- Conservative Party of Canada

-

For the past party, see Conservative Party of Canada (1867–1942).

Conservative Party of Canada

Parti conservateur du Canada

Active federal partyLeader Stephen Harper President John Walsh Founded 2003 Headquarters #1204 - 130 Albert Street

Ottawa, Ontario

K1P 5G4Ideology Conservatism (Canadian)

Fiscal conservatismPolitical position Centre-right[1][2] International affiliation Asia Pacific Democrat Union

International Democrat Union[3]Official colours Blue Seats in the House of Commons 166 / 308Seats in the Senate 54 / 105Website www.conservative.ca Politics of Canada

Political parties

ElectionsThe Conservative Party of Canada (French: Parti conservateur du Canada), is a political party in Canada which was formed by the merger of the Canadian Alliance and the Progressive Conservative Party of Canada in 2003. It is positioned on the right of the Canadian political spectrum. The party came to power in the 2006 federal election as a minority government, a position it maintained after the 2008 election, before winning its first majority government in 2011. The current party leader is Stephen Harper, who has been the Prime Minister of Canada since 2006.

Contents

- 1 Principles and policies

- 2 History

- 3 Party leaders

- 4 Electoral results

- 5 Provincial parties

- 6 See also

- 7 References

- 8 External links

Principles and policies

The historical Conservative Party was founded by the United Empire Loyalists, and was vehemently opposed to free trade and further integration with the United States, aiming instead to model Canadian political institutions after British ones. Then under the leadership of Brian Mulroney, the party emphasized market forces in the economy and reached a landmark free-trade deal with the United States in 1988. The Conservative Party generally favours lower taxes, smaller government, more decentralization of federal government powers to the provinces, modeled after the Meech Lake Accord, and a tougher stand on "law and order" issues.

Parliamentary changes

As the successor of the western-based Canadian Alliance, the party also supports reform of the Senate to make it "elected, equal, and effective" (the "Triple-E Senate"). Party leader Stephen Harper advised the Governor General to appoint the unelected Michael Fortier to both the Senate and to the Cabinet on 6 February 2006, the day his minority government took office.[4] On 22 December 2008 Prime Minister Harper asked the Governor General to fill all eighteen Senate seats that had been vacant at the time. It was earlier reported in The Toronto Star that this action was "to kill any chance of a Liberal-NDP coalition government filling the vacancies next year".[5][6]

The party introduced a bill in the parliament to have fixed dates for elections and, with the support of the Liberals, passed it. However, Ned Franks, a Canadian parliamentary expert, maintains that the Prime Minister still has the right to advise the Governor General to dissolve the parliament early and drop the writs for an election.[7]

Abortion

The current Conservative government position on abortion is that a debate on abortion legislation will not take place in Parliament. Party leader Stephen Harper stated that "As long as I’m prime minister we are not reopening the abortion debate".[8]

The appointment of Dr. Henry Morgentaler, an abortion rights activist, to the prestigious Order of Canada, was deplored by some Conservative MPs. The Conservative government distanced itself from the award.[9]

The Conservative government excluded the funding of abortions in Canada's G8 health plan. Harper argued that he wanted to focus on non-divisive policies. This stance was opposed by the Liberals, NDP and international health and women's groups.[10] The Archbishop of Quebec and Primate of Canada, Marc Ouellet, praised this decision, but urged Harper to do more "in defence of the unborn".[11] In May 2010, 18 Conservative MPs addressed thousands of students at the pro-life 13th annual March for Life rally on Parliament Hill.[11]

Same-sex marriage

Party leader Stephen Harper staunchly opposes same-sex marriage. In 2005, Harper spoke at a pro traditional-marriage rally, and declared "we can win this fight".[12]

The party had a free vote on whether the House wanted to reopen the issue of same-sex marriage, which was defeated. In March 2011, just ahead of the expected Canadian election, the Conservatives added one line about gay rights to the "Discover Canada" booklet for new immigrants which they had published in 2009: "Canada’s diversity includes gay and lesbian Canadians, who enjoy the full protection of and equal treatment under the law, including access to civil marriage". The Minister of Citizenship, Immigration and Multiculturalism, Jason Kenney, had previously removed mention of gay rights from the booklet published in 2009.[13]

Deportations of Iraq War resisters

"Conscientious objectors" to "wars not sanctioned by the United Nations" should not be given a special "program" to "remain in Canada", according to all 110 Conservative Party MPs, who voted on this issue in the Parliament of Canada on 3 June 2008.[14][15][16] On 13 September 2008, this refusal to set up a “special program” was reiterated by a Conservative party spokeswoman after the first such conscientious objector (Robin Long) had been deported and sentenced to 15 months in jail.[17] This deportation occurred against the 3 June 2008 recommendation of a majority of elected representatives in Parliament.[14] (See details about two motions in Parliament concerning Canada and Iraq War Resisters.)

Crime and law enforcement

The Conservatives have promised to re-introduce Internet surveillance legislation that they were not able to pass, and bundle it with the rest of their crime bills. They said they plan to fast track the legislation within 100 days after taking office.[18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25]

History

Predecessors

The Conservative Party is political heir to a series of right-of-centre parties that have existed in Canada, beginning with the Liberal-Conservative Party founded in 1854 by Sir John A. Macdonald and Sir George-Étienne Cartier. The party later became known simply as the Conservative Party after 1873. Like its historical predecessors and conservative parties in some other Commonwealth nations (such as the Conservative Party of the United Kingdom), members of the present-day Conservative Party of Canada are sometimes referred to as "Tories". The modern Conservative Party of Canada is also legal heir to the heritage of the historical conservative parties by virtue of assuming the assets and liabilities of the former Progressive Conservative Party upon the merger of 2003.

