- History of Canada

-

History of Canada

This article is part of a series Timeline Pre-colonization

1534–1763

1764–1866

1867–1914

1914–1945

1945–1960

1960–1981

1982–1992

1992–presentTopics Constitutional history

Cultural history

Economic history

Former colonies & territories

Immigration history

Military history

Monarchical history

National sites

Persons of significance

Territorial evolution

BibliographyHistory of Canada portal The history of Canada covers the period from the arrival of Paleo-Indians thousands of years ago to the present day. Canada has been inhabited for millennia by distinctive groups of Aboriginal peoples, among whom evolved trade networks, spiritual beliefs, and social hierarchies. Some of these civilizations had long faded by the time of the first European arrivals and have been discovered through archaeological investigations. Various treaties and laws have been enacted between European settlers and the Aboriginal populations.

Beginning in the late 15th century, French and British expeditions explored, and later settled, along the Atlantic coast. France ceded nearly all of its colonies in North America to Britain in 1763 after the Seven Years' War. In 1867, with the union of three British North American colonies through Confederation, Canada was formed as a federal dominion of four provinces. This began an accretion of provinces and territories and a process of increasing autonomy from the British Empire, which became official with the Statute of Westminster of 1931 and completed in the Canada Act of 1982, which severed the vestiges of legal dependence on the British parliament.

Over centuries, elements of Aboriginal, French, British and more recent immigrant customs have combined to form a Canadian culture. Canada has also been strongly influenced by that of its linguistic, geographic and economic neighbour, the United States. Since the conclusion of the Second World War, Canadians have supported multilateralism abroad and socioeconomic development domestically. Canada currently consists of ten provinces and three territories and is governed as a parliamentary democracy and a constitutional monarchy with Queen Elizabeth II as its head of state.

Pre-colonization

Main article: Pre-colonization history of CanadaFurther information: Timeline of Canadian historyPaleo-Indians and Archaic periods

According to North American archeological and Aboriginal genetic evidence, North and South America were the last continents in the world with human habitation.[1][2] During the Wisconsin glaciation, 50,000 – 17,000 years ago, falling sea levels allowed people to move across the Bering land bridge (Beringia) that joined Siberia to north west North America (Alaska).[3][4] At that point, they were blocked by the Laurentide ice sheet that covered most of Canada, which confined them to Alaska for thousands of years.[5]

Around 16,000 years ago, the glaciers began melting, allowing people to move south and east into Canada.[6] The exact dates and routes of the peopling of the Americas are the subject of an ongoing debate.[2][7][8][9] The Queen Charlotte Islands, Old Crow Flats, and Bluefish Caves are some of the earliest archaeological sites of Paleo-Indians in Canada.[10][11][12] Ice Age hunter-gatherers left lithic flake fluted stone tools and the remains of large butchered mammals.

The North American climate stabilized around 8000 before the Common Era (BCE), 10,000 years ago. Climatic conditions were similar to modern patterns; however, the receding glacial ice sheets still covered large portions of the land, creating lakes of meltwater.[13][14] Most population groups during the Archaic periods were still highly mobile hunter-gatherers.[15] However, individual groups started to focus on resources available to them locally; thus with the passage of time there is a pattern of increasing regional generalization (i.e.: Paleo-Arctic, Plano and Maritime Archaic traditions).[15]

Post-Archaic periods

Great Lakes area of the Hopewell Interaction Area

PP=Point Peninsula Complex S=Saugeen Complex L=Laurel ComplexThe Woodland cultural period dates from about 2,000 BCE to 1,000 Common Era (CE) and includes the Ontario, Quebec, and Maritime regions.[13] The introduction of pottery distinguishes the Woodland culture from the previous Archaic-stage inhabitants. The Laurentian-related people of Ontario manufactured the oldest pottery excavated to date in Canada.[16]

The Hopewell tradition is an Aboriginal culture that flourished along American rivers from 300 BCE to 500 CE. At its greatest extent, the Hopewell Exchange System connected cultures and societies to the peoples on the Canadian shores of Lake Ontario. Canadian expression of the Hopewellian peoples encompasses the Point Peninsula, Saugeen, and Laurel complexes.[17][18][19]

The eastern woodland areas of what became Canada were home to the Algonquian and Iroquoian peoples. The Algonquian language is believed to have originated in the western plateau of Idaho or the plains of Montana and moved eastward,[20] eventually extending all the way from Hudson Bay to what is today Nova Scotia in the east and as far south as the Tidewater region of Virginia.

Pre-Columbian distribution of Algonquian languages in North America.

Pre-Columbian distribution of Algonquian languages in North America.

Speakers of eastern Algonquian languages included the Mi'kmaq and Abenaki of the Maritime region of Canada, and likely the extinct Beothuk of Newfoundland.[21][22] The Ojibwa and other Anishinaabe speakers of the central Algonquian languages retain an oral tradition of having moved to their lands around the western and central Great Lakes from the sea, likely the east coast. According to oral tradition the Ojibwa formed the Council of Three Fires in 796 CE with the Odawa and the Potawatomi.[23]

The Iroquois (Haudenosaunee) were centered from at least 1000 CE in northern New York, but their influence extended into what is now southern Ontario and the Montreal area of modern Quebec.[24] The Iroquois Confederacy, according to oral tradition, was formed in 1142 CE.[25][26] On the Great Plains the Cree or Nēhilawē (who spoke a closely related Central Algonquian language, the plains Cree language) depended on the vast herds of bison to supply food and many of their other needs.[27] To the north west were the peoples of the Na-Dene languages, which include the Athapaskan-speaking peoples and the Tlingit, who lived on the islands of southern Alaska and northern British Columbia. The Na-Dene language group is believed to be linked to the Yeniseian languages of Siberia.[28] The Dene of the western Arctic may represent a distinct wave of migration from Asia to North America.[28]

Pre-Columbian distribution of Na-Dene languages in North America

Pre-Columbian distribution of Na-Dene languages in North America

The Interior of British Columbia was home to the Salishan language groups such as the Shuswap (Secwepemc) and Okanagan and southern Athabaskan language groups, primarily the Dakelh (Carrier) and the Tsilhqot'in.[29] The inlets and valleys of the British Columbia Coast sheltered large, distinctive populations, such as the Haida, Kwakwaka'wakw and Nuu-chah-nulth, sustained by the region's abundant salmon and shellfish.[29] These peoples developed complex cultures dependent on the western red cedar that included wooden houses, seagoing whaling and war canoes and elaborately carved potlatch items and totem poles.[29] Defensive Salish trenchwork defences from the 16th century suggest a need for the southern Salish to take measures to protect themselves against their northern neighbours, who were known to mount raids into the Strait of Georgia and Puget Sound in historic times.[30]

In the Arctic archipelago, the distinctive Paleo-Eskimos known as Dorset peoples, whose culture has been traced back to around 500 CE, were replaced by the ancestors of today's Inuit by 1500 CE.[31] This transition is supported by archaeological records and Inuit mythology that tells of having driven off the Tuniit or 'first inhabitants'.[32] Inuit traditional laws are anthropologically different from Western law. Customary law was non-existent in Inuit society before the introduction of the Canadian legal system.[33]

European contact

Further information: Norse colonization of the AmericasThere are reports of contact made before the 1492 voyages of Christopher Columbus and the age of discovery between First Nations, Inuit and those from other continents. The earliest known documented European exploration of Canada is described in the Icelandic Sagas, which recount the attempted Norse colonization of the Americas.[34][35] According to the Sagas, the first European to see Canada was Bjarni Herjólfsson, who was blown off course en route from Iceland to Greenland in the summer of 985 or 986 CE.[36] Around the year 1001 CE, the Sagas then refer to Leif Ericson landing in three places to the west,[37] the first two being Helluland (possibly Baffin Island) and Markland (possibly Labrador).[35][38] Leif's third landing was at a place he called Vinland (possibly Newfoundland).[39] Norsemen (often referred to as Vikings) attempted to colonize the new land; they were driven out by the local climate and harassment by the Indigenous populace.[37][40] Archaeological evidence of a short-lived Norse settlement was found in L'Anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland.[41]

Based on the Treaty of Tordesillas, the Portuguese Crown claimed it had territorial rights in the area visited by John Cabot in 1497 and 1498 CE.[42] To that end, in 1499 and 1500, the Portuguese mariner João Fernandes Lavrador visited the north Atlantic coast, which accounts for the appearance of "Labrador" on topographical maps of the period.[43] Subsequently, in 1501 and 1502 the Corte-Real brothers explored Newfoundland and Labrador, claiming them as part of the Portuguese Empire.[44][45] In 1506, King Manuel I of Portugal created taxes for the cod fisheries in Newfoundland waters.[46] João Álvares Fagundes and Pêro de Barcelos established fishing outposts in Newfoundland and Nova Scotia around 1521 CE; however, these were later abandoned, with the Portuguese colonizers focusing their efforts on South America.[47] The extent and nature of Portuguese activity on the Canadian mainland during the 16th century remains unclear and controversial.[48][49]

New France and colonization 1534–1763

Main articles: New France and Former colonies and territories in Canada Replica of Port Royal habitation, located at the Port-Royal National Historic Site of Canada, Nova-Scotia.[50]

Replica of Port Royal habitation, located at the Port-Royal National Historic Site of Canada, Nova-Scotia.[50]

