- Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura

-

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura Classification and external resources

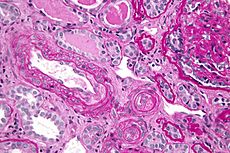

Micrograph showing an advanced thrombotic microangiopathy, as may be seen in TTP. Kidney biopsy. PAS stain.ICD-10 M31.1 (ILDS M31.110) ICD-9 446.6 OMIM 274150 DiseasesDB 13052 MedlinePlus 000552 eMedicine emerg/579 neuro/499 med/2265 MeSH D011697 Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP or Moschcowitz syndrome[1]:822) is a rare disorder of the blood-coagulation system, causing extensive microscopic thromboses to form in small blood vessels throughout the body (thrombotic microangiopathy).[2][3] Most cases of TTP arise from inhibition of the enzyme ADAMTS13, a metalloprotease responsible for cleaving large multimers of von Willebrand factor (vWF) into smaller units. A rarer form of TTP, called Upshaw-Schülman syndrome, is genetically inherited as a dysfunction of ADAMTS13. If large vWF multimers persist there is tendency for increased coagulation.[4]

Red blood cells passing the microscopic clots are subjected to shear stress which damages their membranes, leading to intravascular hemolysis and schistocyte formation. Reduced blood flow due to thrombosis and cellular injury results in end organ damage. Current therapy is based on support and plasmapheresis to reduce circulating antibodies against ADAMTS13 and replenish blood levels of the enzyme.[4]

Contents

Signs and symptoms

Classically, the following five features ("pentad") are indicative of TTP;[5] in most cases, some of these are absent.[3]

- Neurologic symptoms (fluctuating), such as hallucinations, bizarre behavior, altered mental status, stroke or headaches

- Kidney failure

- Fever

- Thrombocytopenia (low platelet count), leading to bruising or purpura

- Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (anemia, jaundice and a blood film featuring evidence of mechanical fragmentation of red blood cells)

Due to the high mortality of untreated TTP, a presumptive diagnosis of TTP is made even when only microangiopathic hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia is seen, and therapy is started.

The symptoms of TTP may at first be subtle - starting with malaise, fever, headache and sometimes diarrhea. As the condition progresses clots (thrombi) form within blood vessels and platelets (clotting cells) are consumed. Bruising, and rarely bleeding, results and may be spontaneous. The bruising often takes the form of purpura while the most common site of bleeding, if it occurs, is from the nose or gums. Larger bruises (ecchymoses) may also develop.

Clots formed within the circulation can temporarily disrupt local blood supply. TTP preferentially affects the blood vessels of the brain and kidneys. Thus a patient may experience headache, confusion, difficulty speaking, transient paralysis, numbness or even fits whilst high blood pressure (hypertension) may be found on examination.[6]

Platelet associated IgG & complement levels are usually normal in TTP.

Causes and pathogenesis

TTP, as with other microangiopathic hemolytic anemias (MAHAs), is caused by spontaneous aggregation of platelets and activation of coagulation in the small blood vessels. Platelets are consumed in the coagulation process, and bind fibrin, the end product of the coagulation pathway. These platelet-fibrin complexes form microthrombi which circulate in the vasculature and cause shearing of red blood cells, resulting in hemolysis.[3]

Roughly, there are two forms of TTP: idiopathic and secondary TTP. A special case is the inherited deficiency of ADAMTS13, known as the Upshaw-Schülman syndrome.[3]

Idiopathic TTP

The idiopathic form of TTP was recently linked to the inhibition of the enzyme ADAMTS13 by antibodies, rendering TTP an autoimmune disease. ADAMTS13 is a metalloproteinase responsible for the breakdown of von Willebrand factor (vWF), a protein that links platelets, blood clots, and the blood vessel wall in the process of blood coagulation. Very large vWF multimers are more prone to lead to coagulation. Hence, without proper cleavage of vWF by ADAMTS13, coagulation occurs at a higher rate, especially in the part of the blood vessel system where vWF is most active due to high shear stress: in the microvasculature.[4]