The first incarnations of the Conservative Party in Canada were quite different from the Conservative Party of today, especially on economic issues. The early Conservatives were known to espouse economic protectionism and British imperialism, by emphasizing Canada's ties to the United Kingdom while vigorously opposing free trade with the United States; free trade being a policy which, at the time, had strong support from the ranks of the Liberal Party of Canada. The Conservatives also sparred with the Liberal Party due to its connections with French Canadian nationalists including Henri Bourassa who wanted Canada to distance itself from Britain, and demanded that Canada recognize that it had two nations, English Canada and French Canada, connected together through a common history. The Conservatives would go on with a popular slogan "one nation, one flag, one leader".[citation needed]

Progressive Conservative Party of Canada

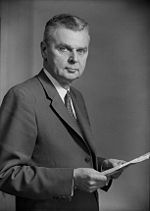

Prime Minister John Diefenbaker, leader of the PC Party from 1956 to 1967.

Prime Minister John Diefenbaker, leader of the PC Party from 1956 to 1967.

The Conservative Party's popular support waned (particularly in western Canada) during difficult economic times from the 1920s to 1940s, as it was seen by many in the west as an eastern establishment party which ignored the needs of the citizens of Western Canada. Westerners of multiple political convictions including small-"c" conservatives saw the party as being uninterested in the economically unstable Prairie regions of the west at the time and instead holding close ties with the business elite of Ontario and Quebec. As a result of western alienation both the dominant Conservative and Liberal parties were challenged in the west by the rise of a number of protest parties including the Progressive Party of Canada, the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), the Reconstruction Party of Canada and the Social Credit Party of Canada. The Progressives once outpaced the Conservatives, and, in 1920, became Official Opposition, though soon after, the Progressive Party folded. Its former leader John Bracken became leader of the Conservative Party in 1942 subject to several conditions, one of which was that the party be renamed the Progressive Conservative Party.[citation needed]

Meanwhile, many former supporters of the Progressive Conservative Party shifted their support to either the federal CCF or to the federal Liberals. The advancement of the provincially popular western-based conservative Social Credit Party in federal politics was stalled, in part by the strategic selection of leaders from the west by the Progressive Conservative Party. PC leaders such as John Diefenbaker and Joe Clark were seen by many westerners as viable challengers to the Liberals who traditionally had relied on the electorate in Quebec and Ontario for their power base. While none of the various protest parties ever succeeded in gaining significant power federally, they were damaging to the Progressive Conservative Party throughout its history, and allowed the federal Liberals to win election after election with strong urban support bases in Ontario and Quebec. This historical tendency earned the Liberals the unofficial title often given by some political pundits of being Canada's "natural governing party". Prior to 1984, Canada was seen as having a dominant-party system led by the Liberal Party while Progressive Conservative governments therefore were considered by many of these pundits as caretaker governments, doomed to fall once the collective mood of the electorate shifted and the federal Liberal Party eventually came back to power.[citation needed]

Prime Minister Brian Mulroney, leader of the Progressive Conservative Party from 1983 to 1993, helped move the party to endorse and initiate free trade with the United States.

Prime Minister Brian Mulroney, leader of the Progressive Conservative Party from 1983 to 1993, helped move the party to endorse and initiate free trade with the United States.

In 1984, the Progressive Conservative Party's electoral fortunes made a massive upturn under its new leader, Brian Mulroney, an anglophone Quebecer and former president of the Iron Ore Company of Canada, who mustered a large coalition of westerners aggravated over the National Energy Program of the Liberal government and Quebeckers who were angered over Quebec not having distinct status in the Constitution of Canada signed in 1982.[citation needed] This led to a huge landslide victory for the Progressive Conservative Party. Progressive Conservatives abandoned protectionism which the party had held strongly to in the past and which had aggravated westerners and businesses and fully espoused free trade with the United States and integrating Canada into a globalized economy. This was accomplished with the signing of the Canada-United States Free Trade Agreement (FTA) of 1989 and much of the key implementation process of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which added Mexico to the Canada-U.S. free trade zone.[citation needed]

Reform Party of Canada

In the late 1980s and 1990s, federal conservative politics became split by the creation of a new western-based protest party, the populist and social conservative Reform Party of Canada created by Preston Manning, son of Alberta Social Credit Premier Ernest Manning. It advocated deep decentralization of government power, abolition of official bilingualism and multiculturalism, democratization of the Canadian Senate, and suggested a potential return to capital punishment, and advocated significant privatization of public services.[citation needed] Westerners reportedly felt betrayed by the federal Progressive Conservative Party (PC), seeing it as catering to Quebec and urban Ontario interests over theirs. In 1989, Reform made headlines in the political scene when its first MP, Deborah Grey, was elected in a by-election in Alberta, which was a shock to the PCs which had almost complete electoral dominance over the province for years. Another defining event for western conservatives was when Mulroney accepted the results of an unofficial Senate "election" held in Alberta, which resulted in the appointment of a Reformer, Stanley Waters, to the Senate.[citation needed]

Preston Manning, Reform party founder and leader from 1987 to 2000.

Preston Manning, Reform party founder and leader from 1987 to 2000.

By the 1990s, Mulroney had failed to bring about Senate reform as he had promised (appointing a number of Senators in 1990). As well, social conservatives were dissatisfied with Mulroney's social progressivism. Canadians in general were furious with high unemployment, high debt and deficit, unpopular implementation of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) in 1991, and the failed constitutional reforms of the Meech Lake and Charlottetown accords. In 1993, support for the Progressive Conservative Party collapsed, and the party's representation in the House of Commons dropped from an absolute majority of seats to only two seats. The 1993 results were the worst electoral disaster in Canadian history, and the Progressive Conservatives never fully recovered.[citation needed]

In 1993, federal politics became divided regionally. The Liberal Party took Ontario, the Maritimes and the territories, the separatist Bloc Québécois took Quebec, while the Reform Party took Western Canada and became the dominant conservative party in Canada. The problem of the split on the right was accentuated by Canada's single member plurality electoral system, which resulted in numerous seats being won by the Liberal Party, even when the total number of votes cast for PC and Reform Party candidates was substantially in excess of the total number of votes cast for the Liberal candidate. Although this was a constant problem on the political left as well with the Liberals and NDP.[citation needed]

Merger

Rationale for the merger

With the right-wing vote split, the Liberal Party won three successive majority governments.[citation needed] This led the Reform Party, and subsequently the Canadian Alliance, as well as elements of the Progressive Conservative Party, to advocate "uniting the right".[citation needed]

Merger agreement

In 2003, the Canadian Alliance (formerly the Reform Party) and Progressive Conservative parties agreed to merge into the present-day Conservative Party, with the Alliance faction conceding its populist ideals and some social conservative elements.