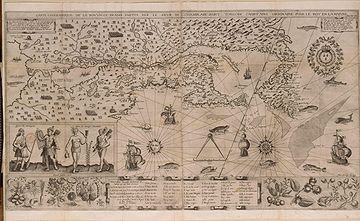

French interest in the New World began with Francis I of France, who in 1524 sponsored Giovanni da Verrazzano to navigate the region between Florida and Newfoundland in hopes of finding a route to the Pacific Ocean.[51] In 1534, Jacques Cartier planted a cross in the Gaspé Peninsula and claimed the land in the name of Francis I.[52] Initial French attempts at settling the region met with failure. French fishing fleets continued to sail to the Atlantic coast and into the Saint Lawrence River, trading and making alliances with First Nations.[52] In 1600, a trading post was established at Tadoussac by François Gravé Du Pont, a merchant, and Pierre de Chauvin de Tonnetuit, a captain of the French Royal Navy.[53] However, only five of the sixteen settlers (all male) survived the first winter and returned to France.[53]

In 1604, a North American fur trade monopoly was granted to Pierre Dugua Sieur de Monts.[54] Dugua led his first colonization expedition to an island located near to the mouth of the St. Croix River. Among his lieutenants was a geographer named Samuel de Champlain, who promptly carried out a major exploration of the northeastern coastline of what is now the United States.[54] In the spring of 1605, under Samuel de Champlain, the new St. Croix settlement was moved to Port Royal (today's Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia) then abandoned in 1607.[50][53]

Champlain then founded what is now Quebec City in 1608. It would become the first permanent settlement and the capital of New France. Champlain took personal administration over the city and its affairs and sent out expeditions to explore the interior land. Champlain himself discovered Lake Champlain in 1609. By 1615, he had travelled by canoe up the Ottawa River through Lake Nipissing and Georgian Bay to the center of Huron country near Lake Simcoe.[55] During these voyages, Champlain aided the Wendat (aka 'Hurons') in their battles against the Iroquois Confederacy.[56] As a result, the Iroquois would become enemies of the French and be involved in multiple conflicts (known as the French and Iroquois Wars) until the signing of the Great Peace of Montreal in 1701.[57]

The English lead by Sir Humphrey Gilbert had claimed St. John's, Newfoundland in 1583 as the first North American English colony by royal prerogative of Queen Elizabeth I.[58] The English would established additional colonies in Cupids and Ferryland, Newfoundland beginning in 1610 and soon after founded the Thirteen Colonies to the south.[59] On the September 29, 1621, a charter for the foundation of a New World Scottish colony was granted by James VI of Scotland to Sir William Alexander.[60] In 1622, the first settlers left Scotland. They initially failed and permanent Nova Scotian settlements were not firmly established until 1629 during the end of the Anglo-French War.[60] These colonies did not last long: in 1631, under Charles I of England, the Treaty of Suza was signed, ending the war and returning Nova Scotia to the French.[61] New France was not fully restored to French rule until the 1632 Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye.[62] This led to new French immigrants and the founding of Trois-Rivières in 1634, the second permanent settlement in New France.[63]

After Champlain’s death in 1635, the Catholic Church and the Jesuit establishment became the most dominant force in New France and intended to establish a utopian European and Aboriginal Christian community.[64] In 1642, the Jesuit (Society of Jesus) sponsored a group of settlers, led by Paul Chomedey de Maisonneuve, who founded Ville-Marie, precursor to present-day Montreal.[65] The 1666 census of New France was conducted by France's intendant, Jean Talon, in the winter of 1665–1666. The census showed a population count of 3,215 Acadians and habitants in the administrative districts of Acadia and Canada (New France).[66] The census also revealed a great difference in the number of men at 2,034 versus 1,181 women.[67]

Wars during the colonial era

Further information: French and Indian WarsWhile the French settlers were established in modern Quebec and Nova Scotia, new arrivals stopped coming from France. By 1680 the French population was around 11,000[68] and they were outnumbered by at over 10-1 by the Thirteen Colonies British colonies to the South. From 1670, through the Hudson's Bay Company, the English also laid claim to Hudson Bay, and its drainage basin (known as Rupert's Land), and operated fishing settlements in Newfoundland.[69] La Salle's explorations gave France a claim to the Mississippi River Valley, where fur trappers and a few settlers set up scattered settlements.[70] French expansion challenged the Hudson's Bay Company claims, and in 1686 Pierre Troyes led an overland expedition from Montreal to the shore of the bay, where they managed to capture some areas.[71]

There were four French and Indian Wars between the Thirteen American Colonies and New France from 1689 to 1763. During King William's War (1689 to 1697) military conflicts in Acadia included: Battle of Port Royal (1690); a naval battle in the Bay of Fundy (Action of July 14, 1696); and the Raid on Chignecto (1696) .[72] The Treaty of Ryswick in 1697 ended the war between the two colonial powers of England and France for a brief time.[73] During Queen Anne's War (1702 to 1713), the British Conquest of Acadia occurred in 1710.[74] Resulting in Nova Scotia, other than Cape Breton, being officially ceded to the British by the Treaty of Utrecht including Rupert's Land, that had been conquered by France in the late 17th century (Battle of Hudson's Bay).[75] As an immediate result of this setback, France founded the powerful Fortress of Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island.[76] Louisbourg was intended to serve as a year-round military and naval base for France's remaining North American empire and to protect the entrance to the Saint Lawrence River. During King George's War (1744 to 1748), an army of New Englanders led by William Pepperrell mounted an expedition of 90 vessels and 4,000 men against Louisbourg in 1745.[77] Within three months the fortress surrendered. The return of Louisbourg to French control by the peace treaty prompted the British to found Halifax in 1749 under Edward Cornwallis.[78] Despite the official cessation of war between the British and French empires with the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle; the conflict in Acadia and Nova Scotia continued on as the Father Le Loutre's War.[79]

St. John River Campaign: Raid on Grimrose (present day Gagetown, New Brunswick). This is the only contemporaneous image of the Expulsion of the Acadians

The British ordered the Acadians expelled from their lands in 1755 during the French and Indian War, an event called the Expulsion of the Acadians or le Grand Dérangement.[80] The "expulsion" resulted in approximately 12,000 Acadians being shipped to destinations throughout Britain's North American and to France, Quebec and the French Caribbean colony of Saint-Domingue.[81] The first wave of the expulsion of the Acadians began with the Bay of Fundy Campaign (1755) and the second wave began after the final Siege of Louisbourg (1758). Many of the Acadians settled in southern Louisiana, creating the Cajun culture there.[81] Some Acadians managed to hide and others eventually returned to Nova Scotia, but they were far outnumbered by a new migration of New England Planters who were settled on the former lands of the Acadians and transformed Nova Scotia from a colony of occupation for the British to a settled colony with stronger ties to New England.[81] Britain eventually gained control of Quebec City and Montreal after the Battle of the Plains of Abraham and Battle of Fort Niagara in 1759, and the Battle of the Thousand Islands and Battle of Sainte-Foy in 1760.[82]

Canada under British rule (1763–1867)

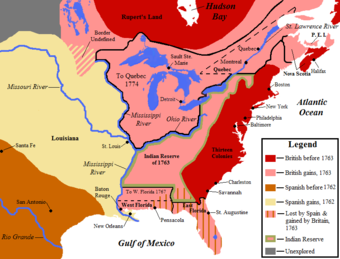

Main article: Canada under British rule (1763–1867) Map showing British territorial gains following the "Seven Years' War". Treaty of Paris gains in pink, and Spanish territorial gains after the Treaty of Fontainebleau in yellow.

Map showing British territorial gains following the "Seven Years' War". Treaty of Paris gains in pink, and Spanish territorial gains after the Treaty of Fontainebleau in yellow.

With the end of the Seven Years' War and the signing of the Treaty of Paris (1763), France ceded almost all of its territory in mainland North America, except for fishing rights off Newfoundland and two small islands where it could dry that fish. In turn France received the return of its sugar colony, Guadeloupe, which it considered more valuable than Canada.[83]

The new British rulers retained and protected most of the property, religious, political, and social culture of the French-speaking habitants, guaranteeing the right of the Canadiens to practice the Catholic faith and to the use of French civil law (now Quebec law) through the Quebec Act of 1774.[84] The Royal Proclamation of 1763 had been issued in October, by King George III following Great Britain's acquisition of French territory.[85] The proclamation organized Great Britain's new North American empire and to stabilize relations between the British Crown and Aboriginal peoples through regulation of trade, settlement, and land purchases on the western frontier.[85]

American Revolution and Loyalists

Further information: Invasion of Canada (1775)During the American Revolution there was some sympathy for the American cause among the Canadiens and the New Englanders in Nova Scotia.[86] Neither party joined the rebels, although several hundred individuals joined the revolutionary cause.[86][87] An invasion of Canada; by the Continental Army in 1775, to take Quebec from British control was halted at the Battle of Quebec, by Guy Carleton, with the assistance of local militias. The defeat of the British army during the Siege of Yorktown in October 1781, signaled the end of Britain's struggle to suppress the American Revolution.[88] When the British evacuated New York City in 1783, they took many Loyalist refugees to Nova Scotia, while other Loyalists went to southwestern Quebec. So many Loyalists arrived on the shores of the St. John River that a separate colony—New Brunswick—was created in 1784;[89] followed in 1791 by the division of Quebec into the largely French-speaking Lower Canada along the Saint Lawrence River and Gaspé Peninsula and an anglophone Loyalist Upper Canada, with its capital settled by 1796 in York, in present-day Toronto.[90] After 1790 most of the new settlers were American farmers searching for new lands; although generally favorable to republicanism, they were relatively non-political and stayed neutral in the War of 1812.[91]

The signing of the Treaty of Paris 1783, formally ended the war. Britain made several concessions to the Americans at the expense of the North American colonies.[92] Notably, the borders between Canada and the United States were officially demarkated.[92] All land south of the Great Lakes, which was formerly a part of the Province of Quebec and included modern day Michigan, Illinois and Ohio, was ceded to the Americans. Fishing rights were also granted to the United States in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and on the coast of Newfoundland and the Grand Banks.[92] The British ignored part of the treaty and maintained their military outposts in the Great Lakes areas it ceded to the U.S., and continued to supply the Indians there with munitions. The British evacuated the outposts with the Jay Treaty of 1795, but the continued supply of munitions irritated the Americans in the run-up to the war of 1812.[93]

