- Immigration to Canada

-

Immigration to Canada

This article is part of a series Topics Canadians

History of immigration

Economic impact of immigration

Population by year

Ethnic origins

Immigration department

Passport Canada

Permanent Resident CardNationality law History of nationality law

Citizenship Act 1946

Immigration Act, 1976

Immigration Protection Act

Citizenship Test

Oath of CitizenshipCitizenship classes Permanent resident

Honorary citizenship

Commonwealth citizen

Temporary resident

Refugee

Lost Canadians

"Canadians of convenience"Demographics of Canada Immigration to Canada is the process by which people migrate to Canada to reside permanently in the country. The majority of these individuals become Canadian citizens. After 1947, domestic immigration law and policy went through major changes, most notably with the Immigration Act, 1976, and the current Immigration and Refugee Protection Act from 2002. Canadian immigration policies are still evolving. As recent as in 2008, Citizenship and Immigration Canada has made significant changes to streamline the steady flow of immigrants. The changes included reduced professional categories for skilled immigration as well as caps for immigrants in various categories.

In Canada there are four categories of immigrants: family class (closely related persons of Canadian residents living in Canada), economic immigrants (skilled workers and business people), other (people accepted as immigrants for humanitarian or compassionate reasons) and refugees (people who are escaping persecution, torture or cruel and unusual punishment).

Currently, Canada is known as a country with a broad immigration policy which is reflected in Canada's ethnic diversity. According to the 2001 census by Statistics Canada, Canada has 34 ethnic groups with at least one hundred thousand members each, of which 10 have over 1,000,000 people and numerous others represented in smaller amounts. 16.2% of the population belonged to visible minorities: most numerous among these are South Asian (4.0% of the population), Chinese (3.9%), Black descent (2.5%), and Filipino (1.1%). Other than Canadians of British, Irish, or French descent there are more members of Ethnic groups not classified as visible minorities than this 16.2%; the largest are: German (10.18%), and Italian (4.63%), with 3.87% being Ukrainian (some estimates placed them at 4 to 5%)[citation needed] - the largest Ukrainian community outside Ukraine[citation needed], 3.87% being Dutch, and 3.15% being Polish. Other minority ethnic origins include Russian (1.60%), Norwegian (1.38%), Portuguese (1.32%), and Swedish (1.07%).[1] ("North American Indians", a group which may include migrants of indigenous origin from the United States and Mexico but which for the most part are not considered immigrants, comprise 4.01% of the national population.)[1]

Contents

History

Main articles: History of immigration to Canada and History of Canadian nationality law Immigration and Births in Canada from 1850 to 2000[2]

Immigration and Births in Canada from 1850 to 2000[2]

After the initial period of British and French colonization, four major waves (or peaks) of immigration and settlement of non-aboriginal peoples took place over a period of almost two centuries. The fifth wave is currently ongoing.

First wave

The first wave of significant, non-aboriginal immigration to Canada occurred over almost two centuries with slow but progressive French settlement of Quebec and Acadia with smaller numbers of American and European entrepreneurs in addition to British military personnel. This wave culminated with the influx of British Loyalists fleeing the American Revolution, chiefly from the Mid-Atlantic States mostly into what is today Southern Ontario, the Eastern Townships of Quebec, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. Scottish Highlanders from land clearances also became land owners in Canada during this period.

Second wave

The second wave from Britain and Ireland was encouraged to settle in Canada after the War of 1812, and included British army regulars who had served in the war. The colonial governors of Canada, who were worried about another American invasion attempt and to counter the French-speaking influence of Quebec, rushed to promote settlement in back country areas along newly constructed plank roads within organized land tracts, mostly in Upper Canada (present-day Ontario). With the second wave Irish immigration to Canada had been increasing and peaked when the Irish Potato Famine occurred from 1846 to 1849 resulting in hundreds of thousands more Irish arriving on Canada's shores, although a significant portion migrated to the United States either in the short-term or over the subsequent decades.

