- Dover, New Hampshire

-

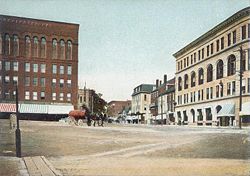

City of Dover — City — Central Square c. 1905

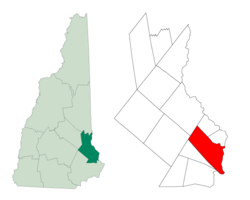

SealNickname(s): The Garrison City Location within New Hampshire Coordinates: 43°11′41″N 70°52′30″W / 43.19472°N 70.875°WCoordinates: 43°11′41″N 70°52′30″W / 43.19472°N 70.875°W Country United States State New Hampshire County Strafford Settled 1623 Incorporated 1623 (town) Incorporated 1855 (city) Government - City Manager Mike Joyal - Mayor Dean Trefethen - City Council Dennis Ciotti

Bob Carrier

Catherine Cheney

Gina Cruikshank

William Garrison

Dorothea Hooper

Jan Nedelka

Karen WestonArea - Total 29.0 sq mi (75.2 km2) - Land 26.7 sq mi (69.2 km2) - Water 2.3 sq mi (6.1 km2) 8.06% Elevation 50 ft (15 m) Population (2010) - Total 29,987 - Density 1,123.1/sq mi (433.3/km2) Time zone EST (UTC-5) - Summer (DST) EDT (UTC-4) ZIP codes 03820-03822 Area code(s) 603 FIPS code 33-18820 GNIS feature ID 0866618 Website www.ci.dover.nh.us Dover is a city in Strafford County, New Hampshire, in the United States of America. The population was 29,987 at the 2010 census,[1] the largest in the New Hampshire Seacoast region. It is the county seat of Strafford County, and home to Wentworth-Douglass Hospital, the Woodman Institute Museum, and the Children's Museum of New Hampshire.

Contents

History

Settlement

According to historian Jeremy Belknap, the area was called Wecohamet by native Abenaki Indians. The first known European to explore the region was Martin Pring from Bristol, England, in 1603. Settled in 1623 as Hilton's Point by brothers William and Edward Hilton, London fishmongers,[2] Dover is the oldest permanent settlement in New Hampshire, and the seventh oldest in the United States. It is one of the colony's four original townships, and once included Durham, Madbury, Newington and Lee. It also included Somersworth and Rollinsford, together which Indians called Newichawannock after the Newichawannock River, now known as the Salmon Falls River.

The Hiltons' name survives today at Hilton Park on Dover Point, located where they landed near the confluence of the Cochecho and Bellamy rivers with the Piscataqua. They had been sent from London by The Company of Laconia, which intended to establish a colony and fishery around the Piscataqua. In 1631, however, it contained only three houses.

In 1633, the Plantation of Cochecho was bought by a group of English Puritans who planned to settle in New England, including Viscount Saye and Sele, Baron Brooke and John Pym. They promoted colonization in America, and that year Hilton's Point was the arrival point of numerous immigrant pioneers, many from Bristol. They renamed the settlement Bristol. Atop the nearby hill, the settlers built a meeting house, surrounded by an entrenchment, to the east of which they built a jail.

Incorporation

The town was called Dover in 1637 by the new governor, Reverend George Burdett. With the arrival of Thomas Larkham in 1639, it was renamed Northam, after Northam, Devon where he had been preacher. But Lord Saye and Sele's group lost interest in their settlements, both here and at Saybrook, Connecticut, when their intention to establish a hereditary aristocracy in the colonies met with disfavor in New England. Consequently, in 1641, the plantation was sold to Massachusetts and again named Dover, possibly in honor of Robert Dover, an English lawyer who resisted Puritanism.[3]

Cochecho Massacre

Settlers felled the abundant trees to build log houses called garrisons. The town's population and business center would shift from Dover Point to Cochecho at the falls, where the river's drop of 34 feet (10 m) provided water power for industry. Indeed, Cochecho means "the rapid foaming water." Major Richard Waldron settled here and built a sawmill and gristmill.