On 15 October 2003, after closed-door meetings were held by the Canadian Alliance and Progressive Conservative Party, Stephen Harper (then the leader of the Canadian Alliance) and Peter MacKay (then the leader of the Progressive Conservatives) announced the "'Conservative Party Agreement-in-Principle", thereby merging their parties to create the new Conservative Party of Canada. After several months of talks between two teams of "emissaries", consisting of Don Mazankowski, Bill Davis and Loyola Hearn on behalf of the PCs and Ray Speaker Senator Gerry St. Germain and Scott Reid on behalf of the Alliance, the deal came to be.

On 5 December 2003 the Agreement-in-Principle was ratified by the membership of the Alliance by a margin of 96% to 4% in a national referendum conducted by postal ballot. On 6 December the PC Party held a series of regional conventions, at which delegates ratified the Agreement-in-Principle by a margin of 90% to 10%. On 7 December, the new party was officially registered with Elections Canada. On 20 March 2004, Harper was elected leader.

The merger was the culmination of the Canadian "Unite the Right" movement, driven by the desire to present an effective right-wing opposition to the Liberal Party of Canada, to create a new party that would draw support from all parts of Canada and would not split the right-wing vote. The splitting of the right-wing vote contributed to Liberal victories in the 1993 federal election, 1997 federal election and the 2000 election.[citation needed]

Opposition to the merger/defections

The merger process was opposed by some elements in both parties. In the PCs in particular, the merger process resulted in organized opposition, and in a substantial number of prominent members refusing to join the new party. The opponents of the merger were not internally united as a single internal opposition movement, and they did not announce their opposition at the same moment. The reasons for dissent varied. David Orchard argued that his written agreement with Peter MacKay, which had been signed a few months earlier at the 2003 Progressive Conservative Leadership convention, excluded any such merger. Orchard announced his opposition to the merger before negotiations with the Canadian Alliance had been completed. Over the course of the following year, Orchard led an unsuccessful legal challenge to the merger of the two parties.[citation needed]

In October and November, during the course of the PC party's process of ratifying the merger, four sitting Progressive Conservative MPs — André Bachand, John Herron, former Tory leadership candidate Scott Brison, and former Prime Minister Joe Clark — announced their intention not to join the new Conservative Party caucus, as did retiring PC Party president Bruck Easton. Clark and Brison argued that the party's merger with the Canadian Alliance drove it too far to the right, and away from its historical position in Canadian politics. Brison, at first, voted for and supported the ratification of the Alliance-Tory merger, then crossed the floor to the Liberals.[26] Soon afterward, he was made a parliamentary secretary in Paul Martin's Liberal government, and became a full cabinet minister after the 2004 federal election. Herron also ran as a Liberal candidate in the election, but did not join the Liberal caucus prior to the election. He lost his seat to the new Conservative Party's candidate Rob Moore. Bachand and Clark sat as independent Progressive Conservatives until an election was called in the spring of 2004, and then retired from Parliament.

On 14 January 2004, former Alliance leadership candidate Keith Martin, left the party, and sat temporarily as an independent. He was reelected, running as a Liberal, in the 2004 election, and again in 2006 and 2008. In the 38th Parliament (2004–05), Martin served as parliamentary secretary to Bill Graham, Canada's minister of defence. Additionally, three senators, William Doody, Norman Atkins, and Lowell Murray, declined to join the new party and continue to sit in the upper house as a rump caucus of Progressive Conservatives.

In February 2005, Liberals attempted to exacerbate the split among Tory Senators by appointing two anti-merger Progressive Conservatives, Nancy Ruth and Elaine McCoy, to the Senate. Both joined the rump PC Senate caucus. However, this gambit was not entirely successful: in March 2006, Senator Ruth joined the new Conservative Party and switched caucuses. In the early months following the merger, MP Rick Borotsik, who had been elected as Manitoba's only PC, became openly critical of the new party's leadership. Borotsik chose not to run in the 2004 general election. Finally, following the 2004 federal election, Conservative Senator Jean-Claude Rivest left the party to sit as an independent (choosing not to join Senators Doody, Atkins and Murray in their rump Progressive Conservative caucus). Senator Rivest cited, as his reason for this action, his concern that the new party was too right-wing and that it was insensitive to the needs and interests of Quebec.[citation needed]

Leadership election, 2004

Main article: Conservative Party of Canada leadership election, 2004In the immediate aftermath of the merger announcement, some Conservative activists hoped to recruit former Ontario Premier Mike Harris for the leadership. Harris declined the invitation, as did New Brunswick Premier Bernard Lord and Alberta Premier Ralph Klein. Outgoing Progressive Conservative leader Peter MacKay also announced he would not seek the leadership, as did former Democratic Representative Caucus leader Chuck Strahl. Jim Prentice, who had been a candidate in the 2003 PC leadership contest, entered the Conservative leadership race in mid-December but dropped out in mid-January due to an inability to raise funds so soon after his earlier leadership bid.

In the end, there were three candidates in the party’s first leadership election: former Canadian Alliance leader Stephen Harper, former Magna International CEO Belinda Stronach, and former Ontario provincial PC Cabinet minister Tony Clement. Voting took place on 20 March 2004. A total of 97,397 ballots were cast.[27] Harper won on the first ballot with a commanding 68.9% of the vote (67,143 votes). Stronach received 22.9% (22,286 votes), and Clement received 8.2% (7,968 votes).[28]

The vote was conducted using a weighted voting system in which all of Canada’s 308 ridings were given 100 points, regardless of the number of votes cast by party members in that riding (for a total of 30,800 points, with 15,401 points required to win). Each candidate would be awarded a number of points equivalent to the percentage of the votes they had won in that riding. For example, a candidate winning 50 votes in a riding in which the total number of votes cast was 100 would receive 50 points. A candidate would also receive 50 points for winning 500 votes in a riding where 1,000 votes were cast. In practice, there were wide differences in the number of votes cast in each riding across the country. More than 1,000 voters participated in each of the fifteen ridings with the highest voter turnout. By contrast, only eight votes were cast in each of the two ridings with the lowest levels of participation.)[29] As a result, individual votes in the ridings where the greatest numbers of votes were cast were worth less than one percent as much as votes from the ridings where the fewest votes were cast.[29]

The equal-weighting system gave Stronach a substantial advantage, because of the fact that her support was strongest in the parts of the country where the party had the fewest members, while Harper tended to win a higher percentage of the vote in ridings with larger membership numbers. Thus, the official count, which was based on points rather than on votes, gave her a much better result. Of 30,800 available points, Harper won 17,296, or 56.2%. Stronach won 10,613 points, or 34.5%. Clement won 2,887 points, or 9.4%.