The Dominion Lands Act of 1872 copied the American system by offering ownership of 160 acres of land free (except for a small registration fee) to any man over 18 or any woman heading a household. They need not be citizens, but had to live on the plot and improve it.

Clifford Sifton, minister of the Interior in Ottawa, 1896-1905, argued that the free western lands were ideal for growing wheat and would attract large numbers of hard-working farmers. He removed obstacles that included control of the lands by companies or organizations that did little to encourage settlement. Land companies, the Hudson's Bay Company, and school lands all accounted for large tracts of excellent land. The railways kept closed even larger tracts because they were reluctant to take legal title to the even-numbered lands they were due, thus blocking sale of odd-numbered tracts. Sifton broke the legal logjam, and set up aggressive advertising campaigns in the U.S. and Europe, with a host of agents promoting the Canadian west. He also brokered deals with ethnic groups that wanted large tracts for homogeneous settlement. His goal was to maximize immigration from Britain, eastern Canada and the U.S.[3]

Third wave

The third wave of immigration coming mostly from continental Europe peaked prior to World War I, between 1911–1913 (over 400,000 in 1913) and the fourth wave also from that same continent in 1957 (282,000), making Canada a more multicultural country with substantial non-English or -French speaking populations. For example, Ukrainian Canadians account for the largest Ukrainian population outside Ukraine and Russia. Periods of lowered immigration have also occurred, especially during the First World War and the Second World War, in addition to the Great Depression.

Come to Stay, printed in 1880 in the Canadian Illustrated News, which refers to immigration to the "Dominion".

Come to Stay, printed in 1880 in the Canadian Illustrated News, which refers to immigration to the "Dominion".

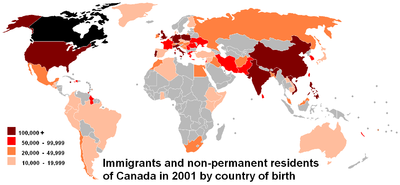

Immigration since the 1970s has overwhelmingly been of visible minorities from the developing world. This was largely influenced in 1967 when the Immigration Act was revised and this continued to be official government policy. During the Mulroney government, immigration levels were increased. By the late 1980s, the fifth wave of immigration has maintained with slight fluctuations since (225,000–275,000 annually). Currently, most immigrants come from South Asia and China and this trend is expected to continue.

Chinese

Prior to 1885, restrictions on immigration were imposed mostly in response to large waves of immigration rather than planned policy decisions, but not specifically targeted at one group or ethnicity, at least as official policy. Then came the introduction of the first Chinese Head Tax legislation passed in 1885, which was in response to a growing number of Chinese working on the Canadian Pacific Railway. Subsequent increases in the head tax in 1900 and 1903 limited Chinese entrants to Canada. In 1923 the government passed the Chinese Immigration Act which excluded Chinese from entering Canada altogether between 1923 and 1947. For discriminating against Chinese immigrants in past periods, an official government apology and compensations were announced on 22 June 2006.

Citizenship

Canadian citizenship was originally created under the Immigration Act, 1910, to designate those British subjects who were domiciled in Canada. All other British subjects required permission to land. A separate status of "Canadian national" was created under the Canadian Nationals Act, 1921, which was defined as being a Canadian citizen as defined above, their wives, and any children (fathered by such citizens) that had not yet landed in Canada. After the passage of the Statute of Westminster in 1931, the monarchy thus ceased to be an exclusively British institution. Because of this Canadians, and others living in countries that became known as Commonwealth realms, were known as subjects of the Crown. However in legal documents the term "British subject" continued to be used.

Canada was the first nation in the then British Commonwealth to establish its own nationality law in 1946, with the enactment of the Canadian Citizenship Act 1946. This took effect on January 1st 1947. In order to acquire Canadian citizenship on January 1st 1947, one generally had to be a British subject on that date, an Indian or Eskimo, or had been admitted to Canada as landed immigrants before that date. The phrase British subject refers in general to anyone from the United Kingdom, its colonies at the time, or a Commonwealth country. Acquisition and loss of British subject status before 1947 was determined by United Kingdom law (see History of British nationality law).

