, Canada's links to Britain remained strong, and the British once again enjoyed Canadian support in the Second World War. Since the Second World War, however, Canada has been committed to multilateralism and has gone to war only within large multinational coalitions such as in the Korean War, the Gulf War, the Kosovo War, and the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan. Canada has also played an important role in UN peacekeeping operations worldwide and has cumulatively committed more troops than any other country.

History

First Nations

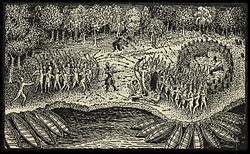

Based on a drawing by Samuel de Champlain from his 1609 voyage, this engraving depicts a battle between Iroquois and Algonquian| tribes near the southern end of Lake Champlain.

Based on a drawing by Samuel de Champlain from his 1609 voyage, this engraving depicts a battle between Iroquois and Algonquian| tribes near the southern end of Lake Champlain.

The first conflicts between Europeans and Native peoples may have occurred around 1006, when parties of Norsemen attempted to establish permanent settlements along the coast of Newfoundland. According to Norse sagas, the native Beothuk (called skraelings or skraelingars by the Norse) responded so ferociously that the newcomers eventually withdrew and gave up their original intentions to settle. Among later European settlers, the First Nations developed a reputation for violence and savagery. The Natives gave no heed to the idea of surrender, and tended to torture and kill those who did so.[2]

Prior to the arrival of Europeans, some First Nations warfare tended to be formal and ritualistic, and entail relatively few casualties.[3] But there is also evidence of much more violent warfare, even the complete genocide of some groups by others, such as the total displacement of the Dorset culture of Newfoundland by the Beothuk mentioned above, as well as by the Inuit in other regions. There is no evidence of genetic or cultural continuity, so the Dorset are presumed to have simply been wiped out. Just prior to French settlement in the St. Lawrence River valley, the local Iroquoian peoples were completely eradicated, probably in warfare with their neighbors. Study of whether any of these people, who had several large towns along the St. Lawrence River, survived the 16th century is inconclusive. After Europeans arrived, fighting tended to be bloodier and more decisive, especially as tribes became caught up in the economic and military rivalries of the European settlers. By the end of the seventeenth century, the East Coast First Nations rapidly adopted the use of firearms, supplanting the traditional bow.[4] While a skilled warrior could dodge an incoming arrow, and wooden armour offered some measure of protection against arrows, nothing could protect them from a bullet. Even wounds to limbs from these large-calibre, low velocity bullets eventually proved fatal. The adoption of firearms significantly increased the number of fatalities. The bloodshed, involved in native conflicts, was also dramatically increased by the uneven distribution of firearms and horses among Native groups.

Native tribes became important allies of the French and English in the struggle for North American hegemony during the 17th and 18th centuries; these alliances escalated the violence. Scalping, which is now believed to have existed before the arrival of the Europeans, became more common as the Europeans demanded the presentation of scalps as evidence of their military success.[5]

Early French settlements

Map showing the approximate location of major tribes and settlements.[6]

Map showing the approximate location of major tribes and settlements.[6]

The French under Samuel de Champlain founded settlements at Annapolis Royal in 1605 and Quebec City in 1608, quickly joining pre-existing Native alliances that brought them into conflict with other indigenous inhabitants. For example, soon after the founding of Quebec City, Champlain joined a Huron-Algonkian alliance against the Iroquois Confederacy. In the earliest battle, superior French firepower rapidly dispersed a massed groups of Natives. The Iroquois changed tactics by integrating their hunting skills and their intimate knowledge of the terrain with their use of firearms obtained from the Dutch; therefore, they developed a highly effective form of guerrilla warfare, and were soon a formidable threat to all but the handful of fortified cities. As well, as the French gave few guns to their Native allies, the Iroquois waged devastating warfare against the tribes of the Great Lakes region. For the first century of its existence the chief threat to the inhabitants of New France came from the Iroquois Confederacy, and particularly from its eastern-most people, the Mohawks. While the majority of tribes in the region were allies of the French, the Iroquois were aligned first with the Dutch, and, after the ceding of New Netherland to England, with the British, and received their weapons and support.

The French and Iroquois Wars continued intermittently until 1703, with great brutality on both sides. In response to the Iroquois threat, the French government dispatched the Carignan-Salières Regiment, the first group of uniformed professional soldiers to set foot on what is today Canadian soil. After peace was attained, this regiment was disbanded in Canada. The soldiers settled in the St. Lawrence valley and, in the late 17th century, formed the core of the Compagnies Franches de la Marine, the local militia. Later, militias were developed on the larger seigneuries.

Canada was colonised by two major European powers that were historically at odds with each other, and it was inevitable that this age-old tension would spill over into Canada; during the 17th and 18th centuries, there was almost continuous conflict between the colonizing powers in Canada.

Two years after the French founded Annapolis Royal, the English began their first settlement, at Jamestown, Virginia to the south. From these original footholds, much larger colonies of Acadia and other colonies of New France would emerge. The French colony of Canada on the Saint Lawrence River was based primarily on the fur trade and enjoyed only lukewarm support from the French monarchy. The colonies of New France grew only slowly amidst the tough and unyielding geographical and climatic circumstances. The more favourably located New England colonies to the south developed more diversified economies and flourished. There were four colonial wars between New France and New England before the British were victorious.

By the 1750s, when the economic, political, and military rivalries came to a head in the struggle of the last colonial war - the French and Indian War - the total population of the 13 English colonies was 1,500,000, whereas that of their French rivals to the north was only about 70,000. As a result, outside of their strongholds of Quebec City and Louisbourg, the French were forced to employ both guerrilla warfare tactics, largely borrowed from the Natives. The guerilla form of fighting became known as la petite guerre.[7]

17th Century

During the 17th century, there were several skirmishes between the two great powers. During the Anglo-French War (1627–1629), under Charles I of England, by 1629 the Kirkes took Quebec City, Sir James Stewart of Killeith, Lord Ochiltree planted a colony on Cape Breton Island at Baleine, and William Alexander, 1st Earl of Stirling established the first incarnation of “New Scotland” at Port Royal, Nova Scotia. This set of British triumphs which left Cape Sable as the only major French holding in North America was not destined to last.[8] Charles I’s haste to make peace with France on the terms most beneficial to him meant that the new North American gains would be bargained away in the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye (1632).[9]

During this time when Nova Scotia briefly became a Scottish Colony, there were three battles between the Scots and the French: one at St. John; another at Cape Sable Island; and the other at Baleine, Nova Scotia.

Civil War in Acadia

Siege of St. John (1745) - d'Aulnay defeats La Tour in Acadia

Siege of St. John (1745) - d'Aulnay defeats La Tour in Acadia

During this time, Acadia was plunged into what some historians have described as a civil war in Acadia (1640–1645). The war was between Port Royal, where Governor of Acadia Charles de Menou d'Aulnay de Charnisay was stationed, and present-day Saint John, New Brunswick, where Governor Charles de Saint-Étienne de la Tour was stationed.[10]

In the war, there were four major battles. la Tour attacked d'Aulnay at Port Royal in 1640.[11] In response to the attack, D'Aulnay sailed out of Port Royal to establish a five month blockade of La Tour's fort at Saint John, which La Tour eventually defeated (1643). La Tour attacked d'Aulnay again at Port Royal in 1643. d'Aulnay and Port Royal ultimately won the war against La Tour with the 1645 siege of Saint John.[12] After d'Aulnay died (1650), La Tour re-established himself in Acadia.

King William's War

Before the Battle of Quebec, Governor Frontenac famously rebuffs the English envoys: "The only response I have for your general is through the muzzles of my cannons." Watercolour on commercial board.

Before the Battle of Quebec, Governor Frontenac famously rebuffs the English envoys: "The only response I have for your general is through the muzzles of my cannons." Watercolour on commercial board.