War of 1812

Loyalist Laura Secord warning the British (Lieutenant – James FitzGibbon) and First Nations of an impending American attack at Beaver Dams June 1813. – by Lorne Kidd Smith, c. 1920

Loyalist Laura Secord warning the British (Lieutenant – James FitzGibbon) and First Nations of an impending American attack at Beaver Dams June 1813. – by Lorne Kidd Smith, c. 1920 Main article: War of 1812

Main article: War of 1812The War of 1812 was fought between the United States and the British with the British North American colonies being heavily involved.[94] Greatly outgunned by the British Royal Navy, the American war plans focused on an invasion of Canada (especially what is today eastern and western Ontario). The American frontier states voted for war to suppress the First Nations raids that frustrated settlement of the frontier.[94] The war on the border with the U.S. was characterized by a series of multiple failed invasions and fiascos on both sides. American forces took control of Lake Erie in 1813, driving the British out of western Ontario, killing the Native American leader Tecumseh, and breaking the military power of his confederacy.[95] The war was overseen by Isaac Brock, with the assistance of First Nations and loyalist informants like Laura Secord.[96]

The War ended with the Treaty of Ghent of 1814, and the Rush–Bagot Treaty of 1817.[94] A demographic result was the shifting of American migration from Upper Canada to Ohio, Indiana and Michigan.[94] After the war, supporters of Britain tried to repress the republicanism in Canada, that was common among American immigrants to Canada.[94] The troubling memory of the war and the American invasions etched itself into the consciousness of Canadians as distrust of the intentions of the United States towards the British presence in North America.[97]pp. 254–255

Rebellions and the Durham Report

Further information: Rebellions of 1837The rebellions of 1837 against the British colonial government took place in both Upper and Lower Canada. In Upper Canada, a band of Reformers under the leadership of William Lyon Mackenzie took up arms in a disorganized and ultimately unsuccessful series of small-scale skirmishes around Toronto, London, and Hamilton.[98]

In Lower Canada, a more substantial rebellion occurred against British rule. Both English- and French-Canadian rebels, sometimes using bases in the neutral United States, fought several skirmishes against the authorities. The towns of Chambly and Sorel were taken by the rebels, and Quebec City was isolated from the rest of the colony. Montreal rebel leader Robert Nelson read the "Declaration of Independence of Lower Canada" to a crowd assembled at the town of Napierville in 1838.[99] The rebellion of the Patriote movement were defeated after battles across Quebec. Hundreds were arrested, and several villages were burnt in reprisal.[99]

British Government then sent Lord Durham to examine the situation, he stayed in Canada only five months before returning to Britain, and brought with him, his Durham Report which strongly recommended responsible government.[100] A less well received recommendation was the amalgamation of Upper and Lower Canada for the deliberate assimilation of the French-speaking population. The Canadas were merged into a single colony, United Province of Canada, by the 1840 Act of Union, with responsible government achieved in 1848, a few months after it was granted to Nova Scotia.[100] The parliament of United Canada in Montreal was set on fire by a mob of Tories in 1849 after the passing of an indemnity bill for the people who suffered losses during the rebellion in Lower Canada.[101]

Between the Napoleonic Wars and 1850 some 800,000 immigrants came to the colonies of British North America, mainly from the British Isles as part of the great migration of Canada.[102] These included Gaelic-speaking Highland Scots displaced by the Highland Clearances to Nova Scotia and Scottish and English settlers to the Canadas, particularly Upper Canada. The Irish Famine of the 1840s significantly increased the pace of Irish Catholic immigration to British North America, with over 35,000 distressed Irish landing in Toronto alone in 1847 and 1848.[103]

Pacific colonies

Further information: History of British ColumbiaSpanish explorers had taken the lead in the Pacific Northwest coast, with the voyages of Juan José Pérez Hernández in 1774 and 1775.[104] By the time the Spanish determined to build a fort on Vancouver Island, the British navigator James Cook had visited Nootka Sound and charted the coast as far as Alaska, while British and American maritime fur traders had begun a busy era of commerce with the coastal peoples to satisfy the brisk market for sea otter pelts in China, thereby launching what became known as the China Trade.[105]

In 1789 war threatened between Britain and Spain on their respective rights; the Nootka Crisis was resolved peacefully largely in favor of Britain, the much stronger naval power. In 1793 Alexander MacKenzie, a Canadian working for the North West Company, crossed the continent and with his Aboriginal guides and French-Canadian crew, reached the mouth of the Bella Coola River, completing the first continental crossing north of Mexico, missing George Vancouver's charting expedition to the region by only a few weeks.[106] In 1821, the North West Company and Hudson's Bay Company merged, with a combined trading territory that was extended by a licence to the North-Western Territory and the Columbia and New Caledonia fur districts, which reached the Arctic Ocean on the north and the Pacific Ocean on the west.[107]

The Colony of Vancouver Island was chartered in 1849, with the trading post at Fort Victoria as the capital. This was followed by the Colony of the Queen Charlotte Islands in 1853, and by the creation of the Colony of British Columbia in 1858 and the Stikine Territory in 1861, with the latter three being founded expressly to keep those regions from being overrun and annexed by American gold miners.[108] The Colony of the Queen Charlotte Islands and most of the Stikine Territory were merged into the Colony of British Columbia in 1863 (the remainder, north of the 60th Parallel, became part of the North-Western Territory).[108]

Confederation

Main article: Canadian Confederation 1885 photo of Robert Harris' 1884 painting, Conference at Quebec in 1864, also known as The Fathers of Confederation. The scene is an amalgamation of the Charlottetown and Quebec City conference sites and attendees.

1885 photo of Robert Harris' 1884 painting, Conference at Quebec in 1864, also known as The Fathers of Confederation. The scene is an amalgamation of the Charlottetown and Quebec City conference sites and attendees.

The Seventy-Two Resolutions from the 1864 Quebec Conference and Charlottetown Conference laid out the framework for uniting British colonies in North America into a federation.[109] They had been adopted by the majority of the provinces of Canada and became the basis for the London Conference of 1866, which led to the formation of the Dominion of Canada on July 1, 1867.[109] The term dominion was chosen to indicate Canada's status as a self-governing colony of the British Empire, the first time it was used about a country.[110] With the coming into force of the British North America Act (enacted by the British Parliament), the Province of Canada, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia became a federated kingdom in its own right.[111][112][113]

Federation emerged from multiple impulses: the British wanted Canada to defend itself; the Maritimes needed railroad connections, which were promised in 1867; British-Canadian nationalism sought to unite the lands into one country, dominated by the English language and British culture; many French-Canadians saw an opportunity to exert political control within a new largely French-speaking Quebec[97]pp. 323–324 and fears of possible U.S. expansion northward.[110] On a political level, there was a desire for the expansion of responsible government and elimination of the legislative deadlock between Upper and Lower Canada, and their replacement with provincial legislatures in a federation.[110] This was especially pushed by the liberal Reform movement of Upper Canada and the French-Canadian Parti rouge in Lower Canada who favored a decentralized union in comparison to the Upper Canadian Conservative party and to some degree the French-Canadian Parti bleu, which favored a centralized union.[110][114]

Post-Confederation Canada 1867–1914

Main article: Post-Confederation Canada (1867–1914)Further information: Territorial evolution of Canada The Battle of Fish Creek, fought April 24, 1885 at Fish Creek, Saskatchewan, was a major Métis victory over the Dominion of Canada forces attempting to quell Louis Riel's North-West Rebellion.

The Battle of Fish Creek, fought April 24, 1885 at Fish Creek, Saskatchewan, was a major Métis victory over the Dominion of Canada forces attempting to quell Louis Riel's North-West Rebellion.

In 1866, the Colony of British Columbia and the Colony of Vancouver Island merged into a single Colony of British Columbia, until their incorporation into the Canadian Confederation in 1871.[115] In 1873, Prince Edward Island, the Maritime colony that had opted not to join Confederation in 1867, was admitted into the country.[115] That year, John A. Macdonald (First Prime Minister of Canada) created the North-West Mounted Police (now the Royal Canadian Mounted Police) to help police the Northwest Territories.[116] Specifically the Mounties were to assert Canadian sovereignty over possible American encroachments into the sparsely populated land.[116]

The Mounties first large scale mission was to suppress the second independence movement by Manitoba's Métis, a mixed blood people of joint First Nations and European descent, who originated in the mid-17th century.[117] The desire for independence erupted in the Red River Rebellion in 1869 and the later North-West Rebellion in 1885 led by Louis Riel.[116][118] In 1905 when Saskatchewan and Alberta were admitted as provinces, they were growing rapidly thanks to abundant wheat crops that attracted immigration to the plains by Ukrainians and Northern and Central Europeans and by settlers from the United States, Britain and eastern Canada.[119][120]

The Alaska boundary dispute, simmering since the Alaska purchase of 1867, became critical when gold was discovered in the Yukon during the late 1890s, with the U.S. controlling all the possible ports of entry. Canada argued its boundary included the port of Skagway. The dispute went to arbitration in 1903, but the British delegate sided with the Americans, angering Canadians who felt the British had betrayed Canadian interests to curry favour with the U.S. [121]

In 1893, legal experts codified a framework of civil and criminal law, culminating in the Criminal Code of Canada. This solidified the liberal ideal of "equality before the law" in a way that made an abstract principle into a tangible reality for every adult Canadian.[122] Wilfrid Laurier who served 1896–1911 as the Seventh Prime Minister of Canada felt Canada was on the verge of becoming a world power, and declared that the 20th century would "belong to Canada"[123]

World Wars and Interwar Years 1914–1945

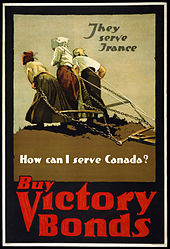

Main article: Canada in the World Wars and Interwar Years World War I poster for 1918– Canadian victory bond drive, depicts three French women pulling a plow.