The actual vote totals remained confidential when the leadership election results were announced; only the point totals were made public at the time, giving the impression of a race that was much closer than was actually the case. Three years later, Harper’s former campaign manager, Tom Flanagan, published the actual vote totals, noting that, among other distortions caused by the equal-weighting system, “a vote cast in Quebec was worth 19.6 times as much as a vote cast in Alberta.”[30]

2004 general election

Two months after Harper's election as national Tory leader, Liberal Party of Canada leader and Prime Minister Paul Martin called a general election for 28 June 2004. However, in the interim between the formation of the new party and the selection of its new leader, factional infighting and investigations into the Sponsorship Scandal significantly reduced the popularity of the governing Liberal Party.[citation needed]

This allowed the Conservatives to be more prepared for the race, unlike the 2000 federal election when few predicted the early election call. For the first time since the 1993 federal election, a Liberal government would have to deal with a united conservative front. The Liberals attempted to counter this with an early election call, as this would give the Conservatives less time to consolidate their merger. During the first half of the campaign, polls showed a rise in support for the new party, leading some pollsters to predict the election of a minority Conservative government. An unpopular provincial budget by Liberal Premier Dalton McGuinty hurt the federal Liberals' numbers in Ontario, as did a weak performance from Martin in the leaders' debates. The Liberals managed to narrow the gap and eventually regain momentum by targeting the Conservatives' credibility and motives, hurting their efforts to present a reasonable, responsible and moderate alternative to the governing Liberals.[citation needed]

Several controversial comments were made by Conservative MPs during the campaign. Early on in the campaign, Ontario MP Scott Reid indicated his feelings as Tory language critic that the policy of official bilingualism was unrealistic and needed to be reformed. Alberta MP Rob Merrifield suggested as Tory health critic that women ought to have mandatory family counseling before they choose to have an abortion. BC MP Randy White indicated his willingness near the end of the campaign to use the notwithstanding clause of the Canadian Constitution to override the Charter of Rights on the issue of same-sex marriage, and Cheryl Gallant, another Ontario MP, compared abortion to terrorism. The party was also criticized for issuing press releases accusing both Paul Martin and Jack Layton of supporting child pornography, although both releases were recalled within a few hours.

Harper's new Conservatives emerged from the election with a larger parliamentary caucus of 99 MPs while the Liberals were reduced to a minority government of 135 MPs, requiring the Liberals to obtain support from at least twenty-three opposition MPs in order to guarantee the passage of Liberal government legislation. The Conservatives' popular vote, however, was actually lower than the combined Alliance and PC popular vote in the 2000 federal election.[citation needed]

Founding convention: March 2005

In 2005, some political analysts such as former Progressive Conservative pollster Allan Gregg and Toronto Star columnist Chantal Hébert suggested that the then-subsequent election could result in a Conservative government if the public were to perceive the Tories as emerging from the party's founding convention (then scheduled for March 2005) with clearly defined, moderate policies with which to challenge the Liberals. The convention provided the public with an opportunity to see the Conservative Party in a new light, appearing to have reduced the focus on its controversial social conservative agenda (although most Conservatives continue to oppose same-sex marriage). It retained its populist appeal by espousing tax cuts, smaller government, a grassroots-oriented democratic reform, and more decentralization by giving the provinces more taxing powers and decision-making authority in joint federal-provincial programs. The party's law and order package was an effort to address the perception of rising homicide rates, which had gone up 12% in 2004.[31]

2006 general election

On 17 May 2005, MP Belinda Stronach unexpectedly crossed the floor from the Conservative Party to join the Liberal Party. In late August and early September 2005, the Tories released ads through Ontario's major television broadcasters that highlighted their policies towards health care, education and child support. The ads each featured Stephen Harper discussing policy with prominent members of his Shadow Cabinet. Some analysts suggested at the time that the Tories would use similar ads in the expected 2006 federal election, instead of focusing their attacks on allegations of corruption in the Liberal government as they did earlier on.

An Ipsos-Reid Poll conducted after the fallout from the first report of the Gomery Commission on the sponsorship scandal showed the Tories practically tied for public support with the governing Liberal Party,[32] and a poll from the Strategic Counsel suggested that the Conservatives were actually in the lead. However, polling two days later showed the Liberals had regained an 8-point lead.[33] On 24 November 2005, Opposition leader Stephen Harper introduced a motion of no confidence which was passed on 28 November 2005. With the confirmed backing of the other two opposition parties, this resulted in an election on 23 January 2006, following a campaign spanning the Christmas season.

The Conservatives started off the first month of the campaign by making a series of policy-per-day announcements, which included a Goods and Services Tax reduction and a child-care allowance. This strategy was a surprise to many in the news media, as they believed the party would focus on the sponsorship scandal; instead, the Conservative strategy was to let that issue ruminate with voters. The Liberals opted to hold their major announcements after the Christmas holidays; as a result, Harper dominated media coverage for the first few weeks of the campaign and was able "to define himself, rather than to let the Liberals define him". The Conservatives' announcements played to Harper's strengths as a policy wonk,[34] as opposed to the 2004 election and summer 2005 where he tried to overcome the perception that he was cool and aloof. Though his party showed only modest movement in the polls, Harper's personal approval numbers, which had always trailed his party's significantly, began to rise relatively rapidly.