During King William's War, the next most serious threat to Quebec in the seventeenth century came in 1690 when, alarmed by the attacks of the petite guerre, the New England colonies sent an armed expedition north, under Sir William Phips, to capture the source of the problems: Quebec itself. This expedition was poorly organized and had little time to achieve its objective, having arrived in mid-October, shortly before the St Lawrence would freeze over. The expedition was responsible for eliciting one of the most famous pronouncements in Canadian military history. When called on by Phips to surrender, the aged Governor Frontenac, then serving his second term, replied "I will answer ... only with the mouths of my cannon and the shots of my muskets." After a single abortive landing on the Beauport shore to the east of the city, the English force withdrew down the icy waters of the St Lawrence.

During the war, the military conflicts in Acadia included: Battle at Chedabucto (Guysborough); Battle of Port Royal (1690); a naval battle in the Bay of Fundy (Action of 14 July 1696); Raid on Chignecto (1696) and Siege of Fort Nashwaak (1696).

In 1695, Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville was called upon to attack the English stations along the Atlantic coast of Newfoundlandin the Avalon Peninsula Campaign. Iberville sailed with his three vessels to Placentia (Plaisance), the French capital of Newfoundland. Both English and French fishermen exploited the Grand Banks fishery from their respective settlements on Newfoundland under the sanction of the treaty of 1687, but the purpose of the new French expedition of 1696 was nevertheless to expel the English from Newfoundland. Iberville and his men left Placentia on November 1, 1696, and marched overland to Ferryland, 50 miles (80 km) south of St John's. Nine days later, Iberville joined with naval forces and both detachments began the march north to the English capital, which surrendered on November 30, 1696, following a brief siege. After setting fire to St John's, Iberville's Canadians almost totally destroyed the English fisheries along the eastern shore of Newfoundland. Small raiding parties terrorized the hamlets hidden away in remote bays and inlets, burning, looting, and taking prisoners. By the end of March 1697, only Bonavista and Carbonear remained in English hands. In four months of raids, Iberville was responsible for the destruction of 36 settlements.

At the end of the war England returned the territory to France in the Treaty of Ryswick.

18th century

Further information: French and Indian WarsDuring the 18th century, the British-French struggle in Canada intensified as the rivalry between the mother countries worsened in Europe. As concerns grew, the French government poured more and more military spending into its North American colonies. Expensive garrisons were maintained at distant fur trading posts, the fortifications of Quebec City were improved and augmented, and a new fortified town was built on the east coast of Île Royale, or Cape Breton Island—the fortress of Louisbourg, the so-called "Dunkirk of the North."

The first of four colonial wars - King William's War was fought at the end of the 17th century. Three times during the 18th century, New France and New England were at war with one another. The second and third colonal wars, Queen Anne's War and King Georges War, were local off-shoots of larger European conflicts—the War of the Spanish Succession (1702–13), the War of the Austrian Succession (1744–48). The last, the French and Indian War (Seven Years' War), started in the Ohio Valley. The petite guerre of the Canadiens left a trail of terror and devastation through the northern towns and villages of New England, sometimes reaching as far south as Virginia.[13] The war also spread to the forts along the Hudson Bay shore.

Queen Anne's War

Queen Anne's War, the British Conquest of Acadia, took place in 1710 when a British force managed to capture Port Royal, the capital of Acadia in present-day Nova Scotia. As a result, France was forced to cede control of mainland Nova Scotia to Britain in the Treaty of Utrecht (1713), leaving present-day New Brunswick in disputed territory and Prince Edward Island, and Cape Breton Island in the hands of the French. British possession of Hudson Bay was guaranteed by the same treaty.

During Queen Anne's War, military conflicts in Nova Scotia included: the Raid on Grand Pre; the Siege of Port Royal (1707); the Siege of Port Royal (1710) and the Battle of Bloody Creek (1711).

Dummer's War

During the escalation that preceded Dummer's War (1722–1725), Mi'kmaq raided the new fort at Canso, Nova Scotia (1720). Under potential siege, in May 1722, Lieutenant Governor John Doucett took 22 Mi'kmaq hostage at Annapolis Royal to prevent the capital from being attacked.[14] In July 1722 the Abenaki and Mi'kmaq created a blockade of Annapolis Royal with the intent of starving the capital.[15] The natives captured 18 fishing vessels and prisoners in the area stretching from present-day Yarmouth to Canso. They also seized prisoners and vessels from the Bay of Fundy.

As a result of the escalating conflict, Massachusetts Governor Samuel Shute officially declared war on the Abenaki on July 22, 1722.[16] The first battle of Dummer's War happened in the Nova Scotia theatre.[17] In response to the blockade of Annapolis Royal, at the end of July 1722, New England launched a campaign to end the blockade and retrieve over 86 New England prisoners taken by the natives. One of these operations resulted in the Battle at Jeddore.[18] The next was a raid on Canso in 1723.[19] Then in July 1724 a group of sixty Mikmaq and Maliseets raided Annapolis Royal.[20]

The treaty that ended the war marked a significant shift in European relations with the Mi'kmaq and Maliseet. For the first time a European Empire formally acknowledged that its dominion over Nova Scotia would have to be negotiated with the region's indigenous inhabitants. The treaty was invoked as recently as 1999 in the Donald Marshall case.[21]

King George's War

During King George's War (War of the Austrian Succession), a force of New England militia, under William Pepperell and Commodore Peter Warren of the Royal Navy, succeeded in capturing Louisbourg in 1745. Yet by the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle that ended the war in 1748, France got Louisbourg back by trading off other of its conquests in the Netherlands and India. The New Englanders were outraged, and as a counterweight to the continuing French strength at Louisbourg, the British founded the military settlement of Halifax in 1749, with a strong naval base in its spacious harbour.

During King George's War, military conflicts in Nova Scotia included: Raid on Canso; Siege of Annapolis Royal (1744); the Siege of Louisbourg (1745); the Duc d'Anville Expedition and the Battle of Grand Pré. Fortress Louisbourg was captured by American colonial forces in 1745, then returned by the British to France in 1748.

Father Le Loutre’s War

Father Le Loutre’s War (1749–1755), also known as the Indian War, the Micmac War and the Anglo-Micmac War,[22] happened between King George's War and the French and Indian War in Acadia and Nova Scotia.[23] The war was fought by the British and New Englanders, primarily under the leadership of New England Ranger John Gorham and British Officer Charles Lawrence. They fought against the Mi'kmaq and Acadians who were led by French priest Jean-Louis Le Loutre. The overall upheaval of the war was unprecedented. Atlantic Canada witnessed more population movements, more fortification construction, and more troop allocations than ever before in the region.[24]

During Father Le Loutre's War, the British attempted to firmly establish control of the major Acadian settlements in peninsular Nova Scotia and to extend British control to the disputed territory of present-day New Brunswick. The British also wanted to establish Protestant communities in Nova Scotia. During the war, the Acadians and Mi'kmaq also left Nova Scotia for the French colonies of Île Saint-Jean (Prince Edward Island) and Île Royale (Cape Breton Island). The French also tried to maintain the disputed territory of present-day New Brunswick. Throughout the war, the Mi’kmaq and Acadians attacked the British fortifications of Nova Scotia and the newly established Protestant settlements. They wanted to retard British settlement and buy time for France to implement its Acadian resettlement scheme.[25]

The war began with the British unilaterally establishing Halifax, which was a violation of an earlier treaty with the Mi'kmaq (1726), which was signed after Dummer's War. As a result, Acadians and Mi'kmaqs orchestrated attacks at Chignecto, Grand-Pré, Dartmouth, Canso, Halifax and Country Harbour. The French erected forts at present day Saint John, Chignecto and Port Elgin, New Brunswick. The British responded by attacking the Mi'kmaq and Acadians at Mirligueche (later known as Lunenburg), Chignecto and St. Croix. The British also unilaterally established communities in Lunenburg and Lawrencetown. Finally, the British erected forts in Acadian communities located at Windsor, Grand-Pré and Chignecto. The war ended after six years with the defeat of the Mi'kmaq, Acadians and French in the Battle of Fort Beauséjour.