World War I poster for 1918– Canadian victory bond drive, depicts three French women pulling a plow.

The Canadian Forces and civilian participation in the First World War helped to foster a sense of British-Canadian nationhood. The highpoints of Canadian military achievement during the First World War came during the Somme, Vimy, Passchendaele battles and what later became known as "Canada's Hundred Days".[124] The reputation Canadian troops earned, along with the success of Canadian flying aces including William George Barker and Billy Bishop, helped to give the nation a new sense of identity.[125] The War Office in 1922 reported approximately 67,000 killed and 173,000 wounded during the war.[126] This excludes civilian deaths in war time incidents like the Halifax Explosion.[126]

Support for Great Britain during the First World War caused a major political crisis over conscription, with Francophones, mainly from Quebec, rejecting national policies.[127] During the crisis large numbers of enemy aliens (especially Ukrainians and Germans) were put under government controls.[128] The Liberal party was deeply split, with most of its Anglophone leaders joining the unionist government headed by Prime Minister Robert Borden, the leader of the Conservative party.[129] The Liberals regained their influence after the war under the leadership of William Mackenzie King, who served as prime minister with three separate terms between 1921 and 1949.[130]

As a result of the First World War, the Government of Canada became more assertive and less deferential to British authority; it became an independent member of the League of Nations.[131] In 1931 the Statute of Westminster gave each dominion (which included Canada and Newfoundland) the opportunity for almost complete legislative independence from the Parliament of the United Kingdom.[132] While Newfoundland never adopted the statute, for Canada the Statute of Westminster has been called its declaration of independence.[133]

The great depression in Canada during the interwar period affected all parts of daily life.[134] It hit especially hard in western Canada, where a full recovery did not occur until the Second World War began in 1939. Hard times led to the creation of new political parties such as the Social Credit movement and the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation, as well as popular protest in the form of the On-to-Ottawa Trek.[135] The period also saw the rise of a small Communist Party of Canada, who opposed Canada's entry into Second World War and was subsequently banned under the Defence of Canada Regulations of the War Measures Act in 1940.

Canada's involvement in the Second World War began when Canada declared war on Nazi Germany on September 10, 1939, one week after the United Kingdom. The Battle of the Atlantic began immediately, and from 1943 to 1945 was led by Leonard W. Murray, from Nova Scotia. The Canadian army was involved in the defence of Hong Kong, the Dieppe Raid in August 1942, the Allied invasion of Italy, and the Battle of Normandy. Axis U-boats operated in Canadian and Newfoundland waters throughout the war, sinking many naval and merchant vessels.[136] The Canadian mainland was also attacked when the Japanese submarine I-26 shelled the Estevan Point lighthouse on Vancouver Island.[137]

The Conscription Crisis of 1944 greatly affected unity between French and English-speaking Canadians, though was not as politically intrusive as that of the First World War.[138] Of a population of approximately 11.5 million, 1.1 million Canadians served in the armed forces in the Second World War.[139] Many thousands more served with the Canadian Merchant Navy.[140] In all, more than 45,000 died, and another 55,000 were wounded.[141][142]

Post-war Era 1945–1960

Main article: History of Canada (1945–1960)Prosperity returned to Canada during the Second World War and continued in the proceeding years, with the development of universal health care, old-age pensions, and veterans' pensions.[143][144] The financial crisis of the Great Depression had led the Dominion of Newfoundland to relinquish responsible government in 1934 and become a crown colony ruled by a British governor.[145] In 1948, the British government gave voters three Newfoundland Referendum choices: remaining a crown colony, returning to Dominion status (that is, independence), or joining Canada. Joining the United States was not made an option. After bitter debate Newfoundlanders voted to join Canada in 1949 as a province.[146]

The Avro Canada CF-105 Arrow (Recreation).

The Avro Canada CF-105 Arrow (Recreation).

The foreign policy of Canada during the Cold War was closely tied to that of the United States. Canada was a founding member of NATO (which Canada wanted to be a transatlantic economic and political union as well[147]). In 1950 Canada sent combat troops to Korea during the Korean War as part of the United Nations forces. The federal government's desire to assert its territorial claims in the Arctic during the Cold War manifested with the High Arctic relocation, in which Inuit were moved from Nunavik (the northern third of Quebec) to barren Cornwallis Island;[148] this project was later the subject of a long investigation by the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples.[149]

In 1956, the United Nations responded to the Suez Crisis by convening a United Nations Emergency Force to supervise the withdrawal of invading forces. The peacekeeping force was initially conceptualized by Secretary of External Affairs and future Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson.[150] Pearson was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1957 for his work in establishing the peacekeeping operation.[150] Throughout the mid-1950s Louis St. Laurent (12th Prime Minister of Canada) and his successor John George Diefenbaker attempted to create a new, highly advanced jet fighter, the Avro Arrow.[151] The controversial aircraft was cancelled by Diefenbaker in 1959. Diefenbaker instead purchased the BOMARC missile defense system and American aircraft. In 1958 Canada established (with the United States) the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD).[152]

1960–1981

Main article: History of Canada (1960–1981)In the 1960s, what became known as the Quiet Revolution took place in Quebec, overthrowing the old establishment which centered on the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Quebec and led to modernizing of the economy and society.[153] Québécois nationalists demanded independence, and tensions rose until violence erupted during the 1970 October Crisis.[154] In 1976 the Parti Québécois was elected to power in Quebec, with a nationalist vision that included securing French linguistic rights in the province and the pursuit of some form of sovereignty for Quebec. This culminated in the 1980 referendum in Quebec on the question of sovereignty-association, which was turned down by 59% of the voters.[154]

In 1965, Canada adopted the maple leaf flag, although not without considerable debate and misgivings among large number of English Canadians.[155] The World's Fair titled Expo 67 came to Montreal, coinciding with the Canadian Centennial that year. The fair opened April 28, 1967, with the theme "Man and his World" and became the best attended of all BIE-sanctioned world expositions until that time.[156]

Legislative restrictions on Canadian immigration that had favoured British and other European immigrants were amended in the 1960s, opening the doors to immigrants from all parts of the world.[157] While the 1950s had seen high levels of immigration from Britain, Ireland, Italy, and northern continental Europe, by the 1970s immigrants increasingly came from India, China, Vietnam, Jamaica and Haiti.[158] Immigrants of all backgrounds tended to settle in the major urban centres, particularly Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver.[158]

During his long tenure in the office (1968–79, 1980–84), Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau made social and cultural change his political goals, including the pursuit of official bilingualism in Canada and plans for significant constitutional change.[159] The west, particularly the petroleum-producing provinces like Alberta, opposed many of the policies emanating from central Canada, with the National Energy Program creating considerable antagonism and growing western alienation.[160]

1982–1992

Main article: History of Canada (1982–1992)In 1982, the Canada Act was passed by the British parliament and granted Royal Assent by Queen Elizabeth II on March 29, while the Constitution Act was passed by the Canadian parliament and granted Royal Assent by the Queen on April 17, thus patriating the Constitution of Canada.[161] Previously, the constitution has existed only as an act passed of the British parliament, and was not even physically located in Canada, though it could not be altered without Canadian consent.[162] At the same time, the Charter of Rights and Freedoms was added in place of the previous Bill of Rights.[163] The patriation of the constitution was Trudeau's last major act as Prime Minister; he resigned in 1984.

Pte. Patrick Cloutier, a 'Van Doo' perimeter sentry, and Mohawk Warrior Brad Larocque, a University of Saskatchewan economics student, face off during the Oka Crisis[164]

Pte. Patrick Cloutier, a 'Van Doo' perimeter sentry, and Mohawk Warrior Brad Larocque, a University of Saskatchewan economics student, face off during the Oka Crisis[164]

On June 23, 1985, Air India Flight 182 was destroyed above the Atlantic Ocean by a bomb on board exploding; all 329 on board were killed, of whom 280 were Canadian citizens.[165] The Air India attack is the largest mass murder in Canadian history.[166]

The Progressive Conservative (PC) government of Brian Mulroney began efforts to gain Quebec's support for the Constitution Act 1982 and end western alienation. In 1987 the Meech Lake Accord talks began between the provincial and federal governments, seeking constitutional changes favourable to Quebec.[167] The constitutional reform process under Prime Minister Mulroney culminated in the failure of the Charlottetown Accord which would have recognized Quebec as a "distinct society" but was rejected in 1992 by a narrow margin.[168]

Under Brian Mulroney, relations with the United States began to grow more closely integrated. In 1986, Canada and the U.S. signed the "Acid Rain Treaty" to reduce acid rain. In 1989, the federal government adopted the Free Trade Agreement with the United States despite significant animosity from the Canadian public who were concerned about the economic and cultural impacts of close integration with the United States.[169] On July 11, 1990, the Oka Crisis land dispute began between the Mohawk people of Kanesatake and the adjoining town of Oka, Quebec.[170] The dispute was the first of a number of well-publicized conflicts between First Nations and the Canadian government in the late 20th century. In August 1990, Canada was one of the first nations to condemn Iraq's invasion of Kuwait, and it quickly agreed to join the U.S.-led coalition. Canada deployed destroyers and later a CF-18 Hornet squadron with support personnel, as well as a field hospital to deal with casualties.[171]

Recent history: 1992–present

Main article: History of Canada (1992–present)Following Mulroney's resignation as prime minister in 1993, Kim Campbell took office and became Canada's first female prime minister.[172] Campbell remained in office only for a few months: the 1993 election saw the collapse of the Progressive Conservative Party from government to two seats, while the Quebec-based sovereigntist Bloc Québécois became the official opposition.[173] Prime Minister Jean Chrétien of the Liberals took office in November 1993 with a majority government and was re-elected with further majorities during the 1997 and 2000 elections.[174]