On 27 December 2005, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police announced it was investigating Liberal Finance Minister Ralph Goodale's office for potentially engaging in insider trading before making an important announcement on the taxation of income trusts. The revelation of the criminal investigation and Goodale's refusal to step aside dominated news coverage for the following week, and it gained further attention when the United States Securities and Exchange Commission announced they would also launch a probe. The income trust scandal distracted public attention from the Liberals' key policy announcements and allowed the Conservatives to refocus on their previous attacks on corruption within the Liberal party. The Tories were leading in the polls by early January 2006, and made a major breakthrough in Quebec where they displaced the Liberals as the second place party (after the Bloc Québécois).[citation needed]

In response to the growing Conservative lead, the Liberals launched negative ads suggesting that Harper had a "hidden agenda", similar to the attacks made in the 2004 election. The Liberal ads did not have the same effect this time as the Conservatives had much more momentum, at one stage holding a ten-point lead. Harper's personal numbers continued to rise and polls found he was considered not only more trustworthy, but also a better potential Prime Minister than Paul Martin. In addition to the Conservatives being more disciplined, media coverage of the Conservatives was also more positive than in 2004. By contrast, the Liberals found themselves increasingly criticized for running a poor campaign and making numerous gaffes.[citation needed]

On 23 January 2006, the Conservatives won 124 seats, compared to 103 for the Liberals. The results made the Conservatives the largest party in the 308-member House of Commons, enabling them to form a minority government. On 6 February, Harper was sworn in as the 22nd Prime Minister of Canada, along with his Cabinet.

Further information: Canadian federal election, 2006Further information: Conservative Party candidates, 2006 Canadian federal electionFirst Harper Government (2006–08)

The Federal Accountability Act in response to the sponsorship scandal, President of the Treasury Board, the Honourable John Baird introduced the bill to the Canadian House of Commons on 11 April 2006. The bill was passed in the House of Commons on 22 June 2006, and was granted royal assent on 13 December 2006.

The 2006 Canadian federal budget was presented to the House of Commons by Finance Minister Jim Flaherty on 2 May 2006. The government announced that the Goods and Services Tax would be lowered from 7% to 6% (and eventually to 5%); income tax cuts for middle-income earners, and $1,200-per-child childcare payment (the "Universal Child Care Benefit") for Canadian parents. On 6 June 2006, the budget was introduced for third reading in the House of Commons and was declared passed by unanimous consent as the result of procedural confusion. (The Bloc Québécois had previously indicated that it would support the budget, and its passage was never in doubt.)

On 31 October 2006, Finance Minister Jim Flaherty announced that the government would begin taxing income trusts in 2011, which went against one of their campaign promises, causing much consternation among supporters. On 22 November 2006, Harper introduced his own motion to recognize the Québécois as forming a "nation within a united Canada". Five days later, Harper's motion passed, with a margin of 266–16; all federalist parties, as well as the Bloc Québécois, were formally behind it.[citation needed]

During three by-elections held on 17 September 2007, mayor Denis Lebel captured the seat of Roberval for the Conservatives, taking it from the Bloc, while Bernard Barre ran a close second in Saint-Hyacinthe-Bagot. This raised the Conservative total in the House of Commons to 126 members.Some believe these results indicate that the Conservatives have consolidated their position as the main federalist option in Quebec, outside of Montreal.[35][36]

The RCMP searched Conservative party headquarters in Ottawa on 15 April 2008 at the request of Elections Canada. Elections commissioner William Corbett requested the assistance of the Mounties. Elections Canada is probing Conservative party spending for advertisements during the 2006 parliamentary election campaign.[37]

The Conservative Party of Canada, having reached the $18.3 million advertising spending limit set out under the Canada Elections Act, transferred cash to 66 local campaign offices. The local campaigns sent the money back to national party headquarters to buy local television and radio advertisements for their candidates. Financial agents for at least 35 of those Conservative candidates later asked to be reimbursed for those expenses. Candidates who get 10% of the votes in their riding get a portion of their election expenses returned from Elections Canada. Elections Canada refused, saying the party paid for the ads, not the candidates. The Conservatives maintain they didn't break any rules.[38]

On 26 May 2008, the Conservative Party recognized in a private-members bill the 1932-33 famine in Ukraine as an act of genocide. The famine, orchestrated by Soviet dictator Josef Stalin, has been recognized as genocide by a dozen countries — although some historians disagree.[39]

2008 general election

On 7 September 2008 Stephen Harper asked the Governor General of Canada to dissolve parliament. The election took place on October 14. The Conservative Party returned to government with 143 seats, up from the 127 seats they held at dissolution, but short of the 155 necessary for a majority government. This is the third minority parliament in a row in Canada, and the second for Harper. The Conservative Party pitched the election as a choice between Harper and the Liberals' Stéphane Dion, whom they portrayed as a weak and ineffective leader. The election, however, was rocked midway through by the emerging global financial crisis and this became the central issue through to the end of the campaign. Harper has been criticised for appearing unresponsive and unsympathetic to the uncertainty Canadians were feeling during the period of financial turmoil, but he countered that the Conservatives were the best party to navigate Canada through the financial crisis, and portrayed the Liberal "Green Shift" plan as reckless and detrimental to Canada's economic well-being. The Conservative Party released its platform on October 7.[40] The platform states that it will re-introduce a bill similar to C-61.[41]

Second Harper Government (2008–11)

Some changes to Harper's cabinet were made on 30 October 2008.[42] On 4 December 2008, Harper asked Governor General Michaëlle Jean to prorogue Parliament in order to avoid a coalition of the Liberals and New Democratic Party taking power months after the 2008 election. The request was granted by Jean, and the prorogation lasted until 26 January 2009.

Policy convention: November 2008

The party’s second convention was held in Winnipeg in November 2008. This was the party's first convention since taking power in 2006, and media coverage concentrated on the fact that this time, the convention was not very policy-oriented, and showed the party to be becoming an establishment party. However, the results of voting at the convention reveal that the party’s populist side still had some life. A resolution that would have allowed the party president a director of the party’s fund was defeated because it also permitted the twelve directors of the fund to become unelected “ex-officio” delegates.[43] Some politically incorrect policy resolutions were debated, including one to encourage provinces to utilize “both the public and private health sectors”, but most of these were defeated.