Seven Years' War

Main article: French and Indian WarMaritime Theatre

Seven Years' War in

North America:

The French and Indian War,

Atlantic theaterAction of 8 June 1755 – Chignecto – Bay of Fundy – Petitcodiac – Lunenburg – Louisbourg (1757) – Bloody Creek – Louisbourg (1758) – Petitcodiac River – Ile Saint-Jean – Gulf of St. Lawrence – St. John River – Restigouche – St. John'sSt. John River Campaign: Raid on Grimrose (present day Gagetown, New Brunswick). This is the only contemporaneous image of the Expulsion of the Acadians

The fourth and final colonial war was the French and Indian War. In the maritime theatre of the conflict, military conflicts in Nova Scotia included: Battle of Fort Beauséjour; Bay of Fundy Campaign (1755); the Battle of Petitcodiac; the Raid on Lunenburg (1756); the Louisbourg Expedition (1757); Battle of Bloody Creek (1757); Siege of Louisbourg (1758), Petitcodiac River Campaign, Gulf of St. Lawrence Campaign (1758), St. John River Campaign, and Battle of Restigouche.

The British Conquest of Acadia happened in 1710. Over the next forty-five years the Acadians refused to sign an unconditional oath of allegiance to Britain. During this time period Acadians participated in various militia operations against the British and maintained vital supply lines to the French Fortress of Louisbourg and Fort Beausejour.[26]

During the French and Indian War, the British sought to neutralize any military threat Acadians posed and to interrupt the vital supply lines Acadians provided to Louisbourg by deporting Acadians from Acadia.[27]

The British began the Expulsion of the Acadians with the Bay of Fundy Campaign (1755). Over the next nine years over 12,000 Acadians were removed from Nova Scotia.[28]

St. Lawrence and Mohawk Theatre

Seven Years' War in

North America:

The French and Indian War,

St. Lawrence and Mohawk theaterLake George – Fort Bull – Fort Oswego – 1st Snowshoes – Sabbath Day Point – Fort William Henry – German Flatts – 2nd Snowshoes – Fort Carillon – Fort Frontenac – La Belle-Famille – Fort Niagara – Fort Ticonderoga – Beauport – Quebec – St. Francis – Sainte-Foy – Thousand IslandsIn the St. Lawrence and Mohawk theater of the conflict, the French had begun to challenge the claims of Anglo-American traders and land speculators for supremacy in the Ohio Country to the west of the Appalachian Mountains—land that was claimed by some of the British colonies in their royal charters. In 1753, the French started the military occupation of the Ohio Country by building a series of forts. In 1755, the British sent two regiments of the line to North America to drive the French from these forts, but these were destroyed by French Canadians and American Indians as they approached Fort Duquesne. War was formally declared in 1756, and in Canada, six French regiments of troupes de terre, or line infantry, came under the command of the newly arrived general, the 44-year-old Marquis de Montcalm. Accompanying him were another two battalions of 'troupes de terre', bringing the total number of French professional soldiers in the colony to about 4,000. This was the first significant aggregation of trained professional soldiers on what was to be Canadian soil.

The Death of General Wolfe, painted by Benjamin West, apocryphally depicts General Wolfe's final moments during the Battle of the Plains of Abraham in 1759.

The Death of General Wolfe, painted by Benjamin West, apocryphally depicts General Wolfe's final moments during the Battle of the Plains of Abraham in 1759.

Under their new commander, the French at first achieved a number of startling victories over the British, first at Fort William Henry to the south of Lake Champlain, where, in 1757, over 2,400 men, mostly British regulars, surrendered. In the following year, an even greater victory followed when the British army—numbering about 15,000 under Major General James Abercrombie—was roundly defeated in its attack on a French fortification at Carillon (later renamed Fort Ticonderoga by the British) at the southern tip of Lake Champlain. The French numbered no more than 3,500, but before the British withdrew, the French had inflicted a loss of about 2,000 men, mostly regulars, for a total French loss of about 350. In the meantime, the British war effort had been galvanized by the appointment of William Pitt as British Prime Minister, who was determined to win battles, and who decided that North America would be the crux of the British war effort. In June 1758, a British force of 13,000 regulars under Major General Jeffrey Amherst, with James Wolfe as one of his brigadiers, landed and permanently captured the Fortress of Louisbourg.

A year later Wolfe set his gaze on Quebec City. After several botched landing attempts including particularly bloody defeats at the Battle of Beauport and the Battle of Montmorency Camp, Wolfe succeeded in slipping his army ashore, forming ranks on the Plains of Abraham September 12. Montcalm, against the better judgment of his officers, sallied out with a numerically inferior force to meet the British. An epic battle followed in which Wolfe was killed, Montcalm mortally wounded, and 658 British and 644 French fell dead or wounded. Badly mauled by massed British volleys, the French retreated to the citadel and endured a painful siege and blockade before capitulating on September 18.

However, in the spring of 1760, the last French General, François Gaston de Lévis, marched back to Quebec from Montreal and defeated the British at the Battle of Sainte-Foy in a battle similar to that of the previous year; now the situation was reversed, with the French laying siege to the Quebec fortifications behind which the British retreated. However, the French finally had to concede the loss of New France when the Royal Navy rather than the French fleet sailed up the St Lawrence after the breakup of the winter ice. France lost almost all of its North American possessions, and retained only the small islands of Saint-Pierre et Miquelon as a base for its fishing fleet, which worked the Grand Banks. The French formally withdrew from much of North America in 1763 when they signed the Treaty of Paris. France was given the choice of keeping either New France or its sugar-producing Caribbean island colony Guadeloupe, and chose the latter as it had ten times the GDP of Canada.

American Revolution

St. Lawrence Theatre

With the French threat eliminated, Britain's eastern seaboard colonies became increasingly restive. The American Revolution largely arose from their resentment of paying taxes to support a large military establishment, when there was no obvious enemy. This was augmented by further suspicions of British motives when the Ohio Valley and other western territories previously claimed by France were not annexed to the existing British colonies, especially Pennsylvania and Virginia, which had long-standing claims to the region. Instead, under the Quebec Act, this territory was set aside for the First Nations. The American Revolutionary War (1776–83) saw the revolutionaries use force to break free from British rule and claim these western lands. American forces took Montreal and the chain of forts in the Richelieu Valley, but attempts by the revolutionaries to take Quebec City were repelled. During this time most French Canadians stayed neutral.

Maritime Theatre

Throughout the war, American privateers devastated the maritime economy by raiding many of the coastal communities. There were constant attacks by American privateers,[29] such as the Raid on Lunenburg (1782), numerous raids on Liverpool, Nova Scotia (October 1776, March 1777, September 1777, May 1778, September 1780) and a raid on Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia (1781).[30]

American Privateers also raided Canso, Nova Scotia (1775). In 1779, American privateers returned to Canso and destroyed the fisheries, which were worth £50,000 a year to Britain.[31]

To guard against such attacks, the 84th Regiment of Foot (Royal Highland Emigrants) was garrisoned at forts around the Atlantic Canada. Fort Edward (Nova Scotia) in Windsor, Nova Scotia was the Regiment's headquarters to prevent a possible American land assault on Halifax from the Bay of Fundy. There was an American attack on Nova Scotia by land, the Battle of Fort Cumberland followed by the Siege of Saint John (1777). There was also rebellion from those within Nova Scotia: the Maugerville Rebellion (1776) and the Battle at Miramichi (1779).

During the war, American Privateers captured 225 vessels either leaving or arriving at Nova Scotia ports.[32] In 1781, for example, as a result of the Franco-American alliance against Great Britain, there was also a naval engagement with a French fleet at Sydney, Nova Scotia, near Spanish River, Cape Breton.[33] The British also captured numerous American Privateers such as in the naval battle off Halifax. The Royal Navy also used Halifax as a base from which to launch attacks on New England, such as the Battle of Machias (1777).

Loyalists

The revolutionaries' failure to achieve success in these areas, and the continuing allegiance to Britain of some colonists, resulted in the split of Britain's North American empire. Many Americans who remained loyal to the Crown, known as the United Empire Loyalists, moved north, greatly expanding the English-speaking population. The independent republic of the United States emerged to the south, while a series of loyal British colonies remained in place along its northern border. The remaining British colonies were collectively referred to as British North America.

