- Antiphospholipid syndrome

-

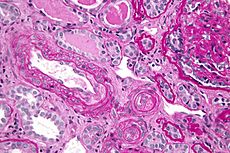

Antiphospholipid syndrome Classification and external resources

Micrograph showing an advanced thrombotic microangiopathy, as may be seen in ALPA syndrome. Kidney biopsy. PAS stain.ICD-10 D68.8 (ILDS D68.810) ICD-9 ICD9 289.81 OMIM 107320 DiseasesDB 775 eMedicine med/2923 MeSH D016736 Antiphospholipid syndrome or antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APS or APLS or), often also Hughes syndrome, is an autoimmune, hypercoagulable state caused by antibodies against cell-membrane phospholipids that provokes blood clots (thrombosis) in both arteries and veins as well as pregnancy-related complications such as miscarriage, stillbirth, preterm delivery, or severe preeclampsia. The syndrome occurs due to the autoimmune production of antibodies against phospholipid (aPL), a cell membrane substance. In particular, the disease is characterised by antibodies against cardiolipin (anti-cardiolipin antibodies) and β2 glycoprotein I. The term "primary antiphospholipid syndrome" is used when APS occurs in the absence of any other related disease. APS however also occurs in the context of other autoimmune diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), in which case the term "secondary antiphospholipid syndrome" is used. In rare cases, APS leads to rapid organ failure due to generalised thrombosis; this is termed "catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome" (CAPS) and is associated with a high risk of death.

Antiphospholipid syndrome is diagnosed with blood tests. It often requires treatment with anticoagulant medication such as warfarin or heparin to reduce the risk of further episodes of thrombosis and improve the prognosis of pregnancy.

Contents

Signs and symptoms

The presence of antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL) in the absence of blood clots or pregnancy-related complications does not indicate APS (see below for the diagnosis of APS).

Antiphospholipid syndrome can cause (arterial/venous) blood clots (in any organ system) or pregnancy-related complications. In APS patients, the most common venous event is deep vein thrombosis of the lower extremities (blood clot of the deep veins of the legs) and the most common arterial event is stroke. In pregnant women affected by APS, miscarriage can occur prior to 20 week of gestation, while pre-eclampsia is reported to occur after that time. Placental infarctions, early deliveries and stillbirth are also reported in women with APS. In some cases, APS seems to be the leading cause of mental and/or development retardation in the newborn, due to an aPL-induced inhibition of trophoblast differentiation. The antiphospholipid syndrome responsible for most of the miscarriages in later trimesters seen in concomitant systemic lupus erythematosus and pregnancy.[1]

Other common findings, although not part of the APS classification criteria, are thrombocytopenia (low platelet count), heart valve disease, and livedo reticularis (a skin condition). Some patients report headaches, migraines, and oscillopsia.[2]

Very few patients with primary APS go on to develop SLE.

Risk factors

Risk factors for developing antiphospholipid syndrome include:[citation needed]

- Primary APS

- Secondary APS

Mechanism

Antiphospholipid syndrome is an autoimmune disease, in which "antiphospholipid antibodies" (anticardiolipin antibodies and lupus anticoagulant) react against proteins that bind to anionic phospholipids on plasma membranes. Like many autoimmune diseases, it is more common in women than in men. The exact cause is not known, but activation of the system of coagulation is evident. Clinically important antiphospholipid antibodies (those that arise as a result of the autoimmune process) are associated with thrombosis and vascular disease. The syndrome can be divided into primary (no underlying disease state) and secondary (in association with an underlying disease state) forms.

Anti-ApoH and a subset of anti-cardiolipin antibodies bind to ApoH, which in turn inhibits Protein C, a glycoprotein with regulatory function upon the common pathway of coagulation (by degradating activated factor V).

LAC antibodies bind to prothrombin, thus increasing its cleavage to thrombin, its active form.

In APS there are also antibodies binding to: Protein S, which is a co-factor of protein C. Thus, anti-protein S antibodies decrease protein C efficiency;

Annexin A5, which forms a shield around negatively-charged phospholipid molecules, thus reducing their availability for coagulation. Thus, anti-annexin A5 antibodies increase phospholipid-dependent coagulation steps.

The Lupus anticoagulant antibodies are those that show the closest association with thrombosis, those that target β2glycoprotein 1 have a greater association with thrombosis than those that target prothrombin. Anticardiolipin antibodies are associated with thrombosis at moderate to high titres (>40 GPLU or MPLU). Patients with both Lupus anticoagulant antibodies and moderate/high titre anticardiolipin antibodies show a greater risk of thrombosis than with one alone.

Diagnosis

Antiphospholipid syndrome is tested for in the laboratory using both liquid phase coagulation assays (lupus anticoagulant) and solid phase ELISA assays (anti-cardiolipin antibodies).