Prorogation of Parliament 2008

Main article: 2008 Canadian political disputeAfter the Conservative Party released their economic statement on 27 November 2008, there was much criticism from Liberal Party, the NDP, and the Bloc Québécois. The opposition parties were against the cuts in public funding for political parties, reductions in pay equity, and reductions to the rights of public sector unions to strike, and they alleged that the Conservatives were not doing enough, and had no plan, to stimulate the weakening economy when the Finance Minister, Jim Flaherty, insisted that the government would "stay the course" and deliver a surplus budget in the coming year. As a result, these parties formed a coalition and planned to bring down the Conservative government through a non confidence vote. Prime Minister Harper asked the Governor General, Michaëlle Jean, to prorogue parliament to prevent the coming confidence vote. The Governor General granted this request 4 December; Parliament was prorogued until 26 January 2009. The subsequent backlash against the coalition temporarily propelled the Conservative polling numbers to majority territory, and resulted in the resignation of the Liberal leader Stephane Dion, the installation of Michael Ignatieff as interim-leader, and the Liberals backing away from support of a coalition.

Prorogation of Parliament 2009/2010

In a phone call to the Governor General on 30 December 2009, the Conservative Party under Stephen Harper requested the prorogation of parliament for the second time in slightly over a year, to last until March 2010. The request was granted.[44] In announcing prorogation to the public, the Prime Minister suggested that by suspending government operations, the country would be better able to enjoy the Vancouver Winter Olympics. Opposition parties disagreed, saying Harper sought the prorogation to avoid mounting pressure on his government over the Canadian Afghan detainee issue.[citation needed]

See also: 2010 Canada anti-prorogation protestsConservatives become largest party in the Senate

Prime Minister Harper filled five vacancies in the Senate of Canada with appointments of new Conservative senators on 29 January 2010. The appointments filled vacancies in Quebec, Newfoundland and Labrador, and New Brunswick, and two vacancies in Ontario. The new senators were Pierre-Hugues Boisvenu of Quebec, Bob Runciman of Ontario, Vim Kochhar of Ontario, Elizabeth Marshall of Newfoundland and Labrador, and Rose-May Poirier of New Brunswick. Throughout his time as Prime Minister, Harper has appointed a total of 38 Senators, all of which exclusively represent The Conservative Party of Canada.

This changed the party standings in the Senate, which had been dominated by Liberals, to 51 Conservatives, 49 Liberals, and five others. A Globe and Mail article has suggested Harper may invoke Section 26 of the Constitution, as his predecessor Brian Mulroney did during the GST debate, to have an extra eight senators appointed, for a total of 113, thus granting Tories an absolute majority in the Red Chamber.[45][46] With the 29 November 2010 retirement of former Liberal Senator Peter Stollery, Harper was in a position to appoint another Conservative Senator, bringing the Conservatives an absolute Senate majority with 53 of 105 seats. By the end of 2011 an additional four Liberals, a Progressive Conservative (not aligned with the Conservative Government), and one Conservative will reach the mandatory retirement age of 75.

Conservatives found in contempt of Parliament 2011

The Conservative government was defeated in a non-confidence vote on 25 March 2011, after being found in contempt of parliament, thus triggering a general election.[47] This was the first occurrence in Commonwealth history of a government in the Westminster parliamentary tradition losing the confidence of the House of Commons on the grounds of contempt of Parliament. The non-confidence motion was carried with a vote of 156 in favour of the motion, and 145 against.[48]

Third Harper Government (2011–present)

The Conservative party was elected with a majority government (166 seats) on 2 May 2011, the first time any party had won a majority since the Liberals in 2000 and the first time that a conservative party had a majority since the PC's in 1988

Party leaders

See also: Cabinet of Canada, Prime Minister of Canada, and List of Canadian Tory leaders and Tory Prime MinistersPicture Name Term start Term end Riding while leader Notes John Lynch-Staunton 8 December 2003 20 March 2004 Senate division of Grandville, Quebec Interim leader

Stephen Harper 20 March 2004 Calgary Southwest 22nd Prime Minister of Canada Electoral results

Conservative Party Federal Electoral Results Year Seats

in HouseConservative

candidatesSeats

wonSeat

ChangePopular

vote% of

popular

voteResult Conservative

leader2004 308 308 99 +99 3,994,682 29.62% Lib. minority government Harper 2006 308 308 124 +25 5,374,071 36.34% minority government Harper 2008 308 307 143 +19 5,205,334 37.6% minority government Harper 2011 308 307 166 +23 5,832,401 39.62% Majority government Harper Provincial parties

Main article: Conservative parties in CanadaThe Conservative Party, while officially having no current provincial wings, largely works with the former federal Progressive Conservative Party's provincial affiliates. There have been calls to change the names of the provincial parties from "Progressive Conservative" to "Conservative". However, there are other small "c" conservative parties with which the federal Conservative Party has close ties, such as the Saskatchewan Party, the Action démocratique du Québec (ADQ), and the British Columbia Liberal Party (not related to the federal Liberal Party of Canada). The federal Conservative party has the support of many of the provincial Conservative leaders. In Ontario, successive provincial PC Party leaders John Tory, Bob Runciman and Tim Hudak have expressed open support for Stephen Harper and the Conservative Party of Canada, with former Mike Harris cabinet members Jim Flaherty, Tony Clement, and John Baird now ministers in Harper's government.[citation needed]

Support between federal and provincial Conservatives is more tenuous in some other provinces. In Alberta, relations have been strained between the federal Conservative Party and the Progressive Conservatives. Part of the federal Tories' loss in the 2004 election was often blamed on then Premier Klein's public musings on health care late in the campaign. Klein had also called for a referendum on same-sex marriage. With the impending 2006 election, Klein predicted another Liberal minority, though this time the federal Conservatives won a minority government. Klein's successor Ed Stelmach has generally tried to avoid causing similar controversies, however Harper's surprise pledge to restrict bitumen exports drew a sharp rebuke from the Albertan government, who warned such restrictions would violate both the Constitution of Canada and the North American Free Trade Agreement. After the 2007 budget was announced the two conservative governments in Nova Scotia and Newfoundland and Labrador accused the federal Conservatives of breaching the terms of the Atlantic Accord.[citation needed]