19th century

War of 1812

Main article: War of 1812Great Lakes Theatre

After the cessation of hostilities, animosity and suspicion continued between the United States and the United Kingdom. This erupted into a shooting war in 1812, when the Americans declared war on the British. Among the reasons for the war was British harassment of US ships on the high seas (including impressment of American seamen into the Royal Navy), the occurrence of which was a byproduct of British involvement in the ongoing Napoleonic Wars. The Americans did not possess a navy capable of challenging the Royal Navy, and so an invasion of Canada was proposed as the only feasible means of attacking the British Empire. Americans on the western frontier also hoped an invasion would bring an end to what they saw as British support of American Indian resistance to the westward expansion of the United States, and finalize their claim to the western territories. The early strategy was to temporarily seize Canada as a means of forcing concessions from the British. However, as the war progressed, outright annexation was more frequently cited as an objective—an early expression of what would later be called "Manifest Destiny". Many Americans hoped the French Canadians would welcome the chance to overthrow their British rulers.[34]

The Americans launched an invasion across the northern border in July 1812. The war raged back and forth along the border of Upper Canada, on land as well as on the waters of the Great Lakes. The British succeeded in capturing Detroit in July, and in October. On July 12, U.S. General William Hull invaded Canada at Sandwich (later known as Windsor). The invasion was quickly halted, and Hull withdrew, but this gave Brock the excuse he needed to abandon Prevost's orders. Securing Tecumseh's aid, Brock advanced on Detroit. At this point, even with his American Indian allies, Brock was outnumbered approximately two to one. However, Brock had gauged Hull as a timid man, and particularly as being afraid of Tecumseh's natives. Brock thus decided to use a series of tricks to intimidate Hull. Needless to say, the defeat of Detroit was utter and complete.

A major American thrust across the Niagara frontier was defeated at the Battle of Queenston Heights by a combined force of British regular troops and colonial militia under Sir Isaac Brock, who lost his life in the battle.

1813 was the year of American victories, when they retook Detroit and enjoyed a string of successes along the western end of Lake Erie, culminating in the Battle of Lake Erie (September 10) and the Battle of Moraviantown or Battle of the Thames on October 5. The naval battle secured U.S. dominance of lakes Erie and Huron. At Moraviantown, the British lost one of their key commanders, the Shawnee chief Tecumseh. Further east, the Americans succeeded in capturing and burning York (later Toronto) and taking Fort George at Niagara, which they held until the end of the year. However, in the same year, two American thrusts against Montreal were defeated—one by a force of British regulars at Crysler's Farm southwest of the city on the St Lawrence; the other, by a force of mostly French Canadian militia under the command of Charles de Salaberry, to the south of the city at Allan's Corners on the Chateauguay River. The Iroquois tribes of the Upper Canada, the Caughnawagas from near Montreal, and western tribes under the Shawnee chief, Tecumseh, were valued allies of the British throughout the campaign. These First Peoples played an important part in many battles and on many occasions had a psychologically debilitating impact on their enemy.

The British recaptured all of their lost territory and seized Michilimackinac in Michigan, and Fort Niagara in New York state, across from Fort George at the mouth of the Niagara River. The defeat of Napoleon in 1815 gave the British the chance to turn their attention to the North American theatre and launch raids on Washington, Baltimore and New Orleans. After the capture of Washington, DC in September at Bladensburg, the British troops burned down the White House and other government buildings, only to be repulsed as they moved north to advance on Baltimore while the forces attacking New Orleans were routed after suffering severe casualties.

In March 1815, the two opponents signed a peace treaty that restored the borders that had existed before the war. While thoroughly British, Sir Isaac Brock became a martyred Canadian hero. The successful defence of Canada relied on Canadian troops, British regular troops, the Royal Navy, and Native Indian allies. Neither side of the war can claim victory. [35]

Maritime Theatre

War of 1812, Halifax, NS: HMS Shannon leading the captured American Frigate USS Chesapeake into Halifax Harbour (1813)

War of 1812, Halifax, NS: HMS Shannon leading the captured American Frigate USS Chesapeake into Halifax Harbour (1813)

During the War of 1812, Nova Scotia’s contribution to the war effort was communities either purchasing or building various privateer ships to lay siege to American vessels.[36] Three members of the community of Lunenburg, Nova Scotia purchased a privateer schooner and named it Lunenburg on August 8, 1814.[37] The Nova Scotian privateer vessel captured seven American vessels. The Liverpool Packet from Liverpool, Nova Scotia was another Nova Scotia privateer vessel that caught over fifty ships in the war - the most of any privateer in Canada.

Perhaps the most dramatic moment in the war for Nova Scotia was HMS Shannon's leading the captured American frigate USS Chesapeake into Halifax Harbour (1813). Many of the prisoners were kept at Deadman's Island, Halifax.

British withdrawal

The fear that the Americans might reactivate their wish to conquer Canada remained a serious concern for at least the next half century, and was the chief reason for the retention of a large British garrison there. From the 1820s to the 1840s, there was extensive construction of fortifications in the colonies, as the British attempted to create strong points around which defending forces might centre in the event of an American invasion; these include the Citadels at Quebec City and Halifax, and Fort Henry in Kingston. The Rideau Canal was built during these years to allow ships in wartime to travel a more northerly route from Montreal to Kingston. (The customary peacetime route was the St Lawrence River, which constituted the northern edge of the American border, and hence was vulnerable to enemy attack and interference.)

British regulars struggle forward at the Battle of Saint-Denis, 1837.

British regulars struggle forward at the Battle of Saint-Denis, 1837.

One of the most important actions by the British forces during this period was the putting down of the Rebellions of 1837. The Upper Canada Rebellion was quickly and decisively defeated by the British forces. Attacks the next year by Hunters' Lodges, U.S. irregulars who expected to be paid in Canadian land, were crushed in 1838 in battles at Pelee Island and Prescott. The Lower Canada Rebellion was a greater threat to the British, and the rebels were victorious at the Battle of St. Denis on November 23. Two days later, the rebels were defeated at the Battle of Saint-Charles, and on December 14, they were finally routed at the Battle of Saint-Eustache.

By the 1850s, fears of an American invasion had begun to diminish, and the British felt able to start reducing the size of their garrison. The Reciprocity Treaty, negotiated between Canada and the United States in 1854, further helped to alleviate concerns. However, tensions picked up again during the American Civil War (1861–65), apparently reaching a peak with the Trent Affair of late 1861 and early 1862. This was touched off when the captain of a US gunboat stopped the Royal Mail Steamship Trent and removed two Confederate officials who were bound for Britain. The British government was outraged and, with war appearing imminent, took steps to reinforce its British North American garrison, which was increased from a strength of 4000 to 18,000. In the end, cooler heads prevailed, war was averted, and the sense of crisis subsided. This incident proved to be the final major episode of Anglo-American military confrontation in North America, as both sides increasingly became persuaded of the benefits of amicable relations. At the same time, many Canadians went south to fight in the Civil War, with most joining the Union army, although some Canadians, were sympathetic towards the Confederacy (see Canada and the American Civil War).

In the meantime, Britain was becoming concerned with military threats closer to home, and disgruntled at paying to maintain a garrison in colonies that were becoming increasingly self-assertive, and that, after 1867, were united in the self-governing Dominion of Canada. Consequently, in 1871, the troops of the British garrison were withdrawn from Canada completely, save for Halifax and Esquimalt, where British garrisons remained in place purely for reasons of imperial strategy.

Fenian raids

Main article: Fenian raids The Battle of Ridgeway, 1866.

The Battle of Ridgeway, 1866.

Canadian Home-Guard defending against Fenians in 1870.

Canadian Home-Guard defending against Fenians in 1870.