Genetic thrombophilia is part of the differential diagnosis of APS and can coexist in some APS patients. Presence of genetic thrombophilia may determine the need for anticoagulation therapy. Thus genetic thrombophilia screening can consist of:

- Further studies for Factor V Leiden variant and the prothrombin mutation, Factor VIII levels, MTHFR mutation.

- Levels of protein C, free and total protein S, Factor VIII, antithrombin, plasminogen, tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1)

The testing of antibodies to the possible individual targets of aPL such as β2 glycoprotein 1 and antiphosphatidyl serine is currently under debate as testing for anticardiolipin appears to be currently sensitive and specific for diagnosis of APS even though cardiolipin is not considered an in vivo target for antiphospholipid antibodies.

Lupus anticoagulant

This is tested for by using a minimum of two coagulation tests that are phospholipid sensitive, due to the heterogeneous nature of the lupus anticoagulant antibodies. The patient on initial screening will typically have been found to have a prolonged APTT that does not correct in an 80:20 mixture with normal human plasma (50:50 mixes with normal plasma are insensitive to all but the highest antibody levels). The APTT (plus 80:20 mix), dilute Russell's viper venom time (DRVVT), the kaolin clotting time (KCT), dilute thromboplastin time (TDT/DTT) or prothrombin time (using a lupus sensitive thromboplastin) are the principal tests used for the detection of lupus anticoagulant. These tests must be carried out on a minimum of two occasions at least 6 weeks apart and be positive on each occasion demonstrating persistent positivity to allow a diagnosis of antiphospholipid syndrome. This is to prevent patients with transient positive tests (due to infection etc.) being diagnosed as positive.

Distinguishing a lupus antibody from a specific coagulation factor inhibitor (e.g.: Factor VIII). This is normally achieved by differentiating the effects of a lupus anticoagulant on factor assays from the effects of a specific coagulation factor antibody. The lupus anticoagulant will inhibit all the contact activation pathway factors (Factor VIII, Factor IX, Factor XI and Factor XII). Lupus anticoagulant will also rarely cause a factor assay to give a result lower than 35 iu/dl (35%) where as a specific factor antibody will rarely give a result higher than 10 iu/dl (10%). Monitoring IV anticoagulant therapy by the APTT ratio is compromised due to the effects of the lupus anticoagulant and in these situations is generally best performed using a chromogenic assay based on the inhibition of Factor Xa by antithrombin in the presence of heparin.

Anticardiolipin antibodies

These can be detected using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) immunological test, which screens for the presence of β2glycoprotein 1 dependent anticardiolipin antibodies (ACA).

A Low platelet count and positivity for antibodies against β2-glycoprotein 1 or phosphatidylserine may also be observed in a positive diagnosis.

Criteria

Classification with APS requires evidence of both one or more specific, documented clinical events (either a vascular thrombosis and/or adverse obstetric event) and the confirmed presence of a repeated aPL. The Sapporo APS classification criteria (1998, published in 1999) were replaced by the Sydney criteria in 2006. [3] Based on the most recent criteria, classification with APS requires one clinical and one laboratory manifestation:

- Clinical:

- A documented episode of arterial, venous, or small vessel thrombosis—other than superficial venous thrombosis in any tissue or organ by objective validated criteria with no significant evidence of inflammation in the vessel wall and/or

- 1 or more unexplained deaths of a morphologically normal fetus (documented by ultrasound or direct examination of the fetus) at or beyond the 10th week of gestation and/or 3 or more unexplained consecutive spontaneous abortions before the 10th week of gestation, with maternal anatomic or hormonal abnormalities and paternal and maternal chromosomal causes excluded or at least 1 premature birth of a morphologically normal neonate before the 34th week of gestation due to eclampsia or severe pre-eclampsia according to standard definitions, or recognized features of placental insufficiency plus

- Laboratory:

- Anti-cardiolipin IgG and/or IgM measured by standardized, non-cofactor dependent ELISA on 2 or more occasions, not less than 12 weeks apart; medium or high titre (i.e., > 40 GPL or MPL, or > the 99th percentile) and/or

- Anti-β2 glycoprotein I IgG and/or IgM measured by standardized ELISA on 2 or more occasions, not less than 12 weeks apart; medium or high titre (> the 99th percentile) and/or

- Lupus anticoagulant detected on 2 occasions not less than 12 weeks apart according to the guidelines of the International Society of Thrombosis and Hemostasis.

There are 3 distinct APS disease entities: primary (the absence of any comorbidity), secondary (when there is a pre-existing autoimmune condition, most frequently systemic lupus erythematosus, SLE), and catastrophic (when there is simultaneous multi-organ failure with small vessel occlusion).

The International Consensus Statement is commonly used for Catastrophic APS diagnosis.[4] Based on this statement, Definite CAPS diagnosis requires:

- a) Vascular thrombosis in three or more organs or tissues and

- b) Development of manifestations simultaneously or in less than a week 'and

- c) Evidence of small vessel thrombosis in at least one organ or tissue and

- d) Laboratory confirmation of the presence of aPL.