On 15 February 1977, Canada removed restrictions on dual citizenship. Many of the provisions to acquire or lose Canadian citizenship that existed under the 1946 legislation were repealed. Canadian citizens are in general no longer subject to involuntary loss of citizenship, barring revocation on the grounds of immigration fraud.

Statistics Canada has tabulated the effect of immigration on population growth in Canada from 1851 to 2001.[2]

Out-migration

Out migration from Canada to the United States has historically exceeded in-migration but there were short periods where the reverse was true; for example, the Loyalist refugees; during the Cariboo/Fraser Gold Rush and later the Klondike Gold Rush which saw many American prospectors inhabiting British Columbia and the Yukon; land settlers moving from the Northern Plains to the Prairies in the early 20th century and also during periods of political turmoil and/or during wars, for example the Vietnam War.

Scottish immigration to Canada

One of the largest groups to immigrate to Canada were the Scottish. Nearly 5 million Canadians claim Scottish heritage. The first Canadian Prime Minister John A. Macdonald, who is widely regarded as the chief Father of Canadian Confederation, was a Scot from Glasgow. His successor, Alexander Mackenzie, was also born in Scotland. The Scottish culture is without a doubt linked with that of the Canadian. There are over five Canadian military regiments which share the name with famous Scottish regiments such as the Scottish Black Watch, Gordon Highlanders and the King's Own Scottish Borderers. Scots were also numerous and prominent amongst Quebec's business elite. The Province of Nova Scotia (New Scotland), New Brunswick, Manitoba and Ontario was where the majority of Scots settled.

Immigration rate

In 2001, 250,640 people immigrated to Canada, relative to a total population of 30,007,094 people per the 2001 Census. On a compounded basis, that immigration rate represents 8.7% population growth over 10 years, or 23.1% over 25 years (or 6.9 million people). Since 2001, immigration has ranged between 221,352 and 262,236 immigrants per annum.[4] According to Canada's Immigration Program (October 2004) Canada has the highest per capita immigration rate in the world,[5] although statistics in the CIA World Factbook show that a number of city states and small island nations, as well as some larger countries in regions with refugee movements, have higher per capita rates.[6] The three main official reasons given for the high level of immigration are:

- The social component – Canada facilitates family reunification.

- The humanitarian component – Relating to refugees.

- The economic component – Attracting immigrants who will contribute economically and fill labour market needs (See related article, Economic impact of immigration to Canada).

The level of immigration peaked in 1993 in the last year of the Progressive Conservative government and was maintained by Liberal Party of Canada. Ambitious targets of an annual 1% per capita immigration rate were hampered by financial constraints. The Liberals committed to raising actual immigration levels further in 2005. All political parties are now cautious about criticizing the high level of immigration.

Immigrant population growth is concentrated in or near large cities (particularly Vancouver, Toronto, and Montreal). These cities are experiencing increased services demands that accompany strong population growth, causing concern about the capability of infrastructure in those cities to handle the influx. For example, a Toronto Star article published on 14 July 2006 authored by Daniel Stoffman noted that 43% of immigrants move to the Greater Toronto Area and said "unless Canada cuts immigrant numbers, our major cities will not be able to maintain their social and physical infrastructures".[7] Most of the provinces that do not have one of those destination cities have implemented strategies to try to boost their share of immigration.

According to Citizenship and Immigration Canada, under the Canada-Quebec Accord, Quebec has sole responsibility for selecting most immigrants destined to the province. Quebec has been admitting about the same number of immigrants as the number choosing to immigrate to British Columbia even though its population is almost twice as large.[8]

Statistics Canada projects that, by 2031, almost one-half of the population over the age of 15 will be foreign-born or have at least one foreign-born parent.[9] The number of visible minorities will double and make up the majority of the population of cities in Canada.[10]

Immigration categories

There are three main categories to Canadian immigration:

- Economic immigrants

- Citizenship and Immigration Canada uses several sub-categories of economic immigrants. The high-profile Skilled worker principal applicants group comprised 19.8% of all immigration in 2005. Canada has also created a VIP Business Immigration Program which allows immigrants with sufficient business experience or management experience to receive the Permanent Residency in a shorter period than other types of immigrations. The Province of Quebec has a program called the Immigrant Investor Program [4].