In idiopathic TTP, severely decreased (<5% of normal) ADAMTS13 activity can be detected in most (80%) patients, and inhibitors are often found in this subgroup (44-56%). The relationship of reduced ADAMTS13 to the pathogenesis of TTP is known as the Furlan-Tsai hypothesis, after the two independent groups of researchers who published their research in the same issue of the New England Journal of Medicine in 1998.[7][8][9] This theory is seen as insufficient to explain the etiology of TTP, since many patients with hereditary lack of ADAMTS13 activity do not manifest clinical symptoms of TTP.[citation needed]

Secondary TTP

Secondary TTP is diagnosed when the patient's history mentions one of the known features associated with TTP. It comprises about 40% of all cases of TTP. Predisposing factors are:[3]

- Cancer

- Bone marrow transplantation

- Pregnancy

- Medication use:

- Quinine

- Platelet aggregation inhibitors (ticlopidine and clopidogrel)

- Immunosuppressants (cyclosporine, mitomycin, tacrolimus/FK506, interferon-α)

- HIV-1 infection

The mechanism of secondary TTP is poorly understood, as ADAMTS13 activity is generally not as depressed as in idiopathic TTP, and inihibitors cannot be detected. Probable etiology may involve, at least in some cases, endothelial damage.[citation needed]

Upshaw-Schülman syndrome

A hereditary form of TTP is called the Upshaw-Schülman syndrome; this is generally due to inherited deficiency of ADAMTS13 (frameshift and point mutations).[10][11][12] Patients with this inherited ADAMTS13 deficiency have a surprisingly mild phenotype, but develop TTP in clinical situations with increased von Willebrand factor levels, e.g. infection. Reportedly, 5-10% of all TTP cases are due to Upshaw-Schülman syndrome.[citation needed]

Condition Prothrombin time Partial thromboplastin time Bleeding time Platelet count Vitamin K deficiency or warfarin prolonged normal or mildly prolonged unaffected unaffected Disseminated intravascular coagulation prolonged prolonged prolonged decreased von Willebrand disease unaffected prolonged prolonged unaffected Hemophilia unaffected prolonged unaffected unaffected Aspirin unaffected unaffected prolonged unaffected Thrombocytopenia unaffected unaffected prolonged decreased Liver failure, early prolonged unaffected unaffected unaffected Liver failure, end-stage prolonged prolonged prolonged decreased Uremia unaffected unaffected prolonged unaffected Congenital afibrinogenemia prolonged prolonged prolonged unaffected Factor V deficiency prolonged prolonged unaffected unaffected Factor X deficiency as seen in amyloid purpura prolonged prolonged unaffected unaffected Glanzmann's thrombasthenia unaffected unaffected prolonged unaffected Bernard-Soulier syndrome unaffected unaffected prolonged decreased or unaffected Treatment

Since the early 1990s, plasmapheresis has become the treatment of choice for TTP.[13] This is an exchange transfusion involving removal of the patient's blood plasma through apheresis and replacement with donor plasma (fresh frozen plasma or cryosupernatant); the procedure has to be repeated daily to eliminate the inhibitor and abate the symptoms. If pheresis is not available, fresh frozen plasma can be infused, but the volume able to be given safely is limited due to the danger of fluid overload. Lactate dehydrogenase levels are generally used to monitor disease activity. Plasmapheresis may need to be continued for 1–8 weeks before patients with idiopathic TTP cease to consume platelets and begin to normalize their hemoglobin. No single laboratory test (platelet count, LDH, ADAMTS13 level, or inhibitory factor) is indicative of recovery; research protocols have used improvement or normalization of LDH as a measure for ending plasmapheresis. Although patients may be critically ill with failure of multiple organ systems during the acute illness, including renal failure, myocardial ischemia, and neurologic symptoms, recovery over several months may be complete in the absence of a frank myocardial infarct, stroke, or CNS hemorrhage.[citation needed]

Most patients with refractory or relapsing TTP receive additional immunosuppressive therapy, with glucocorticoid steroids (e.g. prednisolone or prednisone), vincristine, cyclophosphamide, splenectomy, rituximab or a combination of the above.