Some serological tests for syphilis may be positive in aPL-positive patients (aPL bind to the lipids in the test and make it come out positive) although the more specific tests for syphilis that use recombinant antigens will be negative.

Treatment

Often, this disease is treated by giving aspirin to inhibit platelet activation, and/or warfarin as an anticoagulant. The goal of the prophylactic treatment is to maintain the patient's INR between 2.0 - 3.0.[5] It is not usually done in patients who have not had any thrombotic symptoms. During pregnancy, low molecular weight heparin and low-dose aspirin are used instead of warfarin because of warfarin's teratogenicity. Women with recurrent miscarriage are often advised to take aspirin and to start low molecular weight heparin treatment after missing a menstrual cycle. In refractory cases plasmapheresis may be used.[citation needed]

Prognosis

The long-term prognosis for APS is determined mainly by recurrent thrombosis, which may occur in up to 29% of patients, sometimes despite antithrombotic therapy.[citation needed]

History

Antiphospholipid syndrome was described in full in the 1980s, after various previous reports of specific antibodies in people with systemic lupus erythematosus and thrombosis.[6][7] The syndrome is sometimes referred to as "Hughes syndrome", after the rheumatologist Dr. Graham R.V. Hughes (St. Thomas' Hospital, London, UK) who worked at the Louise Coote Lupus Unit at St Thomas' Hospital in London and played a central role in the description of the condition.[8][7]

References

- ^ Lupus and Pregnancy by Michelle Petri. The Johns Hopkins Lupus Center. Retrieved May 2011

- ^ Rinne T, Bronstein AM, Rudge P, Gresty MA, Luxon LM (1998). "Bilateral loss of vestibular function: clinical findings in 53 patients". J. Neurol. 245 (6–7): 314–21. doi:10.1007/s004150050225. PMID 9669481.

- ^ Miyakis S, Lockshin MD, Atsumi T et al. (February 2006). "International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS)". J. Thromb. Haemost. 4 (2): 295–306. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01753.x. PMID 16420554.

- ^ Asherson RA, Cervera R, de Groot PG et al. (2003). "Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome: international consensus statement on classification criteria and treatment guidelines". Lupus 12 (7): 530–4. doi:10.1191/0961203303lu394oa. PMID 12892393.

- ^ Horton JD, Bushwick BM (1999). "Warfarin therapy: evolving strategies in anticoagulation". American Family Physician 59 (3): 635–46. PMID 10029789.

- ^ Ruiz-Irastorza G, Crowther M, Branch W, Khamashta MA (October 2010). "Antiphospholipid syndrome". Lancet 376 (9751): 1498–509. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60709-X. PMID 20822807.

- ^ a b Hughes GR (October 1983). "Thrombosis, abortion, cerebral disease, and the lupus anticoagulant". Br. Med. J. (Clin Res Ed) 287 (6399): 1088–9. doi:10.1136/bmj.287.6399.1088. PMC 1549319. PMID 6414579. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1549319.

- ^ Sanna G, D'Cruz D, Cuadrado MJ (August 2006). "Cerebral manifestations in the antiphospholipid (Hughes) syndrome". Rheum. Dis. Clin. North Am. 32 (3): 465–90. doi:10.1016/j.rdc.2006.05.010. PMID 16880079.

Bibliography

- Triona Holden (2003). Positive Options for Antiphospholipid Syndrome (APS): Self-Help and Treatment. Hunter House (CA). ISBN 0-89793-409-1.

- Kay Thackray (2003). Sticky Blood Explained. Braiswick. ISBN 1-898030-77-4. A personal account of dealing with the condition.

- Graham R V Hughes (2009). Understanding Hughes Syndrome: Case Studies for Patients. Springer. ISBN 1-848003-75-7. 50 case studies to help you work out whether you have it.

External links

- APS Foundation of America, Inc.

- Hughes Syndrome Foundation

- Interview with Hughes The Daily Telegraph February 2, 2009. Accessed February 3, 2009.

House Md, 6:4 Instant karma

Anti-nuclear antibody PBC: Anti-gp210 · Anti-p62 · Anti-sp100

ENA: Anti-topoisomerase/Scl-70 · Anti-Jo1 · ENA4 (Anti-Sm, Anti-nRNP, Anti-Ro, Anti-La)

Anti-dsDNAAnti-mitochondrial antibody Anti-cytoplasm antibody Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic (C-ANCA, P-ANCA) · Anti-smooth muscle (Anti-actin) · Anti-TPO/AntimicrosomalCell membrane Extracellular Multiple locations Anti-phospholipid · Anti-apolipoproteinUngrouped Categories:- Coagulopathies

- Rheumatology

- Autoimmune diseases

- Neurological disorders

- Obstetrics

- Syndromes

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.