It was during this period of re-examination of the British military presence in Canada and its ultimate withdrawal that the last invasion of Canada occurred. It was not carried out by any official US government force, but by an organization called the Fenians. This was a group of Irish Americans, mostly Union Army veterans from the Civil War who believed that by seizing Canada, concessions could be wrung from the British government regarding their policy in Ireland.[38] The Fenians had also, to a large degree, incorrectly estimated that Irish Canadians, who were quite numerous in Canada, would support their invasive efforts and rise up, both politically and militarily. Most Irish settlers in Upper Canada at that time were Protestant, and for the most part loyal to the British Crown.

After the events of the Civil War, anti-British sentiment was high in the United States. British-built Confederate warships had wreaked havoc on US commerce during the war. Irish-Americans were a large and politically important constituency, particularly in parts of the Northeastern States and large regiments of Irish Americans had participated in the war. Thus, while deeply concerned about the Fenians, the US government, led by Secretary of State William H. Seward,[39] generally ignored the Fenian organizing efforts. The Fenians were allowed to openly organize and arm themselves, and were even allowed to recruit in Union Army camps.[40] The Americans were not prepared to risk war with Britain, and intervened when the Fenians threatened to endanger American neutrality.

The Fenians were a serious threat to Canada, being veterans of the Union Army they were well armed. They made three attacks in 1866: one on Campobello Island in New Brunswick in April, and the others in the Niagara and the St Lawrence Valley regions in July. The Campobello and St. Lawrence valley attacks failed. The Fenians won the Battle of Ridgeway when troops, mostly University of Toronto students and young men from Hamilton, were led into a bungled attack and a sloppy retreat, but the Fenians quickly withdrew, fearing a British counter-attack. In New Brunswick, their failure was due to the presence of a strong force of British regulars and the confiscation of Fenian weapons by the American navy. Two later attacks along the Quebec-Vermont frontier in 1870 and Manitoba in 1871 proved similarly fruitless.

Despite these failures, the raids had some impact on Canadian politicians who were then locked in negotiations leading up to the Confederation agreement of 1867. The raids reinforced a sense of military vulnerability, especially because the British were known to be seriously considering the downsizing of their garrison, if not its outright withdrawal. The Confederation debates were to some degree held in an atmosphere of military crisis, and the greater military security that would be gained through the pooling of colonial resources was one of the factors that weighed heavily in Confederation's favour.[41]

Canadian militia

See also: Wolseley ExpeditionWith Confederation in place and the British garrison gone, Canada assumed full responsibility for its own defence; it passed the Militia Act in 1868 and Britain undertook to send aid in the event of a serious emergency, and the Royal Navy continued to provide maritime defence. Small professional batteries of artillery were established at Quebec City and Kingston. In 1883, a third battery of artillery was added, and small professional schools of cavalry and infantry were created. These were intended to provide professional backbone for the much larger force of militia that was to form the bulk of the Canadian defence effort. In theory, every able-bodied man between the ages of 18 and 60 was liable to be conscripted for service, but in practice, the defence of the country rested on the services of volunteers who made up the so-called Active Militia, which in 1869 numbered 31,170 officers and men. During the remaining decades of the century, this force was consolidated, attending summer camps, parading about in colourful uniforms, and occasionally being mustered to serve in times of strikes and other civil emergencies.

Contemporary lithograph of the Battle of Fish Creek.

Contemporary lithograph of the Battle of Fish Creek.

The most important early tests of the militia were the expeditions against the rebel forces of Louis Riel in the Canadian west. The Wolseley Expedition, containing a mix of British and militia forces, restored order after the Red River Rebellion with little violence in 1870. A greater test was the North-West Rebellion in 1885 that saw the largest military effort undertaken on Canadian soil since the end of the War of 1812. The Rebellion saw a series of battles between the Métis and their First Nations allies on one side against the Militia and North-West Mounted Police on the other. The government forces ultimately emerged victorious despite having suffered a number of early defeats and reversals at the Battle of Duck Lake, the Battle of Fish Creek and the Battle of Cut Knife Hill.

Outnumbered and out of ammunition, the Métis portion of the North-West Rebellion collapsed with the siege and Battle of Batoche. The Battle of Loon Lake, which ended this conflict, is notable as the last battle to have been fought on Canadian soil. Government losses during the North-West Rebellion amounted to 58 killed and 93 wounded.

In 1884, Britain for the first time asked Canada for aid in defending the empire. The mother country asked Canada to send experienced boatmen to the Sudan to help rescue Major-General Charles Gordon from the Mahdi uprising. However, Ottawa was reluctant to do this, and eventually Governor General Lord Lansdowne recruited a private force of 386 Voyageurs who were placed under the command of Canadian Militia officers. This force, known as the Nile Voyageurs, served ably in the Sudan and became the first Canadian force to serve abroad.[42] 16 voyageurs died during the campaign.

Twentieth century

Boer War

The South African War Memorial commemorates Canada's participation in the Boer War

The South African War Memorial commemorates Canada's participation in the Boer War Main article: Second Boer War#Canada

Main article: Second Boer War#CanadaThe military business of the empire was again an issue when Britain found itself hard pressed in the Second Boer War in South Africa. The British asked for Canadian help in the conflict, and the Conservative Party was adamantly in favour of raising divisions for service in South Africa. English-Canadian opinion was overwhelmingly in favour of active Canadian participation in the war. French Canadians almost universally opposed the war, as did several other groups. This split the governing Liberal Party deeply, as it relied on both pro-imperial Anglo-Canadians and anti-imperial Franco-Canadians for support. Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier initially sent 1,000 soldiers of the 2nd (Special Service) Battalion of the Royal Canadian Regiment of Infantry. Later, other contingents were sent, including the privately raised Strathcona's Horse.

The Canadian forces missed the early period of the war and the great British defeats of Black Week. The Canadians in South Africa won much acclaim for leading the charge at the Second Battle of Paardeberg, one of the first decisive victories of the war. At the Battle of Leliefontein on November 7, 1900, three Canadians, Lieutenant Turner, Lieutenant Cockburn, Sergeant Holland and Arthur Richardson of the Royal Canadian Dragoons were awarded the Victoria Cross for protecting the rear of a retreating force.[43] Ultimately, over 8,600 Canadians volunteered to fight in the South African War.[44] Lieutenant Harold Lothrop Borden, however, became the most famous Canadian casualty of the Second Boer War.[45]

About 7,400 Canadians, including 12 female nurses, served in South Africa. Of these, 224 died, 252 were wounded, and several were decorated with the Victoria Cross. The war remained deeply unpopular in Quebec, where many people viewed it as the crushing of a democratic minority group by an imperial power, which in many ways, was similar to the French-Canadian experience during the Lower Canada Rebellion of 1837 to 1838. Canadian forces also participated in the British-led concentration camp programs that resulted in the deaths of thousands of Boer civilians.[46]

Main article: Royal Canadian Navy HMCS Rainbow in 1910.

HMCS Rainbow in 1910.

Soon after the debate over the Second Boer War, a similar one developed over whether or not Canada should have its own navy. Canada had long had a small fishing protection force attached to the Department of Marine and Fisheries, but relied on Britain for maritime protection. Britain was increasingly engaged in an arms race with Germany, and in 1908, asked the colonies for help with the navy. The Conservative Party of Canada argued that Canada should merely contribute money to the purchase and upkeep of some British Royal Navy vessels. Some French-Canadian nationalists felt that no aid should be sent; others advocated an independent Canadian navy that could aid the British in times of need.

Eventually, Prime Minister Laurier decided to follow this compromise position, and the Canadian Naval Service was created in 1910 and designated as the Royal Canadian Navy in August 1911. To appease imperialists, the Naval Service Act included a provision that in case of emergency, the fleet could be turned over to the British. This provision led to the strenuous opposition to the bill by Quebec nationalist Henri Bourassa. The bill set a goal of building a navy composed of five cruisers and six destroyers. The first two ships were Niobe and Rainbow, somewhat aged and outdated vessels purchased from the British. With the election of the Conservatives in 1911, in part because the Liberals had lost support in Quebec, the navy was starved for funds, but during the First World War, it was greatly expanded and played an important role in both the Atlantic and Pacific.