Children with Upshaw-Schulman syndrome receive prophylactic plasma every two to three weeks; this maintains adequate levels of functioning ADAMTS13.

Measurements of LDH, platelets and schistocytes are used to monitor disease progression or remission.

Epidemiology

The incidence of TTP is about 4-6 per million people per year.[14] Idiopathic TTP occurs more often in women and black/African-American people, while the secondary forms do not show this distribution.[citation needed] Pregnant women and women in the postpartum period accounted for a notable portion (12-31%) of the cases in some studies; TTP affects approximately 1 in 25,000 pregnancies.[15]

Prognosis

The mortality rate is approximately 95% for untreated cases, but the prognosis is reasonably favorable (80-90% survival) for patients with idiopathic TTP diagnosed and treated early with plasmapheresis.[16]

History

TTP was initially described by Dr Eli Moschcowitz at the Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City in 1925. Moschcowitz ascribed the disease (incorrectly, as now known) to a toxic cause. Moschcowitz noted that his patient, a 16 year-old girl, had anemia, petechiae (purpura), microscopic hematuria, and, at autopsy, disseminated microvascular thrombi.[17] In 1966, a review of 16 new cases and 255 previously reported ones led to the formulation of the classical pentad of symptoms and findings; in this series, mortality rates were found to be very high (90%).[5] While response to blood transfusion had been noted before, a 1978 report and subsequent studies showed that blood plasma was highly effective in improving the disease process.[14] In 1991 it was reported that plasma exchange provided better response rates compared to plasma infusion.[18] In 1982 the disease had been linked with abnormally large von Willebrand factor multimers, and the late 1990s saw the identification of a deficient protease in people with TTP. ADAMTS13 was identified on a molecular level in 2001.[14]

References

- ^ James, William D.; Berger, Timothy G. (2006). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: clinical Dermatology. Saunders Elsevier. ISBN 0-7216-2921-0.

- ^ "thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ^ a b c d e Moake JL (2002). "Thrombotic microangiopathies". N. Engl. J. Med. 347 (8): 589–600. doi:10.1056/NEJMra020528. PMID 12192020.

- ^ a b c Moake JL (2004). "von Willebrand factor, ADAMTS-13, and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura". Semin. Hematol. 41 (1): 4–14. doi:10.1053/j.seminhematol.2003.10.003. PMID 14727254.

- ^ a b Amorosi EL, Ultmann JE (1966). "Thrombocytopic purpura: report of 16 cases and review of the literature". Medicine (Baltimore) 45: 139–159.

- ^ http://www.netdoctor.co.uk/diseases/facts/ttp.htm

- ^ Moake JL (1998). "Moschcowitz, multimers, and metalloprotease". N. Engl. J. Med. 339 (22): 1629–31. doi:10.1056/NEJM199811263392210. PMID 9828253.

- ^ Furlan M, Robles R, Galbusera M et al. (1998). "von Willebrand factor-cleaving protease in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and the hemolytic-uremic syndrome". N. Engl. J. Med. 339 (22): 1578–84. doi:10.1056/NEJM199811263392202. PMID 9828245.

- ^ Tsai HM, Lian EC (1998). "ANTIBODIES TO VON WILLEBRAND FACTOR–CLEAVING PROTEASE IN ACUTE THROMBOTIC THROMBOCYTOPENIC PURPURA". N. Engl. J. Med. 339 (22): 1585–94. doi:10.1056/NEJM199811263392203. PMC 3159001. PMID 9828246. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3159001.

- ^ Schulman I, Pierce M, Lukens A, Currimbhoy Z (July 1960). "Studies on thrombopoiesis. I. A factor in normal human plasma required for platelet production; chronic thrombocytopenia due to its deficiency" (PDF). Blood 16 (1): 943–57. PMID 14443744. http://bloodjournal.hematologylibrary.org/cgi/reprint/16/1/943.