At the end of King Philip's War, a number of aboriginal natives fleeing from the Massachusetts Bay Colony militia took refuge with the Abenaki tribe living in Dover. The Massachusetts militia ordered Waldron to attack the natives and turn the refugee combatants over to them. Waldron believed he could capture the natives without a pitched battle and so on September 7, 1676 invited the natives—about 400 in total, half local and half refugees—to participate in a mock battle against the militia. It was a trick; after the natives had fired their guns, Waldron took them prisoner. He sent both the refugee combatants and those locals who violently objected to this forced breach of hospitality to Boston, where seven or eight were convicted of insurrection and executed. The rest were sold into slavery in "foreign parts",[citation needed] mostly Barbados. The local Indians were released, but never forgave Waldron for the deception, which violated all the rules of honor and hospitality valued by the natives at that time. Richard Waldron would be appointed Chief Justice for New Hampshire in 1683.

Thirteen years passed and settlers believed the incident had been forgotten when natives began hinting that something was astir. When citizens spoke their concern to Waldron, he told them to "go and plant your pumpkins, and he would take care of the Indians."[4] On June 27, 1689, two native women appeared at each of five garrison houses, asking permission to sleep by the fire. All but one house accepted. In the dark early hours of the next day, the women unfastened the doors allowing native men who had concealed themselves to enter the town. Waldron resisted but was stunned with a hatchet then placed on his table. After dining, the Indians cut him across the belly with knives, each saying "I cross out my account." Five or six dwelling houses were burned, along with the mills. Fifty-two colonists, a full quarter of the entire population, were captured or slain.[4]

During Dummer's War, in August and September 1723, there were Indian raids on Saco, Maine and Dover, New Hampshire.[5]

Millyard

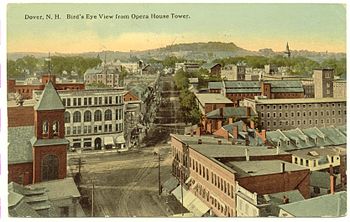

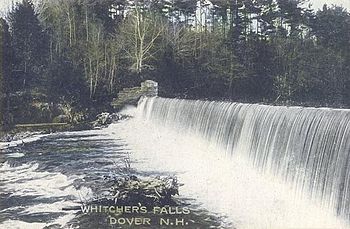

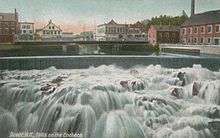

Cochecho Falls c. 1910

Cochecho Falls c. 1910

Located at the head of navigation, the falls of the Cochecho River helped bring the Industrial Revolution to 19th century Dover in a big way. The Dover Cotton Factory was incorporated in 1812, then enlarged in 1823 to become the Dover Manufacturing Company. In 1827, the Cocheco Manufacturing Company was founded (the misspelling a clerical error at incorporation), and in 1829 purchased the Dover Manufacturing Company. Expansive brick mill buildings, linked by railroad, were constructed downtown. Incorporated as a city in 1855, Dover was for a time a national leader in textiles. The mills were purchased in 1909 by the Pacific Mills of Lawrence, Massachusetts, which closed the printery in 1913 but continued spinning and weaving. During the Great Depression, however, textile mills no longer dependent on New England water power began moving to southern states in search of cheaper operating conditions, or simply went out of business. Dover's millyard shut down in 1937, and was bought at auction in 1940 by the city itself for $54,000. There were no other bids. The Cocheco Falls Millworks now has tenants including technology and government services companies, and a restaurant.[6][7]

Antique postcards

Geography and transportation

Dover is located at 43°11′28″N 70°52′43″W / 43.19111°N 70.87861°W (43.190984, -70.878533).[8]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 29.0 square miles (75 km2), of which 26.7 sq mi (69 km2) is land and 2.3 sq mi (6.0 km2) is water, comprising 8.06% of the city. Dover is drained by the Cochecho and Bellamy rivers. Long Hill, elevation 300 feet (91 m) above sea level and located 3 miles (4.8 km) northwest of the city center, is the highest point in Dover. Garrison Hill, elevation 284 ft (87 m), is a prominent hill rising directly above the center city, with a park and lookout tower on top. Dover lies fully within the Piscataqua River (Coastal) watershed.[9]

The city is crossed by New Hampshire Route 4, New Hampshire Route 9, New Hampshire Route 16, New Hampshire Route 16B, and New Hampshire Route 108. It borders the towns of Madbury to the west, Barrington to the northwest, Rochester to the north, Somersworth to the northeast, and Rollinsford to the east.