In 1995, the government of Quebec held a second referendum on sovereignty that was rejected by a margin of 50.6% to 49.4%.[175] In 1998, the Canadian Supreme Court ruled unilateral secession by a province to be unconstitutional, and Parliament passed the Clarity Act outlining the terms of a negotiated departure.[175] Environmental issues increased in importance in Canada during this period, resulting in the signing of the Kyoto Accord on climate change by Canada's Liberal government in 2002. The accord was in 2007 nullified by the present government, which has proposed a "made-in-Canada" solution to climate change.[176]

Canada became the fourth country in the world and the first country in the Americas to legalize same-sex marriage nationwide with the enactment of the Civil Marriage Act.[177] Court decisions, starting in 2003, had already legalized same-sex marriage in eight out of ten provinces and one of three territories. Before the passage of the Act, more than 3,000 same-sex couples had married in these areas.[178]

The Canadian Alliance and PC Party merged into the Conservative Party of Canada in 2003, ending a 13-year division of the conservative vote. The party was elected twice as a minority government under the leadership of Stephen Harper in the 2006 federal election and 2008 federal election.[179] Harper's Conservative Party won a majority in the 2011 federal election with the New Democratic Party forming the Official Opposition for the first time.[180]

Under Harper, Canada and the United States continue to integrate state and provincial agencies to strengthen security along the Canada-United States border through the Western Hemisphere Travel Initiative.[181] From 2002 to 2011, Canada was involved in the Afghanistan War as part of the U.S. stabilization force and the NATO-commanded International Security Assistance Force. In July 2010 the largest purchase in Canadian military history, totalling C$9 billion for the acquisition of 65 F-35 fighters, was announced by the federal government.[182] Canada is one of several nations that assisted in the development of the F-35 and has invested over C$168 million in the program.[183]

See also

History by province or territory - Events of National Historic Significance (Canada)

- History of the Americas

- History of Montreal

- History of North America

- History of Ottawa

- History of Quebec City

- History of Toronto

- History of Vancouver

- History of Winnipeg

- National Historic Sites of Canada

- Persons of National Historic Significance

References

- ^ "Atlas of the Human Journey-The Genographic Project". National Geographic Society.. 1996-2008. https://genographic.nationalgeographic.com/genographic/atlas.html?era=e003. Retrieved 2009-10-06.

- ^ a b "Alternate Migration Corridors for Early Man in North America". American Antiquity, Vol. 44, No. 1 (Jan., 1979), p2. http://archaeology.about.com/gi/o.htm?zi=1/XJ&zTi=1&sdn=archaeology&cdn=education&tm=25&f=00&tt=13&bt=1&bts=1&zu=http%3A//www.jstor.org/stable/279189. Retrieved 2009-10-06.

- ^ "An mtDNA view of the peopling of the world by Homo sapiens". Cambridge DNA Services. 2007. https://www.cambridgedna.com/genealogy-dna-ancient-migrations-slideshow.php?view=step7. Retrieved 2011-06-01.

- ^ "The Late Pleistocene Dispersal of Modern Humans in the Americas" (PDF). Ted Goebel, et al (The Center for the Study of First Americans). 2008. doi:10.1126/science.1153569. http://www.centerfirstamericans.com/cfsa-publications/Science2008.pdf. Retrieved 2010-02-05.

- ^ Than, Ker (2008). "New World Settlers Took 20,000-Year Pit Stop". National Geographic Society. http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2008/02/080214-america-layover.html. Retrieved 2010-01-23.

- ^ Jordan, David K (2009). "Prehistoric Beringia". University of California-San Diego. http://www.anthro.ucsd.edu/~dkjordan/arch/beringia.html. Retrieved 2010-04-15.

- ^ "Vertebrate paleontology and the alleged ice-free corridor: The meat of the matter". http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6VGS-3VW7XG3-8&_user=10&_rdoc=1&_fmt=&_orig=search&_sort=d&_docanchor=&view=c&_searchStrId=997406958&_rerunOrigin=google&_acct=C000050221&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=10&md5=35352485ac241d4d8759c83f01e4aa74. Retrieved 2010-06-20.

- ^ "Pleistocene Archaeology of the Old Crow Flats". Vuntut National Park of Canada. 2008. http://yukon.taiga.net/vuntutrda/archaeol/info.htm. Retrieved 2010-01-10. "However, despite the lack of this conclusive and widespread evidence, there are suggestions of human occupation in the northern Yukon about 24,000 years ago, and hints of the presence of humans in the Old Crow Basin as far back as about 40,000 years ago."

- ^ "Introduction". Government of Canada. Parks Canada. 2009. http://www.pc.gc.ca/eng/docs/r/pfa-fap/sec1.aspx. Retrieved 2010-01-09. "Canada's oldest known home is a cave in Yukon occupied not 12,000 years ago as at U.S. sites, but at least 20,000 years ago"

- ^ Carlson, Roy L; Dalla Bona, Luke Robert (1996). Early human occupation in British Columbia. University of British Columbia Press. pp. 149–152. ISBN 0774805366. http://books.google.ca/books?id=KT4A5dHuiSgC&lpg=PP1&dq=Haida%20Gwaii%3A%20Human%20History%20and%20Environment%20from%20the%20Time%20of%20the%20Loon%20to%20the%20Time&pg=PA152#v=onepage&q&f=true. Retrieved 2010-04-29.

- ^ Cinq-Mars, Jacques (2001). "Significance of the Bluefish Caves in Beringian Prehistory". Canadian Museum of Civilization. p. 2. http://www.civilization.ca/cmc/explore/resources-for-scholars/essays/archaeology/jacques-cinq-mars/significance-of-the-bluefish-caves-in-beringian-prehistory2#four. Retrieved 2010-04-15.

- ^ Gibbon, Guy E; Ames, Kenneth M (1998). Old Crow Flats. Routledge. p. 682. ISBN 081530725X. http://books.google.ca/books?id=_0u2y_SVnmoC&lpg=PA682&dq=archaeology%20of%20the%20Old%20Crow%20Flats&pg=PA682#v=onepage&q&f=true. Retrieved 2010-04-11.

- ^ a b "C. Prehistoric Periods (Eras of Adaptation)". The University of Calgary (The Applied History Research Group). 2000. http://www.ucalgary.ca/applied_history/tutor/firstnations/periods.html. Retrieved 2010-04-15.

- ^ Imbrie, J; K.P.Imbrie (1979). Ice Ages: Solving the Mystery. Short Hills NJ: Enslow Publishers. ISBN 0226668118.

- ^ a b Fiedel, Stuart J (1992). Prehistory of the Americas. Cambridge University Press. p. 84. http://books.google.ca/books?id=Yrhp8H0_l6MC&lpg=PA151&dq=Paleo-Indians%20tradition&pg=PR5#v=onepage&q&f=true. Retrieved 2010-06-20.

- ^ Fagan, Brian M (1992). People of the Earth: An Introduction to World Prehistory. University of California. Harper Collins. ISBN 032101457X.

- ^ "A History of the Native People of Canada". Dr. James V. Wright. Canadian Museum of Civilization. 2009. http://www.civilization.ca/cmc/exhibitions/archeo/hnpc/npvol25e.shtml. Retrieved 2009-10-09.

- ^ Ohio Historical Society (2009). "Hopewell Culture-Ohio History Central-A product of the Ohio Historical Society". Hopewell-Ohio History Central. http://www.ohiohistorycentral.org/entry.php?rec=1283. Retrieved 2009-09-18.

- ^ Douglas T. Price, and Gary M. Feinman (2008). Images of the Past, 5th edition. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 274–277. ISBN 978-0 07-3405209.

- ^ Ives Goddard, 1994. "The West-to-East Cline in Algonquian Dialectology." In Actes du Vingt-Cinquième Congrès des Algonquinistes, ed. William Cowan: 187–211. Ottawa: Carleton University

- ^ Marshall, Ingeborg (1998). A History and Ethnography of the Beothuk. McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 237. ISBN 077351774X. http://books.google.ca/books?id=ckOav3Szu7oC&lpg=PA437&dq=Beothuk%20eastern%20Algonquian%20languages&pg=PA437#v=onepage&q&f=true. Retrieved 2011-01-16.

- ^ "Maliseet and Mi'kmaq Languages". Government of New Brunswick – Aboriginal Affairs Secretariat. 1995. http://www.gnb.ca/0016/wolastoqiyik/languages-e.asp. Retrieved 2010-04-15.

- ^ "Background 1: Ojibwa history". Department of Science and Technology Studies · The Center for Cultural Design. 2003. http://csdt.rpi.edu/na/arcs/background1.html. Retrieved 2010-04-15.

- ^ "Iroquois". The Canadian Encyclopedia. 2008. http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com/index.cfm?PgNm=TCE&Params=A1SEC877040. Retrieved 2010-04-11.

- ^ Johansen, Bruce (1995). "Dating the Iroquois Confederacy". Akwesasne Notes New Series 1 (3): 62–63. http://www.ratical.org/many_worlds/6Nations/DatingIC.html. Retrieved 2010-08-36.

- ^ Johansen,, Bruce Elliott; Mann, Barbara Alice (2001). Encyclopedia of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy). Greenwood Press. p. Intro – xiv. ISBN 0313308802. http://books.google.ca/books?id=zibNDBchPkMC&lpg=PP1&dq=the%20Iroquois%20Confederacy&pg=PR14#v=onepage&q&f=true. Retrieved 2010-04-15.

- ^ "The bison economy of the southern Alberta Plains". University of Calgary (The Applied History Research Group). 2007. http://www.ucalgary.ca/applied_history/tutor/calgary/bisoneconomy.html. Retrieved 2010-08-36.