- ^ Upshaw JD (June 1978). "Congenital deficiency of a factor in normal plasma that reverses microangiopathic hemolysis and thrombocytopenia". N. Engl. J. Med. 298 (24): 1350–2. doi:10.1056/NEJM197806152982407. PMID 651994.

- ^ Levy GG, Nichols WC, Lian EC et al. (October 2001). "Mutations in a member of the ADAMTS gene family cause thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura". Nature 413 (6855): 488–94. doi:10.1038/35097008. PMID 11586351.

- ^ Zheng XL, Kaufman RM, Goodnough LT, Sadler JE (2004). "Effect of plasma exchange on plasma ADAMTS13 metalloprotease activity, inhibitor level, and clinical outcome in patients with idiopathic and nonidiopathic thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura". Blood 103 (11): 4043–9. doi:10.1182/blood-2003-11-4035. PMID 14982878.

- ^ a b c Sadler JE (July 2008). "Von Willebrand factor, ADAMTS13, and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura". Blood 112 (1): 11–8. doi:10.1182/blood-2008-02-078170. PMC 2435681. PMID 18574040. http://bloodjournal.hematologylibrary.org/cgi/content/full/112/1/11.

- ^ X. Long Zheng; J. Evan Sadler (2008). "Pathogenesis of Thrombotic Microangiopathies". Annual Review of Pathology (Annual Reviews) 3: 249–277. doi:10.1146/annurev.pathmechdis.3.121806.154311. PMC 2582586. PMID 18215115. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2582586.

- ^ Tsai, Han-Mou (February 2006). "Current Concepts in Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura". Annual Review of Medicine (Annual Reviews) 57: 419–436. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.57.061804.084505. PMC 2426955. PMID 16409158. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2426955.

- ^ Moschcowitz E (1924). "An acute febrile pleiochromic anemia with hyaline thrombosis of the terminal arterioles and capillaries: an undescribed disease". Proc NY Pathol Soc 24: 21–4. Reprinted in Mt Sinai J Med 2003;70(5):322-5, PMID 14631522.

- ^ Rock GA, Shumak KH, Buskard NA et al. (August 1991). "Comparison of plasma exchange with plasma infusion in the treatment of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Canadian Apheresis Study Group". N. Engl. J. Med. 325 (6): 393–7. doi:10.1056/NEJM199108083250604. PMID 2062330.

External links

- Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura from MedlinePlus

- What is TTP? from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

- Platelets on the Web from University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center

- TTP in the Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy

Pathology: hematology · hematologic diseases of RBCs and megakaryocytes / MEP (D50-69,74, 280-287) Red

blood cells↑↓enzymopathy: G6PD · glycolysis (PK, TI, HK)

hemoglobinopathy: Thalassemia (alpha, beta, delta) · Sickle-cell disease/trait · HPFH

membrane: Hereditary spherocytosis (Minkowski-Chauffard syndrome) · Hereditary elliptocytosis (Southeast Asian ovalocytosis) · Hereditary stomatocytosisAcquiredHereditary: Fanconi anemia · Diamond–Blackfan anemia

Acquired: PRCA · Sideroblastic anemia · MyelophthisicOtherCoagulation/

coagulopathy↑primary: Antithrombin III deficiency · Protein C deficiency/Activated protein C resistance/Protein S deficiency/Factor V Leiden · Hyperprothrombinemia

acquired:Thrombocytosis (essential) · DIC (Congenital afibrinogenemia, Purpura fulminans) · autoimmune (Antiphospholipid)↓adhesion (Bernard–Soulier syndrome) · aggregation (Glanzmann's thrombasthenia) · platelet storage pool deficiency (Hermansky–Pudlak syndrome, Gray platelet syndrome)Clotting factorCategories:- Coagulopathies

- Autoimmune diseases

- Rare diseases

- Vascular-related cutaneous conditions

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.