Creation of a Canadian army

Main article: History of the Canadian ArmyAs British troops began to leave Canada in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the importance of the Militia (comprising various cavalry, artillery, infantry and engineer units) grew. The last Officer Commanding the Forces (Canada), Lord Dundonald, instituted a series of reforms in which Canada gained its own technical and support branches. These various services, called "corps", included

- Canadian Engineer Corps (created July 1, 1903)

- Signalling Corps (created October 24, 1903)

- Canadian Army Service Corps December 1, 1903

- Permanent Active Militia Army Medical Corps July 2, 1904

- Ordinance Stores Corps July 1, 1903

- Corps of Guides 1902

In 1904, the appointment of Officer Commanding the Forces was replaced with a Canadian Chief of the General Staff. Additional corps would be created in the years before the First World War, including the world's first separate military dental corps.[47]

Creation of a Canadian air force

Main article: Royal Canadian Air Force Sopwith Dolphins of No.1 (Fighter) Squadron, CAF

Sopwith Dolphins of No.1 (Fighter) Squadron, CAF

The First World War was the catalyst for the formation of Canada's air force. At the outbreak of war, there was no independent Canadian air force, although many Canadians flew with the Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Naval Air Service.

In 1914 the Canadian government authorized the formation of the Canadian Aviation Corps. The corps was formed to accompany the Canadian Expeditionary Force to Europe and consisted of one aircraft, a Burgess-Dunne, that was never used. The Canadian Aviation Corps was disbanded in 1915. A second attempt at forming a truly Canadian air force was made in 1918 when two Canadian squadrons (one bomber and one fighter) were formed by the British Air Ministry in Europe. The Canadian government took control of the two squadrons in 1918 by forming the Canadian Air Force. This air force, however, never saw service and was disbanded in 1920.

The British government encouraged Canada to institute a peacetime air force by giving Canada several surplus aircraft, and in 1920 a new Canadian Air Force (CAF) directed by the Air Board was formed as a part-time or militia service providing flying refresher training. After a reorganization the CAF became responsible for all flying operations in Canada, including civil aviation. Air Board and CAF civil flying responsibilities would be handled by the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) after its creation in April 1924.The Second World War would see the RCAF become a truly military service.

First World War

Further information: Canada in the World Wars and Interwar YearsMain article: Military history of Canada during World War IOn August 4, 1914, Britain entered the First World War by declaring war on Germany. The British declaration of war automatically brought Canada into the war, because of Canada's legal status as subservient to Britain. However, the Canadian government had the freedom to determine the country's level of involvement in the war. The Militia was not mobilized and instead an independent Canadian Expeditionary Force was raised.

The Canadian Corps was formed from the Canadian Expeditionary Force in September 1915 after the arrival of the 2nd Canadian Division in France. The Corps was expanded by the addition of the 3rd Canadian Division in December 1915 and the 4th Canadian Division in August 1916. The organization of a 5th Canadian Division began in February 1917, but it was still not fully formed when it was broken up in February 1918 and its men used to reinforce the other four divisions. Although the Corps was within and under the command of the British Army, there was considerable pressure among Canadian leaders, especially following the Battle of the Somme, for the Corps to fight as a single unit rather than spreading the divisions through the whole army. Plans for a second Canadian corps and two additional divisions were scrapped, and a divisive national dialogue on conscription for overseas service was begun.[48]

The other major combatants had all introduced conscription to replace the massive casualties they were suffering. Spearheaded by Sir Robert Borden who wished to maintain the continuity of Canada's military contribution and with a burgeoning pressure to introduce and enforce conscription, the Military Service Act was ratified. Although reaction to conscription was favourable in English Canada the idea was deeply unpopular in Quebec. In the end, conscription raised about 120,000 soldiers, of whom about 47,000 actually went overseas. The Conscription Crisis of 1917 did much to highlight the divisions between French and English-speaking Canadians in Canada. Despite the rancour, the Conscription Crisis did not hinder Prime Minister Robert Borden's political career. In the In the Canadian Federal Election of 1917 the Union government won 153 seats, nearly all from English Canada. The Liberals won 82 seats. Although the Union government won a large majority of seats, the Union government won only 3 seats in Quebec., Borden's Union government won 153 seats, nearly all from English Canada. However, of Quebec's 65 seats, Borden's government won only 3.

In the later stages of the war, the Canadian Corps were among the most effective and respected of the military formations on the Western Front.[49] In 1919, Canada sent an expeditionary force to Siberia to aid the White Russians in the Russian Civil War. The vast majority of these troops were based in Vladivostok and saw little combat before they withdrew, along with other foreign forces.[50]

For a nation of eight million people, Canada's war effort was widely regarded as remarkable. A total of 619,636 men and women served in the Canadian forces in the First World War, and of these 66,655 were killed and another 172,950 were wounded. Canadian sacrifices are commemorated at eight memorials in France and Belgium. Two of the eight are unique in design: the giant white Vimy Memorial and the distinctive Brooding Soldier at the Saint Julien Memorial. The other six follow a standard pattern of granite monuments surrounded by a circular path. They are the Hill 62 Memorial and Passchendaele Memorial in Belgium, and the Bourlon Wood Memorial, Courcelette Memorial, Dury Memorial, and Le Quesnel Memorial in France. There are also separate war memorials to commemorate the actions of the soldiers of Newfoundland in the Great War. The largest are the Beaumont-Hamel Newfoundland Memorial and the National War Memorial in St. John's. Newfoundland did not join Confederation until 1949.

Second World War

Main article: Military history of Canada during World War II Canadian forces in Italy advancing from the Gustav Line to the Hitler Line.

Canadian forces in Italy advancing from the Gustav Line to the Hitler Line.

Following the German invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939, Canada's Parliament supported the government's decision to declare war on Germany on September 10, one week after the United Kingdom and France. Canadian airmen played a small but significant role in the Battle of Britain, the Royal Canadian Navy and the Canadian merchant marine played a crucial role in the Battle of the Atlantic. C Force, two Canadian infantry battalions[51] were involved in the failed defence of Hong Kong. Troops of the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division also played a leading role in the disastrous Dieppe Raid in August 1942. The 1st Canadian Infantry Division and tanks of the independent 1st Canadian Armoured Brigade landed on Sicily in July 1943 and after a 38-day campaign there, took part in the successful Allied invasion of Italy. Canadian forces played an important role in the long advance north through Italy, eventually coming under their own corps headquarters after 5th Canadian Armoured Division joined them on the line in early 1944 after the costly battles on the Moro River and at Ortona.

On June 6, 1944, the 3rd Canadian Division (supported by tanks of the independent 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade) landed on Juno Beach in the Battle of Normandy. Canadian airborne troops had also landed earlier in the day behind the beaches. Resistance on Juno was fierce, and casualties were high in the assault waves, in particular the first assault waves, which sustained a 50 percent casualty rate. By day's end, however, the Canadians had made the deepest penetrations inland of any of the five seaborne invasion forces. The Canadians went on to play an important role in the subsequent fighting in Normandy, with the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division coming ashore in July and the 4th Canadian Armoured Division in August. In the meantime, both a corps headquarters (II Canadian Corps) and eventually an army headquarters—for the first time in Canadian military history—were activated. One of the most important Canadian contributions to the war effort was in the Battle of the Scheldt, where First Canadian Army defeated an entrenched German force at great cost to help open Antwerp to Allied shipping.

First Canadian Army fought in two more large campaigns; the Rhineland in February and March 1945, clearing a path to the Rhine River in anticipation of the assault crossing of that obstacle, and the subsequent battles on the far side of the Rhine in the last weeks of the war. The I Canadian Corps returned to northwest Europe from Italy in early 1945, and as part of a reunited First Canadian Army assisted in the liberation of The Netherlands (including the rescue of many Dutch from near-starvation conditions) and the invasion of Germany.