The Cooperative Alliance for Seacoast Transportation (COAST) operates a publicly funded bus network in Dover and surrounding communities in New Hampshire and Maine.[10] C&J Trailways is a private intercity bus carrier connecting Dover with other coastal New Hampshire and Massachusetts cities, including Boston.[11]

Demographics

Historical populations Census Pop. %± 1790 1,998 — 1800 2,062 3.2% 1810 2,228 8.1% 1820 2,871 28.9% 1830 5,449 89.8% 1840 6,458 18.5% 1850 8,196 26.9% 1860 8,502 3.7% 1870 9,294 9.3% 1880 11,687 25.7% 1890 12,790 9.4% 1900 13,207 3.3% 1910 13,247 0.3% 1920 13,029 −1.6% 1930 13,573 4.2% 1940 13,990 3.1% 1950 15,874 13.5% 1960 19,131 20.5% 1970 20,850 9.0% 1980 22,377 7.3% 1990 25,042 11.9% 2000 26,884 7.4% 2010 29,987 11.5% As of the census[12] of 2000, there were 26,884 people, 11,573 households, and 6,492 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,006.2 people per square mile (388.5/km²). There were 11,924 housing units at an average density of 446.3 per square mile (172.3/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 94.47% White, 1.12% African American, 0.20% Native American, 2.36% Asian, 0.06% Pacific Islander, 0.35% from other races, and 1.45% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.14% of the population.

There were 11,573 households out of which 26.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 42.5% were married couples living together, 10.3% had a female householder with no husband present, and 43.9% were non-families. 31.0% of all households were made up of individuals and 9.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.26 and the average family size was 2.87.

In the city the population was spread out with 20.8% under the age of 18, 11.2% from 18 to 24, 34.0% from 25 to 44, 20.3% from 45 to 64, and 13.7% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36 years. For every 100 females there were 92.4 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 90.6 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $43,873, and the median income for a family was $57,050. Males had a median income of $37,876 versus $27,329 for females. The per capita income for the city was $23,459. About 4.8% of families and 8.4% of the population were below the poverty line, including 9.4% of those under age 18 and 5.7% of those age 65 or over.

Education

The Dover School District consists of approximately 3600 pupils, attending Horne Street Elementary School, Garrison Elementary School, Woodman Park Elementary School, Dover Middle School and Dover High School. Dover High's athletic teams are known as The Green Wave, and the middle school's teams are The Little Green.

Saint Mary Academy, a Catholic school, has been in downtown Dover since 1912, currently serving 400 students from pre-kindergarten to 8th grade. Many students at Saint Mary's subsequently attend St. Thomas Aquinas High School, a Catholic high school located on Dover Point.

Portsmouth Christian Academy is located west of the Bellamy River in Dover, serving preschool through 12th grade.[13]

The Cocheco Arts and Technology Academy (CATA) is a public charter high school with around 100 students. It was formerly located in Barrington, New Hampshire.

Notable inhabitants

- Kenneth Appel, mathematician

- Jeremy Belknap, clergyman and historian

- Nelson Bragg, musician

- Lisa Crystal Carver, musician, performance artist and writer

- Frank Willey Clancy, politician

- Daniel Meserve Durell, congressman

- John P. Hale, U.S. senator[14]

- William Hale, congressman

- Joshua G. Hall, mayor and congressman

- John Hart, soldier

- Regan Hartley, Miss New Hampshire 2011

- Dan Christie Kingman, brigadier general

- Tommy Makem, Irish folk musician, and his sons The Makem Brothers

- Hercules Mooney, Revolutionary War officer and teacher

- Maurice J. Murphy, Jr., senator[15]

- Richard O'Kane, rear admiral[16]

- Frank M. Rines, artist

- Andrea Ross, singer and actress

- Charles H. Sawyer, manufacturer and governor of New Hampshire

- Ray Thomas, baseball player

- Jenny Thompson, swimmer and gold medalist

- John Underhill, settler and soldier

- Dike Varney, baseball player

- George H. Wadleigh, rear admiral[17]

- Major Richard Waldron, merchant, magistrate

- Richard Waldron, Jr., second President of the Province of New Hampshire

- John Wentworth, judge

- John Wentworth, Jr., lawyer

- Tappan Wentworth, congressman[18]

- Timothy R. Young, congressman

Historic sites

- First Parish Church

- Religious Society of Friends Meetinghouse

- St. Thomas Episcopal Church

- Woodman Institute

Sites of interest

- Greater Dover Chamber of Commerce & Visitor Center

- Children's Museum of New Hampshire

- Hilton Park at Dover Point

- Garrison Hill Tower

- Planet Fitness. Dover is home to the first Planet Fitness, which opened in 1992. The franchise is now nationwide.