- Family class

- Under a government program, both citizens and permanent residents can sponsor family members to immigrate to Canada.

- Refugees

- Immigration of refugees and those in need of protection.

In 2010, Canada accepted 280,681 immigrants (permanent and temporary) of which 186,913 (67%) were Economic immigrants; 60,220 (22%) were Family class; 24,696 (9%) were Refugees; and 8,845 (2%) were Other.[11]

Under Canadian nationality law an immigrant can apply for citizenship after living in Canada for 1095 days (3 years) in any 4 year period provided that they lived in Canada as a permanent resident for at least two of those years.[12]

Illegal immigration in Canada

There is no credible information available on illegal immigration in Canada. Estimates of illegal immigrants range between 35,000 and 120,000.[13] James Bissett, a former head of the Canadian Immigration Service, has suggested that the lack of any credible refugee screening process, combined with a high likelihood of ignoring any deportation orders, has resulted in tens of thousands of outstanding warrants for the arrest of rejected refugee claimants, with little attempt at enforcement.[14] A 2008 report by the Auditor General Sheila Fraser stated that Canada has lost track of as many as 41,000 illegal immigrants.[15][16] This number is predicted to increase drastically with the expiration of temporary employer work permits issued in 2007 and 2008, which were not renewed in many cases because of the shortage of work due to the recession.[17]

See also

- Canada (Citizenship and Immigration) v. Khosa

- Demographics of Canada

- Emigration from the United States

- Former colonies and territories in Canada

- History of Chinese immigration to Canada

- History of immigration to Canada

- Top 25 Canadian Immigrants Award

References

- ^ a b "2006 Census: Ethnic origin, visible minorities, place of work and mode of transportation". The Daily. Statistics Canada. 2008-04-02. http://www.statcan.ca/Daily/English/080402/d080402a.htm. Retrieved 2008-10-07.

- ^ a b "Population and growth components (1851-2001 Censuses)". Statistics Canada. http://www40.statcan.ca/l01/cst01/demo03.htm?sdi=immigration. Retrieved 2010-10-18.

- ^ Hall, "Clifford Sifton: Immigration and Settlement Policy, 1896-1905."

- ^ a b Annual Immigration by Category, Citizenship and Immigration Canada. Retrieved 2 July 2006.

- ^ Canada's Immigration Program (October 2004), Library of Parliament. Retrieved 13 July 2006.

- ^ "Field Listing – Net Migration Rate"]. The World Factbook 2002. Central Intelligence Agency. http://www.umsl.edu/services/govdocs/wofact2002/fields/2112.html. Retrieved 2010-10-18.

- ^ When immigration goes awry, Toronto Star, 14 July 2006. Retrieved 5 August 2006.

- ^ Annual Immigration by Province, Citizenship and Immigration Canada. Retrieved 2 July 2006.

- ^ "Projections of the Diversity of the Canadian Population". Statistics Canada. March 9, 2010. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/cgi-bin/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&SDDS=5126&lang=en&db=imdb&adm=8&dis=2. Retrieved 2010-03-15.

- ^ "Parties prepare to battle for Immigrant votes". CTV.ca. 2010-03-14. http://www.ctv.ca/servlet/ArticleNews/story/CTVNews/20100314/Minority_Report_100314/20100314?hub=Canada. Retrieved 2010-03-15.

- ^ Citizenship & Immigration Canada: "Facts and figures 2010 – Immigration overview: Permanent and temporary residents" retrieved November 17, 2011

- ^ Citizenship & Immigration Canada retrieved November 17, 2011

- ^ "Canadians want illegal immigrants deported: poll". Ottawa Citizen (CanWest MediaWorks Publications Inc.). 20 October 2007. http://www.canada.com/nationalpost/news/story.html?id=f86690ed-a2ed-447c-8be8-21ba5a3dd922. Retrieved 2010-10-18.