As a result relations have worsened between the two provincial governments, leading Newfoundland and Labrador Premier Danny Williams to publicly denounce the federal Conservatives, which has given rise to his ABC (Anything But Conservative) campaign in the 2008 election. While officially separate, federal Conservative Party documents, such as membership applications, can be picked up from most provincial Progressive Conservative Party offices. Several of the provincial parties also contain open links to the federal Conservative website on their respective websites.[citation needed]

See also

See also: List of political parties in CanadaReferences

- ^ "Canada 2011". Political Compass. http://politicalcompass.org/canada2011. Retrieved 21 April 2011.

- ^ "FACTBOX-Canada's political parties as election looms". Reuters. 23 March 2011. http://www.reuters.com/article/2011/03/23/canada-politics-parties-idUSN2329368320110323.

- ^ IDU.org

- ^ [1], CTV News, 7 February 2006

- ^ Bruce campion-smith Ottawa bureau chief (11 December 2008). "Harper set to name 18 to Senate". Toronto: thestar.com. http://www.thestar.com/news/canada/article/552046. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ CTV News (2008-09-12). "Harper to fill 18 Senate seats with Tory loyalists". Ctv.ca. http://www.ctv.ca/servlet/ArticleNews/story/CTVNews/20081210/harper_senate_081210.

- ^ "PM can override fixed-date vote: expert". Ottawa Citizen. 9 April 2008. http://www.canada.com/ottawacitizen/news/story.html?id=15c68d91-edff-467f-9045-6f8c44c631d3.

- ^ "Harper says he won't reopen abortion debate". CBC News. 21 April 2011. http://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/canadavotes2011/story/2011/04/21/cv-election-parenthood-042111.html#.

- ^ "Morgentaler 'honoured' by Order of Canada; federal government 'not involved'". CBC News. 2 July 2008. http://www.cbc.ca/canada/story/2008/07/02/morgentaler-reax.html#ixzz121c0mPs2.

- ^ "Maternal plan should unite Canadians: Harper". CBC News. 27 April 2010. http://www.cbc.ca/health/story/2010/04/27/maternal-health-harper.html.

- ^ a b "Anti-abortion activists praise Harper's maternal-health stand". Toronto: The Globe and Mail. 13 May 2010. http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/politics/anti-abortion-activists-praise-harpers-maternal-health-stand/article1568191.

- ^ "Canada's Evangelical movement: political awakening". CBC News. 13 June 2005. http://www.cbc.ca/news/background/evangelical.

- ^ "Citizenship guide gets single sentence on gay rights". 14 March 2011. http://www.ctv.ca/CTVNews/Canada/20110314/citizenship-guide-110314. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- ^ a b Smith, Joanna (3 June 2008). "MPs vote to give asylum to U.S. military deserters". The Toronto Star. http://www.thestar.com/News/Canada/article/436575. Retrieved 19 July 2008.

- ^ "Report — Iraq War Resisters/Rapport –Opposants à la guerre en Irak". House of Commons/Chambre des Communes, Ottawa, Canada. http://cmte.parl.gc.ca/cmte/CommitteePublication.aspx?SourceId=222011. Retrieved 9 June 2008.

- ^ "Official Report * Table of Contents * Number 104 (Official Version)". House of Commons/Chambre des Communes, Ottawa, Canada. http://www2.parl.gc.ca/HousePublications/Publication.aspx?Language=E&Mode=1&Parl=39&Ses=2&DocId=3543213#Int-2506938. Retrieved 9 June 2008.

- ^ Kyonka, Nick (23 August 2008). "Iraq war resister sentenced to 15 months". Toronto Star. http://www.thestar.com/article/484115. Retrieved 13 September 2008.

- ^ "Canadian conservatives promise "big brother laws": at least they are honest". TechEye. 11 April 2011. http://www.techeye.net/security/canadian-conservatives-promise-big-brother-laws. Retrieved 17 April 1011.

- ^ "Michael Geist – The Conservatives Commitment to Internet Surveillance". Michaelgeist.ca. 9 April 2011. http://www.michaelgeist.ca/content/view/5733/125. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ^ "Electronic snooping bill a 'data grab': privacy advocates". CBC News. 19 June 2009. http://www.cbc.ca/technology/story/2009/06/19/tech-internet-communications-electronic-police-bills-surveillance-follo-privacy.html.

- ^ "New Canadian legislation will give police greater powers". Digitaljournal.com. 21 June 2009. http://www.digitaljournal.com/article/274527. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ^ "ISPs must help police snoop on internet under new bill". CBC News. 18 June 2009. http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/story/2009/06/18/tech-internet-police-bill-intercept-electronic-communications.html.

- ^ Matt Hartley and Omar El Akkad (18 June 2009). "Tories seek to widen police access online". The Globe and Mail. http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/technology/tories-seek-to-widen-police-access-online/article1187507. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ^ Canadian bill forces personal data from ISPs sans warrant – http://www.theregister.co.uk/2009/06/18/canada_isp_intercept_bills/

- ^ Brown, Jesse (13 April 2011). "Harper's promise: a warrantless online surveillance state: Why ‘lawful access’ legislation is on its way and why that should worry you". Macleans.ca. http://www2.macleans.ca/2011/04/13/harpers-promise-a-warrantless-online-surveillance-state/. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ^ "MacKay slams Brison for joining the Liberals". CBC.ca. 2003-12-10. http://www.cbc.ca/news/story/2003/12/10/brison_031210.html. Retrieved 2011-03-28.

- ^ Tom Flanagan, Harper’s Team. Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2007, pg. 131

- ^ Tom Flanagan, Harper's Team. Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2007, pg. 133

- ^ a b Tom Flanagan, Harper's Team. Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2007, pg. 135

- ^ Tom Flanagan, Harper’s Team. Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2007, pg. 134

- ^ "Statistics Canada re spike in homicides". Statcan.ca. 2005-07-21. http://www.statcan.ca/Daily/English/050721/d050721a.htm. Retrieved 2011-05-05.