The Royal Canadian Air Force had three key responsibilities during the war: the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP), Canada's contribution to training military aviators; the Home War Establishment (HWE), which provide 37 squadrons for coastal defence, protection of shipping, air defence and other duties in Canada, and the Overseas War Establishment (OWE), which provided 48 squadrons serving with the Royal Air Force (RAF) in Europe, the Mediterranean and the Far East.

RCAF airmen served with RAF fighter and bomber squadrons, and played key roles in the Battle of Britain, antisubmarine warfare during the Battle of the Atlantic, and the bombing campaigns against Germany. Even though many RCAF personnel served with the RAF, No. 6 Group RAF Bomber Command was formed entirely of RCAF squadrons. Canadian air force personnel also provided close support of Allied forces during the Battle of Normandy and subsequent land campaigns in Europe. To free up male RCAF personnel who were needed on active operational or BCATP training duties, the RCAF Women's Division was formed in 1941. By the end of the war, the RCAF would be the fourth largest allied air force.[52]

Of a population approximately 11.5 million, 1.1 million Canadians served in the armed forces in the Second World War. Of these, an officially recorded total of 42,042 members of the armed forces gave their lives, and another 55,000 were wounded. Many others shared the suffering and hardship of war.[53] In line with other Commonwealth countries, a women's corps entitled the Canadian Women's Army Corps, similar to the RCAF Women's Division, was established to release men for front-line duties. The corps existed from 1941 to 1946, was re-raised in 1948 and finally disbanded in 1964.

Multilateralism, peacekeeping and the Cold War years

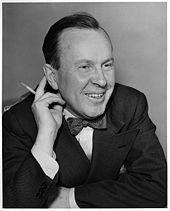

Further information: Canada in the Cold War Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson, considered a founder of modern peacekeeping for his efforts in resolving the Suez Crisis in 1956.

Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson, considered a founder of modern peacekeeping for his efforts in resolving the Suez Crisis in 1956.

Soon after the end of the Second World War, the Cold War began. As a founding member of NATO and a signatory to the NORAD treaty with the US, Canada committed itself to the alliance against the Communist bloc. Canadian troops were stationed in Germany throughout the Cold War, and Canada joined with the Americans to erect defences against Soviet attack, such as the DEW Line. As a middle power, Canadian policy makers realized that Canada could do little militarily on its own, and thus a policy of multilateralism was adopted whereby Canada would only join military efforts as part of a large coalition. Canada also chose to stay out of several wars, despite the participation of close allies, most notably the Vietnam War and the Second Iraq War, although Canada lent indirect support and Canadian citizens served in foreign armies in both conflicts. The postwar period saw a major reorganization when, in 1968, the three forces were merged into the Canadian Armed Forces, later renamed the Canadian Forces.

Canada in Korea

After the Second World War, Canada rapidly demobilized. When the Korean War broke out, Canada needed several months to bring its military forces up to strength, and eventually formed part of British Commonwealth Forces Korea. Canadian land forces thus missed most of the early back-and-forth campaigns because they did not arrive until 1951, when the attrition phase of the war had largely started. Canadian troops fought as part of the 1st Commonwealth Division, and distinguished themselves at the Battle of Kapyong and in other land engagements. HMCS Haida and other ships of the Royal Canadian Navy were in active service in the Korean War. Although the Royal Canadian Air force did not have a combat role in Korea, twenty-two RCAF fighter pilots flew on exchange duty with the USAF in Korea.[54] The RCAF was also involved with the transportation of personnel and supplies in support of the Korean War.

Canada sent 26,791 troops to fight in Korea. There were 1,558 Canadian casualties, including 516 dead. Korea has often been described as "The Forgotten War", because for most Canadians it is overshadowed by the Canadian contributions to the two world wars. Canada is a signatory to the original 1953 armistice, but did not keep a garrison in South Korea after 1955.[55]

Canada and the Vietnam War

Further information: Canada and the Vietnam WarCanada did not fight in the Vietnam War and diplomatically it was "officially non-belligerent".[56] The country's troop deployments to Vietnam were limited to a small number of national forces in 1973 to help enforce the Paris Peace Accords.[57] Nevertheless, the war had considerable effects on Canada, while Canada and Canadians affected the war, in return. In counter-current to the movement American draft-dodgers and deserters to Canada, about 30,000 Canadians volunteered to fight in southeast Asia.[58] Among the volunteers were fifty Mohawks from the Kahnawake reserve near Montreal.[59] One-hundred ten (110) Canadians died in Vietnam, and seven remain listed as Missing in Action.

Peacekeeping

Further information: List of Canadian Peacekeeping Missions Quote from Pearson on starting a UN peace force on the Peacekeeping Monument in Ottawa.

Quote from Pearson on starting a UN peace force on the Peacekeeping Monument in Ottawa.

Closely related to Canada's commitment to multilateralism has been its strong support for peacekeeping efforts. Canadian Nobel Peace Prize laureate Lester B. Pearson is considered to be the father of modern United Nations Peacekeeping, and Canada has a long history of participation in these missions. Pearson’s role in the creation of modern peacekeeping is a very convoluted one. Pearson had become a very prominent figure in the United Nations during its infancy, and found himself in a very peculiar position in 1956 during the Suez canal crisisSuez Crisis. Pearson and Canada found themselves stuck between a conflict of their closest allies, being looked upon to find a solution. Britain and France had broken International laws in the taking of the canal and were being denounced by the United States.[60] During United NationsUnited Nations meetings Lester B. Pearson proposed to the security council that a United Nations police force be established to prevent further conflict in the region, while the countries involved are able to sort out a resolution.[61] Pearson’s proposal and offer to actually dedicate 1,000 Canadian soldiers, is seen as a brilliant political move that saved the world from another war.[62] Canada participated in every UN peacekeeping effort from their beginning until 1989, and has since then continued to play a significant role.[63] More than 125,000 Canadians have served in some 50 UN peacekeeping missions since 1949, with 116 deaths.

Since 1995, however, Canadian direct participation in UN peacekeeping efforts has greatly declined. In July 2006, for instance, Canada ranked 51st on the list of UN peacekeepers, contributing 130 peacekeepers out of a total UN deployment of over 70,000.[64] That number decreased largely because Canada began to direct its participation to UN-sanctioned military operations through NATO, rather than directly to the UN. The number of Canadian soldiers on UN-sanctioned operations in July 2006 was 2,859.[65]

The first Canadian peacekeeping mission, even before the creation of the formal UN system, was a 1948 mission to Kashmir. Other important missions include the long stay in Cyprus, observation missions in the Sinai and Golan Heights, and the NATO mission in Bosnia. The 1993 Canadian response to Operation Medak pocket in Bosnia was the largest battle fought by Canadian forces since the Korean War.[66] One of the darkest moments in recent Canadian military history occurred during the humanitarian mission to Somalia in 1993, when Canadian soldiers tortured a Somali teenager to death, leading to the Somalia Affair. Following an inquiry, the elite Canadian Airborne Regiment was disbanded and the reputation of the Canadian Forces suffered within Canada.[67] The loss of nine Canadian peacekeepers when their plane was shot down over Syria in 1974 remains the largest loss of life in a single event in Canadian peacekeeping history.

Significance of Canada’s Role in Peacekeeping

Canada’s role in the development and participation in Peacekeeping during the 20th and 21st centuries has played a major role in turning Canada into a prominent nation throughout the world.[68] Prior to Canada’s role in the Suez Canal Crisis, Canada was viewed by many as insignificant in issues of the world’s traditional powers. Canada’s successful role in the conflict gave Canada credibility and established it as a nation fighting for the common good of all the world’s nations and not just their allies.[69] Even to do this day Canada holds a certain prestige throughout the world.

Canadian Forces in Europe

Canada maintained a mechanized infantry brigade in West Germany from the 1950s (originally the 27th Canadian Infantry Brigade, later named 4 Combat Group and 4 Canadian Mechanized Brigade) to the 1990s as part of Canada's NATO commitments. This brigade was maintained at close to full strength and was equipped with Canada's most advanced vehicles and weapons systems as it was anticipated the brigade might have to move quickly in the event of a Warsaw Pact invasion of the west. The brigade was augmented by Militia soldiers from Canada and for a time even Royal Canadian Army Cadets were permitted to serve in the brigade for short periods.[70]

The Royal Canadian Air Force established No. 1 Air Division in the early 1950s to meet Canada's NATO air defence commitments in Europe. It consisted of twelve fighter squadrons located in four wings, two of which were in France, and two in West Germany.