- ^ a b BENGTSON, J.D (2008). "Materials for a Comparative Grammar of the Dene-Caucasian (Sino-Caucasian) Languages – In Aspects of Comparative Linguistics" (PDF). Moscow- RSUH. pp. v. 3, 45–118. http://starling.rinet.ru/Texts/dene_gr.pdf. Retrieved 2010-04-11.

- ^ a b c "First Nations – People of the Northwest Coast". B.C. Archives. 1999. http://www.bcarchives.gov.bc.ca/exhibits/timemach/galler07/frames/wc_peop.htm. Retrieved 2010-04-11.

- ^ McLay, Eric (2004). "Rediscovering the Coast Salish Cultural Landscape on Salt Spring Island". Salt Spring Island Archives. http://saltspringarchives.com/multicultural/firstnations/rediscovering.htm. Retrieved 2010-04-11.

- ^ "Archaeology in North America, Dorset Culture". Department of Anthropology, University of Waterloo. 2005. http://anthropology.uwaterloo.ca/ArcticArchStuff/dorset.html. Retrieved 2010-04-10.

- ^ McGhee, Robert (1999). "Nunavut – Ancient History". Museum of Civilization. http://www.nunavut.com/nunavut99/english/early.html. Retrieved 2010-04-10.

- ^ "Tirigusuusiit, Piqujait and Maligait: Inuit Perspectives on Traditional Law". Nunavut Arctic College. 1999. http://nac.nu.ca/OnlineBookSite/vol2/introduction.html. Retrieved 2010-08-28.

- ^ J. Sephton, (English, translation) (1880). "The Saga of Erik the Red". Icelandic Saga Database. http://sagadb.org/eiriks_saga_rauda.en. Retrieved 2010-08-11.

- ^ a b "Vikings: The North Atlantic Saga". National Museum of Natural History, Arctic Studies Center- (Smithsonian Institution). 2008. http://www.mnh.si.edu/vikings/voyage/subset/markland/history.html. Retrieved 2010-08-11.

- ^ Reeves, Arthur Middleton (2009). The Norse Discovery of America. BiblioLife. p. 191. http://books.google.ca/books?id=HkoPUdPM3V8C&pg=PA7&dq=The+Norse+discoverers+of+America,+the+Wineland+sagas#v=onepage&q&f=true. Retrieved 2010-04-15.

- ^ a b Pálsson, Hermann (1965). The Vinland sagas: the Norse discovery of America. Penguin Classics. p. 28. ISBN 0140441549. http://books.google.ca/books?id=m-4rb_GhQ5EC&lpg=PP1&dq=The%20Vinland%20sagas%3A%20the%20Norse%20discovery%20of%20America&pg=PA28#v=onepage&q&f=true. Retrieved 2010-04-15.

- ^ Diamond, Jared M (2006). Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail Or Succeed. Penguin Books. p. 207. ISBN 0143036556. http://books.google.ca/books?id=QyzHKSCYSmsC&lpg=PA207&dq=Vikings%20Settle%20Helluland%20Markland&pg=PA207#v=onepage&q&f=true. Retrieved 2010-04-16.

- ^ Haugen, Einar (Professor emeritus of Scandinavian Studies, Harvard University). "Was Vinland in Newfoundland?". (Originally published in "Proceedings of the Eighth Viking Congress, Arhus. August 24–31, 1977". Edited by Hans Bekker-Nielsen, Peter Foote, Olaf Olsen. Odense University Press. 1981. Archived from the original on 2001-05-15. http://web.archive.org/web/20010515202742/http://www.capecod.net/~nmgood/. Retrieved 2010-06-21.

- ^ Reeves, Arthur Middleton (2009). The Norse Discovery of America. BiblioLife. p. 82. http://books.google.ca/books?id=HkoPUdPM3V8C&pg=PA7&dq=The+Norse+discoverers+of+America,+the+Wineland+sagas#v=onepage&q&f=true. Retrieved 2010-04-15.

- ^ "L'Anse aux Meadows National Historic Site of Canada". Parks Canada. 2007. http://www.pc.gc.ca/lhn-nhs/nl/meadows/index_e.asp. Retrieved 2010-04-15.

- ^ "John Cabot's voyage of 1498". Memorial University of Newfoundland (Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage). 2000. http://www.heritage.nf.ca/exploration/cabot1498.html. Retrieved 2010-04-12.

- ^ Bailey W. Diffie and George D. Winius (1977). Foundations of the Portuguese empire. University of Minnesota Press. p. 464. ISBN 0816607826. http://books.google.ca/books?id=vtZtMBLJ7GgC&lpg=PA464&dq=The%20name%20%22Labrador%22%20and%20Jo%C3%A3o%20Fernandes%20Lavrador&pg=PA464#v=onepage&q&f=true. Retrieved 2010-08-13.

- ^ "CORTE-REAL, MIGUEL, Portuguese explorer". University of Toronto (Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online). 2000. http://www.biographi.ca/009004-119.01-e.php?&id_nbr=139. Retrieved 2010-04-12.

- ^ Diffie, Bailey W; Winius, George D (1977). Foundations of the Portuguese empire. University of Minnesota Press. pp. 464–465. ISBN 0816607826. http://books.google.ca/books?id=vtZtMBLJ7GgC&lpg=PA464&dq=The%20name%20%22Labrador%22%20and%20Jo%C3%A3o%20Fernandes%20Lavrador&pg=PA464#v=onepage&q&f=true. Retrieved 2010-08-13.

- ^ "PORTUGUESE BULLS, FIRST IN NORTH AMERICA". Dr. Manuel Luciano da Silva. 2000. http://www.dightonrock.com/pilgrim_chapter_11.htm. Retrieved 2010-04-12.

- ^ Freeman-Grenville (1975). Chronology of world history: a calendar of principal events from 3000 BC to... Rowman & Littlefield. p. 387. ISBN 0874717655.

- ^ Rompkey, Bill (2003). The story of Labrador. McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 20. ISBN 077352574. http://books.google.ca/books?id=JkwIotsOMUAC&lpg=PA20&dq=The%20name%20%22Labrador%22%20and%20Jo%C3%A3o%20Fernandes%20Lavrador&pg=PA20#v=onepage&q&f=true. Retrieved 2010-08-13.

- ^ "The Portuguese Explorers". Memorial University of Newfoundland. 2004. http://www.heritage.nf.ca/exploration/portuguese.html. Retrieved 2010-06-27.

- ^ a b "Port-Royal National Historic Site of Canada". Parks Canada (Government Of Canada). 2009. http://www.pc.gc.ca/eng/lhn-nhs/ns/portroyal/natcul/histor.aspx. Retrieved 2010-06-27.

- ^ "1524: The voyage of discoveries". Verrazzano Centre for Historical Studies. 2002. http://www.verrazzano.org/en/index2.php?c=viaggioscoperte. Retrieved 2010-11-10.

- ^ a b "Exploration — Jacques Cartier". The Historica Dominion Institute. http://www.histori.ca/minutes/minute.do?id=10123. Retrieved 2009-11-09.

- ^ a b c Riendeau, Roger E (2007). A brief history of Canada. Facts on File, cop. p. 36. ISBN 9780816063352. http://books.google.ca/books?id=CFWy0EfzlX0C&lpg=PA36&dq=In%201600%2C%20a%20trading%20post%20was%20established%20at%20%5B%5BTadoussac%2C%20Quebec%7CTadoussac%5D%5D%2C%20but%20only%20five%20settlers%20survived%20the%20winter.&pg=PA36#v=onepage&q&f=true. Retrieved 2010-08-11.

- ^ a b Vaugeois, Denis; Raymonde Litalien, Käthe Roth (2004). Champlain: The Birth of French America. Translated by Käthe Roth. McGill-Queen's Press. pp. 146, 242. ISBN 0773528504. http://books.google.com/books?id=ZnE0tjj9MbgC&pg=PA242&lpg=PA242&dq=%22Hendrick+Lonck%22. Retrieved 2010-06-20.

- ^ Champlain's journal: Entering 'The Lake Between' Joel Banner Baird. The Burlington Free Press (2009)

- ^ Hodge, Frederick Webb (2009). Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico, Volumes 2–4. Digital Scanning. p. 585. ISBN 1582187487. http://books.google.ca/books?id=68ERQ9fkyTMC&lpg=PA585&dq=Iroquois%20came%20into%20conflict%20with%20another%20Iroquoian%20people%2C%20the%20Wendat%2C%20known%20also%20as%20the%20'Hurons'&pg=PA585#v=onepage&q&f=true. Retrieved 2010-04-15.

- ^ Havard, Gilles; Aronoff, Phyllis; Scott, Howard (2001). The Great Peace of Montreal of 1701: French-native diplomacy. ISBN 0773522093. http://books.google.ca/books?id=YOQE3_sDJP0C&printsec=frontcover&dq=Great+Peace+of+Montreal#v=onepage&q&f=true. Retrieved 2010-06-23.

- ^ "Gilbert (Gylberte, Jilbert), Sir Humphrey". Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online. University of Toronto. May 2, 2005. http://www.biographi.ca/EN/ShowBio.asp?BioId=34374. Retrieved 2011-09-10.

- ^ Hornsby, Stephen J (2005). British Atlantic, American frontier : spaces of power in early modern British America. University Press of New England. pp. 14, 18–19, 22–23. ISBN 9781584654278.

- ^ a b Fry, Michael (2001). The Scottish Empire. Tuckwell Press. p. 21. ISBN 184158259X.

- ^ "Charles Fort National Historic Site of Canada". Parks Canada. 2009. http://www.pc.gc.ca/lhn-nhs/ns/charles/natcul/natcul3.aspx. Retrieved 2010-06-23.