- ^ "James Bissett: Stop bogus refugees before they get in". Network.nationalpost.com. http://network.nationalpost.com/np/blogs/fullcomment/archive/2007/09/27/james-bissett-stop-bogus-refugees-before-they-get-in.aspx. Retrieved 2011-01-25.

- ^ "Canada has lost track of 41,000 illegals: Fraser". CTV.ca. 2008-05-06. http://www.ctv.ca/servlet/ArticleNews/story/CTVNews/20080506/ag_report_080506/20080506?hub=TopStories. Retrieved 2011-01-25.

- ^ OAG 2008 May Report of the Auditor General of Canada[dead link]

- ^ "How we're creating an illegal workforce". Thestar.com. http://www.thestar.com/news/investigations/article/719355--how-we-re-creating-an-illegal-workforce. Retrieved 2011-01-25.

Further reading

Further information: Bibliography of Canadian demographicsHistory

- Adelman, Howard; Borowski, Allan; Burstein, Meyer; and Foster, Lois, eds. Immigration and Refugee Policy: Australia and Canada Compared (1996)

- Avery, Donald H. Reluctant Host: Canada's Response to Immigrant Workers, 1896-1994 (1996)

- Carment, David; David Jay Bercuson (2008), The world in Canada: diaspora, demography, and domestic politics, McGill-Queen's Univ. Press, ISBN 9780773532960, http://books.google.ca/books?id=OZJFUAPGh_0C&lpg=PA18&dq=Canada%20in%20World%20Affairs&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=true

- Dirks, Gerald E. Canada's Refugee Policy: Indifference or Opportunism? (1978)

- Hall, D.J. "Clifford Sifton: Immigration and Settlement Policy, 1896-1905," in Howard Palmer, ed. The Settlement of the West (1977) pp 60-85

- Hawkins, Freda. Critical Years in Immigration: Canada and Australia Compared (1990)

- Kelley, Ninette; Michael J. Trebilcock (2010), The Making of the Mosaic: A History of Canadian Immigration Policy (2nd ed.), University of Toronto Press, ISBN 9780802095367, http://books.google.ca/books?id=3IHyRvsCiKMC&lpg=PP1&dq=Immigration%20to%20Canada%E2%80%8E&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=true

- Knowles, Valerie. Strangers at Our Gates: Canadian Immigration and Immigration Policy, 1540-2006 (2008), a standard scholarly history

- Magocsi, Paul R. Encyclopedia of Canada's peoples (1999) 1334 pages; covers histy of each major group

- Powell, John (2005), Encyclopedia of North American immigration, Facts On File, ISBN 0816046581, http://books.google.ca/books?id=VNCX6UsdZYkC&lpg=PA359&dq=Immigration%20to%20Canada&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=true

- Timlin, Mabel F. "Canada's Immigration Policy, 1896-1910," Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science Vol. 26, No. 4 (Nov., 1960), pp. 517-532 in JSTOR

- Walker, Barrington (2008), The History of Immigration and Racism in Canada: Essential Readings, anadian Scholars' Press, ISBN 9781551303406, http://books.google.ca/books?id=W1YQ73A_if8C&lpg=PP1&dq=Immigration%20to%20Canada%E2%80%8E&pg=PA7#v=onepage&q&f=true

Guides

- Adu-Febiri, Francis (2009), Succeeding from the margins of Canadian society: a strategic resource for new immigrants, refugees and international students, CCB Pub ISBN 9781926585277

- Kranc,, Benjamin A; Elena Constantin (2004), Getting into Canada : how to make a successful application for permanent residence, How To Books, ISBN 1857039297, http://books.google.ca/books?id=NNyWivr-lRAC&lpg=PP1&dq=Canada&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=true

- DeRocco, John F. Chabot. (2008) From Sea to Sea to Sea: A Newcomer's Guide to Canada Full Blast Productions, ISBN 9780978473846