- Woodman Institute Museum

See also

References

- Notes

- ^ United States Census Bureau, American FactFinder, 2010 Census figures. Retrieved March 23, 2011.

- ^ Stackpole, Everett Schermerhorn (1916). History of New Hampshire. New York: The American Historical Society. ISBN 9781115842945. http://books.google.com/books?id=kRn4cDDOKKMC.

- ^ Haddon 2004, pp. 64–65

- ^ a b Robinson, J. Dennis (1997). "Cochecho Massacre". Seacoast NH History. www.seacoastnh.com. http://www.seacoastnh.com/history/colonial/massacre.html. Retrieved 2010-07-06.

- ^ (William Williamson, p. 123)

- ^ "Cocheco Falls Millworks". Cocheco Falls Millworks. http://www.dovermills.com/index.htm. Retrieved August 15, 2011.

- ^ Beaudoin, Cathleen. "A Yarn to Follow: The Dover Cotton Factory 1812—1821". Dover Public Library. http://www.dover.lib.nh.us/DoverHistory/mill_history%20new.htm. Retrieved August 15, 2011.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. http://www.census.gov/geo/www/gazetteer/gazette.html. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ^ Foster, Debra H.; Batorfalvy, Tatianna N.; and Medalie, Laura (1995). Water Use in New Hampshire: An Activities Guide for Teachers. U.S. Department of the Interior and U.S. Geological Survey. http://nh.water.usgs.gov/Publications/nh.intro.html.

- ^ "Take a closer look at COAST". www.coastbus.org. http://www.coastbus.org/. Retrieved 2010-07-06.

- ^ "C&J: Connecting Dover, Durham, Portsmouth and Newburyport to Boston South Station and Logan Airport". www.ridecj.com. http://www.ridecj.com/. Retrieved 2010-07-06.

- ^ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. http://factfinder.census.gov. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ^ "Portsmouth Christian Academy - In the News". www.pcaschool.org. http://www.pcaschool.org/. Retrieved 2010-07-06.

- ^ "Hale, John Parker". Biographical Guide to the U. S. Congress. bioguide.congress.gov. http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=H000034. Retrieved 2010-07-06.

- ^ "Murphy, Maurice J., Jr.". Biographical Guide to the U. S. Congress. bioguide.congress.gov. http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=M001100. Retrieved 2010-07-06.

- ^ "Rear Admiral Richard H. O'Kane, U.S. Navy". University of New Hampshire. http://www.unh.edu/army/alumni/okane.html. Retrieved 2010-07-06.

- ^ "Wadleigh, George H., Rear Admiral, USN". Naval Historical Center. www.history.navy.mil. http://www.history.navy.mil/photos/pers-us/uspers-w/g-wdlgh.htm. Retrieved 2010-07-06.

- ^ "Wentworth, Tappan". Biographical Guide to the U. S. Congress. bioguide.congress.gov. http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=W000297. Retrieved 2010-07-06.

- Bibliography

- Haddon, Celia (2004), The First Ever English Olimpick Games, Hodder & Stoughton, ISBN 0-340-86274-2

External links

- City website

- Dover Public Library

- The Many Names of Dover

- Sketch of Dover, New Hampshire

- New Hampshire Economic and Labor Market Information Bureau Profile

- Dover Chamber of Commerce

- Dover Main Street Community

- Dover Was First

Municipalities and communities of Strafford County, New Hampshire County seat: Dover Cities Dover | Rochester | Somersworth

Towns Barrington | Durham | Farmington | Lee | Madbury | Middleton | Milton | New Durham | Rollinsford | Strafford

Villages Bow Lake Village | Center Strafford | East Rochester | Milton Mills

Categories:- Dover, New Hampshire

- Cities in New Hampshire

- Populated places in Strafford County, New Hampshire

- County seats in New Hampshire

- Early American industrial centers

- Populated places established in 1623

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.