- ^ Kingsford, William (2008 Volume 1). The history of Canada. BiblioLife. p. 109. ISBN 1147810478. http://books.google.ca/books?id=IBUwAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA109&lpg=PA109&dq=Treaty+of+Saint-Germain-en-Laye+%281632%29#v=onepage&q&f=true. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- ^ Powell, John (2005). Encyclopedia of North American immigration. Facts On File. p. 67. ISBN 0816046581. http://books.google.ca/books?id=VNCX6UsdZYkC&pg=PA67&dq=Trois-Rivi%C3%A8res+the+second+permanent+settlement+in+New+France#v=onepage&q&f=true. Retrieved 2010-10-10.

- ^ Shenwen, Li (2001). Stratégies missionnaires des Jésuites Français en Nouvelle-France et en Chine au XVIIieme siècle. Les Presses de l'Université Laval, L'Harmattan. p. 44. ISBN 2747511235.

- ^ Miquelon, Dale. "Ville-Marie (Colony)". The Canadian Encyclopedia. http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com/index.cfm?PgNm=TCE&Params=A1ARTA0008371. Retrieved 2010-06-23.

- ^ "(Census of 1665–1666) Role-playing Jean Talon". Statistics Canada. 2009. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/kits-trousses/jt2-eng.htm. Retrieved 2010-06-23.

- ^ "Statistics for the 1666 Census". Library and Archives Canada. 2006. http://amicus.collectionscanada.gc.ca/aaweb-bin/aamain/itemdisp?sessionKey=999999999_142&l=0&d=2&v=0&lvl=1&itm=30327415. Retrieved 2010-06-24.

- ^ "Estimated population of Canada, 1605 to present". Statistics Canada. 2009. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/98-187-x/4151287-eng.htm. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ^ Fuchs, Denise (2002-03) (Subcription required). Embattled Notions: Constructions of Rupert's Land's Native Sons, 1760 To 1861. Manitoba History. pp. (44): 10–17. 0226–5044. http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1G1-97059143.html.

- ^ "Our History: People". Hudson's Bay Company. http://www.hbc.com/hbcheritage/history/people/explorers/samuelhearne.asp. Retrieved 2007-11-14.

- ^ Marsh, James (1988). Troyes, Pierre de. The Canadian Encyclopedia. p. Volume 4, p.2196. http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com/index.cfm?PgNm=TCE&Params=A1ARTA0008139. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

- ^ Grenier, John (2008). The far reaches of empire: war in Nova Scotia, 1710–1760. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 21–30, 123–125. ISBN 9780806138763. http://books.google.ca/books?id=jVG5h6G5fWMC&pg=PA123&dq=Raid+on+Chignecto#v=onepage&q&f=true. Retrieved 2011-11-03.

- ^ Mark Zuehlke; C. Stuart Daniel (14 September 2006). Canadian Military Atlas: Four Centuries of Conflict from New France to Kosovo. Douglas & McIntyre. pp. 16–. ISBN 978-1-55365-209-0. http://books.google.com/books?id=KyNlm8SuplEC&pg=PA16. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- ^ John G. Reid (2004). The "conquest" of Acadia, 1710: imperial, colonial, and aboriginal constructions. University of Toronto Press. pp. 48–. ISBN 978-0-8020-8538-2. http://books.google.com/books?id=MqJ9qFqWK4IC&pg=PA48. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- ^ Alan Axelrod (23 April 2007). Blooding at Great Meadows: young George Washington and the battle that shaped the man. Running Press. pp. 62–. ISBN 978-0-7624-2769-7. http://books.google.com/books?id=7EBKOCt_P0EC&pg=PA62. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- ^ "History of Louisbourg". The Fortress Louisbourg Association. 2008. http://www.fortressoflouisbourg.ca/Overview/mid/12. Retrieved 2010-06-09.

- ^ John Fortier, Fortress of Louisbourg (Oxford University Press, 1979)

- ^ Raddall, Thomas H (1971). Halifax, Warden of the North. McClelland and Stewart Limited. pp. 18–21. ISBN 1551090600. http://www.ourroots.ca/page.aspx?id=1105466&qryID=56f6a64c-ac1e-45ad-85c1-f40e945f6a7e. Retrieved 2011-01-13.

- ^ John Grenier (2008). The far reaches of empire: war in Nova Scotia, 1710-1760. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 138–140. ISBN 978-0-8061-3876-3. http://books.google.com/books?id=jVG5h6G5fWMC&pg=PA138. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ^ Jobb, Dean (2005). The Acadians: A people's story of exile and triumph. Mississauga (Ont.): John Wiley & Sons Canada. p. 296. ISBN 0-470-83610-5. http://books.google.ca/books?id=bzksi8dKPCsC&lpg=PP1&dq=The%20Acadians%3A%20A%20people's%20story%20of%20exile%20and%20triumph%2C&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=true. Retrieved 2011-01-16.

- ^ a b c Lacoursière, Jacques (1995). Histoire populaire du Québec, Tome 1, des origines à 1791. Éditions du Septentrion, Québec. p. 270. ISBN 2-89448-050-4. http://books.google.ca/books?id=hbrS3bYEzKoC&lpg=PP1&dq=Histoire%20populaire%20du%20Qu%C3%A9bec%2C&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=true.

- ^ Mary Beacock Fryer (1993). More battlefields of Canada. Dundurn Press Ltd.. pp. 161–. ISBN 978-1-55002-189-9. http://books.google.com/books?id=543kHhH_ZYQC&pg=PA161. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ^ Helen Dewar, "Canada or Guadeloupe?: French and British Perceptions of Empire, 1760–1763," Canadian Historical Review, Dec 2010, Vol. 91 Issue 4, pp 637–660

- ^ "Original text of The Quebec Act of 1774". Canadiana (Library and Archives Canada). 2004 (1774). http://www.solon.org/Constitutions/Canada/English/PreConfederation/qa_1774.html. Retrieved 2010-04-11.

- ^ a b Maton, William F (1996). "The Royal Proclamation". The Solon Law Archive. http://www.solon.org/Constitutions/Canada/English/PreConfederation/rp_1763.html. Retrieved 2010-04-11.

- ^ a b McNaught, Kenneth (1976). The Pelican History of Canada. Pelican. p. 2d ed. 53. ISBN 0140210830.

- ^ Raddall, Thomas Head (2003). Halifax Warden of the North. McClelland and Stewart. p. 85. ISBN 1551090600.

- ^ "The expansion and final suppression of smuggling in Britain". Smuggling.co.uk. http://www.smuggling.co.uk/history_expansion.html. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- ^ "Territorial Evolution, 1867". Natural Resources Canada. 2010. http://atlas.nrcan.gc.ca/auth/english/maps/historical/territorialevolution/1867/1. Retrieved 2010-04-12.

- ^ Armstrong, Frederick H (1985). Handbook of Upper Canadian Chronology. Dundurn Press. ISBN 0-919670-92-X. http://books.google.ca/books?id=ZL9EJW4v2FYC&lpg=PA2&dq=Handbook%20of%20Upper%20Canadian%20Chronology&pg=PA2#v=onepage&q&f=true.

- ^ Landon, Fred (1941). Western Ontario and the American Frontier. Carleton University Press. pp. 17–22. ISBN 0771097344.

- ^ a b c Howard Jones (February 2002). Crucible of power: a history of American foreign relations to 1913. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-8420-2916-2. http://books.google.com/books?id=TFyLOUrdGFwC&pg=PA23. Retrieved 2011-09-17.

- ^ Timothy D. Willig (2008). Restoring the chain of friendship: British policy and the Indians of the Great Lakes, 1783–1815. U of Nebraska Press. pp. 243–44. ISBN 978-0-8032-4817-5. http://books.google.com/books?id=FtzyNOrEjY8C&pg=PP1. Retrieved 2011-09-17.

- ^ a b c d e Thompson, John Herd; Randall, Stephen J (2008). Canada and the United States: Ambivalent Allies. University of Georgia Press. pp. 19–24. ISBN 0820324035. http://books.google.ca/books?id=UVGHdmbzUTwC&lpg=PP1&dq=Canada%20and%20the%20United%20States%3A%20Ambivalent%20Allies&pg=PA19#v=onepage&q&f=true. Retrieved 2010-09-01.

- ^ Allen, Robert S (2009). "Tecumseh". The Canadian Encyclopedia. http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com/index.cfm?PgNm=TCE&Params=A1ARTA0007898. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

- ^ "Biography of Laura Secord". University of Toronto – Université Laval (from the Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online at Libraries and Archives Canada). 2000. http://www.warof1812.ca/laurasecord.htm. Retrieved 2010-06-21.

- ^ a b Gwyn, Richard (2008 Vol 1). Sir John A.: the Man Who Made Us. Random House of Canada Limited. ISBN 9780679314769. http://books.google.ca/books?id=CHs8qlWcl4gC&lpg=PP1&dq=Sir%20John%20A.%3A%20the%20Man%20Who%20Made%20Us%2C&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=true. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- ^ The 1837–1838 Rebellion in Lower Canada. McCord Museum's collections. 1999. accessdate 2006-12-10

- ^ a b Kyte, Elinor (1985). Redcoats and Patriotes, The Rebellions in Lower Canada. Canadian War Museum publication. p. 6. ISBN 0802069304. http://books.google.ca/books?id=MF8Im65MTqsC&lpg=PA297&dq=Redcoats%20and%20Patriots%2C%20The%20Rebellions%20in%20Lower%20Canada&pg=PA6#v=onepage&q&f=true.

- ^ a b "1839 – 1849, Union and Responsible Government". Canada in the Making project. 2005. http://www.canadiana.org/citm/themes/constitution/constitution11_e.html. Retrieved 2010-04-11.