- Driedger, Leo; Shivalingappa S. Halli (1999), Immigrant Canada: demographic, economic, and social challenges, University of Toronto Press, ISBN 0802042767, http://books.google.ca/books?id=6WlP5yuKQfgC&lpg=PA21&dq=Canadian%20Immigration&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=true

- Moens, Alexander; Martin Collacott (2008), Immigration policy and the terrorist threat in Canada and the United States, Fraser Institute, ISBN 9780889752351, http://books.google.ca/books?id=HmiqBgnkAXYC&lpg=PA3&dq=Immigration%20to%20Canada&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=true

- Noorani, Nick; Sabrina Noorani (2008), Arrival Survival Canada: A Handbook for New Immigrants, Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780195428919, http://books.google.ca/books?id=uTw7l3NMR5oC&lpg=PA51&dq=Firearms%20in%20Canada&pg=PR1#v=onepage&q&f=true

External links

- History of Canadian immigration at Marianopolis College

- Moving Here, Staying Here: The Canadian Immigrant Experience at Library and Archives Canada

- Going to Canada - Immigration Portal: A source of free and useful information for newcomers and prospective immigrants to Canada.

- Be Aware! Canadian import laws

- Immigration Watch Canada - a non-government immigration watchdog

- Multicultural Canada website

Links related to Immigration to Canada

Links related to Immigration to Canada People of Canada

People of CanadaEthnic ancestry CanadaAfricaAmericasNorth AmericaCaribbeanEast AsiaSouth AsiaSoutheast AsiaWest AsiaEuropeNorthern EuropeWestern EuropeCentral EuropeSouthern EuropeBalkan PeninsulaEastern EuropeOceaniaAustralianDemographics Languages · Religion · Population totals · 1666 census · 1911 Census · 1996 Census · 2001 Census · 2006 Census · 2011 Census

By province & territory.. Alberta · British Columbia · Manitoba · New Brunswick · Newfoundland & Labrador · Nova Scotia · Ontario · Prince Edward Island · Quebec · Saskatchewan · Yukon · Northwest Territories · Nunavut

By city.. Edmonton · Montreal · Ottawa · Toronto · VancouverCulture

& societyArchitecture · Art · Charter · Cinema · Citizenship · Crime · Cuisine · Education · Government · Health · History · Identity · Immigration · Law

Literature · Media · Military · Multiculturalism · Music · Nationalism · Politics · Poverty · Protection of · Social welfare · Sport · Symbols · Theatrelist of

CanadiansMembers of.. Canada's Walk of Fame · Fathers of Confederation · Historic significance · Order of Canada (Companions) · The Greatest Canadian · Victoria Cross

Individuals by.. Aboriginals · Actors · Artists · Composers · Monarchs · Musicians · Painters · Prime Ministers

Net worth · Province and city · Radio personalities · Sports personalities · TV personalities · WritersOrders, medals

& decorationsImmigration to North America Sovereign states - Antigua and Barbuda

- Bahamas

- Barbados

- Belize

- Canada

- Costa Rica

- Cuba

- Dominica

- Dominican Republic

- El Salvador

- Grenada

- Guatemala

- Haiti

- Honduras

- Jamaica

- Mexico

- Nicaragua

- Panama

- Saint Kitts and Nevis

- Saint Lucia

- Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

- Trinidad and Tobago

- United States

Dependencies and

other territories- Anguilla

- Aruba

- Bermuda

- Bonaire

- British Virgin Islands

- Cayman Islands

- Curaçao

- Greenland

- Guadeloupe

- Martinique

- Montserrat

- Puerto Rico

- Saint Barthélemy

- Saint Martin

- Saint Pierre and Miquelon

- Saba

- Sint Eustatius

- Sint Maarten

- Turks and Caicos Islands

- United States Virgin Islands

Multiculturalism in Canada

Multiculturalism in CanadaAboriginal peoples in Canada Bilingualism in Canada Immigration to Canada Race and ethnicity Categories:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.