Unification and the post–Cold War era

Unification

Main article: Unification of the Canadian ForcesIn 1964 the Canadian government decided to merge the Royal Canadian Air Force, the Royal Canadian Navy and the Canadian Army to form the unified Canadian Armed Forces. The aim of the merger was to reduce costs and increase operating efficiency.[71] The Minister of National Defence, Paul Hellyer stated on November 4, 1966, that "the amalgamation...will provide the flexibility to enable Canada to meet in the most effective manner the military requirements of the future. It will also establish Canada as an unquestionable leader in the field of military organization."[72] On February 1, 1968, unification was completed.

Gulf War

A Canadian CF-18 Hornet in Cold Lake, Alberta. CF-18s have supported NORAD air sovereignty patrols and participated in combat during the Gulf War and the Kosovo and Bosnia crisis.

A Canadian CF-18 Hornet in Cold Lake, Alberta. CF-18s have supported NORAD air sovereignty patrols and participated in combat during the Gulf War and the Kosovo and Bosnia crisis.

The 1991 Gulf War was a conflict between Iraq and a coalition force of 34 nations, led by the US. The result was a decisive victory of the coalition forces. Canada was one of the first nations to agree to condemn Iraq's 1990 invasion of Kuwait, and promptly agreed to join the US-led coalition.

In August, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney sent the destroyers HMCS Terra Nova, HMCS Athabaskan, and HMCS Huron to enforce the trade blockade against Iraq. The supply ship HMCS Protecteur was sent to aid the gathering coalition forces. While all others returned to Canada in the spring of 1992, HMCS Huron remained on station to enforce sanctions and was the first warship to enter Kuwait Harbour following the war. When the UN authorized full use of force in the operation, Canada sent a CF-18 squadron with support personnel. The nation sent a field hospital to deal with casualties from the ground war.

When the air war began, Canada's planes were integrated into the coalition force and provided air cover and attacked ground and naval targets. This was the first time since the Korean War that its forces had participated in combat operations. Canada suffered no casualties during the conflict, but since its end, many veterans have complained of suffering from Gulf War Syndrome.

A Canadian combat engineer regiment was investigated following the release of 1991 photographs which showed members posing with the dismembered bodies in a Kuwaiti minefield.[73]

Peacekeeping in Croatia

Canada's forces were part of UNPROFOR, UN peacekeeping force in Croatia and in Bosnia and Herzegovina during the Yugoslav wars in the 1990s.

The Canadian government claims that Canadian forces within the UN contingent clashed with the Croatian Army in what has been called Operation Medak Pocket, where 27 Croatian soldiers are reported to have been killed.[74] The battle at the Medak Pocket was called "the greatest battle of the Canadian Army since the Korean War",[75] and in 2002, the 2nd Battalion Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry Battle Group were awarded the Commander-in-Chief Unit Commendation "for a heroic and professional mission during the Medak Pocket Operation".[76] But according to some sources, this battle never happened. Former UNPROFOR Canadian officer, John John McGuinnes, a witness at the Norac-Ademi trial for war crimes in Medak Pocket, stated that there were one or two shootouts, but there were no injuries. He also said that the decorations were awarded for whole tour in Croatia, not only for participation in Medak pocket activity.[77]

Kosovo War - Operation Allied Force

The NATO Bombing of Yugoslavia (NATO code-name Operation Allied Force or, by the United States, Operation Noble Anvil) was NATO's first combat action in its 45 year history. This war was fought against a seasoned Serbian Military in a Joint Operating Area that encompassed the entire Former Republic of Yugoslavia. Serbian forces possessed a lethal Integrated Air Defense System that presented a formidable threat to all Coalition fighters. Although Air Superiority was never fully achieved, temporary and localized air superiority for Strike packages was gained through massive employments of USAF HARM (High-speed Anti Radiation Missile) and RAF ALARM (Royal Air Force Air Launched Anti Radiation Missile) pre-emptive strikes. The Serbian Army had massed along the Kosovo-Albanian-Macedonian border in anticipation of NATO land forces moving north. The Canadian Air Force deployed a total of 18 CF-18s, enabling them to conduct 24/7 operations and deliver 10% of all bombs dropped during the war. Canadian Fighter pilots successfully attacked the full spectrum of targets from fielded FRY forces on the Kosovar-Albanian border to MIG29 airfields north of Belgrade. Although the strikes lasted from March 24, 1999, to June 11, 1999, all deployed personnel and aircraft were able to safely return. This combat action resulted in the production of a new medal called the General Campaign Star (GCS)and General Campaign Medal (GCM). In 2009, 441 Tactical Fighter Squadron and 425 Tactical Fighter Squadron were awarded the Battle Honour "KOSOVO" for this campaign. These battle honours were the first to be awarded to a Canadian unit since the Korean War.

War in Afghanistan

Main article: Canada's role in the invasion of AfghanistanCanada joined a U.S.-led coalition in the 2001 Attack on Afghanistan. The war was a response to the September 11, 2001, Terrorist Attacks, with the goal to defeat the Taliban government and rout Al-Qaeda. Canada sent special forces and ground troops to the conflict. In this war, a Canadian sniper set the world record for longest distance kill. In early 2003, Canadian JTF2 troops were photographed taking Afghan prisoners, sparking a debate of the Geneva Conventions.[78] After the war, Canada formed an important part of the NATO-led stabilization force, ISAF. In November 2005, Canadian military participation shifted from ISAF in Kabul to Operation Archer, a part of Operation Enduring Freedom in and around Khandahar. As of December 18, 2010, 154 Canadian soldiers had been killed in the Afghanistan mission[79] (see also: Canadian Forces casualties in Afghanistan).

On May 17, 2006, Captain Nichola Goddard of the Royal Canadian Horse Artillery became Canada's first female combat arms casualty. One of the most notable battles that the Canadian Forces have fought in Afghanistan thus far is the Canadian-led Operation Medusa in which the second battle of Panjwaii was fought. Canada was also the main allied combatant in the first but less intense battle of Panjwaii.[80]

Canadian troops have taken on an extended role in combat operations in southern Afghanistan, meeting Taliban forces in open conflict. The Canadian mission to Afghanistan is scheduled to end in February 2011, but there is divisive debate in Canada as to whether the mission should be extended.

Invasion of Iraq (2003)

Main article: Canada and the Iraq WarIn 2003, under Prime Minister Jean Chrétien, about a hundred Canadian soldiers, on exchange to American units, participated in the 2003 invasion of Iraq.[81] Nevertheless, Canada chose not to "join with the so-called Coalition of the willing"[81] during the invasion of Iraq.[81] Canada refused to do so unless it was approved by the United Nations. This decision, popular in most of Canada,[82] upset the administration of American president George W. Bush.

Concurrently, Canada deployed some additional troops to the War on Terrorism in Afghanistan. Some claim that it incidentally freed up some American and British troops for assignment in Iraq. Canada continues to have warships in the Persian Gulf area as part of Operation Altair. Their presence is justified by Canada's commitment to Operation Enduring Freedom.[83]

On October 9, 2008, the CBC published this statement:[81]

"in their book, The Unexpected War,[84] University of Toronto professor Janice Gross Stein and public policy consultant Eugene Lang write that the Liberal government would actually boast of that contribution to Washington. "In an almost schizophrenic way, the government bragged publicly about its decision to stand aside from the war in Iraq because it violated core principles of multilateral-ism and support for the United Nations. At the same time, senior Canadian officials, military officers and politicians were currying favour in Washington, privately telling anyone in the State Department or the Pentagon who would listen that, by some measures, Canada's indirect contribution to the American war effort in Iraq — three ships and 100 exchange officers — exceeded that of all but three other countries that were formally part of the coalition.""[81][84]