- ^ R. D. Francis; Richard Jones, Donald B. Smith, R. D. Francis; Richard Jones; Donald B. Smith (February 2009). Journeys: A History of Canada. Cengage Learning. p. 147. ISBN 9780176442446. http://books.google.com/books?id=GbbZRIOKclsC&pg=PA147. Retrieved 2011-06-15.

- ^ Robert Lucas, Jr. (2003). "The Industrial Revolution". Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. http://www.minneapolisfed.org/pubs/region/04-05/essay.cfm. Retrieved 2007-11-14. "it is fairly clear that up to 1800 or maybe 1750, no society had experienced sustained growth in per capita income. (Eighteenth century population growth also averaged one-third of 1 percent, the same as production growth.) That is, up to about two centuries ago, per capita incomes in all societies were stagnated at around $400 to $800 per year."

- ^ McGowan, Mark (2009). Death or Canada: the Irish Famine Migration to Toronto 1847. Novalis Publishing Inc. p. 97. ISBN 2896461299.

- ^ Barman, Jean (1996). The West beyond the West: a history of British Columbia. University of Toronto Press. pp. 22–26. ISBN 0802071856. http://books.google.ca/books?id=_X_aK5pD5kgC&lpg=PA20&dq=Juan%20Jos%C3%A9%20P%C3%A9rez%20Hern%C3%A1ndez%20in%201774%20and%201775&pg=PA20#v=onepage&q&f=true. Retrieved 2010-04-12.

- ^ Lutz, John Sutton (2009). Makuk – A New History of Aboriginal-White Relations. University of British Columbia Press. p. 44. ISBN 0774811404. http://books.google.com/books?id=J2MNSaoAecIC&lpg=PP1&dq=makuk&pg=PA44#v=onepage&q&f=true. Retrieved 2010-04-16.

- ^ Ormsby, Margaret (1976). British Coumbia:a History. Macmillan. p. 33. ISBN 0758188137. http://www.questia.com/library/book/british-columbia-a-history-by-margaret-a-ormsby.jsp. Retrieved 2010-04-16.

- ^ "Our History". Hudson's Bay Company. 2009. http://www.hbc.com/hbc/history/. Retrieved 2010-04-16.

- ^ a b Barman, Jean (2007). The West Beyond the West-A History of British Columbia. University of Toronto Press. pp. 67–72. ISBN 0802071856. http://books.google.ca/books?id=_X_aK5pD5kgC&lpg=PA454&dq=The%20West%20Beyond%20the%20West-A%20History%20of%20British%20Columbia&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=true. Retrieved 2010-04-16.

- ^ a b LAC. "Canadian Confederation", in the Web site of Library and Archives Canada, 2006-01-09 (ISSN 1713-868X)

- ^ a b c d Andrew Heard (1990). "Canadian Independence". Simon Fraser University. http://www.sfu.ca/~aheard/324/Independence.html. Retrieved 2010-04-10.

- ^ Department of Canadian Heritage. "Ceremonial and Canadian Symbols Promotion > The crown in Canada". Queen's Printer for Canada. http://www.pch.gc.ca/pgm/ceem-cced/symbl/101/102-eng.cfm. Retrieved 2009-02-19.

- ^ The Royal Household. "The Queen and the Commonwealth > Queen and Canada". Queen's Printer. http://www.royal.gov.uk/MonarchAndCommonwealth/Canada/Canada.aspx. Retrieved 2009-05-14.

- ^ "Heritage Saint John > Canadian Heraldry". Heritage Resources of Saint John and New Brunswick Community College. http://www.saintjohn.nbcc.nb.ca/heritage/CorporateSeal/heraldry.htm. Retrieved 2009-07-03.

- ^ Romney, Paul (1999). Getting it Wrong: How Canadians Forgot Their Past and Imperiled Confederation. p. 78. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_7023/is_30/ai_n28817944/. Retrieved 2010-08-24.

- ^ a b "1867 – 1931: Territorial Expansion". Canadiana (Canada in the Making). 2009. http://www.canadiana.org/citm/themes/constitution/constitution14_e.html. Retrieved 2010-04-11.

- ^ a b c "The RCMP's History". Royal Canadian Mounted Police. 2009. http://www.rcmp-grc.gc.ca/hist/index-eng.htm. Retrieved 2010-04-12.

- ^ "What to Search: Topics-Canadian Genealogy Centre-Library and Archives Canada". Ethno-Cultural and Aboriginal Groups. Government of Canada. 2009-05-27. http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/genealogie/022-905.004-e.html. Retrieved 2009-10-02.

- ^ Boulton, Charles A. (1886) Reminiscences of the North-West Rebellions. Toronto. 2008. Retrieved 2010.

- ^ "Territorial evolution". Atlas of Canada. Natural Resources Canada. http://atlas.nrcan.gc.ca/site/english/maps/reference/anniversary_maps/terr_evol. Retrieved 2007-10-09.

- ^ "Canada: History". Country Profiles. Commonwealth Secretariat. http://www.thecommonwealth.org/YearbookInternal/145152/history/. Retrieved 2007-10-09.

- ^ D.M.L. FARR (2009). "Alaska Boundary Dispute". The Canadian Encyclopedia. http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com/index.cfm?PgNm=TCE&Params=A1ARTA0000107. Retrieved 2010-04-11.

- ^ Ian McKay, "The Liberal Order Framework: A Prospectus for a Reconnaissance of Canadian History" (2000)

- ^ Thompson, John Herd; Randall, Stephen J (2008). Canada and the United States: ambivalent allies. p. 79. ISBN 0820324035. http://books.google.ca/books?id=UVGHdmbzUTwC&lpg=PP1&dq=Canada%20and%20the%20United%20States%3A%20ambivalent%20allies&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=true.

- ^ Cook, Tim (1999), "'A Proper Slaughter': The March 1917 Gas Raid at Vimy" (PDF), Canadian Military History (Laurier Centre for Military Strategic and Disarmament Studies) 8 (2): 7–24, http://www.wlu.ca/lcmsds/cmh/back%20issues/CMH/volume%208/Issue%202/Cook%20-%20A%20Proper%20Slaughter%20-%20The%20March%201917%20Gas%20Attack%20at%20Vimy%20Ridge.pdf, retrieved 2010-04-10

- ^ Bashow, Lieutenant-Colonel David. "The Incomparable Billy Bishop: The Man and the Myths." Canadian Military Journal, Volume 3, Issue 4, Autumn 2002, pp. 55–60. Retrieved: September 1, 2008.

- ^ a b The War Office (1922). Statistics of the Military Effort of the British Empire During the Great War 1914–1920. Reprinted by Naval & Military Press. p. 237. ISBN 1847346812.

- ^ "The Conscription Crisis of 1917". Histori.ca. 1917-08-29. http://www.histori.ca/peace/page.do?pageID=278. Retrieved 2010-08-10.

- ^ "Military History: First World War: Homefront, 1917". Lermuseum.org. http://www.lermuseum.org/ler/mh/wwi/homefront1917.html. Retrieved 2010-08-10.

- ^ Canada and Québec: one country, two .... UBC Press. 1998. p. 52. ISBN 0774806532. http://books.google.ca/books?id=IftRWNt_0bcC&lpg=PA57&dq=Conscription%20Crisis%20of%201917%20%20Liberal%20party%20was%20deeply%20split&pg=PA57#v=onepage&q&f=true. Retrieved 2010-08-10.

- ^ Brown, Robert Craig; Cook, Ramsay (1974). Canada, 1896–1921 A Nation Transformed. McClelland & Stewart. p. ch 13. ISBN 0771022689.

- ^ "Canada and the League of Nations". Faculty.marianopolis.edu. 2007. http://faculty.marianopolis.edu/c.belanger/quebechistory/encyclopedia/LeagueofNation.htm. Retrieved 2010-08-10.

- ^ Bélanger, Claude (2001). "The Statute of Westminster". Marianopolis College. http://faculty.marianopolis.edu/c.belanger/quebechistory/federal/1931.htm. Retrieved 2010-04-10.

- ^ Norman Hillmer, Statute of Westminster: Canada's Declaration of Independence, Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ^ Robert Lewis, "The Workplace and Economic Crisis: Canadian Textile Firms, 1929–1935," Enterprise and Society Sept. 2009, Vol. 10 Issue 3, pp 498–528

- ^ "The On-to-Ottawa Trek". The University of Calgary (The Applied History Research Group). 1997. http://www.ucalgary.ca/applied_history/tutor/calgary/onottawa.html. Retrieved 2010-04-12.

- ^ "The Battle of the Atlantic" (PDF). Canadian Naval Review. 2005. http://naval.review.cfps.dal.ca/archive/1131599-7568616/vol1num1art5.pdf. Retrieved 2010-08-24.

- ^ Yesaki, Mitsuo (2003). Sutebusuton: a Japanese village on the British Columbia coast. Peninsula Pub. p. 122. ISBN 0968679935. http://books.google.ca/books?id=M_cxp_BgPmwC&lpg=PA122&dq=The%20Canadian%20mainland%20was%20also%20attacked%20when%20the%20Japanese%20submarine%20I-26%20shelled%20the%20Estevan%20Point%20lighthouse%20on%20Vancouver%20Island&pg=PA122#v=onepage&q&f=true. Retrieved 2010-08-24.

- ^ Francis, R D; Jones, Richard; Smith, Donald B (2009). Journeys: A History of Canada. Nelson Education. p. 428. ISBN 9780176442446. http://books.google.ca/books?id=GbbZRIOKclsC&lpg=PA428&dq=Conscription%20Crisis%20of%201944%20vs%201917&pg=PA428#v=onepage&q&f=true. Retrieved 2010-09-28.

- ^ Dolitsky, Alexander (2007). Allies in wartime: the Alaska-Siberia airway during World War II. Juneau, Alaska – Alaska-Siberia Research Center. p. 95. ISBN 9780965389167.