- ^ "Grits Thrashed In Wake Of Gomery Report". Ipsos-na.com. 2005-11-04. http://www.ipsos-na.com/news/pressrelease.cfm?id=2857. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ^ "Canada Federal Election 2010 Public Opinion Polls National Election Almanac". Electionalmanac.com. http://www.electionalmanac.com/canada/polls.php. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ^ "andrewcoyne.com". Web.archive.org. Archived from the original on 2006-11-16. http://web.archive.org/web/20061116022016/http://andrewcoyne.com/Essays/Newspapers/Campaign_strategies.html. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ^ Gazette, The (8 September 2007). "The by-election blues". Canada.com. http://www.canada.com/montrealgazette/story.html?id=475783f1-664b-4acc-b118-1d75d22fd344&p=2. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ Woods, Allan (18 September 2007). "Liberals trounced in Quebec by-elections". Toronto: thestar.com. http://www.thestar.com/News/article/257720. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ "RCMP raid Conservative party headquarters over election matter". The Canadian Press. http://canadianpress.google.com/article/ALeqM5hxnGmWfP075hJVk25I6xUpzatDSA. Retrieved 2008-04-15.

- ^ "Mounties search Tory headquarters". CBC.ca. 15 April 2008. http://www.cbc.ca/canada/ottawa/story/2008/04/15/rcmp-tories.html. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ "Yushchenko thanks Harper for support in NATO bid". CTV.ca. 26 May 2008. http://www.ctv.ca/servlet/ArticleNews/story/CTVNews/20080526/Ukrainian_Yushchenko_080526/20080526?hub=TopStories. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ "Canada Votes - Reality Check - The Conservative platform". CBC.ca. http://www.cbc.ca/news/canadavotes/realitycheck/2008/10/the_conservative_platform.html. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ^ "CBC News - Technology & Science - Conservatives pledge to reintroduce copyright reform". CBC.ca. 2008-10-07. http://www.cbc.ca/technology/story/2008/10/07/tech-conservatives.html. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ^ Canada (30 October 2008). "Shuffle reflects No. 1 priority: the economy". Toronto: The Globe and Mail. http://www.theglobeandmail.com/servlet/story/RTGAM.20081030.wcabinetn1030/BNStory/politics/home?cid=al_gam_mostview. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ "Convention Watch: 2008". Blog.macleans.ca. 15 November 2008. http://blog.macleans.ca/tag/cpc-conventionwatch-2008. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ News Service, Canwest (24 January 2010). "Thousands turn out at rallies to protest proroguing of Parliament". Canwest Publishing Inc (The Montreal Gazette). http://www.montrealgazette.com/technology/Thousands+turn+rallies+protest+proroguing+Parliament/2477360/story.html. Retrieved 28 January 2010.

- ^ The CBC, 3 January 2010, by Kady O'Malley.

- ^ "UPDATED: Sunday SenateWatch: Five vacancies? Why not a baker's dozen instead?". CBC. http://www.cbc.ca/politics/insidepolitics/2010/01/sunday-senatewatch-five-vacancies-why-not-a-bakers-dozen-instead.html.

- ^ "Government's defeat sets up election call". CBC News. 25 March 2011. http://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/story/2011/03/25/pol-defeat.html.

- ^ "Official Report * Table of Contents * Number 149 (Official Version)". .parl.gc.ca. http://www2.parl.gc.ca/HousePublications/Publication.aspx?Language=E&Mode=1&Parl=40&Ses=3&DocId=5072532#Div-204. Retrieved 2011-05-05.

External links

- Conservative Party of Canada official website

- Conservative Party of Canada's channel on YouTube

- Conservative Party of Canada — 2006 Election Platform

Conservative and right-of-centre parties in Canada Forming the government Conservative Party of Canada - British Columbia Liberals - Alberta PCs - New Brunswick PCs - Newfoundland and Labrador PCs - Saskatchewan Party - Yukon PartyForming the official opposition Third Parties with representation Action démocratique du Québec - Nova Scotia PCs - Alberta Wildrose PartyNo representation in the Commons No representation in legislature British Columbia Conservatives - Family Coalition (Ontario) - Saskatchewan PCs - Social Credit (Alberta) - Social Credit (British Columbia) - Reform (Ontario)Historical national parties Historical provincial and territorial parties Alberta Alliance - Quebec Conservatives - New Brunswick Confederation of Regions Party - Northwest Territories Liberal-Conservatives - Ralliement créditiste du Québec - Union Nationale - Yukon Progressive Conservative PartyLeaders of the Conservative Party of Canada and its antecedents Liberal-Conservative (1867–1873) Conservative (1873–1942) Progressive Conservative (1942–2003) Reform (1987–2000) Canadian Alliance (2000–2003) Conservative (2003–present) Federal political parties in Canada House of Commons Senate Other parties recognized

by Elections CanadaNotable historical parties Anti-Confederate · Bloc populaire · Canadian Alliance · Conservative (historical) · Co-operative Commonwealth · Labour · Labour-Progressive · New Democracy · Progressive Conservative · Progressive/United Farmers · Ralliement créditiste · Reform · Rhinoceros (historical) · Social Credit · UnionistStephen Harper Prime Ministership Prime Ministership of Stephen Harper · Cabinet: 28th Canadian Ministry · Parliaments: 39th Canadian parliament, 40th Canadian parliament, 41st Canadian Parliament · Party: Conservative Party of CanadaPolicies Legislation 2006 budget · 2007 budget · 2008 budget · 2009 budget · 2010 budget · 2011 budget · Federal Accountability Act · Québécois nation motion · Veterans' Bill of RightsElections Related 2004 Conservative Party leadership election · "Canada's New Government" · War in Afghanistan · 2008–2009 Canadian parliamentary disputeFamily Categories:- Conservative Party of Canada

- Federal political parties in Canada

- International Democrat Union member parties

- Organizations based in Ottawa

- Political parties established in 2003

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.